Managerial practice historically evolved around the mediating role of particular communicative genres, such as memos, reports, forms, and proposals, as new sources of knowledge production and organizational control in corporations (Yates Reference Yates1989; Yates and Orlikowski Reference Yates and Orlikowski1992). Such genres emphasized standardization, depersonalization, and wide circulation. Out of this emerged the modern figure of the manager, who ascended to the role of the “visible hand” of the market (Chandler Reference Chandler1977). The authority of the manager was grounded in an analytical stance to producing and reading standardized documents and hard data. Based on documents, however, claims of authority by managers have always been tenuous. In contrast to owners, who can ground authority in property, and workers, who can claim authority in labor value, the authority of managers has always been linked to the ambiguous position of controlling that which they neither own nor produce (Berle and Means [1932] Reference Berle and Means2007). In this sense, the standardization, depersonalization, and circulation of documents not only played a central role in coordinating corporation and markets but in establishing the authority of managers themselves.

The ways that managers ground their authority through decontextualized genres and across documentary forms resonates with theorizations of intertextuality within linguistic anthropology in two key ways. First, intertextual connections have typically been understood to operate in relation to dialogicality (Bakhtin [1930] Reference Bakhtin, Emerson, Holquist and Holquist1981) in which one discursive event is linked to recognized authorities through processes of decontextualization and entextualization (Bauman and Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1990; Kuipers Reference Kuipers1990, Reference Kuipers2013; Briggs and Bauman Reference Briggs and Bauman1992; Silverstein and Urban Reference Silverstein and Urban1996). The relationship between dialogue and text parallels the historical trajectory of the “systematic management” movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Nelson Reference Nelson1974) in which a new class of managers emerged out of a context-based management through the standardization of forms and procedures for control across space and time. Second, intertextual authority has been shown to be subject to destabilization and must constantly be revalidated through further authorizing acts (Besnier Reference Besnier and Duranti2006). While acts of intertextuality emphasize stability through the linking to recognized norms, such authority is only as stable as its continued uptake by other participants. The authority of managers has depended on standard uses of documents in which they are seen to occupy the role of the “principal” in Goffman’s (Reference Goffman1981) sense, but they have faced a number of challenges from other claimants challenging their authority within the corporation.Footnote 1

The way that managers and those inhabiting managerial roles engage with intertextuality, however, goes beyond decontextualizing oral discourse or linking to recognized genres. It entails an orientation to the material reality of modern organizational life that is defined by an engagement with already entextualized objects. Issues such as how to display textual information on paper, how to transmit files, how to cite sources, and how to store documents remain central concerns of organizational actors. These institutional realities have different implications for how intertextuality operates in practice and, in turn, how to think about authority within the corporation. Considering texts as physical objects, or “graphic artifacts” in Hull’s (Reference Hull2003) sense, we can observe how extralinguistic dimensions figure for how intertextual relations are managed and in turn how individuals orient to these dimensions as much as linguistic ones. Aesthetic qualifications of form (neatness of a document), visual organization of information, meta-textual information, and pragmatic implicatures are inextricable dimensions of organizational texts. In an intertextual sense, ways that texts become linked together (by labeling or filing), altered in transmission (by locking or censoring), or reproduced (by copying or distributing) expand the scope for practical action as well. If ethnographic cases have tended to highlight the somewhat unilinear communicative transformations from oral discourse to texts—progressive depersonalization, decontextualization from the here and now, and use of repetitive poetic structures (Kuipers Reference Kuipers1990)—for the grounding of authority, this article attempts to look at how a wider array of textual resources allows individual to adopt different stances and styles toward management itself.

The present article takes up these issues in the context of a Korean brand consulting firm. A joint venture company founded in 2010, Limelight KoreaFootnote 2 was in the midst of attempting to establish its own authority in Seoul when I interned there in the summer of 2011. This entailed presenting itself as both a brand/marketing expert to its Korean clients and a capable local project manager to its overseas partners. In both of these activities, the CEO, team managers, and other junior employees of the company drew heavily from forms, templates, old reports, manuals, research guides, and other literature in presenting and managing their work to outsiders as well as to each other internally.

