On a cold January morning in early 2017, Syrian government officials and rebel leaders met face to face in Astana, Kazakhstan, to negotiate an end to a conflict that, to that point, had lasted more than five years and cost more than 450,000 lives (Barnard and Saad Reference Barnard and Saad2017; Human Rights Watch 2017). Within hours, the talks fell apart—one of many instances of failed negotiations to end this conflict. The sheer number and variety of domestic and international actors involved in the Syrian conflict and the subsequent strategic challenges to ending it reflect several core international relations (IR) concepts, from bargaining theory and international law to domestic politics and human rights.

These concepts can be difficult to convey to college students who are new to the field in a way that is engaging, informative, and not overwhelming. Large introductory courses typically are populated by students new to the discipline who may struggle to connect theoretical approaches to real-world international affairs (Arnold Reference Arnold2015; Loggins Reference Loggins2009). A growing literature suggests that active-learning techniques, including in-class simulations, improve students’ experiential understanding of IR theories, maintain their level of interest, and encourage information retention (Asal and Blake Reference Asal and Blake2006; Baranowski and Weir Reference Baranowski and Weir2015; Jones and Bursens Reference Jones and Bursens2015; Krain and Lantis Reference Krain and Lantis2006; Morgan Reference Morgan2003). However, using such active-learning methods involves tradeoffs and requires careful linking of simulation design to course material (Wedig Reference Wedig2010).

This article describes an extended classroom simulation of the Syrian conflict that culminates in a simulated peace conference and systematically links 11 weeks of lectures, reading material (Frieden, Lake, and Schultz Reference Frieden, Lake and Schultz2016), and student assessment to this complex conflict. We outline the costs and benefits of different simulation designs to encourage students’ understanding of IR concepts, and we propose a course plan for tight cohesion among course material, assessment, and a simulation—regardless of class size.

The article first describes the simulation design and several important decisions behind it. Subsequent sections demonstrate how lectures and reading material were linked to simulation activities in teaching core concepts (i.e., domestic politics, non-state actors, and bargaining interactions), as well as the importance of reflective analysis and an integrated learning plan. We conclude by summarizing our main contributions and how the simulation can be adapted to other teaching scenarios.

This article describes an extended classroom simulation of the Syrian conflict that culminates in a simulated peace conference and systematically links 11 weeks of lectures, reading material (Frieden, Lake, and Schultz Reference Frieden, Lake and Schultz2016), and student assessment to this complex conflict.

SIMULATION DESIGN

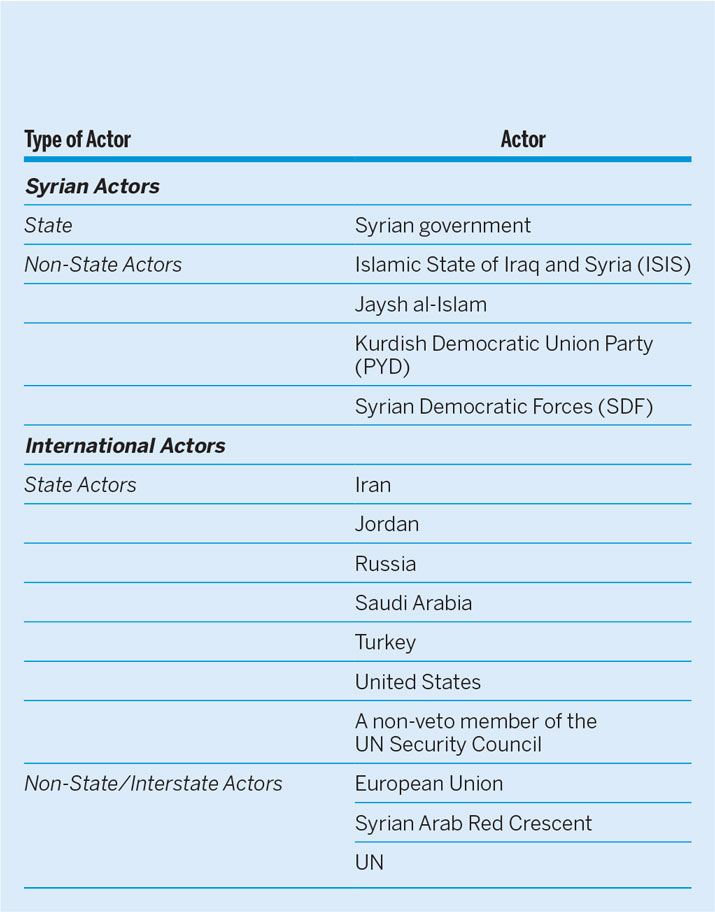

The simulation was designed for a 550-person “Introduction to International Relations” course at the Australian National University and took place during weekly 15-student sections. To date, it has been used twice, in 2017 and 2018. Each section, facilitated by a teaching assistant (TA), operates a discrete simulation that runs over 11 weeks and culminates in two weeks of multi-stakeholder negotiations. During the first week, students are randomly assigned a real-world actor with an interest in the Syrian conflict from among three actor types: states, non-state actors, and international actors (table 1).

