The proportion of people in the global population who are overweight is increasing(Reference Ng, Fleming and Robinson1). Excess weight and juvenile obesity in particular are among the most serious public health problems currently faced in developed countries. The findings of a representative national study, the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS 2014–2017), showed that about 15 % of children and adolescents aged 3–17 years in Germany today are overweight, including a 6 % obesity rate(Reference Schienkiewitz, Brettschneider and Damerow2). Within just 20 years, the prevalence of overweight and obese adolescents has doubled or tripled, respectively(Reference Schienkiewitz, Brettschneider and Damerow2 , Reference Kurth and Schaffrath Rosario3).

By the late 1990s at the latest, our physical, economic, political and sociocultural environments had been recognized as important in the development of obesity(Reference Swinburn, Egger and Raza4). In this context, obesogenic environments are described as ‘the sum of influences that the surroundings, opportunities, or conditions of life have on promoting obesity’(Reference Swinburn, Egger and Raza4). Kremers et al. highlight that an individual’s energy balance is the decisive factor in the development of obesity and that both movement-related and nutrition-related environmental factors should always be considered equally in this context(Reference Kremers, de Bruijn and Visscher5). The latter are also referred to as nutrition or food environments(Reference Glanz, Sallis and Saelens6). Studies have proved at least a correlation between unfavourable food environments, sale of unhealthy foods or the density of fast-food establishments on the one hand and childhood weight status on the other(Reference Glanz, Sallis and Saelens6,Reference Wilsher, Harrison and Yamoah7) .

Restaurants are considered to be important food environments(Reference Valdivia Espino, Guerrero and Rhoads8,Reference Ayala, Castro and Pickrel9) . In Germany 62 % of all families eat out at least once per month, of which 14 % eat out once per week or more, and spend an average of €66 per month (as of 11 July 2018 this is equal to $US 77·32 or £58·41) on eating out(10,11) . More than two billion visits are recorded to full-service restaurants annually(12). These high visitor numbers mean that studying restaurants can potentially be an important, innovative approach to improving food environments(Reference Ayala, Castro and Pickrel9).

The range of foods available in restaurants is of particular relevance for children and adolescents. An evaluation of the nutritional quality of children’s meals at the fifty largest US restaurant chains showed that 99 % of 1662 children’s meal combinations were of poor nutritional quality(Reference Batada, Bruening and Marchlewicz13). In Japan, an evaluation of typical chain restaurants found that the majority of children’s meals contained inappropriate amounts of fat and salt. In total, only 16 % of all meals satisfied the national standards(Reference Uechi14). Similar results were also found in Australia, where an investigation of the nutritional composition of children’s meals in fast-food chains revealed high levels of saturated fat, sugar and sodium. Here too it was found that only 16–22 % of all meals satisfied nutritional criteria(Reference Wellard, Glasson and Chapman15). These and other studies show that restaurant foods are often higher in kilojoules and lower in nutritional quality than meals prepared at home, meaning that they usually contain higher amounts of total fats, saturated fats, sugar, cholesterol and sodium, while at the same time providing lower amounts of fibre and several vitamins and minerals such as iron, calcium and zinc(Reference Moran, Block and Goshev16–Reference Cornwell, Villamor and Mora-Plazas20).

Unlike in the USA, fast-food and chain restaurants play a much less influential role in Europe(21); in Germany, these types of restaurant make up only 24 % of total restaurant sales(22). Instead, the German market has traditionally been dominated by owner-operated restaurants, sometimes referred to as the individual food-service industry. Families in particular are generally more likely to go to such an independent, owner-operated full-service restaurant than to a chain for their lunchtime or evening meal.

The present study aimed to investigate the food environment for children in German full-service restaurants. This is the first time that the range of children’s meals available in German restaurants has been quantitatively described and qualitatively evaluated on the basis of a national sample.

