Scholars and policy analysts have sought to understand the relationship between popular support for Islamism, and political preferences such as support for democratic politics and Islamist militancy. Empirical studies testing these relationships have been inconclusive, either showing no significant relationship or presenting contradictory findings (e.g., Tessler and Nachtwey Reference Tessler and Nachtwey1998; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2002; Haddad Reference Haddad2003; Fair, Ramsay and Kull Reference Fair, Ramsay and Kull2008; Jamal and Tessler Reference Jamal, Masoud and Nugent2008; Kaltenthaler et al. Reference Kaltenthaler, Ceccoli, Gelleny and Miller2010; Tessler, Jamal and Robbins Reference Tessler, Jamal and Robbins2012). In this paper, we argue that these discordant empirical findings derive from vexatious challenges in measuring support for Shari`a in quantitative models. Scholars, usually forced to rely on existing data sets, tend to measure support for Islamism, defined as an ideology that locates political legitimacy in the application of the Shari`a, rather than specifying the meaning of this support because existing surveys tend not to ask respondents what Shari`a means to them.Footnote 1 Consequently, extant scholarship generally has not fully characterized respondents’ interpretation of Shari`a because analysts use variables that either reflect abstract patterns of support for a combination of religion and politics or, alternatively, support for very specific aspects of Shari`a. We argue that these partial operationalizations limit accurate measurement of important variation in respondents’ interpretations of Shari`a, which in turn affects scholar’s ability to accurately posit a relationship between support for certain interpretations of Shari`a, and support for democracy and Islamist violence.

In this paper, we attempt to make modest but important improvements in this scholarship by leveraging unique survey data that permit us to more robustly characterize the relationship between support for Islamism, and support for democracy and Islamist violence. We begin from the observation that a more accurate exposition of these relationships depends on an appreciation of the multi-faceted nature of Shari`a and concomitant operationalization of the concept. The larger concept of Islamism, defined as the political implementation of Shari`a in legitimizing legislation and governance, contains within it much variation in how to define Shari`a, including which aspects to emphasize and which individual or sectarian interpretation to implement. Thus, we argue for enhanced attention to expositing respondents’ varied beliefs about Shari`a as a means to more accurately operationalize Islamism and as a necessary precursor for measuring its support. Specifically, we examine how varying conceptualizations of an Islamic government, defined as one guided by Shari`a, relate to support for democratic values and support for Islamist militant groups among survey respondents in Pakistan. We focus on Pakistan, a predominantly Muslim country of over 196 million persons, because it is an extremely important country of study for both policy and epistemological reasons due to its checkered history of democracy and complex relationship with Islamism. Pakistan contains tremendous geopolitical relevance; it both uses Islamist militancy and nuclear coercion as tools of foreign policy, and has itself been a victim of Islamist terrorism, principally due to blowback from its erstwhile proxies (Fair Reference Fair2014; Paul Reference Paul2014). Epistemologically, understanding the ties between conceptualizations of Shari`a governance and political preferences with respect to democracy and Islamist violence in Muslim countries remains an important topic of scholarly inquiry.

To empirically address the challenges posed by the complex concept of Shari`a, we employ data derived from a carefully designed survey instrument that offers unique insights into how Pakistanis define a Shari`a-based government. Employing these data to conduct confirmatory principal component factor analysis, we identify two distinct components of Shari`a government in Pakistan: a transparent and fair government that provides for its citizens, and a government that imposes Islamic social and legal norms. We find that conceptualizing an Islamic government as one that implements Shari`a by providing services and security for its citizens is associated with increased support for democratic values, whereas conceptualizing an Islamic government as one that implements Shari`a by imposing hudud punishments (physical punishments such as whipping, stoning, cutting off hands, etc.) and restricting women’s public roles is associated with increased support for militancy. This result demonstrates that the relationship between Islamism and other preferences largely depends on how individuals within a particular context and time period construe a Shari`a-based government, and that Islamism is only an ideology associated with either democracy or violence when an individual defines it as such. Our findings also imply that future survey work on related topics should account for this complexity by more adequately capturing the multidimensionality of Shari`a in fielded survey instruments.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. We first highlight the theoretical ambiguity and measurement challenges in how scholars have previously operationalized Islamism and support for Shari`a. We then provide background on the history of Islam and politics in Pakistan, the context of our study, and outline our approach to more accurately conceptualize support for Shari`a that captures its multi-faceted and often contradictory nature. Next, we describe our data and empirical strategy, and turn to the results. We then discuss the implications of our analysis for the ways in which overly broad definitions of political concepts in surveys can mask important complexities and frustrate attempts to understand the ways in which these concepts relate to other politics preferences. We conclude with a discussion of the implications of these findings for future research and for policy.

