Elections are frequently known for candidates and their supporters playing up the contest as a battle of “good versus evil” when it comes to policy outcomes. But the 2020 election took Manicheanism to a whole new level. Prominent evangelical Christian figures such as Jim Bakker, famous for the rise of “Praise the Lord” (PTL) in the 1980s, and others have spoken out regarding the calamitous times that were sure to come during a Biden administration—appeals that were accompanied, in some cases, with convenient sales pitches for food and other supplies to survive the impending apocalypse.

Bakker was hardly alone in his use of apocalyptic undertones in describing the stakes of the 2020 election. Writing for The American Prospect, Peter Montgomery reported how the rhetoric of the religious right helped to fuel the January 6th insurrection at the Capitol; megachurch pastor (and Trump advisor) Jentezen Franklin told those in attendance at an Evangelicals for Trump rally that their freedoms would vanish if Trump were not re-elected (Montgomery, Reference Montgomery2021). The degree to which such rhetoric has been employed in evangelical circles is so intense that an article appearing in Rolling Stone days before the 2020 presidential election declared Donald Trump the “end times president” due to support from evangelical Christian leaders who predict the “Second Coming” arriving sooner rather than later (Morris, Reference Morris2020).Footnote 1 And, as Gorski and Perry (Reference Gorski and Perry2022) observe, the Trump presidency witnessed an increasing degree of overlap between rhetoric surrounding the End Times and more secular conspiracy theories like QAnon.

Generations of scholarship investigating the extent to which religious elites are able to shape the attitudes and behaviors of those to whom they minister have made us cautious regarding assertions surrounding the likely effects that such statements had on the faithful. That is to say that religious leaders of any stripe often face significant impediments when it comes to guiding their flocks toward particular courses of action (see Djupe and Neiheisel, Reference Djupe and Neiheisel2022, for a review). We therefore might expect religious elites' efforts at encouraging people to physically prepare for the days ahead to have had little direct impact. But research on disaster preparedness has consistently found that exposure to a previous disaster is a strong predictor of future preparedness behavior (see Tierney et al., Reference Tierney, Lindell and Perry2001; Kohn et al., Reference Kohn, Eaton, Feroz, Bainbridge, Hoolachan and Barnett2012). And as Michael Barkun (Reference Barkun1974) points out, what constitutes a disaster is often open to interpretation and need not, of necessity, be natural (e.g., floods, hurricanes, etc.) in order to shape future attitudes and behavior (see Quarantelli, Reference Quarantelli1998, for more on this perspective). On the heels of a global pandemic and amidst a period of political and economic uncertainty, then, the 2020 elections may have elicited greater than usual levels of uptake of religious elites' suggestions surrounding the need to prepare.Footnote 2 That is, the circumstances surrounding our investigation into the relationship between religious variables and preparedness activities may have triggered what has been described as “a sense of apocalyptic time” (Gribben, Reference Gribben2009, 163) wherein a normally quietist impulse among End Times believers is overridden.

In this paper, we therefore ask: What are the determinants of preparing for disaster in the wake of the 2020 elections? If it is the case that Christian conservatives were led to prepare for the End Times, then we ought to see preparedness behavior track with a host of religious variables, including Christian nationalism, apocalypticism, church attendance, and (as a moderator) the belief that Christians are being persecuted in the United States. Although our design is not wholly up to the task of pinpointing whether elite rhetoric causally encouraged the faithful to prepare for hard times ahead, we expect greater exposure to religious messages (as proxied by a measure of church attendance), to correspond to greater levels of preparedness, conditional on the belief that the end is nigh. Moreover, we are able to explore whether holding attitudes that are consistent with the messages that have been heard from some Christian right elites track with preparedness behavior.

Religion and preparedness behavior

Religious variables are not normally among the predictors that are associated with preparedness activity (Tierney et al., Reference Tierney, Lindell and Perry2001), even though some research has shown that very religious individuals are more likely than the less religious to engage in some types of preparedness behavior, such as participating in shelter-in-place drills (Citizen Corps, 2009; Bian et al., Reference Bian, Liang and Ma2022).Footnote 3 Other work has also found Mormons to be better prepared than members of other faith traditions (Rothlisberger, Reference Rothlisberger2008; McGheehan and Baker, Reference McGheehan and Baker2017). The degree to which members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the LDS Church) are, on average, better prepared than most for many different kinds of calamities likely stems from core tenets of the LDS Church's teachings, which call adherents to be ready to face adversity (McGheehan and Baker, Reference McGheehan and Baker2017).

