The care programme approach was introduced in UK in 1991 to formally coordinate care for people with a mental illness. Its role in UK psychiatry is currently under review - the Department of Health is considering abandoning the formal care programme approach altogether, except in severe and enduring mental illness (Department of Health, 2006). Implications of such a move have been addressed by the Royal College of Psychiatrists (Reference MorganMorgan, 2007).

Treatment adherence is a challenge in eating disorders. It has mainly been addressed therapeutically (Reference Feld, Woodside and KaplanFeld et al, 2001) or by consideration of service user variables (Reference ClintonClinton, 1996). However, service configurations and care coordination also affect adherence (Reference Arcelus, Bouman and MorganArcelus et al, 2007) and lack of care coordination contributes to poor outcomes (Reference Treasure, Schmidt and HugoTreasure et al, 2005).

There are many approaches to managing eating disorders in the UK and care can be delivered in a variety of settings. The importance of seamless care pathways has been stressed in the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2004), though they have been implemented piecemeal. In particular, NICE called for ‘agreement among individual healthcare professionals… in writing… using the Care Programme Approach’ (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2004).

Eating disorders are sometimes misconstrued as neither severe nor enduring, therefore possible changes to the care programme approach may impede application of NICE guidelines. The aim of this study was to describe and identify predictors of treatment adherence in a specialist eating disorder service by examining the use of the care programme approach and service user characteristics.

Method

Setting

The study was set in the Epsom eating disorder service, a specialist service which covers a suburban population in Surrey, south-east England. Service users are primarily referred from local primary care and secondary psychiatric services. Those referred out of area are not accepted. The service operates only as an out-patient clinic. Members of the team include psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, occupational therapists, counsellors and a dietician.

Design

We studied all service users assessed by the service over an 18-month period between September 2001 and the end of March 2003. Clinical data and other information were recorded for each person at presentation: age, gender, body mass index, the length of illness, waiting time for referral to the service, the source of referral and whether the person had been documented as subject to the UK's care programme approach.

The primary outcome measure was treatment adherence, defined in the study as ‘continuation or satisfactory completion of treatment’. Non-adherence was defined as ‘early unplanned drop-out or discharge due to non-attendance’. Effectiveness of treatment was not considered.

Questionnaires

All service users completed the Stirling Eating Disorder Scales (SEDS) at assessment. The SEDS is a self-reported, 80-item, 8-scale measure validated for use in people with eating disorders. It has an acceptable internal consistency, reliability, group validity and concurrent validity (Reference Williams, Power and MillerWilliams et al, 1994).

Clinical assessment

We used a clinical diagnostic interview as a gold-standard measure. The interview was conducted by eating disorder specialists with extensive experience in assessments and was based on DSM-IV criteria for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and eating disorders not otherwise specified (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). For each service user the researcher recorded age, gender, body mass index, length of illness, waiting time for assessment at the clinic and medical evaluation of nutritional status.

Service provision and data analysis

Participants were separated into two groups based on whether or not they were managed under the provisions of a documented care programme approach at the point of referral. It was noted where the follow-up was offered and whether the person accepted the referral to the Epsom eating disorder service's support group.

Data were analysed using SPSS version 10 for Windows, with both continuous and dichotomous scores.

Results

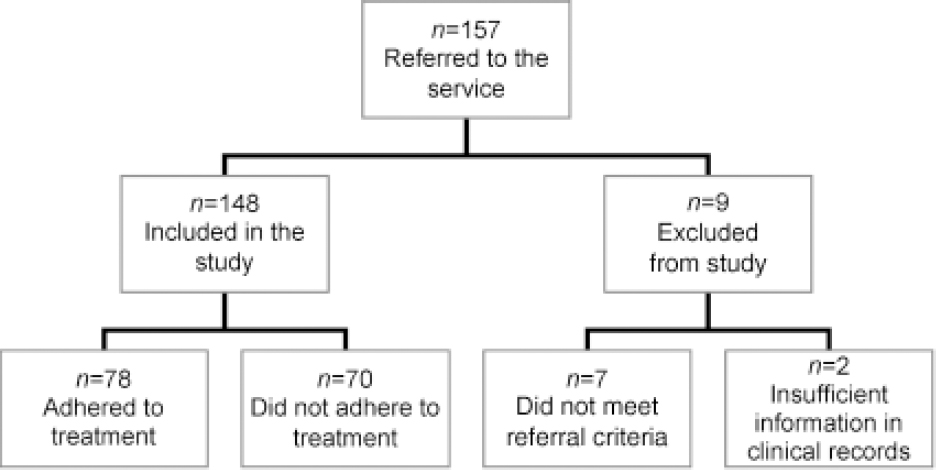

During the designated period, 157 individuals were referred to the service. Seven people referred to the service did not meet the referral criteria and two individuals had incomplete medical records. This left a sample size of 148 service users for data analysis.

