The emerging concept of ‘food justice’ describes a social movement and a set of principles. It aligns with the goals of social justice, demanding recognition of human rights, equal opportunity, fair treatment and is participatory and community-specific(Reference Liebenberg1,Reference Loo2) . Its emergence also takes into account the global recognition that the food system is symbiotically linked to public health(Reference Story, Hamm and Wallinga3). This is because of the connectivity that exists between food, health and the environment.

Worldwide farmers produce enough food to feed all citizens(Reference Bahadur, Goretty and Dias4). At the same time a combination of substantial food waste, inadequate food distribution and mass production of over-processed and low-nutritious food. Consequently, hunger is increasing(Reference Lartey, Meerman and Wijesinha-Bettoni5), the prevalence of undernourished people is escalating(6), obesity is reaching epidemic proportions(Reference Lartey, Meerman and Wijesinha-Bettoni5) and public health being negatively impacted by escalating diet-related chronic disease rates. Furthermore, climate change influences agricultural production, and agricultural practices negatively impact the environment(Reference Ericksen, Ingram and Liverman7). This has led to a ‘triple crisis’, whereby obesity, undernutrition and climate change undermine the conditions for human and planetary health(Reference Swinburn, Kraak and Allender8). Food justice is emerging as a powerful mobilising concept for driving social change to address food inequities from a more-than-human perspective(Reference Abram9) – referring to the inseparability of human and natural interactions – but in theory and practice, it is a contested term(Reference Coulson and Milbourne10).

The world is at a critical juncture, as the state of global food insecurity – referring to a lack of access to sufficient and adequate food – increases after remaining virtually unchanged from 2014 to 2019 (FAO 2021). The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 ‘Zero Hunger’ is the human rights catalyst for governments to target food systems and environments to improve people’s access to safe, nutritious and sufficient food by 2030(11). The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights states ‘everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and wellbeing of himself and his family, including food…’. Although not legally binding, many countries endorsed a human rights-based approach to economic, social and cultural rights in 1975(Reference Godrich, Barbour and Lindberg12). However, when it comes to equitable access to healthy, affordable and nutritious food, governments have predominately adopted a needs-based response, such as food relief, rather than a rights-based approach which is community-led(Reference Uvin13). The root causes of food insecurity are multifactorial and tend to include material hardships and inadequate financial resources(Reference Bowden14). The dominant response has focused on government welfare payments and supporting emergency food relief initiatives within the charitable food sector(Reference Godrich, Barbour and Lindberg12,Reference Caraher and Furey15) . Such technical fixes are unlikely to solve food insecurity challenge(Reference Lindberg, McKenzie and Haines16). These technical fixes are primarily focused on issues of food access, reflecting a ‘passive’ welfare ethos, locking people into welfare dependency(Reference Seivwright, Callis and Flatau17). While ‘community’ is understood as the site of the social problem, food insecurity will remain a site of political debate(Reference Everingham18).

The United Nations FAO has a vision for food security, which is when ‘… all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’(19). Consistent with this vision, some governments (e.g. Australia) state that their national goal is to remain one of the most food security nations in the world(20). National food security targets are often met by sourcing food produced under environmentally destructive and exploitative conditions and supported by subsidies and policies that destroy local food producers but benefit agribusiness corporations(Reference Edelman21,Reference Davies22) .

Food system transformation – the radical change needed in our food system to dramatically improve environmental, health and livelihood outcomes – should be informed by timely and robust evidence. The literature on food security, social justice and the food system is extensive and varied, and continually evolving(Reference Clapp, Moseley and Burlingame23). It ranges from assessments and proposed solutions to economic analyses, social and philosophical examinations of food as a human right and social justice issue(Reference Fleetwood24). To transform the food system, there is a call to broaden the scope of food security to go beyond the four well-documented pillars of availability, access, utilisation and stability to recognise sustainability and agency – where agency refers to the capacity of individuals and groups to exercise their voice and make decisions about their food systems – which are critical dimensions of food security and flow directly from the principles of the right to food legal framework(Reference Clapp, Moseley and Burlingame23). The right to food, a legal right protected under human rights law, implies the right of people to feed themselves in dignity(25). Sustainability seeks to achieve an environmentally sustainable food system(Reference Longo26), which refers to how citizens can be empowered to exercise their capacity to make choices about what they eat, the foods they produce, how that food is produced, processed, distributed and their role in participating in policy processes that shape food systems(Reference Clapp, Moseley and Burlingame23,27) .

