The World Health Organisation reported that in 2016, globally, 1·9 billion adults were overweight, of whom, 650 million had obesity(1). They also reported that in 2016 there were 41 million children under 5 and 340 million aged 5–19 years with overweight or obesity(1). Obesity and overweight are associated with a plethora of co-morbidities including cardiovascular disease(Reference Ortega, Lavie and Blair2), type 2 diabetes(Reference Mokdad, Ford and Bowman3) and some cancers(Reference Font-Burgada, Sun and Karin4). Given this, research into understanding obesity with a view to developing efficacious interventions is of high priority(Reference Ells, Demaio and Farpour-Lambert5).

The factors affecting the incidence of obesity are complex and multifactorial(6). One such factor that has garnered considerable interest is the relationship between ‘neighbourhood’ food environments and obesity(Reference Lake7). The overarching hypothesis is that the greater the number of food outlets that provide energy-dense low nutrient food, the greater the likelihood of the local population being overweight or obese. Some studies have provided evidence in support of this hypothesis(Reference Morland and Evenson8). However, overall evidence has been mixed with studies showing contradictory findings(Reference Bader, Schwartz-Soicher and Jack9) or failing to find any significant associations between individual food outlet availability and obesity(Reference Shier, An and Sturm10). Indeed, a systematic review of studies examining the relationship between the food environment and obesity showed that most associations between these factors were null(Reference Cobb, Appel and Franco11). However, the authors of this review did highlight some ‘noteworthy patterns’ between supermarket availability and obesity (negative association) and fast food availability and obesity (positive association).

In order to make sense of these mixed findings, it is likely that there is a need for studies that account for the potential nuances of the relationship between obesity and the food environment. For example, how are individuals using these outlets that are available to them and might this explain why their availability does not consistently predict obesity in the local area(Reference Cobb, Appel and Franco11). Penney et al.(Reference Penney, Almiron-Roig and Shearer12) make a similar point, suggesting that the external eating environment requires more specific investigations with a particular focus on ‘how people and environments interact’. Notably, Penney et al.(Reference Penney, Almiron-Roig and Shearer12) highlight the ‘model of community nutrition environments’(Reference Glanz, Sallis and Saelens13) as a useful starting point for investigations on this topic. The model was specifically developed to understand environments that provide opportunities for people to eat outside of the home. It indicates that policy, environmental (including the information environment) and individual-level variables interact in order to influence behaviour (eating patterns). Of particular relevance is the suggestion that individual-level variables, namely sociodemographic, psychosocial factors and the perceived nutrition environment, may mediate the relationship between the environmental variables and behaviour (eating patterns).

One approach to investigate the relationships between the factors outlined in the model of community nutrition environments(Reference Glanz, Sallis and Saelens13), and notably suggested by Cobb et al.(Reference Cobb, Appel and Franco11), is to gain a rich and nuanced understanding of consumers’ use of particular food retail outlets using qualitative methodologies. In a recent example, Blow et al.(Reference Blow, Patel and Davies14) conducted interviews with adults regarding their use of takeaway food outlets. They highlighted the importance of a number of variables that affected how individuals interacted with hot food takeaway outlets, including social factors (e.g. opportunity to bond with others), personal factors (e.g. values around importance of healthy eating) and resources (e.g. lacking time for cooking). This kind of understanding is important because it can help to evidence a more complex relationship between the local food environment and obesity and inform potential interventions targeting this relationship.

Another type of retail food outlet, the dessert-only restaurant, has grown in prominence in the local UK food environment; the most recent UK business report from the Local Data Company(15) indicated that whilst leisure sectors suffered the highest overall closure rates in 2018, dessert-only restaurant franchises displayed growth. This placed dessert-only retail food outlets in the top ten growing retail categories(15). Whilst establishments such as ice cream parlours and cafes serving cake have long existed, ‘dessert-bars’ follow a unique format that likens them more to formal restaurants (but without the main courses). They are also characterised by somewhat exaggerated features that set them apart, such as very large portion sizes, complicated recipes, high-quality ingredients and an extensive menu. Such outlets are also present in the USA and Europe. In addition, the growing ubiquity of dessert-only restaurants on the UK high street has attracted the attention of the media, with some documenting this trend(Reference Naylor16) and some demonising it(Reference Blake17). Yet, there is little formal research on the topic to inform a position, public health or otherwise.

Therefore, the aim of the current study was to gain a richer understanding of adults’ use of ‘dessert-only’ restaurants. Given the novelty of our research question, a mixed methods study was undertaken with a primary focus on a data-driven qualitative approach(Reference Braun and Clarke18,Reference Braun and Clarke19) and a secondary focus on quantitative factors that can provide additional context (e.g. demographic factors and information about visits to dessert-only restaurants). We used an online questionnaire to present open-response and closed-response questions to participants. Open questions allowed for qualitative textual data to be collected, which explored how and why dessert-only food outlets are visited. Closed (quantitative) questions were used to collect participant demographic and usage information (including prior use of a dessert-only restaurant).