But religious beliefs have often been found to provide a barrier to effective disaster preparedness. For instance, in Sun et al.'s (Reference Sun, Deng and Qi2018) systematic review of the disaster response literature, they point out that Muslims in Bangladesh, in believing that floods are “an act of Allah,” are therefore also likely to “believe that they cannot and should not do anything to prepare” (592) for such an event. Indeed, religious leaders across a host of different faith traditions promote an understanding of disasters as divine retribution that is likely to discourage their flocks from engaging in disaster preparedness activities (Joakim and White, Reference Joakim and White2015). Similarly, it was clear from McGheehan and Baker's interviews with people of the Bahá’í faith that “preparing for long-term recovery from a catastrophic event was not part of their ideology” (Reference McGheehan and Baker2017, 271). They also found evidence to suggest that “Buddhist values of impermanence and acceptance may lead to a passive approach to disaster preparedness” (McGheehan and Baker, Reference McGheehan and Baker2017, 271). Recent work by Fetterman et al. (Reference Fetterman, Rutjens, Landkammer and Wilkowski2019) also found “doomsday prepping” to be only weakly related to a belief in God. And among Christians in particular, even beliefs about the apocalypse—the precise nature of which can vary quite a bit depending on the theological views to which one subscribes—might not necessarily imbue believers with a sense that they need to physically prepare for the End Times.

Preparing for the apocalypse

In spite of the fact that many Christians in the United States hold “compelling theological views about the end of days,” the available research suggests that apocalyptic beliefs do not always track with levels of physical preparedness for disasters (Albertazzi, Reference Albertazzi2011, v). To be sure, preparing for an eventual apocalypse is not unknown among Christian groups. Latter-day Saints, for instance, have been counseled for decades to have a year's storage of food and other supplies to prepare for either short-term personal economic struggles or natural disasters. Some prominent LDS members have also taken the view that it is also needed to prepare for the end of the world, even if such a viewpoint is scant among the church's higher ranks of leadership (Yorgason and Robertson, Reference Yorgason and Robertson2006). There are certainly church members, though, who use fear of the apocalypse to instill the need to prepare by buying goods.

Some elements of the evangelical Christian community have likewise embraced preparedness when prompted by a wide variety of events or potential events. External events, such as the Y2K bug as the year 2000 approached (see Gribben, Reference Gribben2009), terror threats and resulting wars, or natural disasters, all prompted some to urge preparations for the End Times (McMinn, Reference McMinn2001; Cowan, Reference Cowan2003).Footnote 4

And it is worth noting here that many millenarian movements have emerged in the aftermath of disasters, broadly understood. For instance, a series of “climate-related crises in Europe,” including one that took place in the 1640s, corresponded with an uptick in the production of apocalyptic sentiments (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2021, 17). Other scholars, such as Michael Barkun (Reference Barkun1986), credit a period of economic uncertainty with ultimately giving rise to millenarian groups such as the Millerites in the 1840s. As Barkun notes in another work, “natural catastrophes, demographic shifts, the rise and fall of cities, alterations in the status system, economic depression, industrialization – all might constitute disaster” (Reference Barkun1974, 52).

For the most part, however, even those who hold apocalyptic beliefs often have historically focused more on spiritual preparedness than they do on physically preparing to ride out the apocalypse, at least in one qualitative investigation of the subject (Albertazzi, Reference Albertazzi2011). The logic articulated by Barker and Bearce (Reference Barker and Bearce2013) would seem to suggest that those who hold to an apocalyptic worldview indeed should be less likely to prepare for disasters, regardless of the circumstances. Although they applied their argument to environmental attitudes, the idea that a belief in a short time horizon (in this case, that the world could be coming to an end sooner rather than later) suppresses support for enduring near-term costs that bear the promise of future benefits would appear to be portable to the context of disaster preparedness. After all, this line of thinking has pervaded evangelical thought for some time, and is believed to have discouraged much in the way of political involvement among some of the early figures in the “Old Christian Right” (Ribuffo, Reference Ribuffo1983). Even minimally preparing for a disaster can be a costly endeavor, as having the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)-recommended three days' worth of food and water on hand, in addition to other supplies such as a first aid kit or an emergency radio, involves a short-term investment that might seem foolish to those for whom the “shadow of the future” is also short.

During “normal” times, we might expect those who express high degrees of apocalypticism to engage in just such a thought process. However, disasters—natural, political, or otherwise—may engage a sense of apocalyptic time for some believers. There are those who would argue that apocalyptic beliefs are omnipresent with the End Times—being “psychologically present as the motive for the believer's efforts” (McGinn, Reference McGinn1994, 15). But experience with disaster may inspire a greater than normal uptake of suggestions to prepare for hard times ahead.

