Defining malnutrition and its prevalence

Protein energy malnutrition, referred to as malnutrition in this review, occurs when intake or uptake of energy and/or protein is lower than that required by the body for weight maintenance and physiological functioning. The delivery of sufficient energy and/or protein can be compromised by inadequate consumption, nutrient assimilation disorders, and higher energy and/or protein requirements influenced by the disease process, including inflammatory conditions within the body(Reference Cederholm, Jensen and Correia1).

Risk factors for malnutrition can be multi-faceted and include nutritional, functional, psychosocial, disease burden, age- and sex-related aetiologies. Poor appetite, hospitalisation, poor self-reported health and increasing age have recently been summarised from available literature as the strongest predictors of malnutrition(Reference Roberts, Collins and Rattray2). Older adults are at an increased risk of malnutrition owing to the physiological, functional and psychosocial changes that occur with ageing(Reference Cederholm, Jensen and Correia1,Reference de van der Schueren, Wijnhoven and Kruizenga3) . If left untreated, malnutrition leads to a progressive decline in overall health and reduced physical and cognitive function, eventually leading to longer hospital stays, increased likelihood of readmission to hospital, loss of independence, reduced quality of life and increased mortality(Reference Evans4,Reference Pryke and Lopez5) . These consequences also incur significant financial repercussions for the health care service, with the annual cost associated with malnutrition in Europe estimated to represent 2–10 % of health care budgets(Reference Rice and Normand6–Reference Elia9). With those aged 65 years and older estimated to account for 31⋅3 % of the European population in 2100, compared to 20⋅6 % in 2020(10), the burden of malnutrition is expected to rise considerably and requires a detection and prevention approach to its management.

Current estimates of malnutrition prevalence are inexact owing to heterogeneity in assessment criteria, screening tools and diagnostic criteria applied within prevalence studies, with as many as 48 screening tools in use(Reference Cederholm, Jensen and Correia1,Reference Power, de van der Schueren and Leij-Halfwerk11) . It is important to acknowledge the interchangeable terminologies used within prevalence studies so that ‘malnutrition risk’ and ‘malnourished’ are not always clearly differentiated and the quality of published studies is varied(Reference Power, de van der Schueren and Leij-Halfwerk11). Notwithstanding these challenges, it is accepted that there is considerable variation in malnutrition prevalence between settings with 5–10 % in older adults living at home, 20 % living in residential care settings, 40 % in hospital care settings and 50 % in rehabilitation settings estimated to be malnourished(Reference Kaiser, Bauer and Rämsch12). European estimates indicate the number of individuals at risk of malnutrition in the community is 8⋅5 %(Reference Leij-Halfwerk, Verwijs and van Houdt13) and international syntheses estimate 5⋅8 %(Reference Kaiser, Bauer and Rämsch12).

Screening tools and diagnostic criteria

A recent review of prevalence studies of community-dwelling older adults, including residents of nursing homes and rehabilitation facilities, examined BMI <20 kg/m2, weight loss or a combination of both for the purposes of assessing malnutrition prevalence using uniform definitions(Reference Wolters, Volkert and Streicher14). For low BMI, the highest prevalence was reported from nursing home settings and among women in all settings, and BMI decreased with increasing age of the sample. The weight loss criterion showed no clear pattern of occurrence across settings. Combining criteria definitions resulted in the lowest prevalence, whereas identifying malnutrition risk using any of the criteria increased prevalence. The importance of using age-specific cut-offs for defining low BMI among older adults was highlighted by this work as the general cut-off of BMI <20 kg/m2 is likely to underestimate malnutrition risk(Reference Wolters, Volkert and Streicher14).