Method

Participants

An initial 388 responses were recorded, 203 of which exceeded 98 % completion and were included in the final data analysis. This sample size exceeded the suggested minimum by Braun & Clarke(Reference Braun and Clarke19) of 80–100 respondents for a qualitative questionnaire study. The number of responses was monitored at regular intervals following the study start date, and the study was stopped at the earliest opportunity after the minimum number of responses had been collected. We note that this well exceeded the minimum due to the rapid nature of our online convenience sampling strategy. The sample consisted of 151 females and forty-seven males. The remaining four participants preferred to describe their own gender identity with two responding ‘female’, one responding ‘male’ and one response that suggested a misunderstanding of the question. One participant chose not to disclose their gender. The mean age of the participants was 33·5 years old (sd = 14·2).

Participants were recruited online on social media (via authors’ personal and institutional accounts) and the internal student participant pool at Swansea University. Participants recruited through the participant pool were offered one ‘credit’ on this system (that can then be redeemed within the system for students’ own study recruitment), and all other participants were offered the opportunity to be entered into a prize draw for a £10 Amazon gift voucher. Participants were reassured that their anonymity would remain if they chose to enter because their personal information (email address/student number) was unlinked from their data. The participants were told that the aim of the study was to investigate how people use dessert-only restaurants. The consent form advised those with either a current or previously diagnosed eating disorder and those under the age of 18 years old to refrain from participation. Ethical approval was granted by Swansea University Department of Psychology Research Ethics Committee.

Measures

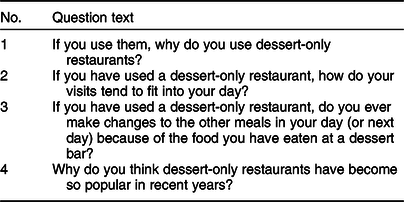

Open-ended questions explored the overall context of adults’ use of dessert-only restaurants and opinion regarding their popularity in general. These questions were broadly guided by the model of community nutrition environments(Reference Glanz, Sallis and Saelens13) with questions attempting to guide participants to think about individual-level variables (question 1) and behaviour – eating patterns (questions 2 and 3). As well as broader influences within the model including policy, environmental and informational variables (question 4). Due to the nature of our online convenience sampling approach, we did not design questions to target any particular individuals or topics that might be pertinent to a particular participant group. We also acknowledge that our questions were relatively structured given the novelty of our research area, this is because the online questionnaire methodology does not give the researchers an opportunity to clarify, guide or probe responses from participants. Therefore, questions must be comprehensive from the outset. Full question text is shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Question text for open-ended questions

Closed-ended questions were used to collect demographic information (gender, age, height and weight) and basic dessert restaurant usage information (frequency of visits, duration of a typical visit and use of takeaway facility).

Procedure

Participants took part in the study by clicking on an anonymous questionnaire (Qualtrics) link posted online (see details of recruitment strategy above). Once the link had been clicked, participants were provided with an information screen followed by an informed consent screen. Following the provision of informed consent, participants were asked to provide demographic information (age, gender, height and weight) and responses to the other closed-ended questions and the open-ended questions. Once completed, participants were given the opportunity to provide their email address for entry into the prize draw and were then debriefed.

Data analysis

Responses to the open-ended questions provided a qualitative dataset that was analysed using inductive thematic analysis(Reference Braun and Clarke18). Though, as recommended by Braun & Clarke(Reference Braun and Clarke19), we acknowledge that our approach is influenced by our perspective as psychologists with an interest in obesity.

Two researchers (TR and PW) conducted the thematic analyses independently and then compared results for agreement (investigator triangulation)(Reference Denzin20,Reference Thurmond21) . Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved by the researchers in the first instance; otherwise, a third researcher (LW) was consulted. Responses to open questions were read repeatedly, and recurring patterns were identified and coded. Codes were grouped into overarching themes and sub-themes. The original text responses were continuously referred to during theme formation.

Finally, self-reported height and weight were used to calculate BMI for each participant.

Results

Participant characteristics

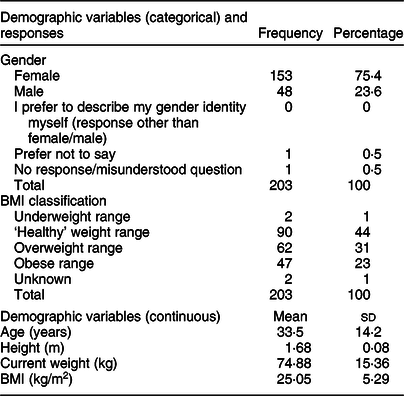

Demographic information collected included age, gender, height and weight, with the latter used to calculate participant BMI (see Table 2).

