Introduction

International Organisations (IOs) reflect global power configurations and inequalities.Footnote 1 This is evident in the selection of executive and other high-ranking positions in IOs, which typically allows powerful states to shape decision-making processes and norms on global governance.Footnote 2 In the UN bureaucracy, for instance, states from the Global North are overrepresented.Footnote 3 In particular, Western powers such as the United States and France maintain their hold on influential senior posts in UN peacekeeping to define the policy's guiding principles.Footnote 4 Yet, states that are excluded from the development of norms at the macro level may still be able to contest norms at the level of implementation.Footnote 5 We suggest that UN peacekeeping offers a particularly fruitful opportunity to assess whether and how less powerful states can exercise influence on key policies of IOs.

Over the past two decades, UN peacekeeping has become increasingly coercive as reflected in the shift to ‘stabilization missions’.Footnote 6 Since 1999, not a single multidimensional UN peace operation has been created based on Chapter VI of the UN Charter on the Pacific Settlement of Disputes. Mandates are now customarily based on Chapter VII, which allows for the use of force.Footnote 7 This ‘robust turn’ has taken place against the backdrop of an increased division of labour: the Global North counts with a strong representation at the UN Security Council and carries the largest share of the financial burden of peacekeeping; countries from the Global South have put the majority of boots on the ground since the 1990s while not having been able to decisively shape the ‘robust turn’.Footnote 8 As peacekeeping's ‘reliance on voluntary troop contributions … enables major providers of uniformed personnel to demand recognition in the form of leadership posts’Footnote 9 at the operational level, peace operations appear to provide a suitable area for the Global South to challenge international power configurations through the implementation and contestation of norms on whose development they had little influence.

Leadership positions in peace operations promise to be particularly significant since the UN's often contradictory mandates and conflicting demands create tensions and unclear instructions, allowing individuals ‘to exercise a great deal of discretion and autonomy to translate them into action on the ground’.Footnote 10 Compared to most executive positions in IOs, this broadens individual leaders’ room for manoeuvre despite the UN's effort to provide political, doctrinal, and conceptual guidance. Repeated appointments of nationals in the same mission can arguably even lead to ‘mission capture’,Footnote 11 in which leading personnel's countries of origin are able to exercise unprecedented influence over peacekeeping practices.

While recognising that the Global South is a heterogeneous group of states, this article departs from the premise that legacies of colonialism influence national decisions on the norms and practices of military intervention and the use of force. As such, the ‘robust turn’ in UN peacekeeping challenges the traditional foreign policy preferences against legitimising the use of force in international politics of many countries in the Global South, with the partial exception of sub-Saharan Africa.Footnote 12 By analysing the provision of leadership personnel to UN peace operations, in particular military force commanders, this article offers new insights into the extent to which states from the Global South can exercise power in IOs and contest norms created by more powerful states. Specifically, the article seeks to provide answers to the following questions: To what extent can coveted leadership positions in international settings help states from the Global South to influence norms at the implementation level? Do representatives of states from the Global South implement or contest dominant international norms according to their respective country's policy preferences, or do they diverge from their home country's stance?

The focus on mission leadership personnel allows to analyse both their contribution to the implementation of coercive peacekeeping norms and their relationship to the stated foreign policy goals of their respective home country. More broadly, this focus on the contestation of norms through individuals’ behaviour on the ground provides insights into whether states from the Global South can circumvent existing power balances in international politics.Footnote 13 The article thus contributes to constructivist approaches that focus on the contested institutionalisation and implementation of norms,Footnote 14 different perspectives on agency-problems in IOs,Footnote 15 as well as issues of inequality and power distribution in global governance.Footnote 16 In focusing on the role of individuals, we provide new perspectives to the literature on norm contestation, which remains predominantly interested in global governance and focused on the analytical level of states, IOs, NGOs, and civil society organisations.Footnote 17 As norms research is particularly interested in the consequences of norm contestation for the meaning and further use of the norm itself,Footnote 18 we provide additional analytical tools for examining how potentially consequential contestation takes place. In line with critics who suggest that most academic studies on norm contestation remain focused on improving the legitimacy of global order through discursive practices while discounting a more radical ‘contestation as a manifestation of counter-power’,Footnote 19 we analyse different ways in which power by states from the Global South and their representatives manifests itself.

The remainder is divided into four parts. First, we clarify our conceptual approach, discuss the contested institutionalisation and implementation of ‘robust’ peacekeeping norms, and highlight the significance of military force commanders (FCs) therein. Using an original dataset on peacekeeping leadership personnel, we suggest the Global South has been well positioned to influence peacekeeping practice, especially through the position of FCs who lead the missions’ military component. In a second step, we develop a novel conceptualisation of individual norm implementers, which provides a useful tool also for analysing the agency of individuals in relation to the power of states in implementing norms across different policy areas and IOs. In the third part, we then use qualitative case studies to take a closer look at the practices of individual representatives of the Global South. Analyses of FCs from three countries that together are representative of the variety of Global Southern perspectives on peacekeeping norms regarding force – Brazil, India, and Rwanda – allow us to assess the degree to which power relationships in UN peacekeeping constrained these FCs’ room for manoeuvre. Based on an analysis of documents from the UN's different bodies and agencies, international organisations and NGOs, secondary literature, as well as interviews with two of the FCs studied and three persons with privileged knowledge on some of the FCs included in the analysis, our findings indicate that leadership appointments only allow limited influence for states who aim to contest norms at the implementation level. Individual agency clearly matters in multinational, complex environments such as UN peacekeeping, but this influence is significantly constrained by power dynamics within the organisation: the more their respective country of origin opposes robust norms, the less likely it is that individual FCs come to contest these norms. Moreover, the study suggests that civil-military relations can explain force commanders’ alignment with the political preferences of their respective governments: it appears more likely that military officers pursue institutional goals when there is significant military autonomy. We further find that great powers and relevant UN bureaucracies might be able to exploit the political ambitions of troop contributing countries. Leadership appointments are deemed as recognition and help the UN to signal commitment to Global South states’ objections regarding their exclusion from decision-making processes on the development of peacekeeping norms. However, by exercising pressure on FCs or by strategically selecting individuals willing to implement robust norms, the UN and the UNSC ensure that the mandate is implemented as intended. For troop contributors who are broadly in line with robust peacekeeping norms, however, leadership positions provide ample opportunity to advance their respective interpretation of mandates. Lastly, in a fourth step, the concluding section summarises the argument and discusses its implications for the study of norms, practices, and IOs.