Recent survey research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic has shown that there is a link between “doomsday prepping” and associating COVID with a “doomsday scenario” (Smith and Thomas, Reference Smith and Thomas2021). It nevertheless remains unclear as to what extent apocalypticism more generally is associated with disaster preparedness activity amidst a period of upheaval.

The apocalyptic strand of white Christian nationalism

Christian nationalism is a worldview that may magnify the role of religious beliefs in portending apocalypse. As Gorski and Perry describe the concept, “White Christian nationalism is a ‘deep story’ about America's past and a vision of its future. It includes cherished assumptions about what America was and is, but also what it should be” (Reference Gorski and Perry2022, 3). With a strong vision of what America is and whom it is for, Christian nationalism is therefore laced with apocalyptic undertones when elites point out gulfs from that vision (Gorski, Reference Gorski2017; Gorski and Perry, Reference Gorski and Perry2022). As evidence, Gorski and Perry (Reference Gorski and Perry2022) show that belief in the existence of Armageddon and the Rapture is tightly correlated with Christian nationalist sentiments.

They also argue that the narrative that Trump sold to the American public shares much in common with the apocalyptic strand of white Christian nationalism (Gorski and Perry, Reference Gorski and Perry2022, 84–85). Fear stokes the flames of Christian nationalism with various religious figures asserting that one (typically Democratic) politician's actions are anti-Christian, while at the same time arguing that Trump can lead America back to being a great and proper Christian nation (Whitehead et al., Reference Whitehead, Perry and Baker2018). Various Christian figures used that rhetoric to whip up support for Trump in opposition to Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton (for a review, see Trangerud, Reference Trangerud2022). That rhetoric coupled with a fear that Democrats would persecute Christians also led to continued support for Trump by Christian nationalists in the 2020 presidential elections (Perry et al., Reference Perry, Schnabel and Grubbs2021). And, as Robbins and Palmer (Reference Robbins, Palmer, Robbins and Palmer1997) note, groups that view themselves as facing persecution may feel the need to prepare for confrontation.

Gorski (Reference Gorski2017) points out that some evangelicals surely saw Trump as “the lesser of two evils.” For others, however, Trump's vision of America as a crumbling nation that exists as a shadow of its former self, a vision that was on display throughout his inaugural “American carnage” address, surely resonated with the kinds of apocalyptic narratives to which some evangelicals subscribe (see Mattson, Reference Mattson2017). Indeed, the “millennial myth” is closely intertwined with various flavors of nationalist ideology in the United States (see Maclear, Reference Maclear, Mulder and Wilson1978) and, according to Lamy (Reference Lamy1992, 409), “acts as a powerful metaphor for concrete social structure and for real human events. It provides cognitive meaning for believers and a context in which to interpret current events and give meaning and direction to people's lives.”

This vision is also seen in pitches that Jim Bakker, Alex Jones, Glenn Beck, and others gave to their followers in recent years. Their message was not one where there is plenty to go around as America basks in God's favor. Rather, their view is that society will collapse and that the goods that we are used to buying at the grocery store just will not be available. Instead of preparing followers in a religious sense, many of this “new breed” of millenarians—those who have much in common with the “Survivalists” of the 1980s—might very well have adopted the motto that “God helps those who help themselves” (Lamy, Reference Lamy1992, 419). To get through the dark times, followers of Bakker and of the self-styled, modern-day prophets who he often promotes on his show need to buy meal kits, bulk food, have plenty of fresh water on hand, and make other preparations for the coming tribulation (Mazza, Reference Mazza2017). Judgments surrounding the likelihood of needing to prepare for disaster—however defined—are highly contextual in nature (McMinn, Reference McMinn2001; Cowan, Reference Cowan2003) and can be influenced by risk perceptions (Tierney et al., Reference Tierney, Lindell and Perry2001). Possibly in response to elite statements to the effect, Christian nationalists may therefore have seen their vision for the country slipping away after the 2020 elections, constituting a “disaster event” for some.

We therefore might expect Christian nationalism to drive preparedness behavior. On the other hand, research on Christian nationalism has often noted that ascribing to Christian nationalist beliefs has a greater effect on Americans' attitudes than it does their behavior. For instance, Christian nationalism has been found to predict negative attitudes about pornography, but has no impact on self-reported consumption of pornography (Perry and Whitehead, Reference Perry and Whitehead2022). It remains to be seen, however, whether a similar gulf between attitudes and behavior emerges in the context of preparedness activities.

