Introduction

With around 300 million affected individuals worldwide, major depressive disorder (MDD) is a highly prevalent and debilitating mental illness not only for those that are affected, but also for society at large (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Chatterji, Lee, Ormel and Wang2009). Even though psychotherapy and anti-depressant medication have been found to improve depressive symptom severity as monotherapy or in combination (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Noma, Karyotaki, Vinkers, Cipriani and Furukawa2020), treatment resistance and relapse rates remain high (Holtzheimer & Mayberg, Reference Holtzheimer and Mayberg2011; Rush et al., Reference Rush, Trivedi, Wisniewski, Nierenberg, Stewart, Warden and Fava2006). To better understand the challenges and barriers to successful depression treatment, this study aimed to explore the role of personality pathology. Previous studies found that around 45% of patients with MDD suffer from comorbid personality disorders (PDs; Friborg et al., Reference Friborg, Martinsen, Martinussen, Kaiser, Overgård and Rosenvinge2014) and MDD is associated with a distinct profile of personality traits including lower emotional stability, extraversion, and conscientiousness (Hakulinen et al., Reference Hakulinen, Elovainio, Pulkki-Råback, Virtanen, Kivimäki and Jokela2015; Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt, & Watson, Reference Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt and Watson2010). However, patients with MDD are also highly heterogeneous in their pattern of personality problems (Cain et al., Reference Cain, Ansell, Wright, Hopwood, Thomas, Pinto and Grilo2012; Simon, Cain, Wallner Samstag, Meehan, & Muran, Reference Simon, Cain, Wallner Samstag, Meehan and Muran2015), which could be a potential indicator of differential trajectories of change in depression treatments. In the following, based on data from an randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing two different psychotherapeutic treatments in depressed inpatients (N = 193), we investigated (1) whether maladaptive personality traits are associated with changes in depressive symptoms and/or vice versa, (2) whether maladaptive personality traits change over the course of treatment, (3) if this change depends on the type of treatment, and (4) if maladaptive personality traits moderate the effectiveness of different treatment types. Our results may inform clinical decisions on the suitability of specific interventions for the individual patient.

Personality pathology may be a promising candidate for treatment response prediction in depression. Based on meta-analytic evidence from prospective case series and RCTs, Newton-Howes et al. (Reference Newton-Howes, Tyrer, Johnson, Mulder, Kool, Dekker and Schoevers2014) showed that comorbid PDs doubled the odds of poor treatment outcomes in depressed patients regardless of the type of treatment. A more recent meta-analysis restricted to RCTs of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) reported similar results overall. However, the adverse impact of PDs on treatment course of depression diminished in subgroup analyses that only included high-quality studies or when adjusting meta-analytic effect estimates for baseline depression severity (Banyard, Behn, & Delgadillo, Reference Banyard, Behn and Delgadillo2021). Therefore, the predictive utility of personality pathology in treatments of MDD remains unclear. It also remains unclear whether and to what extent pre-treatment depressive symptom levels influence the malleability of personality pathology over treatment itself as suggested by Hellerstein et al. (Reference Hellerstein, Skodol, Petkova, Xie, Markowitz, Yen and McGlashan2010). This would indicate a bi-directional relationship between depression and personality pathology over the course of treatment. It is important to note, however, that all of these prior studies relied upon the outdated categorical approach for PD classification, which has been criticized regarding its lack of clinical utility, reliability, and validity (Hengartner, Zimmermann, & Wright, Reference Hengartner, Zimmermann, Wright, Zeigler-Hill and Shackelford2018).

