Fuelled by recent inquiries into the apparent failure of psychiatric care (Department of Health and Social Security, 1988; Reference RitchieRitchie, 1994) and sensational media reports, society's view of schizophrenia is largely negative. Although the Royal College of Psychiatrists (‘Every Family in the Land: Recommendations for the Implementation of a Five-year Strategy: 1998-2003’; available upon request from the External Affairs and Information Services Department, The Royal College of Psychiatrists, 17 Belgrave Square, London SW1X 8PG) and World Health Organization (Reference SartoriusSartorius, 1997) have launched campaigns to reduce the stigma of mental illness, psychiatrists themselves have been implicated in contributing to misunderstandings about schizophrenia by withholding information from their patients (Svensson & Hanson, 1994; Reference Leavey, King and ColeLeavey et al, 1997), giving them confusing information (Reference Main, Gerace and CamilleriMain et al, 1993; Reference Barker, Shergill and HigginsonBarker et al, 1996) and of being reluctant to tell them their diagnosis (Reference McDonald-Scott, Machizawa and SatohMcDonald-Scott et al, 1992; Reference Luderer and BockerLuderer & Bocker, 1993).

The study

All consultant psychiatrists working in Scotland in May 1997 (n=323; from a database supplied by the information and statistics division of the NHS in Scotland) were sent a questionnaire asking their opinion and practice on telling psychiatric patients their diagnosis (copies available from authors upon request). Ninety-five per cent confidence intervals (95% CIs) for proportions and their differences were calculated.

Findings

Response rate

Two hundred and forty-six questionnaires were returned (76% response rate). Thirty-five were excluded from analysis: 25 respondents stated the topic was not relevant to their speciality, five were not practicing in clinical psychiatry, four questionnaires were spoiled and one respondent no longer worked in Scotland.

Characteristics of the respondents

We achieved a 76% response rate. Seventy-seven (36%; 95% CI 30-43%) were women. One hundred and four (49%; 95% CI 42-56%) had been consultants for over 10 years. Women were a smaller proportion of the latter group — 24% compared with 49% of those with 10 years' experience or less (a difference of 25%; 95% CI 12-37%).