We argue that beliefs about the impending end of the world (apocalypticism) may correlate with being physically prepared as well. While a truncated “time horizon” may inhibit support for costly short-term investments, such as disaster preparedness, during “normal times,” events that convince those who hold a comprehensive set of beliefs surrounding the End Times that the world has entered into “apocalyptic time” may track with greater degrees of preparedness activity. Perspectives on apocalypticism which emphasize the idea that such beliefs are always accessible, in psychological terms, would likewise predict that apocalyptic attitudes are likely to track with greater levels of disaster preparedness (McGinn, Reference McGinn1994; see also Robbins and Palmer, Reference Robbins, Palmer, Robbins and Palmer1997). Whatever the mechanism, it is clear to us that apocalypticism is likely positively associated with disaster preparedness activities. We also expect preparedness behavior to track with apocalypticism more closely for those who attend religious services more frequently under the theory that those who frequent houses of worship are more likely to encounter the types of rhetoric typified by the Jim Bakkers and Jentezen Franklins of the world.

Data and measures

Measures appropriate to capturing the concepts in play are not typically gathered in omnibus survey efforts like the GSS or ANES, though the ANES included preparedness questions in several surveys, though without appropriate religious variables for our inquiry. Instead, we gathered our own data through a survey of nearly 3,600 Americans supplied through Lucid in March 2021.Footnote 5 We used raking weights conditioned on gender, age, education, and race to match Census estimates. All results are weighted.

The preparedness measures were extensive and two-pronged. The first set asked about activities undertaken, including (coded 0 = no and 1 = yes):

• Put together emergency supplies like water, food, or medicine kept in your home.

• Changed any part of your home to protect it against wind, flooding, or other natural disasters.

• Practiced what to do if there is an emergency when you are at home.

• Volunteered to help your local community prepare for or respond to an emergency.

• Taken first aid training such as CPR to keep someone breathing or resuscitate someone.

• Made a plan for how you and the people you live with would communicate in an emergency.

• Decided on a place for the people you live with to meet if they cannot go home in an emergency.

• Bought insurance to protect you or your property against a disaster.

The second set asked about supplies kept on hand: a radio that is battery operated or hand-cranked; a first-aid kit; at least three days' worth of canned or dried food for each person who lives in your home; a flashlight; extra batteries for a radio or flashlight; at least three days' worth of medicine for anyone in your household who would need it; at least six months’ worth of canned or dried food for each person who lives in your household; the ability to grow your own fruit and vegetables, and have a source of fresh meat that could provide for everyone in your household if grocery stores were closed. These were coded 0 = no/haven't thought about it, 1 = yes. We should note that the vast majority of these questions were taken verbatim from a similar battery designed by the Department of Homeland Security and administered on two waves of the 2008–2009 ANES panel as well as on various iterations of the Citizen Corps survey (see also Sattler et al., Reference Sattler, Kaiser and Hittner2000). For our analyses, we combined the two scales. The combined analyses produce very similar results to analyses using the individual supplies and activities scales.Footnote 6

The other particularly salient measurement discussion concerns apocalypticism, which is the set of beliefs that supernatural forces of good and evil are active in the world, headed toward a final showdown in the end times. This operationalization tracks well with the definition of “catastrophic millennialism” put forth by Wessinger (Reference Wessinger, Robbins and Palmer1997), in which “Evil is seen as being rampant, and things are believed to be getting worse all the time” (49). “Further,” she continues, “it is believed that the catastrophic destruction is imminent” (Wessinger, Reference Wessinger, Robbins and Palmer1997, 49; emphasis in original). For this measure, we included two scales (of evil and prophecy) and one single measure (end times). The items scaled well at α = 0.85. The belief in active evil combines three measures asking if “There is evil out in the world,” if “The devil exists,” and whether “We must make every effort to avoid sinful people.” The prophecy scale was also composed of three items: “God reveals his plans for the future to humans as prophecy”; “God has given some people the power to heal others through prayer and the ‘laying on of hands’”; and “God is in control over the course of events on Earth.” The end times measure was simple, asking if “We are very likely entering the prophesied ‘end times.’”

We also asked questions on our survey that are appropriate to measure Christian nationalism (see Whitehead and Perry, Reference Whitehead and Perry2020) and beliefs surrounding the persecution of Christians (see the Appendix for full variable coding). In addition, we placed several items on our survey geared toward capturing other elements that might track with preparedness behavior, including civic skills—an organizational ability often linked to higher rates of political participation (e.g., Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995).