The making of peacekeeping: The ‘robust turn’, norm contestation, and the importance of force commanders

Peacekeeping underwent profound changes in the past two decades. Following the recommendation of the UN Brahimi Panel Report, mandates now specify ‘an operation's authority to use force’ in order ‘to pose a credible deterrent threat, in contrast to the symbolic and non-threatening presence that characterizes traditional peacekeeping’.Footnote 20 These coercive measures are widely advocated to protect civilians, ensure the safe delivery of humanitarian aid, and bolster state authority.Footnote 21 At the same time, many countries from North America and Western Europe gradually but steadily abandoned UN peacekeeping, while the Global South stepped up its commitment. In 2020, over two-thirds of the UN's peacekeeping budget was paid for by six countries: the US (27.89 per cent), China (15.21 per cent), Japan (8.56 per cent), Germany (6.09 per cent), the UK (5.79 per cent) and France (5.61 per cent).Footnote 22 These contributions translate into decision-making power when it comes to missions and resource allocation. The US, the UK, and France hold a permanent seat at the Security Council and serve as ‘penholders’ with the largest leeway in drafting mandates.Footnote 23 This contrasts with the provision of troops: as of July 2021, the first 16 ranks on the list of top contributors were held by countries from the Global South.Footnote 24

At first sight, this division of labour would suggest that ‘Northern’ states maintain their influence on designing missions while ‘Southern’ states would act as mere ‘norm followers’.Footnote 25 However, the North-South divide is simplistic and easily risks obfuscating important differences on both sides. As we will elaborate further in the case studies below, some African states such as Rwanda are proponents of coercive peacekeeping and the turn to stabilisation. Most countries of the Global South, however, have been sceptical towards the growing use of force.Footnote 26 Thus, when the Brahimi Panel Report highlighted the necessity of robust peacekeeping, its approach was contested by many important troop contributors.Footnote 27 A former Indian ambassador to the UN summarised the view of reluctant states from the Global South as follows: ‘if peacekeeping is to be seen as peace enforcement, then unfortunately we can't see the UN charter allowing such a radical departure.’Footnote 28 Apart from scepticism on political grounds, there have also been ongoing accusations of ‘risk aversion’Footnote 29 among contingents from the Global South that stood by when civilian populations were attacked or other mission objectives severely thwarted.Footnote 30 Based on these considerations, it is clear that allegations that Southern states merely provide soldiers for implementing the agendas of great powers are overly simplistic.

In order to provide a more accurate analysis of the influence of states from the Global South on peacekeeping, this article examines the conditions under which representatives of troop contributors implement or contest peacekeeping norms. We build on Antje Wiener's understanding of norm contestation as ‘social practices’ that ‘express disapproval of norms’,Footnote 31 but broaden the analytical scope by taking concrete actions into account. This will provide a better understanding of the power of individuals in the contestation of norms and – as we will explain in detail in the next chapter – the conditions under which individual state representatives depart from their respective government's position towards a given norm. Contestation is ideal-typically distinguished as either addressing ‘the validity or the application dimension of norms’.Footnote 32 We understand contestation of the validity of norms as discursive interventions of states in the development of norms, which in this article is empirically being assessed through statements of state officials and other documents stating foreign policy preferences. The empirical focus on contestation in the application dimension lies on the behaviour of individual force commanders, whose actions are being compared to the discursive interventions of their respective governments.

In the case of norms on the use of force in UN peacekeeping, the discursive intervention of states from the Global South has precipitated ample possibilities for contestation at the level of application: while the development of robust peacekeeping norms has been led by the great powers in the UNSC,Footnote 33 objections largely from the Global South have contributed to ambiguities in the institutionalisation of norms, as a consensus-seeking UN Secretariat omitted controversial issues from official documents.Footnote 34 Consequently, peacekeeping mandates are often deliberately vague, allowing for different interpretations by those implementing them. For states that failed or only partially succeeded in contesting the validity of peacekeeping norms, the application dimension offers opportunities to exercise agency by shaping a norm's interpretation.

As an unwritten rule at the UN, troop contributions boost the candidacies of a country to assume mission leadership positions, which have allowed for ‘the practical contribution to norm making by [contributing countries] outside the West’.Footnote 35 Among the different peacekeeping leadership positions tasked with the implementation of robust norms, the Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG) and the force commander stand out as the ones with the greatest influence.Footnote 36 Since the coercive turn has raised the importance of military leaders, we focus on FCs as the crucial link for putting robust peacekeeping norms into practice. Sitting at the top of the mission's military hierarchy, FCs decide how to interpret the often vaguely defined mandates and rules of engagement and thereby set the level of force to be used beyond peacekeeping's traditional focus on self-defence.Footnote 37 However, the leeway of FCs is not unlimited and neither is their allegiance to either the UN or their home country clear. First, the selection process matters when considering whether an appointment can serve to contest norms. As previously stated, the selection of leadership personnel is highly politicised. Countries from the Global South are typically being rewarded with leadership posts if they have previously made a substantial commitment to the provision of troops.Footnote 38 Typically, the Military Advisor's Office of the UN Department of UN Peace Operations sends a verbal communication to member states informing about the possible vacancy of FC posts.Footnote 39 If a state is invited and agrees to provide a force commander, the UN Secretariat asks for a shortlist of suitable candidates, out of which the UN picks a candidate after an interview process in New York.Footnote 40 While this allows troop contributors to pre-select candidates, our case study of Brazil shows that not all FCs are selected according to the established procedure, thus providing the UN with greater leverage to appoint individuals who may end up undermining their home state's preferences.

Second, once appointed, research has shown that underperformance of missions is associated with shorter tenures for FCs, meaning that the UN Secretariat seeks to replace military leaders who fail to achieve major goals of the mission, for instance a reduction of violence against civilians. FCs from influential countries are less likely to be replaced than those from smaller troop contributors,Footnote 41 which reveals important power hierarchies that complicate the potential relation between leadership positions and a country's influence on shaping international norms.

Third, the position of FC comes with a peculiar relationship within the UN. On the one hand, because FCs are appointed by the Secretary General, the logic of their role is similar to those of other civil servants employed by the UN whose agency might contradict the preferences of their country of origin.Footnote 42 On the other hand, FCs rarely have a background of being seconded to the UN for extended periods of time. Therefore, they are not subject to the socialisation processes that are usually supposed to lead to autonomy from their home countries among long-time civil servants.Footnote 43

Fourth, FCs’ power to set the level for the use of force may be limited by ineffective command and control arrangements. UN reports show that the influence of some FCs has been fragmented due to national caveats and ‘a de facto dual line of command exercised by troop contributing countries over their troops [… to regulate] the use of force.’Footnote 44 Together, these different factors call for an empirical investigation into how norms are implemented and contested at the application level.