Table 2 Demographic variables that were categorical (gender and BMI range) are shown with frequency and percentage of total and demographic variables that were continuous (age, height, current weight and BMI) are shown with mean and sd

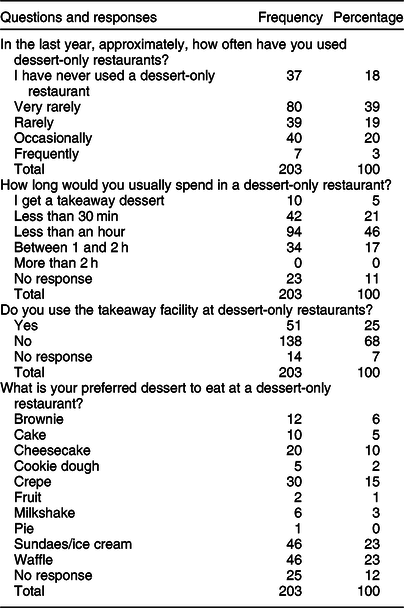

Quantitative information about the nature of visits to dessert-only restaurants was collected including frequency of visits, duration of visits and use of takeaway facilities (see Table 3). Notably, 82 % had visited a dessert-only restaurant at least once. Those participants who had never visited a dessert-only restaurant were retained for the study but did not respond to open-ended questions about their own reasons for visiting (some left the question blank, some wrote ‘not applicable’ or similar) and only responded to the open-ended question asking why they thought that such outlets might be popular.

Table 3 Frequency and percentage of responses to quantitative questions assessing aspects of dessert-only restaurant usage including frequency of use, duration of visit, preferred dessert and use of takeaway facilities