Results

Perhaps because of the COVID pandemic, Americans admit to a considerable amount of preparedness supplies and activities.Footnote 7 Figure 1 shows that the median American has at least five of the supply types on hand, though Republicans have one more type than Democrats and independents. Preparedness activities are less commonly engaged, but almost everyone has done something on that list—Democrats a bit more than the others.

Figure 1. Amounts of preparedness in supplies and activities in the United States.

Source: March 2021 Survey.

Note: Median lines shown.

Likewise, apocalypticism is common among Americans, skewed a bit high by the near universal belief that there is evil in the world (see Figure 2)—most everyone believes there is evil in the world (83%), though fewer admit that the devil exists (62.5%). Still, it is perhaps remarkable just how many people believe in prophecy and supernatural involvement in worldly affairs—20–30% agree with those statements. Similarly, about 30% believe that we are in the prophesied end times. Right around 60% of the sample scores above 0.5 on the apocalypticism scale—Americans are disposed to see the world in black and white with a confrontation of supernatural forces on the horizon.

Figure 2. Distribution of apocalypticism and its components.

Source: March 2021 Survey.

It is worth noting that apocalypticism is not just an evangelical Protestant phenomenon, but instead cuts across American religion. We find apocalypticism in all major religious traditions (see Figure A3 in the Appendix), even if it is somewhat more common among evangelicals and non-denominationals. The median mainline Protestant, Catholic, and Black Protestant are not far behind the median evangelical.

Models of preparedness

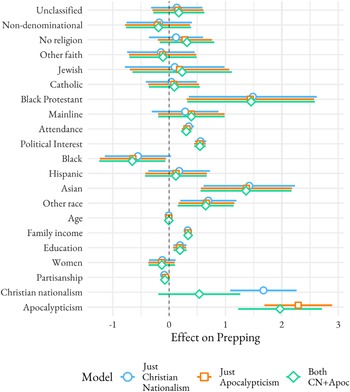

To help isolate the relationship of apocalypticism to preparedness, we start with a well-specified model that includes partisanship, political interest, religious traditions, worship attendance, and demographics. The results are shown in Figure 3 (for numerical results, see Appendix Table A2), which includes a comparison of effects with and without a measure of Christian nationalism (the six-item Baylor index used by Whitehead and Perry, Reference Whitehead and Perry2020). The effects for the most part do not budge when Christian nationalism is included, though the effect of apocalypticism weakens slightly. Still, the model suggests that the effect of Christian nationalism is insignificant, while apocalypticism is strong and positive, boosting the preparedness index by more than two points.

Figure 3. OLS estimates of preparedness, comparing estimates with and without Christian nationalism.

Source: March 2021 Survey.

Note: 95% confidence intervals shown. For the numerical estimates, see Table A2.

Apocalypticism has one of the strongest relationships with preparedness in the model, with only political interest, income, and worship attendance coming close (all positive and significant). After controlling for income and apocalypticism, it is notable that partisanship is negative—Republicans prep at lower rates, though as we saw above, a sizable share of independents are quite ill-prepared for an apocalypse.

The model suggests that correlates of political participation are involved in preparedness—resources (e.g., income), ideological mobilization, and mobilizational channels (such as involvement in congregations). Indeed, political participation itself is linked to preparedness and does not diminish the other coefficients, which suggests that some degree of external input from society is important in motivating preparedness. This is no surprise because the measure of preparedness involves not just concern but action. We'll explore next whether apocalypticism is sufficient inspiration or whether its effects are contingent on some degree of mobilization.

Interactions: with attendance?

As a classic measure of social capital correlated with political participation (e.g., Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wright Austin and Orey2009), worship attendance is an obvious variable to explore the potential contingencies of apocalypticism. From the same model shown above, we estimated an interaction term that suggests that the effect is contingent on attendance as shown in Figure 4. Only with above average attendance is apocalypticism significantly linked to greater degrees of preparedness. But since attendance is a proxy for so many things—hearing more from clergy, engagement with other people and the community, and opportunities to gain skills (see Djupe and Gilbert, Reference Djupe and Gilbert2009)—only further analysis can help us sort out what this result means.

Figure 4. Interactive effects of apocalypticism with attendance on preparedness.

Source: March 2021 Survey.

Note: Comparing any two confidence intervals is the equivalent of a 90% test at the point of overlap.

Interactions: with civic skills?