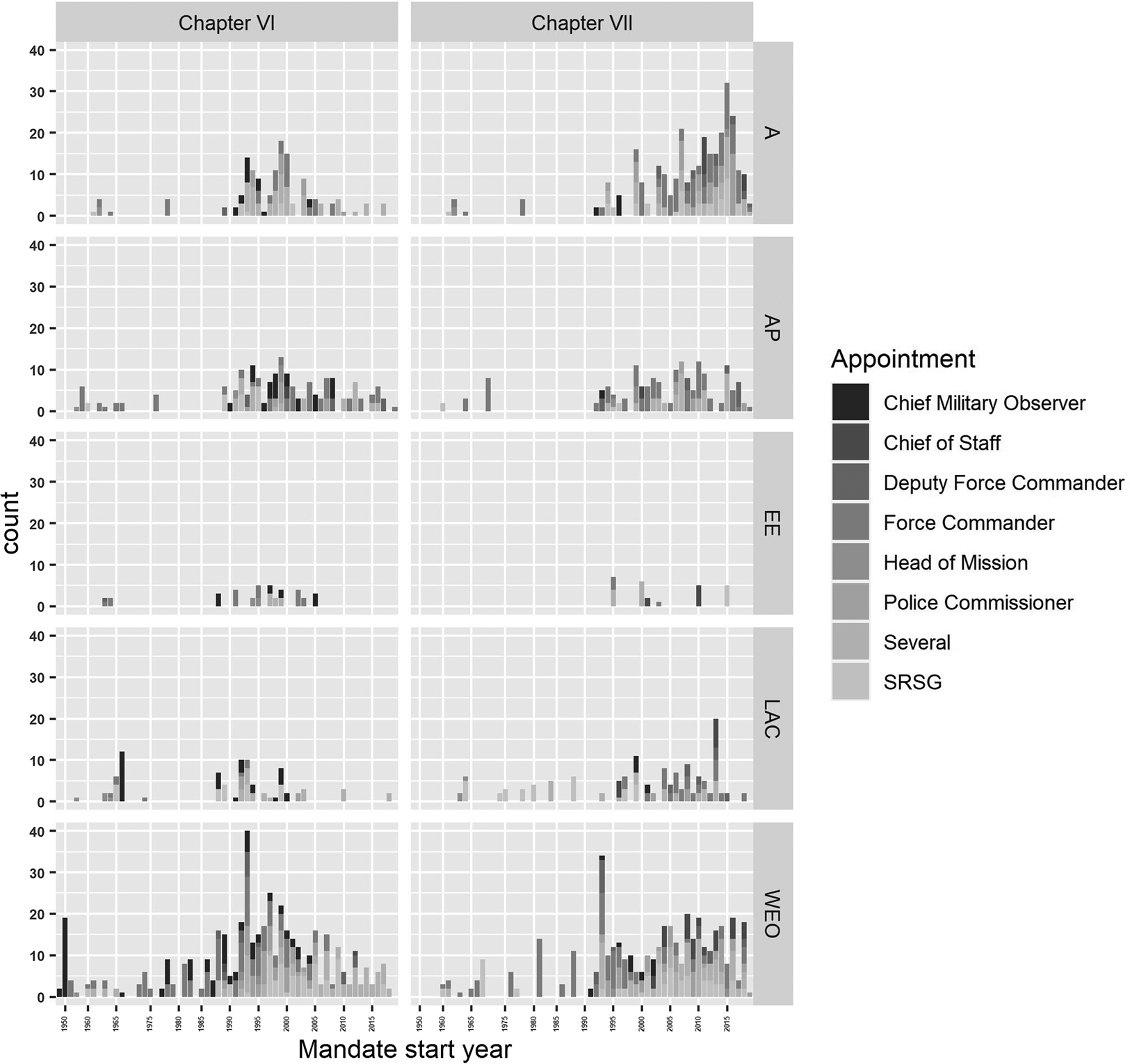

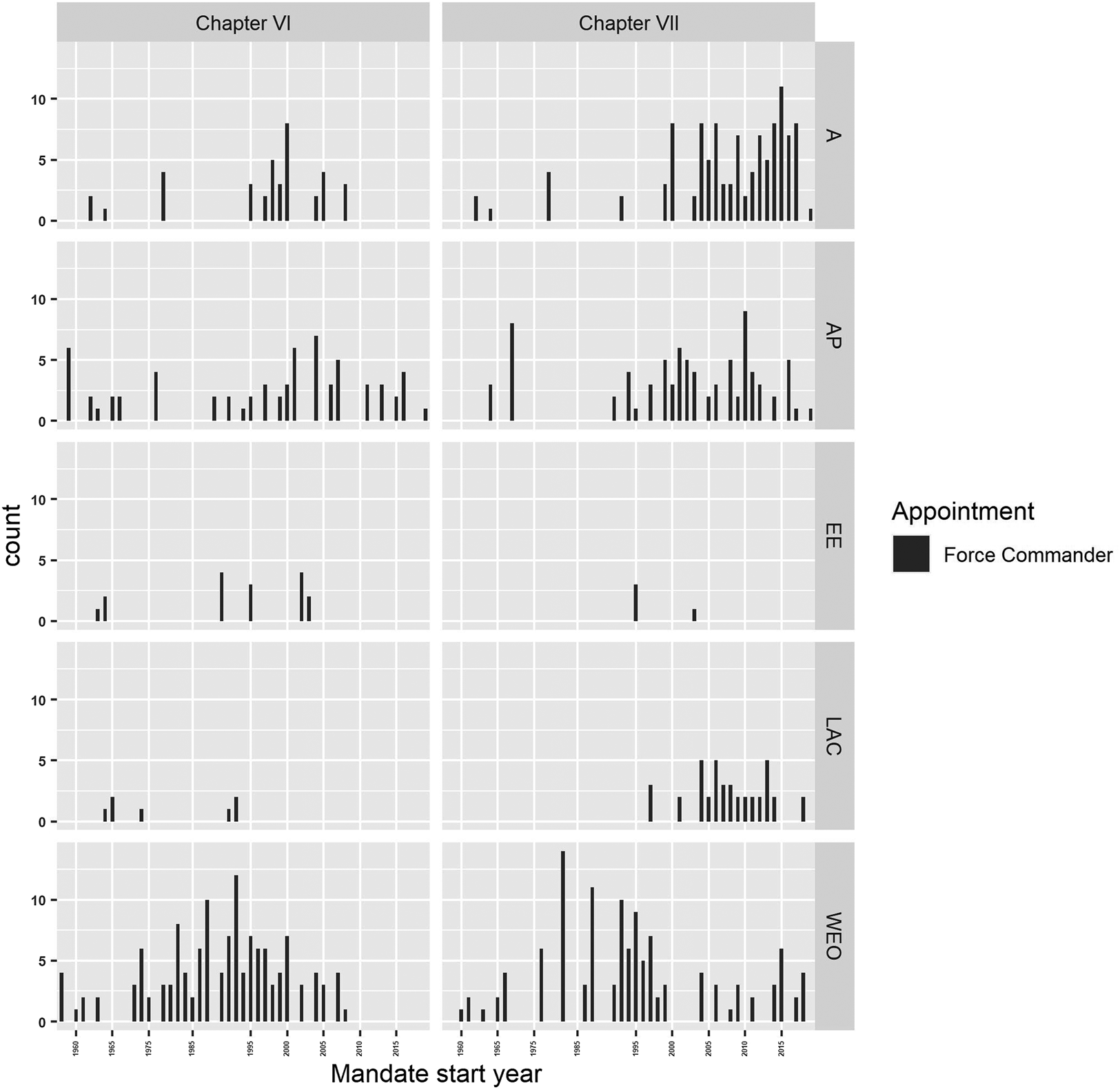

As a first step in gauging the extent to which the Global South has been in a position to shape international norms through contestation on the ground, we use a new dataset with information on leadership positions in UN peacekeeping.Footnote 45 The dataset, which is the most comprehensive one to date, contains information on seven different leadership positions in seventy UN missions that were deployed between 1948 and 2019: Head of Mission, SRSG, the different positions commanding the security forces, namely: Force Commander, Deputy Force Commander, Police Commissioner and Chief Military Observer, and mission Chief of Staff. As shown in Figure 1, over the past 25 years African and, to a lesser extent, Asian and Latin American states have attained a significant number of leadership positions in Chapter VII missions.Footnote 46 Interestingly though, despite the nearly complete withdrawal of troop contributions from the Global North, the group comprising Western Europe and the US still represents the second largest group with leadership positions in Chapter VII missions. It also holds the largest number of leadership positions in Chapter VI missions. The fact that the same states that dominate the institutionalisation of robust peacekeeping norms maintain a sizeable presence in mission leadership despite providing considerably fewer troops indicates their interest in overseeing implementation. Nevertheless, a closer look at the appointments of FCs in Chapter VII missions reveals that these have increasingly come from the Global South (see Figure 2), thus opening a window of opportunity for these states to influence how and when force is being used.

