In many industrialized countries, school nutrition policies have been established in order to promote healthier dietary habits and thereby to help prevent the development of overweight and obesity in the paediatric population( Reference Jaime and Lock 1 , Reference Fox, Dodd and Wilson 2 ). This is particularly relevant in France where children attend school from 08.00–09.00 to 16.00–17.00 hours and where most schoolchildren eat lunch provided by school canteens at least three times per week: 50 % in pre-schools and elementary schools and 64 % in secondary schools( Reference Dubuisson, Lioret and Dufour 3 ). Most French schools house a canteen and supply a hot meal composed of four to five courses (starter, main dish, side dish, dairy product and dessert). Children attending the canteen pay for the lunch. Apart from this hot meal, no other food offer is available at lunchtime at school. Schoolchildren are not allowed to bring packed lunches from home to eat in school canteens unless they require a special diet (due to diabetes type 1, food allergy, hereditary metabolic disorder, etc.).Footnote †

Since the early 2000s, the food environment at school has been part of the French national nutrition policies. The first initiative dated back from 1999, when guidelines on the composition of school meals were first published( 4 ) to help catering services design balanced meals. These guidelines were enclosed in 2001 in a circular† from the Ministry of Education dealing with food composition and food safety of school meals( 5 ). Taking into account the overall food environment at school, the morning snack was discouraged in pre-schools and elementary schools in 2004 by a circular from the Ministry of Education( 6 ) and beverages and food vending machines were banned by law( 7 ) in all schools in 2005. In 2007, the guidelines on school meal composition were revised( 8 ). These recommendations consist of food-group frequency guidelines, defining the minimum or maximum frequency with which fifteen food groups should be offered by school canteens over twenty consecutive meals. They also set adequate portion sizes according to three age classes: pre-schools (children aged 3–5 years old), elementary schools (children aged 6–10 years old) and secondary schools (adolescents aged 11–17 years old). The food-group frequency guidelines were established in order to achieve several nutritional goals: decrease total lipid and sugar intakes, obtain a more balanced fatty acids intake (less SFA and more n-3 PUFA) and increase fibre, Ca and Fe intakes. Acknowledging a previous study pointing out that school canteens did not implement all of the food-group frequency guidelines properly( Reference Dubuisson, Lioret and Calamassi-Tran 9 ), a law published in July 2010( 10 ) made the revised recommendations compulsory. The application decree and order were published in October 2011 and came into effect in September 2012( 11 , 12 ).

By improving the food and nutritional offer in school canteens, these national school meal regulations should contribute to healthier food choices at lunchtime( Reference Jaime and Lock 1 , Reference Vereecken, Bobelijn and Maes 13 – Reference Briefel, Crepinsek and Cabili 15 ). But, from a public health point of view, the regulations would be more efficient if they also impacted the whole diet of schoolchildren. It has already been suggested that overall dietary or nutrient intakes of children can be improved by school nutrition policies( Reference Briefel, Crepinsek and Cabili 15 – Reference Briefel, Wilson and Gleason 19 ). Eating well-balanced lunches at school may also contribute to the nutritional education of children and improve their overall diet.

Given this background, the first objective of the present study was to investigate whether lunchtime dietary intake at school canteens was different from other locations. The second objective was to study the associations between school lunch attendance and the overall dietary intake of schoolchildren.

Materials and methods

All analyses conducted in the present study used the data from the second French national cross-sectional food consumption survey, INCA2. The INCA2 survey was carried out between December 2005 and May 2007 by the French Food Safety Agency (Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Aliments, AFSSA). At the time of the field survey, the first guidelines on school meal composition (1999) had been published but their implementation was not yet mandatory.