Table 1 Simulation Roles

Four distinct issue areas (i.e., humanitarian aid, economic sanctions, ceasefire, and political transition) are discussed throughout the simulation and negotiated in a two-week simulated summit. To ensure consistent teaching across sections, the instructor provides a weekly substantive and logistical TA guide (see the online appendix), as well as regular in-person meetings throughout the semester.

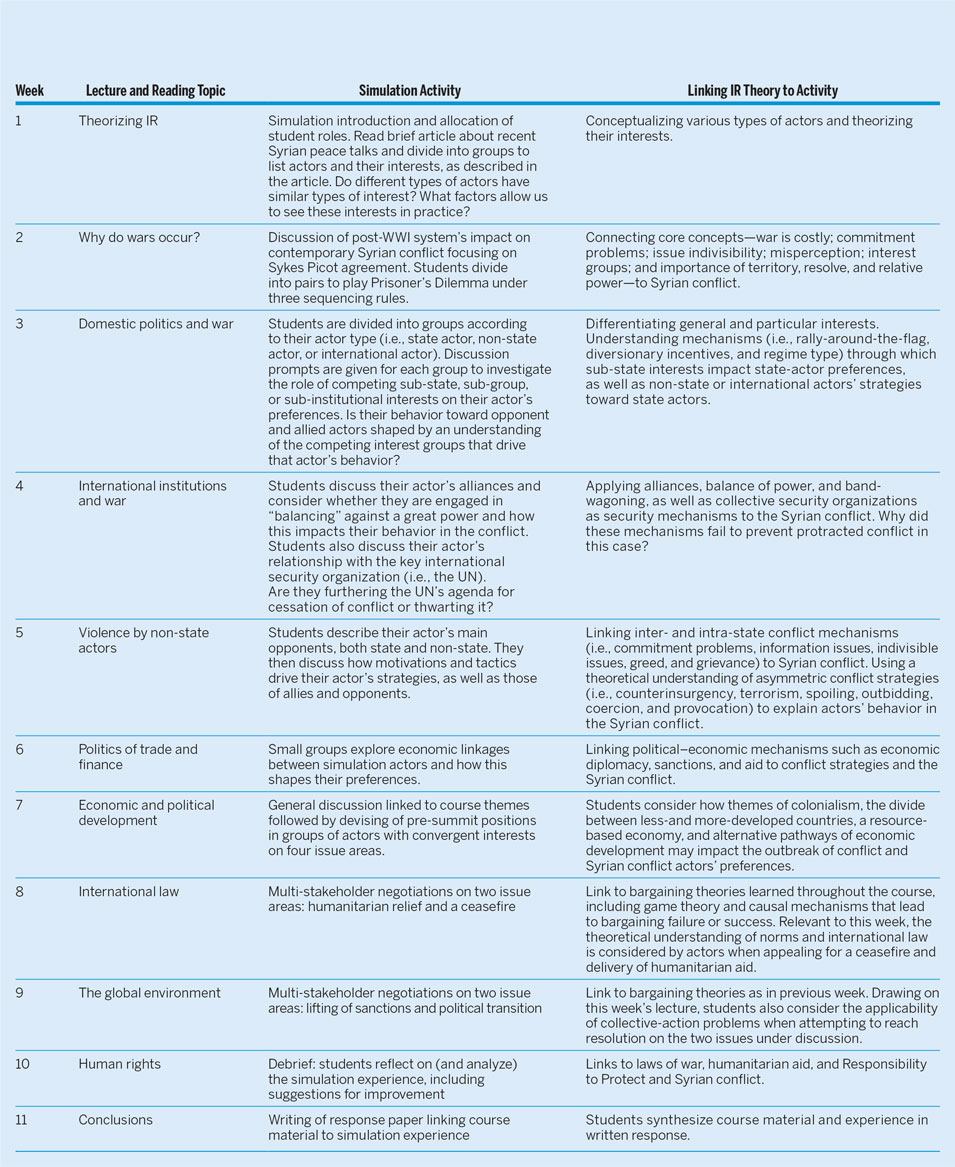

The simulation is divided into three phases (table 2). In the first phase, students are briefed on the simulation, assigned an actor, and guided through activities to facilitate student comprehension of weekly course material through the lens of their assigned actor. In the second phase, using bargaining frameworks learned in the course, students engage in multi-stakeholder negotiations spanning the four issue areas. In the final phase, they discuss the simulation and lessons learned.