Telling the diagnosis to different diagnostic groups

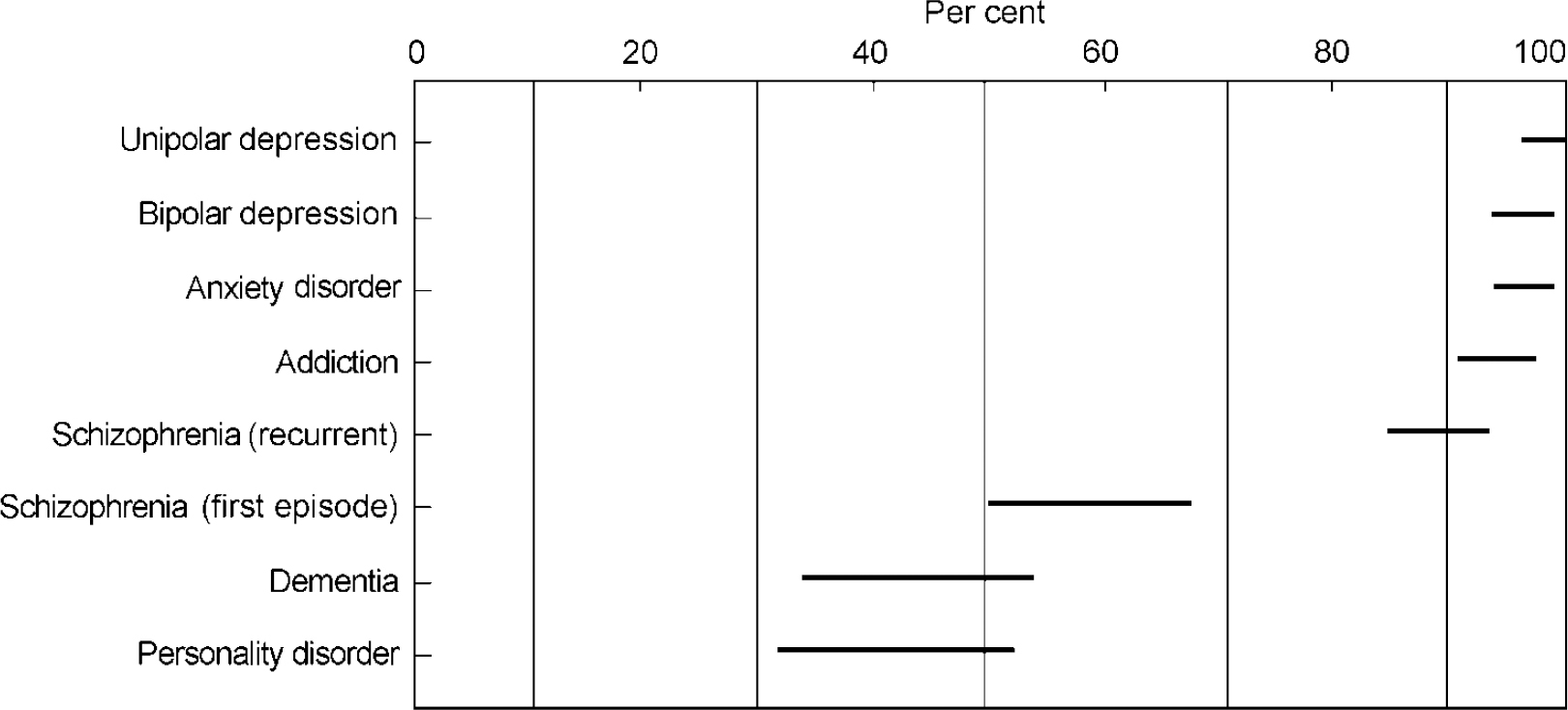

Consultants were asked if it was their normal clinical practice to inform patients who met standard diagnostic criteria of their exact diagnosis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Percentage of consultants who would tell patients their exact diagnosis (Confidence Intervals).

The highest positive response was for unipolar depression (207; 98%; 95% CI 96-100%), followed closely by bipolar disorder, anxiety disorder and alcohol or drug misuse. In cases where the diagnosis of schizophrenia was not in doubt, 187 (89%; 95% CI 84-93%) would tell the diagnosis in a recurrent episode; 124 (59%; 95% CI 52-65%) would tell the diagnosis in a first episode. A minority would tell a diagnosis of dementia or personality disorder — 92 (44%; 95% CI 37-50%) and 88 (42%; 95% CI 35-48%), respectively.

Telling patients they have schizophrenia

A variety of terms were used (Table 1). Two hundred (95%; 95% CI 9-98%) thought a consultant psychiatrist, perhaps with other staff, would be the best person to give the diagnosis. Various approaches were reported: 157 (74%; 95% CI 69-80%) would give the diagnosis as part of a routine consultation and 63 (30%; 95% CI 24-36%) would arrange a separate appointment, with 189 (90%; 95% CI 85-94%) meeting relatives if the patient consented. Most would give information about voluntary organisations (171; 81%; 95% CI 76-86%); 103 (49%; 95% CI 42-56%) gave written information; 84 (40%; 95% CI 33-46%) recommended books and 76 (36%; 95% CI 30-43%) referred the patient to an education group run by local psychiatric services. Only 108 (51%; 95% CI 44-58%) would volunteer the diagnosis without being asked. A variety of comments and experiences were reported (Table 2).

Table 1. Terms used when telling a patient their diagnosis of schizophrenia

| Terms | Number | Percentage | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | 180 | 85.0 | 80 to 91 |

| Psychosis/psychotic illness | 148 | 70.0 | 63 to 78 |

| Major mental illness/mental illness | 108 | 51.0 | 42 to 61 |

| Mental breakdown | 40 | 19.0 | 7 to 31 |

| Paranoid psychosis | 3 | 1.0 | -12 to 15 |

| Serious nervous illness | 3 | 1.0 | -12 to 15 |

| Serious mental illness | 2 | 1.0 | -13 to 14 |

| Major psychiatric illness | 1 | 0.5 | -13 to 14 |

| Schizoaffective illness | 1 | 0.5 | -13 to 14 |

| Sickness of the mind | 1 | 0.5 | -13 to 14 |

| Insanity | 1 | 0.5 | -13 to 14 |

| Loss of touch with reality | 1 | 0.5 | -13 to 14 |

| Serious disorder | 1 | 0.5 | -13 to 14 |

| Chemical imbalance in the brain | 1 | 0.5 | -13 to 14 |

Table 2. Experience of telling patients their diagnosis of schizophrenia

| Statement | Number who agree with statement | Percentage | 95% I |

|---|---|---|---|

| Most patients have guessed before I tell them | 122 | 58 | 49 to 67 |

| Most patients cannot understand the term schizophrenia | 121 | 57 | 49 to 66 |

| It makes me feel uncomfortable to tell patients their diagnosis | 90 | 43 | 32 to 53 |

| Most patients don't want to know their diagnosis | 28 | 13 | 1 to 26 |

| Telling often worsens the doctor—patient relationship | 21 | 10 | -3 to 23 |

| I don't have adequate time to tell patients their diagnosis | 188 | 9 | -4 to 21 |

| Telling may worsen the prognosis | 11 | 5 | -8 to 18 |

| Telling often worsens the mental state | 6 | 3 | -11 to 16 |

Differences between groups of respondents

A higher proportion of women consultants volunteered the diagnosis of schizophrenia without being asked (56% v. 46%; 49% CI for the difference: 5-23%), referred the patient to self-help groups (88% v. 77%; 95% CI for the difference: 1-22%) and met with relatives to discuss the diagnosis (94% v. 87%; 95% CI for the difference: 2-4%).

