Contemporary scholars of feminism have significantly advanced our understanding of the movement's multiracial history.Footnote 1 Yet the global origins of the New Woman—a towering feminist figure typically associated with late-Victorian authors and heroines who pursued education, careers, and suffrage—remain obscure. In particular, the rise of this controversial figure in nineteenth-century India has received inadequate attention, distorting our view of the wider movement. Tracing the sprawling networks of transimperial circulation can help paint a more comprehensive picture of who the New Women were and how they shaped modern feminism.

Specialists in nineteenth-century Indian literature know well that empowered, self-fashioning heroines emerged as protagonists in early women's writing from across the subcontinent. Yet as Susmita Roye has recently observed, “the roots of Indian women's fiction in English are still gravely understudied” (1). This is particularly true of the novels, autobiographies, poems, and social critiques that emerged in the century's final decades, arising alongside Anglo-American New Womanhood but also partly anticipating it. The wider discipline has yet to recognize the significance of these works and the challenge they pose to familiar conceptions of the genre. From 1970s rediscoveries of the New WomanFootnote 2 to contemporary reassessments,Footnote 3 mainstream scholarship remains dominated by Western texts, even when focused on empire.Footnote 4 Though Ann Heilmann notes that recent critics have “scrutinized the racialist and imperialist roots of New Woman thought” and relinquished “an exclusive concentration on white Anglo-American New Women” (“New Woman” 32), this shift remains far from complete, despite rich research by scholars like Roye, Barnita Bagchi, Priya Joshi, Susie Tharu and K. Lalita, Chandani Lokugé, and Geraldine Forbes.Footnote 5

These omissions ironically narrow the canon bequeathed by the nineteenth century. Anglo-American cultural arbiters of the age—from early canonizers like Edmund Gosse and Edmund Clarence Stedman to early feminists like Mary Frances Billington and Elizabeth L. Grigg—recognized Indian writers as New Women and absorbed them into an emergent English canon. Far from concurring that their works should be annexed as jewels in the crown of British culture, this essay argues that they emblematize a wider phenomenon in which major fin de siècle genres did not just gain transimperial purchase through expanding colonial markets but were born as transimperial genres. A significant global incarnation of New Womanhood was created by “self-representing” Indian women—such as Toru Dutt, Krupa Satthianadhan, Shèvantibāi Nikambé, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, Pandita Ramabai, and Cornelia Sorabji—who engaged in endogenous and exogenous feminist debates around polarizing issues like female education, purdah (female seclusion), child marriage, and satiFootnote 6 (Sarkar, “Many Faces” 29). While their treatments were diverse, these authors shared key commonalities: all lived primarily in India, all wrote regularly in English, all were unusually well educated, and most were high-caste converts to Christianity. Because some preceded or reciprocally influenced more familiar authors, studying them helps expand not only the canon but also dated generic criteria. This in turn may help combat the “canonical inertia” that occurs when long-obscured texts are identified by scholars but left out of the anthologies and syllabi that define the field that students encounter.Footnote 7

The British arrogation of Indian authors began with Dutt's untimely death in 1877 at the age of twenty-one. In The Calcutta Review, the demise of the multilingual Bengali polymath was mourned as a loss to British culture: “She wrote in English with all the delicacy and all the good taste of a highly cultivated Englishwoman,” attested the editor, and her work “promised to obtain for her an honoured place among the English poets of the present day” (“Poetry” 421). When Stedman launched his canonizing Victorian Anthology (1895), he included Dutt among the “recent poets of Great Britain” (545). In 1921, H. A. L. Fisher agreed that Dutt “has by sheer force of native genius earned for herself the right to be enrolled in the great fellowship of English poets” (vii), echoing Gosse's foundational 1881 proclamation: “When the history of the literature of our country comes to be written, there is sure to be a page in it dedicated to this fragile exotic blossom of song” (xxvii). Dutt's induction into the British canon was devised at least partly to combat rival claims from nineteenth-century French orientalists like Clarisse Bader, Garcin de Tassy, and James Darmesteter, who deemed her “Hindoue de race et de tradition, Anglaise d’éducation, Française du coeur” (“Hindu by race and tradition, English by education, French at heart”; Darmesteter 269; my trans.). These appeals inspired an 1879 poem in The Statesman depicting England, France, and India posthumously competing for Dutt's legacy (see Das 314–15).

But Dutt was not the only colonial writer to be claimed for British culture. Victorian feminists frequently used the rhetoric of New Womanhood to frame Indian authors as the products of their own educational efforts. Indeed, Priya Joshi shows, “the narratives of India and her women [would also] become sources of resistance and resolve for British women in their struggles for social and legislative equity at home” (193); to this end, Englishwomen “excavated the lives of remarkable Indian women” in order to advance their own agendas (176). In Sketches of Some Distinguished Indian Women (1891), Georgiana Chapman lauded the imperial “blessings of civilization and of education” for exporting “at least a share of that liberty and honourable respect which we are accustomed to consider as among the most valuable and incontestable ‘rights of women’” (2). Yet in a curious transition, she also stresses the more rapid “development of female education in India,” including the admittance of Indian women to the universities of Madras and Calcutta “before any English university . . . accorded [British women] the same privilege” (8). Chapman's pivot, Joshi argues, “works to generate possibilities for women in Britain” grounded in female advancement abroad (192), and suggests that like English literary education—which, Gauri Viswanathan has famously claimed, began in India—the origins of women's higher learning may lie outside the metropole. In 1919, Helen Woodsmall Eldredge would stress the portable potential of radical thought, enthusing that “the new woman of India” was distinct from “her sister, the zenana woman” (the inhabitant of secluded female domestic quarters) because her “new conceptions are revolutionizing old customs” (2). Three decades earlier, the Victorian critic Eliza Lynn Linton had accused “Social Insurgents” like Chapman of “trying to make the Hindus as discontented, as restless, as unruly as themselves” and faulted them for finding “no new field for British spades to till, no new markets for British manufacturers to supply” (598). Where Linton sought to extract resources and craft consumers, the “Wild Women” she targeted capitalized on global ferment to boost local bids for independence.

But even as they were subjected to British debates, reforms, and fantasies, many Indian women counterarticulated their own domestic and global ambitions. For this reason, the historian Tanika Sarkar has remarked, Indian feminism must be understood “as a modern Indian phenomenon, and not simply as a foreign implant” (“Gendering” 288). Many Indian women formed transnational connections and “affective communities” with cautious optimism, recognizing both the promises and pitfalls of international aid (Gandhi 1). Thus, Ramabai—a Hindu widow turned Christian convert and feminist activist—deployed the American educators Rachel Bodley and Frances Willard to raise funds for pedagogical initiatives in Pune and secured support from the British peeress Lady Dufferin for female medical care. But Ramabai worked not only on behalf of her countrywomen but also on behalf of Native and African Americans, whose exploitation she critiqued in an 1889 Marathi travelogue that also promoted American campaigns for female education.