Support for Shari`a: Measurement Issues

Shari`a is difficult to define and operationalize due to the significant pluralism that exists within any religious tradition, resulting in two innate divergences. The first divergence occurs between text and practice. Redfield (Reference Redfield1956, 70) articulates this as a division between a religion’s “great” and “little” traditions. The “great” tradition is the orthodox, textual, “consciously cultivated and handed down” tradition, while the “little” tradition can be described as heterodox, local, and popular, varying across groups and even individuals that may be considered part of the same larger faith tradition. This is not unique to Islam; all major world religions encompass both a written component as well as a varied practiced component. A second divergence occurs between the practiced traditions of religion. Practiced religion differs significantly across geographic and political contexts, within different sects, and even across individuals within any of these given contexts (Geertz Reference Geertz1971; Lukens-Bull Reference Lukens-Bull1999). In order to capture these divergences in one term encompassing all possible permutations of a religious tradition, Asad (2013 [Reference Asad1986]) argues that Islam is a “discursive tradition.”Footnote 2 Asad argues that any practices which relate themselves to the religious discursive tradition, however, this relationship is manifested, should be considered part of that religion.

Implicit in this description is the idea that while these varied practices draw legitimacy from the same discursive tradition, lived and practiced religious tradition will be heterogeneous and possibly contradictory across Muslims in different times, places, and communities. This multiplicity of practiced Islams has implications for defining Shari`a and Islamism in empirical work. The meaning of the term Shari`a has changed over time in both scholarship as well as in practice, from a type of legal training and learning process, to the institutionalization of specific Islamic legal institutions, to a more narrow approach limited to implementing specific and identifiably Islamic legal rules derived from the Qur̀an and the Sunnah (Brown Reference Bullock, Imai and Shapiro1997). Even the narrower contemporary definition of Shari`a differs across contexts and actors. Various definitions of Shari`a draw from any combination of prescriptions outlined in the Qur̀an and the Sunnah related to larger societal issues of politics, economics, justice, and social organization, in addition to personal issues such as sexual intercourse, hygiene, diet, and prayer (Schwedler Reference Schwedler2011). The complexities arising from the translation of a multiplicity of practiced and interpreted Islams is manifested in the diverse range of actors that can be described as Islamist, extending from those that advocate for quietism, effecting gradual political change through internal individual reform, to political parties advocating for societal reform through social welfare and electoral contestation, to revolutionary jihadis that seek to overthrow illegitimate states and implement revolutionary change. Islamists range from those who root justifications of their behavior in personal and literalist interpretation of the textual tradition, to those who rely on interpretations derived from human independent reasoning and decision making with a firm basis in established schools of Islamic legal theory. As such, there is little agreement among Muslims as to how a society based on Islamic law should be organized and governed (Kramer Reference Kramer1993).

Due to these theoretical complexities, scholars have faced difficulties in operationalizing support for Shari`a. Many studies aiming to capture respondents’ support for Islamism rely upon selective or stylized measurements of the underlying concept. Some scholars rely upon a general pattern of support for a combination of religion and politics, while others use very specific facets of Islamic law, rather than capturing the respondent’s personal definition or interpretation Shari`a. For example, in a sample of Lebanese citizens, Haddad (Reference Haddad2003) measures support for political Islam through a variable that combines a respondent’s support for militant violence, support for religious leaders holding public office, the perception of the Islamic state as the best political model, and the separation of religion and politics.Footnote 3 Muluk, Sumaktoyo and Ruth (Reference Muluk, Sumaktoyo and Ruth2013) measure support for Islamic law through a variable combining the respondent’s agreement with the following statements: an appropriate punishment for thieves is hand cutting, a woman cannot be president, it is inappropriate to wish Christians a “Merry Christmas,” people committing adultery must be stoned to death, and Muslims who convert to other religions must be killed. Tessler (Reference Tessler2002) employs multiple definitions of support for Islamic guidance in public affairs, drawing from varying survey instruments implemented in different Arab Muslim countries. One such operationalization includes the respondent’s opinion on whether men of religion should have a leading role in politics, agreement that Islam is the sole faith by which Palestinians can obtain their rights, and whether the respondent supports Islamic political parties and the establishment of an Islamic caliphate state. A second measurement used by Tessler asks whether religion should guide political, administrative, economic, and commercial affairs.Footnote 4 These studies under-specify or even mis-specify Shari`a, because quantification of support for the concept does not incorporate its multi-dimensional and subjective nature (Sartori Reference Sartori1970).

In many instances, it appears that scholars are instrumentalizing support for Shari`a using sub-optimal variables; scholars tend to do this when their choice of variables is limited to items on cross-national surveys that best proxy the concepts they wish to measure.Footnote 5 As we have noted above, a common baseline definition exists in academic explorations and practiced versions of Islamism: an ideology that assigns Islamic law a predominant role in legitimizing legislation and governance through the political implementation of the Shari`a. Yet, because Shari`a can cover a number of definitions and practices that vary across individuals, it is important to define and measure this term precisely—and in order to do so, scholars must ask surveyed populations what the concept means to them before they ask whether they support it. In the following sections, we outline a process through which we attempt to improve upon current methods of defining and measuring support for Islamism and Shari`a in the specific context of Pakistan, in order to better characterize its relationship with important—and opposing—political preferences.