Studies employing dimensional measures of personality have traditionally largely focused on the Big Five traits, and indeed provided some evidence for associations with treatment response (Bucher, Suzuki, & Samuel, Reference Bucher, Suzuki and Samuel2019). In depressed patients, lower scores on emotional stability, extraversion, and openness have been observed to be predictive of poorer treatment outcomes (Quilty et al., Reference Quilty, De Fruyt, Rolland, Kennedy, Rouillon and Bagby2008). The Big Five also appear to be changeable following clinical interventions and a recent meta-analysis found that particularly emotional stability/neuroticism and extraversion increased following treatment (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Luo, Briley, Chow, Su and Hill2017). These personality traits are most strongly linked to individuals' affect, whereby neuroticism is associated with negative and extraversion with positive affect (McNiel & Fleeson, Reference McNiel and Fleeson2006). As a consequence, these traits may constitute ideal intervention targets as psychotherapeutic techniques aim to increase positive (e.g. fostering rewarding social interactions) and decrease negative affect (e.g. fostering strategies to cope with self-criticism). Overall, this research indicates the potential benefit of assessing personality traits dimensionally in clinical psychiatric contexts. The Big Five depict common personality features, however, and were not constructed to capture maladaptive variants of personality such as the dimensional classification approaches incorporated in the DSM-5 and ICD-11 (APA, 2013; Tyrer, Mulder, Kim, & Crawford, Reference Tyrer, Mulder, Kim and Crawford2019). For example, in the Alternative Model for Personality Disorders (AMPD) in DSM-5 Section III (Krueger, Derringer, Markon, Watson, & Skodol, Reference Krueger, Derringer, Markon, Watson and Skodol2012), PDs are classified dimensionally in terms of impairments in personality functioning (criterion A) and maladaptive personality traits (criterion B). Criterion B comprises a hierarchical model including five maladaptive trait domains (negative affectivity, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, psychoticism) on a higher level and 25 trait facets at a subordinate level. Four of the five maladaptive trait domains are substantially associated with the Big Five and can therefore be considered as maladaptive variants of the Big Five (i.e. negative affectivity is negatively associated with emotional stability, detachment with extraversion, agreeableness with antagonism, and conscientiousness with disinhibition; Suzuki, Griffin, & Samuel, Reference Suzuki, Griffin and Samuel2017). To date, it remains unclear whether maladaptive personality traits are changeable following treatment and if they can predict treatment response in depression.

Psychotherapeutic treatments for depression differ in the extent that they were meant to target personality pathology. The recommended first-line treatment for depression (Middleton, Shaw, Hull, & Feder, Reference Middleton, S.haw, Hull and Feder2005) is CBT (Beck, Reference Beck1976; Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979), which primarily aims to improve MDD severity by altering depressive cognitive appraisals (e.g. ‘I am worthless and the future is hopeless’) and dysfunctional behaviours such as social withdrawal and physical inactivity (Garratt, Ingram, Rand, & Sawalani, Reference Garratt, Ingram, Rand and Sawalani2007). In contrast, schema therapy (ST) was originally developed for the treatment of CBT non-respondents including patients with PDs (Young, Reference Young1990) and targets so-called early maladaptive schemas (EMSs; Young, Klosko, & Weishaar, Reference Young, Klosko and Weishaar2003) such as ‘Emotional deprivation’ or ‘Failure’. In ST, EMSs are considered as dysfunctional trait-like patterns of thoughts, memories, emotions, physical sensations, and attention tendencies, which are relatively enduring and repeatedly re-activated throughout life. They are believed to emerge during early childhood and particularly in adverse social environments including emotional neglect or physical abuse, in which the child's basic psychological needs such as attachment or autonomy are unmet. Recently, a large overlap between ST concepts and maladaptive personality traits has been reported (Bach & Bernstein, Reference Bach and Bernstein2019; Bach, Lee, Mortensen, & Simonsen, Reference Bach, Lee, Mortensen and Simonsen2016), which may indicate that ST is particularly well equipped for the treatment of maladaptive trait domains. Specifically, although CBT tries to challenge dysfunctional cognitions, for example using Socratic dialogue, and to reduce dysfunctional behaviours through behavioural activation (Sudak, Reference Sudak2012), ST applies more experiential and emotion-focused strategies such as imagery rescripting, mode dialogues on chairs, and ‘limited reparenting’ techniques (Young et al., Reference Young, Klosko and Weishaar2003). In an initial RCT, ST was found to be similarly effective in the treatment of depression compared to CBT (Carter et al., Reference Carter, McIntosh, Jordan, Porter, Frampton and Joyce2013). ST was also found to be effective in the treatment of PDs (Bamelis, Evers, Spinhoven, & Arntz, Reference Bamelis, Evers, Spinhoven and Arntz2014). To date, however, no study has been conducted investigating whether ST is better suited than CBT for the treatment of maladaptive personality traits in depressed patients.

Conversely, it is also unclear if ST or CBT are more effective in the treatment of depression in individuals with certain maladaptive personality traits. Addressing these questions could help to come closer to answering the old but pressing question ‘What works best for whom’ (Paul, Reference Paul1967).