While Partha Chatterjee has argued that the rise of Indian New Womanhood masked a nationalist “new patriarchy” (244), scholars like Sarkar, Bagchi, Shetty Parinitha, and Padma Anagol have conversely resuscitated “the agency, critical questioning, and resourcefulness displayed by . . . colonial Indian women as actors in the public sphere” (Bagchi, “Ladylands” 168). As Meenakshi Mukherjee first observed, “the question of women and their agency” would become central to the early Indian novel: a topic adopted by both men and women (82). But while nineteenth-century male novelists like Kandukuri Veeresalingam tended to “create the image of a modern woman based on the model of British women,” New Women often developed indigenized protagonists or used them to disrupt imperial norms (Rani 2). In an age of tumultuous social upheaval, many mined the full resources of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry to express changing opinions, aspirations, and self-conceptions. But because the novel became an especially popular medium of female self-expression—a vehicle unusually “accessible to marginal or subaltern groups such as women because of its still relatively non-canonical status” (Bagchi, “‘Because’” 60)—it is the primary focus of this essay.

Readers likewise exerted new agency and consumed literature in distinctive ways. For instance, Swati Moitra reveals, some nineteenth-century Bengali women practiced oral “communitarian reading,” countering the common “privileging of ‘silent’ reading as a ‘modern’ mode” (627). New Women also worked to cultivate readers’ interpretive capacities. Thus, the Brahmo writer Swarnakumari Devi Ghosal (sister of Rabindranath Tagore) titled her 1898 Bengali novel Kahake (which she translated into English as An Unfinished Song) to pose an open question—“To Whom?”—that recurs as the protagonist-narrator, weighing two objects of companionate attraction, finally “leave[s] it to the judgment of the reader to decide whom I have loved” (218–19). Authors signaled a specific orientation to female readers more and less explicitly: though Savitribai Phule's revolutionary Marathi poem “Rise to Learn and Act” (1854) opens by summoning her “brother[s]” among the “[w]eak and oppressed” to “[c]ome out of living in slavery,” its pedagogical rhetoric—“We'll teach our children and ourselves to learn / Receive knowledge, become wise to discern” (qtd. in Sardar and Paul 66)—evokes the schools for low-caste girls Phule had already cofounded. Here, readers became writers as teachers like Sagunabai and Fatima Sheikh shaped students like the fourteen-year-old Muktabai, who penned a scathing defense of the rights of Dalits (members of the lowest, “untouchable” caste) as a schoolroom exercise.

While Indian writers helped engender the New Woman avant la lettre, they were not alone. Periodizing this figure is a complex task: though first named in a heated 1894 periodical exchange between Sarah Grand and Ouida, the New Woman had already emerged abroad in recognizable forms. While the South African novelist Olive Schreiner is widely regarded as a progenitor, her 1883 Story of an African Farm trailed the Scots-Australian Catherine Helen Spence's Clara Morison (1854) and Mr. Hogarth's Will (1865), which framed colonial emigration as a potential vehicle of female liberation.Footnote 8 In the 1870s, Dutt was touted as an icon of New Womanhood (albeit without use of the uncoined term), while feminist opinion writing stirred the Indian periodical press as early as the 1860s and Phule published her trailblazing verse in the 1850s.Footnote 9 As Talia Schaffer notes, New Women's writing draws on a longer protofeminist literary history, which troubles attempts to distinguish Mary Wollstonecraft's Maria (1798) from Ella Hepworth Dixon's The Story of a Modern Woman (1894). But because, she shows, fears and fantasies of the New Woman became “one of the great causes of the 1890s” (731)—galvanized in the West by issues like contraception and the franchise—this self-consciously modern twist on the abiding “Woman Question” merits its own designation.

The rise of the Indian New Woman thus belies standard narratives of Western incipiency and colonial belatedness, freshly demonstrating the insufficiency of linear models of imperial influence. Networked and transimperial approaches to empire—long practiced by scholars like Srinivas Aravamudan, Elleke Boehmer (Empire and Indian Arrivals), Rimi Chatterjee, Rosinka Chaudhuri, and Daniel E. White—ground timely new appeals to “undiscipline” or “widen” Victorian studies (Chatterjee et al.; Banerjee et al.). These approaches are necessary, for instead of infusing “European forms” with local content, authors across the empire helped create genres like science fiction (see Chattopadhyay; Gibson) and sensation fiction (see Banerjee). Thus, literary modernity was invented not just “in Manchester or London but in Bhagalpur and Calcutta” (Gibson 12). Pondering why New Women regularly surfaced in the colonies, Jason Rudy has speculated that a heightened experience of otherness may have been wrought by the dual alienations of gender and empireFootnote 10—a point that aligns with Sarkar's claim that imperial gender norms placed Indian women under a “double negative teleology” (“Gendering” 286). Yet as Sarkar notes, many writers hardly accepted the double negative, but recognized their twin sources of oppression and critiqued their mutual reinforcement.

Scholars have identified transnational New Women from Japan, Korea, China, Egypt, and Jamaica, and among multiethnic American women.Footnote 11 Yet India's unusually extensive contributions to the creation of New Womanhood make the task of assimilating and augmenting existing research by specialists in its literature especially essential. Analysis should not be limited to Western languages, although—for reasons addressed below—that is the primary focus here. As Ulka Anjaria observes, anglophone literature emerged “in relation to and in dialogue with innovations in the bhashas [India's vernacular languages]” (7), yet as Aamir R. Mufti shows, English “clearly plays a disproportionate role in the circuits of circulation and validation of world literature” (18). Conversant scholars are thus needed to analyze fully still-understudied non-anglophone New Women like those excerpted in Tharu and Lalita's two-volume Women Writing in India: Six Hundred B.C. to the Present. This analysis may yield new discoveries among authors whose linguistic capacities or choices long inhibited their renown and may further expand our understanding of affinities and frictions between marginalized writers. For of the crush of female autobiographies that appeared from the mid–nineteenth century onward, Tharu and Lalita note, “nearly all” attest to “the tension and contradictions built into the promises liberalism held out to colonized peoples” (1: 160), while many feature accounts of hard-won literacy that recall contemporaneous slave narratives. Alison Chapman asks what it would mean, as an exercise in canon reformation, to “place Dutt at the centre of British Victorian poetry” (605). This essay poses a similar inquiry of the many Indian authors who helped invent modern feminism. Ultimately, decentering the presumptive whiteness of the New Woman will develop more accurately multifaceted accounts of a movement that emerged around the globe in strikingly diverse forms.

New Paradigms of New Womanhood

Works by Indian New Women tend to unsettle generic truisms. Though long seen as derivative of Anglo-American texts—shaped, per Priyamvada Gopal, “by European and Christian ideologies of self and society” (42)—their writings often implicitly destabilize or explicitly critique such ideologies. Moreover, they generate new paradigms. Western New Woman novels are pervasively pessimistic, Ann Ardis notes, and end almost universally in failure; as Schaffer has it, their authors “could diagnose what was wrong” but “could not imagine an alternative” (743). By contrast, Indian authors offer a wider range of responses to the “Woman Question,” capturing the pathos of the free-spirited, socially repressed modern woman but also highlighting the progressive potential of earlier eras, exploring tensions between individual ambition and collective uplift, and envisioning utopia. Many express interest in modernizing reforms while seeking to preserve local traditions, refusing to follow models set by British women or the literatures they exported.