Conceptualizing Support for Shari`a in Pakistan

Pakistanis have debated the meaning of Shari`a and what role it should have in the state since the country’s founding in 1947 (Rizvi 2000; Haqqani Reference Haqqani2005; Qadeer Reference Qadeer2005; Shaikh Reference Shaikh2009). While Pakistan’s leaders relied upon Islamism for state-building purposes, they never articulated a definition of Shari`a principally due to the plurality of interpretative traditions of Islam (masalik, plural of maslak) embraced by the polity. In addition to the Shīʿah maslak, which itself has multiple sects, there are four Sunni masalik: Barēlwī, Deobandi, Ahl-e-Hadith, and Jamaat-e-Islami (which is also a political party that purports to be supra-sectarian). Each maslak has its own definition of Shari`a and looks to different sources of Islamic legitimacy. With the exception of Ahl-e-Hadith, which follows no school of jurisprudence (fiqh), all Sunni masalik in Pakistan follow the Hanafī fiqh, despite other sources of differences and even (sometimes violent) disagreement (Rahman Reference Rahman2004; Abou Zahab Reference Abou Zahab2009; Reetz Reference Reetz2009). Apart from state-led forms of Islamism, Pakistan’s multifarious Islamist actors (i.e., political parties and militant groups) offer competing interpretations of Shari`a (Shah Reference Shah2003; Fair Reference Fair2011; International Crisis Group 2011). The multiplicity of competing interpretations of Shari`a has posed very real constraints on any meaningful implementation in Pakistan (Haqqani Reference Haqqani2005; Shaikh Reference Shaikh2009).

Defining Shari`a in Pakistan

While Pakistanis consistently demonstrate high levels of support for Shari`a in surveys (Pew Research Center 2012; Pew Research Center 2013), these surveys generally fail to adequately discern what Pakistanis believe Shari`a to be. To cast light on this issue, Fair, Malhotra and Shapiro (Reference Fair, Malhotra and Shapiro2010) fielded a survey that included a battery of questions to elucidate how Pakistanis conceptualize Shari`a and how they view the role of Islam in their state. Respondents were first asked, “How much do you think Pakistan is governed according to Islamic principles?”. Respondents were quite divided on this issue: nearly one-third thought that Pakistan was governed “completely” or “a lot” by Islamic principles, one-half believed that it was governed “a moderate amount” or a “little,” and 20 percent thought it was not governed at all by Islamic principles. Additionally, the vast majority of respondents (69 percent) indicated that Shari`a should play either a “much larger role” or a “somewhat larger role.” Only 20 percent thought it should play “about the same role,” and fewer than 10 percent believed that it should play “a somewhat” or a “much smaller role.” That survey also included a battery of questions about Shari`a to identify the components that Pakistanis include in this concept. More than 95 percent of respondents believed a Shari`a government is one that provides services, justice, personal security, and is free of corruption. In contrast, 55 percent believed that a Shari`a government is one that uses physical punishments. Given the generally positive attributes that respondents ascribe to Shari`a, it is not surprising that the minority see Pakistan as being governed under those principles and that they would like a greater role for Shari`a.

Pakistanis are not alone in characterizing an Islamic government in terms of good governance. In Afghanistan, one of the most important aspects of the Taliban’s operations is the provision of justice and ongoing efforts to delegitimize the Afghan government based upon its pervasive corruption. In fact, many ordinary Afghans have come to support the Taliban because of the corruption that they observed in the government (Abdul-Ahad Reference Abdul-Ahad2008). Collins (Reference Collins2007) finds similar motivations among Islamists and their supporters in the Caucasus and Central Asia, and a 2008 Gallup poll found that Muslims living in Egypt, Iran, and Turkey believe that Shari`a promotes the rule of law and justice (Rheault and Mogahed Reference Rheault and Mogahed2008). Thus, this notion of a Shari`a-based polity as one that is based upon good governance appears to hold in some form or another well beyond Pakistan.

The results from this earlier Pakistan survey suggest that at least two components—a person’s general preference for good governance, and a demand for a legal regime based on Qur̀anic principles of justice and punishment—are salient dimensions of Shari`a in Pakistan and should be incorporated into its definition when devising a measurement of support for Shari`a. We do not claim that these two components are universal in defining support for Shari`a (although the concept of Shari`a as good governance resonates in other contexts as well); indeed, it is most likely impossible to provide a universal understanding of the concept across the variegated polities in the Muslim world based on the above cited theories of religion and politicized religion. However, when we ask for definitions within a specific country, we do see systematic agreement about the components of Shari`a within the limited boundaries of a community. The combination of extensive knowledge of the context and a carefully designed survey instrument provides the information necessary to address important measurement issues in defining and operationalizing support for Shari`a within the Pakistani context.

Expectations Regarding Support for Shari`a and Other Political Preferences

The foregoing discussion about the definition of Shari`a in the case of Pakistan prompts questions about the relationship between various cognitions about Shari`a and important political preferences such as democracy on the one hand and support for Islamist militancy on the other. Existing empirical studies testing the relationship between support for Islamism and support for democracy and militancy generally find no significant consistent relationship (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2002; Fair, Ramsay and Kull Reference Fair, Ramsay and Kull2008; Jamal and Tessler Reference Jamal, Masoud and Nugent2008; Kaltenthaler et al. Reference Kaltenthaler, Ceccoli, Gelleny and Miller2010; Tessler, Jamal and Robbins Reference Tessler, Jamal and Robbins2012).