Agency is at the heart of community participation, which is critical for identifying an alternative future to the dominant food system, and advancing the social change needed to achieve transformation. Community-driven food system transformation, designed to facilitate human rights by promoting food security and addressing food insecurity, is simultaneously tackling the underlying structural determinants of food inequities and engaging in discourses and other local and global actions to confront these injustices(Reference Moragues-Faus28). At this juncture, the concept of food justice has emerged as a powerful mobilising concept for driving such social change.

Food justice has emerged as a response to social inequalities perpetuated by the mainstream food movement in the USA by marginalised communities seeking to address their food needs(Reference Alkon and Agyeman29,Reference Smith30) . To understand what is required to progress food justice – that is, political platforms and policies – more needs to be known about the discursive contributions that the literature is making in this field.

In this study, we investigated the conceptualisation of food justice and explored how community participation is positioned in food justice scholarship. This paper is part of a larger project exploring the practice of food justice in two local communities in an Australian state.

Methods

A scoping review was undertaken to examine the extent of the available evidence and highlight gaps in the existing research which explores food justice. A five-step scoping review protocol(Reference Arksey and O’Malley31) was used to (i) define the research question, (ii) identify the relevant studies, (iii) select the relevant studies, (iv) chart, collate and summarise the data and (v) report the results.

Defining the research question

The aim of this review was to clarify the conceptualisation, use and practice of the term food justice. This review was guided by the following questions: What is the scope of publications on food justice according to country of origin, year of publication and discipline? How is food justice conceptualised with a particular focus on community participation? What is the frequency of research on food justice published in the peer-reviewed literature over time?

Identification of relevant studies

A search of Medline (OVID), Scopus and Web of Sciences was conducted for all available studies preceding September 2020 using the term ‘food justice’ in publication titles and abstracts. The search used the following keywords and query strings for each database: ‘TITLE-ABS-KEY (food justice)’ in Scopus and ‘TS = food justice’ in the MEDLINE and Web of Science Core Collection. We did not restrict the search to specific publication dates or research areas. The reference lists of systematic reviews were searched to ensure that all relevant studies were included. Saturation was achieved when no new studies were identified.

Selection of the relevant studies

All citations were imported to the EndNote™ reference manager and duplicates were removed. Using the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) citations, titles and abstracts were independently screened by two researchers one (SM) and two (LD). Discrepancies were resolved through consensus. Full texts of the included titles and abstracts were downloaded to Endnote citation software(32) and read by both researchers. They were exported to the Covidence Review Software(33), to manage the data screening process, whereby the two researchers undertook a full-text assessment for eligibility. Disagreements on full-text assessments were discussed by the researchers and resolved by consensus to eliminate selection bias.

Table 1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Charting the data

Key data that were extracted included study reference details (title, journal name, authors, discipline of the first author, year of study), study setting (country), study design, study rationale, research question, conceptualisations of food justice and primary outcomes relating to food justice. The disciplines of the first authors and their country of origin were extracted from the websites of their universities or institutes of affiliation and were used to identify the discipline from which the term or concept of food justice was interpreted. The data were exported from Covidence to a Microsoft Excel table to conduct the narrative synthesis.

This study required the identification and interpretation of patterns and themes within the data set; therefore, the Braun and Clark’s six-step thematic analysis process was used to determine the final food justice themes, including familiarisation, coding, iterative theme development, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and writing up(Reference Braun and Clarke34). Braun and Clark’s reflexive thematic analysis approach was applied(Reference Braun and Clarke35,Reference Braun and Clarke36) . The reflexive thematic analysis approach chosen for this study had a post-positivist approach to data analysis. This approach recognises the influence of researchers in interpreting data and encourages researchers to reflect on their influence as they develop and interpret codes(Reference Braun and Clarke34,Reference Braun and Clarke35) .