The present study

This study used data from an RCT comparing CBT and ST in patients with depression in psychiatric and day clinical settings (Kopf-Beck et al., Reference Kopf-Beck, Zimmermann, Egli, Rein, Kappelmann, Fietz and Keck2020). Based on the mixed meta-analytic findings of Newton-Howes et al. (Reference Newton-Howes, Tyrer, Johnson, Mulder, Kool, Dekker and Schoevers2014) and Banyard et al. (Reference Banyard, Behn and Delgadillo2021), we first explored whether higher pre-treatment levels of maladaptive trait domains were associated with smaller changes in depression symptom severity from pre- to post-treatment, and/or vice versa. Second, we investigated the changeability of the five maladaptive trait domains over the course of treatment and hypothesized their reduction particularly for negative affectivity and detachment in line with previous findings on corresponding Big Five traits (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Luo, Briley, Chow, Su and Hill2017). Third, we tested differential effectiveness of CBT and ST in targeting maladaptive trait domains and hypothesized that ST would outperform CBT as it was specifically developed for the treatment of PDs. Finally, we examined whether the maladaptive trait domains moderate differential treatment effects of ST and CBT in depression.

Methods

Sample

We used data from the OPTIMA study (OPtimized Treatment Identification at the MAx Planck Institute of Psychiatry; Kopf-Beck et al., Reference Kopf-Beck, Zimmermann, Egli, Rein, Kappelmann, Fietz and Keck2020), an RCT investigating the effectiveness of CBT, ST, and individual supportive therapy (IST) in depressed patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital for inpatient or day clinic treatment. Inclusion criteria comprised a primary diagnosis of depression with at least moderate severity. This was rated as ⩾20 according to Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Hautzinger, Keller, & Kühner, Reference Hautzinger, Keller and Kühner2009) or the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (Montgomery & Åsberg, Reference Montgomery and Åsberg1979). Additional requirements were proficiency in the German language and age between 18 and 75 years. Main exclusion criteria were lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, acute psychotic disorder, acute suicidality, concomitant substance use disorder, or organic mental disorders (for more details see Kopf-Beck et al., Reference Kopf-Beck, Zimmermann, Egli, Rein, Kappelmann, Fietz and Keck2020). Clinical diagnoses of depression and comorbid mental disorders were assessed by trained raters using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). This study was conducted in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki Standards and all patients provided written informed consent prior to participation.

In total, N = 300 depressed patients fulfilled inclusion criteria and were randomized in a parallel group design to CBT, ST, or IST. For the purpose of this study, we selected participants randomized to the ST and CBT treatment arm (N = 199). We focused on ST and CBT because these conditions enabled us to perform a theory-driven test as to whether a psychotherapy developed for the treatment of non-responsive patients with PD characteristics (i.e. ST) was superior to the gold-standard psychotherapy for depression (i.e. CBT) in reducing maladaptive personality traits. However, we repeated the analyses regarding the first and second research questions using data from the full sample.

Altogether six participants were excluded since they (i) did not reach the defined cut-off score for depression (n = 2), (ii) dropped out before receiving the first psychotherapy session (n = 1), (iii) failed to complete baseline questionnaires before commencing treatment (n = 2), or (iv) fulfilled an exclusion criterion that was identified retrospectively (n = 1). This resulted in a final sample of N = 193 participants (53.4% women, M age = 42.9, s.d. = 13.4). Patients reported an average BDI-II pre-treatment score of 31.4 (s.d. = 8.7) indicating severe depressive symptoms. Average pre-treatment mean scores of PID-5-FBF domain scales ranged from ‘normal’ to clinically elevated ‘mild’ levels with 0.55 (T53) for psychoticism and 1.21 (T61) for detachment, respectively (Rek, Kerber, Kemper, & Zimmermann, Reference Rek, Kerber, Kemper and Zimmermann2021). However, there was also substantial heterogeneity between patients as indicated in ranges from normal to clinically relevant levels (online Supplementary Fig. S1). About 28% of patients who completed the Assessment of DSM-IV Personality Disorders (ADP-IV; Doering et al., Reference Doering, Renn, Höfer, Rumpold, Smrekar, Janecke and Schüßler2007) qualified for a comorbid PD (see online Supplementary Table S1). At pre-treatment, patients of both treatment arms did not differ with regards to socio-demographic characteristics and psychiatric symptom severity (see Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical variables at baseline (N = 193)

CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; ST, schema therapy; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; s.d., standard deviation.

