Obesity and overweight are major public health issues among the general population in both developed and developing countries(Reference Vereecken, Tood and Roberts1–Reference Liou, Liou and Chang4). Obesity in children is of particular concern because it is associated not only with several physical and psychological consequences during childhood(Reference Kelishadi5–Reference Hamidi, Fakhrzadeh and Moayyeri7) but also with long-term morbidity and premature mortality as well as physical disability in later life(Reference Reilly and Kelly8). Moreover, childhood overweight/obesity is a determinant of obesity in the adolescent period linked with a number of conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, IHD and stroke(Reference Guijarro De Armas and Monereo Megias9, Reference Wabitsch, Hauner and Hertrampf10). The risk of adult overweight is about twofold greater for individuals who were overweight as children compared with individuals who were not overweight. Even moderate overweight in adolescence is associated with excess mortality in adulthood(Reference Must11).

The prevalence of childhood obesity has been increasing in Western countries in recent decades(Reference Must11–Reference Steinbeck15). Similarly, in other geographic regions such as the Middle East countries including Iran, the prevalence of obesity in children is also rising. Recent reports indicate that over 15 % of children living in Iran and neighbouring countries are overweight or obese(Reference Kelishadi5, Reference Mirmiran, Sherafat-Kazemzadeh and Jalali-Farahani16–Reference Maddah and Nikooyeh19). The high prevalence rate of overweight/obesity among children in northern Iran is of particular concern and worries families into seeking weight-reduction programmes(Reference Maddah and Nikooyeh19). Several factors such as change in lifestyles and diet, urbanization, lack of adequate physical activity and devoting greater time to sedentary activities like television viewing and playing on a computer should be considered as major causes of overweight/obesity in various countries(Reference Reilly and Kelly8, Reference Must11, Reference Lowry, Wechsler and Galuska20–Reference Al-Kloub, Al-Hassan and Froelicher23). Although a number of factors associated with obesity in children and adolescents seem to be similar in various countries, nevertheless the distribution of these factors and their contribution to the development of childhood obesity may be different across different populations(Reference Reilly and Kelly8, Reference Discigil, Tekin and Soylemez17, Reference The, Suchindram and Popkin18, Reference Lowry, Wechsler and Galuska20, Reference Maddah24).

With regard to the subsequent socio-economic public health burden of childhood obesity(Reference Sanderson, Patton and McKercher6, Reference Hamidi, Fakhrzadeh and Moayyeri7), these observations emphasize the need for preventive measures to control overweight and obesity at earlier stages of life. The greatest health burden of overweight in children and adolescents arises from its long-term consequences. Therefore, identification of factors responsible for overweight/obesity can be helpful for both prevention and treatment. Among the many associated factors of obesity, less attention has been paid to the relationship between physical activity and obesity in Iranian children and data in this context are lacking(Reference Maddah and Nikooyeh19, Reference Maddah24–Reference Kelishadi, Pour and Sarraf-Zadegan28).

For these reasons, the present study aimed to: (i) determine the prevalences of overweight and obesity among schoolchildren living in northern Iran; (ii) specify their levels of physical activity; and (iii) explore the relationship between overweight/obesity and physical activity.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted on a sample of 1200 adolescents who were studying in elementary and high schools in Babol, northern Iran, in 2008. Healthy students with no known systemic or debilitating conditions such as chronic asthma, bronchiectasis, major thalassaemia, chronic inflammatory arthritis or myopathy at age 12–17 years were included in the study. We used cluster sampling techniques in the sampling procedure. In the first step, we defined school as the cluster; since schools in our culture are exclusive for boys only and girls only, we selected twenty high schools (ten for males and ten for females) and twenty elementary schools (ten for males and ten for females) by proportional probability of the number of students in each school using a systematic sampling technique based on the cumulative frequency of the total number of students in schools for each gender. In the second step, for each grade and each gender, ten students were selected using systematic sampling; thus for three grades, thirty students were selected within every school. Overall, for forty schools (twenty high schools and twenty elementary schools), 40 × 30 = 1200 students were recruited in the study. This sample size allows estimation of the rates of obesity and overweight in which, with presumption of prevalence of 15 %, the maximum marginal error would be about 0·03 with a 95 % level of confidence.