Indian New Woman novels are also often frankly spiritual, particularly when written by converts to Christianity. While this is sometimes misrecognized as capitulation to British norms—and reason to regard them as less progressive than secular Western counterparts—life in the religious minority often amplified experiences of marginalization, shaping oblique positions from which to critique the status quo. As Deborah Logan notes, converts confronted “the orthodox attitude . . . that even prostitution was preferable to voluntary conversion” (xxi) and risked ostracization by audiences and acquaintances of different faiths (as Dutt found in Calcutta's conservative Hindu community [Lokugé, Toru Dutt xvi]). Whether they inherited or adopted religion, most did so intentionally, affirming Saba Mahmood's observation that piety should not be hastily dismissed as acritical or nonagential. As Anagol finds, many interpreted the Gospel as a useful tool of redress for “glaring inequalities between the sexes” that, they felt, Islam and Hinduism alike overlooked (27). On the other side of the globe, Christianity provided a similarly robust feminist framework for African American authors like Anna Julia Cooper and Frances Harper, who used it to infuse “liberationist discourses into the New Woman debate” (Beetham and Heilmann 5).

The gender politics of Indian New Womanhood likewise unsettles familiar tropes. Far from promoting an essentialist unity or inherent solidarity among women, some writers critique imperial women who condescend to teach without attempting to understand other cultures. Many stress the collusion of “Old Women” (mothers, aunts, grandmothers, and, above all, mothers-in-law) in perpetuating pernicious norms, immiserating themselves and their descendants. These women are often juxtaposed to sympathetic (if largely ineffectual) fathers who, humoring their daughters’ bids for independence, contrast with many a disapproving Anglo-American patriarch. These female intergenerational fractures partly align with the Western trope of the “revolting daughter” but often offer an additional imperial critique (Heilmann, “New Woman” 37n1). This conjunction, Roye argues, may have enabled Indian New Women to distance themselves from retrograde female forebears while quietly licensing their own “moral superiority” over Western women (77). This complex juggle involved, for instance, rewriting the figure of the sati (conceived broadly as a virtuous woman) on more progressive terms, particularly as colonizers narrowly reframed the sati as the self-immolating widow: an object of pity and condescension.

While the use of English by the novelists analyzed here potentially bespeaks class consciousness or Anglophilia, it may also reveal shrewd recognition of the emergence of a global lingua franca or a desire to identify a unifying vernacular (particularly in the wake of the 1860s Hindi-Urdu controversy over the choice of a national language). While imperialists and nationalists shared investments in the spread of English, so did radicals like Phule, who in 1854 urged readers to “Awake, arise and educate / Smash traditions—liberate!” (qtd. in Sardar and Paul 67) while using poems like “Mother English” and “English the Mother” to identify the language, Sunil Sardar and Victor Paul observe, as “a vehicle of [this] emancipatory education” (65). Deciding to write in English was, both in the moment and in the longue durée, deeply savvy: anglophone texts circulated more widely then and have received outsized attention ever since. At the time, colonial subjects were regularly rewarded for using English. In her 1890s prefaces to the early editions of Satthianadhan's first novel, Fanny Benson—the wife of a colonial administrator—transparently insists that because India's “vernaculars” are “too numerous” for “Englishwomen, as a class, to learn” (qtd. in Satthianadhan, Saguna ix), English enables a “freer intercourse with our Indian friends” (xii). Like Eldredge, she also frames the medium as central to an international movement that she encourages “Hindu women” to join: “English is the one language that will enable them to have intercourse with English women from the Himalayas to Cape Comorin, and which will open to them a world-wide literature, of present, as well as of past, interest” (ix). But naturally, anglophone dominance occluded from global currency authors who could not or would not use English. Presciently recognizing this asymmetry, Ghosal translated Kahake into English herself in 1913; by contrast, the more well-known Hossain's contemporaneous Bengali novel Padmarag would await translation until 2005. Like the disproportionate historical focus on the Bengal Renaissance (see O'Dell), this focus on English has distorted our picture of the era's literature. But linguistic hierarchies also inhibited the development of a fully intersectional Indian feminism. For ironically, fluency in European languages enabled Indian New Women to draw international attention to intersecting issues of gender, race, and imperialism while obscuring crises of caste and class—a point to which I return at the end of the essay.

Narrating the “Native ‘New Woman’”

Dutt's knowledge of European culture was deep. A polyglot native speaker of Bengali and student of Sanskrit, Dutt lived in France and Britain for four years, wrote fluently in English and French, and translated German. Yet Dutt's novels—long understudied in comparison to her poetry—qualify her apparently reciprocal infatuation with Europe. Both the French Le journal de mademoiselle d'Arvers (1879; The Diary of Mademoiselle D'Arvers) and the unfinished English Bianca; or, The Young Spanish Maiden (1878) emphasize their heroines’ tragic misalignment with social norms, identifying these tragedies as Western ones and thereby embedding a critique of supposed havens of liberalism and progress. Both feature protagonists who, bolder and wilder than their genteel peers, seem destined for unhappiness. Neither is Indian (Marguerite d'Arvers is French and Bianca Garcia half-Spanish and half-British), but both are conspicuously dark-featured, expanding the cultural parameters of the trope of the “dark unhappy ones” (Eliot, Mill 332). (These qualities may explain Gosse's contemporaneous account of Marguerite as “most characteristically Indian” [xxi] or Bagchi's more recent interpretation of Bianca as “a representation . . . of Indian heroines who likewise find themselves at a degree of remove from class-bound white British values” [“Analyzing” 190].) Across the diary entries that compose Le journal, Marguerite continually compares her own “black mass of hair” (Dutt, Diary 22) and “big black eyes” (47) with conventional beauties who are “all white” (21) or whose blond hair “seem[s] to form a halo round her head” (23). Though the filial duty and piety exhibited by Marguerite distinguish her from many Western New Women, she is recognizably intrepid. When rainfall disrupts a horse ride and her father tries to shield her, she laughs, scoffs “Am I scared of the rain?” (49), and gallops away. Marguerite's comparative erotic candor also marks her as “New”: entertaining at least two love interests, she uses charged language to describe their appeal. (This relative frankness about “l’éveil sexuel d'une jeune fille” [“the sexual awakening of a young girl”], N. Kamala conjectures, may have motivated Dutt's decision to write in French and hide the novel during her lifetime [109; my trans.].) The classically tragic ending anticipates a common fate of the Anglo-American New Woman: the death of Marguerite in childbirth is foreshadowed by premonitions she repeatedly raises with her husband and doctor, both of whom dismiss her as naive and emotional.