Within this context of circulating documents and competing demands from clients and partners, I identified two different styles for how to both sell the company and regulate its activities. I label these styles as “intertextual display” and “intertextual discipline.” Intertextual display involved using previously developed contents, frameworks, or entire templates from other companies in Limelight’s own work. Such activities were one way to ground the company’s authority in external sources but were done so in an ad hoc manner, minimizing or maximizing intertextual gaps depending on the value of the content, the relationship with the source, and the imagined future readers. This style came to be used often in work presented to potential or current clients. Intertextual discipline, on the other hand, involved adopting bureaucratic forms to discipline office life and work activities. Like the textual practices of the systematic management movement mentioned earlier, these kinds of activities sought to establish a depersonalized authority through a textual chain of likeness across forms. As I will show in the data, the two styles differed in the semiotic dimensions with which they made intertextual connections. In the case of intertextual display, textual-visual elements as well as other properties of the texts were manipulated to diagram the links between a source document and its desired usage. In the case of intertextual discipline, textual-visual elements and procedures for handling documents were iconically structured to create an emblem of office discipline.Footnote 3

The abovementioned issues figure centrally for an emerging semiotic anthropology of the corporation and contemporary management practice. In one sense, they touch on a tension among materially oriented forms of authority in a Weberian bureaucratic sense (ruled by paper), textual authority in a Marxist ideological sense (rule by discourse), and self-authorized authority created by textual circulation in Anderson’s (Reference Anderson1991) sense. They begin to blur the locus of where actors situate textual authority—form, meaning, or circulation—and how these elements might co-occur within the same context. In another sense, however, these issues begin to demonstrate how corporate textualities in general may be distinct from other domains brought together by circulated texts. The textuality of managerial authority is one grounded in always-already detachable, depersonalized, and distributed documents and texts. As such, the objects of managerial authority bear the potential to be easily plagiarized, misused, or leaked. Thus concerns among managers focus on the material safeguarding of texts—contracts prohibiting reuse, methods for storing and “locking” files, and procedures for proper handling. In these cases, it is not just the relationship between discourse and text (entextualization) that becomes a site of investigation, but the relationship between treatments of entextualized objects that bears consideration. It is the management of these intertextual nodes where new roles, styles, and claims for authority may emerge. Limelight Korea, a small company enacting both global and corporate identities, serves as a fruitful case study for understanding how such detached texts are both appropriated and “re-entextualized” in a site on the corporate periphery both institutionally and geographically.

This article charts the company’s endeavors at managing intertextuality in different stages: from the textual level in which they worked out relationships between themselves, partners, and clients, to the material level as they managed files in circulation. In the first section, I describe the ethnographic context in which Limelight Korea was situated and how they became a nexus of documents in a rapidly changing Korean marketing field seeking new authorities. In the second section, I discuss how employees displayed relationships to other partners through various ways of linking documents and strategies of “re-entextualization.” In contrast, in the third section I look at the ways that intertextual discipline operated, showing how employees used forms, such as time and task trackers, to regulate internal office practices. The difference between these two styles was not entirely exclusive, and in the fourth section I show examples where the styles bled across each other in practice. Finally, I describe how employees altered future trajectories of documents while also appropriating them for their own imagined future uses.

Limelight Korea and Competing Authorities

Limelight Korea was originally created as an outpost of other global authorities. In 2010, two branding companies, one American and one European, founded Limelight Korea in order to expand their clientele in the Korean market. As many Korean corporations began to invest more in strategic corporate branding and brand management in the 2000s, these corporations turned to credentialed, particularly Western, consulting agencies for advice.Footnote 4 Limelight Korea served as the Korea-facing representative of these two organizations. The main objectives of the local branch, which has never grown to more than six Korean employees in that time, were to liaise with Korean clients, manage work between US and European offices, and grow new business locally.Footnote 5 The local CEO, who had worked in advertising agencies of large Korean conglomerates for most of his career, sought to market the reputation and global experience of the foreign partners, as well as the benefits of having employees around the world working around the clock on client projects.

Part of Limelight Korea’s duties was to reproduce the image of this seamless, bilingual, and global organization. In practice, there was a swarm of other relations involved in the construction of the firm. The company frequently hired freelance designers, researchers, and strategists, as well as subcontracted to other small-scale firms in Korea. In 2011, it started a licensee-ship with a US market research firm to carry out consumer interviews in the Korean market. It also worked alongside the official advertising agencies of Korean clients themselves.Footnote 6

