The history of humanity has been marked by successive shifts in the dietary patterns and nutritional status of populations(Reference Popkin, Adair and Ng1). These shifts characterise the so-called nutrition transition(Reference Popkin, Adair and Ng1–Reference Rivera, Pedraza and Martorell3). Developing countries have experienced a rapid nutrition transition in the past decades, associated with rapid economic development and urbanisation, and consequently with declines in physical activity and major changes in the food system such as the increased availability and access to highly processed foods(Reference Popkin, Adair and Ng1). This scenario has resulted in an overlap of nutrition transition stages, creating conditions for undernutrition forms to coexist with overweight and obesity, a phenomenon known as double burden of malnutrition (DBM), which can occur at individual, household and population levels and across life-course(Reference Conde and Monteiro2–5).

Socio-economic conditions are the main structural determinants of malnutrition in all its forms(5,Reference Wells, Sawaya and Wibaek6) , which is an important problem in countries with substantial social inequality(Reference Perez-Escamilla, Bermudez and Buccini7). Brazil is one of the countries with the highest income inequality rates, despite considerable advances in reducing poverty and improving the population socio-economic conditions in the past decades(Reference Medeiros8). Extreme poverty decreased by more than half, from 8·1 to 3·1 %, whereas the poverty rate decreased even more, from 22·8 to 7·9 % between 2001 and 2013(Reference Jannuzzi, Sousa, Vaz, Campello, Falcão and Costa9). Despite the decreases in these rates and an accumulation of public policies and investments that resulted in benefits for the health of the Brazilian population, considerable challenges persist(Reference Victora, Aquino and Leal10).

Nationwide representative surveys have detected a substantial reduction in childhood stunting prevalence from 37 to 7 % between 1974 and 2007(Reference Conde and Monteiro2). The prevalence of overweight remained stable at 6–7 % during this period(Reference Conde and Monteiro2). However, more recent studies have demonstrated that overweight is increasing among children, including those in the poorest strata(11,Reference Gonçalves, Barros and Buffarini12) . Trends in children enrolled in the Bolsa Família Program (BFP), the world’s largest conditional cash transfer programme targeting families living in poverty and extreme poverty in Brazil, show a reduction from 14·2 to 12·2 % in the prevalence of stunting and an increasing trend from 12·5 to 13·1 % in the prevalence of overweight between 2008 and 2012(11).

This increasing burden of overweight along with a still existing burden of stunting among poor children suggests that Brazil faces a DBM in this population. Recent study shows that the DBM has also increased in the poorest low- and middle-income countries, mainly due to overweight and obesity increases(Reference Popkin, Corvalan and Grummer-Strawn4). The DBM is united by shared drivers and solutions, which include multifactorial aspects, and therefore offers a unique opportunity for integrated nutrition action(Reference Hawkes, Ruel and Salm13). However, very few studies to date have simultaneously analysed the shifting prevalence of under- and overnutrition(Reference Popkin, Corvalan and Grummer-Strawn4,Reference Tzioumis, Kay and Bentley14,Reference Min, Zhao and Slivka15) . These outcomes have usually been studied separately, making difficult to disentangle the understanding of DBM.

The coexistence of prevalent and paradoxical forms of malnutrition among the most vulnerable socio-economic strata of the population makes Brazil a potential laboratory for investigating socio-economic determinants associated with the nutritional status in early childhood. Using a novel approach, the study aimed (i) to describe the shifts towards different scenarios resulting from the prevalence of stunting and overweight in Brazilian municipalities, based on aggregated data of children enrolled in the conditional cash transfer Bolsa Família and (ii) to analyse municipal-level socio-economic factors associated with these scenarios.

Methods

Study design and population

This longitudinal ecological study combined the analysis of multiple observation units and temporal trend analysis. Panel data of the prevalence of stunting and overweight among children under 5 years of age enrolled in BFP in Brazilian municipalities from 2008 to 2014 were analysed. Municipalities were analysed based on yearly repeated observations available in administrative databases in the public domain. Of the 5570 existing municipalities in Brazil, 4443 were included in the study. Sixty-three municipalities did not have available data for all years, and 1064 had very few children (< 30) with anthropometric measurement in each studied year.