Including a measure of civic skills in the model weakens the effect of attendance by a third and is itself strongly linked to preparedness. It also produces an interaction similar to that seen for attendance—with above-average skills (~2 of 4), apocalypticism is linked much more strongly with preparedness, boosting the index by 2.5 points compared to just 1 point for those with below average skill levels (see Figure 5). This confirms that apocalypticism produces action when the worldview is married with civil society involvements that reinforce that view and mobilize it. It also suggests that the attendance result is likely about the civic benefits of involvement, rather than exposure to elite rhetoric.

Figure 5. Interactive effects of apocalypticism with civic skills on preparedness.

Source: March 2021 Survey.

Note: Comparing any two confidence intervals is the equivalent of a 90% test at the point of overlap.

Interactions: with persecution beliefs?

One story to emerge from the Trump years is the extent to which Christian persecution grievances were widely aired, especially by Trump himself. A number of surveys, including ours, asked these Christian persecution questions, asking both if the respondent believed these claims as well as whether they have “heard or read anyone making the following arguments in the past few months.” As of early 2020, a fifth of Americans thought that Democrats would ban the bible (Djupe and Burge, Reference Djupe and Burge2020), a figure which grew across the election cycle. It would seem reasonable to expect that apocalyptic believers who have heard such arguments would prepare a little harder.

The evidence perhaps supports that expectation (see Figure 6). There is a small bump in preparedness by about 0.75 index points among those who heard an above-average number of Christian persecution claims (left panel). We suspect that the effect is only modest because apocalyptic believers are highly likely to report that they've heard them—Christian persecution is not news to them. Shifting to panel b where we examine the interaction with believing that Christians will be persecuted, we see a somewhat different pattern. Apocalypticism maintains its strong link to preparedness, but the interaction shows that believing Christians will be persecuted is somewhat more demobilizing for those who are not apocalyptic believers. Believing in Christian persecution is not more mobilizing for strong apocalyptic believers—it is baked into their worldview already. But, by and large, Christian persecution claims are not adding much to explanations of preparedness, surely because this is almost constant among apocalyptic believers.

Figure 6. Interaction of apocalypticism and hearing about and believing in forthcoming Christian persecution.

Source: March 2021 Survey.

Note: Comparing any two confidence intervals is the equivalent of a 90% test at the point of overlap.

Interactions: with partisanship?

We worried that preparedness behavior might be conditional on being a Republican given the degree to which the apocalyptic rhetoric was flying among their elites and mass. After all, since 2016 the Republican standard-bearer—Donald Trump—has engaged apocalyptic rhetoric on the campaign trail, calling the 2016 contest with Hillary Clinton “a moment of reckoning” (qtd. in McQueen, Reference McQueen2016). However, our evidence suggests that partisans were drawing on a well of religious belief (see Figure 7). That is, partisanship does not interact with apocalypticism to shape preparedness behavior. But perhaps this makes sense. Democrats and independent apocalyptics could hear talk from Trump and others on the right and likewise assume that a battle between good and evil was coming, if perhaps they disagreed about who—that is to say, which party—is on which side.

Figure 7. Apocalypticism's link to preparedness is not moderated by partisanship.

Source: March 2021 Survey.

Note: Comparing any two confidence intervals is the equivalent of a 90% test at the point of overlap.

Interactions: with Christian nationalism?

Christian nationalism and apocalypticism are not independent, making an exploration of their interaction worthwhile. The two variables are strongly correlated, but there is variance across the scale such that there are combinations of high and low Christian nationalists across the apocalypticism scale. The expectation is that these two forces work together to produce more action. If Christian nationalism is, at root, a firm governing ideology in which Christians are granted a rightful place of power in a country blessed by God, then anything threatening to that romanticized view is likely to spur a considerable reaction. The threat comes with the belief that evil is active in the world and a period of tribulation lies ahead.

The evidence in Figure 8 suggests that apocalypticism has stronger effects on preparedness as Christian nationalism grows. At low levels of Christian nationalism, apocalypticism has only a slight positive, but statistically insignificant estimated effect. But at higher than average levels of Christian nationalism, apocalypticism has a much stronger effect, adding almost 3 scale points in preparedness.

Figure 8. Apocalypticism's link to preparedness is boosted by Christian nationalism.

Source: March 2021 Survey.

Note: Comparing any two confidence intervals is the equivalent of a 90% test at the point of overlap.