All selected adolescents were interviewed; the interviews were carried out in school, with no adolescent refusing, by nursing students and school health-care givers who received similar instruction. Demographic data, including age, gender, type of school (private/public), birth order, family size, father's and mother's education level and occupation, as well as the number of hours spent watching television and playing computer games daily were collected by a specially designed questionnaire. Data on leisure-time and sport physical activities were collected by a standard Baecke questionnaire on 5-point scales; leisure-time and sport physical activity indices were calculated using the Baecke formula(Reference Baecke, Burema and Frijters29). The reliability of leisure-time and sport physical activity data was assessed in a pilot study using the Cronbach α coefficient, which was >0·85. After the interview, height and weight were measured by standard methods. Body weight was assessed using a Seca digital scale while the student stood in light clothing with no shoes. Standing height was measured without shoes using a portable stadiometer. The reliability of measurements of height and weight were assessed by repeated measurements on the same students using the intra-class correlation coefficient, which was >0·95. BMI (kg/m2) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided to square of height in metres.

The diagnosis of obesity, overweight and underweight was determined by comparing BMI values with the BMI index for age and sex percentiles set by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2000(30), in which BMI ≥95th percentile was regarded as obese, 85th ≤ BMI < 95th percentile as overweight and BMI < 5th percentile as underweight; those with 5th ≤ BMI < 85th percentile were categorized as normal weight. In addition, we used tertile cut-offs for categorization of the leisure-time physical activity index and sport physical activity index as low, moderate and high for values of 0–1·40, 1·41–3·70 and 3·71–5·00, respectively. The study proposal was approved by the Research and Ethical Committee of Babol University of Medical Sciences and informed consent was obtained prior to the adolescents’ participation in the study.

Statistical analysis

In bivariate analysis, we used the t test (or the Wilcoxon test for data with skewed distribution) for comparison of the means of continuous variables and the χ 2 test for categorical variables. We also applied logistic regression analysis to estimate the unadjusted and age- and sex-adjusted odds ratios of overweight and obesity for different levels of demographic and lifestyle factors. Age- and sex-adjusted odds ratios for the different levels of leisure-time and sport physical activities were calculated and also additional adjustment was carried out for all covariates such as age, gender, birth order, family size, type of school, father's and mother's educational level, and number of hours spent watching television and playing computer games daily. We also estimated the 95 % confidence intervals of the odds ratios. P values < 0·05 were considered to indicate statistical significance and all significance levels were two-sided. To investigate the effect of age on overweight/obesity we performed an additional analysis according to age groups of <15 and ≥15 years. We also categorized the number of hours watching television as ≥3 h/d v. <3 h/d, and for playing computer games as ≥2 h/d v. <2 h/d, in the logistic regression analyses. We used the SPSS statistical software package version 16·0 in our analysis.

Results

A total of 1200 adolescents (50 % males) with mean age of 14·2 (sd 1·7) years were entered into the study. Some 82·5 % of the adolescents were selected from public schools and the remainder came from private schools. Approximately 73 % of the adolescents were the first or second in birth order; family size consisted of four persons or fewer for 51 % of the adolescents. The father's education level was either elementary/high school or college in over half of the study population; university-level education was observed in 15·4 % of the fathers. The corresponding values for elementary/high school and university education levels in mothers were 27·8 % and 6·1 %, respectively.

Overall, the prevalence rates of overweight and obesity among the whole population were 15·1 % and 8·3 %, respectively. The proportion of obesity was significantly higher in boys than in girls (10·2 % v. 6·5 %, OR = 1·65, 95 % CI 1·06, 2·45, P = 0·028) whereas the proportions of overweight between the two groups did not differ (15·3 % v. 14·9 %; Table 1). Similarly, there was no significant difference in BMI values between the two sexes (Table 3). The prevalence rates of obesity in boys and girls aged <15 years were 8·7 % and 7·2 %, respectively (P = 0·47), whereas in the age group of ≥15 years they were 11·7 % and 5·5 %, respectively (P = 0·01; Table 1).

Table 1 The distribution of BMI status by age and sex: adolescents aged 12–17 years (n 1200), Babol, northern Iran, 2008

P < 0·05 considered as statistically significant.

*Determined with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention clinical growth charts (2000)(30).

†For the difference in BMI status at age 12–14 years v. 15–17 years.