To ensure immersion, all selected literature was read by researcher one (SM) multiple times, coding all data, and researcher two (LD) double-coded 10 % of the studies(Reference Green, Willis and Hughes37). A comprehensive list of key food justice terms for all included studies was extracted using an inductive approach to coding without the need for a coding framework (Table 3). These terms were analysed and grouped to reflect overarching themes and then labelled using the dominant recurring keyword representing the theme of that group. For example, terms such as food scarcity, food insecurity and hunger were grouped as like-terms, and the concept of food security was then used as a label to represent overarching themes. After one complete coding cycle, all codes and themes were documented, presented and discussed with the research team (SM, LD, DA and FG). The data were then uncategorised, re-coded, re-categorised, meaning checked and corroborated by researchers one and two. New codes and themes were identified during the iterative process. Themes were cross matched against the conceptualisations identified in each of the ninety studies (online Supplementary File 1). Major definitions were summarised to include the frequency of appearance of each term by study (Table 4), growth in the use of the term food justice by year and disciplinary origin (Table 5).

Reporting the results

A description of the study selection process, study design, disciplines, years of publication and geographical distribution of the included studies as well as the conceptualisations of food justice were reported. Throughout this process, data were continually examined to make comparisons, examine contradictions and identify gaps, while keeping the aims of the paper at the front and centre(Reference Braun and Clarke35,Reference Green, Willis and Hughes37,Reference Braun and Clarke38) . The themes were discussed, reviewed, refined and checked by all the team members. Descriptions of some conceptualisations of food justice were insufficient, and interpretations of the terms were not always consistent. By adopting an approach based on conceptualisations of food justice, as well as definitions, the results provided a much broader understanding of how the term food justice was being used and adopted by authors. The results are described and presented as key themes of food justice. It was outside the scope of this review to report the methodological quality of the included studies.

Results

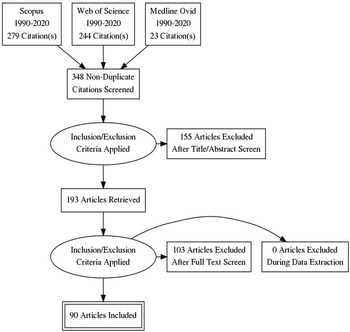

The search yielded 546 records from three databases: Medline (OVID), Scopus and Web of Science. Duplicates were excluded leaving 348 unique records for the analysis. Of the 348 records screened, 155 were excluded as irrelevant. The remaining 193 studies were subjected to a full-text assessment for eligibility, which led to 103 being determined as ineligible based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria in Table 1. The remaining ninety studies were included in the database for data extraction (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram of search process

The scope of studies on food justice

Table 2 provides a descriptive summary of the identified studies on food justice. It identifies the scope of studies by country of origin, year of publication and discipline. Food justice was a highly interdisciplinary and expansive field of research that quadrupled each year after 2015, with most published in 2017. The highest concentration of studies came from high-income countries: the USA, the UK, Canada and Hong Kong. There was a complete absence of the term food justice in other geographical regions and from low- and middle-income countries. Ten disciplines clustered into three fields of knowledge(39) published literature on food justice. The sociology and geography disciplines had the highest number of publications, representing 56 % of peer-reviewed studies and most were based in the USA and Canada. These studies have been associated with civil rights and social movements, the development of community-based approaches through alternative food practices, inequities in food access and environmental impacts. The methodologies were exclusively qualitative with case studies (61 %) examining existing initiatives, organisations and communities (Table 2).

Table 2 Descriptive summary of study characteristics of peer-reviewed publications

Thematic analysis of the conceptualisations of food justice

Five themes of food justice conceptualisation were identified (Table 3). The themes and their frequency of appearance across the ninety publications (which were not mutually exclusive) were as follows: (1) social equity in 89 % of the studies, (2) food security in 79 %, (3) food systems transformation in 56 %, (4) community participation and agency in 66 % and (5) environmental sustainability in 39 %.

Table 3 Themes of food justice conceptualisations and frequency of appearance by study

Within the five identified food justice themes, there were four themes including social equity, food security, food system transformation, and community participation and agency which all aligned with the core principles of social justice: equity, access, justice and rights(Reference Fleetwood24). Environmental sustainability, the fifth category aligned with the core principles of environmental justice, is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people concerning the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies(Reference Burger, Harris and Harper40). Each of the five themes, while interconnected and broadly overlapping, reflect overarching central themes that are more powerful when explicitly stated. The themes and their alignment with social and environmental justice perspectives are discussed below presenting a deeper analysis to broaden the discussion of food justice.