Table 2 Simulation Outline

We chose the Syrian conflict because of its normative, policy-making, and theoretical importance, as well as its complexity and conceptual richness. As of this writing, the Syrian conflict has resulted in more than 450,000 deaths and millions of displaced persons, affected regional interactions, and escalated Russian–US tensions. It comprises overlapping conflicts involving the Syrian government; diverse rebel groups; and state actors including Turkey, Iran, the United States, and Russia, as well as civilian and international groups including the Syrian Arab Red Crescent, the United Nations (UN) Security Council, and others.

Designing a simulation requires choosing either a real or a hypothetical case. A real-world, ongoing case such as the Syrian conflict encourages student interest and engagement (Austin, McDowell, and Sacko Reference Austin, McDowell and Sacko2006, 89–90) by demonstrating the applicability of IR concepts to a political conflict reported on the nightly news. However, it also might trigger students who are personally affected by the conflict, or a student allocated a violent actor may be uncomfortable being associated with this actor. A real conflict also may detract from course engagement if students become absorbed in current events rather than in how IR theories apply to those events. These disadvantages can be mitigated by introducing the case to students as—first and foremost—an analytical arena to apply course theories to current policy making. This can create analytical and reflective distance between students and their actor. In addition, students should be made aware of points of contact (i.e., instructor, TA, or college support services) if they feel any discomfort with the simulation.

A second choice is whether to run a short or long simulation; the latter is expected to provide greater educational benefit (Glazier Reference Glazier2011, 376). However, due in part to logistical limitations (Nishikawa and Jaeger Reference Nishikawa and Jaeger2011, 135–36), many simulations are short running. Baranowski and Weir’s (Reference Baranowski and Weir2015) survey of 27 course-based simulations found that only six were semester-long. The main disadvantage of a long-running simulation is the tradeoff between time spent on exploring the simulation case in depth and time covering multiple case studies and examples. Teachers “sacrifice a degree of breadth” in favor of depth (Smith and Boyer Reference Smith and Boyer1996, 691); however, discussion of multiple, complex real-world examples may be less useful to first-year college students with a limited understanding of these events (Arnold Reference Arnold2015, 162). Instead, as students grapple with new material, a simulation can provide a framework within which they accumulate a deeper comprehension of one case study, understanding new concepts through the lens of their actor. In our case, a long-running simulation was best suited to our introductory IR course.

LINKING THEORIES TO PRACTICE

A simulation is a useful teaching tool to the extent that it helps students engage with and understand course substance. There are many ways to teach an introductory IR class, focusing on historical events or particular theoretical paradigms. Our simulation is part of a coherent puzzle-based approach to understanding why scholars study different parts of IR and the assumptions and implications underlying the theoretical frameworks they build to solve these puzzles. Lectures complement the reading material; each week poses simple questions (e.g., Why is there war? How can domestic factors explain international relations?) that also can be connected to the Syrian conflict. As table 2 demonstrates, the topics follow in a logical sequence that builds on previous weeks’ material. Two examples highlight the links among the lectures, readings, and simulation.

Domestic Politics and the Syrian Conflict

The Week 4 lecture introduces students to the causal mechanisms by which domestic politics can affect the likelihood of violent conflict. Core concepts introduced in the lecture and assigned reading (Frieden, Lake, and Schultz Reference Frieden, Lake and Schultz2016, ch. 4) include mechanisms through which domestic interest groups affect state policy, the “rally-around-the-flag” effect, diversionary incentives for actors to engage in violent conflict, and how regime type determines a state’s selectorate and affects its decision-making calculus.

The applicability of these concepts to the Syrian conflict is illustrated by the impact of domestic interests driving states including Iran, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Russia and the US level of engagement in Syria. For example, Russia’s intervention in Syria may be driven by domestic interests to divert attention away from the costs of international sanctions after the invasion of Crimea. The reticence of the United States to intervene in Syria is partly driven by domestic electoral concerns and a growing resistance to US “boots on the ground” in the Middle East. In addition to state actors, the concepts outlined can apply to non-state actors and international actors whose strategic calculus is impacted by the domestic political calculus of both their allies and their opponents in the conflict.