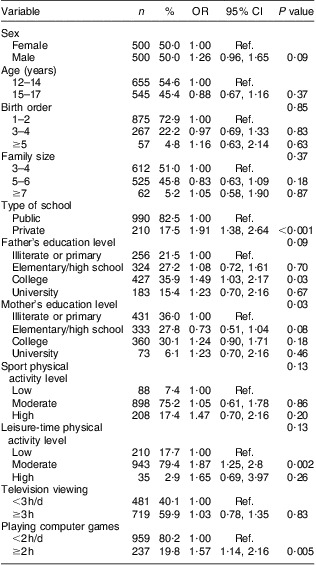

In the entire population, the proportion of boys and girls with high, moderate and low levels of leisure-time physical activity was 2·9 %, 79·4 % and 17·7 %, respectively. The corresponding values for high, moderate and low levels of sport physical activity were 17·4 %, 75·2 % and 7·4 %. The levels of leisure-time and sport physical activities were significantly higher in boys than in girls (P < 0·001; Table 2). The mean durations of television viewing were not significantly different between the two sexes (Table 3). The odds of overweight/obesity tended to be higher in boys compared with girls (OR = 1·26, 95 % CI 0·96, 1·65). Surprisingly, the moderate level of leisure-time physical activity was significantly associated with increased risk of overweight/obesity when compared with the low level (OR = 1·87, 95 % CI 1·25, 2·80, P = 0·002), whereas the high level of leisure-time physical activity did not significantly increase the risk of overweight/obesity (OR = 1·65, 95 % CI 0·69, 3·97, P = 0·26). Studying in private school was also associated with increased risk of overweight/obesity compared with public school (OR = 1·91, 95 % CI 1·38, 2·64, P < 0·001). Playing computer games was significantly associated with overweight/obesity (the odds for ≥2 h/d v. <2 h/d increased by 57 %; OR = 1·57, 95 % CI 1·14, 2·16, P = 0·005). Higher levels of education in mothers or fathers were associated with greater risk of overweight/obesity: educational levels greater than high school (>12 years of education) were associated with non-significant increased risk of overweight/obesity (Table 4). After adjusting age, sex and other demographic covariates by logistic regression analysis, the associations between physical activity and overweight/obesity remained significant only for moderate leisure-time physical activity, whereas the association between the sport physical activity index and overweight/obesity did not reach statistical significance (Table 5).

Table 2 The distribution of physical activity levels by sex: adolescents aged 12–17 years (n 1200), Babol, northern Iran, 2008

P < 0·05 considered as statistically significant.

*Determined with the Baecke questionnaire(Reference Baecke, Burema and Frijters29).

†For the difference in physical activity level of boys v. girls.

Table 3 Characteristics of the study population according to sex: adolescents aged 12–17 years (n 1200), Babol, northern Iran, 2008

P < 0·05 considered statistically significant.

*For the difference in characteristics of boys v. girls.

†Median is reported instead of the mean because of skewed distribution; P value is derived from the Wilcoxon test.

Table 4 The distribution of demographic characteristics and physical activity, and corresponding odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals for overweight/obesity: adolescents aged 12–17 years (n 1200), Babol, northern Iran, 2008

Ref., referent category.

P < 0·05 considered statistically significant.

Table 5 Adjusted odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals for overweight/obesity according to level of physical activity: adolescents aged 12–17 years (n 1200), Babol, northern Iran, 2008

Ref., referent category.

P < 0·05 was considered as statistical significant.

*Additional adjustment was carried out by type of school, television viewing, playing computer games, father's education level, mother's education level, birth order and family size.

Discussion

The present study found a high prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents living in northern Iran. Many factors such as moderate leisure-time physical activity, sedentary activities such as playing computer games for >2 h/d, higher levels of parental education and studying in private schools were significantly associated with overweight/obesity. In adolescent boys, the prevalence of obesity was higher than in the girls, despite boys being more active than girls. The relationship between moderate leisure-time physical activity and overweight/obesity remained significant after adjusting for age, sex as well as other associated factors such as television viewing, playing computer games and parental education levels using multivariate analysis.

Our study revealed the prevalence of obesity to be similar in the two genders before the age of 15 years, but to increase significantly thereafter in the adolescent boys as compared with the adolescent girls. This finding indicates that the progression from overweight to obesity with increasing age differs between boys and girls. This discrepancy may be attributed to reawakening of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis during puberty which results in different body composition, including regional distribution of fat and bone mineralization, between the two sexes. The adolescent boys gain much more lean body muscle and bone, whereas the adolescent girls gain a greater amount of fat than the boys(Reference Rogol31). In addition, the lower rate of obesity in adolescent girls in our study can be attributed to their lower food intake for keeping or preserving a suitable body image because their tendency to obesity decreases as they grow up, whereas such tendency is usually ignored in adolescent boys(Reference Mirmiran, Sherafat-Kazemzadeh and Jalali-Farahani16).