Social equity, the largest category of studies, described persistent challenges to equity in the food system and the existence of structural inequality and discrimination. Terminologies such as structural inequality, exploitation, oppression, and social exclusion affecting marginalised and low-income communities were most prominent. Also prominent within this theme were terms such as racism, class, gender, cultural politics, white privilege, historical trauma and colonisation(Reference Coulson and Milbourne10,Reference Smith30,Reference Guthman41–Reference Siegner, Acey and Sowerwine50) . Health inequalities and disparities are also prominent(Reference Hayes and Carbone43) with a focus on the intersecting issues of policy, health, social justice, economic development and the natural environment(Reference Kaiser, Himmelheber and Miller51,Reference Pugh52) . Such an emphasis suggests that food justice takes a broad social justice perspective and considers how unequal access to healthy food intersects with poor health(Reference Harper, Sands and Angarita Horowitz53). There was a view that the voices of marginalised communities could be amplified by creating opportunities for dialogue with participants and improving health outcomes(Reference Alkon and Norgaard54–Reference Porter58).

Food security, the next largest category of studies, described inequitable access to healthy, affordable and culturally appropriate food and land. Terminology such as poor or unjust access to healthy and affordable food was most prominent, with terms such as food insecurity, food poverty, food apartheid, scarcity, hunger, right to food, food deserts, food sovereignty and community food security also used to imply challenges or solutions to accessing food(Reference Moragues-Faus28,Reference Alkon and Agyeman29,Reference Hayes and Carbone43,Reference Cadieux and Slocum44,Reference Porter47,Reference Alkon and Norgaard54,Reference Mello56,Reference Wekerle59–Reference Noll and Murdock72) .

Food systems transformation was the third largest category of studies. These studies described dysfunctional food systems and called for structural and redistributive changes in the food system. Terminology included transformation, food systems democratisation, power, food bank reform, food policy councils, food governance and policy reform, tackling problems at a local and national level, policy solutions, building coalitions, politicians, and the state, justice (historical, holistic, participative, distributive, representational) and reframing(Reference Coulson and Milbourne10,Reference Cadieux and Slocum44,Reference Sbicca and Myers45,Reference Thompson, Johnson and Cistrunk49,Reference Freudenberg, McDonough and Tsui55,Reference Sbicca61,Reference Tornaghi65,Reference Bedore73–Reference Maughan, Anderson and Kneafsey83) . The hope for food systems transformation focused on increasing food access and dismantling structural inequalities. It was claimed that(84) it is insufficient for states to provide food relief without dismantling structural inequalities; therefore, food access is regarded as the entry point to food systems transformation and not the endpoint(Reference Fanzo, Haddad and Schneider85).

Community participation and agency were the second least represented category and described community rights to participate and engage in food policy decision-making and governance, community resistance to and disruption of the existing corporate food regime and community-led, driven and/or owned food solutions. Terminologies such as participation, advocacy, self-reliance, self-determination, activism, movements and direct action were used to empower the voice of the community(Reference Sbicca and Myers45,Reference Horst46,Reference Tornaghi65,Reference McKinney and Kato78,Reference Bradley and Galt86–Reference Poulsen89) . Also terminology such as alternative food networks, urban planning and non-commodification of the food system represented opportunities for the community to engage in food policy decision-making and governance(Reference Cadieux and Slocum44,Reference Mello56,Reference Werkheiser and Noll75,Reference Burga and Stoscheck79,Reference Sandover82,Reference Walker90–Reference Aptekar and Myers93) . Urban agriculture, community gardens, farmers’ markets, community and school-led, owned and controlled food solutions all provide opportunities for communities to be self-reliant, self-sufficient, empowered to take control and make decisions about their own food systems(Reference Siegner, Sowerwine and Acey48,Reference Siegner, Acey and Sowerwine50,Reference Porter, Conner and Kolodinsky67,Reference Sandover82,Reference Walker90,Reference Aptekar and Myers93–Reference Porter97) .

Finally, environmental sustainability was the smallest category in the study. These studies described the need for food systems that minimise resource depletion and unacceptable environmental impacts. Terminologies such as climate change, human and environmental health, environmental sustainability and environmental justice were most prominent. While environmental concerns in the food justice literature were less prominent, their frequency of appearance increased from 2015(Reference Coulson and Milbourne10,Reference Moragues-Faus28,Reference Hayes and Carbone43,Reference Cadieux and Slocum44,Reference Kaiser, Himmelheber and Miller51–Reference Alkon and Norgaard54,Reference Wekerle59,Reference Levkoe60,Reference Tornaghi65,Reference Thompson, Cochrane and Hopma71,Reference Bedore73,Reference Barron77–Reference Burga and Stoscheck79,Reference Maughan, Anderson and Kneafsey83,Reference Walker90,Reference Kato98–Reference Gordon and Hunt102) .