BFP is a conditional cash transfer programme that was implemented in Brazil in 2003, targeting families living in poverty (monthly per capita income from R$ 85/US$ 16 to R$ 170/ US$ 32) or extreme poverty (monthly per capita income up to R$ 85/US$ 32). Through direct cash transfer and monitoring of education and health conditions, BFP seeks to combat hunger, poverty and other forms of deprivation, to promote food and nutrition security and access to public services, particularly health care, education and social assistance(16). The amount received by each family varies according to its monthly per capita income, number of individuals under 17 years old and presence of pregnant or breast-feeding women. Monitored conditions include vaccinations, nutrition surveillance of children under 7 years of age, prenatal visits of pregnant women and minimum school attendance of 85 % for children and adolescents 6 to 15 years old and 75 % for adolescents 16 and 17 years old(16). BFP has shown to successfully improve several child health outcomes, such as anthropometric indicators(Reference Paes-Sousa, Santos and Miazaki17), mortality rates(Reference Rasella, Aquino and Santos18) and the use of health care services and growth monitoring(Reference Shei, Costa and Reis19). In addition, PBF has been recognised for its large coverage of the poor Brazilian population. In February 2020, the programme reached 96 % (over 13·2 million families) of the eligible poor families(20). Thus, BFP beneficiaries represent a very large proportion of the socio-economically vulnerable population in Brazil.

Data sources

Municipal-level data on the nutritional status of children under 5 years of age enrolled in BFP were obtained from the Food and Nutrition Surveillance System (Sistema de Vigilância Alimentar e Nutricional – SISVAN-Web) public reports(21). Anthropometric data (weight and height) are collected twice per year by community health workers and family health teams, as part of the nutrition surveillance of children enrolled in BFP and entered into the SISVAN-Web database at the end of each term, i.e. June (first term) and December (second term). However, the system selects only the latest available measure in the year of each individual to aggregate data at municipal level and generate the annual reports on nutritional status(22). The number of children enrolled in the programme nationwide for whom data were recorded increased from 2·8 million in the first term of 2008 to 4·6 million in the second term of 2017(23). For the nutritional status assessment of children under 5 years old, SISVAN-Web provides information on height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-height and BMI-for-age, which are analysed using the WHO Anthro software/macro and quality checks and according to WHO Child Growth Standards and cut-off points(24). Guidelines for the collection and analysis of anthropometric data in health services have been standardised by SISVAN(25).

Demographic and socio-economic data were obtained at municipal level from the 2000 and 2010 Demographic Censuses of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE), available at the IBGE Automatic Retrieval System (Sistema IBGE de Recuperação Automática – SIDRA)(26), Department of Informatics of the Unified Health System (Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde – DATASUS) TabNet tool(27) and Atlas of Human Development in Brazil, developed by the United Nations Development Programme in partnership with Brazilian institutions(28). Information on municipal coverage of public health policies, such as the Family Health Strategy, were obtained from DATASUS e-Gestor public reports(29).

Dependent variable

The prevalence of stunting (height-for-age z-score – HAZ < –2 sd) and overweight (weight-for-height z-score–WHZ > +2 sd) among children enrolled in BFP, obtained from SISVAN-Web reports, was categorised according to the new prevalence thresholds formulated by the WHO-UNICEF Technical Expert Advisory Group on Nutrition Monitoring(Reference De Onis, Borghi and Arimond30). These thresholds were established in relation to the degrees of deviation from normality as defined by the WHO Child Growth Standards, making their use appropriate and advantageous to describe both national and subnational populations according to levels of severity of malnutrition(Reference De Onis, Borghi and Arimond30).

Based on this classification system, a polytomous four-category variable was created by combining the prevalence of stunting and overweight to characterise nutritional scenarios, such as DBM, where under- and overnutrition coexist in different levels of severity:

-

No burden: very low-to-medium prevalence of stunting (< 20 %) and very low-to-medium prevalence of overweight (< 10 %);

-

Stunting burden: high and very high prevalence of stunting (≥ 20 %) and very low-to-medium prevalence of overweight (< 10 %);

-

Overweight burden: very low-to-medium prevalence of stunting (< 20 %) and high and very high prevalence of overweight (≥ 10 %);

-

Double burden: high and very high prevalence of stunting (≥ 20 %) and high and very high prevalence of overweight (≥ 10 %).