Over half of the service users (n=78, 53%) adhered to treatment (treatment adherence as defined above; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Flow of participants through the study.

Characteristics of service users assessed by the service

Mean age of participants was 29 years (s.d.=10.7, range 16-70) and 80% were new to the service; 7% of individuals referred were male. Further characteristics were not available from the clinical records.

Most of the referred individuals were diagnosed with bulimia nervosa (46%), 26% had anorexia nervosa, 15% binge eating disorder, 2% other subtype of eating disorder not otherwise specified and 8% of diagnoses were not recorded on assessment. The average length of illness was 10 years (s.d.=8.03, range 1 month-36 years).

Sources of referral

Individuals were referred to the service mostly by community mental health teams (55%) and by their family doctor (42%). The rest were referred from addiction services, psychotherapy departments and medical clinics.

Care programme approach

Less than a third of participants (28%) were documented as on standard and 9% on enhanced care programme approach, with the remaining 63% with no documentation of care programme approach at the time of referral. The care programme is particularly targeted at generic psychiatric services - community mental health teams - but half of service users referred by those services did not have documentation relating to the care programme approach at the point of referral.

Treatment adherence

The application of the care programme approach, whether standard or enhanced, was highly predictive of future treatment adherence (Table 1). Service users with an identified care coordinator and care programme approach at the point of assessment were more likely to stay in treatment (P=0.002). Diagnostic category also predicted adherence - those with a diagnosis of anorexia were significantly (P=0.04) more likely to stay in treatment than other diagnostic groups. Participants who received follow-up by a dietician (P=0.03) and those who agreed to a referral to the eating disorder support group (P=0.02) were similarly more likely to stay in treatment. These findings were independent of diagnosis or severity of illness.

Table 1. Dichotomous predictors of treatment adherence

| Variable | Patients who were referred 1 n | Patients who attended n (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Care programme approach | 57 | 39 (68) | 2.89 (1.44–5.79) ** |

| Diagnosis of anorexia | 39 | 27 (69) | 2.25 (1.02–4.96) * |

| Follow-up | |||

| Dietetic | 61 | 47 (77) | 2.38 (1.06–5.35) * |

| Medical | 87 | 60 (69) | 1.11 (0.44–2.79) |

| Counselling | 39 | 29 (74) | 1.57 (0.66–3.72) |

| Psychological | 28 | 21 (78) | 1.53 (0.58–4.00) |

| Support group referral | 43 | 35 (81) | 2.85 (1.15–7.03) * |

** P<0.01

* P<0.05

1. Some patients were referred to more than one part of the service

The mean age of service users staying in treatment was higher (P=0.01), as was the mean length of illness (P=0.01), compared with those who dropped out early (Table 2). Other variables were not statistically significant in predicting adherence. However, in the absence of a priori power calculations, it is not possible to conclude if these are true ‘negatives’ or rather represent type II errors. Among the participant characteristics, the following did not predict non-adherence: gender, waiting time, severity of eating disorder as measured by the SEDS and body mass index at the point of assessment. With the exception of the consultation with a dietician, follow-up with any of the other professionals was also not predictive of adherence (Table 1).

Table 2. Continuous predictors of treatment adherence

| Treatment adherence n=78 | Treatment non-adherence n=70 | Independent samples t-test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | mean (s.d.) | mean (s.d.) | t | d.f. | P | ||

| Age, years | 30.4 (11.1) | 26.3 (7.86) | 2.62 | 146 | ** | ||

| BMI, km/m2 | 25.0 (9.65) | 24.9 (10.71) | 0.02 | 34.3 | |||

| Length of illness, years | 11.4 (8.39) | 7.72 (7.13) | 2.52 | 112 | ** | ||

| Waiting time, weeks | 6.45 (5.65) | 5.92 (4.38) | 0.54 | 86.2 | |||

| SEDS scores | |||||||

| ADC | 25.3 (10.2) | 26.6 (9.2) | –0.63 | 65.7 | |||

| ADB | 11.7 (8.93) | 12.5 (8.41) | –0.41 | 63.5 | |||

| BDC | 28.9 (10.7) | 32.6 (10.2) | –1.56 | 62.8 | |||

| BDB | 22.3 (13.1) | 24.7 (10.7) | –0.95 | 71.5 | |||

| HPEC | 17.0 (10.2) | 13.6 (8.32) | 1.73 | 71.7 | * | ||

| LA | 21.8 (8.34) | 18.7 (9.18) | 1.54 | 55.2 | |||

| LSE | 24.2 (8.71) | 22.2 (7.65) | 1.13 | 67.5 | |||

| SDH | 23.5 (11.4) | 20.5 (8.78) | 1.41 | 75.5 | |||

ABD, anorexic dietary behaviours; ADC, anorexic dietary cognitions; BDB, bulimic dietary behaviours; BDC, bulimic dietary cognitions; BMI, body mass index; HPEC, high perceived external control; LA, low assertiveness; LSE, low self-esteem; SDH, self-directed hostility; SEDS, Stirling Eating Disorder Scale