We also thought to check whether this effect is conditional on race. In what seems like a growing amount of writing about Christian nationalism, authors shift the discussion to suggest that it is a worldview that is only effectual (or problematic) among whites (e.g., Gorski and Perry, Reference Gorski and Perry2022; Rubin, Reference Rubin2023). Rubin (Reference Rubin2023) is a good example—fueled by a Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) report she suggests that white Christian nationalists are in a panic because, “This group feels besieged because they are losing ground.” That seems like the precise inspiration for preparedness that we are discussing.

However, the results (see Figure A4) suggest no interaction—Christian nationalism contributes no additional preparedness beyond what is driven by apocalypticism—for whites and Asians. Only for Blacks and Latinos are Christian nationalism scores important in fueling preparedness among apocalyptic believers and those scoring low in Christian nationalism do not see a rise in preparedness with greater apocalypticism. While there are broader dynamics in play, it seems clear that the racial dynamics of Christian nationalism are not well understood nor easy to assume.

From preparedness to “prepping”: the special case of guns

The ownership of firearms and other weapons is rarely something that is encouraged as an element of a broader orientation toward disaster preparedness. The “prepper” community, on the other hand, often places a premium on stockpiling arms and ammunition (see Fetterman et al., Reference Fetterman, Rutjens, Landkammer and Wilkowski2019; Mills, Reference Mills2019; Smith and Thomas, Reference Smith and Thomas2021) in anticipation of a long-term survival situation in which they may need to be armed in order to protect themselves, their families, and their “preps” (stores of food, water, medicine, and other essentials), and provide food from wild game, if necessary. And while there is some research that has connected firearm ownership with religious variables (e.g., evangelical Protestant affiliation, theological conservatism, and belief in a supernatural evil) that are likely adjacent to or overlap considerably with the understanding of apocalypticism that we employ in this paper (Yamane, Reference Yamane2016; Vegter and Kelley, Reference Vegter and Kelley2020), it is worth investigating whether apocalypticism helps to shape what might be understood as an orientation toward stockpiling guns.

Figure 9 shows that as apocalypticism increases throughout its range the probability of reporting an intention to buy a gun in the near term increases as well.Footnote 8 This is true for those who do not own a gun as well as for those who report already possessing a firearm. Among those who already own a gun, however, increased levels of apocalypticism appear to substantially boost the probability of intending to buy a gun within the year. Although far from determinative, that apocalypticism radically increases the likelihood of seeking out another gun purchase among those who are already gun owners suggests that some degree of (weapons) stockpiling behavior may be associated with a comprehensive set of beliefs surrounding the end of the world.

Figure 9. Apocalyptic gun owners are much more likely to buy more guns.

Source: March 2021 Survey.

Note: Comparing any two confidence intervals is the equivalent of a 90% test at the point of overlap.

Conclusion

Previous research has generally found that religious beliefs are poor predictors of individual preparedness activity, in spite of the focus that many of the faithful place on the end times (Albertazzi, Reference Albertazzi2011). End times believers, it seemed in previous work, often placed more emphasis on preparing their souls rather than on stocking their pantries in anticipation of the coming apocalypse. In this paper, we sought to re-investigate this connection amidst renewed rhetoric among evangelical religious elites, like Jim Bakker, on the importance of being physically as well as spiritually prepared (see also Gribben, Reference Gribben2021). Such rhetoric is easily dismissed as self-serving, both to his bottom line (he was, after all, selling prepared foods through his show's web store) and to his political aims, but it is a possibility that apocalyptic rhetoric from Bakker and others encouraged those who similarly hold such beliefs to prepare for the worst surrounding the 2020 elections.

In following that elite rhetoric, we were led to ask a set of questions that have only sporadically been asked or have never been asked before to create an index of apocalypticism that is clearly well subscribed among Americans. All told, the combination of supernatural involvement in this world, belief in both forces of active good and evil, as well as anticipation of their confrontation constitute apocalypticism—a worldview prone to extremes that can justify all manner of activity when the stakes are everything (see also Wessinger, Reference Wessinger, Robbins and Palmer1997). At its most mundane, however, apocalyptic believers store extra food and batteries and make plans for when the great battle arrives and supply chains are even more disrupted than they were in 2022. This finding marks a departure from previous studies that have found little to no role for religious variables—and, in particular, for end times beliefs—in predicting preparedness behavior (see Albertazzi, Reference Albertazzi2011; see also Fetterman et al., Reference Fetterman, Rutjens, Landkammer and Wilkowski2019).