Independent variables

Demographic and socio-economic data at municipal level were first selected based on the literature on child malnutrition drivers(5,Reference Black, Victora and Walker31,Reference Gillespie, Haddad and Mannar32) and social determinants of health(Reference Marmot, Friel and Bell33). A correlation matrix of all available variables was obtained. Only the variables with weak-to-moderate correlation coefficient (r < 0·5) were considered in the analyses: urban population – % of the population residing in urban areas(27); gross domestic product (GDP) per capita – total sum in Brazilian real (R$) of all final goods and services produced divided by the municipality’s population(26); expected years of schooling – mean number of years of schooling a generation of children entering school will have completed by age 18 if the current patterns maintain throughout their schooling life(28); unemployment rate% of the population over 16 years old out of work(27); Family Health Strategy coverage% of the population covered by Family Health Strategy teams, considering a parameter of 3450 individuals covered per team(29) and household crowding% of the population residing in households with more than two individuals/bedroom(28). For demographic and socio-economic variables with years not covered by the demographic censuses, values were estimated by linear interpolation and extrapolation from the 2000 and 2010 census data. Variables were also categorised as tertiles or according to reference values when available, such as Family Health Strategy coverage(Reference Aquino, de Oliveira and Barreto34). Further information about these variables can be found in online supplementary material, Supplementary Table 1.

Data processing and statistical analysis

Data were processed and analysed using Stata version 15.1 (Stata Corporation). For descriptive analysis, the annual prevalence of stunting and overweight was calculated, analysed according to geographic region and population size and categorised according to the WHO-UNICEF new prevalence thresholds. The proportion of municipalities in each nutritional scenario was also calculated annually. Demographic and socio-economic variables were described using measures of central tendency and dispersion.

Multinomial logistic regression models with fixed effects were conducted, using the femlogit command available in Stata(Reference Pforr35), to test the associations between socio-economic variables and the different nutritional scenarios in the municipalities across all time periods. These models allow to consistently estimate effects of time-varying regressors on the log-odds of multinomial outcomes when time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity is present(Reference Pforr35). In our study, time-invariant heterogeneity could represent unobserved characteristics of the municipality, such as geographical, historical, socio-cultural or socio-economic characteristics, which did not change during the period of the study. This attractive feature is accomplished by using only within-individual variation to estimate the regression coefficients.

Crude models were fit to estimate the association of each socio-economic variable separately with the nutritional scenarios. Adjusted multivariate model was fit based on the backward stepwise regression approach. We started with a full (saturated) model, including all socio-economic variables, and then we gradually removed one variable at each step to find a reduced model that best explained the data. Akaike and Bayesian information criteria were used to select the adjusted model. All crude and adjusted models were fit with dummy variables for each analysed year. Estimates were interpreted based on the adjusted OR (aOR) and their corresponding 95 % CI since they are the most feasible option available to interpret fixed-effects logistic regression models(Reference Pforr35).

Results

Of the 4443 municipalities included in the study, 1599 (36·0 %) were from Northeast, 1372 (30·9 %) from Southeast, 693 (15·6 %) from South, 421 (9·5 %) from North and 358 (8·1 %) from Central-West region of Brazil. Municipalities with population size ≤ 20 000 and > 100 000 habitants represented 65·43 % (n 2907) and 6·10 % (n 271), respectively. When compared with other relevant characteristics, the 4443 municipalities included in the study (Table 1) were generally similar to all existing municipalities in the country (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 2).

Table 1 Demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the Brazilian municipalities included in the study, 2008–2014 (n 4443)

IQR: inter-quartile range; FHS: Family Health Strategy; GDP: gross domestic product.

* Variables estimated by linear interpolation and extrapolation from 2000 and 2010 demographic census.

The mean prevalence of stunting among children enrolled in BFP decreased from 14·2 % in 2008 to 12·7 % in 2014 and the mean prevalence of overweight increased from 17·2 % to 18·4 % (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Figure 1). Decreasing trends in the mean prevalence of stunting and increasing trends in the prevalence of overweight were also observed in all geographic regions (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Figure 2) and population sizes (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Figure 3).