Consultants in post for more than 10 years were more likely to feel uncomfortable telling the diagnosis of schizophrenia (47% v. 38%, a difference of 9%; 95% CI 5-22%) and were less likely to volunteer the diagnosis without being asked (42% v. 60%, a difference of 18%; 95% CI 14-31%).

Open text comments

A number of enlightening comments were received and the following list records some common themes:

-

(a) “I give patients my formulation and don't normally give a diagnosis.”

-

(b) “… Experience of people with schizophrenia who commit suicide would suggest that insight is a factor in a number of cases. This emphasises the potentially devastating effect of knowledge of diagnosis and the importance of handling the information with extreme care and support.”

-

(c) “… I am impressed by the number of people with schizophrenia who I meet who do not know their diagnosis and the largely positive effects telling the diagnosis has.”

-

(d) “The most important thing in giving the diagnosis is to try to ensure they are ready to receive it and that they want to know the details.”

-

(e) “Knowledge of the diagnosis allows information and education on the subject.”

-

(f) “My problem is that I don't believe schizophrenia exists — even though there's a lot of it about.”

-

(g) “I don't know what standard diagnostic criteria are, but I know a schizophrenic when I've interviewed the relatives and he walks through the door.”

-

(h) “The consequences of schizophrenia in terms of social adaptation and symptoms cannot be hidden.”

Discussion

Doctors have a duty to give patients information in a way that is understandable to them (General Medical Council, 1998). They must decide how much information to give and how and when to give it, but not avoid the issue or presume patients do not want to know (Reference Pendleton and HaslerPendleton & Hasler, 1983). Avoiding discussion of diagnosis may only heighten patients' anxieties (Reference Carstairs, Early and RollinCarstairs et al, 1985).

Giving patients with schizophrenia information about their illness is recommended in good practice statements (CRAG-SCOTMEG Working Group on Mental Illness, 1995) and clinical guidelines (American Psychiatric Association, 1997; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 1998). Informed patients may enjoy many potential benefits: better engagement with services (Reference Foulks, Persons and MerkelFoulks et al, 1986; Reference BebbingtonBebbington, 1995); improved knowledge (Reference Smith, Birchwood and HaddrellSmith et al, 1992); higher quality of life (Reference Atkinson, Coia and GilmourAtkinson et al, 1996); and reduced negative symptoms (Reference Goldman and QuinnGoldman & Quinn, 1988). Uninformed patients may discover their diagnosis in a distressing way, such as on a form, at court or when accessing their records (Reference AtkinsonAtkinson, 1984). They may not access voluntary sector services or may give incorrect information in benefit claims or housing applications. They may not know their responsibility to notify the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency about their fitness to drive (DVLA, 1995).

There can be risks and difficulties in informing patients they have schizophrenia. The risk of suicide, thought to be highest early in the illness and associated with insight (Reference KingKing, 1994; Reference Amador, Freidman and KasapisAmador et al, 1996), must be assessed in each patient. Some psychiatrists do not use the diagnosis of schizophrenia even after the introduction of operationally defined criteria (World Health Organization, 1992; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), preferring their own idiosyncratic diagnostic system (Reference Saugstad and OdegardSaugstad & Odegard, 1983). There is some debate about the validity of making a diagnosis of schizophrenia (Reference Clafferty, McCabe and BrownClafferty et al, 2000; Reference FisherFisher, 2000; Reference KingKing, 2000), which is outside the remit of our study — we asked psychiatrists only about established illness where the diagnosis was not in doubt. Psychiatrists have been accused of using stigmatising labels (Reference LallyLally, 1989), but stigma arises from the symptoms and signs of the illness itself, not merely its name (Reference Penn, Guynan and DailyPenn et al, 1994).

Society's prejudice towards people with schizophrenia may improve with current education campaigns, but a change in psychiatric practice may also be necessary. When psychiatrists are willing to break free from the conspiracy of silence surrounding schizophrenia, the public may follow their example.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.