Figure 1. Individual leadership appointments divided by type of mission and personnel's region of origin.

Figure 2. Force commanders divided by type of mission.

For a better understanding of individuals’ behaviour in the contestation of peacekeeping norms, the following section develops a conceptual framework for the role of implementers in leadership positions. Beyond peacekeeping, the framework is applicable to other areas of contested international norms and practices in IOs.

Conceptualising the role of implementers

An agency-centred approach focusing on practical norm implementation and contestation rejects the idea that power is something fixed that ‘belongs’ to a certain actor.Footnote 47 Thus, it allows us to move beyond the state-based debate on whether countries from the Global South are merely norm takers who execute policies that were defined by, and represent the interests of, great powers,Footnote 48 or whether they effectively yield influence in global governance.Footnote 49 In assessing the behaviour of individual leaders, we aim to understand to which extent their actions are being determined by UN mandates and norms, on the one hand, and by political preferences of their home countries, on the other hand.

The role of individual norm implementers is firmly embedded within macro-level structural aspects of international politics. In the context of this article's focus on FCs, this means that possible courses of action are prescribed by the respective mandate put in place by the UNSC. Despite the apparently clear directive as given by the mandate, however, the Security Council's interest in controlling the implementation of mandates varies strongly,Footnote 50 thus granting FCs different degrees of autonomy in conducting operations. This, in turn, highlights the interrelationship between political conditions and individual behaviour, especially with regards to the unintended consequences of micro-level actions that affect macro-level conditions.Footnote 51

In this article, we connect the two levels by placing particular emphasis on individual FCs’ actions and their consistency with their respective home country's foreign policy preferences. The following framework distinguishes three types of individual behaviour that shape the development of international norms through practice: determined norm implementation, reluctant norm implementation, and non-implementation. Depending on the foreign policy preferences of different states, we would expect FCs to behave differently when facing security challenges that merit considering the use of force.

Implementing norms: The concept's three levels

The fuzzy nature of norms – in this article, the core principles of peacekeeping and the use of force – requires a conceptual framework that captures the implementation of norms along a continuous dimension. Based on Gary Goertz's three-level approach to concept building,Footnote 52 we distinguish between basic, secondary, and indicator levels. At the basic level, the following elements need to be specified: the negative pole, the substantive content of the continuum between the negative and the positive pole, and whether continuity exists between the poles.Footnote 53 Focusing on the implementation of norms by individual leaders, the negative pole is non-implementation. Contrary to Goertz's understanding that the negative pole would usually entail ‘no independent theoretical existence’,Footnote 54 the negative pole in our conceptualisation does have clear ramifications. Not implementing norms can be understood as open contestation,Footnote 55 although it does not necessarily mean that norms are purposefully contested: actors might simply interpret norms differently and act accordingly.Footnote 56 Abstaining from using force in situations when others asked them to do so shall suffice to be classified at the non-implementing end of the continuum. Consequently, the positive pole is full implementation. Since the implementation of norms is hardly a dichotomous choice in practice, it is our understanding that individuals can ‘move along the continuum to points in between them’Footnote 57 and change their behaviour over time.

At the secondary level, the substantive content of the continuum translates into varying degrees of implementation and non-implementation. Within the category of implementers, we distinguish two degrees of behaviour: determination and reluctance. Determined implementers implement a given IO's norms under any circumstances even against resistance, be it from stakeholders in their country of origin or else. Reluctant enforcers, on the other hand, implement norms according to the preferences of the IO Secretariat or its dominant states, but do so against their personal preferences and/or their respective country's official policy position. Reluctance can be identified through recalcitrance and hesitation,Footnote 58 which can be observed in declarations and actions. Lastly, to operationalise the concept's third level, hesitation will be evidenced if there is a lack of initiative, delaying, and flip-flopping.Footnote 59 Indicators for recalcitrance are ignoring or rejecting requests, as well as obstructing others’ initiatives.

To probe the conceptualisation's usefulness and illustrate its application, we analyse the implementation of robust mandates by selected FCs from Brazil, India, and Rwanda. For each case, we assess whether and to what extent FCs have contested norms on the use of force, and whether this aligned with their country of origin's expected policy preferences. The countries were selected based on the criteria that they were significant troop contributors during the term in office of the FCs studied and that they belong to different UN Regional Groups of Member States representing the Global South (Latin American and Caribbean Group, Asia-Pacific, and Africa). Moreover, similar to John Gerring's diverse case method,Footnote 60 the selection achieves variance along the dimension of interest. Following this logic, each country typifies a different position on the use of force. As the case studies will further elaborate, based on their respective policy positions during the development of peacekeeping norms at the macro level, at the micro level we expect Brazilian and Indian FCs to act as reluctant implementers, and Rwandan FCs as determined implementers. This purposive sample aims to demonstrate variety of perspectives from the Global South on the normative development regarding the use of force.

Since the perspectives are heterogeneous within each regional grouping, it is important to note that the selected countries cannot be understood as representative of their region but rather of diverse positions that can be found across the Global South. Part of this diversity is the plurality of civil-military relations models, which define the degree of autonomy FCs will have from their home countries’ foreign policy establishments, thus influencing states’ ability to contest international norms via leadership appointments. For the cases of Brazil and Indonesia, for instance, it has been shown that military autonomy in peacekeeping matters has allowed the armed forces to adopt a more robust posture than most national policymakers and diplomats were willing to endorse.Footnote 61 The three cases of this study range from firmly institutionalised civilian supremacy over an apolitical military in India to patchy civilian supremacy in Brazil and to a politicised and politically powerful military in Rwanda,Footnote 62 thus adding analytical richness to the study. After all, FCs have strong incentives to avoid bad international press for their home country regardless of the specific civil-military relations equilibrium prevailing in the national context.

The individual FCs analysed in the case studies below were chosen in two steps. From all FCs from a given country we selected those who had been deployed between 2000 and 2019 in a mission with a real possibility that force would be considered necessary and requested by relevant actors, for instance members of the Security Council or the Department of Peace Operations.Footnote 63 From this pool we selected at least one FC for each country based on the practical consideration that information on their term in office and their views on the use of force was publicly available. The resulting selection does not claim to be representative for the respective countries although we are not aware of any systematic bias that may have resulted from the two-step process. Rather than deriving generalisable conclusions for each country, the main purpose here is to reveal the different factors at work in defining when and how the implementation of peacekeeping on the ground by leaders from the Global South shapes dominant norms.