In the Week 4 section, students consider how domestic interests affect their actor’s strategies and behavior. First, they discuss whether their actor’s preferences are cohesive or fractured by competing interest groups. Second, they examine how domestic politics can shape alliances or rivalries in an internationalized civil conflict.

Non-State Actors and the Syrian Conflict

Week 6 examines causal mechanisms behind asymmetric conflicts involving non-state actors. Lectures and assigned readings (Frieden, Lake, and Schultz Reference Frieden, Lake and Schultz2016, ch. 6) focus on how civil war can be seen as a bargaining failure resulting from incomplete information, commitment problems, and indivisible issues. We examine group-, country-, and international-level factors that could account for the outbreak of civil war. We also discuss counterinsurgency strategies and terrorism as a tactic employed by non-state actors. We note the four key terrorist strategies of coercion, provocation, spoiling, and outbidding used to achieve political goals.

We can examine causes at the group level (e.g., sectarian divisions), country level (e.g., authoritarian regime type), and international level (e.g., Arab Uprisings and NATO’s 2011 intervention in Libya), as well as incomplete information (e.g., both the Assad regime and rebel groups may have overestimated their ability to win the conflict), commitment problems (e.g., lack of mechanisms to enforce agreements), and indivisible issues (e.g., leadership of Syria).

In the Syrian conflict, these concepts can frame our understanding of the underlying causes. We can examine causes at the group level (e.g., sectarian divisions), country level (e.g., authoritarian regime type), and international level (e.g., Arab Uprisings and NATO’s 2011 intervention in Libya), as well as incomplete information (e.g., both the Assad regime and rebel groups may have overestimated their ability to win the conflict), commitment problems (e.g., lack of mechanisms to enforce agreements), and indivisible issues (e.g., leadership of Syria). In addition, tactics used by ISIS, the Kurdish Peshmerga forces, and the Syrian Democratic Forces can be categorized theoretically according to the four types of terrorist strategies introduced to students.

In sections, students consider who is an ally and who is an opponent for their allocated actor. Based on this information, the TA draws a conflict matrix that shows clusters of groups that share at least one key ally or opponent. These cluster groupings then discuss whether incomplete information, commitment problems, or indivisible issues form the greatest obstacle to resolving the divergence of interest with their opponent. Next, the groups examine the type of counterinsurgency and terrorism tactics used by themselves and/or their opponents as well as the function of these strategies in impacting their actor’s strategic calculus in achieving their objectives in the conflict.

These examples of domestic politics and non-state violent actors illustrate how a simulation can be designed to link readings, lectures, and simulation activities. To complement this process and link learning outcomes with a written assessment, students complete two short written pieces, one in Week 4 and one in the week preceding the multi-stakeholder negotiations. First, they post a 300-word description of their actor to their section’s online forum, accessible only to students in their section. Second, they write a 300-word position paper (also posted to the section forum) the week before negotiations begin, in which they outline their actor’s interests regarding the four issue areas. Students are encouraged to read the profiles and position papers of other actors. They are given time to negotiate initial alliances in section, as well as to participate in online discussions in the forum and coordinate outside of class in person or online.