Thematic analysis of open-ended questions

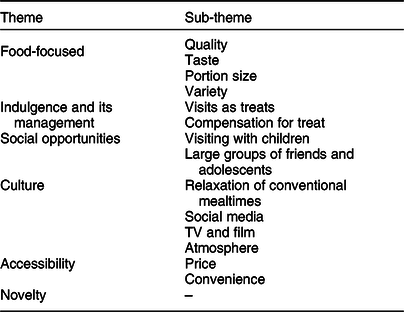

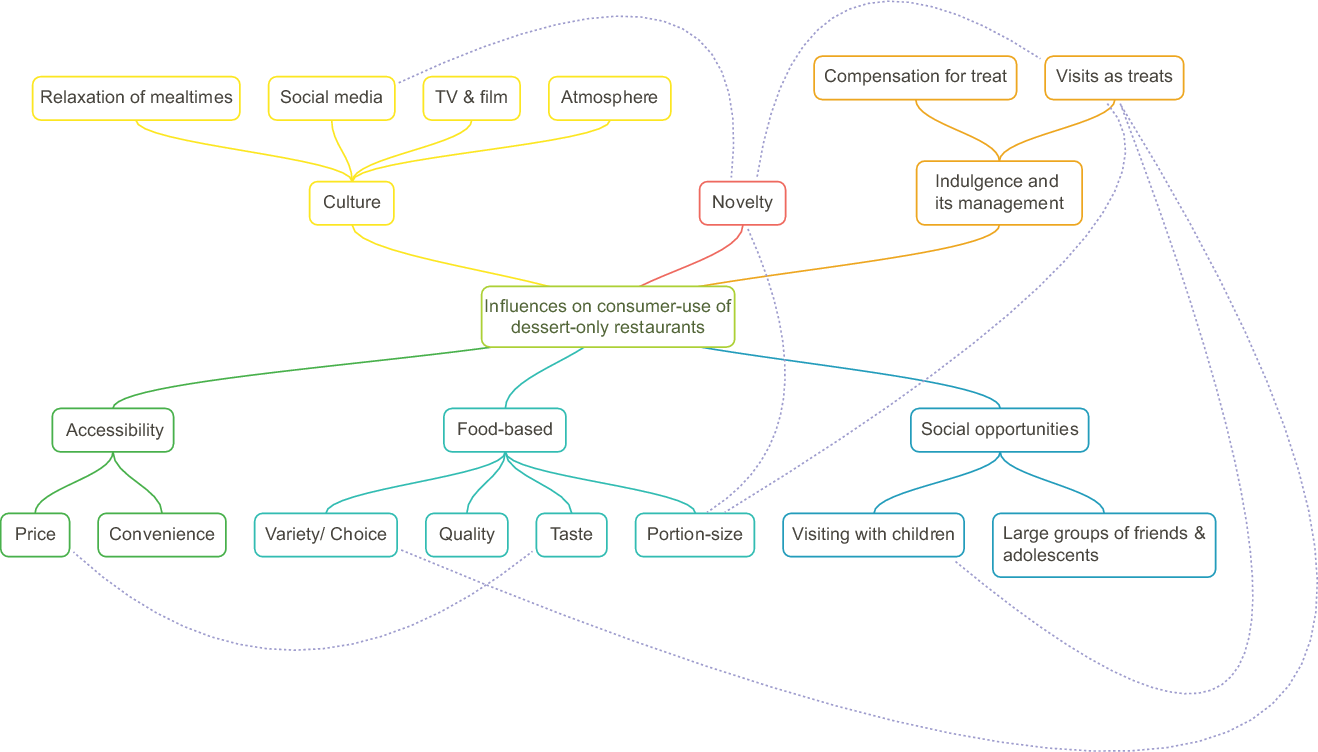

Major themes and sub-themes were identified (Table 4), and interconnections were explored within a thematic map (Fig. 1).

Table 4 Themes and sub-themes

Fig. 1 Thematic map showing themes, sub-themes and interconnections between them. Quotes associated with each interconnection can be found in the supplementary information file. The figure was created using MindNode software

Theme 1: food focused

Many of our participants suggested that features of the foods available to them at a dessert-only restaurant were why they visited and why they thought such outlets were popular. We explore these ideas under four sub-themes below (1) taste of desserts, (2) quality of desserts, (3) portion size of dishes and (4) the variety on offer.

Sub-theme: taste

Many of our participants mentioned the taste of the food provided at a dessert-only restaurant as a reason for their visit, some simply stating ‘Nice taste’ (F, 39 years old (yo)) or ‘Because desserts taste nice.’ (M, 19 yo). Other participants said that they thought that desert-only restaurants are popular because the foods are tastier than elsewhere, particularly because they are dessert based, ‘A lot of food is so bland these days and desserts are still tasty’ (M, 50 yo) and ‘Desserts are a more tasty option to regular meals’ (M, 22 yo). Other participants mentioned their popularity in terms of individual’s taste preferences, with particular reference to sweet taste, being met by the food offered at a dessert-only restaurant, ‘People’s taste’s are changing they like sweet things’ (F, 74 yo) and ‘Everyone loves sweet stuff don’t they?’ (F, 28 yo).

Sub-theme: quality

Participants also referred to the food provided by dessert-only restaurants in terms of its quality when asked why they visited, ‘better quality desserts’ (F, 20 yo) and one participant suggested that this quality was because of the focus of these outlets on desserts, ‘because they specify (sic) in desserts, making it better quality’ (F, 20 yo).

Sub-theme: portion size

Many of our participants said that the reason they visited a dessert-only restaurant was for the larger portion sizes that were available by comparison with other restaurants, ‘I enjoy having a dessert as a treat and dessert-only restaurants usually have a bigger portion size than a dessert from a normal restaurant’ (F, 21 yo). Some participants also suggested that this was a reason why they were popular, responding to this question saying, ‘Big portions’ (F, 30 yo) and ‘Over sized portions, sweet treats’ (F, 33 yo). Another participant offered greater elaboration in answer to the same question by benchmarking the size of dessert against a regular main course, ‘When you don’t want a main meal because you favour sweet food. You can get a meal size dessert rather than a small dessert with a main meal at a restaurant serving different courses’ (F, 60 yo).

Sub-theme: variety/choice of desserts

Many participants suggested a reason why they visited a dessert-only restaurant was the ‘wide variety of choice’ (F, 24 yo). Indeed, a key comparison was with the variety available at a regular restaurant, one participant suggested that the reason that they visited a dessert-only restaurant was the ‘Variety of different deserts [sic] they don’t usually do in all restaurants’ (F, 20 yo) and another participant offered a similar reason ‘There’s also lots of choice of dessert, unlike most restaurants’ (F, 21 yo). Our participants also mentioned choice and variety when asked why they thought that dessert restaurants were popular, echoing the comparison with regular restaurants mentioned, ‘Because of the range of products available to you that you cant [sic] usually get when you go to a conventional restaurant. For example, not many convential [sic] restaurant’s will offer such desserts as waffles topped with your favourite chocolate…’ (M, 24 yo). One participant also mentioned that they may be popular because of the nature of choice available, ‘The choice of desserts they serve and also they serve different desserts from anouther [sic] country’ (declined to provide gender, 22 yo). In addition, a few participants highlighted that they visited for a ‘dessert that I wouldn’t usually make for myself’ (F, 22 yo) and that dessert-only restaurants are popular ‘As you can’t really make them easily at home’ (F, 27 yo).

Theme 2: a treat and its management

Participants frequently described visits to dessert-only food retail outlets in terms of a ‘treat’ and described ways that they justified or compensated for that treat in terms of both physical activity and eating behaviour. This theme is explored below under two sub-themes, first, visits as treats, and second, compensation for treat.