Studies using screening tools or diagnostic consensus criteria including the mini-nutritional assessment(Reference Guigoz and Vellas15), American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition/Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics(Reference White, Guenter and Jensen16) and European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism(Reference Cederholm, Barazzoni and Austin17) observe much higher prevalence of malnutrition compared to that reported by Wolters et al.(Reference Wolters, Volkert and Streicher14) using BMI, weight loss and decreased food intake(Reference Kaiser, Bauer and Rämsch12,Reference Sánchez-Rodríguez, Marco and Schott18) . The commonly used mini-nutritional assessment-short form integrates the assessment of food intake, weight loss, mobility, disease state, neuropsychological problems and BMI into one composite score, is specifically designed for use in older adults and is commonly used in practice(Reference Guigoz and Vellas19). The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition/Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics consensus criteria first expanded upon the role of the inflammatory response in malnutrition risk and recommends the assessment of the severity of the acute disease state, weight loss, change in food intake and the integration of a nutrition-focused physical examination for loss of fat and/or muscle mass, and presence of oedema(Reference White, Guenter and Jensen16). The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism consensus statement later incorporated aetiology-based malnutrition diagnoses to include disease-related malnutrition with and without inflammation as well as malnutrition without disease with underlying psychological, socioeconomic or hunger-related causes(Reference Cederholm, Barazzoni and Austin17).

The developments in aetiology-based malnutrition assessment criteria in the past decade have been welcome and international consensus was called for to enhance and standardise detection and reporting. The global leadership initiative on malnutrition (GLIM) published in 2019 delivered a global consensus for the diagnosis of malnutrition, which identified screening, using a validated malnutrition screening tool, as the first step in identification(Reference Cederholm, Jensen and Correia1). The GLIM specifies that both aetiological criteria (reduced food intake, assimilation issues and/or disease burden and inflammatory processes) and phenotypic criteria (weight loss over time, BMI and reduced muscle mass) be used to determine malnutrition risk status. Muscle wastage, an independent risk factor for frailty and loss of independence, is not quantified well in current malnutrition screening literature. The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism previously recommended the use of the mini-nutritional assessment for assessing malnutrition in older adults in all settings(Reference Kondrup, Allison and Elia20); however, this recommendation needs to be considered in light of the recent focus on aetiological factors. Research is required now to apply the proposed GLIM criteria in validation studies for malnutrition diagnosis in diverse settings, diagnoses, sex and age groups(Reference Keller, de van der Schueren and Jensen21). Published work is now emerging with studies examining validation in different populations(Reference Yin, Liu and Lin22–Reference Sanchez-Rodriguez, Locquet and Reginster26) and more developments are expected in the coming years.

Implementing screening for malnutrition in community settings

While GLIM delivered an essential consensus and roadmap for the identification and diagnosis of malnutrition, significant challenges exist in implementing widespread malnutrition screening in practice. In hospital settings, it is recommended that malnutrition should be screened for on a weekly basis(Reference Kondrup, Allison and Elia20). It is estimated in the UK that almost 25 % of patients admitted to hospital from home are at risk of malnutrition, indicating that community-based malnutrition screening is warranted(Reference Russell and Elia27). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends annual screening for malnutrition among community-dwelling older adults (>75 years) with a primary care healthcare provider or with their general practitioner (GP)(28). Primary care non-dietetic healthcare professionals (HCPs) that encounter older people at risk of malnutrition include GPs, community-based nurses, pharmacists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and speech and language therapists(Reference Douglas, McCarthy and McCotter29–Reference Browne, Kelly and Geraghty32). GPs, community nurses or pharmacists are often the first point of contact for patients or their families with nutritional or weight loss concerns(Reference Douglas, McCarthy and McCotter29,Reference Dominguez Castro, Reynolds and Kennelly31–Reference Winter, McNaughton and Nowson35) . There are opportunities, therefore, to implement systematic community-based screening for the identification of malnutrition risk and malnutrition for the purpose of early intervention and treatment.