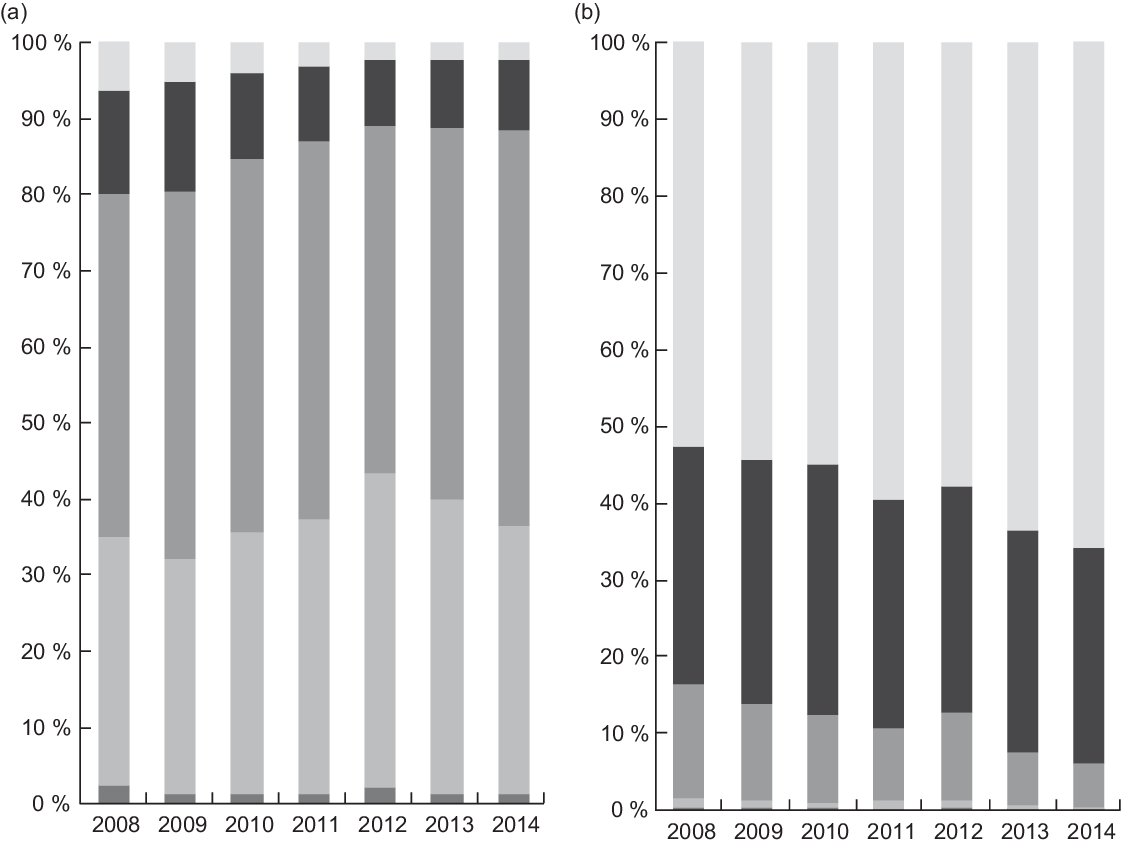

According to the WHO-UNICEF prevalence thresholds (Fig. 1), the rate of stunting was low (2·5–9·9 %) or medium (10–19·9 %) in most Brazilian municipalities. The proportion of municipalities shifting towards low and medium rates of stunting increased by 2·7 and 6·8 %, respectively. In turn, the prevalence of overweight was high (10–14·9 %) or very high (≥ 15 %) in most municipalities, with an increasing trend in the very high range from 52·8 to 65·9 %.

Fig. 1 Frequency of municipalities according to the prevalence thresholds# for stunting (a) and overweight (b) in children enrolled in the Bolsa Família Program, Brazil, 2008–2014 (n 4443). #WHO–UNICEF Technical Expert Advisory Group on Nutrition Monitoring(25). Stunting (a) ![]() , Very low (< 25 %);

, Very low (< 25 %); ![]() , low (2·5–9·9 %);

, low (2·5–9·9 %); ![]() , medium (10–19·9 %);

, medium (10–19·9 %); ![]() , high (20–29·9 %);

, high (20–29·9 %); ![]() , very high (≥ 30 %). Overweight (b)

, very high (≥ 30 %). Overweight (b)![]() , Very low (< 2·5 %);

, Very low (< 2·5 %); ![]() , low (2·5–4·9 %);

, low (2·5–4·9 %); ![]() , medium (5–9·9 %);

, medium (5–9·9 %); ![]() , high (10–14·9 %);

, high (10–14·9 %); ![]() , very high (≥ 15 %)

, very high (≥ 15 %)

The percentage of municipalities experiencing DBM decreased from 18·0 % in 2008 to 10·9 % in 2014 (Fig. 2). The rate of the scenario defined as stunting burden decreased from 1·9 to 0·5 % while overweight burden increased by 17·2 %, from 65·8 to 83·0 %. Lastly, the prevalence of the scenario characterised as no burden decreased from 14·4 to 5·6 %.