*p < 0.01; **p < 0.001.

Intervention

After providing informed consent and completing baseline assessment (see Kopf-Beck et al., Reference Kopf-Beck, Zimmermann, Egli, Rein, Kappelmann, Fietz and Keck2020 for details), patients received a course of psychotherapy for 7 weeks. In addition to psychotherapy, patients received inpatient/day-clinic treatment as usual including pharmaco-, exercise-, socio-, and/or occupational-therapy (see online Supplementary material for additional information on concomitant treatments). During the intervention phase, patients received two group (100 min each) and two individual (50 min each) manual-based therapy sessions per week and were excluded if they missed more than six out of a maximum of 28 psychotherapy sessions. To ensure adherence with the study manuals and quality, trial therapists were trained by leading experts in CBT and ST and received monthly supervision. Therapy sessions were videotaped and a randomly selected subsample rated by two independent raters indicated high to very adherence to the manual. Regarding concomitant pharmacotherapy regimens, there were no significant differences between treatment arms (see online Supplementary Table S2).

The interventions are described in more detail in Kopf-Beck et al. (Reference Kopf-Beck, Zimmermann, Egli, Rein, Kappelmann, Fietz and Keck2020). Briefly, CBT was based on a modified and extended version of an established treatment manual for MDD by Hautzinger (Reference Hautzinger2013). The manual consists of five modules including (a) psychoeducation, (b) behavioural activation, (c) modification of dysfunctional attitudes and automatic thoughts, (d) social competence training, and (f) relapse prevention. ST was delivered according to the ST manual designed for a psychiatric inpatient and day clinic setting (Egli et al., Reference Egli, Frieß, Graf, Höhn, Kopf-Beck and Rein2019). The manual contains three treatment phases with the main focus on (a) psychoeducation, (b) modification of EMS and dysfunctional modes, and, (c) exercises on strategies for transfer and relapse prevention.

Measures

PID-5-FBF and BDI-II were assessed at pre- and post-treatment for main analyses. The self-report version of the ADP-IV was used for additional description of the sample (see details in online Supplementary material). Note that the ADP-IV was added to the study later on, so was only available for a subset of patients.

Beck Depression Inventory II

We used the German version of the BDI-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, Reference Beck, Steer and Brown1996; German version: Hautzinger et al., Reference Hautzinger, Keller and Kühner2009) to assess the severity of depressive symptoms. The self-report scale entails 21 items, which are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. Higher scores indicate greater depressive symptom levels. Psychometric properties of the scale have been reported in previous research (Kühner, Bürger, Keller, & Hautzinger, Reference Kühner, Bürger, Keller and Hautzinger2007). For our analyses, we computed three BDI parcels by splitting the items into three groups of 7 items each and computing the mean score. See online Supplementary materials for details on psychometric properties.

Personality inventory for DSM-5 faceted brief form (PID-5-FBF)

The German version (Zimmermann et al., Reference Zimmermann, Altenstein, Krieger, Holtforth, Pretsch, Alexopoulos and Leising2014) of the 100-item (Maples et al., Reference Maples, Carter, Few, Crego, Gore, Samuel and Miller2015) self-report questionnaire PID-5 (Krueger et al., Reference Krueger, Derringer, Markon, Watson and Skodol2012) entails 25 subscales representing the trait facets of AMPD's trait model. The three most important facets were used to define each of the five maladaptive trait domains (i.e. negative affectivity, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, and psychoticism). The items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = very false to 3 = very true, with higher scores indicating greater personality pathology. See online Supplementary materials for details on psychometric properties.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using statistical software R (R Core Team, 2020) and the psych (Revelle, Reference Revelle2020), lavaan (Rosseel et al., Reference Rosseel, Oberski, Byrnes, Vanbrabant, Savalei, Merkle and Barendse2018), and EffectLiteR packages (Mayer, Dietzfelbinger, Rosseel, & Steyer, Reference Mayer, Dietzfelbinger, Rosseel and Steyer2016). Scripts for analyses are available in the online Supplementary material.