Malnutrition awareness among healthcare professionals in primary care

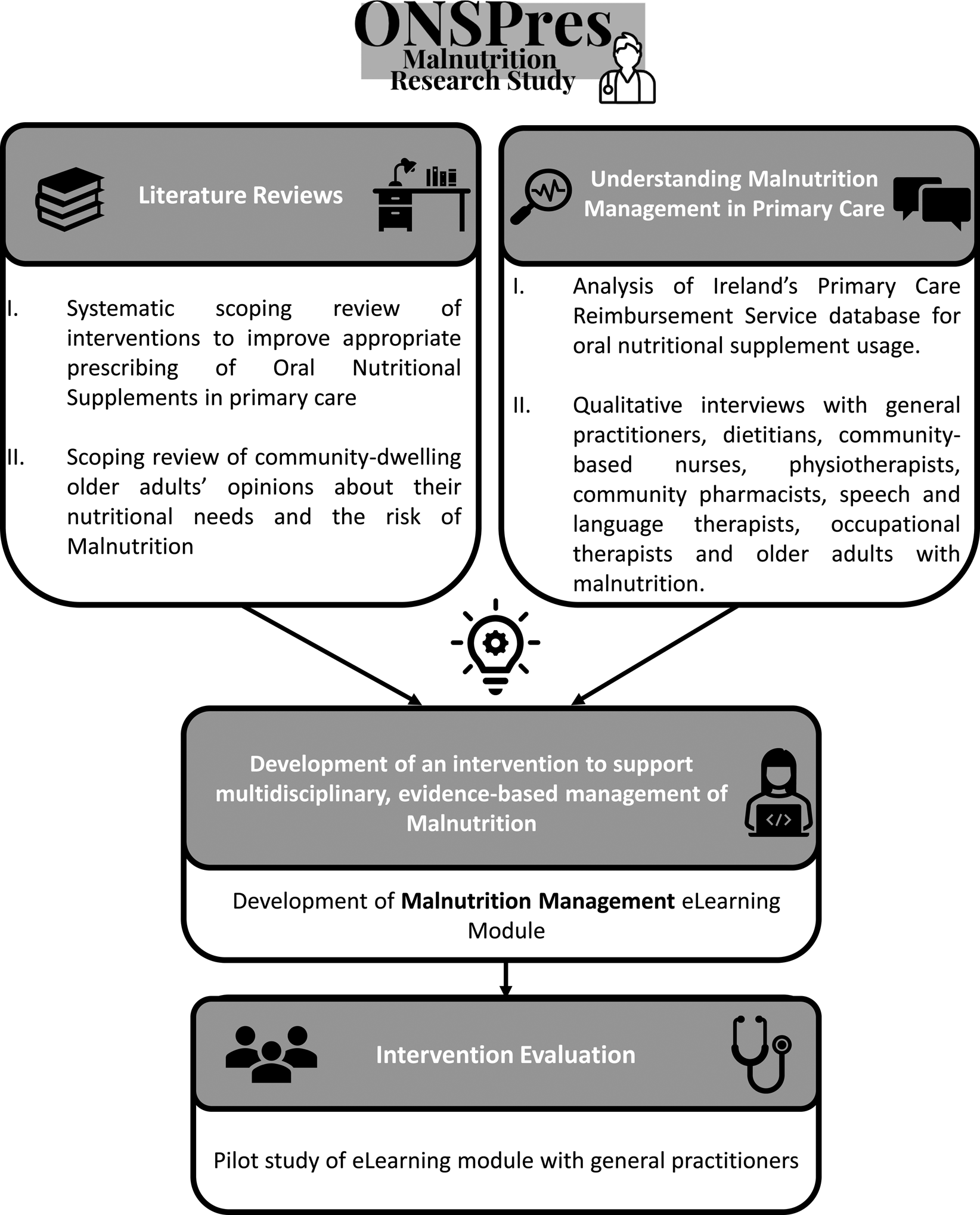

The oral nutritional supplement prescribing malnutrition research study (ONSPres study) addressed some key gaps in terms of identifying barriers to malnutrition identification, management and ONS prescribing in primary care in Ireland. Fig. 1 summarises the research undertaken within the ONSPres study from 2018 to 2021. The present paper will draw from the recent study, integrating learning from the wider literature and other jurisdictions.

Fig. 1. A summary of the work package flow within the ONSPres malnutrition research study between 2018 and 2021, investigating the barriers and facilitators of malnutrition screening and management among community-dwelling older adults.