Data and methodology

Defining the restaurant sample

The first step within the ‘Kids’ meals in Germany’ (KinG) study was to obtain a nationwide sample of restaurants using systematic quota sampling. Official tax records were used to calculate the quotas, i.e. the number of restaurants per federal state that needed to be included in the study, for a total sample size of 500 restaurants( 23). The relevant tax statistics for the last available year at the time that the sampling was done included the number of businesses listed under ‘Gastronomie’ (restaurants with and without accommodation in 2015) per federal state.

Following the calculation of the quotas, sampling was carried out between 1 June and 12 June 2017 using the online search engine Google. Searches were performed by entering a combination of keywords, one from a group of German terms for restaurant-style establishments where food is served (‘Restaurant’, ‘Gaststätte’, ‘Gasthof’) and one from a group of keywords typically used to denote children’s meals (‘Kinderkarte’, ‘Kindergerichte’, ‘kleinen Gäste’). In order to avoid a bias caused by user data or online advertising, the selection was carried out without logging in to a Google user account and without looking at any recommended links or paid advertisements. A random sampling process was then used to identify individual restaurants from the hit list and to eliminate any duplicates. Next, the website of each individual restaurant was visited to check that it satisfied the inclusion criteria described below. This process was repeated until the previously established quotas were reached. The last author was responsible for selecting the samples.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for restaurants and children’s menus

Identifying the restaurants

Our study aimed to gather data on the range of foods available in the typical situation whereby a family goes out to eat a main meal with one or more hungry children. For this reason, the sample included individual full-service restaurants with table service (‘sit-down restaurants’(Reference Saelens, Glanz and Sallis17)) which had an online menu that explicitly included a children’s menu. The section of the menu was always clearly identifiable, for example with headings such as ‘Children’s menu’, ‘Kids’ meals’ or ‘For our younger guests’. As families do not typically go to bakeries, snack bars or other self-service restaurants in the case described above and also because these types of establishments do not usually offer table service and separate children’s menus, these cases were excluded from the study. Furthermore, German industry statistics and official economic statistics do not classify these types of establishment as full-service restaurants(23). Chain restaurants, defined in Germany as restaurants with more than two branches, were excluded from the sample, because kids’ meals such as those typically served in chains like McDonald’s and Burger King have already been investigated in numerous recent studies(Reference McCrory, Harbaugh and Appeadu24). The identified menus, including the restaurant address, were archived in paper format and digitally as a PDF file.

Identifying the children’s menus within the restaurants’ menus

All children’s meals were identified and their specific description was transcribed in full, e.g. ID57_6 ‘Pizza with salami and olives’, ID 418_2 ‘Bratwurst with French fries and ketchup’. Starters and desserts (such as ‘Alphabet soup’ or ‘A scoop of chocolate ice cream with cream’) were not included if they were listed in the menu as a separate item with an individual price. Starters and desserts were included in the evaluation only if such components were included as part of a clearly defined meal (e.g. 286_2 ‘Breaded turkey escalope with vegetables and fries and an ice cream’).

Quantity and quality of the foods on offer

For each restaurant, a record was made of the number of children’s meals on the menu and the address and zip code of the restaurant. Storing address data allowed for a subsequent analysis at regional level. A note was also made indicating whether the restaurant offered any type of accommodation (e.g. hotels, motels or bed and breakfasts). In addition to this, descriptive information was also recorded such as whether an age limit for the children’s meals was indicated on the menu or if at least one vegetarian dish was offered. The survey did not record the so-called ‘bandit’s plate’ (an empty table setting for a child, allowing them to ‘steal’ food from other guests at the table), which is frequently offered in Germany and allows children to take menu items that they like to eat.

An evaluation of the individual meals was then conducted using the Quality Standards for Catering in Children’s Daycare Centers, published by the German Nutrition Society (DGE), and the Children’s Menu Assessment (CMA) score(Reference Krukowski, Eddings and Smith West25) as a general basis. The DGE publishes recommendations for lunchtime meals (out-of-home meals in kindergarten, daycare centres or schools), these cover both the design of the meal plan and the recommended ingredients and preparation methods(26 , 27). As the DGE quality standards currently represent the only recommendations for out-of-home meals in Germany, these were used in our study to derive aspects for the design and preparation of children’s menus in full-service restaurants. In total, eleven aspects concerning ingredients and preparation methods are classed as positive according to the DGE quality standards (see Table 1).