Study design and participants

Two nationally representative samples of individuals living in mainland France (3- to 17-year-old children and 18- to 79-year-old adults) were obtained by using a multistage cluster sampling design described in detail elsewhere( Reference Lioret, Dubuisson and Dufour 20 – Reference Dubuisson, Lioret and Touvier 22 ). A participation rate of 69 % was obtained for children aged 3–17 years, yielding a sample of 1455 children. Among them, twenty-six unschooled children were excluded. To compare the food intake of children in a school period context, the 280 children who were on holiday during the week of the survey were not retained. Eleven children with extremely low reported energy intake (EI), whose log(EI) was lower than [mean(EI) –3 sd], by age group, were considered as outliers( Reference Lioret, Touvier and Dubuisson 23 ) and excluded as well. Seventy remaining children with missing values on meal location or with incomplete food records (less than 7 d) were also excluded from the analyses. Finally, analyses were carried out on 1068 children (73·4 % of the initial sample), who were classified according to their school type. The school types were grouped according to their catering organization (pre-schools and elementary schools (PES) on the one hand and lower and upper secondary schools (SS) on the other hand).

These 1068 schoolchildren had 30 205 eating occasions (meals and between-meal snacks) during the survey week, among which 7261 were lunches. For the comparison of food group consumption according to location (school canteen v. other locations), only lunches eaten from Monday to Friday were retained (n 5219) in order to compare school-day lunches, and thirty-nine lunches with incomplete eating location were also excluded. Eventually, comparison of lunch composition according to location was performed on 5180 lunches, 2262 for PES children and 2918 for SS children.

Measurements

Dietary intake was assessed using a 7 d open-ended food record. Information on the demographic and socio-economic status and type of school attended by the children was collected using self-administered and face-to-face questionnaires.

A trained and certified investigator delivered the 7 d record and the self-administered questionnaire to the home and explained to the parents and their children how to complete them. Guidance with written instructions on the completion of the diary was also left with participants. Children aged 10 years or less were helped by their parents or caregivers to fill out the documents. After the week of the survey, the investigator came back and checked the accuracy of the information reported in the documents and amended it with the help of the participant if necessary. Then, the investigator administered the face-to-face questionnaire partly to the child and partly to his/her adult caregiver (mainly the mother; 80 %).

Each day of the food record was divided into three main meals (breakfast, lunch and dinner) and three between-meal eating occasions. For the main meals, participants indicated the eating location from six proposals (at home, at a canteen, at a friend’s home, at a fast-food outlet, at a restaurant or other). The participants were then asked to report as precisely as possible all food and beverage intakes. For meals eaten at the school canteen, the parents were encouraged to ask for the school menus in order to help the child correctly report his/her school meals. One line of the record corresponded to one item consumed (food or beverage) and thus to one eating occasion for this specific item. Foods and beverages recorded were then allocated a food code from the nomenclature including 1280 items( 24 ). This task was performed using an automated process followed by a manual one. The automated process based on logical rules allowed for the coding of 46 % of the reported foods/beverages. Then, two dietitians coded the remaining foods/beverages items manually. Finally, a third dietitian checked the code of all foods/beverages items to ensure consistency by food group and by food/beverage name. In the framework of our study, these 1280 food items were classified into thirty-four groups.

The face-to-face questionnaire included questions on socio-economic issues (household income, the occupation, employment status and educational level of the head of the household and the child’s caregiver), household living standards indices and the child’s school type. Other information, such as region, type of settlement in which the household was located and household composition, were collected during the face-to-face interview.

This survey was approved by the French Data Protection Authority (Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertés, CNIL). Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants and formally recorded.

Data analysis

All analyses were computed using the STATA statistical software package release 11. National representativeness of the initial sample of 1455 children was established by weighting individual data for unequal sampling probabilities and for differential non-responses by region, urban area size, age, gender, head of the household’s occupation, size of the household and season. The external data used came from the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE) national data set for 2005.

School lunch attendance was assessed as the number of lunches provided by the school canteen and eaten by the child during the survey week, grouped into three classes: never (no school lunch), occasional (1 or 2 school lunches) and regular (3 to 5 school lunches).