Qualitative evidence: Norm implementers from the Global South

Brazil

At least since the beginning of the twentieth century, Brazil's foreign policy aimed to achieve greater status and influence in global politics, while avoiding the use of hard power and military force.Footnote 64 Between the early 1990s and approximately 2010, Brazil was one of the ‘emerging powers’ that were expected to shape global politics in the future. In this period, its foreign policy community was guided by the ‘overly optimistic view’Footnote 65 that the country would be able to achieve a permanent seat in the UN Security Council. It is against this background that Brazil's participation in the UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH, 2004–17) was both an opportunity to prove its reliability in the provision of regional order and a challenge to traditional foreign policy preferences.

The principles of non-intervention and peaceful conflict-solution are enshrined in Brazil's Constitution. The country has traditionally been highly sceptical regarding the use of force in peacekeeping and has tried to exercise influence by proposing alternatives to intervention norms developed by Western states.Footnote 66 Even during the genocide in Rwanda, Brazil insisted that the international response should be based on Chapter VI of the UN Charter.Footnote 67 Being asked to take over a leading role in MINUSTAH, the UN's first explicit ‘stabilisation’ operation, therefore required a balancing act for Brazil's foreign policy community. They saw peacekeeping as a desirable field for foreign policy engagement, which forced Brazil to marry its traditional principle of non-intervention to the concept of ‘non-indifference’.Footnote 68 In return for Brazil's prominent role in MINUSTAH, its diplomats succeeded in reformulating the mission's mandate so that Chapter VII was only invoked in specific sections. Thus, Brazil was able to claim that it was mainly concerned with the socioeconomic aspects of MINUSTAH.Footnote 69

Judging by the country's diplomatic stance, we would expect Brazilian force commanders to act as reluctant norm implementers. Notably, out of 15 Brazilian FCs, 12 were deployed in Chapter VII operations.Footnote 70 We apply our conceptualisation to the trajectory of two Brazilian army officers, who served as force commanders during MINUSTAH's most conflict-intense phase: General Augusto Heleno (2004–05) and General Carlos Alberto dos Santos Cruz (2007–09), as well as the latter's later tenure as FC of the Stabilisation Mission in the DR Congo (MONUSCO, 2013–15).

General Heleno volunteered to become the first Brazilian FC in MINUSTAH and, in an unusual nomination process, was the only officer the military proposed to the Ministry of Defence.Footnote 71 He oversaw a troop contingent that mainly consisted of Latin American peacekeepers without significant experience in war or Chapter VII missions. Summarising his one-year long tenure as FC, we classify Heleno as an initial non-implementer representing his country's official foreign policy stance who, at the behest of great powers and the UN, moved along the continuum and became a reluctant norm enforcer. Initially, Heleno withstood pressure from Haitian government officials, UN bureaucrats, and representatives of penholder countries to use the mandate's leeway against armed groups and instead insisted on the official Brazilian emphasis on socioeconomic development.Footnote 72 His focus on non-violent conflict resolution and reluctance to use force against criminals led some in the mission to compare him to a ‘development economist or a philosopher rather than a soldier’.Footnote 73 The UN's Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCCHA) stated at the time: ‘If the Government of Brazil is unable or unwilling to allow its military to stop spoilers, another nation should be designated to lead MINUSTAH.’Footnote 74 The United States even threatened to deploy their own troops if the Brazilian commander did not succeed in reducing the threat posed by armed groups.Footnote 75

Heleno contested peacekeeping norms at the micro level as he clearly behaved according to the indicators for hesitation and recalcitrance: he showed a lack of initiative regarding the implementation of the robust mandate and repeatedly rejected requests for using force. Yet, under increasing pressure from great powers and the UN Secretariat, to the displeasure of the Brazilian government and the majority of its diplomats, Heleno eventually departed from Brazil's foreign policy principles and ordered violent incursions into territory controlled by non-state actors. To do so, he, as well as his successors, relied mainly on Brazilian troops as many other contributing militaries were either unwilling or unable to carry out intervention operations. During the most infamous operation under Heleno's command, UN peacekeepers fired over 22,000 rounds of ammunition in a densely populated neighbourhood, which killed several bystanders.Footnote 76

By contrast, General Santos Cruz can be classified as a determined norm enforcer. The General was chosen after the previous force commander's unexpected death and his selection followed an unusual procedure: ‘there was little time to decide. Santos Cruz emerged as a good pick because the army thought he would bring the technical competence and would not have psychological problems with the situation in Haiti’, a Brazilian public servant explained.Footnote 77 Santos Cruz embraced the room for manoeuvre of MINUSTAH's mandate from the beginning. Under his command, MINUSTAH managed to ‘pacify’ areas of Port-au-Prince that had been controlled by armed groups. The robust action was welcomed among the penholder states that had pressured his predecessors to use force more decidedly. The US Permanent Representative to the UN, for instance, highlighted the pacification of the Cité Soleil-neighbourhood as a great success.Footnote 78 Rewarding Santos Cruz's leading role in the stabilisation, the UN later invited him to become FC of MONUSCO. The mission in the Congo epitomises peacekeeping's robust turn towards peace enforcement by giving its Force Intervention Brigade the unprecedented mandate for offensive operations against rebel groups.Footnote 79 The fact that Santos Cruz had already retired from active-duty military service when asked to lead the highly coercive mission posed difficulties for Brazil's diplomacy and its ‘historical attachment to non-intervention policies’.Footnote 80 The country had previously denied requests to send troops to the Congo on the grounds that the use of force contradicted peacekeeping's fundamental principles. This position, which had remained largely unchanged despite the experience in MINUSTAH, likely explains why Santos Cruz received the UN's invitation directly via phone by the UN Secretary General's Military Advisor, Babacar Gaye,Footnote 81 himself a former FC in the Congo, rather than through the Brazilian diplomatic mission in New York. Only after some diplomatic hiccups, Santos Cruz returned to active-duty service in order to be able to serve as MONUSCO's FC from May 2013 to December 2015. Aspiring to play a role in global politics, Brazilian policymakers and diplomats found themselves unable to turn down the UN's request despite their unease about the country's involvement in robust missions. This also underlines how the considerable autonomy of the military in Brazil can affect peacekeeping contributions: it is highly unlikely that a personal invitation to a general would have been accepted by countries with firmer civilian control over their military.

Santos Cruz's professional trajectory highlights how practices of FCs can contradict the official policy preferences of their country of origin and force diplomats into uncomfortable positions. He is a clear example of becoming member of a transnational community of practice with their own understandings and interpretation of norms, which incentivise and reward certain behaviour.Footnote 82 Importantly, Edmond Mulet, then SRSG in Haiti, fully backed his actions. Mulet, a diplomat, even adopted the military language of ‘collateral damage’ when regretting that robust operations had caused civilian deaths.Footnote 83 He later became Assistant Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations and praised stabilisation efforts in Haiti when lobbying for Brazilian troop contributions.Footnote 84 To this transnational community, Santos Cruz appeared to be the ideal choice for heading the mission in the Congo. There, Santos Cruz once again proved to be a determined norm enforcer, as he saw the proactive use of force as crucial for protecting civilians. To prevent that national caveats to an aggressive posture would undermine his command, the General sought to maintain contact to the different contingents at all times making sure that his orders would be implemented as intended. ‘I knew they received advice from their capital. This kind of influence is very strong because it is very present, there is Whatsapping every day. But when you talk, then you can work around it. The culture in the military is the same everywhere: I won't say no to a dangerous situation, that is a question of honor. This is what helps to convince them [to use force].’Footnote 85