SIMULATED CONFERENCE

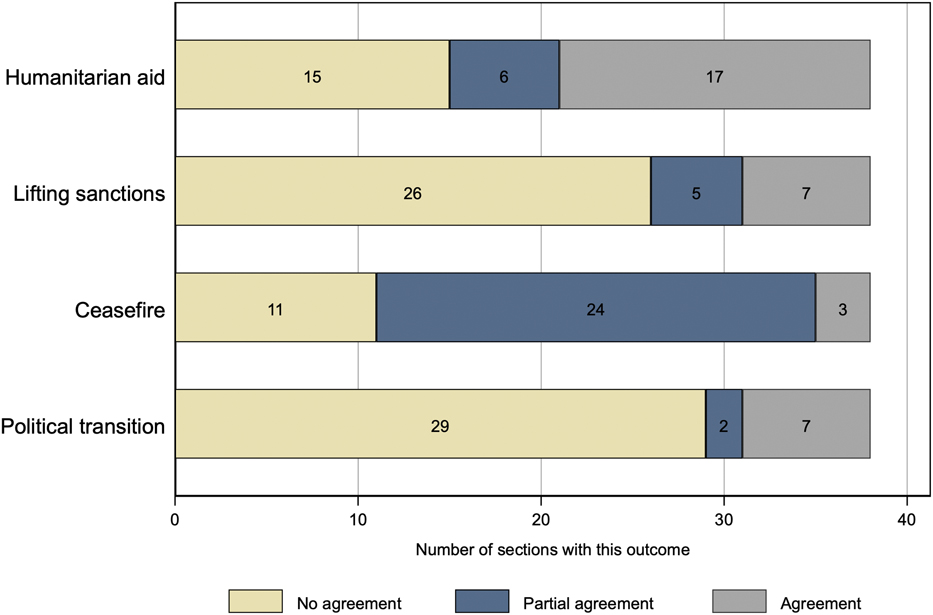

These substantive sections provide the foundation for two weeks of sections devoted to a simulated conference modeled after real cases such as the 2017 Kazakhstan conference. The first session focuses on two issue areas: humanitarian-aid provision and a temporary ceasefire to enable aid deliveries. The second section focuses on ending Syrian economic sanctions and longer-term solutions to the conflict, including a leadership transition. Each week ends with a joint communiqué written by the TA during discussion and posted online. Figure 1 shows the 2018 simulation outcomes.

Figure 1 Simulation Outcomes, 2018

First-year IR students are frequently introduced to the concept of international bargaining interactions. In a long-running simulation, we suggest dedicating two or three pivotal sessions to facilitating student understanding of bargaining theory through simulated negotiations with other actors. Students are primed before starting their negotiation sessions to pay attention to how actors’ strategies and interactions in negotiations can be framed in terms of core IR concepts related to the bargaining frameworks taught in class.

Concepts linked to bargaining that are covered in lectures and readings include causal mechanisms such as coercive bargaining, issue linkage, tying hands, brinkmanship, deterrence, and the impact of a limited bargaining range or outside options. In addition, Fearon’s (Reference Fearon1995) framework for explaining why bargaining fails (i.e., commitment problems, information problems, and indivisible issues) also is emphasized and is particularly useful for the simulation. Students consider whether these factors help in understanding the success or failure of negotiations in each issue area. Finally, formal models like the Prisoner’s Dilemma (i.e., introduced in Week 3 with students playing the game in sections) also provide a framework for explaining negotiation outcomes.

STUDENT REFLECTION

Previous research suggests that analysis and reflection of experience increases learning integration (Glazier Reference Glazier2011, 380). In our simulation, we include two modes of reflection: an in-person group debrief and an individually written response paper. The former allows students to reflect critically and interactively on their experience (facilitated by an instructor or TA) and provides a “wealth of potentially useful information to instructors” (Baranowski and Weir Reference Baranowski and Weir2015, 395) to improve future iterations of the simulation.

As a further means of integrating the simulation with course material and assessment, after the conference concludes, students write a 1,000-word response paper in which they critically reflect on their simulation experience and link the entire simulation (with a particular focus on the two weeks of negotiations) to the theoretical IR concepts introduced throughout the course. This not only provides an additional incentive for in-depth student engagement with the simulation; it also is a means for integrating lessons learned from the simulation.

CONCLUSION

Engaging first-year undergraduate students with IR concepts and theories is often a challenging task. Using a contemporary, applied lens can be a useful means to learn about and grasp complex theoretical concepts. Similar to the failed 2017 conference in Astana, Kazakhstan, diplomatic efforts must address actors’ interests and what the international community can reasonably support.

This article describes an extended simulation and a discussion of the Syrian conflict as part of an introduction to international relations course. It highlights the connections between IR theories (e.g., bargaining, domestic politics, and violence by non-state actors) to the current Syrian conflict. It also suggests ways that this simulation can help students in a large class feel more directly connected to the theoretical material and lectures.

This simulation can be adapted in a number of ways. Given that each section constituted a discrete simulation with 15 actors, the simulation could be used in a smaller class of 15 students. In a class of 30 to 50 students, two or three students could be assigned the same role and work as a group, or students could be allocated various actors within a role (e.g., actors representing the executive, bureaucracy, and/or interest groups). If a full-semester simulation is not practical, the simulation can be shortened to two to three weeks, with one week dedicated to choosing roles and discussing their motivations and structural constraints and a one- to two-week conference focusing on one to four of the negotiation topics. Last, it is possible to choose a different conflict of more interest to the instructor or students. For instance, current conflicts in Yemen, Myanmar, Nigeria, South Sudan, and Cameroon also provide material for good discussions of IR theories and international interests.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519000556

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tristan Dimmock and Jana von Stein for their help in designing and implementing this simulation. We also thank the anonymous reviewers and editor for their helpful comments and suggestions. This simulation was made possible in part by a 2017 Australian National University Teaching Enhancement Grant.