Barriers to detecting malnutrition among community-dwelling older adults

Lack of awareness and knowledge

There is evidence to indicate that non-dietetic HCPs are not well-informed about malnutrition in community settings. In Ireland, GPs report poor understanding of malnutrition as a clinical condition and little background in nutrition education for treating the condition. GPs lack time and given their role in coordinating the often-complex healthcare needs of older patients, they do not currently prioritise malnutrition screening(Reference Dominguez Castro, Reynolds and Kennelly31). A lack of time and knowledge are common barriers in the literature(Reference Loane, Flanagan and Siún36–Reference Murphy, Mayor and Forde38). However, selecting the correct patient groups to screen, and remembering to screen are two factors that were also central in a cross-sectional survey of 493 GPs in France(Reference Gaboreau, Imbert and Jacquet39). GP responsibilities for managing multiple clinical conditions during a brief consultation must be acknowledged and it is understandable that a clinical screening tool which is not integrated into other assessments is forgotten or fails to be prioritised. In the ONSPres study, other non-dietetic HCPs, while aware of malnutrition, also reported a lack of competence in screening for and discussing malnutrition in practice(Reference Browne, Kelly and Geraghty32). One of the outcomes of poor malnutrition screening practices is the presentation of patients with more severe malnutrition; this was clearly highlighted by HCPs working in community care in Ireland(Reference Browne, Kelly and Geraghty32). Patients with a malnutrition diagnosis have reported that weight loss was first noticed by themselves, a carer or family member(Reference Reynolds, Dominguez Castro and Geraghty40); however, their awareness about the clinical condition and understanding of nutrition interventions needed is poor(Reference Reynolds, Dominguez Castro and Geraghty40–Reference Geraghty, Browne and Reynolds43). It is unknown how long older adults live with undetected weight loss and malnutrition, and HCPs believe that until functional limitations associated with weight loss or frailty are apparent, older adults will not seek support(Reference Browne, Kelly and Geraghty32). There is certainly evidence to support this, and carers can be more concerned about weight loss as a sign of something wrong than patients themselves(Reference Reynolds, Dominguez Castro and Geraghty40,Reference Avgerinou, Bhanu and Walters41) . Recent reviews have highlighted that older adults do not always associate poor appetite or weight loss with poor health, and may dislike being screened for malnutrition or being asked about dietary behaviours(Reference Harris, Payne and Morrison44,Reference Castro, Reynolds and Kennelly45) .

One novel and important finding from the ONSPres study, which has not been widely reported in the literature previously, is the stigma associated with the term ‘malnutrition’ among older adults(Reference Reynolds, Dominguez Castro and Geraghty40). Patients associated the term with famine, war, neglect, poverty and self-blame. Although non-dietetic HCPs are not confident in discussing malnutrition with patients, they reported being aware of the stigma and dietitians find alternative language in practice, focusing their communication with patients on weight loss and nutrients needs. While there is literature on stigma associated with many conditions such as obesity, mental health, cancer and epilepsy, there is little in the literature on health communications associated with malnutrition. These findings may be unique to Ireland, given our relatively recent history of famine, civil war and poverty, although it would be interesting to investigate if stigma exists elsewhere. It certainly indicates the need for public awareness campaigns about malnutrition and the potential to educate more widely on the benefits of screening among community-dwelling older adults.