In terms of the relationship between Shari`a and democracy, several scholars have empirically tested whether various notions of Shari`a influence political culture, as suggested by early scholars of the Muslim world (Tessler Reference Tessler2002). Norris and Inglehart (Reference Norris and Inglehart2002) test Huntington’s “clash of civilizations” hypothesis using data from the World Values Survey to examine the effects of Judeo-Christian and Islamic religious legacies on cultural values. They find that the starkest differences are in terms of attitudes about gender norms and equality, not support for democracy (which is high across all surveyed populations). Jamal and Tessler (Reference Jamal, Masoud and Nugent2008), using first wave Arab Barometer data, show that respondents who favor secular versus an Islamic-based democracy exhibit similar levels of support for important aspects of democratic political culture such as pluralism and tolerance. Similarly, Tessler, Jamal and Robbins (Reference Tessler, Jamal and Robbins2012) find that both supporters and opponents of Islamism surveyed in the second wave of the Arab Barometer report high levels of support for democracy and democratic processes. To summarize, the existing literature does not demonstrate empirically a consistent pro- or anti-democratic effect of support for Shari`a.

Similarly, scholars have studied the relationship between support for Shari`a and support for Islamist political violence and have yielded discordant results. Some scholars have argued that while the relationship between religion and militancy is complex, religion can promote violence (Wellman and Tokuno Reference Wellman and Tokuno2004). Islam draws considerable attention because it is viewed as being particularly prone to violence.Footnote 6 Yet, as with the literature on preferences for democracy reviewed above, empirical investigations of this relationship yield varying conclusions. Scholars analyzing the relationship between individual support for Islamism and terrorism generally find no significant relationship. For example, in a sample of Pakistanis from 2007 and 2009, Kaltenthaler et al. (Reference Kaltenthaler, Ceccoli, Gelleny and Miller2010) find that individual beliefs about the extent to which Islam should play a more influential role in the world are unrelated to attitudes about the legitimacy of terrorist attacks on civilians. Additionally, a study in Pakistan by Fair, Ramsay and Kull (Reference Fair, Ramsay and Kull2008) found no relationship between views on Shari`a law and support for violence. However, scholars who stretch the concept of support for Islamist militancy to include more generalized anti-American and anti-Israeli sentiments generally have found that support for Islamism is associated with anti-American and Israeli sentiment (Tessler and Nachtwey Reference Tessler and Nachtwey1998; Haddad and Khashan Reference Haddad and Khashan2002; Haddad Reference Haddad2003; Kaltenthaler et al. Reference Kaltenthaler, Ceccoli, Gelleny and Miller2010; McCauley Reference McCauley2012).

The conflicting findings of the relationship between support for Shari`a and democracy as well as between Shari`a and support for Islamist violence may be due to the way that support for Shari`a is operationalized in these studies. If scholars’ measurements of Shari`a fail to capture multiple dimensions that may relate to political preferences like democracy and militancy in opposite ways, they may not observe important relationships between Shari`a and other preferences.

Returning to the particular case of Pakistan, we find that Pakistanis have two distinct—but sometimes overlapping—notions of Shari`a: one of a government that provides and one of a government that imposes. In light of the foregoing discussion of measurement issues in extant studies, these two understandings of Shari`a give rise to two testable hypotheses about the relationship between conceptualizations of Shari`a and support for democratic politics and Islamist militancy.

First, we hypothesize that conceptualizing a Shari`a-based government as one that provides good governance will be positively related to support for democracy.

Hypothesis 1: Respondents who understand a Shari`a-based government to be one that provides transparent services, justice, and personal security are more likely to support democracy.

While amenities such as transparency, justice, and personal security can be provided by non-democratic regimes, these preferences are most consistent with procedural aspects of democracy offered by Dahl (Reference Dahl1982) and later adumbrated by Schmitter and Karl (Reference Schmitter and Karl1991).

In 1982, Robert Dahl proffered several, generally accepted “procedural minimal” conditions that must be present for modern political democracy. These include stipulations such that constitutionally elected officials exert control over government decisions; citizens elect these officials in frequent, fairly conducted elections characterized by little or no coercion; there exists nearly complete adult franchise; citizens can freely express themselves without fear of retribution; citizens can pursue alternative sources of information, which exist and are legally protected; and that citizen have the right to form independent associations including political parties and interest groups (Dahl Reference Dahl1982, 11). Schmitter and Karl (Reference Schmitter and Karl1991) augmented this list with two additions, namely popularly elected officials must be free to exercise their constitutional powers without interference from unelected officials (i.e., military officers, entrenched civil servants, or state managers) and the polity must be self-governing and capable of acting independently. These procedural qualifications are salient in Pakistan where the military and the bureaucracy have directly or indirectly controlled the country since the mid-1950s. Despite these developments, Pakistanis nonetheless retain a preference for democratic forms of governance (Jalal Reference Jalal2007; Shah Reference Shah2014).

Our second hypothesis contends that conceptualizing a Shari`a-based government as one that imposes Islamic legal and social norms will be associated with greater support for Islamist militancy.

Hypothesis 2: Respondents who understand a Shari`a-based government to be one that imposes hudud punishments and restricts the role of women in public are more likely to support Islamist militant groups.