Throughout the first three research questions, we used latent change score (LCS; McArdle, Reference McArdle2009) models with multiple indicators and scalar measurement invariance across time for each construct (see Fig. 1). Maladaptive trait domains were defined by the three most relevant PID-5-FBF facet scores, and depressive symptoms were defined by three parcels each consisting of seven BDI items. To address the first research question, we used five bivariate LCS models (panel a), each time including depressive symptoms and one of the five maladaptive trait domains. The focal parameters γ1 and γ2 (i.e. ‘cross-domain coupling’; Kievit et al., Reference Kievit, Brandmaier, Ziegler, van Harmelen, de Mooij, Moutoussis and Dolan2018) represent the extent to which changes in construct X (e.g. depressive symptoms) between pre- and post-treatment are a function of construct Y (e.g. detachment) at pre-treatment, while controlling for pre-treatment values of construct X,or vice versa. To test our second research question on the changeability of the maladaptive trait domains from pre- to post-treatment, five univariate LCS models (panel b) were estimated. Particularly, we tested the (unconditional) intercept of change in the maladaptive trait domain (Δμ domain) for significance. Third, treatment effects (β) of ST v. CBT on changes in the five maladaptive trait domains were tested by including treatment as predictor in univariate LCS models (panel c).

Fig. 1. LCS models to address research questions 1–3. Dashed lines show effects and variances fixed to zero and ‘1's indicate effects fixed to 1. Lines with two arrowheads represent (co-)variances while lines with one arrowhead show regression effects. Circles indicate latent variables, rectangles display manifest variables, and triangles show intercepts. Intercepts and residual variances of manifest variables are omitted. All LCS models depicted in this figure are based on scalar measurement invariance, whereby loadings and intercepts of manifest variables (i.e. parcels and core facets) are fixed to be equal, but residual variances are allowed to be different across time. (a) Bivariate LCS model, which uses regressions of change scores on baseline levels to assess the extent to which changes in depressive symptoms between pre- (T1) and post-treatment (T2) are a function of baseline maladaptive traits (γ1), vice versa (γ2) or both. In the bivariate LCS model, associations between depressive symptoms and maladaptive traits at pre-treatment (Φ) as well as between depressive symptom and maladaptive trait change scores (ρ) were also explored. (b) (Unconditional) univariate LCS model, in which the effect of interest was the intercept of change (Δμ) and the association of baseline maladaptive traits and maladaptive trait change score was modelled as a covariance. (c) Analyses of the treatment covariate. In this model, the association of baseline maladaptive traits and maladaptive trait change scores was modelled as a self-feedback effect as in bivariate LCS models.

Finally, to explore whether the treatment effects are moderated by the five maladaptive trait domains, we applied multi-group structural equation modelling using EffectLiteR (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Dietzfelbinger, Rosseel and Steyer2016, Reference Mayer, Zimmermann, Hoyer, Salzer, Wiltink, Leibing and Leichsenring2020). This approach not only allows for testing whether there is an average effect of CBT compared to ST with regards to depressive symptoms, but it also estimates whether treatment effects are conditional on pre-treatment maladaptive trait domains. In particular, we estimated a structural equation model with two groups (CBT and ST), using post-treatment depressive symptoms as the latent outcome variable, pre-treatment depressive symptoms as a latent covariate and the five maladaptive trait domains as observed covariates. EffectLiteR provides an omnibus test for the null hypothesis that there are no interactions between treatment condition and covariates (i.e. that effects of covariates do not differ between groups).

Across analyses, missing values in structural equation models were handled using a full information maximum likelihood approach (Enders & Bandalos, Reference Enders and Bandalos2001). To account for multiple comparisons, a conservative alpha error rate of 0.01 was selected, which equals Bonferroni correction with alpha error rate of 0.05 for statistical tests across five maladaptive personality traits.