This spiderweb of relations reflects two broader trends in the marketing and advertising industries globally as well as in Korea. One concerns the increasing demand for global marketing and advertising agencies in terms of geographic availability and perceived expertise. The other reflects the outsourcing and offloading of production costs from “in-house” departments to third-party firms. Limelight Korea benefitted from its affiliation with its global partners as company employees had license to draw on the experience and authority of those firms (not to mention their documents) to attract Korean clients. To many in Korea, Limelight Korea would be considered a prestigious foreign-affiliated firm (oeguggye hoesa). As an independent company employing only Korean employees however, Limelight Korea was also considered similar to local third-party firms. These smaller firms contracted with large Korean corporations, but the terms were considerably different. They were not favored as prestigious but considered as quick-production shops. Such firms had little bargaining power, had to work beyond their contracts, and frequently faced overnight deadlines. Limelight Korea’s positioning as the former global type on paper did not always prevent its construal as the latter in practice. In an indicative incident, a Limelight Korea team manager, exasperated with one of the company’s large clients who had forced onto them a number of translation requests, complained that the client thought of them just as a “translation company.”

Standing between these two poles, the CEO, team managers, and junior employees of Limelight Korea worked together to both display competency as global marketing experts to their clients and capability as managers to their partners. These two different authorities, however, did not always work in concert. Limelight’s clients were known to ask numerous favors and revisions beyond contract stipulations. This tested the relationships with its overseas partners considerably. To refuse demands, such as the request for translations above, risked losing clients or breaking the company’s seamless image. However, as the number of clients and projects increased between 2011 and 2012 leading to increasingly unpredictable work hours, employees found the need to control tasks and working hours. They did this by initiating weekly meetings, creating time and task tracking, instituting basic accounting, and systematizing document storage.

I began this article by arguing that managers had tenuous claims within the organization, relying on different ways of dealing with documents to establish different kinds of authority. However, documents and other texts also could displace other kinds of risks, like those mentioned above. In the context of a marketing industry seeking expert knowledge, access to and possession of “insider” marketing theories, templates, and other trends provided significant textual capital to Limelight Korea. Similarly, in a Korean market that put pressure, so to speak, on the vocal repertoire of individuals to produce proper English as a sign of “globalness” (Park Reference Park2009; Harkness Reference Harkness2012), access to preformed English documents, and collective composition techniques became a way to display competence on paper. Individually, both employees’ knowledge and English competence varied, but collectively as “Limelight” on paper, such differences could be pooled together, obscured, or depersonalized. Finally, disciplining office practices through forms and other trackers offered a way to indirectly control potential interpersonal conflicts over the way the company was managed. Limelight Korea and its partners came to rely just as much on the tangible dimensions of documents and paper to realize such authorities as they risked in them. In the next two sections, I turn to how office employees attempted to manage and mitigate these risks in two different styles—display and discipline.

Documents on Display: Remapping Relationships across Texts

As a brand consulting firm tasked with assessing market trends, compiling reports of competitor activities, and developing brand strategy recommendations, in addition to logo and name development, Limelight Korea collected, reproduced, and appropriated documents from other sources as much as they produced them. Some of these documents came in the form of templates from their partners that they could use freely for marketing, promotion, or proposal purposes. Others came in the form of manuals, such as those from its licensor in the United States that provided a manual on how to structure and analyze research interviews. A wider variety of genres and documents were sourced from the Internet, provided from current clients, or pulled from the personal collections of employees themselves.

As a representative of a global firm in Korea, Limelight Korea’s CEO had to ensure seamless operations with other parts of the organization. In this sense, he often sought to link authority of the company with its other more prestigious partners while erasing the relationships to its subcontractors. Hence, on paper Limelight Korea generally went by “Limelight,” dropping “Korea,” and downplaying its own status as a branch office in Korea. However, activities to delocalize its status and align with outside authorities entailed more than just borrowing others’ documents and altering the title. Employees had to attend to the social relationships between their source, themselves, and future addressees. As Urban (Reference Urban, Silverstein and Urban1996) has discussed, in instances of reproduction of discourse, actors attend not only to textual fidelity but assess the existing or perceived social relation between the themselves and the source at the same time.

Like bricoleurs of documents, Limelight Korea employees marked relationships between themselves and their sources on paper in various ways, complicated in part by the textual-visual-material medium of replication and in part by their complex social connections. In what follows, I list five distinct ways I encountered that employees modified existing documents and documentary fragments and how the intertextual linkages were highlighted or downplayed. I have categorized these as “assimilating,” “converting,” “modeling,” “associating,” and “citing.”Footnote 7 (As an emergent way for defining relationships, the potential to define relations across intertextual connections by other means is not necessarily limited to those discussed here.)