First, we compared the lunch food-group composition according to meal location. To this end, for each of the twenty-four food groups detailed in the Appendix, the proportion of lunches including at least one item of the food group was assessed according to eating location: school canteen and all other locations (at home, at a friend’s home, at a fast-food outlet, at a restaurant or other). Among the thirty-four food groups, ten food groups were excluded from analysis because they were almost never eaten by schoolchildren either at lunch or overall. The odds of consuming a food group at lunch according to its location were tested by mixed logistic regression in order to take into account the random effect of the child (xtlogit procedure). Analyses based on meals were adjusted for age (in years), gender and socio-economic and demographic characteristics previously identified as associated with school lunch participation( Reference Dubuisson, Lioret and Dufour 3 ). Second, we investigated the relationship between school lunch attendance and the individual food intake of children. The eating-occasion frequency of twenty-one food groups (excluding three food groups almost never eaten at lunch) was calculated as the sum of every line of the food record corresponding to the considered food group. Two eating-occasion frequencies were calculated: one considered all lunches in the week and the second considered all meals and snacks over the week in order to further investigate the relationship between school lunch and the other meals of the week. Both average individual eating-occasion frequencies were compared for the three levels of school lunch attendance, using tobit regression, which makes it possible to take into account both variations in non-consumer prevalence and in eating frequencies with school lunch attendance. Analyses based on individuals were adjusted for age (in years), gender and socio-economic and demographic characteristics. In addition, individual weighting factors and the complex sampling design effect were taken into account by using the survey procedures of STATA (svy: logistic, svy: tobit). With regard to multiple testing, a P value <0·005 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Description of the participants and lunches

The composition of the study sample of 1068 schoolchildren was examined with regard to the variables used (gender, age, region, urban area size, size of the household, head of the household’s occupation) in order to ensure the national representativeness compared with the overall sample of 1455 children. There was a slight over-representation of boys (53·9 % v. 45·1 % in the excluded sample, P=0·02). Included and excluded schoolchildren were also checked for confounding variables (educational level and employment status of the child caregiver, household wealth index, settlement type) and for usual school canteen attendance as estimated from the self-administered questionnaire( Reference Dubuisson, Lioret and Dufour 3 ). Our study sample showed an over-representation of children whose caregiver had a high educational level (executives, top management and professional categories: 38·2 % v. 22·5 % in the excluded sample, P<0·001). In addition, in the study sample of PES children, regular users of the school canteen (at least three times per week) were over-represented as compared with the excluded sample (53·6 % v. 37·8 %, P=0·01).

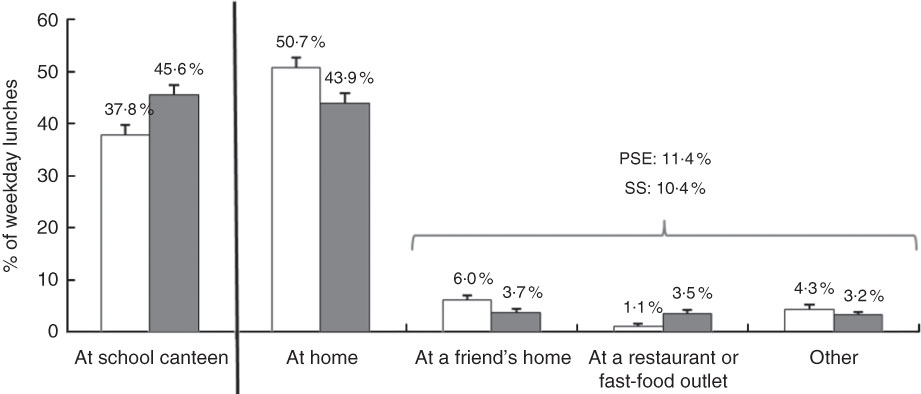

The characteristics of the 1068 schoolchildren are presented in Table 1, according to the two school types. About 64 % of the schoolchildren (61 % in PES and 67 % in SS) attended the school canteen at least once during the survey week. The location of the 5180 weekday lunches eaten by these children is described in Fig. 1. School canteens and the children’s home were the most common locations observed regardless of the age of the children. PES children had lunch more often at home and SS children had lunch more often at the school canteen (P<0·001).