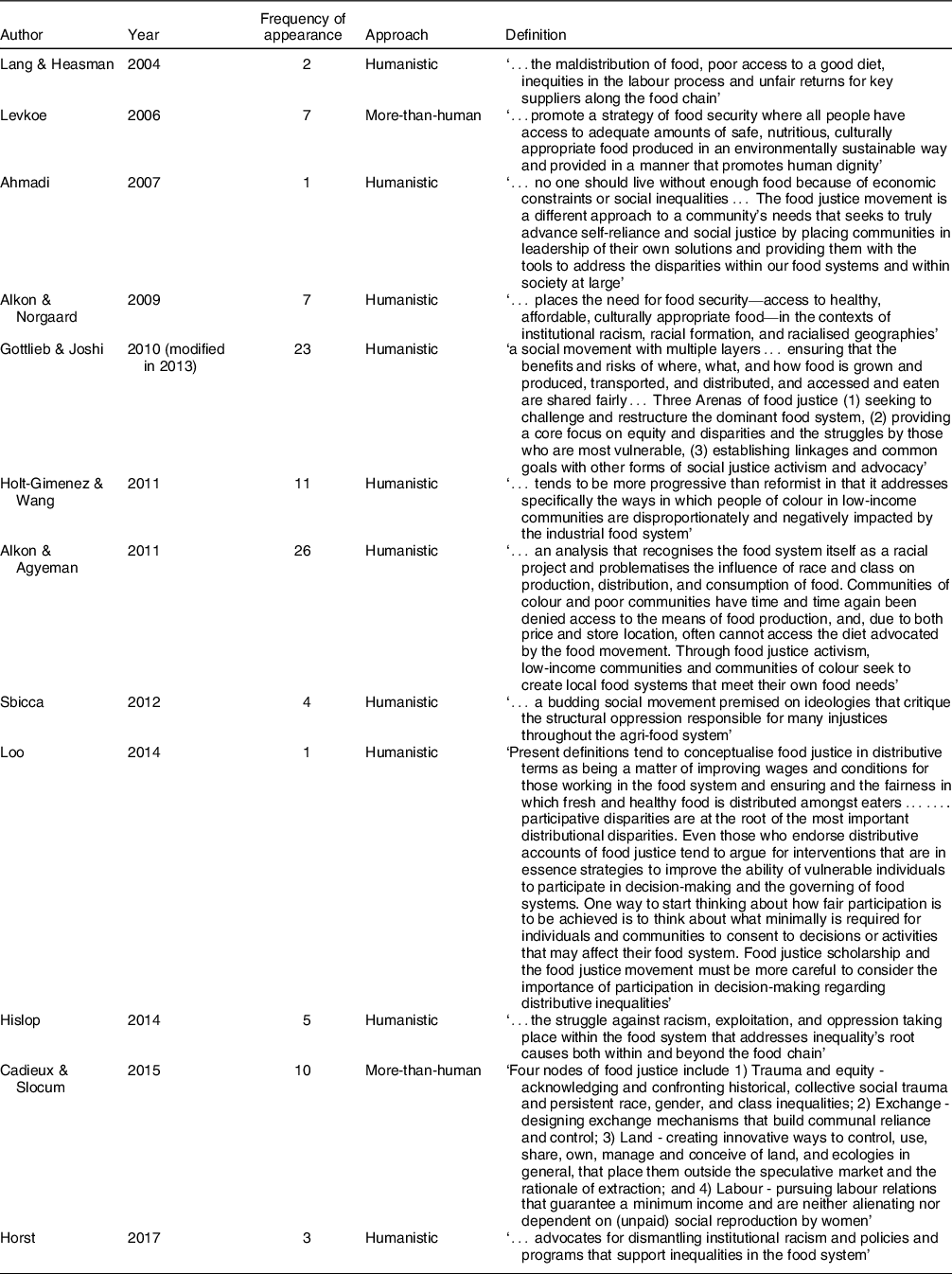

Definitions of food justice

The major definitions of food justice were summarised, including the frequency of their appearance. Twelve definitions were identified, the two most frequently cited being Gottlieb and Joshi (developed in 2010 and expanded in 2013), and Alkon and Agyeman (developed in 2011). Gottlieb and Joshi’s(Reference Gottlieb and Joshi103) definition was cited twenty-three times (including the original publication in which it appeared) and was reflected in four of the five identified themes (social equity, food security, food systems transformation and community participation and agency). Alkon and Agyeman’s(Reference Alkon and Agyeman29) definition was cited twenty-six times and reflected the same four food justice themes. The next most frequently cited definitions were those of Holt-Gimenez and Wang(Reference Holt-Gimenez and Wang74) which was cited eleven times, Cadieux and Slocum(Reference Cadieux and Slocum44) cited ten times, Levkoe(Reference Levkoe60) cited seven times and Hislop(Reference Hislop63) cited five times (Table 4). Based on an analysis of all twelve definitions, two distinct approaches to food justice were identified. The first, the ‘humanistic’ approach – referring to humans being placed front and centre – was reflected in ten definitions and was underpinned by the social justice principles of dignity, self-determination, equity, access, fairness and greater participation. The second ‘more-than-human’ approach was reflected in two definitions(Reference Cadieux and Slocum44,Reference Levkoe60) and combined social and environmental justice principles to include issues of distribution, participation and procedure, recognition and capabilities.

Table 4 Key definitions of food justice by author, year and frequency of appearance

The frequency of research on food justice over time

The use of the term food justice has grown since 2004, with an expansion in the five identified food justice themes from 2015 (Table 5). While all themes have increased in prominence, there has been a specific upward trend in themes addressing food systems transformation, community participation and agency, and environmental sustainability.

Table 5 Growth in food justice literature by year, discipline cluster and category

AS, Applied Science; SS, Social Science; H, Humanities; PH, Public Health.

Discussion

This scoping review found that, since 2004, the majority (77 %) of food justice studies, using the term, quadrupled each year from 2015 with 2017 being the most prolific publication year. The spike in publications can be linked to the momentum fostered by the official adoption of the UN SDG in late 2015(11), the concurrent general rise in food studies scholarship and the ‘social justice turn’ – adoption of an anti-oppressive stance – in the broader social and environmental literature. Publications on food justice came from the USA, Canada, the UK and Hong Kong (Tables 2 and 5). This