Results

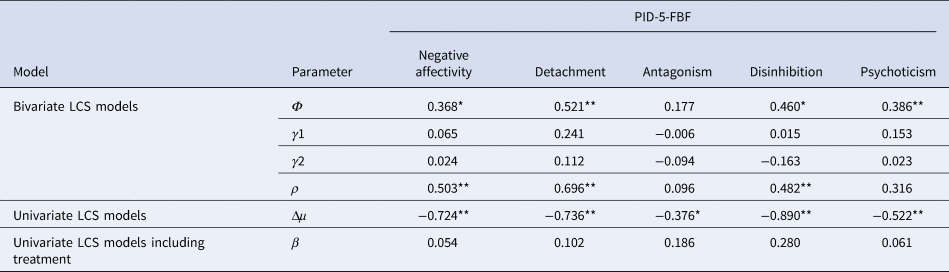

Table 2 summarizes the focal standardized parameter estimates from the LCS models (see online Supplementary Table S3 for fit indices). Maladaptive traits and depressive symptoms did not show cross-domain coupling using bivariate LCS models (i.e. γ1 and γ2 were non-significant). Accordingly, pre-treatment levels of the respective maladaptive trait domains were not associated with rates of change in depressive symptom severity over the course of treatment, or vice versa. Yet, with the exception of antagonism, we observed substantial correlations of maladaptive trait domains with depressive symptoms at pre-treatment (standardized Φ ranged from 0.37 to 0.52) and residuals of their respective change scores (standardized ρ ranged from 0.32 to 0.70). Repeating the analyses including the IST condition showed the same pattern of results, although there was evidence for a small cross-coupling effect of baseline detachment on changes in depressive symptoms (online Supplementary Table S4).

Table 2. Standardized parameters of LCS models

LCS, latent change score; PID-5-FBF, Personality Inventory for DSM-5 Faceted Brief Form.

Note. Analyses are based on the final sample of n = 193. Φ = depression and maladaptive trait domain correlation at baseline; γ1 = cross-domain coupling: trait domain score at baseline predicting rate of change in depression; γ2 = cross-domain coupling: depression score at baseline predicting rate of change in trait domain; ρ = correlated residuals of depression and maladaptive trait domain change scores; Δμ = intercept of maladaptive trait domain change score; β = effect of treatment group on change scores of maladaptive trait domains.

*p < 0.01; **p < 0.001.

Applying univariate LCS models, negative change score intercepts for each of the maladaptive traits were observed after 7 weeks of psychiatric treatment for depression (standardized Δμ domain ranged from −0.38 to −0.89; see Fig. 2). Results from these analyses – and analyses including the IST condition (see online Supplementary Table S4) – indicated that maladaptive traits can change during clinical interventions, particularly negative affectivity, detachment, and disinhibition. Analysing individual facets to explore results further indicated largest changes for depressivity, anxiousness, anhedonia, distractibility, and withdrawal (online Supplementary Fig. S3). When adding the treatment condition (CBT v. ST) as an additional predictor to the univariate LCS models, both treatment types were comparably effective in the reduction of the five maladaptive traits (i.e. β was non-significant).

Fig. 2. Standardized mean changes in maladaptive traits following treatment as estimated using univariate LCS models (see Table 2). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals for standardized mean change scores. See online Supplementary Figure S3 for standardized mean changes broken down to individual maladaptive personality facet scores.

Results of the multi-group structural equation modelling based on EffectLiteR indicated that the average treatment effect on post-treatment depressive symptoms was not significant (Wald χ2 = 2.80, df = 1, p = 0.09; see online Supplementary Table S5 for fit indices and online Supplementary Table S6 for regression coefficients), suggesting a comparable effectiveness of CBT and ST in the treatment of depression. In addition, we found no evidence for conditional treatment effects indicated by covariate-treatment interactions (Wald χ2 = 6.38, df = 6, p = 0.38).

Discussion

Due to the high rates of relapse and non-response in depression, it is key to identify factors that may obstruct treatment responsiveness and could inform treatment selection for the individual patient (Cohen & DeRubeis, Reference Cohen and DeRubeis2018; Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, DeRubeis, Shelton, Hollon, Amsterdam and Gallop2009). Using RCT data, we investigated the role of personality pathology over the course of 7-week inpatient or day clinic depression treatments by studying the impact and changeability of maladaptive personality traits according to the recently developed AMPD. Our results indicated that maladaptive traits were not predictive of changes in depressive symptomatology at post-treatment, or vice versa. Moreover, while we observed overall reductions in maladaptive traits at the end of treatment, changes were similar in magnitude in CBT and ST arms consistent with the null hypothesis of an absence of differential treatment effectiveness. Finally, inter-individual differences in maladaptive traits prior to treatment could not inform favourable allocation to CBT v. ST in the treatment of depression. While these findings did not provide suggestions for new treatment targets or allocation choices, they again disconfirm the old clinical myths that personality pathology is stable over time, not amenable to change, and worsens treatment outcomes of depressed patients.