Fig. 1 Distribution of the locations of weekday lunches of 1068 schoolchildren aged 3–17 years (![]() , pre-school and elementary school (PES) children, n

lunches 2262;

, pre-school and elementary school (PES) children, n

lunches 2262; ![]() , secondary school (SS) children, n

lunches 2918) selected from the second French national cross-sectional food consumption survey (INCA2, 2006–2007). Values are means with their 95 % confidence intervals represented by vertical bars

, secondary school (SS) children, n

lunches 2918) selected from the second French national cross-sectional food consumption survey (INCA2, 2006–2007). Values are means with their 95 % confidence intervals represented by vertical bars

Table 1 Characteristics of the 1068 schoolchildren aged 3–17 years selected from the second French national food consumption survey (INCA2, 2006–2007), according to school type

PES, pre-school and elementary school; SS, secondary school.

Dietary intake for weekday lunches according to meal location: school canteen v. other locations

For all school types, lunches provided by and eaten at school canteens included the following foods more frequently: bread, fish and seafood, mixed dishes, dairy products (cured cheeses for PES children and yoghurt and cottage cheeses for SS children), fresh fruit, fruit in syrup and stewed fruits, and sweet biscuits and pastries (Table 2). On the other hand, sandwiches and hamburgers, soft drinks, fruit juices, and chocolate and confectionery were found less frequently in school lunches. Other results were school-type specific. For PES children, lunches eaten at the school canteen also provided vegetables and soups more often and potatoes less often. For SS children, they included ice cream and dairy desserts, pizzas and savoury pastries, and drinking water more frequently.

Table 2 Prevalence of twenty-four food groups at lunch, and adjusted odds ratio (ORadj and 95 % confidence interval) for the presence of a given food group at lunch according to location (school canteen v. other locations), among the 1068 schoolchildren aged 3–17 years selected from the second French national food consumption survey (INCA2, 2006–2007)

PES, pre-school and elementary school; SS, secondary school; Ref., referent category.

* Adjusted for child’s age (in years) and gender, region, number of adults in the households, child caregiver’s educational level and working status.

† Adjusted for child’s age (in years) and gender, type of settlement in which the household was located, household wealth index and child caregiver’s educational level.

School lunch attendance and the weekly dietary intake of children

With regard to eating frequencies at lunchtime (Table 3), the more schoolchildren attended the school canteen, the more they ate fruit in syrup and stewed fruit, and sweet biscuits and pastries. In addition, in PES children, lunchtime eating frequencies of cheese, fish and seafood, vegetables and mixed dishes increased with school lunch attendance, whereas lunchtime eating frequencies of meat products decreased. In SS children, the relationship between school lunch attendance and lunchtime eating frequencies was positive for fresh fruit and negative for sandwiches and soft drinks.

Table 3 Average lunchtime eating frequency and average overall eating frequency of twenty-one food-groups (Fq/week and 95 % confidence intervals), and relationship with the level of school lunch attendanceFootnote *, among the 1068 schoolchildren aged 3–17 years selected from the second French national food consumption survey (INCA2, 2006–2007)

PES, pre-school and elementary school; SS, secondary school; SLA, school lunch attendance.

* SLA: never=0 lunches/week; occasional=1–2 lunches/week; regular=3–5 lunches/week.

† P value for at least one significant difference between the three levels of SLA (‡ denotes P value testing the linear association between the food-group intake and the three levels of SLA from never to regular). For PES children, the test is adjusted for child’s age (in years) and gender, region, number of adults in the households, child caregiver’s educational level and working status. For SS children, the test is adjusted for child’s age (in years) and gender, type of settlement in which the household was located, household wealth index and child caregiver’s educational level.

Considering overall eating frequencies (Table 3), schoolchildren with higher school canteen attendance ate fruit in syrup and stewed fruit more frequently. PES children also ate more fish and seafood, vegetables, mixed dishes, and sweet biscuits and pastries. SS children ate fewer sandwiches and hamburgers, and drank less soft drinks.

Discussion

The present study assesses the extent to which school lunch attendance is linked to differences in children’s diets in France. It also provides a point of reference for future evaluations of the efficiency of the new regulations on school meal composition for improving food intakes of children who eat school lunches.