The prevalence of overweight/obesity in children and adolescents has been investigated in several previous studies(Reference Maddah and Nikooyeh19, Reference Lowry, Wechsler and Galuska20, Reference Mohammadpour-Ahranjani, Rashidi and Karandish26, Reference Shatoor, Mahfouz and Khan32–Reference Isasi, Whiffen and Campbell36). While in a number of studies the prevalence rates of overweight and obesity were higher than or comparable to those in our study(Reference Maddah and Nikooyeh19, Reference Mohammadpour-Ahranjani, Rashidi and Karandish26, Reference Goyal, Shah and Saboo35, Reference Isasi, Whiffen and Campbell36), in a few other studies the rates were lower than ours(Reference Hands, Chivers and Parker27, Reference Baecke, Burema and Frijters29, Reference Rogol31). However, the prevalence rates with regard to overweight or obesity differed between boys and girls in the various studies across different study populations from other geographic areas of Iran(Reference Mohammadpour-Ahranjani, Rashidi and Karandish26, Reference Rogol31), neighbouring countries(Reference Shatoor, Mahfouz and Khan32–Reference Goyal, Shah and Saboo35) and the USA as well(Reference Lowry, Wechsler and Galuska20, Reference Isasi, Whiffen and Campbell36). In a study by Mohammadpour et al. among adolescents aged 11–16 years in Tehran, the capital city of Iran, the overall prevalence of overweight was higher than our results (21·1 % v. 15·1 %) but the prevalence of obesity was comparable (7·8 % v. 8·3 %) and the prevalence of overweight among the girls was significantly higher than among the boys (23·1 % v. 18·8 %)(Reference Mohammadpour-Ahranjani, Rashidi and Karandish26). In another study of 12–17-year-old schoolgirls in Rasht, northern Iran, a population with similar characteristics to the present study, the overall prevalence of overweight was higher but the prevalence of obesity was lower compared with our findings. Maternal education was positively related to overweight/obesity of the girls(Reference Maddah and Nikooyeh19).

In other populations with relatively similar lifestyles from neighbouring countries, the prevalence of overweight/obesity was also different between boys and girls. In a study of secondary-school adolescent boys from Saudi Arabia, the prevalence of obesity was much higher than our results(Reference Shatoor, Mahfouz and Khan32); whereas findings from studies in Turkish adolescents revealed lower prevalence rates of overweight and obesity compared with our results(Reference Oner, Vatansever and Sari33, Reference Simsek, Akpinar and Bahacebasi34). In a study of Indian schoolchildren aged 12–18 years, the prevalence of overweight in boys was comparable to our findings but the prevalence in girls was lower. However, the prevalence of obesity in both boys and girls was much lower than our findings(Reference Goyal, Shah and Saboo35).

In two studies among US adolescents, the prevalences of overweight were different. In a study of public-school children aged 11–18 years with different lifestyles and diets compared with our study, the prevalence of overweight and obesity was 21·7 % and 22·5 %, respectively, which was much higher than our study. Similar to our findings, the prevalence of obesity and severe obesity was higher among the adolescent boys than the adolescent girls. However, the prevalence of overweight was higher among the adolescent girls than the boys(Reference Isasi, Whiffen and Campbell36). In another study of US high-school students with different ethnicity, race and gender, the prevalence of overweight was lower than in the present study(Reference Lowry, Wechsler and Galuska20).

Obesity has a complex aetiology and several variables including genetic background, nutrition, physical activity and lifestyle habits may be considered responsible factors(Reference Steinbeck15). In addition, parental, socio-economic status (SES) and environmental factors are also important. Nutrition and the level, intensity as well as duration of physical activity, which are important factors in obesity, may vary in different populations across various geographic areas. Therefore, depending upon the study population, the associated factors of obesity may differ even within the same country(Reference Reilly and Kelly8, Reference Must11, Reference Lowry, Wechsler and Galuska20–Reference Al-Kloub, Al-Hassan and Froelicher23).