Distinguished by an oft-remarked masculinity, Bianca is identified as an outsider in England, where she resides with her Spanish father. Her features, insistently described as “dark,” make her “not beautiful” to others (Dutt, Bianca 267), and her “sooty complexion” (285) prompts her hostile mother-in-law to ask if her father has “Moorish blood in his veins” (281). Bianca embodies the paradox of Indian New Womanhood identified by Roye: though masculine and “independent,” she is also described as more “womanly” than her “childlike,” “dependen[t]” older sister (268). While their father prefers the dainty sister, he “looked on [Bianca] as his counsellor; sometimes he would even ask her advice in some important matter; ‘she was his right hand,’ he would say, ‘as good as a son to him; beneath her girl's boddice beat a heart as bold as any man's; beneath her wavy curls was a head as sharp and intelligent as any mathematician's’” (268). After Bianca brusquely rejects a man she does not love, she pursues her own desires and adopts a lover, Lord Moore. Yet affection hardly binds her: amused by Moore's insistence on walking her home, she shocks him by revealing a pistol hidden in her skirt. “She is a little wild,” he thinks, but concludes, “so much the better; she is as nature made her” (284). When Bianca apprises her disapproving father of the relationship, the “deep fire in her eyes” and her canny recollection of a prior incident force him to admit, “You behaved bravely then, Bianca . . . as bravely, as gallantly as any man” (291). Through rhetorical savvy and self-determination, she flouts convention and still achieves her companionate marriage. Yet the novel's incomplete conclusion appears bleak, for Moore departs for the Crimean War with the ominous parting words “if I never return” (381). Like Marguerite, Bianca has lived as an individual, but the victory is pyrrhic.

While these novels critique Western homogeneity, Dutt's narrative poetry identifies a more viable source for modern feminism in ancient India. In Ancient Ballads and Legends of Hindustan (1881), Dutt reworked oral Bengali culture and lionized heroines of Hindu mythology. Though this represented a “puzzling” shift from the “great disdain” with which she elsewhere described Hindu customs, as Meera Jagannathan shows (14), the ballads evoke a matrilineal dissension in the storied family's religious beliefs: while the first-generation male writers converted to Christianity in 1854, their wives largely remained Hindu (Chaudhuri 55). The collection opens with a longer ballad, Savitri, that retells the epic Mahābhārata legend of a princess who saves her husband's life by skillfully bargaining with Death—rewriting “a popular tale of Hindu wifely devotion” as the story of her strategy and strength (Stafford 40). Though she foregrounds the myth's ancient derivation, Dutt opens her version with a modern reference. Invoking the growing anti-zenana movement—fueled by Anglo-American women who made the critique of purdah a cause célèbre—Savitri rebuts British stereotypes of Indian women by advertising their more progressive past:

Though the tale was often conceived as the story of both Savitri and Satyavan—the central wife and husband—Dutt reframes it around the heroism of the heroine, as she does later with the goddess Sita, characterized no more as “gentle” but by the flames that “from her eyes shot forth and burned” (51). If Dutt presents exclusion, misperception, and tragedy as the likely end of the Western New Woman, she scours domestic myth to locate the origins of gender equity not in modern, anglicized India but in its Vedic past. Corresponding with Bader, Dutt highlighted this ambition, proclaiming: “the heroines of our great epics are worthy of all honour and love” (qtd. in Das 352).

Dutt was not alone in seeking autochthonous resources for Indian feminism in its ancient past; indeed, she participated in a wider reappraisal of the comparatively “elevated position of women” and the “equitable, though not equal, gender regime” in the Vedic “golden age” (S. Sen 146). Hossain reworked a different Mahābhārata episode to analogous feminist ends, while in The High-Caste Hindu Woman (1887) Ramabai portrayed the Shastras (Hindu scriptures) as more enlightened than their modern interpreters.Footnote 12 Describing “the early marriage system . . . of my country” (29) as one in which “women had equal freedom with men” (30–31), Ramabai stresses that it emerged “at least five hundred years [before] the Christian era” (29), clearly critiquing her adopted religion. Furthermore, she argues, while “[o]ur Aryan Hindus” bestowed an honor on mothers “without parallel in any other country” (51), the current “English government” colludes with “the male population of India” to repress modern women (67). Satthianadhan—who published widely in the periodical press on topics like “women's influence at home” and “female education”—cannily infused her own historical appeals with modern human rights rhetoric: “The ancient Hindus had far more liberal and generous ideas: they acknowledged the rights of women” and accorded “a great many privileges which are now denied to them” (Miscellaneous Writings 16). Yet tensions existed in this line of thought, particularly from those who confronted plural sources of oppression. As Tharu and Lalita recount, the Dalit student essayist Muktabai “scornfully rejects the tendency to go back to the Vedas [the oldest Hindu scriptures] for the answer to all contemporary problems” and “tells a story that gives a totally different understanding of the heroes of the Maharashtrian history” (1: 162).

In her novels, too, Satthianadhan embraced reform while addressing “Indian readers who might have desired a feminism they felt was advancing India's traditions, not defying them” (Lokugé, Saguna 11). Throughout her quasi-autobiographical Saguna: A Story of Native Christian Life (1895)—first partly serialized in the Madras Christian College Magazine (1887–88)—the protagonist-narrator thematizes her search for fulfilling, significant “work,” a term she repeatedly reprises. Saguna tracks the author's own extraordinary educational gains: one of fourteen children of Brahman (priestly caste) Christian converts, Satthianadhan earned a scholarship to pursue medical school in London; when forced by ill health to stay in India, she was among the first women admitted to the Madras Medical College, which she attended for a year before health constraints recurred. Her novel's similarly brilliant protagonist is masculinized from an early age, alternately roughhousing with her brothers and besting them at their studies. These activities mystify her conventional mother, who asks, “What is the use of learning for a girl?” and insists (in an apparent play on near homographs): “A girl's training school is near the chool (the fire over which everything is cooked), and however learned a girl may be she must come to the chool” (4). Nevertheless, Saguna persists in her scholarly ambitions, advocacy of “equal” marriage (89), and confidence in “defending my views” and “stand[ing] up for my rights” (154). Unflinchingly dismissing three arrogant professionals who propose marriage and a life of servitude, Saguna interweaves her critiques of gender and colonialism—for though each ostensibly modern man has just returned from England, none believes women should have “equal privileges with man” (207). Reversing Georgiana Chapman's qualified praise for the superior educational advancement of Indian women, Saguna applauds (perhaps ironically) the more “liberal spirit” of the English (207), yet simultaneously suggests, Priya Joshi argues, that education reform “needs to be initiated from within rather than applied from without if it is to avoid reproducing attitudes like those assumed by the England-retuned barrister, doctor, and student” (183). When Saguna finally marries, her husband celebrates her “restless, untamed spirit” rather than asking her to relinquish her “golden dreams of work and independence” (Satthianadhan, Saguna 219, 216). Saguna frames the path of its protagonist as arduous yet replicable; thus, Satthianadhan opens the novel by describing it as “a faithful picture of the experiences and thoughts of a simple Indian girl, whose life has been highly influenced by a new order of things” (1).