Assimilating involves aligning a token document to a template either through copying or re-creation so as to minimize the differences between the two texts and, by extension, the authors. The effect of this is to represent Limelight Korea as one and the same with its global partners, thus minimizing any organizational barriers between them. In my data, assimilating occurred primarily through visual and stylistic similarity and elision of authorship. This form of intertextual display emerged when Limelight Korea used templates, company introductions, and other background material from its partners as its own, particularly those of Limelight Europe with whom it shared many templates.Footnote 8 Such types were not publicly available but had to be authorized for use and identity alignment. The example in figure 1 displays an example of Limelight Korea using the same template for proposals as Limelight Europe with content originally developed from the European office that the Korean branch was allowed to use.

Figure 1. PowerPoint slide from a company proposal, demonstrating Limelight Korea’s use of boilerplate material, provided from the office of Limelight Europe.

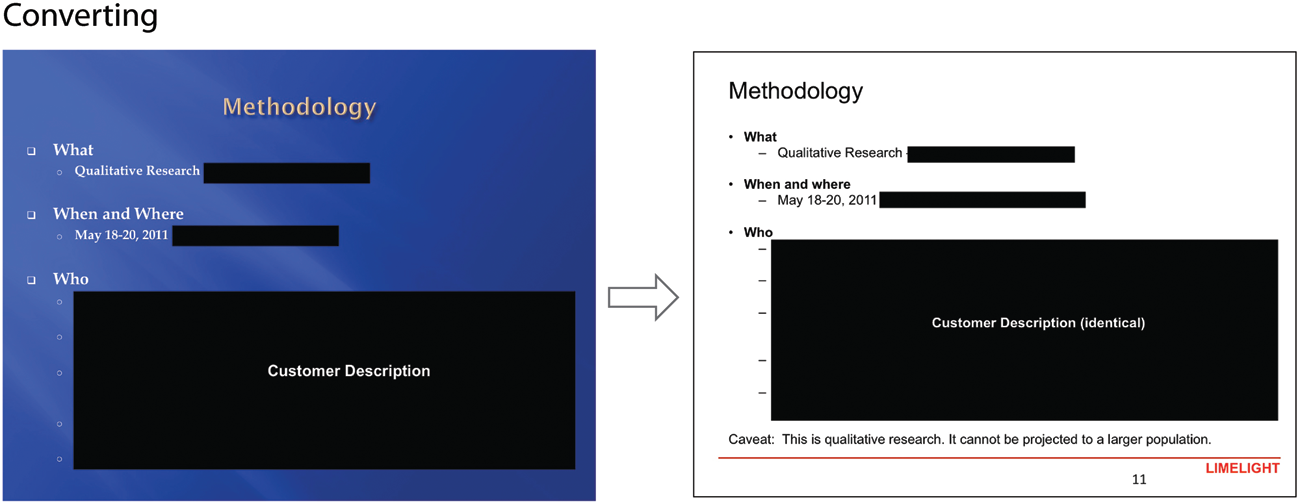

Converting involves transforming another firm’s document into a Limelight (Korea) document. Converting erases the traces of the original source, including its authorship and visual style, to represent it as a typical Limelight document. This method featured prominently when Limelight employees dealt with sub-contractors or freelancers, whose work they were allowed to present as their own. The example in figure 2 here shows the report of a research subcontractor that was converted into a Limelight document, through modifications to color and layout. Such conversions remove any direct or indirect citation from the work of the original subcontractor, so the work itself becomes an example of a Limelight template. On occasion, Limelight Korea also converted documents it did not have authority to use, as I show in the fourth section, when it borrowed the template from a prestigious American advertising agency.

Figure 2. Subcontractor document converted into a Limelight document. The gaps between the two firms have been erased so as to minimize the connection between the source and the sourcing text.

Modeling involves sourcing of visual and textual frames from source documents to organize information. Models share a similarity of visual layout, linguistic style, and/or information design from another documentary fragment such as a PowerPoint slide. In figure 3, the layout from a 2005 PowerPoint (left) became the model for describing a similar process in 2011 (right). The purpose of modeling was not necessarily to allude directly to prestigious frames; there could be a wide range of practical purposes such as motivating new ways of analyzing data, making slides ‘a little prettier’ (jom yeppeuge) in the words of one employee, making work easier, or demonstrating the company’s familiarity with other ‘famous models’ (yumyeong modeldeul) from marketing textbooks. The CEO, in particular, was fond of borrowing models from a prestigious US management consulting company that had become well known in corporate circles in Korea.