Table 1 Aspects investigated based on the German Nutrition Society (DGE) quality standards

Using this as a basis, we (including J.H.-K., a qualified dietitian) performed an assessment of both the composition of the menu and the nutritional quality of the ingredients and preparation methods used in the meals. Before the adapted quality criteria from the DGE were applied to the original data set, the inter-rater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0·901, 95 % CI 0·705, 0·967, P < 0·001) was tested for both investigators (S.S and L.R.).

Regional analyses

By using the individual restaurant addresses, it was possible to assign regional data to each location. These official data were taken from the German Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development and included information about the local population density, average age, proportion of foreigners, unemployment rates, child poverty rates, household income and tourism levels (number of overnight stays)(28).

Validating the database

In order to validate the database, a second nationwide sample was created to quantify how many restaurants do not make their menu available online (n 100). Finally, a third sample was investigated to test whether the restaurants without an online presence were different from the original study sample in terms of their outcome. This third sample was comprised exclusively of meals from restaurants that do not publish their menu online, but which fulfil all other inclusion criteria (n 50). In addition to this, other standard quality control measures (plausibility checks, double coding, checking extreme values) were carried out as well as a post hoc power analysis.

Statistical methods

The statistical analysis comprised a classic descriptive evaluation based on the number of restaurants and the meals on the menu. Mean and sd were calculated for the continuous variables. Percentage values were reported with corresponding 95 % CI. Associations between nominal variables were tested using χ 2 tests and between two continuous variables using Pearson’s correlation coefficients. All tests were two-sided and a predefined P value of ≤0·05 was considered significant. All analyses were conducted using the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0.0.

Results

Using the individual restaurant as the unit for analysis, the child-specific food environment in full-service restaurants in Germany can be described as follows. On average, every menu included 3·76 (sd 1·31) meals for children (Table 2). One in seven restaurants included details in their menu about the minimum and maximum ages for children to be able to order from their range of children’s meals (Table 2). Three-quarters of all restaurants offered at least one vegetarian meal for children on their menu. This was usually pasta with tomato sauce or French fries with ketchup.

Table 2 Characteristics of restaurants and children’s menus included in the ‘Kids’ meals in Germany’ (KinG) study, a nationwide sample of menus from German full-service restaurants in 2017 (1877 meals from 500 menus)

Table 2 also shows the options provided in the context of the DGE recommendations for menu design. Only one of the 500 restaurants included in the study used a graphical illustration to present the dishes; in this specific case, photographs were used. There were no cases where dishes that were recommended from a nutritional–physiological point of view, i.e. nutritionally balanced dishes, were visually highlighted in any way on the menus. In most cases, all dishes and their sides were clearly described. There were only a few individual cases, such as ‘hedgehog sausage’ (ID 492_3) and ‘Children’s dream’ (ID 426_1), where it was unclear what exactly would be served. Furthermore, the descriptions of meat dishes were so unclearly formulated in approximately seven out of ten menus that it was not possible to identify what kind of animal was used. A common example was the description ‘Kid’s escalope’ (‘Kinderschnitzel’), whereby it was unclear whether this referred to veal, pork, turkey or chicken escalope (see Table 2).