This “new order” and Saguna's search for meaningful work spurred the novel's reception as a tale of New Womanhood. Upon publication, the Victorian feminist Mary Frances Billington described Saguna as “a study of the ‘New Woman’ as she is in her Indian surroundings” and extolled the text's “vein of incisive satire” (qtd. in Satthianadhan, Miscellaneous Writings 123), while the British society magazine The Queen hailed its depiction of “the native ‘new woman’ beside the old.”Footnote 13 In The Woman's Signal, Florence Fenwick Miller staked a claim for British influence and canonical significance by likening the prose to Jane Austen's. Satthianadhan's fiction was printed at twice the usual rate and earned the admiration of Queen Victoria, who read Saguna and requested that the author's future work be sent to her (Priya Joshi 199). Though Saguna's rave reviews were not exclusively British, Englishwomen hastened to praise it. Yet if Benson's 1890s prefaces misread the novel as an endorsement of Western values and English education, Saguna engages with both primarily to critique them and repeatedly thematizes the vast experiential gulf between British and Indian women. In plot points especially curious for a convert like Satthianadhan, missionaries either feign interest in or reject Saguna outright: when she tries to bond with a missionary's daughter over literature, the girl scoffs, “You read? you can't read what I read. You won't understand,” and refuses to lend Saguna any books (Satthianadhan, Saguna 127). While her mother upholds racial hierarchies—“Don't you see the difference, they are white and we are black: we ought to be thankful for the little notice that they take of us” (128)—Saguna rejects such condescension. On visiting an English school, she resents the teachers’ patronizing gazes: “My old rebellious spirit rose within me. . . . I resolved that they should not see any difference between me and the other girls, and one day they would find that I was their equal” (169). The only fully positive cross-cultural engagement occurs in Saguna's transformative encounter with an American “lady doctor,” who prompts her to reflect:

[W]hat a world of untried work lay before me, and what large and noble possibilities seemed to open out for me. I would now throw aside the fetters that bound me and be independent. I had chafed under the restraints and the ties which formed the common lot of women, and I longed for an opportunity to show that a woman is in no way inferior to a man. How hard it seemed to my mind that marriage should be the goal of woman's ambition, and that she should spend her days in the light trifles of a home life, live to dress, to look pretty, and never know the joy of independence and intellectual work. The thought had been galling. It made me avoid men, and I felt more than once that I could not look into their faces unless I was able to hold my own with them. So like a slave whose freedom had just been purchased, I was happy, deliriously happy. (178)

Characterized as “a queer person,” the doctor is “the radical element in the institution” who “set at nought all its ordinances” (192). But while Saguna admires this quintessentially Western New Woman, she does not seek to follow her model—for, she insists, “I sincerely hope that my countrywomen, and . . . my countrymen also, in their eagerness to adopt the new will not give up the good that is in the old” (97–98).

Though the excerpt above echoes an analogous passage from Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre (1847), Satthianadhan's attempt to draw the attention of her “countrywomen” to “the restraints and the ties which formed the common lot of women” reveals her sharpest departure from British women's fiction. For in an enigmatic later episode, Saguna “devour[s], with intense delight, George Eliot's books” but finds that they prompt discomfiting reflections “on selfishness” (223). Here Satthianadhan distinguishes her work from novels (like Brontë's) that, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak has argued, often celebrate subjects presented “not only as individual but also as ‘individualist’” (116), or who eschew egalitarian projects for personal gain. In so doing, Roye shows, Saguna undertakes the great balancing act of the Indian New Woman: to define and defend a sense of self while selflessly uplifting others. Concerned that a desire to self-realize will lapse into irresponsible individualism, Saguna muses, “Was I not selfish even in my dreams of work? . . . I had longed for independence and a life of intellectual ease. What does a selfish being, a savage, do less than this?” (Satthianadhan, Saguna 223–24). This use of imperial rhetoric against her own ambition is puzzling, as is the novel's ending. Yet if its conclusion follows a conventional marriage plot, the novel's publication fulfills its own charge to “speak boldly to your countrywomen” (12). Satthianadhan thus uses fiction to continue the purposeful work she was obliged to relinquish in the realm of medicine, taking to print to articulate and disseminate claims—such as, “Probably very few people are fully aware how observant and critical girls are” (198)—on behalf of the broader group she represents.

Satthianadhan's next novel, Kamala: A Story of Hindu Life (1894), reprises and adapts the question of how to balance self-fashioning with collective betterment. Based partly on her mother's life, Kamala officially narrates the conversion of the daughter of a Brahman recluse into a traditional child wife. Yet as Grigg's 1894 preface recognizes, the novel also chronicles Kamala's “covert rebellion against injustice and domestic repression” and the “higher ideals and aspirations” that alienate her from contemporary mores (xxiv, xxxi). Though Kamala's achievements are less pronounced than Saguna's (she neither receives a formal education nor seeks a career), Grigg was right to diagnose the novel's overt critiques of practices like child marriage and the mistreatment of widows. Like Bianca and Saguna, Kamala is boyish and bookish: when a “grumbling old woman” gripes that her father “lets Kamala grow up like a boy. . . . She will tell you the contents of many books though,” Kamala is roundly mocked (Satthianadhan, Kamala 22). Marriage is framed as an imprisonment; deemed a “living grave” by another child wife (59), it arrives as a shock after a pastoral youth in which “[Kamala] felt free to do what she liked” (24). Though she sees “the extent to which a husband can tyrannize over his wife when he chooses to do so” (60), Kamala is consigned as “wife and . . . property” (26)—twinned terms that reappear later in the novel (119)—to a cruel, unfaithful man who, after first entertaining a companionate marriage, quickly comes to resent her “independent judgment” (170). Still, Satthianadhan brooks no neat binaries: as Mukherjee observes, both novels highlight “dialogic tensions . . . between religious dogma and independent questioning, between rigid social hierarchies and fluid identity, between colonial education and traditional wisdom, and between individual agency and the power of the community which can be alternately nurturing or claustrophobic” (73).

For ultimately—left widowed and newly childless, but furnished with an unexpected inheritance—Kamala dedicates herself to serving others. Her twin selflessness and self-possession converge when the longtime object of her affection, Ramchander (a man presented as her intellectual and spiritual equal), proposes, pleading:

It is the land of freedom I want you to come to. Have you not felt the trammels of custom and tradition? Have you not felt the weight of ignorance wearing you down, superstition folding its arms round you and holding you in its bewildering and terrifying grasp? . . . You will be free with me—free as the mountain air, free as the light and sunshine that play around you. Come, Kamala, make up your mind. . . . We shall create a world of our own. (Satthianadhan, Kamala 204–05)

Kamala does make up her mind but rejects the proposal, eschewing his utopian retreat in favor of undertaking hard work in the real world. Satthianadhan is palpably ambivalent on the merits of this ending, framing Kamala's rejection of Ramchander as both the “victory” of her “crude” religion and a form of liberation: “thus she freed herself once and for ever from the great, overpowering influence of the man before her” (207). As Roye contends, “Satthianadhan's depiction of an ideal widow neither confines itself to one doomed to coerced immolation, suicide, and prostitution, nor does it show one eager for remarriage, thereby thwarting Western stereotyping as well as indigenous male reformist projections” (79). Once “freed,” Kamala dedicates herself to social improvement. Spending “all her money in unselfish works of charity,” she is ultimately canonized as a “saint” whose “unseen hands still relieve the poor and protect the unfortunate; for she left her fortune for the sole benefit of widows and orphans” (Satthianadhan, Kamala 208). This final emphasis on the material legacy of Kamala's “unselfish works” and “unseen hands” echoes and rewrites the “unhistoric” life and “unvisited tomb” of Eliot's most famous heroine, Dorothea Brooke, whose own “incalculably diffusive” yet socially vitiated legacy concludes Middlemarch (1871–72; 785). To further confirm that Kamala is a “native New Woman” rather than a Western one, the novel introduces a foil who—described as “independent as a queen” (Satthianadhan, Kamala 92)—is ultimately exposed as mercenary rather than altruistic in her actions.