Lack of resources in primary care

Resource limitations have been identified by HCPs as a barrier to identify and manage patients with malnutrition in Ireland and other countries(Reference Dominguez Castro, Reynolds and Kennelly31,Reference Browne, Kelly and Geraghty32,Reference Harris, Payne and Morrison44) . Where dietetic services are limited in primary care, GPs report prioritising other conditions such as obesity when referring to a dietitian(Reference Dominguez Castro, Reynolds and Kennelly31). Other HCPs including dietitians, speech and language therapists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, community nurses and community pharmacists highlighted the limitations of dietetic services in their primary care areas or lack of awareness about how to access dietetic services(Reference Browne, Kelly and Geraghty32). HCPs shared across a primary care network consisting of multiple primary care teams results in service limitations which is common in practise. This structure, with multiple locations, also presents communication challenges and difficulty accessing GPs(Reference Browne, Kelly and Geraghty32,Reference Bodenheimer, Ghorob and Willard-Grace46) . Primary care teams and networks are being prioritised in future models of health in Ireland(Reference Richard, Furler and Densley47,48) and GP participation in teams and networks is viewed as particularly important for effective teamworking and healthcare delivery(Reference Tierney, O'Sullivan and Hickey49). In Ireland, multiple working locations for HCPs mean that team members are not meeting in person, which can be a barrier to effective communication in primary care(Reference Bodenheimer, Ghorob and Willard-Grace46,Reference Oandasan, Gotlib Conn and Lingard50) . As the primary care model develops, it is important, therefore, to integrate malnutrition screening and care pathways in a sustainable way. One outcome of primary care service limitations is that the benefits of nutritional interventions initiated in tertiary settings can be lost upon discharge to the community(Reference Kaegi-Braun, Mueller and Schuetz51). Patients in the ONSPres study reported no contact with community dietitians after discharge from hospital and they were unable to convey a clear understanding of nutritional interventions in place(Reference Geraghty, Browne and Reynolds43). This is consistent with HCP accounts of insufficient resources to provide dietetic care for patients with malnutrition in the community(Reference Dominguez Castro, Reynolds and Kennelly31,Reference Browne, Kelly and Geraghty32) .

ONS prescribing

Although GPs are the key prescribers of ONS in Ireland, they report a lack of knowledge about the range available and how to select appropriate products for patients’ needs(Reference Dominguez Castro, Reynolds and Kennelly31). As described earlier, GPs do not routinely screen for malnutrition; therefore, ONS prescribing is not led by screening risk or evidence in most cases. GPs tend to continue approving ONS prescriptions initiated in hospital without monitoring for effectiveness and compliance(Reference Dominguez Castro, Reynolds and Kennelly31,Reference Browne, Kelly and Geraghty32) . Although ONS are a potentially effective intervention for malnutrition, there are greater benefits when dietitians are involved in selecting the appropriate product, providing patient-centred counselling on their use and monitoring older adults which include better adherence to recommendations, improved cost inefficiencies, as well as improved patient outcomes by reducing hospital readmission(Reference Freijer, Nuijten and Schols7,Reference Kennelly, Kennedy and Rughoobur52–Reference Liljeberg, Andersson and Blom Malmberg55) . In addition, patient-centred dietary counselling that accounts for the health, social and economic needs of the patient is an essential aspect of the nutrition care plan(Reference Cederholm, Jensen and Correia1,Reference Reinders, Volkert and de Groot56) .

Previous research has shown that social factors, such as living alone, limited shopping and cooking independence, contribute to long-term use of ONS among community-dwelling adults(Reference Kennelly, Kennedy and Rughoobur37). A recent analysis of ONS prescribing in Ireland found that older age, being female and polypharmacy were predictors of long-term use; however, younger age and central nervous system drugs were associated with greater volumes dispensed(Reference Dominguez Castro, Reynolds and Bizzaro57). Social factors associated with malnutrition and ONS usage include living alone, limited shopping and/or cooking independence, frailty, drug addiction and poor social support(Reference Kennelly, Kennedy and Rughoobur37,Reference Kennelly, Kennedy and Rughoobur52,Reference Gall, Harmer and Wanstall58) . The difficulty with prescribing ONS in isolation without further nutritional assessment is that underlying social factors are not addressed. The multidisciplinary team involved in older adult care in the community, however, is well placed to identify solutions to social issues that are contributing to malnutrition once they are identified. This type of information has been shared in previous education interventions in primary care and improves knowledge and awareness among HCPs(Reference Kennelly, Kennedy and Rughoobur52).

A finding from the ONSPres study that has not been widely reported is the potential conflict of interest arising from dietitians working with commercial ONS companies assessing patients in private nursing home facilities(Reference Browne, Kelly and Geraghty32). This service may be unique to the Irish setting, although industry representatives are active in ONS promotion among HCPs in most healthcare settings. In 2010, an Irish study reported that ‘visits from sales representatives’ were a common source of malnutrition information for GPs and community-based nurses(Reference Kennelly, Kennedy and Rughoobur52). Some GPs and HCPs view commercial input as a barrier to prescribing ONS based on the potentially biased source of the recommendation(Reference Dominguez Castro, Reynolds and Kennelly31,Reference Browne, Kelly and Geraghty32) ; therefore, it is important that unbiased education, training and continuous professional development on malnutrition are available to all HCPs working with older adults.