distribution represents a long history of social justice activism in these countries that has been led by marginalised groups tackling inequality, poverty and injustice, in which food has often played an important role(Reference Cadieux and Slocum44,Reference Ornstein104) . The limitation of this distribution does not mean that social justice activism for food system transformation has not occurred in other countries. Conversely, this may mean that relevant literature in other languages has not been included due to the exclusion of non-English language literature in our exclusion criteria.

The multidisciplinary body of food justice research reported in this scoping review incorporates contributions from ten disciplines organised into three academic clusters or fields of knowledge. Within the social sciences publications, the discipline of sociology (47 %) was the most prolific, followed by geography (44 %) within the applied sciences, and public health (including nutrition) (9 %). From over 40 000 journals searched, 348 papers were reviewed, and several academic disciplines were not identified or had limited presence, including agricultural science, economics, management, law and philosophy. These disciplines are active and influential in food policy debates and discussions related to food security; curiously, they have yet to engage with the food justice debate. Conversely, these disciplines may have engaged and been published in different journals or formats, such as essays, rather than peer-reviewed journals. Further research is required to understand the reasons for this.

Since 2015, there has been a shift in the conceptualisations of food justice. The five themes identified in this review may be attributable to a movement towards challenging and restructuring the dominant food system in-line with global expectations to deliver progress on all seventeen SDG(105). The underlying premise of the SDG vision rests on principles of human rights and social justice that emphasise dignity, self-determination, equity, access, fairness, and greater participation(Reference Rawls106), and principles of environmental justice that emphasise distribution, participation, and procedure, recognition, and capabilities(Reference Coolsaet107).

Challenging and calling for the dominant food system to be restructured may also arise from a tendency to link the construct of food justice with other forms of social justice, such as activism and advocacy(Reference Coulson and Milbourne10). More recently, published literature indicates the need for further community participation and agency. While such actions align with human rights-based approaches to food security(108), this alone is unlikely to change policy, systems and practice. An integrated food systems approach requires a more-than-human rights-based approach that implies the inseparability of human and natural interactions and the right of people to feed themselves with dignity(Reference Abram9,25) .