We posit this relationship because many Islamist militant organizations based in or operating from Pakistan embrace hudud punishments. For example, the Afghan Taliban, a long-standing Pakistan ally with sanctuary in Pakistan with whom Pakistani militant groups have collaborated since their inception in the early 1990s, were in power in Afghanistan and established a Shari`a government based upon their Deobandi interpretation of Shari`a. The Afghan Taliban, both in and out of power, have used hudud ordinances inclusive of stoning adulterers to death, whipping men and women who do not wear “Islamic” dress, and punishing men who shave their beards, among other physical punishments for such ostensible crimes. The Sipah-e-Sahaba-e-Pakistan (SSP, also known as Lashkar-e-Jhangvi or, more recently, Ahl-e-Sunnat wal Jamaat) and allied groups use similar rationale to kill Shīʿah, Barēlwīs, and Aḥmadiyyahs as well as non-Muslims arguing variously that they are hypocrites (munafiqin), apostates (muratid), polytheists (mushrakin), and non-believers (kufar), all of whom should be killed (Lashkar-e-Jhangvi 2008). Ostensibly, if one rejects hudud punishments as legitimate elements of Shari`a, one should also be disinclined to support the Islamist militant groups that embrace these punishments.

Data and Analytical Methods

To expand upon the exploratory Shari`a definition findings of Fair, Malhotra and Shapiro (Reference Fair, Malhotra and Shapiro2010) and to better understand how different conceptualizations of Shari`a government relate to support for democratic values (Hypothesis 1) and Islamist militancy (Hypothesis 2) in Pakistan, the research team fielded a face-to-face survey with a sample of 16,279 people. This included 13,282 interviews in the four main provinces (Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan, and Khyber Pakhuntkhwa), as well as 2997 interviews in six of seven agencies in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, or FATA (Bajaur, Khyber, Kurram, Mohmand, Orakzai, and South Waziristan). The survey was fielded in January and February 2012 in the four main provinces and in April 2012 in the FATA, an area that is home to numerous active militant insurgencies. Descriptive statistics of the sample are presented in Table 1. (For more details about the design and fielding of this survey, see appendix 1 in Fair et al. Reference Fair, Littman, Malhotra and Shapiro2016).

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics

Defining a Shari`a-Based Government in Pakistan

The survey instrument included a battery of six items aimed at developing nuanced understanding of respondent beliefs about a Shari`a-based government in Pakistan. The instructions read, “Here is a list of things some people say about Shari`a. Tell us which ones you agree with.” The enumerator then asked the respondent whether he/she agreed or disagreed that Shari`a government means:

∙ A government that provides basic services such as health facilities, schools, garbage collection, road maintenance.

∙ A government that does not have corruption.

∙ A government that provides personal security.

∙ A government that provides justice through functioning non-corrupt courts.

∙ A government that uses physical punishments (stoning, cutting off hands, whipping) to make sure people obey the law.

∙ A government that restricts women’s role in the public (working, attending school, going out in public).

These questions were intended to capture two distinct components of a Shari`a-based government: one that conceptualizes Shari`a as a non-corrupt government that provides services, security, and justice for its citizens, and one that conceptualizes Shari`a as imposing punitive interpretations of Islamic legal and social norms. To test whether this is indeed the case, we conducted a confirmatory principal components factor analysis. As shown in Table 2, the factor analysis revealed that the Shari`a questions do in fact load onto two distinct factors, which we refer to as “provides” and “imposes,” respectively. The “provides” factor accounts for 31.5 percent and the “imposes” factor accounts for 21.9 percent of the total variance, respectively. (For details of the factor analysis, see Online Appendix 1.)

Table 2 Rotated Factor Loadings for Shari`a Items

Note: The shading indicates the specific variables that load onto the two factors.

We created two index variables representing these factors, rescaled to range from 0 to 1. “Provides” captures the respondent’s support for defining a Shari`a-based government as one that is free from corruption and provides services, personal security, and justice. “Imposes” captures the respondent’s support for defining a Shari`a-based government as one that implements hudud punishments and restricts women’s role in public.

Figure 1 shows the percentage of respondents who report agreeing that each item is a component of Shari`a government. The vast majority of respondents agree that a Shari`a government is one that provides security, justice, and basic services, and is non-corrupt. Over half of respondents, agree that a Shari`a government is one that uses physical punishment to make sure people obey the law, and slightly less than half agree that a Shari`a government is one that restricts women’s role in the public sphere. Men and respondents who pray tahajjud namaz Footnote 7 were more likely to conceptualize a Shari`a-based government as imposing punitive interpretations of Islamic legal and social norms (p=0.000 for both), while those in urban areas and more educated respondents were less likely to endorse this view (p=0.009 and p=0.015, respectively). As shown in Figure 1, the mean of the “provides” index is 0.89 (SD=0.21) and the mean of the “imposes” index is 0.52 (SD=0.402).

Fig. 1 Item-wise support for Shari`a indices

At the individual level, viewing a Shari`a government as one that provides for the people and as one that imposes punitive interpretations of Islamic legal and social norms is not zero-sum. Instead, many respondents seem to hold both views at the same time. We bin respondents by their scores on both the “provides” and “imposes” indices (high=above the median, low=below the median; see Online Appendix 1: Table 4).Footnote 8 Nearly half of respondents are above the median on “provides” and below the median on “imposes,” while another quarter of respondents are above the median on both. Only 7.85 percent of respondents are below the median on both indices, suggesting that these two definitions do capture how most Pakistanis conceive of a Shari`a-based government.