Figure 3. The layout of a 2005 PowerPoint (left) for creating an “icon brand” became the model for describing a similar process in 2011 (right). On the right, the original framework was readapted for a different client and purpose, demonstrating how to create “brand preference” and “brand leadership” among a new target consumer group.

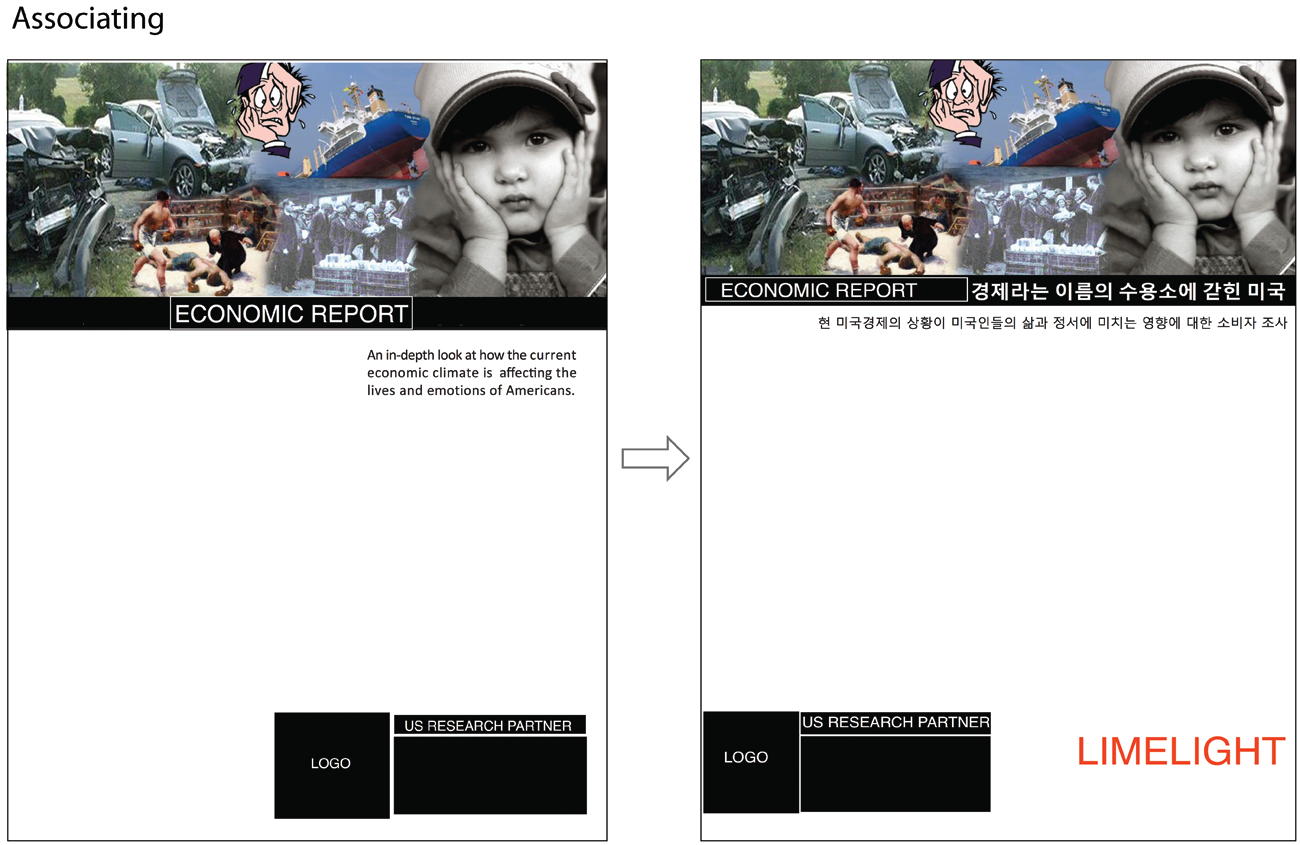

Associating involves attributing dual authorship, where the sourcing entity associates with the source author through visual copresence. Figure 4 demonstrates an example in which the Limelight Korea CEO had translated a research report on consumer behavior by its American research licensor into Korean. In the Korean version, the Limelight logo was prominently attributed on each page next to the original research company’s logo. Because the relationship between the two entities was based on a license (and not a partnership), the company did not have full authorization to attribute it as its own, as in conversion or in assimilation, mentioned above.