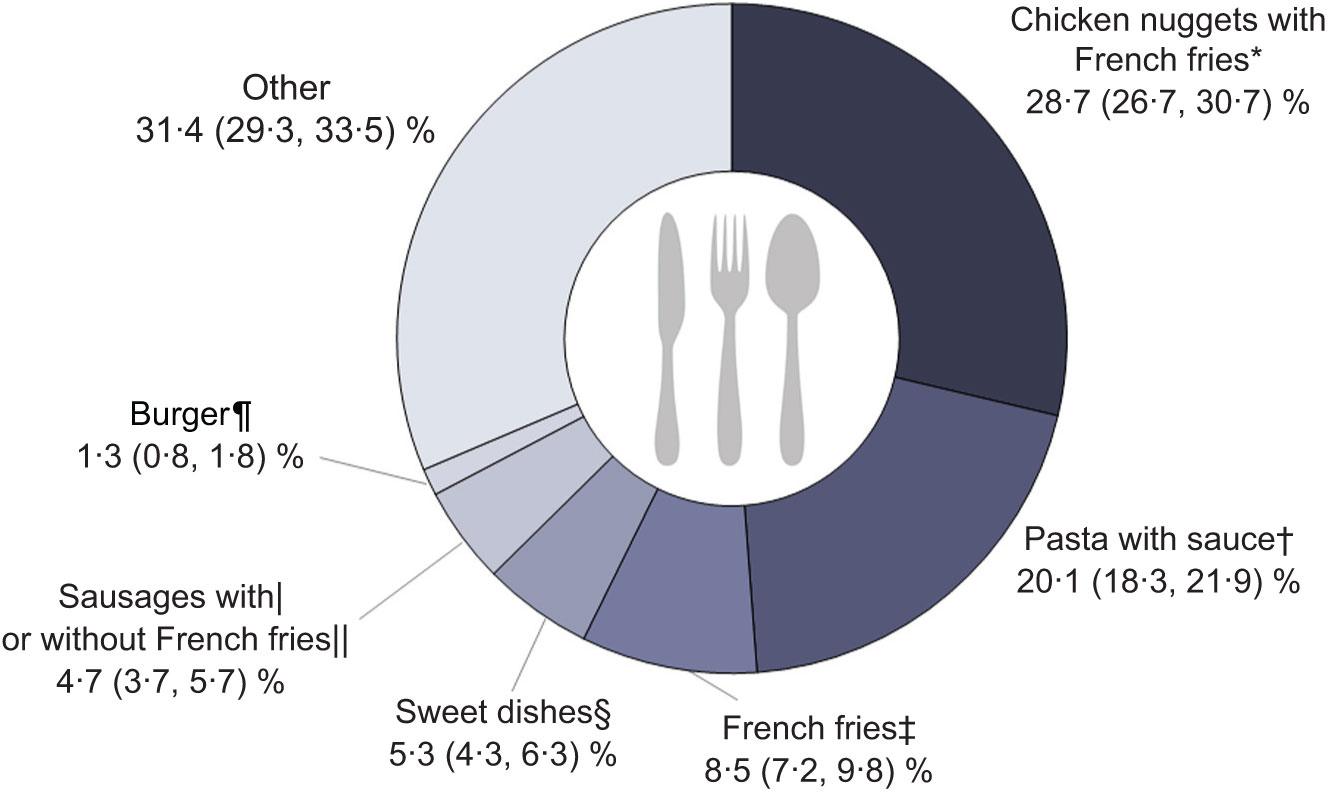

A total of 1877 meals were recorded from 500 menus. However, about 70 % of the meals were limited to six common dishes (Fig. 1). More than a quarter of all children’s meals consisted of a variant of chicken nuggets with French fries (29 % of all meals). This category also included variants of breaded meat in different shapes, which were usually deep-fried (also referred to as ‘chicken crossies’, ‘schnitzel sticks’, ‘chicken crispies’) and always served in combination with deep-fried potato products. One in five meals comprised pasta with sauce (e.g. cream sauce, ham and cream sauce, tomato sauce). The third most common meal offered to children was French fries as a meal on their own, without any other meat or vegetable component. French fries were also very common (45·7 %) as a side dish in the category ‘Other meals’. Overall, this meant that 54·2 % of the 1877 meals included French fries or another form of fried potatoes, e.g. potato twisters, potato wedges, fried potatoes, potato chips and potato spirals (see Fig. 1). Where fish was offered, this was almost always breaded fish sticks. Combined with a few individual cases of ‘breaded fish fillet’, these made up 7·7 % of all meals (n 144).