Sub-theme: visits as treats

The idea of a visit to a dessert restaurant as a ‘treat’ was ubiquitous across responses from our participants. When asked how their visits might fit into their day, a key theme was as a treat, for example, it might be a treat following another activity ‘After the cinema for a treat with the kids’ (F, 31 yo) or as part of a broader treat ‘As part of a shopping trip treat’ (F, 48 yo). When asked why they use dessert-only restaurant, ‘As a treat’ was a phrase often repeated. Some participants elaborated suggesting that a visit was ‘My children’s choice for a treat’ (M, 38 yo) and ‘Me and my friends go for a treat’ (F, 18 yo). More broadly participants recognised people’s desire for a treat as a reason why dessert-only restaurants are popular, ‘Sometimes people just want a treat and not a meal as well’ (F, 30 yo) and ‘People like to indulge. And it feels naughty and decadent’ (F, 49 yo).

Sub-theme: compensation for treat

Whilst a large proportion (42 %) of our participants simply said ‘No’ when asked if they had ever made changes to other meals in response to a visit to a dessert-restaurant, many of them described doing so when asked how a visit to a dessert-restaurant fitted into their day. Many participants said that they had ‘dessert instead of a meal’, one participant described in more detail, ‘Normally would have a dessert instead of a meal in the evenings’ (F, 18 yo) whilst other participants described a slightly different approach ‘I’d have something small to eat like a sandwich or wrap’ (F, 20 yo) and ‘Usually have a small meal followed by the dessert’ (F, 20 yo).

For those participants who responded to the question regarding making changes to other meals in response to their visit to a dessert-only restaurant, the approach of replacing a meal with the dessert and/or modifying another meal recurred, ‘I will have dessert instead of my evening meal and probably not have breakfast the next day either’ (F, 21 yo). Another participant explained that they engaged in this kind of behaviour because they felt guilty following their visit, ‘yes, if I have eaten desserts usually try to eat healthier day after because I feel guilty for the bad choices’ (F, 21 yo).

Participants also made reference to physical activity in responses. When asked about making changes to meals in response to a visit, one participant said that not only would they make a change to their food intake but also their physical activity, ‘Sometimes I will eat well the following day and make sure I go to the gym more frequently that week’ (F, 20 yo). Some participants also mentioned physical activity as part of their response to how their visit fitted into their day, ‘As part of a day out, after a long walk’ (F, 56 yo) and for another, ‘once as a treat after training’ (M, 22 yo).

Theme 3: social opportunities

Many participants described dessert-only restaurants in terms of the social opportunities that they provide. In particular, social opportunities for families with young children were mentioned and opportunities for larger groups of friends, with particular reference adolescents. We explore these two themes below.

Sub-theme: visiting with children

When asked about why they visited a dessert-only restaurant, a group of participants said their visits focused around a visit for the enjoyment of children, ‘Fun for the children’ (F, 25 yo) and a treat for children ‘My children’s choice for a treat’ (M, 38 yo) and family ‘We use these places as family treat, after a day out’ (F, 29 yo). Other participants mentioned children’s preferences for desserts as a reason why dessert-only restaurants might be popular, ‘Children love sweet things and would probably prefer to get a cake or an ice cream rather than a meal.’ (F, 21 yo) Finally, one participant mentioned a social pressure as the reason for a visit ‘Just so the kids can say they have been!’ (F, 31 yo).

Sub-theme: visiting with friends

Many of our participants mentioned that the reason that they visited was to socialise with friends, for example, comments such as, ‘To catch up with friends…’ (F, 44 yo). On the one hand, some participants mentioned that the format of a dessert restaurant made them popular because they facilitated social interaction, ‘If you just want a dessert but whoever you go to a restaurant with wants a full meal it might be awkward. With dessert restaurants everyone can just grab a dessert without having to feel like they need to eat a meal beforehand’ (M, 21 yo), but on the other hand, some participants found that social influence was a reason for visiting ‘Other people like them so might as well go with’ (M, 22 yo), ‘Usually other people I’m with want to go in’ (F, 20 yo). Finally, one participant suggested that dessert-only restaurants were popular because they provide an alcohol-free environment, ‘somewhere for kids to go without the pressure to consume alcohol’ (F, 61 yo).

Theme 4: culture

Participants discussed a number of broader cultural influences that motivated their use of dessert-only restaurants or that they recognised as reasons why they might be popular. These are explored in the following sub-themes: relaxation of conventional mealtimes, social media, TV and film and atmosphere.

Sub-theme: Relaxation of mealtimes

Many of the participants discussed the rising popularity of dessert-only restaurants because of a relaxation of mealtime norms, suggesting that there are ‘less conventional rules on eating meals’ (M, 24 yo) and, in what might be considered a slightly facetious response, one participant mentioned the notion of a ‘real’ meal and a reduction in pressure to follow this, ‘People have seen sense and don’t make you eat “real” meals anymore’ (F, 27 yo).