Fig. 2 Shifts towards stunting, overweight and double burden scenarios among children enrolled in Bolsa Família Program in Brazilian municipalities, 2008–2014 (n 4443). No burden: very low-to-medium prevalence of stunting (< 20 %) and overweight (< 10 %). Stunting burden: high and very high prevalence of stunting (≥ 20 %) and very low-to-medium prevalence of overweight (< 10 %). Overweight burden: very low-to-medium prevalence of stunting (< 20 %) and high and very high prevalence of overweight (≥ 10 %). Double burden: high and very high prevalence of stunting (≥ 20 %) and overweight (≥ 10 %). ![]() , No burden;

, No burden; ![]() , stunting burden;

, stunting burden; ![]() , overweight burden;

, overweight burden; ![]() , double burden

, double burden

The proportion of urban population increased from 63·9 % in 2008 to 66·7 % in 2014. The GDP per capita almost doubled during the analysed period, increasing from R$ 9600 to 17 400, i.e. by 81·9 %. The number of expected years of schooling exhibited an increasing trend (8·4 %). Family Health Strategy coverage, the main primary health care policy in Brazil, increased from 78·3 to 86·6 %. In turn, the median rate of household crowding decreased from 29·7 to 21·6 %. The median unemployment rate showed a similar decreasing trend from 7·6 to 5·2 % (Table 1).

The crude and adjusted models for the associations between independent variables and nutritional scenarios are described in Table 2. Because fixed effects approach requires observations with time-variant data, only 2670 municipalities were included in the models. According to the adjusted model, the odds of stunting burden were significantly lower for the municipalities in the second tertile of the expected years of schooling variable (aOR 0·40, 95 % CI 0·21, 0·76) and higher for the municipalities in the second tertile of the overcrowding variable (aOR 5·11, 95 % CI 1·02, 25·41) compared with the municipalities in the first tertile. The odds of the scenario defined as overweight burden were progressively higher for the municipalities with higher GDP per capita (second tertile: aOR 1·36, 95 % CI 1·11, 1·33; third tertile: aOR 1·45, 95 % CI 1·08, 1·09) and gradually lower for those with higher unemployment rates (second tertile: aOR 0·77, 95 % CI 0·63, 0·92; third tertile: aOR 0·60, 95 % CI 0·45, 0·80). The odds of DBM (+%ST +%OW) were progressively higher for the municipalities with higher GDP per capita (second tertile: aOR 1·38, 95 % CI 1·06, 1·79; third tertile: aOR 2·28, 95 % CI 1·51, 3·45), progressively lower for those with larger expected years of schooling (second tertile: aOR 0·61, 95 % CI 0·46, 0·80; third tertile: aOR 0·57, 95 % CI 0·38, 0·85) and lower for those in the tertile with the highest unemployment rate (aOR 0·63, 95 % CI 0·42, 0·93).

Table 2 Crude and adjusted models* for the association of demographic and socio-economic characteristics with scenarios of stunting, overweight and double burden among children enrolled in the Bolsa Família program in Brazilian municipalities, 2008–2014

aOR: adjusted OR; FHS: Family Health Strategy; GDP: gross domestic product.

* Multinomial logistic regression models with fixed effects.

† Model adjusted with dummy variables for each year.

‡ No burden (reference category): very low-to-medium prevalence of stunting (< 20 %) and overweight (< 10 %). Stunting burden: high and very high prevalence of stunting (≥ 20 %) and very low-to-medium prevalence of overweight (< 10 %). Overweight burden: very low-to-medium prevalence of stunting (< 20 %) and high and very high prevalence of overweight (≥ 10 %). Double burden: high and very high prevalence of stunting (≥ 20 %) and overweight (≥ 10 %).

Discussion

This longitudinal ecological study aimed to investigate the shifts towards under- and overnutrition scenarios and their associated socio-economic factors in Brazilian municipalities, based on aggregated data of children under 5 years old enrolled in BFP from 2008 to 2014. The results point to a decreasing trend in stunting rates and an increasing trend in overweight rates. However, the data show that most of the municipalities still had moderate levels (10–19·9 %) of stunting, according to the WHO-UNICEF new prevalence thresholds(Reference De Onis, Borghi and Arimond30). Concomitantly, most municipalities also exhibited high and very high rates of overweight (≥ 10 %), with an increasing trend in the very high prevalence range (≥ 15 %) over time.