Fig. 1 The meals most commonly found in the restaurants included in the ‘Kids’ meals in Germany’ (KinG) study, a nationwide sample of menus from German full-service restaurants in 2017 (1877 meals from 500 menus). Values are percentages with 95 % CI in parentheses. *Also includes other variants of breaded lean meat in different shapes, which were usually deep-fried (also given names such as ‘chicken crossies’, ‘schnitzel sticks’, ‘chicken crispies’) and always served in combination with deep-fried potato products. †Includes lasagne. ‡French fries or any other form of fried potatoes (twisters, potato wedges, fried potatoes, potato chips, potato spirals) with or without ketchup, mayonnaise or another sauce and without any other side dish. §Semolina pudding, rice pudding, hash browns, etc., always served with a sweet side (e.g. nut-nougat spread, cream, chocolate sauce, jelly). ║Usually served with French fries or another form of fried potatoes (twisters, potato wedges, fried potatoes, potato chips, potato spirals). ¶With or without French fries

A nutritional evaluation of the foods available was carried out based on the DGE quality standards. A quarter of the meals on offer contained cereal products or potato products that had not been fried, usually these were offered as a side dish. There were no cases in which it was stated on the menu whether these were wholegrain products. A third of all meals were offered with vegetables or salad (Table 3), of which 12 % were meals with raw vegetables (including salad). Fruit, on the other hand, was rarely included as part of the meal.

Table 3 Assessment of the children’s menus, based on the quality standards set out by the German Nutrition Society, found in the ‘Kids’ meals in Germany’ (KinG) study, a nationwide sample of menus from German full-service restaurants in 2017 (1877 meals from 500 menus)

The type of oil used (e.g. olive oil, rapeseed oil or soyabean oil) was indicated in only one case. Our analyses also show that including a drink in the price of a meal is extremely unusual in Germany: a drink was included in the meal deal in only eleven cases. In ten of these cases, it was a soft drink and in one case it was mineral water (Table 3).

By calculating the number of fulfilled quality standards for catering for children as stipulated by the DGE, it can be seen that 23 % of all meals did not fulfil any of these criteria and 38 % satisfied only one criterion (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Number of fulfilled quality criteria, using the meal as the unit of analysis, found in the ‘Kids’ meals in Germany’ (KinG) study, a nationwide sample of menus from German full-service restaurants in 2017 (1877 meals from 500 menus). Quality criteria according to the recommendations made by the German Nutrition Society regarding food preparation and service for childcare facilities and schools