Sub-theme: social media

A key reason why participants thought that dessert-only restaurants were popular was social media. Some participants simply wrote ‘Instagram’ (F, 24 yo) or ‘Social Media’ (F, 18 yo) in answer to our question. Whilst others elaborated and specified how social media and dessert restaurants were tied together through feeling like social media exerts a pressure to visit, ‘Social media, they are often seen on Instagram and Snapchat so people feel they should go too’ (F, 20 yo), formal advertising on social media ‘Because of social media advertisement’ (F, 20 yo) and the desire to share the experience, ‘they look quite good (the food and the decor)so good for people who like to post on social media’ (F, 26 yo).

Sub-theme: TV and film

Some participants mentioned an influence of TV and film when asked why they thought that dessert-only restaurants were popular. For one participant, the influence of TV was about people emulating what they see, ‘These have been made popular from being TV programme and people like doing what their favourite stars are doing’ (F, 48 yo), for another participant the influence of television was about the foods that are seen, ‘Increase in cooking programmes on TV and social media raising awareness/desire for more extravagant desserts’ (F, 23 yo) and for another participant there was a broader cultural influence and the suggestion of an opportunity to socialise, ‘We are becoming more Americanised. We see them in movies as a good place to socialise’ (F, 24 yo).

Sub-theme: atmosphere

Some of our participants reported that the atmosphere and environment of a dessert-only restaurant was a reason why they are popular. In particular, by comparison to regular restaurants, ‘A more relaxed feel than a busy main meal restaurant’ (F, 44 yo) and ‘… and more relaxed than a formal restaurant but nicer surroundings than [popular fast food restaurant]’ (F, 26 yo).

Theme 4: accessibility

Participants tended to mention two aspects of accessibility, favourable prices and convenience, as reasons why they used dessert-only restaurants and why they might be popular more generally. These two sub-themes are explored below.

Sub-theme: price

When participants were asked why they visited a dessert restaurant, price and the idea of value for money were mentioned, specifically by comparison with other restaurants, ‘Because the desserts taste amazing and they are worth your money more than in a restaurant’ (F, 20 yo) and ‘… cheaper than a full meal at a restaurant, easy and quick’ (F, 26 yo). This theme recurred when participants were asked why they thought that dessert-only restaurants were popular, aside from simply stating ‘cheap’ as part of a list of reasons, some participants specifically mentioned that one way that value was achieved was because there is no need to purchase a main meal as well as a dessert, ‘Because it’s a treat and keeps costs down by providing dessert only’ (F, 48 yo). Furthermore, one participant suggested that this might allow people to eat out, ‘Cheap way to eat out, all family can enjoy’ (F, 41 yo) and that this might be particularly the case for young people, ‘Cheap for teenagers and a place to meet up’ (F, 39 yo).

Sub-theme: convenience

Many participants mentioned that they found dessert-only restaurants convenient to visit. As a reason for why they visit a dessert restaurant, one participant mentioned the convenience of the location, simply saying that they ‘have one close to where they live’ (F, 57 yo), whilst another participant talked about the benefit of no waiting times, ‘Sometimes they’re more convenient to use rather than a normal restaurant, as with normal restaurants there are a lot of waiting times. Whereas a dessert restaurant usually there are seats readily available’ (F, 22 yo) and other participants mentioned the ‘Quicker service’ (F, 51 yo). This latter point was echoed by another participant responding to why they thought that dessert restaurants are popular, ‘Quick service, cheaper & easily accessible’ (F, 41 yo). Indeed, one participant highlighted the importance of convenience by suggesting that the reason they did not visit often was because of a lack of convenience, ‘…we don’t frequently visit probably just because they aren’t conveniently situated near anywhere we usually go’ (F, 27 yo).

Theme 5: novelty

Many of our participants mentioned the importance of novelty as a reason for visiting a dessert-only restaurant, one participant said that it was a ‘Novelty and unique experience’ (F, 21 yo), while another participant made a direct comparison with other restaurants, ‘Something different compared to other restaurants’ (F, 20 yo) and there is a desire to ‘To try it out’ (M, 25yo). When asked why they thought dessert-only restaurants were popular, one participant discussed the appeal of something new and suggested it was a trend for a particular age group, ‘Prior to now, we didn’t have access to places which focus solely on desserts only, therefore the exclusively of having that option became very appealing to start a trend amongst millenniums mainly’ (F, 21 yo). Another participant also suggested that visits represented a part of a trend, ‘New trend, something different, reminds me of American foods’ (F, 20 yo) whilst another also suggested that the novelty appealed to a younger age group, ‘It’s a new concept and I feel appeals to younger people’ (F, 53 yo).