The UN chose to pair Santos Cruz with a SRSG from Germany, a country, like Brazil, known for its reluctance to use force in international politics.Footnote 86 However, true to SRSG Martin Kobler's ‘reputation for activism’,Footnote 87 he fully endorsed the FC's readiness to rely on the military component against the rebels. Santos Cruz confirmed the importance of close and trustful relations within the mission leadership: ‘The SRSG needs to be with you in all instances … one working diplomatically and the other operationally … Fortunately, in my case I had a good relation with Edmond Mulet and also with Martin Kobler.’Footnote 88

The above shows that the choice of particular individuals allows the UN to create and foster communities of practice willing to implement norms according to the wishes of the Secretariat. After being credited for the military defeat of the M23 rebel group in the Congo, the UN asked Santos Cruz to lead the production of a report on protecting UN peacekeepers. Its result, known as the Cruz Report, caused a stir for its vocal demands for greater use of force. His emphasis on the utility of ‘overwhelming force’ made him an ‘unusually hawkish variety of UN general. His unforgiving views on when and how to use force are closer to that of a NATO officer than those of more mainstream non-Western peacekeepers.’Footnote 89 This further underlines that Cruz's self-understanding as a military officer and his belonging to a transnational community are more relevant for his operational decisions than his nationality. As Santos Cruz's career at the UN raised his country's international profile, Brazilian diplomats grudgingly accepted his role although his practices clearly contradicted long-standing foreign policy preferences. His case shows that by selecting leaders from states ambitious to raise their international profile while making sure that these implement norms at the micro level as agreed at the macro level of decision-making, established powers and IO secretariats may be able to exploit emerging powers’ desire to gain international prominence as well as their eventual lack of supremacy over the military.

Practices of both Brazilian FCs contradict the expectations derived from the country's declared foreign policy preferences. Rather than being a foreign policy tool for contesting international norms at the implementation level, the FC's actions have forced national diplomats to reluctantly adjust their positions on these norms. As their respective tenures have shown, power relations within the UN and pressure by powerful states can create an environment in which leading personnel reluctantly or determinedly departs from their country of origins’ normative stance.

India

After independence from British rule in 1947, India adopted a normative foreign policy stance prioritising non-intervention and the peaceful resolution of conflict, as stated in the Constitution. These two principles have also been institutionalised in the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), in which India's first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru played a leading role. Similar to Brazil at the beginning of the twenty-first century, India has been considered an emerging power on the world stage in recent decades. India has placed great emphasis on being engaged in multilateral institutions such as the United Nations, and has looked at peacekeeping as a potential pathway towards gaining a permanent seat at the UN Security Council.Footnote 90 Trying to balance its desire for greater influence on global politics and its normative preferences, India has tried to harness its extraordinary troop contributions for gaining leverage over the design of missions,Footnote 91 a strategy that is summarised in the idea of ‘making a difference through its participation’.Footnote 92

Still, Indian diplomats and policymakers have shown some flexibility in supporting robust approaches to peacekeeping, citing operational necessities and their country's commitment to the UN.Footnote 93 Indian officers have served as FCs on 19 occasions, out of which seven took place under a Chapter VII mandate.Footnote 94 This apparent mismatch between rhetorical opposition at the level of policy making and implementation at the micro level dates back to India's first major peacekeeping contribution to ONUC in the Congo during the 1960s, which at times resembled current ‘robust’ operationsFootnote 95 and during which India ‘clearly demonstrated its willingness to use force.’Footnote 96 Nevertheless, India has remained critical of more permissive forms of coercive peacekeeping and its potential to become instrumentalised ‘as an instrument to wage war’ for the narrow interests of the permanent members of the Security Council.Footnote 97 As the country has shown hesitance in explicitly adopting Western-led coercive peacekeeping norms, while still contributing significantly to these operations, we expect Indian FCs to reluctantly implement robust peacekeeping norms. We test this assumption with an evaluation of General Chander Prakash's command of MONUSCO (previously called MONUC).

Prakash was appointed as FC in 2010 after having been selected from a pool of eligible officers in his home country and following ‘a quite stringent selection process at the UN, with a long interview’.Footnote 98 He headed the mission for two-and-a-half years until March 2013, during which peacekeepers have been accused of failing to guarantee the protection of the civilian population against violence committed by various rebel groups in the Eastern Congo.Footnote 99 In the following, we will elaborate why we consider Prakash a reluctant implementer whose decisions have mainly been in line with his country of origin's preferences.

India had been a crucial troop and equipment provider to the missions in the Congo well before Prakash assumed command. For instance, India facilitated core elements of the mission's robust posture by providing attack and transport helicopters. Yet MONUC/MONUSCO in general, and the Indian troop contingent in particular, had regularly been accused by Western countries of being unwilling to use force to protect civilians as stated in the mandate.Footnote 100 Calls from Western states to implement forceful measures were repeatedly rebutted by Indian officers claiming that mandates were unrealistic and the mission ill equipped to effectively protect civilians.Footnote 101 Contrary to the Brazilian FCs discussed above, despite coming under pressure from the UN, Prakash implemented the mandate in line with India's policy preferences rather consistently. In the aftermath of the NATO intervention in Libya in 2011 and the ensuing discussion regarding intervention norms such as R2P, Indian diplomats leveraged their country's peacekeeping contributions to exercise influence. India withdrew its attack helicopters from MONUSCO, thus dismantling some of the mission's most crucial force projection capabilities.Footnote 102 At the same time, Prakash adopted a rather traditional, reactive posture regarding the use of force, which arguably prevented blue helmets from offering more effective protection.Footnote 103

Among the many challenges of Prakash's tenure, the takeover of Goma (the capital of North Kivu province) by the Rwanda-backed M23 rebel group stands out. Despite having been warned of the M23's offensive, blue helmets were unable to defend the city as the Congolese army they were supposed to support proved ineffective.Footnote 104 According to Prakash, he had told ‘a contingent commander to fight to push them back at all costs’, yet the commander of undisclosed nationality ‘replied that his country had sent him to keep the peace, not to make war. The challenge is that each state can interpret our mandate differently.’Footnote 105 These ‘parallel problem definitions’,Footnote 106 which have been an inherent difficulty in the UN's robust turn, made it harder for Prakash to pursue a coercive approach even if he would have favoured forceful actions. This, however, can hardly be assumed. In Prakash's view: ‘any robust action to stop the M23 would have resulted in a fair amount of collateral damage. Goma is a city with a large built-up area, densely populated.’Footnote 107 The former FC recalled that he and his Deputy patrolled the area the day the M23 entered the city:

there were no serious human right violations, markets were open and people were moving around as if nothing had happened. The peacekeepers helped to evacuate the Governor and some others who were under threat from the M23. The problem was that the mission lacked strategic communications and the media painted a bad picture because bad news sells.