Four nutritional scenarios resulting from the combination of stunting and overweight prevalence thresholds were analysed in our study. This novel approach considers that under- and overnutrition forms can coexist in different levels of severity, and thus offers a unique opportunity to identify shared drivers of both under- and overnutrition and to find integrated solutions(5,Reference Hawkes, Ruel and Salm13) . The predominant scenario found in the municipalities was overweight burden, which increased by 17·2 %, from 65·8 to 83·0 %. The DBM scenario ranked second in prevalence; however, it decreased from 18·0 to 10·9 %. The least prevalent scenario, stunting burden, decreased from 1·9 to 0·5 %.

These findings seem to reflect a critical and advanced nutrition transition stage in Brazil, where predominant scenarios point shifts towards a decreasing burden of stunting and DBM and an increase in overweight and obesity in the most socio-economically vulnerable population. A report of the recent Lancet Series on the double burden of malnutrition(Reference Popkin, Corvalan and Grummer-Strawn4) shows that severe levels of DBM have shifted to the poorest low- and middle-income countries, especially in the south and east Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, while the number of upper-income low- and middle-income countries with a DBM has decreased.

Multivariate polytomous analysis was conducted to elucidate the socio-economic and demographic determinants associated with the different nutritional scenarios. The results from adjusted models indicate that the odds of overweight burden and double burden in the municipalities increased with higher GDP per capita and decreased with higher unemployment rates. The odds of stunting burden and double burden decreased with higher expected years of schooling. Lastly, the odds of stunting burden increased with household crowding.

Our findings are consistent with those of other studies that show increased rates of overweight/obesity alone or combined with undernutrition as GDP increases(Reference Popkin, Adair and Ng1,Reference Egger, Swinburn and Islam36) . This association is related to rapid economic development, urbanisation and globalisation, which have greatly contributed to shifts in the diet and physical activity patterns in low- and middle-income countries, especially in developing nations such as Brazil(Reference Popkin, Adair and Ng1,Reference Conde and Monteiro2) . Changes in the economic structure, the liberalisation of international food trade and foreign direct investments have transformed our food systems and their ability to deliver healthy diets(Reference Popkin, Corvalan and Grummer-Strawn4). Thus, dietary patterns have been shifting away from their traditional composition and moving towards diets dominated by ultra-processed foods that are high in sugar, fat and salt and low in micronutrients and fiber. Also, major technological shifts in the workplace, home, leisure and transportation have decreased physical activity levels(Reference Popkin, Adair and Ng1,Reference Popkin, Corvalan and Grummer-Strawn4) . All these changes together have contributed to increasing overweight and obesity rates.

Contrary to available evidence on the effect of unemployment on health and nutrition(Reference Kaplan, Collins and Tylavsky37–Reference Cabral, Vieira and Sawaya39), we found that the increase in unemployment rate was negatively associated with the scenarios characterised by a high burden of overweight alone and DBM. This finding is difficult to explain and may be related to the limitations of ecological data or to the unemployment rate variable, which is considered to have low sensitivity due to the high prevalence of informal work in Brazil (above 30 %) despite the reduction observed in the last decades(Reference Barbosa-Filho and Moura40).

The results further showed that the increase in the expected years of schooling was negatively associated with the nutritional scenarios characterised by stunting burden and DBM. This finding corroborates the results of other studies that identified a positive influence of maternal or paternal education level on child nutrition(Reference Monteiro, Benicio and Conde41,Reference Zhang, Huang and Yang42) . Notably, access to education enables parents, in particular mothers, to acquire knowledge on health and nutrition, which may favour the provision of a balanced diet and nutritive foods needed for healthy growth and development in children(Reference Alderman and Headey43).

The increase in household crowding rate was associated with the scenario characterised by a high prevalence of stunting. Existing evidence indicates that the prevalence of undernutrition is higher among large families experiencing food insecurity(Reference Cutts, Meyers and Black44). A study conducted with families enrolled in BFP in Alagoas(Reference Cabral, Vieira and Sawaya39), one of the poorest states in Brazil, found that the odds of food insecurity were four times higher for households with four or more people. The relationship between these two variables is clearly seen in periods of crisis, such as inflation of food prices or temporary unemployment. These conditions reduce household food availability and, consequently, the per capita food consumption in large families(Reference Thorne-Lyman, Valpiani and Sun45). In addition to its association with food insecurity, overcrowding is a well-known component of the causal network of child undernutrition by increasing the risk of infectious diseases(Reference Krawinkel46).