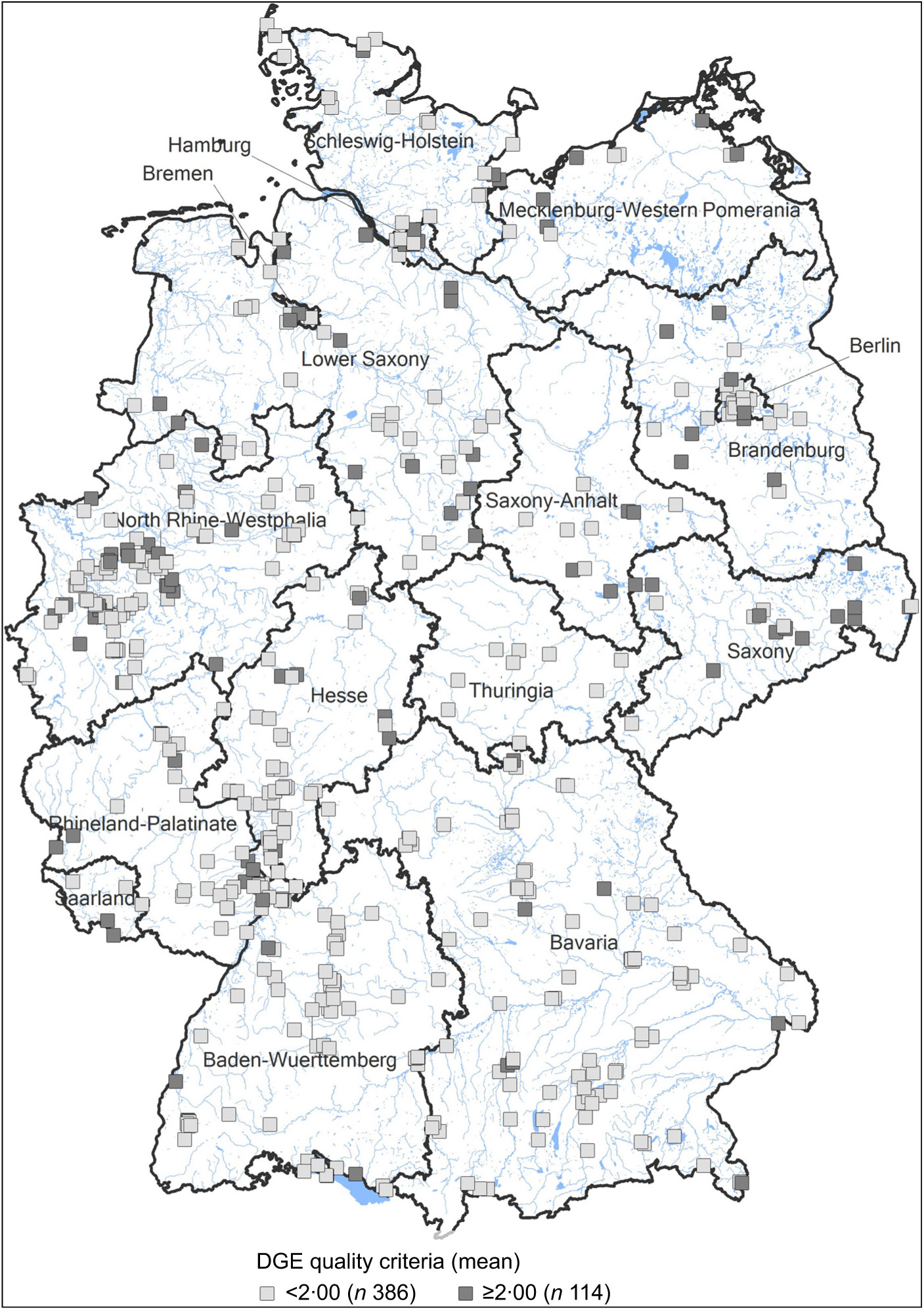

In addition to this, a cartographic illustration highlights regional differences (Fig. 3). The areas with the highest percentage of restaurants with a children’s menu that satisfied two or more of the above-mentioned criteria were found in the northern federal states, close to the North Sea and the Baltic Sea (e.g. Hamburg: 50 %, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania: 50 %, Bremen: 40 %). The lowest percentage rates were found in the southern states, furthest away from the coast (Baden-Wuerttemberg: 10 %, Bavaria: 8 %, Thuringia: 0 %; χ 2 = 60·37, df = 15, P < 0·001).

Fig. 3 Map of regions showing where restaurants with a children’s menu satisfied a mean of fewer than two or two or more of the quality criteria as found in the ‘Kids’ meals in Germany’ (KinG) study, a nationwide sample of menus from German full-service restaurants in 2017 (1877 meals from 500 menus). Quality criteria according to the recommendations made by the German Nutrition Society (DGE) regarding food preparation and service for childcare facilities and schools

No correlations were found between CMA score values and socio-spatial indicators. The Pearson correlation coefficients were +0·03 (population density, P = 0·54), +0·03 (average age, P = 0·60), −0·07 (proportion of foreigners, P = 0·17), +0·03 (unemployment rate, P = 0·53), +0·06 (child poverty rate, P = 0·22), −0·04 (household income, P = 0·36) and +0·04 (number of overnight stays by tourists, P = 0·43). A post hoc power analysis found that a sample size of 8719 or 1599 restaurants would have been needed in order to achieve a level of 5 % significance for these weak correlation coefficients (r 2 = +0·03/r 2 = −0·07).