Consider further that a co-authored contribution of the former FC emphasised how India was ‘especially concerned’ about the offensive Force Intervention Brigade, which was deployed as part of MONUSCO when he left office.Footnote 108 On another occasion, he affirmed that ‘the FIB contributed to the perception that MONUSCO and the UN are becoming increasingly belligerent.’Footnote 109 This echoed India's official position that peacekeepers were increasingly and unduly being asked to fight to enforce peace.Footnote 110 In a Security Council meeting on operational challenges, Prakash made it again clear that he, in line with India's diplomatic representation at the UN,Footnote 111 favoured a clear distinction between peacekeeping and the use of force beyond self-defence, when he reported that ‘contingents trained for fighting, not peacekeeping, did not seem to understand the goal.’Footnote 112 Thus, in the General's view: ‘The people who criticized MONUSCO for not being robust did not fully understand the challenges on the ground. The principle of impartiality must not be violated.’Footnote 113

Former MONUSCO personnel agree that ‘the conventional wisdom that the FC takes political direction from their capital is usually correct, and it certainly was in this case.’Footnote 114 While we are unable to provide any definitive evidence for such directions, the claim is plausible considering the overlap between India's official position and Prakash's authoritative decisions on the use of force in addition to the fact that the Indian army is an apolitical institution firmly under civilian control. India was unhappy with the growing coerciveness of the UN's involvement in the DRC. New Delhi's informal perspective ‘was that they have to get along to go along’,Footnote 115 which implied supporting the use of force reluctantly to be able to lead the mission and eventually change practices of using force on the ground. As such, coercive peacekeeping is another example of ‘India's “silent contestation” at the implementation stage’Footnote 116 of dominant interpretations of international norms on security governance.

Summing up Prakash's term, providing the FC helped India to contest the growing trend towards peace enforcement that challenges principles of traditional peacekeeping. In an apparent attempt to work around India's comparatively successful norm contestation, the UN personally invited the Brazilian General Santos Cruz to succeed Prakash and to command MONUSCO's definite turn towards peace enforcement that included combat operations against rebel groups. This is a sign that the UN and great powers might be able to circumvent comparatively influential troop contributors’ reluctance at the implementation stage by strategically selecting more ‘willing’ leadership personnel from other countries of the Global South.

Rwanda

Different to Brazil and India, Rwanda lacks significant ambitions to shape global politics in multilateral institutions. Most analysts agree that Rwandan foreign policy is deeply shaped by the fact that the world basically abandoned the country during the 1993–4 genocide – and that Rwanda has used this ‘guilt card to demand specialised treatment in terms of receiving foreign aid and deflecting current accusations concerning its domestic human rights record’.Footnote 117 However, reality is more complex and Rwanda's current foreign policy is marked by its interest to present the country as a safe destination for investment as well as a reliable recipient of foreign aid. The experience of genocide, however, remains to shape the country's position on the use of force.

Rwanda belongs to a small group of states from the Global South that has openly advocated robust peacekeeping. The country has become one of the top troop contributing countries to UN and AU (African Union) peace operations since it deployed its first peacekeepers to the AU Mission in Sudan (AMIS) in 2004. Ten years after the genocide, the ruling Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) took it as its ‘moral mandate’Footnote 118 to contribute to AMIS, which was framed as an effort to prevent genocide in Darfur. Though there are other institutional, political, and economic motivations driving Rwanda's peacekeeping contributions,Footnote 119 the 1994 genocide is key to understand why Kigali has favoured a robust posture.Footnote 120 The experience of one of peacekeeping's biggest failures has created a ‘post-genocide national identity’ – strongly linked to the ruling RPF – in which ‘casualties … are perceived as sacrifices’ that are widely accepted.Footnote 121 Rwanda has been willing to deploy to some of the UN's most dangerous missions. The country has not assumed leading roles in Chapter VI missions, but provided four FCs to Chapter VII missions.Footnote 122 As Adama Dieng, a former UN Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide said, Rwanda deploys to places where civilians are under threat because it ‘knows exactly what genocide means. That is why when I sounded the alarm in Central African Republic in November 2013, Rwanda moved and sent troops to protect the population there.’Footnote 123

Furthermore, Rwanda has been a vocal advocate for more robust multilateral responses to crises. After having repeatedly criticised the UN's failure to provide stability in the Congo, Rwanda supported the deployment of the Force Intervention Brigade in 2013. Furthermore, Rwanda was one of the originators of the Kigali Principles that sought to complement the UN's directions on the protection of civilians. Based on the above, it may be expected that Rwandan FCs are determined norm implementers in line with their country's position on robust peacekeeping. Indeed, it will be demonstrated in the following analysis of the roles the generals Patrick Nyamvumba and Jean Bosco Kazura played as FCs in UNAMID and MINUSMA, respectively, that both fall into this category. The analysis suggests, however, that loyalty has not been the only reason for implementing the norm of robust peacekeeping in a way consistent with their home country's official stance, but that prior professional experiences also influenced how they dealt with the issue of force.

Patrick Nyamvumba assumed as FC of UNAMID in September 2009, one-and-a-half years after UNAMID had taken over from AMIS to respond to the by that time highly mediatised war in Darfur. During his three-and-a-half-year turn, Nyamvumba's position consistently echoed the one taken by the UN and the Rwandan government, when he explained that ‘peacekeepers … try to resolve issues through talks and negotiations. However, should circumstances dictate that we keep the peace by use of lethal force, we are ready to do it.’Footnote 124 On another occasion, anticipating one of the Kigali Principles, Nyamvumba restated his disposition to resort to forceful means: ‘If the threat is endangering the lives of civilians or peacekeepers, nothing should stop them [the commanders] from using force.’Footnote 125 In an event organised by the United States Institute of Peace in 2016, Nyamvumba even went so far as to declare that ‘the best way to deal with violence at times is using violent means to stop violence … those countries not willing to take those extra risks should not deploy.’Footnote 126

Based on his consistent stance favouring robust peacekeeping, Nyamvumba classifies as a determined norm implementer. In an interview that appeared in a magazine published by UNAMID, he cited examples when peacekeepers under his lead had adopted a robust posture.Footnote 127 It is true that UNAMID failed repeatedly to protect civilians ‘in the sense of taking proactive measures to ensure that civilians were safe’.Footnote 128 However, the available evidence indicates that the reasons lay not with the lack of determination on part of the leadership, but above all with personnel shortages and inadequate equipment.Footnote 129 In addition, and as previously highlighted, it needs to be considered that peacekeepers from those countries reluctant to adopt a robust approach may follow the orders of their national capital, which may contradict those given by the FC. Nyamvumba hinted at such problems when he remarked: ‘robustness begins with the state of one's mind. … we have been urging peacekeepers to overcome some of [the] obstacles placed in their way, even if it requires use of force [sic].’Footnote 130