Figure 4. Two covers of a research report used for marketing purposes. Left: Original cover from its research partner in the United States. Right: The cover as “replicated” into Korean from the English by Limelight employees.

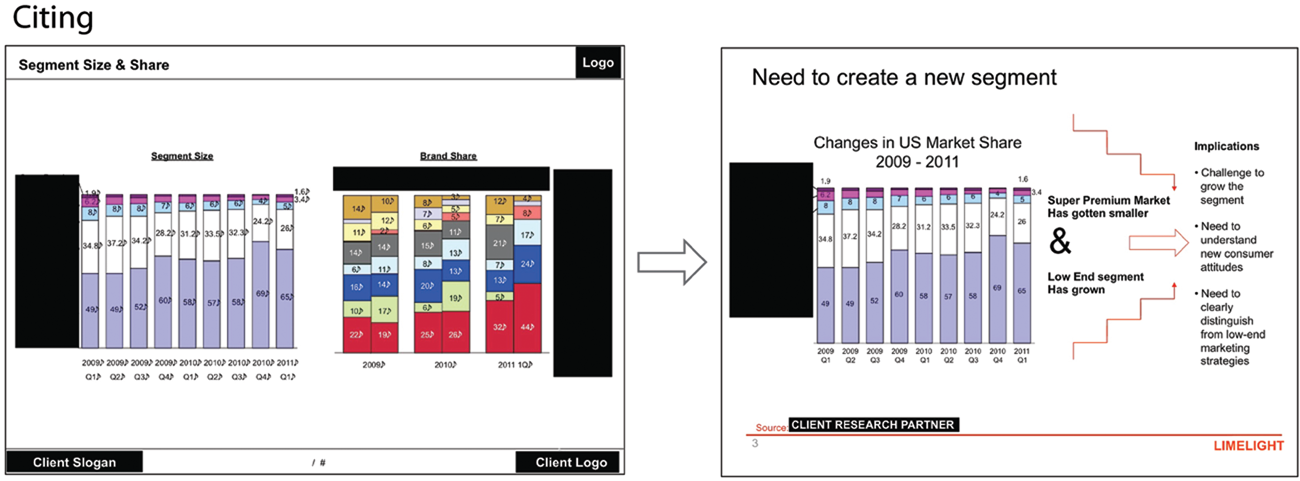

Citing involves the reproduction of a token element into another text with a citation to the original source. This form of replication represents maximal fidelity to the form of the source content while highlighting the authorial gap between them. Figure 5 represents one instance where Limelight Korea employees reproduced material from its client, citing the original source and not directly altering the content. Unlike associating, citing maximizes authorial and temporal gaps between citing and citation. The gap between the original and Limelight Korea’s work is also spatially segmented so as to diagram their relationship. Citing occurred in cases where addressees were the principals of or were familiar with the proprietary content being sourced.

Figure 5. An example of citing. Left: Graph of survey results supplied by one of Limelight Korea’s clients. Right: Reproduction of the same graphic in Limelight Korea’s presentation back to that client, with citation at bottom to the original research.

To conclude this discussion of intertextual display, I have described five ways that Limelight Korea employees managed social relations on paper by sourcing and altering content from outside sources. These relationships aligned only marginally with formal relations or legal designations but came to be defined by the value of the content, the level of familiarity of future addressees to the content, and the perceived hierarchy of relations. In certain ways, these represent a range from the minimization to maximization of the gap between comparable texts (Briggs and Bauman Reference Briggs and Bauman1992), with assimilation minimizing this gap (aligning of roles) and citation maximizing this gap (acknowledgement of an outsider’s role). Minimized gaps on paper could, however, be alluded to in nonrecorded ways, just as the CEO often revealed to me orally where the original source was and how he came to acquire a given model. As formal records of company work, however, they represent one site where the emergent and sometimes vague relationships between Limelight Korea and its myriad partners became worked out on paper. In some cases Limelight became the author and principal, and in other cases it had a secondary role, echoing the perception of their subordinate role in working relationships. If the manner by which employees dealt with these emerging roles was conducted on a case-by-case basis depending on the content and context, in the next section I look at the ways in which certain employees attempted to discipline treatment of documents and social relations through more systematic methods.