Broadening the view of food justice

The scoping review identified that food justice has been conceptualised mostly in distributional terms in the definitions of Lang and Heasman(Reference Lang and Heasman109), Levkoe(Reference Levkoe60), Alkon and Norgaard(Reference Alkon and Norgaard54), Gottlieb and Joshi(Reference Gottlieb and Joshi103), Holt-Gimenez and Wang(Reference Holt-Gimenez and Wang74), Hislop(Reference Hislop63), Cadieux and Slocum(Reference Cadieux and Slocum44) and Horst(Reference Horst46) (Table 4). These conceptualisations reflect the elements of the World Food Summit’s (1996) definition of food security, which was further refined in the FAO 2002 definition given at the beginning of this study. At its core, the FAO definition embraces a social justice approach using distributive justice – the fair allocation of resources – as a mechanism to get food to people who lack access. In practice, this has a range of positive and pernicious effects. The focus on food distribution responsibilises individuals and households to meet their own food security needs in the first instance and encourages interventions such as emergency food relief practices in specific instances when individuals and households fail to do so(Reference Caraher and Furey15). This system ‘feeds on itself’, as emergency food relief distribution practices then enable the structural factors underpinning the original inability of the household to meet its food security needs – lack of financial resources, failed land reform, poor food quality, low levels of community empowerment and food inappropriateness – to be downplayed or ignored.

This scoping review also found that food justice was increasingly conceptualised in procedural terms. Procedural justice moves beyond distribution and centres on participation in the decision-making process or policies used to make allocation decisions and manage resources, suggesting that participative disparities are at the root of the most important distributional disparities(Reference Cohen110). This approach challenges the structural accounts of people being at the mercy of law, politics and economics. Instead, people are repositioned as active agents capable of ascribing freedom and responsibility and facilitating change. This literature considers humanistic procedural justice emancipatory because it offers less powerful stakeholders a mechanism to challenge the corporatisation of food systems and the harmful technological fixes that are considered detrimental to the environment.

An example of this procedural emancipatory justice approach is the Global People’s Summit on Food Systems(111), which was launched as a counter-summit to the UN Food Systems Summit in 2021(105). The Global People’s Summit drew worldwide attention to the vulnerabilities and lack of sustainability inherent in the current global commodified export-based food system(Reference Canfield, Anderson and McMichael112). However, in the food justice literature, the Summit’s identified social and environmental concerns, under the broad concept of ‘food sovereignty’, are not currently heavily weighted in the dominant conceptions of food justice identified in this scoping review. Food sovereignty embraces a linked social–economic–environmental conception of justice and views local food systems as the most appropriate way to tackle sustainable food security. It responsibilises communities (local, state and national governments) by ensuring food security, which is understood as a fundamental political and economic right, and seeks to empower those who have failed by their communities to take affirmative action(Reference Mayer and Anderson113). This scoping review argues that distributional inequalities often result from participatory inequalities(Reference Fraser114,Reference Schlosberg115) .

An emerging opportunity for community participation and agency

This review supports the view of many food justice theorists(Reference Loo2,Reference Cadieux and Slocum44,Reference Alkon, Bowen and Kato116–Reference Sbicca118) of a paradigmatic shift in the conceptualisation of food justice over the past two decades. The concept of food justice has expanded beyond its initial relatively limited meanings predominately underpinned by the social justice principles of the need to respond to food insecurity. Food justice now references multiple justice themes, including procedural, emancipatory and humanistic conceptions that obligate governments (i.e. local, state and national governments) to be primarily responsible for ensuring food security as a fundamental political-economic right. The approach is linked to enabling local communities to achieve food justice through empowerment which enables participation and respects agency(27). Local action by people with lived experience of food insecurity plays a vital role in addressing the root causes of food injustices throughout the food system and ensuring that society works towards food justice for all(Reference Sbicca118). Furthermore, the concept of food justice acknowledges and welcomes ‘other actors’ into the food system, as these are required to address various structural barriers to ensure that the rhetoric of food justice becomes a reality.

If governments and communities can work together, there are new opportunities to use food justice and rights language when conveying food security information; embrace grass roots advocacy to raise awareness and contextualised understandings of the issue; create dialogue among community participants to advocate fair food policies that affect them; develop community leaders to be experts in healthy and sustainable food systems; provide resources that community participants need to succeed in such as policy-relevant scientific evidence; bring the voices of underrepresented groups into the conversation and provide resources and skills. At the policy level, opportunities exist for evaluating policy changes that document benefits and limitations, and integrated food justice and rights into government frameworks and community projects(Reference Godrich, Barbour and Lindberg12,Reference Freudenberg, McDonough and Tsui55) .