The prevalent burden of overweight along with the still existing burden of stunting found in the study, as well as the association between the analysed nutritional scenarios and the economic and social context of the municipalities, evidence the vulnerability of children enrolled in BFP to multiple forms of malnutrition. Given the magnitude of this problem, which currently poses an increasing challenge to global health(Reference Popkin, Adair and Ng1,Reference Popkin, Corvalan and Grummer-Strawn4) , the WHO has encouraged double-duty actions for nutrition, which include interventions, programmes and policies with potential to simultaneously reduce the risk or burden of both undernutrition (including wasting, stunting and micronutrient deficiency) and overweight or diet-related NCD(Reference Hawkes, Ruel and Salm13). Conditional cash transfer programmes, such as BFP, are potential candidates for double-duty actions. However, evidence on the effects of such programmes on outcomes related to both sides of DBM is needed to enable adequate design and orientation of actions to combat all forms of malnutrition.

One of the main limitations of the present study derives from the impossibility to extrapolate the conclusions drawn from municipality-level aggregate data to the population at the individual level, inference problem known as ecological fallacy. However, the ecological design provided an effective approach to address the study aim. The use of aggregate units of analysis, such as municipalities, enabled us to investigate nutritional scenarios, including DBM at population level, and explore contextual variables associated with them. Another possible limitation is the quality and reliability of secondary data. In this regard, data were obtained from government sources, such as health information systems and demographic censuses, which are known to have high-quality standards. Possible bias resulting from interpolation for some independent variables was minimised through variable categorisation, thus reducing fluctuations artificially caused by the method. Only municipalities with available data and with at least thirty children assessed for nutritional status in each year were considered, optimising the data quality and internal validity of the study. Despite these strict criteria, 4443 municipalities were included in the study, i.e. 80 % of the total number. When compared with the characteristics of the 5507 municipalities with available data (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 2), which correspond to 98·9 % of all existing municipalities, we observed that the municipalities included in the study (Table 1) were generally similar to the entire set of 5507 municipalities. However, the loss of 1773 municipalities in the fixed effects models due to time-invariant data may represent a limitation for the external validity of the results from the regression models. Comparing the characteristics of the two subsets of municipalities, which remained in (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 3) and were dropped from the regression models (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 4), we observed that both subsets have in general similar characteristics, except for the percentage of urban population which was higher for the municipalities dropped from the models. Thus, interpretation and generalisation of these results must be made with some caution. Despite that, panel data analysis represents the main strength of the present study, as it increased the causal inference power of the evidence found, compared with traditional analysis of cross-sectional data.

In conclusion, the results indicate a decreasing trend in the prevalence of stunting and an increasing trend in the prevalence of overweight among children enrolled in the Bolsa Família conditional cash transfer. The predominant nutritional scenarios in most municipalities were characterised by high rates of overweight and by DBM, both associated with an increase in GDP per capita. The expected years of schooling, unemployment rate and household crowding were also associated with the scenarios analysed in the study.

Our findings point to an advanced and critical stage of nutrition transition among the most socio-economically vulnerable strata of the Brazilian population. This situation demands formulating and/or readjusting policies and programmes with the potential to simultaneously reduces the risk and burden of overweight and obesity as well as undernutrition. We hope that these results guide public policy makers in fully achieving the country’s commitment to the United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition and the Sustainable Development Goal 2, to reduce all forms of malnutrition among children under 5 years old by 2025.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Dr. Djanilson Barbosa dos Santos (Federal University of Recôncavo da Bahia) and CIDACS/Fiocruz researchers for comments and critical advice on the manuscript. Financial support: This work was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Brazil (grant number 001). CAPES had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: The authors’ contributions were as follows: N.J.S., R.C.R.S. and M.L.B. designed the study; N.J.S. and F.J.O.A. collected data and constructed the database; N.J.S., R.C.R.S., D.R. and R.L.F. outlined the analytical strategy; N.J.S. performed the statistical analyses, interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript; R.C.R.S., D.R., T.C. and M.L.B. interpreted the results and critically reviewed the manuscript and all authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. As the study exclusively used aggregate secondary data available in the public domain, ethics approval by a research ethics committee and informed consent are waived per Resolution n. 466/2012 of the National Commission of Ethics in Research of the National Health Council of Brazil.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020004735