Empirical Analysis and Results

Shari`a and Support for Democratic Values

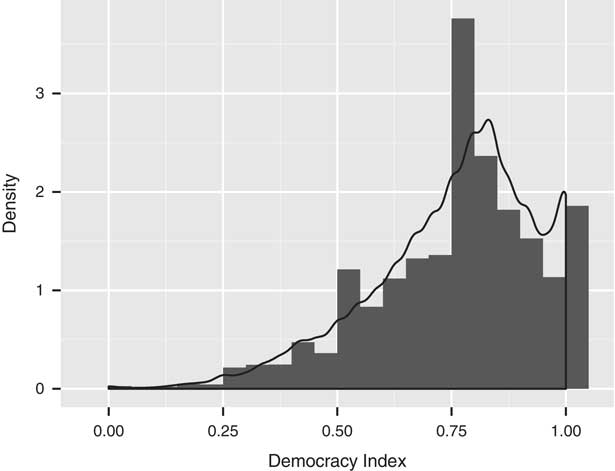

We use responses to six questions to assess respondent support for democratic values, following Freedom House (2011) and Fair, Malhotra and Shapiro (Reference Fair, Malhotra and Shapiro2013).Footnote 9 These items tap into important procedural and ideological components central to the concept of democracy.Footnote 10 While the concept of democracy is also complex and may be multi-faceted, a factor analysis confirms that the questions in this particular index capture a unidimensional concept of democratic values in Pakistan (see Online Appendix 2: Tables 1–2). We combined the six democracy questions into an index, scaled from 0 to 1. As shown in Figure 2, support for democratic values is high in this sample of Pakistanis, with scores on the index heavily skewed toward 1 (mean=0.75, SD=0.18).

Fig. 2 High level of support for democratic values among respondents

To evaluate Hypothesis 1 (i.e., to test how the two different conceptualizations of Shari`a are related to democratic values), we use ordinary least squares regression with standard errors clustered at the primary sampling unit (PSU) level. We estimate the following basic model:

where Y i is a continuous variable representing support for democratic values, D i a continuous variable for conceptualizing a Shari`a government as providing for the people, X i a continuous variable for conceptualizing a Shari`a government as imposing Islamic legal and social norms, α j district fixed effects, and ε i a normally distributed error term. We then add in a set of demographic covariates, including gender, age, ethnicity, formal education level, household expenditures, household assets, and indicators for head of household, urban location, able to read, and able to perform arithmetic. In a third specification of the model, we add additional religiosity covariates, including indicators for religious sect (Ahl-e-sunnat, Deobandi, Ahl-e-hadis, and Shīʿah), number of times the respondent prays namaz per week, and an indicator for whether or not the person prays tahajjud namaz.Footnote 11 In our final specification, we use tehsil instead of district fixed effects, in addition to the full set of demographic and religiosity controls.Footnote 12

Across all four specifications of our model, we find that conceptualizing a Shari`a government as one that provides for its citizens is positively associated with support for democratic values, whereas conceptualizing a Shari`a government as one that imposes hudud punishments and restrictions upon women is not statistically significantly related to support for democratic values (regression results in Table 3).Footnote 13 At the individual level, scores on both the “provides” and “imposes” indices seem to matter. Individuals who are above the median on “provides” but below the median on “imposes” are more supportive of democratic values than those who are above the median on both “provides” and “imposes” (p=0.005). In other words, individual respondents who believe that a Shari`a government is one that provides for its citizens are more supportive of democratic values when they do not also hold the view that a Shari`a government is one that imposes Islamic punitive legal and social norms. Individuals who are high on “provides” but low on “imposes” are more supportive of democratic values than individuals who understand a Shari`a government to be one that imposes Islamic legal and social norms but not one that provides better governance (p<0.001). They are also more supportive of democratic values than individuals who do not strongly conceptualize a Shari`a government as either providing or imposing (p<0.001).

Table 3 The Effect of Conceptualizations of Shari`a Government on Support for Democratic Values

Note: Ordinary least squares regressions predicting support for democratic values. Standard errors clustered by primary sampling unit (in parentheses). Shaded results highlight estimates corresponding to our hypotheses about conceptualizations of Shari`a government.

*p<0.10, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01 (two-tailed).

Shari`a and Support for Islamist Militancy

To measure support for Islamist militancy, the survey included questions on respondents’ level of support for two Pakistan-based, Deobandi militant groups: the anti-Shīʿah SSP and the Afghan Taliban.Footnote 14 Both of these groups have employed physical punishments, inclusive of killing those they deem to be worthy of death based on their interpretations of religious prescriptions. Enumerators asked respondents to indicate how much they support each militant group and its actions on a five-point scale ranging from “A great deal” to “Not at all.” We average responses to these two questions to get a direct measure of support for these important Deobandi militant groups (scaled from 0 to 1). We find that support for Islamist militancy is relatively low among respondents in this sample. As shown in Figure 3, mean support for SSP is 0.30 (SD=0.34) and mean support for the Afghan Taliban is 0.25 (SD=0.33).

Fig. 3 Low levels of support for militant groups among respondents Note: SSP=Sipah-e-Sahaba-e-Pakistan.