Satthianadhan's earliest interpreters understood that her turn to novel writing represented not a renunciation of “work” but a transformation of it. Citing the author's own plea during her illness to “[l]et me show that even a simple Indian girl can do something useful,” Grigg concludes: “This earnestness of purpose and the way in which she turned her talents to account in a totally different field, when she found that of medicine barred to her by ill-health, betokened surely something very like genius,—a readiness to do the work nearest to hand and her infinite capacity for taking pains” (xxviii). While she recruits Satthianadhan's novels to the British canon by deeming them “worthy to take rank among English Fiction,” Grigg also attests: “her wide and varied reading of English authors resulted in no servile imitation” (xxxiv, xxxv). Characterizing British and Indian women as engaged in a parallel, mutually beneficial “social revolution” (iii), Grigg uses Georgiana Chapman's Sketches—a work that helped introduce the anglophone public to Dutt, Ramabai, Sorabji, Anandi Joshi, and Suniti Devi—to adduce “how much there is in common in the waves of thought which have stirred the women of the East and the women of the West” (vii). But Grigg's and Chapman's praise of Ramabai was anticipated by Satthianadhan's own: in her essay “Pundita Ramabai and Her Work” (a title that recalls Saguna's emphasis on “work”), Satthianadhan valorized collective uplift anew: “Ramabai's work is national in its effects, for the widows that she is training are sure to take the lead in the emancipation of the women of India” (Miscellaneous Writings 95). Ramabai's efforts to educate widows, prostitutes, and orphans likely made her a model for Kamala's dedication to a similar population and to “that one great lesson, the great lesson of humanity, love for others and the need of doing one's duty at any cost” (57).

Though Ramabai hailed from Madras, her influence was indeed national, inspiring Bombay Presidency writers like Satthianadhan and Nikambé. Nikambé's now-obscure Ratanbai: A Sketch of a Bombay High Caste Hindu Young Wife (1895) advocates for female education, companionate marriage, and the improved treatment of widows by foregrounding the “persecution” of the smart, spirited Ratanbai and the immiseration of her aunt Tarabai, a widowed child wife (80). Though her father encourages her learning, Ratan's education is perennially threatened by a succession of matriarchs who, “educated in the old style,” are “most averse to ‘new or reformed ideas’” (22) and ask, “What good are we to get by educating these girls?” (30). The plot turns on the endless reasons devised for Ratan to miss school; the narrator tellingly remarks that through near-constant social obligations, “every young Hindu wife is . . . kept very busy” (49; emphasis added). When Ratan earns a scholarly prize in the wake of her husband's failed exams, “an elderly old-fashioned lady” (72) sneers: “Your husband has failed, and what do you want with school and prizes now? Pray to the gods, go to the temples and pay the vows, that he may have success” (72–73).

Of the authors surveyed here, Nikambé most sharply condemns women who reinscribe repressive norms instead of breaking with them. Yet Ratanbai also hypothesizes that “old-fashioned” women may simply be inhibited by a lack of education; when an important telegram arrives while Ratan and her father are away, her mother and aunt “could not make out anything,” for “the letters and the address were like Greek to them” (32). Men operate as less ambiguous agents of progressive change. The novel's happy ending, in which Ratan finally completes her education, is enabled by her enlightened husband, a New Man named Prataprao who champions her intelligence and calls her “his partner in life” (88). Similarly, Tarabai is saved by a chance encounter with a “Hindu reformer” who takes her under his wing (83). Ultimately, the novel promotes female emancipation as a collective endeavor that must involve men as well as women. Ratan's Kamala-like investment in mass uplift is, further, lent an idyllic matrimonial twist as Ratan and Prataprao, at the novel's end, “begin life together, recognising the responsibilities and duties which lie before them, and which concern not only themselves but their people and their country” (88).