Study strengths and weaknesses

All our analyses were based on a national sample of schoolchildren aged 3–17 years. The exclusion of 27 % of children from the initial sample may have an impact on the generalization of our results to France as a whole, but not on the relationship we observed between school lunch attendance and the dietary intakes of children. Strict inclusion criteria were applied for the children considered in the final sample in order to avoid misclassification by school lunch attendance frequency or school type. In addition, we compared the intakes of children within a school context (e.g. excluding children on holiday) in order to account for the fact that different time constraints can lead to different food habits( Reference Rockell, Parnell and Wilson 25 , Reference Cullen, Lara and de Moor 26 ).

Our study presents some weaknesses. First, we chose to study the overall diet of children using a food group approach since the new regulations are based on target food groups. However, we acknowledge that a dietary pattern approach would have allowed us to more effectively consider their overall diet. Second, we cannot rule out a potential differential memory bias in food reporting for school lunches since some children may not have taken the 7 d diary and the photographic food portion booklet to school. This bias may have been stronger for younger children( Reference Warren, Henry and Livingstone 27 ). Nevertheless, children were initially trained to fill in the food record by the interviewer during the first visit and parents were asked to have a copy of the school menu at home. In addition, the time interval between eating and recording was limited to a few hours. All of these elements would help the children to more accurately report their consumption( Reference Warren, Henry and Livingstone 27 – Reference Baxter, Thompson and Davis 31 ). Finally, since our findings are based on a cross-sectional study, we cannot draw any conclusions on the causal link between eating lunches provided by schools and the overall dietary intakes of children.

School lunch attendance and dietary intakes

We investigated the relationship between school lunches and dietary intakes at both meal and individual levels in order to more effectively describe the links between school lunch attendance and the overall dietary intakes of schoolchildren.

First, we showed that, in France, foods eaten at lunchtime at the school canteen differed from those eaten at other locations. Among the differences pointed out, some were in accordance with the national recommendations on school meal composition (more fruit, fish and seafood, dairy products and vegetables, and fewer sandwiches, soft drinks, chocolate and confectionery) whereas others highlighted needs for improvement (more sweet biscuits and pastries, ice cream and dairy desserts, pizzas and savoury pastries). Second, we confirmed that most of the differences in dietary intake found at the meal level remained at the individual level when accounting for the lunchtime diet. However, some differences in dietary intake found at the meal level were no longer observed at the individual level. This could be partly explained by a loss of statistical power due to a lower sample size at the individual level compared with the meal level, but also by compensatory dietary intakes during weekend lunches( 24 , Reference Rockell, Parnell and Wilson 25 ). Finally, we tested the relationship between school lunch attendance and overall food-group eating frequencies. Dietary habits differ from one meal to another and from one day to another according to time constraints (school days or not)( Reference Rockell, Parnell and Wilson 25 , Reference Cullen, Lara and de Moor 26 , 32 ) and conviviality( Reference Larson and Story 33 ). Therefore, consumption during other meals, in different locations or on non-school days, may attenuate the relationship of school lunch with the overall dietary intakes of schoolchildren. Combining the results of the individual lunchtime and overall eating frequencies provided further information on the relationships between school lunch attendance and overall food intake. When differences pointed out at lunchtime were weaker or reversed for overall food intake, these could suggest that the differences associated with school lunch attendance were counterbalanced during the other meals of the week. This situation was observed for instance for pasta, rice and wheat in SS children. It implies that a regulation aiming to improve school lunch composition needs fostering through educational support. However, when significant associations observed at lunchtime became stronger when overall food intake was accounted for, this could mean that children ate consistently more (or less) frequently the given food group across all meals. This therefore could be interpreted as school lunch attendance being associated with different food habits in children. Depending on their age, schoolchildren regularly attending school canteens more often consumed stewed fruit, fish and seafood, vegetables, mixed dishes in addition to sweet biscuits and pastries. Stewed fruit and fruit in syrup, as well as sweet biscuits and pastries, are indeed common desserts in school lunches( 34 ). They also consumed soft drinks and sandwiches less frequently than schoolchildren who never ate at the school canteen.