Much to our surprise given the demonstrated role that it plays in predicting a host of other attitudes and behaviors (though see Perry and Whitehead, Reference Perry and Whitehead2022), we find only conditional evidence here that Christian nationalism is related to physical disaster preparedness measures. We suspect that the null effect may relate to the fact that apocalyptic beliefs are so tightly bound together with Christian nationalism. But, apocalyptics without a strong sense of Christian nationalism do not show preparedness at high rates. This is an element of a broader critique of the conceptualization and measurement of Christian nationalism that has been leveled in recent research. As Davis (Reference Davis2022) points out, Christian nationalism incorporates numerous undercurrents, both empirically and theoretically, in such a way that “anything resembling conservative expressions of religious-political belief appears to be evidence of ‘Christian nationalism’” (Davis, Reference Davis2022, 3; see also Smith and Adler, Reference Smith and Adler2022). In some iterations of Christian nationalism as a theoretical construct (e.g., Gorski, Reference Gorski2017; Gorski and Perry, Reference Gorski and Perry2022), apocalypticism is one constituent part of what it means to be a Christian nationalist, even though any of the explicit measures that we use here are not included in the most commonly employed survey measures of Christian nationalist sentiments. However, the inclusion of an explicit measure of apocalypticism, as we do here, makes it clear that beliefs surrounding the End Times, and not Christian nationalism as a broader construct, are primarily driving preparedness behavior.

This is not to diminish the importance of understanding Christian nationalism, but rather to urge future research to start disentangling how key components of the construct relate to various outcomes of interest. We suggest that apocalypticism is important in its own right and is both theoretically and empirically separable from concepts like Christian nationalism that cast a wide net in an effort to capture the nexus of faith and politics. Surely more research is warranted on how apocalypticism relates, not just to preparedness behavior, but also to policy attitudes and other features of the political world (see Guth et al., Reference Guth, Green, Kellstedt and Smidt1995 for an early application).

In the end, though, our results raise questions about why it is that apocalypticism tracks with physical preparedness behaviors, in spite of the fact that previous studies have argued that those who believe in the existence of an impending apocalypse should eschew short-term costs when their time on this earth is likely to be brief indeed (see Barker and Bearce, Reference Barker and Bearce2013). That is, although church attendance moderates the relationship between end times beliefs and preparedness, we suspect that this relationship has more to do with civic skill acquisition or intra-congregational discussion networks than it does the influence of elite communication (from Bakker and others). This should come as little surprise, as those who have resources are both more likely to prepare for disasters (e.g., Tierney et al., Reference Tierney, Lindell and Perry2001; see also Veil, Reference Veil2008) and to have opportunities to develop and practice civic skills in the context of a house of worship (Djupe and Grant, Reference Djupe and Grant2001).

As we suggest here, the context in which our study was conducted might have something to do with the degree to which apocalypticism and preparedness behaviors are linked among those who responded to our survey. Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, economic uncertainty, and political unrest, those who believe in the existence of an imminent apocalypse may have shifted from thinking in terms of “normal time” into “apocalyptic time” (see Gribben, Reference Gribben2009). And disasters—whether natural, economic, or political in extraction—have a way of encouraging people to prepare in any way they can for the next crisis.

Although we have no evidence that would bear on this particular mechanism, we have come to suspect that it is also possible that there has been a fundamental shift among those who believe in an impending apocalypse in terms of how they view the sequence of events that is likely to lead up to the end of the world. As Hummel (Reference Hummel2023) neatly documents, end times believers of all theological stripes now often anticipate that they will have to endure what Tim LaHaye—author of the Left Behind series—has termed the “humanist tribulation” (272; see also Gribben, Reference Gribben2009). That is, prior to the end of the world, believers in the “humanist tribulation” understand that they are likely to be pitted against an array of forces who control the levers of power in the United States—educational institutions, the mass media, and even the government itself—in a battle for the soul of the country. And in such a battle, it may seem prudent to keep a few canned goods and a little water at the ready, just in case.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048323000226.

Data

Upon publication, all data and code necessary to replicate the analyses in the paper will be made available through the authors’ dataverse page.

Competing interests

None.

Jason Adkins is an assistant professor of political science in the Department of History, Philosophy, Politics, Global Studies, and Legal Studies at Morehead State University where he researches politics, religion, and public administration in the United States and Europe.

Paul A. Djupe is a professor and director of Data for Political Research at Denison University, Granville, OH. He is the academic editor of the Temple University Press series Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics and is most recently the coauthor of The Full Armor of God: The Mobilization of Christian Nationalism in American Politics (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

Jacob R. Neiheisel is an associate professor of political science at the University at Buffalo, SUNY, where he is also affiliated with the Philosophy, Politics, and Economics (PPE) program. His current research focuses on apocalypticism in American politics.