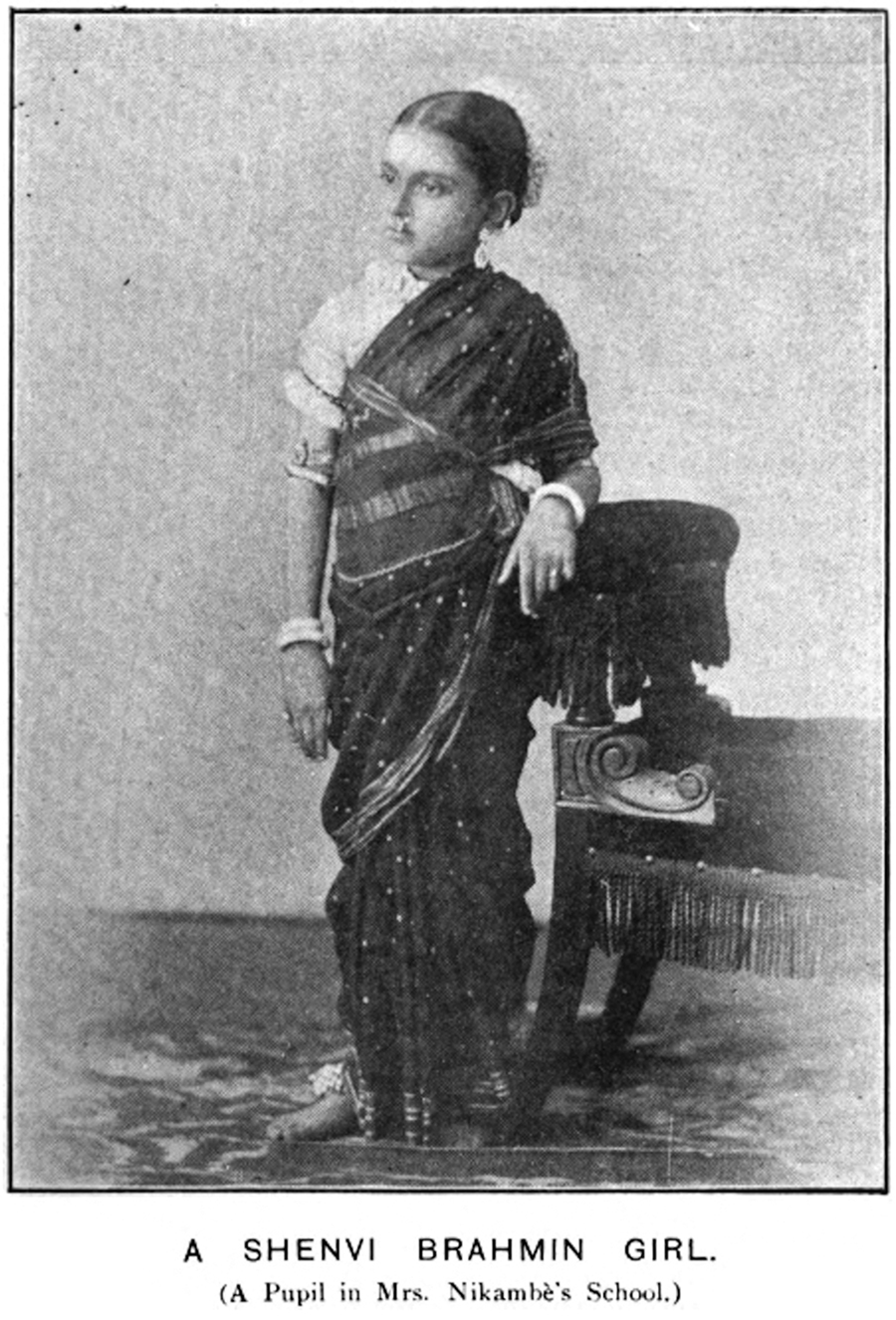

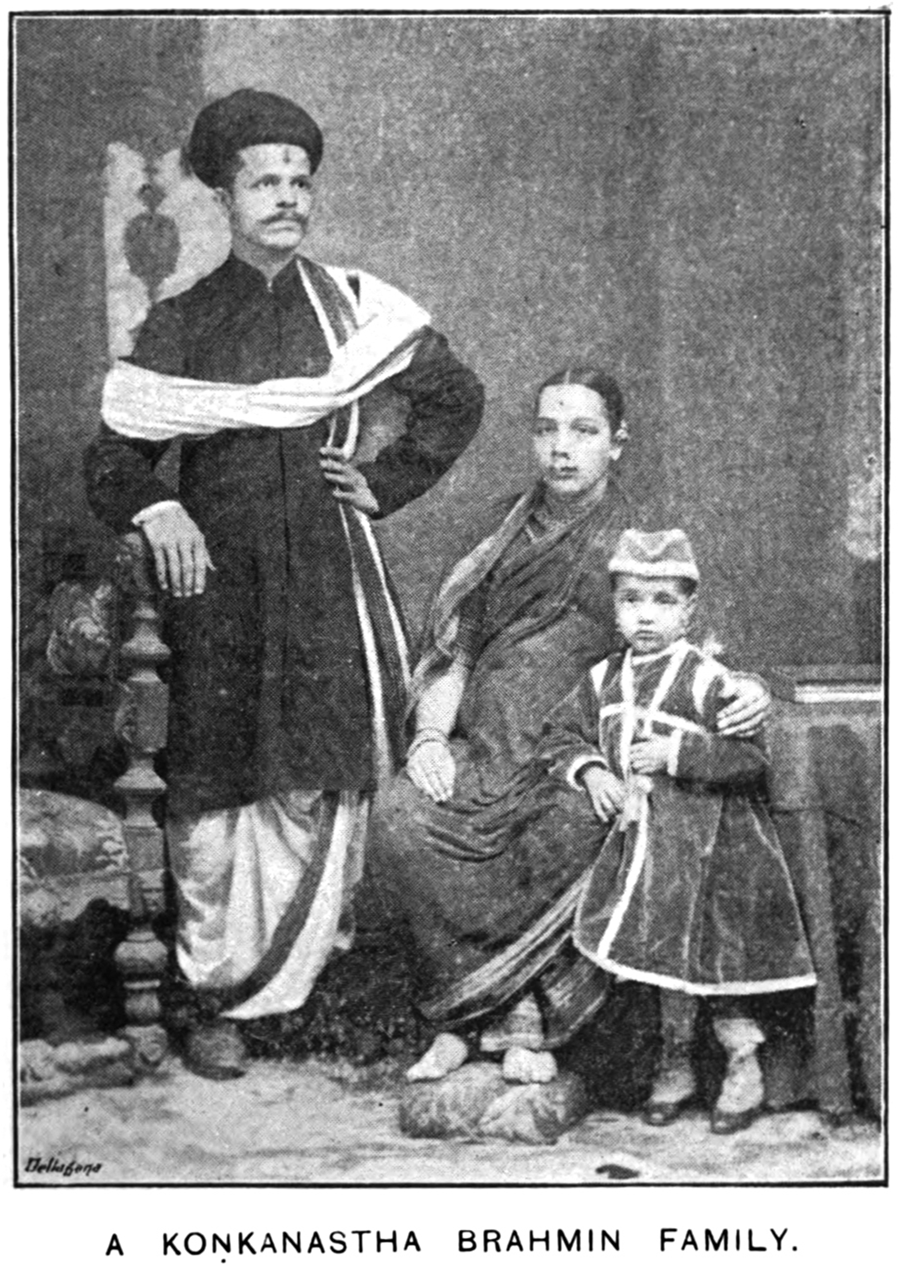

It is hard to glean Nikambé's intentions, given that Ratanbai is her only known novel and that most of her life story remains obscure. After helping Ramabai found a Mumbai girls’ school in 1890, Nikambé created her own “Hindu school for high caste girls” in Pune (v). Photographs tipped between chapters suggest Nikambé's apparent investment in caste distinctions: one depicts her pupil, elegantly bejeweled, identified as “a Shenvi Brahmin girl”; another introduces three members, royally posed, of “a Koṇkanastha Brahmin family” (figs. 1 and 2). Yet the novel tempers these glamorized visuals by distinguishing its main characters’ awareness of privilege: “aloof” and callous toward lower-caste women (50), Ratan's reactionary mother is negatively juxtaposed to her daughter, who treats them respectfully. Nikambé's relationship to her British patrons and proponents is more opaque. The novel opens with a dedication to “Her Gracious Majesty the Queen” and praises the British, “whose happy rule in my dear native land is brightening and enlightening the lives and homes of many Hindu women” (viii). Was this testament to colonial rule—echoing her similarly rosy stance toward New Men—heartfelt or strategic? While the novel remains enigmatic on the question, it further exemplifies the complex motives underwriting this understudied manifestation of the genre.

Fig. 1. An image from Nikambé's Ratanbai (end of ch. 1).

Fig. 2. An image from Nikambé's Ratanbai (end of ch. 2).

Perhaps nowhere are pessimistic Anglo-American fictions set in sharper relief than in the buoyant imaginary of Hossain, the Bengali Muslim autodidact, educator, and activist. In the English “Sultana's Dream” (1905) and the Bengali Padmarag (1924), Hossain portrays feminist communities in astonishing detail, as if generating blueprints for radical agendas. Both works present utopian collectives as necessary respites from the conventional household, perhaps reflecting the author's cognizance that “in India, a majority of women did not possess a home which they might call their own” (Ray 61). In “Sultana's Dream,” the eponymous narrator falls asleep in a Calcutta zenana but awakes in the utopic Ladyland, where the ideology of separate spheres has been inverted. Here, women not only lead pointedly public lives but control society, which they have holistically reoriented around a prescient investment in technology, higher education, air travel, electric vehicles, and solar energy. Meanwhile, the men of Ladyland—who, prone to violence and the fruitless expenditure of natural resources, once nearly ruined the world—are now confined to the mardana (the male equivalent of the zenana) and left responsible only for simple household tasks. Society has been kept safe from former threats to human and ecological life, and crime and warfare have been eradicated. To reprise Schaffer's terms, Hossain—unlike most Western New Women—could both diagnose social ills and imagine sweeping alternatives to them.