However, asking respondents directly whether they support militant organizations can be problematic in places afflicted by political violence. Item non-response rates to such sensitive and direct questions are often quite high given that respondents may fear that providing the “wrong” answer will threaten their own and their family’s safety. In this data set, non-response rates for the direct questions assessing support for SSP and the Afghan Taliban were 17.1 and 13.3 percent, respectively. Responses may be subject to social desirability bias, as respondents may answer in ways they think will appease presumably higher-status enumerators, rather than divulging their personal attitudes.

Therefore, we also used an indirect measure of support for specific Islamist organizations in the form of an endorsement experiment.Footnote 15 Endorsement experiments were first used in a conflict area to study support for political violence by Blair et al. (Reference Blair, Fair, Malhotra and Shapiro2013), and have since been used in other similar contexts.Footnote 16 In the survey, respondents were randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups or to a control group. Respondents in the control group were asked their level of support for four policies, measured on a five-point scale, recoded to lie between 0 and 1 for the analysis.Footnote 17 The research team identified policies for use in the experiment by closely perusing Pakistani domestic press accounts and conducting extensive pre-testing and focus groups. They selected four contemporary policy proposals that were relatively well known but about which Pakistanis were unlikely to have extremely hardened opinions: (1) plans to bring in the army to deal with the violence in Karachi; (2) “mainstreaming” the FATA; (3) using peace jirgas to solve outstanding bilateral disputes between Afghanistan and Pakistan including the conflict over the Durand Line; and (4) engaging in a dialogue with India over bilateral issues. Respondents in the treatment groups were asked identical questions about their support for these policies, but were then told that one of four militant organizations/people supports the policy in question (SSP, Pakistan Taliban, Afghan Taliban, Abdul Sattar Edhi).Footnote 18 This approach makes the policy, rather that the militant group, the primary object of evaluation. Since the only difference between the treatment and control conditions is the endorsement by the militant group, the difference in means between treatment and control groups provides a measure of affect toward the groups.

Consistent with the results from the direct questions, support for militancy is relatively low in this sample when measured using an endorsement experiment. Overall, the inclusion of an endorsement from a militant group seems to slightly decrease support for the policies in the endorsement experiment, although not significantly so (see Figure 3).Footnote 19 Thus, while Pakistanis in this sample express high levels of support for democratic values, they are not highly supportive of Islamist militant groups.

To test how the two conceptualizations of Shari`a government are related to support for militancy using the direct measurement (Hypothesis 2), we employ the same ordinary least squares regression strategy used above for democratic values. We estimate the following basic model:

where Z i is a continuous variable representing support for democratic values, D i a continuous variable for conceptualizing a Shari`a government as providing for the people, X i a continuous variable for conceptualizing a Shari`a government as imposing Islamic legal and social norms, α j district fixed effects, and ε i a normally distributed error term. Standard errors are clustered at the PSU level. In additional specifications of the model, we include (1) demographic covariates, (2) demographic and religiosity covariates, and (3) tehsil fixed effects plus the full set of demographic and religiosity covariates.

Additionally, we analyze the results of the endorsement experiment by estimating the following ordinary least squares regression model:

where P i is a continuous variable representing average support for the four target policies, T i a dummy variable representing assignment to any militant group treatment condition, D i a continuous variable for conceptualizing a Shari`a government as providing for the people, X i a continuous variable for conceptualizing a Shari`a government as imposing Islamic legal and social norms, α j district fixed effects, and ε i a normally distributed error term. Our key parameters of interest are β 3 and β 5, from which we can derive the marginal effect of conceptualizing Shari`a as providing for its citizens on support for militancy (β 3), and conceptualizing Shari`a as imposing Islamic legal and social norms on support for militancy (β 5). Because the endorsement treatment was assigned at the PSU level, standard errors are clustered at that level. In additional specifications of the model, we include (1) demographic covariates, (2) demographic and religiosity covariates, and (3) tehsil fixed effects plus the full set of demographic and religiosity covariates.

We find support for Hypothesis 2; those who conceptualize a Shari`a-based government as one that imposes Islamic legal and social norms are more likely to support Islamist militancy (Table 4). In contrast, we find no statistically significant relationship between conceptualizing a Shari`a-based government as one that provides for its citizens and supporting Islamist militancy. This finding is consistent across the direct measurement of support for militancy and the endorsement experiment, and is robust to a number of specifications of the model. At the individual level, those who are above the median on the “imposes” index are more supportive of militancy (p=0.000), regardless of their scores on the “provides” index (p=0.985). Thus, individuals who conceive of a Shari`a-based government as imposing hudud punishment and restricting women’s role in public are more supportive of militancy than those who do not, even if they also believe that a Shari`a-based government provides for its citizens.

Table 4 The Effect of Conceptualizations of Shari`a Government on Support for Islamist Militancy

Note: Ordinary least squares regressions predicting support for militancy. Standard errors clustered by primary sampling unit (in parentheses). Shaded results highlight estimates corresponding to our hypotheses about conceptualizations of Shari`a government.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 (two-tailed).