** P<0.01

* P<0.05

Discussion

This study suggests the utility of the care programme approach in improving treatment adherence in eating disorders. It underlines the need for special measures in improving adherence, particularly in individuals with bulimia and eating disorders not otherwise specified. It also highlights the particular benefits of access to dietetic advice and a support group at an early stage in treatment.

Care programme approach

The care programme approach is currently under intense scrutiny in the UK, although it has become a cornerstone of UK psychiatry. Initially, it required better coordination between health and social services, but it was further developed in 1999 in the document Effective Care Coordination in Mental Health Service - Modernising the Care Programme Approach (Department of Health, 1999a ) and later in the UK National Service Framework for Mental Health (Department of Health, 1999b ). Strengths of the care programme approach include the active involvement of service users and their carers, a multidisciplinary and proactive approach to care, assigning each service user a care coordinator, and regular and systematic review of needs.

In its current review of the care programme approach, the Department of Health acknowledges its principles are useful, but implementation and practice require revision (Department of Health, 2006). At present, there are two levels of the care programme, a standard level for the majority of service users and an enhanced level for those with the most complex needs. It has been proposed (Department of Health, 2006) that there should only be one level of the care programme approach, effectively removing the standard level and maintaining only the enhanced level. Improving the utility of the approach was also reviewed by the Department of Health, with concern that it has become a managerial, bureaucratic tool rather than a means of engaging with people.

The results of our study suggest that appropriate use of integrated care planning can indeed allow specialist eating disorder services to engage service users more fully, resulting in better treatment adherence. In our opinion, the care programme approach has been helpful in establishing partnerships between generic psychiatric services and specialist eating disorder services and this may explain the positive findings of this study.

Motivational enhancement for individuals with eating disorders not otherwise specified

Better treatment adherence in individuals with anorexia nervosa may simply reflect their appreciation of heightened physical and psychological risk. However, non-engagement of individuals with eating disorders not otherwise specified may reflect how poorly we serve this group in terms of evidence-based treatment and indeed DSM-IV nosology (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

Regardless of explanation, the poorer engagement with services of individuals with eating disorders not otherwise specified suggests the need for focusing resources on motivational enhancement and equivalent therapies.

Follow-up by a dietician

The clear benefits of follow-up by a dietician may reflect the particular skills of the dietician in the service being scrutinised, or the benefits of dietetic advice at a germinal stage of engagement with the service.

Support group

Agreement to be referred to a support group seems to be a strong proxy indicator of a service user's motivation to change. Individuals who are unwilling to reflect on their illness within a supportive peer group are much more likely to fall in a ‘pre-contemplative’ category of ‘readiness to change’.

Limitations of the study

This study has the strengths of being carried out in a representative setting with a large sample size, but it also contains a number of weaknesses. We were unable to analyse treatment adherence according to ethnicity and socio-economic background, thus leaving unanswered the important question of how to engage minority groups in eating disorder interventions. This study was purely utilitarian and left no room for acknowledging service users’ or carer's opinions. Given the absence of previously published data, we were unable to conduct power calculations in advance of the study. Thus, the absence of statistically significant associations in some areas should not be regarded as representing ‘true negatives’, but might instead reflect type II errors. It is plausible that individuals referred under the care programme approach had a greater severity of illness or comorbidity and it is all the more striking that this group had improved outcomes as compared with those who were not on care programme approach at referral. Although data on comorbid illnesses were limited, none of the individuals was diagnosed with psychosis. It is therefore unlikely that differences between the groups can be explained by comorbidities separate to the eating disorder alone. Finally, this study is only capable of demonstrating associations and not causal relations, such that our commentary on causality is speculative.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that proper integrated care coordination, such as the care programme approach, may play a significant role in improving treatment adherence. Specialist eating disorders services may wish to consider the benefits of requiring formal care coordination before accepting individuals referred from other health agencies. Providing timely assessments with empathic therapists is more important than the professional discipline of the assessor, although early dietetic advice may improve treatment adherence. The study generates more hypotheses than it tests, but it does suggest that future research should examine the structure of clinical services and care pathways with as much vigour as the examination of specific treatments.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.