Considering the high prevalence rates of obesity and overweight among the adult population of northern Iran(Reference Hajian-Tilaki and Heidari37), obesity in children adds a further burden to adult health problems and warrants preventive measures. Although the contributory role of physical activity in the prevention of primary or secondary obesity is less clear(Reference Steinbeck38), it is the major component of energy expenditure. The relationship between physical activity and fatness was shown in a cross-sectional study of 780 children by Ruiz et al.(Reference Ruiz, Rizzo and Hurtig-Wennlöf39). In that study, lower body fat was significantly associated with higher levels of vigorous physical activity, but not with moderate or total physical activity. The intensity of physical activity, especially vigorous physical activity, but not total physical activity, was negatively related to body fatness. Participation in moderate physical activity and total physical activity did not explain a significant proportion of the variance in body fat. These findings suggest that intensity rather than amount of physical activity may be more important in relation to the prevention of obesity in children(Reference Ruiz, Rizzo and Hurtig-Wennlöf39). In the present study, the positive relationship between moderate physical activity and overweight/obesity may be explained by excess energy intake and/or reduced energy expenditure from insufficient intensity of physical activity. Insufficient vigorous physical activity was shown as a risk factor for higher BMI for adolescent boys and girls(Reference Patrick, Norman and Calfas40). Although we did not provide data with respect to food intake, frequent intake of snacks during physical activity is often encouraged to physically active children by parents, particularly in educated or high-income families, in our culture. High intake of energy from snacks can counteract the effect of physical activity. This issue can be considered important in explaining the various prevalence rates of overweight/obesity observed in studies from various geographic areas or the different prevalence rates between boys and girls regardless of other associated factors. High intake of snacks, and insufficient consumption of fruits and vegetables, have been considered as associated factors of obesity in adolescents(Reference Mirmiran, Sherafat-Kazemzadeh and Jalali-Farahani16, Reference Ranjit, Evans and Byrd-Williams41). A correlation between obesity and intake of sweet foods while watching television or playing on a computer has been shown in a few but not all studies(Reference Reilly and Kelly8, Reference Lowry, Wechsler and Galuska20, Reference Slater, Ewing and Powell42, Reference Zalilah, Khor and Mirnalini43).

Food consumption and the pattern of diet selection are income-dependent. Thus children from higher SES groups are expected to study in private schools and to have greater potential to select high-quality foods; they may also devote greater time to low-level physical activities like television viewing or computer use and consume greater amounts of high-energy foods. On the contrary, in children from lower SES families, the potential for selection of such foods and sedentary activities is lower and so the possibility of obesity is lower(Reference Slater, Ewing and Powell42). This can also explain the association between overweight/obesity and studying in private school as well as among families with higher levels of education.

However, the influences of SES on BMI vary across different populations and high obesity prevalence has also been reported in low SES populations(Reference Mirmiran, Sherafat-Kazemzadeh and Jalali-Farahani16). Parental obesity may also affect children's BMI through genetic contribution or exhibition of behaviour patterns(Reference Steffen, Dai and Fulton22).

The results of the present study should be considered within its limitations. Although the level and duration of physical activity were evaluated uniformly across the different comparison groups, the possibility of over- or underestimation of self-reported data cannot be ignored. We did not provide data with regard to regular food intake and snacking to evaluate energy intakes. Higher intake of energy can repress the beneficial effects of physical activity on weight. Energy expenditure in overweight adolescents is lower compared with normal-weight or underweight adolescents(Reference Zalilah, Khor and Mirnalini43). The positive association between overweight/obesity and physical activity may be interpreted differently with regard to the direction of association. Because of the cross-sectional nature of our study, the true direction of causality is unclear. It is equally possible that being obese resulted in further activities or obese children were encouraged to engage in greater levels of physical activities by their educated parents. However, the real direction of the effect of physical activity on weight can be shown only in a prospective study.

Conclusions

The findings of the present study indicated a high prevalence rate of overweight/obesity in adolescents, particularly boys, living in northern Iran. Several factors such as moderate leisure-time physical activity, sedentary activities with a computer, higher levels of parental education and studying in private schools were related to obesity or overweight. Among these factors, the independent positive relationship of leisure-time physical activity with overweight/obesity should be attributed to insufficient intensity of physical activity or suppression of physical activity's beneficial effects by a higher intake of food. However, further prospective studies with concurrent calculation of food intake are required to determine the relationship between physical activity and overweight/obesity.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Deputy of Research of Babol University of Medical Sciences. There is no conflict of interest to disclose. K.H.-T. developed the study protocol, managed the data collection and analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. B.H. contributed to the study design, wrote the introduction and discussion sections of the manuscript, and revised the whole manuscript. The authors would like to thank the nursing students of Babol University of Medical Sciences and the school health-care givers for their assistance in data collection.