Discussion

The aim of this mixed methods study was to understand the influences on consumer use of dessert-only restaurants. As a result of our qualitative analyses, we identified six broad themes and associated sub-themes. Participants described the importance of food-specific factors, indulgence and its management, social opportunities, culture, accessibility and novelty.

These analyses were supplemented by quantitative data about participants’ frequency and duration of visit, use of takeaway facilities and preferred dish. Notably, this showed that the majority of participants visited a dessert-only restaurant either very rarely, rarely or occasionally and tended to spend less than an hour on the premises.

A visit to a dessert-only restaurant as a treat was a key theme within our dataset and participants mentioned the notion of a treat in conjunction with the portion sizes served, the variety of foods available and novelty value (which in turn was also mentioned in conjunction with portion size). This focus on a visit as a treat may be a feature that is distinct to dessert-only food retail outlets by comparison with other types of outlets, such as ‘hot food takeaways’. Whilst Blow et al.(Reference Blow, Patel and Davies14) mention the notion of an ‘indulgence’ in the context of using takeaway outlets, inferred because participants discussed engaging in compensatory behaviours suggesting some health concern, they also note an absence in their data of a desire to consume unhealthy foods. Indeed, there lacks an explicit theme on consumption as a treat with respect to takeaway food consumption(Reference Blow, Patel and Davies14). Broadly, the potential differential use of food retail outlets, based on type suggested here, supports the model of community nutrition environments(Reference Glanz, Sallis and Saelens13) which includes types of food outlets (under the category of community nutrition environments) as a potential direct and indirect influence on eating patterns. Though this model highlights ‘stores’ compared with ‘restaurants’ and it may be appropriate to include the influence of different types of restaurants as well.

Whilst the focus on a visit as a treat in our data seemed to contrast with findings relating to hot food takeaway consumption in the study by Blow et al.(Reference Blow, Patel and Davies14), this finding is more consistent with McGuffin et al.(Reference McGuffin, Price and McCaffrey22) who found that ‘a treat’ was a key reason (and dominant theme) for why families chose to eat outside of the home. Indeed, we observed that those participants who mentioned that children were the reason that they visited a dessert-only restaurant (under the social opportunities theme) often discussed this in terms of a treat. This highlights a visit to a dessert-only restaurant in the context of a family activity and a feature of a child’s food environment and suggests that this setting may merit attention in the context of childhood obesity interventions targeting the external food environment(Reference Penney, Almiron-Roig and Shearer12).

Alongside discussion of a visit to a dessert-only restaurant as a treat, there were clear descriptions from participants of the active management of their food consumption. Again, themes that were unique to the specific dessert-only context were observed, the purposeful replacement/ skipping of a main meal with a large dessert or compensation with either dietary restriction or exercise. Notably, the strategies mentioned here contrasted with the types of ‘damage control’ reported by Blow et al.(Reference Blow, Patel and Davies14) regarding hot food takeaway consumption – in their study they found that participants would choose the least unhealthy option and order smaller dishes. The strategies mentioned in the current study are more consistent with those reported in a recent study investigating consumer’s everyday strategies for the everyday management of tempting foods(Reference Gatzemeier, Price and Wilkinson23).

Interestingly, there seemed to be some convergence between the eating patterns and behaviours mentioned as compensatory (e.g. replacing a main meal with a dessert) and those that are facilitated by a relaxation of mealtimes. The latter theme highlighted participants’ view that one of the reasons why dessert-only restaurants are popular is because of ‘less conventional rules on eating meals’ and that these outlets facilitate consuming a dessert without the need to consume a main meal first. This supports the view that ‘social norms’ (an unspoken rule book that guides ideas about what is appropriate behaviour) are an important driver of eating behaviour(Reference Higgs24). In this context, it seems to be suggested that it is socially acceptable to consume a dessert as a main meal and we note that the practicalities of consuming a dessert without a main meal are facilitated by the existence and format of dessert-only restaurants (e.g. the desserts provided are large enough to replace a main meal; see ‘portion-size’ sub-theme). This may also enable meal replacement as a compensatory approach. One possibility is that historic changes in conventions around meals (see Meiselman(Reference Meiselman25) for relevant discussion of the ‘meal’ from a historic perspective) have influenced the popularity of dessert-only restaurants and the existence of dessert-only restaurants have influenced conventions around meals.

As in other studies concerned with the out of home food environment(Reference Janssen, Davies and Richardson26), our participants suggested that dessert-only restaurants offered an eating opportunity that was attractive because of convenience and affordable pricing. The importance of this influence on food choice and eating behaviour is consistent with findings on takeaway consumption(Reference Blow, Patel and Davies14) and the model of community nutrition environments(Reference Glanz, Sallis and Saelens13) which includes both convenience (part of the model’s ‘community nutrition environment’ section) and price (part of the model’s ‘consumer nutrition environment’ section) as direct and indirect influences on eating patterns. However, with respect to price, one notable factor that may be unique to the context of dessert-only restaurants is that the cost of a visit was made more accessible because you do not have to purchase a main course in addition to a dessert.