Previous meta-analyses reported that personality pathology negatively impacts psychotherapeutic treatment outcomes of depressed patients (Banyard et al., Reference Banyard, Behn and Delgadillo2021; Newton-Howes et al., Reference Newton-Howes, Tyrer, Johnson, Mulder, Kool, Dekker and Schoevers2014). Notably, Banyard et al. (Reference Banyard, Behn and Delgadillo2021) conducted several sensitivity analyses in subgroups of high-quality trials and adjusting for baseline depression severity to assess the robustness of effects. Results of these sensitivity analyses are in line with our results showing no detrimental effects of the five maladaptive trait domains on treatment outcome. Our findings support a co-occurrence of personality pathology and depression levels at pre-treatment and co-occurrence of their respective change scores during treatment. Baseline co-occurrence of the two constructs in our study suggests that depressed patients with greater levels of personality pathology may be more severely depressed at pre-treatment. This has also been reported by Banyard et al. (Reference Banyard, Behn and Delgadillo2021), who stated that ‘[t]he apparent effect of PD on depression outcomes is likely explained by higher intake severity rather than treatment resistance’. Regarding the associated change scores of maladaptive trait domains and depression, more research is needed to investigate the observed correlations due to challenges of their interpretation in intervention studies (Könen & Karbach, Reference Könen and Karbach2021). As such, putative explanations may be a shared underlying process/transdiagnostic factor such as emotion dysregulation targeted during treatment (Abdi & Pak, Reference Abdi and Pak2019) or a third variable such as therapeutic alliance that affects both changes (Horvath, Del Re, Flückiger, & Symonds, Reference Horvath, Del Re, Flückiger and Symonds2011). However, results could also indicate that reciprocal, more dynamic processes of changes in maladaptive trait domains and depression levels occurred, which we were not able to capture with two time points only. Thus, future research should investigate the potential underlying variables/processes, while using more frequent assessment time points to capture potential dynamic processes of change (Renner et al., Reference Renner, DeRubeis, Arntz, Peeters, Lobbestael and Huibers2018).

PDs have originally been conceptualized and defined as ‘an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that […] is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment’ (APA, 2013, p. 685). The stability of personality pathology has been supported by Wright et al.'s (Reference Wright, Calabrese, Rudick, How, Zelazny, Williams and Simms2015) observational study on maladaptive trait domains’ mean-level change and rank-order stability over a time period of 1.4 years. Additionally, Zimmermann et al. (Reference Zimmermann, Mayer, Leising, Krieger, Grosse Holtforth and Pretsch2017) found that individual differences in maladaptive traits were relatively stable and rarely affected by situational factors. In the context of these findings, we observed substantial decreases in maladaptive traits after a relatively time-limited psychiatric inpatient treatment period of 7 weeks, which highlights the potential of clinical interventions to enable changes in personality pathology. Here, besides disinhibition among the largest reductions were observed for negative affectivity and detachment, which aligns with Roberts et al.'s (Reference Roberts, Luo, Briley, Chow, Su and Hill2017) meta-analytic findings of general adaptive changes in Big Five traits that included particularly pronounced increases in emotional stability (opposite pole of negative affectivity) and extraversion (opposite pole of detachment) over the course of treatment. Of note, emotional stability has been associated with lower levels of negative affect and extraversion with greater positive affect (McNiel & Fleeson, Reference McNiel and Fleeson2006) and clinical interventions for depression specifically target these traits. In sum, we show evidence in favour of the malleability of personality pathology during clinical interventions at least in the short run, which may reassure clinical practitioners. However, investigation of long-term effectiveness of such short clinical interventions for personality pathology is warranted (e.g. by using follow-up data of at least 6 months).