The first of the separate validation samples showed that 81 % of all restaurants posted their menu online. The second separate validation sample comprised only restaurants without an online menu. The range of children’s menus available in these restaurants was not found to be significantly different from our original study sample in terms of the types of dishes offered, price or number of DGE criteria satisfied. Likewise, significant differences were not found in the percentage distribution of the meals across the six previously described categories. Considerable overlaps were found in the confidence intervals for all outcomes (P > 0·05).

Discussion

Principal findings and contribution to the current state of research

First, it was found that children’s menus are neither designed to be child-friendly nor sufficiently informative. This refers to both the opportunity to depict dishes in an appropriate manner (e.g. in a picture) as well as giving parents relevant information (e.g. about nutritional values, types of meat, etc.) which would be necessary to judge the nutritional quality of the meal. Second, the range of foods available is essentially limited to just a few types of dish. French fries dominate the menu, whether as a side dish or even as the main component of a meal. Measures that are easy to implement, such as the use of wholegrain products, milk and/or healthy types of oil (e.g. olive oil or rapeseed oil) in cooking, or including fruit, mineral water or milk as part of the meal, are very rarely seen. On average, of the eleven criteria derived from the DGE recommendations concerning ingredients and preparation methods for children’s meals, only 1·33 (sd 1·03; arithmetic mean and sd; minimum–maximum: 0–7) criteria were satisfied.

The menus of full-service restaurants that were included in the study are dominated by low-cost dishes that are quick and easy to prepare and which are similar to the dishes found in fast-food chains. From the restaurant owner’s point of view, these frozen and deep-fried (convenience) products have the advantage that they have a long storage life and that hygiene standards can be easily observed due to the high cooking temperatures involved(29).

The six most common types of meals found on the menus were dominated by highly processed foods. Highly processed foods typically have a higher energy density and contain higher amounts of saturated fats, trans-fats, free sugars and sodium than freshly prepared meals(Reference Monteiro, Moubarac and Cannon30 , Reference Louzada, Ricardo and Steele31). In contrast, such foods are low in dietary fibre, vitamins and micronutrients(Reference Monteiro, Moubarac and Cannon30 , Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Levy32). Moreover, experimental studies have clearly demonstrated that such foods have a high glycaemic load and a low satiety potential(Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Levy32 , Reference Fardet33). Other studies have shown that a higher consumption of highly processed foods is associated with lower nutritional quality (e.g. lower consumption of fruits, vegetables, dietary fibre, vitamins and minerals) among children and adolescents(Reference Cornwell, Villamor and Mora-Plazas20 , Reference Louzada, Ricardo and Steele31 , Reference Vandevijvere, De Ridder and Fiolet34). In addition to this, studies from various countries have shown that diets composed of such highly processed foods are associated with an increased risk of children and adolescents becoming overweight or obese(Reference Louzada, Baraldi and Steele35–Reference Diethelm, Gunther and Schulze37). It has also been found that highly processed foods have a negative effect on the lipid profiles of pre-school children and could therefore be a risk factor for developing CVD(Reference Rauber, Campagnolo and Hoffman38).