Overall the importance of convenience as an influence on visits to a dessert-only restaurant shown in our dataset support the assumption that underpins why neighbourhood food environments may be an important influence on both adult and childhood obesity (for more detail see Introduction section). However, our dataset may also offer some insight into why the mere presence of outlets offering high energy density foods may not consistently predict local incidence of overweight and obesity(Reference Cobb, Appel and Franco11). First, our quantitative results showed that the overwhelming majority of our sample reported only visiting such outlets very rarely, rarely and occasionally. Moreover, the importance in our dataset of a visit as a ‘treat’ (which as a term implies an infrequent but pleasurable occurrence) seems to support the notion that whilst these outlets may be an everyday sight in our local food environments, a visit may not be an everyday event. One possibility is that this limits the influence of outlet presence on overweight and obesity.

Consistent with the model of community nutrition environments(Reference Glanz, Sallis and Saelens13), an influence of the ‘information environment’ including media and advertising was evident. In particular, we observed an emphasis on social media and the importance of (1) seeing posts on social media as a reason to visit a dessert-only restaurant and (2) the opportunity to ‘post’ on social media that a visit provided. This finding supports research by Holmberg, Chaplin, Hillman and Berg(Reference Holmberg, Chaplin and Hillman27) who showed that many adolescent users of social media were posting food items and the majority of these were high in calories and low in nutrients. A concern has been raised that these sorts of behaviours might be associated with the promotion of unhealthy relationships with food(Reference Rousseau28). Our data suggest that a nuanced approach is required because the context of social media posts (which may or may not be communicated in these posts) is that a visit is a treat. A treat can be part of an overall healthy diet when consumed ‘less often and in smaller amounts’(29), and evidence has suggested that strict restriction can have ironic effects(Reference Fisher and Birch30). Whilst recent work has highlighted a positive influence of healthy food posts on social media(Reference Mejova, Abbar and Haddadi31), in the case of posting dessert photographs, future research might explore the context of such social media posts and investigate a role for communicating the ‘treat’ context.

This work has a number of limitations, most notably, the questionnaire-based approach meant that participants could not be probed for elaboration on points in the way that would be possible in a focus group or interview. Therefore, many of our quotes are relatively short and lack nuance. A further limitation is the lack of information about participant ethnicity and socio-economic status. Future studies should consider including these measures in order to reflect the differential experiences of the external eating environment (including dessert-only restaurants) that people might experience. For example, Janssen et al.(Reference Janssen, Davies and Richardson26) found that both of these factors affected the determinants of out-of-home food consumption. Finally, this study collected information on frequency of visit; however, we note that participants may have differed in their interpretation of options such as ‘rare’ or ‘frequently’. A future study could use a less subjective measure, for example, ‘one visit a month’ or ‘one visit a year’.

Nevertheless, this is the first study of its kind to explore factors influencing dessert-only retail food outlet usage and included a large sample with a wide age and BMI range. This adds to a growing literature on the factors influencing people’s use of different types of food outlets that exist in the neighbourhood food environment. This work suggests that, despite some media opinion, this type of food retail outlet is being used somewhat judiciously by consumers; visits were infrequent for the majority of our participants, many participants referred to a visit as a ‘treat’ and many described managing their intake in response to an upcoming or previous visit. The status of a visit to a dessert-only restaurant as a ‘treat’ may limit the efficacy of potential public health interventions as a treat is by definition a departure from an overall approach (Blow et al.(Reference Blow, Patel and Davies14) make a similar point regarding treats and the provision of healthier alternative foods). A fruitful focus may be on the management of treats within the broader context of the diet as opposed to targeting the treat itself, this may be especially helpful for parents/ caregivers taking their children out for a treat to a dessert-only restaurant. This approach may also offer an opportunity to discuss compensatory behaviours and the nuance that exists between sensible ways to incorporate a treat into your broader diet and less healthy compensatory behaviours that may become a risk factor for eating psychopathology and distress(Reference Darby, Hay and Mond32). These types of insights must inform policy decisions around the management of food retail outlets in local environments, for example, the increasingly popular use of exclusion zones for particular types of outlets(Reference Keeble, Burgoine and White33). Taking into account how outlets are used may help to avoid failed approaches or potential unintended consequences.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank our anonymous reviewer and the associate editor for their constructive and helpful feedback that substantially improved this manuscript. Financial support: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: No conflict of interest is reported. Authorship: All authors contributed to the study design, T.R. and P.J.W. conducted data collection and all authors contributed to data analyses, manuscript drafting and manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Department of Psychology Research Ethics Committee at Swansea University. Digital informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020003146