Nyamvumba's stance as a determined norm implementer can be traced back to his country's government's official position. However, this should not be seen as merely an expression of political loyalty to the government and the ruling party, as Rwanda's civil-military amalgamation suggests.Footnote 131 Instead, it should be placed into the context of his professional trajectory as a combat-experienced officer, underscoring the point that actorness is more complex than a unitary perspective on the state may suggest. On the one hand, the FC echoed the RPF's discourse that has depicted the country's unique experience of genocide while the international community stood by as mandating a shift towards a robust approach: what ‘we have seen in Rwanda, in Srebrenica, you had the presence of peacekeepers and things happened in their presence and they didn't take action. We can't afford to do that now.’Footnote 132 On the other hand, prior to his appointment by the UN, Nyamvumba's trajectory in the armed forces had provided him with combat experience both in Rwanda and during Rwanda's second intervention in the DRC in the late 1990s. A Tutsi officer, he had been part of the RPF that ended the genocide in 1994.Footnote 133 Although it is not possible to establish a link between experiencing organised political violence and determination to use force, Nyamvumba's personal background adds authority to his words when he says that ‘if we present ourselves as a weak force, we will lose a lot of peacekeepers and equipment.’Footnote 134 As an observer with extensive insider knowledge on the Rwandan military remarked with regards to ‘the acceptance of civilian deaths in a military operation, there may be a difference in opinion when it comes to the Rwandan military leaders that have combat experience and others that have not.’Footnote 135 It is hence plausible to argue that Nyamvumba speaks from experience when asserting that ‘the only thing that can save them [the peacekeepers] and bring credibility to the Mission is that they need to be robust.’Footnote 136

Similar conditions apply to General Jean Bosco Kazura, who commanded MINUSMA from mid-2013 to December 2014. Kazura had been involved in the RPF's operation to end the genocide.Footnote 137 Having served as Senior Military and Security Adviser to President Paul Kagame just prior to his appointment at the UN, he belonged to a circle of government-loyal RPF officers that could be expected to represent Rwanda's official position in favour of a robust approach. Indeed, Kazura's role in MINUSMA shows that he was a determined norm implementer. His tour of duty began when MINUSMA took over from the African-led International Support Mission in Mali (AFISMA), with a mandate based on Chapter VII as requested by the AU.Footnote 138 Although MINUSMA was not a peace enforcement mission like AFISMA, it operated alongside French forces that conducted major combat and counterterrorism operations, and it has involved peace enforcement to the extent that many have questioned whether it can adequately be described as a peacekeeping mission.Footnote 139 Still, given an increasingly volatile security situation on the ground and the fact that MINUSMA has been the target of terrorist attacks, in a Security Council meeting in 2014 Kazura pointed to the inadequacy of the mission's approach: ‘MINUSMA is in a terrorist-fighting situation without an anti-terrorist mandate or adequate training, equipment, logistics or intelligence to deal with such a situation.’Footnote 140 He further stated: ‘today is not a good time for questions; it is time for action.’ Kazura had demonstrated a similar stance favouring decisive action backed by adequate resources years earlier when he served as Deputy Commander and Chief Military Observer of the African Union Mission in Sudan (2005–6). As he recalled, AMIS lacked the capacity to step in and protect civilians from imminent attacks by armed groups: ‘I got us to go with the APCs (armored personnel carriers) from Fasher to Shangil Tobay, so we could at least show the population that we were around. When we arrived, they were very happy … but all I could think was, if we were actually attacked, I don't know what we will do.’Footnote 141

Like the Brazilian case, the trajectory of the Rwandan generals demonstrates that the implementation of norms at the micro level is only in part determined by the nationality of leaders, per se. In the case of Rwanda, the professional experience of the FCs has likewise contributed to bringing their position on the use of force in line with the one generally advocated by the P3. As Rwanda's policy preferences were in line with the penholders in the UNSC, these powerful actors had little necessity to exercise pressure on the FCs. Since the FCs also enjoyed the backing of their government, they were largely unconstrained in interpreting the mandate according to their personal background and translating them into coercive practices on the ground.

Conclusions

This article has analysed the extent to which states from the Global South can contest norms at the micro level of implementation in order to influence core functions of IOs and thus find ways to alter the global stratification of power. Using the example of the increasing use of force in UN peace operations, we evaluated how leadership appointments allow states to shape the implementation of norms and thereby their future development. Based on a conceptual framework that allows classifying individual behaviour of leading personnel vis-à-vis their respective country of origin's foreign policy preferences, we find that a deterministic understanding of appointments as proof of national influence misses crucial nuances in individual trajectories. Our case studies showed that India was able to contest the increasing use of force via the FC, who acted as a transmission belt of his country of origin's preferences. Rwandan FCs also clearly acted according to their country's preferences, though for reasons that include their personal experiences as officers, which aligned their behaviour with the UN Secretariat's priorities. However, the case of Brazil demonstrates how countries fail to contest norms through implementation as FCs embraced enforcement norms that clearly contradict their country of origin's policy preferences. Together, the case studies demonstrate that a variety of factors simultaneously influence the role leaders play in implementing international norms to the effect that they sometimes undermine their governments’ preferences.

The findings raise questions regarding the specific conditions under which individual leaders from the Global South depart from their respective country's foreign policy preferences. Variation in how leaders act on the international stage respective to their country of origin's political stance might stem from personal background and opinions, pressure from the UN and other stakeholders, conditions in the mission host country, the composition of peacekeeping forces or, within the context of the armed forces in peacekeeping, civil-military relations.Footnote 142 For example, members of the military tend to have perspectives on the utility of force that differ from those of the foreign policy elite. Conversely, FCs might be more aware of the shortcomings of their troops and the impossibility of fulfilling a mandate than the UN Secretariat. These differences might create frictions between military leaders and their home countries’ foreign and security establishments that affect to what extent the former will stick to domestic policy lines. Moreover, great powers’ interest in closely monitoring the implementation of mandates may vary according to their relationship to the respective host country.Footnote 143 Future research on peace operations should investigate more closely these different influencing factors when trying to determine the influence of leadership positions.

On a more general level, this article adds new perspectives to the literature on power relationships in IOs, the contestation of norms, as well as on issues of inequality and power in global governance, which has mostly treated the state as a black box. Our conceptual framework of individuals’ roles in norm implementation might be a suitable tool for classifying the behaviour of staff in IOs and for comparing this to their respective country of origin's policy preferences. Our findings underline that representation at the level of norm implementation does not necessarily guarantee significant influence for states that are not powerful enough to shape decision-making processes. Established powers might find ways to strategically select individuals from the Global South who are committed to their desired interpretation of norms. The example of the Brazilian General Santos Cruz demonstrates that the UN was able to circumvent usual nomination practices by extending a personal invitation to an officer who represented views that hardly matched those of his nation's diplomacy. This calls for further research into intra-organisational power dynamics at play in complex UN peace operations and beyond. It is particularly crucial to explore how IOs and the dominant states in its hierarchy are able to exploit transnational networks of individuals who share a similar interpretation of norms against the interests of member states. A stronger focus on intra-organisational politics will not only improve our understanding of norm implementation in UN peace operations, but within IOs in general.

Acknowledgements

We owe special thanks to several people who made important contributions to this article. Kseniya Oksamytna, Chiara Ruffa, and the participants of the Colloquium of Prof. Dr Anna Geis at Helmut Schmidt University Hamburg, especially Louise Wiuff Moe, provided valuable feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript. So did four anonymous reviewers. The following persons shared their knowledge on military leaders in peace operations with us, for which we are extremely grateful: Cedric de Coning, John Karlsrud, Ralph Mamiya, and Paul Williams. Camila Bertranou provided excellent research assistance to this project. This research was funded by the German Foundation for Peace Research (Deutsche Stiftung Friedensforschung), Grant No. PS 02/11-2018, and the National Research and Development Agency (ANID, Chile), Proyecto Fondecyt Regular (2021) No. 1210067. Open Access funding was kindly provided by Technische Universität Braunschweig.