Contrary to our expectations, we observed no differences in average effects of ST and CBT in the treatment of maladaptive trait domains and no benefit of using these traits to inform personalized treatment choice to ST or CBT. These results could be explained by an overall relatively low treatment dosage and short treatment duration of 7 weeks for ST, for which effectiveness has been observed to increase with the overall number of sessions and time of treatment (Jacob & Arntz, Reference Jacob and Arntz2013). Alternatively, identification of specific psychotherapeutic treatment effects may have been obfuscated by the psychiatric inpatient setting, in which patients continued to receive standard care (e.g. pharmaco- or exercise therapy) during the course of treatment. These concomitant interventions have been shown to be effective treatments on their own (Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, DeRubeis, Hollon, Dimidjian, Amsterdam, Shelton and Fawcett2010; Kvam, Kleppe, Nordhus, & Hovland, Reference Kvam, Kleppe, Nordhus and Hovland2016), so replication in an outpatient setting and/or including a separate treatment arm for pharmacotherapy is warranted. However, our findings also align well with numerous studies showing equal effectiveness of different psychotherapies in line with the ‘Dodo Bird Verdict’ (Wampold, Reference Wampold2015). That is, factors that are common to different therapeutic approaches such as therapeutic alliance or empathy are assumed to explain most of the variance in treatment outcome (30–70%; Imel & Wampold, Reference Imel, Wampold, Brown and Lent2008). Finally, different forms of psychotherapies may indeed be comparable in their effectiveness but this effectiveness could be mediated by different mechanisms (DeRubeis, Brotman, & Gibbons, Reference Derubeis, Brotman and Gibbons2005). Thus, more research is needed to advance our understanding on the optimal treatment duration of ST for personality pathology, which is currently underway (Kool et al., Reference Kool, Van, Bartak, de Maat, Arntz, van den Eshof and Dekker2018), and on investigating mechanisms underlying different psychotherapeutic interventions.

Limitations

Our study needs to be interpreted in light of its limitations. First and foremost, the assessment of maladaptive trait domains and depression was only based on self-reports. Compared to other forms of psychopathology, PDs are considered to be relatively ego-syntonic meaning that affected individuals often present with poor insight or little awareness into their dysfunctional patterns of thoughts and behaviours. As such, self-reports such as the PID-5-FBF may be confounded by distorted representations of self and others (i.e. impairments of identity and empathy; APA, 2013) or alternatively, by a negative affect bias of depressed patients. Thus, future studies may benefit from inclusion of clinical expert ratings (Morey, Krueger, & Skodol, Reference Morey, Krueger and Skodol2013) or informant reports (Markon, Quilty, Bagby, & Krueger, Reference Markon, Quilty, Bagby and Krueger2013). Second, we only focused on assessment of criterion B (i.e. maladaptive trait domains). Although studies have highlighted a great overlap between criteria A and B (Zimmermann et al., Reference Zimmermann, Böhnke, Eschstruth, Mathews, Wenzel and Leising2015), assessment of criterion A could have helped to determine more general impairments in personality functioning, which are supposed to underlie all types of PDs (Morey et al., Reference Morey, Berghuis, Bender, Verheul, Krueger and Skodol2011). Third, our sample size may have been too small to detect differences between CBT and ST or to inform personalized treatment allocation choices, so even larger sample sizes with at least 300 participants per arm are needed in future research (Luedtke, Sadikova, & Kessler, Reference Luedtke, Sadikova and Kessler2019). Fourth, treatment effectiveness was evaluated based on BDI-II and PID-5-FBF scores at the end of treatment. Yet, previous research has highlighted the importance of including other outcomes (e.g. social functioning) to assess the potential impact of personality pathology and follow-up assessments (e.g. at 6-month post-intervention) to measure more enduring treatment effects (Newton-Howes, Mulder, Ellis, Boden, & Joyce, Reference Newton-Howes, Mulder, Ellis, Boden and Joyce2018), which should be addressed in future trials. Fifth, we were unable to control our analyses for medications and concomitant treatments, which could have influenced results from LCS models. Finally, it may be valuable to include a wait-list control arm in future studies to test if changes in personality pathology were not simply due to regression to the mean but rather a consequence of treatment.

Conclusion

Our study contributes to a better understanding of the effects of personality pathology on treatment outcomes of depressed patients. Contrary to clinical experiences, personality pathology did not negatively impact treatment outcome (i.e. depressive symptomatology) of depressed patients or vice versa. Additionally, maladaptive traits showed a substantial decrease after an intensive, yet relatively brief clinical intervention, which was irrespective of the psychotherapeutic treatment type. We also observed co-occurrences between depression and maladaptive trait domains at pre-treatment and between their respective changes over the course of treatment, which suggests that either a third variable affects both changes or reciprocal, or more dynamic processes of changes in maladaptive trait domains and depression occurred. As such, determination of the mechanisms linking the development of both personality pathology and depressive symptoms, as well as their changes will likely shed further light on the underlying causes, which could open up the possibility of new prevention and treatment targets.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291722001209.

Financial support

This research was funded by the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

All data collected were anonymous and the study was conducted following the ethical principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2008.