Hossain is now famed for her fictive representations of reversed purdah, yet her visions of female education—and the profound social revolutions she imagines education will entail—are equally radical. As Bagchi observes, her heroines are women educators whose community engagement is utopian yet deeply engaged with real-world politics; in her allegories “The Fruit of Freedom” (1921) and “The Fruit of Knowledge” (1922), “women's active participation in knowledge-making and action is seen as the sine qua non for overthrowing colonialism” (“Ladylands” 174). “Sultana's Dream” makes clear, Tharu and Lalita argue, that “[t]he tasks education has to equip women for . . . are the tasks of rebuilding the entire world” (1: 164), or at least, as Poulomi Saha has put it, of rebuilding a “political society in which virtue—a feminized condition—is the determinant of sovereignty” (244). Because, as Saha notes, “women's access to universal education has resulted in material, spiritual, and social goods for the collective and individual both” (244), it far exceeds the institutionalized, biopolitical formalities associated with Partha Chatterjee's nationalist “new patriarchy.” Padmarag's cooperative educational commune, Tarini Bhavan, is also (unlike Ladyland) multiethnic, comprising working women of varied races and religions who seek refuge from patriarchal oppression at home. Both works underscore the solidaristic basis of these endeavors, but Padmarag also adopts collectivity as a formal mechanism, dispersing the narrative into vignettes that canvass its characters’ diverse experiences. Like Kamala, Padmarag ends with the heroine's renunciation of marriage and explicit dedication to awakening and educating other women, reprising the frequently communal orientation of Indian feminist fiction and recalling Hossain's own social work in the slums of Calcutta.

The publication history of “Sultana's Dream” shows that debates continued as Indian New Women articulated competing ideals for achieving an egalitarian society. First published in The Indian Ladies’ Magazine, a journal cofounded and edited by the Tamil writer Kamala Satthianadhan (the second wife of Krupa's husband), Hossain's story prompted a critical counternarrative by the editor's daughter, Padmini Sengupta. In “An Answer to Sultana's Dream” (1905), Sengupta—who would become a prolific biographer of Indian New Women—rewrote the story's utopian community as “Gentleman-and-Ladyland,” freeing its men from the mardana and (like Nikambé) soliciting their participation in the project of placing “[m]en and women . . . on an equal footing” (qtd. in Logan 76). Yet Hossain's more far-reaching vision was also anticipated by India's first feminist historian, Bhandaru Acchamamba, whose 1902 Telugu writings envision a democratized, postcarceral state wherein “[p]olitical rights are equally given to men and women” and “there are no prisons and police since women look after [the] protection of people there” (qtd. in Rani 2). These imagined communities inverted contemporaneous misogynistic satires like Meye Parliament ba Dwitya Bhag Bharata Uddhara (1886; Women Parliament or Second Part of Rescue of India), in which a land ruled by New Women—and featuring a similar reversal of purdah—leads to a dystopian “collapse of the traditional social and moral order” (S. Sen 125). As these fictions and farces testify, Indian New Women preoccupied the popular imagination both at home and abroad, sparking fear or inspiration in those who encountered them.

Building an Intersectional Feminism

Educators and students stand to benefit from exploring the manifold influences on genre formation in an age of increasingly global cultural production. Future courses might reflect, for instance, the transformation of mystery and detective fiction by fin de siècle authors like Pauline Hopkins, E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake), or John Edward Bruce—all contemporaries of Arthur Conan Doyle—and also by the Bangla true crime writers unearthed by Shampa Roy (Gender and Criminality and True Crime Writings). Though many magazines and newspapers remain undigitized, educators may likewise profit from research by scholars like Logan, Priti Joshi, Amelia Bonea, Sukeshi Kamra, and Julie F. Codell, who highlight the rich periodical networks that flourished across nineteenth-century India and that facilitated (among other things) the emergence of feminist perspectives. Ideas for integrating these materials into courses on the “wide” nineteenth century are now well showcased in forums like Undisciplining the Victorian Classroom, the platform COVE (Collaborative Organization for Virtual Education), and V21 Syllabus and Handout Bank.

Anthologizers are likewise aided by increased digitization; in the third edition of the Broadview Anthology of British Literature, the New Woman is represented by Hossain, Sarojini Naidu, and Charlotte Mew. But as Tricia Lootens, Manu Samriti Chander, and Nathan K. Hensley have noted, such possibilities for expansion remain persistently underdeveloped in other mainstream anthologies. Those who study and teach the novel must also reckon with works less amenable to excerpting, yet texts themselves can be scarce. Editions of Indian fiction (and academic monographs on them) are often published by regional South Asian presses with more limited circulations, reinforcing canonical lacunae. Broadview Press has significantly expanded the New Woman canon to include lesser-known novels by (primarily) Western authors, but teaching editions of global New Woman narratives are also needed, particularly for the panoply of untranslated texts.

In Forget English!, Mufti asserts that “[t]he history of world literature is inseparable from the rise of English as global literary vernacular and it is in fact to the same extent predicated on the latter” (11). Many Western academics have, in recent years, weighed the possibilities and limitations of cross-cultural comparison and translation, stressing the potential for what Ming Xie identifies as “misrecognition” or “incommensurability” between linguistic and cultural systems (160, 13).Footnote 14 But some Indian scholars have recently found greater promise in the translation of marginalized texts into a global lingua franca; indeed, some posit, English translation may paradoxically afford the capacity to forget English or to “vernaculariz[e] the ‘master’ tongue” (Paranjape). As Pramod K. Nayar argues, the pursuit of a “cultural apparatus of human rights requires [both] English and translation,” for English can serve as a global “language of empowerment and emancipation” (23)—directing attention to previously unheard voices—while “[t]ranslation is what enables the use of a universal language of rights . . . to be ‘applied’ locally” (25). By specifically “democratising access to the work of hitherto disenfranchised women,” Bharti Arora adds, English translation may also facilitate a more genuinely intersectional Indian feminism—one “constituted by heteroglossia, pluralism, and cultural difference” (117, 114). In turn, she suggests, “women writers and/or activists” should use translation to not simply “engage in a dialogue across difference but also solidarize their asymmetrical subject positions” (111). This work started in the mid–nineteenth century with Phule, who anticipated more recent appeals to employ English as what Rita Kothari has called “a language of ‘Dalit’ expression.” Phule framed English as key to subverting elites like the “Mughal” (emperor) or “Brahman” (priest), insisting that “Mother English embraces the downtrodden / . . . [and] breaks shackles of slavery” (qtd. in Sardar and Paul 69).

But Phule's pioneering efforts to develop a “Dalit feminism” (Pan) would long await recognition. As Arora shows, the mainstream Indian feminism that was built by the authors surveyed here largely ignored caste and class issues or framed them as “secondary to a constructed unity in the name of sisterhood” (111)—a parallel to the calculated occlusion of race from mainstream Anglo-American feminism of the same era. Among these authors, Hossain most meaningfully sought to represent and engage multiply marginalized women, both in her writings and in her activism, and retained an optimistic vision of feminist solidarity across difference. “How is it that the same subject and sentiments swell up from places as diverse as Bengal, Punjab, Deccan, Bombay, and England?” she asked, conjecturing that “[t]he answer perhaps lies in the spiritual unity among the women of the British Empire” (xii). While Hossain's seamlessly international, intersectional feminism never materialized, the ephemeral conditions under which it felt possible warrant further exploration.