The quality criteria set by the DGE refer to both the menu design and the nutritional quality of the meals themselves. The same distinction was also found in a systematic review of community-based interventions for improving food environments in the food-service industry. The interventions compiled in that review also aimed at improving information provided at the point of purchase on the one hand and improving the actual foods being offered on the other. The authors concluded by saying that the most successful approach was one which combined measures to improve information at the point of purchase (e.g. by using labels such as ‘healthy dining’, ‘low in saturated fat’ or ‘good for health’, or in the form of providing health-related information and motivating games printed on tray covers) with extending the range of foods on offer to include more healthy alternatives(Reference Valdivia Espino, Guerrero and Rhoads8). The systematic review also showed that of the twenty-seven studies included in the review, twenty-six were from North America (twenty-one from the USA, five from Canada). The remaining study was a small, regional study conducted in a Dutch restaurant with fewer than 100 participants(Reference Papies and Veling39). It should also be mentioned that none of the published studies included in the above-mentioned review were explicitly designed to look at meals aimed at children and adolescents. In consideration of the current state of research, it is evident that the KinG study presented here fills a gap in the literature, specifically focusing on the food environment for children in a major country outside North America.

Limitations and strengths

First, our data do not allow for any conclusions to be drawn about the aspect of consumer demand, i.e. actual ordering and consumption behaviour. Despite in-depth research, we could not find any data about turnover, order figures or consumption behaviour within the children’s meals sector. This topic also receives very little attention in relevant industry reports, such that this point must continue to be considered a gap in the research, at a national and international level. Second, our data do not allow for the derivation of any information about portion size or quantitative data on specific ingredients or nutrients. Third, self-service and chain restaurants were excluded from the sample group. The study therefore does not allow for any statements to be made about the situation in chain restaurants. However, unlike full-service restaurants, several relevant studies (including those cited herein) have already been conducted looking at fast-food restaurants.

The strengths of the present study include the nationwide approach to sampling and the strictly differentiated and meticulous data capture procedure. The German food-service industry is organized at a federal level and characterized by its medium-sized, owner-operated structure and the large number of independent businesses. The standardized quota sampling procedure takes this into account as it is based on official tax data records. Concerning the structure and distribution of food-service establishments across the sixteen German federal states, our data set can be considered representative. The validation studies that were carried out in addition to the main sample did not find any indication of selection bias. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to evaluate the quality of children’s meals served in restaurants outside the USA. This may be due to the effort that is involved with such a study; it requires considerably less effort to investigate so-called ‘kids’ meals’ within fast-food and chain restaurants (McDonald’s, Wendy’s, KFC, Burger King, Arby’s, Taco Bell, etc.) as all the relevant information and meal combinations are available publicly, e.g. can be found online(Reference O’Donnell, Hoerr and Mendoza40). In contrast, for the present study, it was necessary to identify and evaluate every single meal in every single restaurant, making the process considerably more laborious. However, in so doing, it has shed light on the quality of children’s food in typical German full-service restaurants for the very first time.

Conclusions

The restaurant setting is considered an important food environment and offers an ideal opportunity to expose children to healthy foods, potentially affecting dietary intake during the restaurant meal as well as increasing children’s and adolescents’ receptivity to healthy but hitherto potentially unknown types of food or cooking style(Reference Shonkoff, Anzman-Frasca and Lynskey41). Our findings show that this opportunity is being missed in many German restaurants. In view of the great diversity of available food options and the historically different cooking cultures, it should be possible to improve the food environment specific to children and adolescents in Germany. Moreover, it would not only benefit the primary target group of children and adolescents, but ultimately also the restaurant owners themselves, for example by creating a better public image and a distinct, unique selling point.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements:The authors would like to thank Philipp Kadel, BSc Psychology (Mannheim University, Germany), for his support of this research and for creating the graphics. This paper would not have been possible without the support of Laura Schilling, MSc (Mannheim Institute of Public Health, Social and Preventive Medicine), in creating the cartographic figures. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: S.S. and J.H.-K. were responsible for study design, L.R. for data acquisition. S.S., J.H.-K. and L.R. analysed and interpreted the data set and drafted the manuscript. S.S. coordinated the publication process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The ethics committee responsible confirmed that, in accordance with current German laws, an ethics vote was not required for the study design, as the study does not work on or with people or their data (written statement to the first author from Prof. Dr Striebel, Chairman of Ethics Committee II of the Mannheim Medical Faculty, Heidelberg University, Germany, dated 20 June 2018).