Interventions and solutions

A successful malnutrition education programme with community-based HCPs in Ireland was demonstrated by Kennelly et al., whereby public health nurses, primary care practices (GPs and practice nurses) and private nursing homes (staff nurses) in one county took part in malnutrition screening and management education led by community dietitians(Reference Kennelly, Kennedy and Rughoobur52). Malnutrition screening and knowledge improved after education and training, and most HCPs had implemented and were confident in using the malnutrition universal screening tool(Reference Elia59) and providing first-line dietary advice at 6 months follow-up(Reference Kennelly, Kennedy and Rughoobur52). Despite the strong evidence base to support malnutrition screening and care pathways(Reference Cederholm, Jensen and Correia1), there has been a lack of development in implementing screening more widely in primary care. It is well documented that nutrition is under-developed in medical education programmes(Reference Crowley, Ball and Hiddink60), despite documented interest and will from students and medical professionals(Reference Mogre, Stevens and Aryee61,Reference Mogre, Stevens and Aryee62) .

Online learning can improve accessibility to continuous professional development training for HCPs and may be an efficacious route to widespread malnutrition screening and management education. Literature reviews(Reference Castro, Reynolds and Kennelly45,Reference Cadogan, Dharamshi and Fitzgerald54) and findings from the ONSPres study were used to design an e-learning module that was recently evaluated by 31 GPs in Ireland(Reference Geraghty, Castro and Reynolds63). The interactive e-learning module was approximately 60–90 min in duration and, as well as malnutrition education and providing resources, the content included case-based examples to teach the application of screening tools. Case studies required participants to calculate weight loss, malnutrition risk scores and approaches to treatment and follow-up. The online module was well received by GPs and knowledge and case-based practice improved from baseline immediately and 6 weeks after training(Reference Geraghty, Castro and Reynolds63). GPs were chosen for participation in the e-learning module pilot study as they are licensed prescribers of ONS in Ireland; however, there are plans to make the module available to other HCPs working with older adults in primary care.

Professional education and learning will improve knowledge, awareness and ideally increase screening for malnutrition among HCPs. However, this will not address the resource barriers to malnutrition management that have been outlined. When older adults are screened regularly, care pathways that include dietetic referral systems for full nutritional assessment are required in primary care. Older adults at ‘low risk’ or ‘moderate risk’ of malnutrition, with uncomplicated healthcare needs, can often be managed without direct dietetic care and resources, including a malnutrition support toolkit, that are widely available via the health service to assist HCPs in providing first-line advice.

Conclusions

This review highlights the developments in assessment and screening for malnutrition over the past decade. Future work will focus on validating malnutrition diagnostic tools using the GLIM criteria. The barriers to identifying and treating malnutrition among older adults in primary care are described. The solutions to address knowledge and awareness deficits among HCPs and community-dwelling older adults are multi-pronged and include education and training for HCPs and public awareness campaigns aimed at older adults themselves and their carers. Resource deficits will require firm commitments from health services to prioritise the timely identification of malnutrition among our ageing populations and effective communication structures within primary care. Finally, investment in community nutrition and dietetics services for older adults will enhance nutrition skills within the multidisciplinary team in primary care and ensure the sustainability of evidence-based care pathways for malnutrition identification and management.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Health Research Board (HRB) for funding the ONSPres Study. The HRB supports excellent research that improves people's health, patient care and health service delivery. The HRB aims to ensure that new knowledge is created and then used in policy and practice. In doing so, the HRB supports health system innovation and creates new enterprise opportunities. The authors wish to acknowledge participants within the ONSPres study, study partners and collaborators and the wider research team, including post-doctoral researchers Dr Patricia Dominguez-Castro and Dr Ciara Reynolds.

Financial Support

This work was supported by a grant from the Health Research Board in Ireland (grant number: RCQPS-2017-4).

Conflict of Interest

None.

Authorship

The authors had sole responsibility for all aspects of preparation of this paper.