Intertextual Discipline: Creating Icons of Systematic Management

Limelight employees did not draw on external documents solely for aligning with outside sources. Externally sourced documents also came to be used to manage office activities. The way that documents were manipulated and the way intertextual connections were drawn differed from the case-by-case borrowing described in the previous section. Where any two cases of intertextual display might not be similar, intertextual discipline involved the repeated use of the same type of document to track information and regiment behavior. In contrast to the colorful and creative PowerPoint documents, documents involved in intertextual discipline largely had a bureaucratic styling. The combination of stark lines, boxes, and white spaces, along with referential textual styles in these forms, was no accident of course; they came to diagram the activities surrounding them, such as the frequency of filling them out, the process for turning them in, and the way they were labeled. Such a multimodal, multi-event process creates an iconic image of organizational systematization starting from the authority of paper out to employees and, in some cases, out to unruly clients.

This phenomenon bears traces to what is known as the “systematic management” movement in the history of the business corporation in the United States (Nelson Reference Nelson1974). In the late nineteenth century reporting techniques were developed to discipline and control newly emerging railroad and other industrial enterprises that spanned large geographic and temporal areas. In this period, managerial writing styles changed from prose-based letters to more formalized, depersonalized forms and memos. But what distinguished the systematic movement was the regularized usage of such genres across a company for the purpose of monitoring activities by managers. A well-known description of systematic management defines it as “a careful definition of duties and responsibilities coupled with standardized ways of performing these duties” and “a specific way of gathering, handling, analyzing, and transmitting information” (Litterer Reference Litterer1963, 389; cited in Yates Reference Yates1989, 10).

At Limelight Korea, the need for systematic management techniques arose as a way to handle long-term projects with Korean conglomerates. As Limelight Korea handled multiple clients and projects concurrently, the overlapping demands put pressure on other employees. One team manager, who had recently graduated from a European MBA program, advocated for internally regulating processes as a way to structure the flow of work, control time, and manage expectations with the CEO. She was the first one to institute a system for tracking tasks and time within the company.

Managing time and work task information involved instituting new processes or revising existing processes related to projects, deadlines and time spent. Before the hiring of the team manager in mid-2011, employees did conduct a regular Monday meeting where they discussed projects and tasks from the previous week and the upcoming week. But after the team manager arrived, she instituted a more formal process for reporting time, tracking tasks, and summarizing work processes.