Several studies have already highlighted the influence of school canteens on children’s dietary habits, with regard to either the total diet, including weekend days( Reference Lopez-Frias, Nestares and Ianez 35 – Reference Raulio, Roos and Prattala 38 ), or only the school-day diet( Reference Clark and Fox 18 , Reference Briefel, Wilson and Gleason 19 , Reference Rogers, Ness and Hebditch 39 ). Our findings also suggest that diet as a whole is associated with school lunch attendance. Acknowledging the cross-sectional design of our study, the linear trend observed between school lunch attendance and dietary intake for most of food groups further supports the hypothesis of an influence of school lunch attendance on overall dietary intake. Therefore, even though it is not possible to conclude from our data that there is a causal impact of eating school lunch on the overall diet of schoolchildren based on cross-sectional results, our findings are in agreement with others which show that school lunch intakes can contribute significantly to overall diet( Reference Harrison, Jennings and Jones 37 ). However, the weaker relationship in SS children may be explained by the food choice available in SS canteens, which provides SS children the opportunity to choose the foods they like or are used to eating, and that are less likely to be healthy options( Reference Nelson, Lowes and Hwang 36 , Reference Condon, Crepinsek and Fox 40 ). SS children have more opportunities than younger children to select the foods they want to eat outside school, which enables them to more easily counterbalance their food intake at the school canteen. For these reasons, a more restrictive food choice at school lunch combined with educational support would be necessary to improve the overall diet of SS children.

Because of national specificities in school catering and lunch patterns, it is difficult to go further in the comparison of our findings with international studies dealing with school canteen participation and dietary intakes of children( Reference Briefel, Crepinsek and Cabili 15 , Reference Briefel, Wilson and Gleason 19 , Reference Lopez-Frias, Nestares and Ianez 35 – Reference Rees, Richards and Gregory 42 ). However, most of these studies support our findings, which show both beneficial (more vegetables, dairy products, fish and less soft drinks and sandwiches) and deleterious (more sweet and savoury snacks) aspects of school lunch on food intake. Focusing on the French situation, data from the former French INCA1 survey carried out in 1998–1999 showed similar differences in food intake with school lunch at both meal and individual levels( Reference Lafay, Volatier and Martin 43 ). Since some of the food intake differences observed at lunchtime seemed to contribute to the overall diet, we hypothesize that the new regulations could contribute to improving children’s diet at school in particular, and their whole diet on a more general level. Indeed, all the foods offered at schools will be affected by the regulations since vending machines on school premises have been banned( 7 ) and neither competitive foods nor packed lunches are allowed in French school canteens. However, it should be pointed out that school lunch participation remains low in children with underprivileged backgrounds (about 40 % v. 76 % in children with less underprivileged backgrounds)( Reference Dubuisson, Lioret and Dufour 3 ), whose dietary habits have been identified as being less in line with the national recommendations( Reference Lioret, Dubuisson and Dufour 20 , Reference Lioret, Touvier and Dubuisson 23 , 32 ). From a public health point of view, the effectiveness of the recent national regulations will therefore also depend on an increase in the school lunch participation of these children.

Conclusion

Lunchtime dietary intakes differ between the school canteen and other locations, with the differences being both potentially beneficial and deleterious. Some of these differences remain when considering the whole diet whereas others seem to be counterbalanced during the out-of-school meals, mostly in SS children. School meals are therefore likely to be a valuable opportunity to promote a healthy diet in children. The new national regulations on school meal composition contribute further to this trend provided that they are supported by educational measures, particularly in SS children. It would be beneficial to enable schoolchildren from underprivileged families to benefit more from these regulations, by finding a way to enhance their school lunch participation.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank the Institut de Sondage Lavialle (ISL) team for the collection of data and all of the families for their cooperation. Financial support: The INCA2 study was carried out and financed by AFSSA, now ANSES. Conflict of interest: Five of the six authors worked at AFSSA during the designing of the survey, the analysing of the data and the article writing. Authorship: C.D. analysed the data and wrote the paper. L.L., S.L., J.-L.V. and D.T. helped to write the paper. G.C.-T., C.D., A.D., L.L., S.L. and J.-L.V. contributed to the design and data collection of the INCA2 survey. All the authors reviewed the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This survey was approved by the CNIL.

Appendix

Details of the twenty-four food groups