Discussion

Pakistanis hold two different, albeit not necessarily opposing, conceptualizations of an Islamic government guided by Shari`a. One conceptualization supposes a government that is transparent, fair, and provides services. The other articulates a government that imposes hudud punishments and restricts participation of women in civic life. These two conceptualizations relate differently to support for democratic values and support for militant groups in Pakistan. Disambiguating these differing conceptions allows us to reconcile some of the existing and discordant studies on these topics. On the one hand, conceptualizing an Islamic government as one that implements Shari`a by providing services and security for the people is associated with increased support for democratic values. On the other hand, conceptualizing an Islamic government as one that implements Shari`a by imposing hudud punishments and restricting women’s public roles is associated with increased support for militancy.

While these results—that liberal interpretations of Shari`a are correlated with general support for political liberalism and dislike of jihadi groups—may seem somewhat intuitive once articulated, this important distinction has not been made in existing literature largely because there has been no similarly exhaustive effort to identify respondent beliefs about Shari`a in a nationally representative sample in a predominantly Muslim country. This work underscores the potential perils of simply using survey items about general support for Shari`a as an independent variable to explore support for violent politics or democracy and underscores the need for detailed batteries about respondent beliefs about Shari`a in the countries of study.

These findings have important implications for the study of political Islam, and suggest that measuring popular support for Shari`a, a theoretically and practically complex topic, cannot rely on operationalizations of it as a unidimensional concept. Doing so limits scholarly understanding of Shari`a’s predictive power for a variety of attitudes and values. These partial operationalizations may explain inconclusive results in existing literature, as the lack of an accurate definition of Shari`a precludes scholars from knowing what their measurement of support means for the respondents. Recognizing and accurately capturing the multi-dimensional nature of the concept also may explain how of Shari`a is utilized by real-world actors for motivating and mobilizing various and seemingly contradictory forms of political behavior, ranging from violent and extrapolitical to peaceful and electoral.

Our findings also have import for survey research methodologies. Using overly broad or imprecise definitions of complex political concepts in survey instruments can ignore important complexities in political views. In our specific case, a political term that is commonly used and is highly relevant in contemporary politics is revealed, upon further analysis, to have at least two different meanings within the specific case of Pakistan. Measuring its support without understanding how individuals who engage with it politically would leave us in an analytical bind; a measurement of support would tell us little without subsequent questions about what the term actually means in a practical sense. But the issue of multi-dimensionality is not specific to Shari`a. Scholars constantly work with core concepts—including but not limited to democracy, authoritarianism, revolution, vote buying, and gender—that not only have multiple components to their academic definition, but which are heterogeneous in the way individuals live and experience, and thus define, these concepts.

Conclusion and Implications

Our analyses and results demonstrate that support for Shari`a, a theoretically and practically complex topic, should not be operationalized as a unidimensional concept. As with any type of government, Islamic governments can be conceptualized to perform a multitude of services. Individuals within the same political and national contexts can have different interpretations of what a Shari`a government actually means, and these varying definitions will change the way that support for Shari`a relates to other attitudes that policymakers and scholars find important. Nationally representative evidence from Pakistanis demonstrates important variation in their notions of Shari`a. Given that Muslim polities beyond Pakistan have some notion of Shari`a that is based upon aspects of good governance and service provision, researchers must be extremely careful in how they operationalize this complicated phenomenon. In future work, researchers need to understand what Shari`a means in the population that they are studying, and carefully design surveys and other research tools to accurately capture these definitions. We believe that while this work is a step in the right direction, the data employed here may also only partially exposit that facets that Pakistanis ascribe to a government informed by Shari`a. Additionally, both support for democracy and militant violence are likely multi-dimensional concepts that would benefit from greater exploration in a given context. Our results strongly suggest that this is an area that requires further research both in Pakistan and other countries.

With the caveat that this effort is a first step toward refining our understanding of these complex relationships, our findings do have implications for policymakers who rely upon extant, albeit less-than-optimal, measurements of Shari`a to predict adverse developments in a given country. With respect to Pakistan, policymakers have long feared that Pakistanis’ support for Shari`a indicates a preference for a kind of governance evidenced during the Taliban’s governance of Afghanistan. Worse, they have taken this to be a proxy for greater support for Islamist violence generally and violence aimed at American interests in particular. These fears, in part, motivate American preferences for greater secularism in countries like Pakistan. Our findings suggest that such reasoning is not only empirically unjustified, but may also be counterproductive.

Depending upon how individuals within a particular context and time period conceptualize a Shari`a-based government, public support for Shari`a can either be a positive force for democracy or a predictor of support for militant politics. Many of the existing assumptions about Islam posit a negative relationship with democracy, and suggest that secularized politics divorcing religion from the region’s political realm would be preferable. These assumptions also appear to undergird policy initiatives in the region. In reality, employing Islamic rhetoric and emphasizing the democratic aspects of Islamic law may be helpful in drumming up support for democratic values, as well as for related policies and programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jacob N. Shapiro and Neil Malhotra with whom the Pakistan survey study was developed and fielded. We also thank Christopher F. Gelpi and Mark Tessler as well as the various anonymous reviewers for their fine criticisms on earlier drafts of this paper. All errors are the authors’ own. The survey data employed herein was collected under a grant from the US Department of State, through the Office of Public Affairs, grant no. SPK33011 GR004. The authors also acknowledge support from the Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service and Security Studies Program.