While different stakeholders are likely to continue emphasising the specific themes of food justice to achieve different outcomes, it is useful to place this in a broader context. For example, some groups aiming to improve food justice outcomes in local municipal regions, where race and ethnic issues are central defining features, are likely to place greater emphasis on social equity. For others who seek to prevent obesity and diabetes and respond to the rapidly increasing rates of chronic disease, high-level policy reform linked to media advertising, food literacy and sugar taxes will come into focus. However, regardless of the specific focus, stakeholders must place their food justice conceptions within a broader consideration of the structural and environmental factors in play. Urbanisation, wage stagnation and the impacts of COVID-19 on the one hand and climate change, deforestation and biodiversity loss must be considered in any discussion of the food system and its link to social issues, such as public health.

Definitions of food justice vary, which means that the practice of food justice could be challenging to execute(Reference Kato98). The interpretation of justice as it relates to food production, distribution and consumption is multifaceted and complex(Reference Anderson119). Perhaps the fragmented nature of food justice is its strength, with its potential to be flexible in implementing local solutions to global issues(Reference Wekerle59). Food justice is only now beginning to mature to embrace a holistic and structural view of the food system that understands healthy food as a human right and acknowledges the need to address various structural barriers to that right(Reference Coulson and Milbourne10,120) . Community participation, agency, activism and empowerment must be part of any food justice plan for self-sufficiency and sustainability.

Limitation

This review had three limitations. First, it limited the search term to ‘food justice’ and Boolean strings such as ‘food AND justice’ were not applied. The search strategy, therefore, did not encompass all terms related to ‘food justice’ such as the right to food, food sovereignty, food security or food democracy studies. This enabled the authors to keep the study closely focused on the concept of ‘food justice’ to generate a manageable database. Second, the search was limited to three databases which, although larger, were not comprehensive. Taken together, these limitations likely overlooked relevant studies. Despite these limitations, the search strategies yielded many studies in which ‘food justice’ and related terms were the focus of the review, and the existence of considerable duplication across the databases indicates that the studies were drawn from a larger, shared sample. Third, there is an opportunity for further development of the five food justice themes, given their close interlinkage. Future reviews could encompass other conceptualisations and the connections between them and additional databases, to draw a wider picture of the relationships between marginalised communities and food injustice.

Conclusion

Despite its almost 20-year history, the parameters of food justice continue to evolve, with limited consensus in the literature on what food justice is, making it difficult for communities to mobilise for transformative food system changes. Food justice is a multidisciplinary concept that is rooted in human rights and justice. Most commentators embrace a ‘humanistic’ position to conceptualise and define food justice by drawing on the principles of social justice. This discursive position is likely to sustain food banks and food relief approaches to food security. A less prominent ‘more-than-human’ conception of food justice has recently emerged to combine social and environmental justice principles in a quest for human well-being and global sustainability. Combining the social justice principles of dignity, self-determination, equity, access and participation with environmental justice principles that emphasise participation, distribution and procedure, recognition and capabilities enables a broader and more contemporary conception of food justice. The broader conceptualisation of food justice can be used as a powerful mobilising concept for a range of stakeholders to contribute to food system transformation discussions and planning by advocating the health benefits of food justice. Furthermore, it can inform calls for a more integrated approach to healthier and more just local and national food policies, systems and practices that address obesity, undernutrition, climate change and other environmental issues that decimate human and planetary health.

Community participation and agency in food justice decision-making is critical for transformative change towards a healthy, sustainable and more just food system.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge the King and Amy O’Malley Trust. Financial support: Funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. Authorship: S.M. is the first and corresponding author contributing 60 % to the conception, design, planning, execution and preparation of the paper. L.D. contributed 20 % to the conception and design of the paper, contributed to data extraction and synthesis and edited a significant part of the paper. F.G. contributed 10 % to the conception and design of the paper and edited a significant part of the paper. D.A. contributed 10 % to the conception and design of the paper and edited a significant part of the paper. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethical approval was not required because this study retrieved and synthesised data from already published studies.

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organisation or entity with any financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980023000101