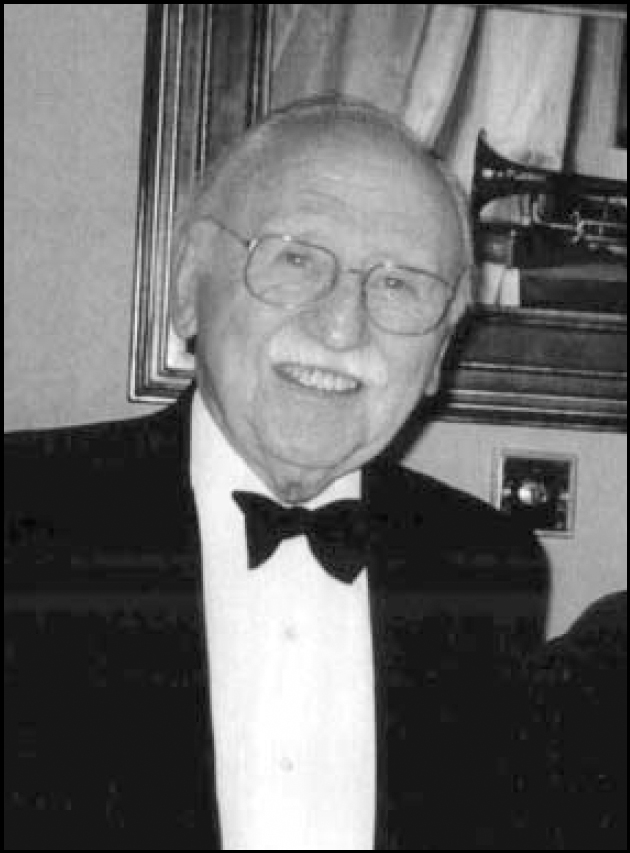

On 12 April 2004, the death occurred of one of the giants of twentieth century psychiatry. Don Early was the doyen of the industrial rehabilitation movement which contributed so much to the more enlightened treatment of chronic mental illness, the reduction of in-patient numbers and the move to community care.

He was born in Roscommon, Ireland on 20 May 1917, the tenth child of District Judge William Early and his wife Margaret. He was sent to boarding school at an early age and was educated at Clongoes Wood, West Kildare. Here he passed his leaving certificate but following the death of his father he was forced to leave school before his scholarship exams for financial reasons. He lived briefly on his farm in Tyrone where he met his future wife, Prudence Park. He was finally able to enter the College of Surgeons medical school, Dublin, where he qualified LRCPI and LM in 1941. He enjoyed college life, playing rugby and involving himself in amateur dramatics. On qualification he came to England and worked in Blackpool during the war, returning to Dublin to do his DPH and some initial psychiatric training at Grange Gorman Hospital, passing his DPM in 1945. He returned to England to join the staff at Bristol Mental Hospital in 1944. He married Prue in Ireland in 1946 and they came to Bristol to start their life together.

Like many medical advances, his ideas were born out of adversity and unpromising beginnings. When he came to Bristol Mental Hospital, most of the staff and resources had gone to the new Barrow Hospital which had been used by the military during the war. Don would greet new medical staff with ‘ Welcome to Devil's Island’, and then he said that he could offer them little but hard work and plenty of experience. With his example and good humour he, nevertheless, attracted a loyal and enthusiastic team and the opening of the Prichard Clinic allowed the treatment of acutely ill patients in more modern surroundings.

His appetite for work was phenomenal; he could never say no, so the number of patients at his clinics at both Frenchay and Southmead Hospitals was double or treble the norm. In addition, he spent many evenings and weekends in a flourishing private practice though many of his patients were what he called ‘ God reward mes’. He developed a unique method of explaining the relationship of depression and anxiety graphically, and most patients left clutching the piece of paper like a talisman.

It was in rehabilitation and industrial therapy that he made his mark. Institutionalisation was a major problem in all mental hospitals. Many long-stay patients were unemployed or working for pocket money in the various hospital departments. New treatments improved prognosis, which without proper employment discharge was impossible. In 1957, he enlisted the help of a local industrialist whose business relied on out-workers to assemble ball-point pens. This was started in the occupational therapy department and, by the end of 1958, one-third of the patients were working.

These new ideas worried the trade unions. He invited their representatives to visit the hospital and gained the support of the regional secretary of the Transport and General Workers Union. In March 1960, their General Secretary visited the new Industrial Therapy Organisation (ITO) factory in central Bristol. The factory thrived: a hand car wash was opened and properties were bought to provide intermediate sheltered housing. People were enabled to move out of the hospital via ITO into sheltered groups in open industry. In its heyday ITO (Bristol) became the model for similar developments throughout the UK and internationally.

Don was invited to become a World Health Organization advisor in Industrial Rehabilitation and visited Spain, Turkey, France, Italy, the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

When he retired from the NHS he had time to develop his longstanding interest in forensic psychiatry. He became actively involved in providing psychiatric reports for the Court; service of a consistently high, authoritative standard. He remained on the Board of Directors of ITO until its closure in 2003, having completed its task. He continued to take a great interest in his old hospital and was the founder and guiding light of the Glenside Hospital Museum, an interest that he continued until this year. In 2003 he finished writing and published The Lunatic Pauper Palace, documenting the history of Glenside Hospital Bristol 1861-1994.

For much of his time at Glenside he lived in a hospital house ‘ Clonora’ on Blackberry Hill, where he installed a swimming pool and held legendary barbecues in the garden for friends and colleagues. When he bought a run-down old rectory a few miles outside Bristol it was rumoured the he would open a ‘cow-wash’, but over the years he and his wife developed it into a magnificent home and garden with plenty of room for his beloved Irish wolfhounds and another swimming pool for the grandchildren. This was enclosed in a building made of rescued windows which were bought from the hospital during renovations.

In October 2001 he suffered a severe stroke and, tragically, never regained his power of speech. His wonderful smile and good humour rarely deserted him. He was a brave man loved by all who knew him.

Donal Early is survived by his wife Prudence, and two daughters - all three are doctors - and four grandchildren. He was pre-deceased by his grandson, Toby, a medical student, who died in 1996.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.