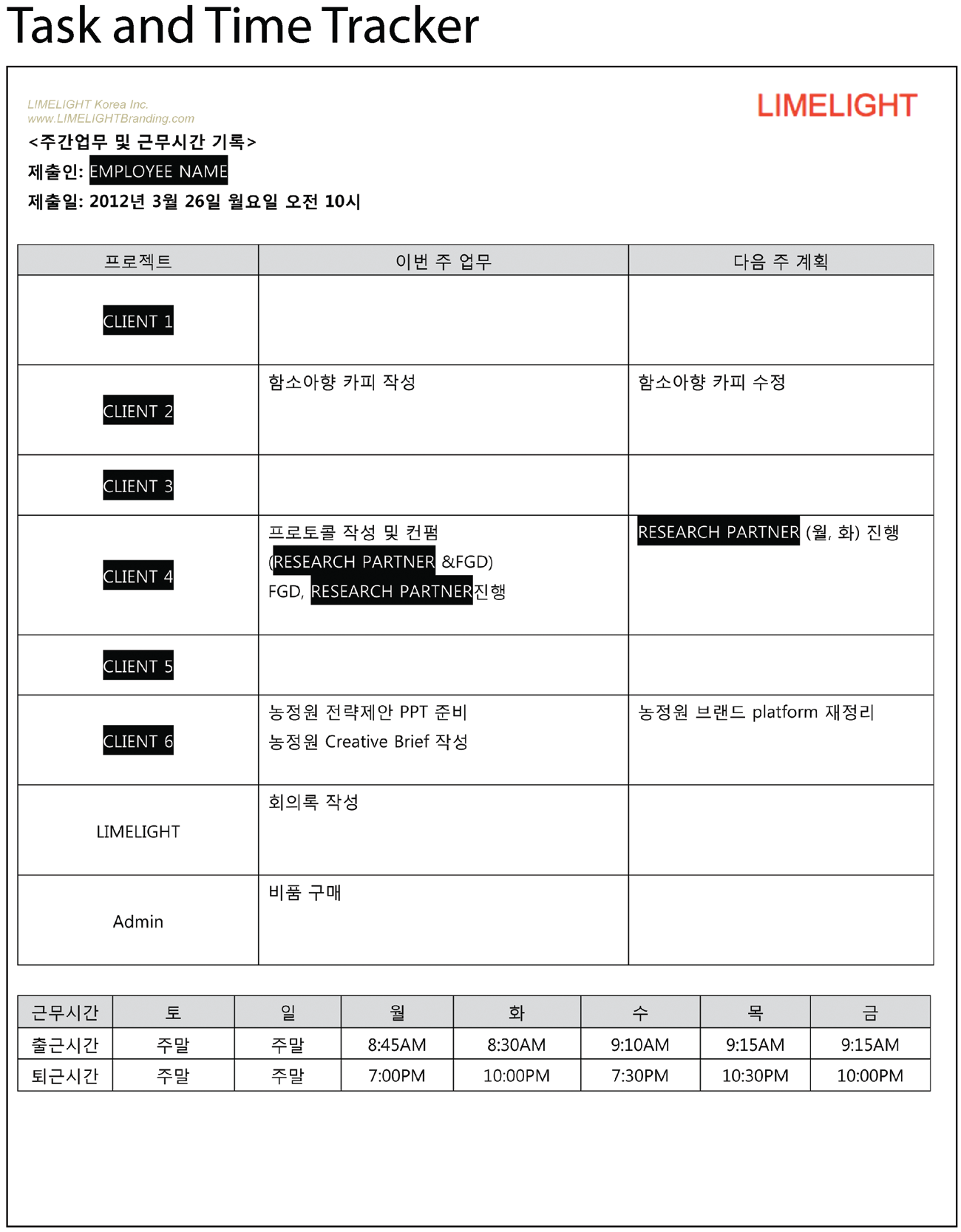

There were a number of documents involved in this process, the central one being the ‘Weekly Task and Working Hours Log’ (juganeobmu mich geunmusigan gilog), shown in figure 6. The form required junior employees to describe tasks achieved in a given week and tasks for the following week for projects they were assigned. At the bottom of the form they also wrote out their daily ‘check-in time’ (chulgeunsigan) and ‘check-out time’ (toegeunsigan).

Figure 6. An example of the Weekly Task and Working Hours Log completed by one junior employee. The clients are listed down the left side of the form. The previous week and succeeding week tasks are in the center and right columns, respectively. The employee only filled in the projects she had been assigned to.

The form has a highly referentialist focus on discrete categories—‘submitter’ (jechulin), ‘submission date’ (jechulil), ‘this week’s work’ (ibeon ju eobmu), ‘next week’s plan’ (daeum ju gihoeg), and client names. This is reinforced visually through the spartan stylization of the document. An indication of the document’s power for controlling language and worker activity is the way that employees filled out their work tasks. These categories, the empty white boxes in the middle of the page, do not explicitly indicate any way to fill them out. However, one junior employee reported that she felt compelled to write in a bulleted, noun-only style typical of Korean documents,Footnote 9 rather than full sentences because it seemed more “appropriate” than using full sentences.

Every Friday afternoon before 5 pm, each employee below the team manager filled out a blank version of the document and submitted it by email. The youngest junior employee collected the forms and compiled the task information into a unified form in advance of a company meeting on Monday. The team manager inputted the time information in an Excel sheet for her own time-tracking purposes. The team manager used the time-tracking information to monitor who arrived late and who worked overtime. If employees were late, they might be disciplined, and if they worked on the weekend, they would receive overtime pay.Footnote 10

It is possible to attribute the illocutionary force of the form and its related processes to the hierarchy of the office itself, as the team manager ranked above lower employees and could simply compel them to fill it in. It is possible too to attribute it to the consistency across literal texts, as every token instance of the form replicated a type-level normativity—an abstract, depersonalized authority rather than a real, recognized authority (such as a client). However, purely textual explanations miss the other patterns of consistency that occur across linguistic elements, visual design, regularity of usage, and even to the labeling and storage of the weekly meeting documents themselves. Hierarchical explanations miss out on the power plays within the company for competing authorities and the mode of grounding that authority. The process described in this section is indicative of one team manager’s authority—below that of the CEO—in which she attempted to control the flow of work. Consistency of use through depersonalized documents that abstract from the here-and-now linguistically but also procedurally could act as checks on the CEO and in some instances even counteract the hierarchy. For example, records of time tracking and work tasks, presented in a completely de-authored setting, could curtail the late working nights of the junior employees.

Like all forms of authority grounded in an intertextual chain, this form of authority was contingent on the chain being taken up by its addressees. In fact, when that particular team manager left the company in 2013, the formal process for collecting time-tracking information ceased while the weekly meeting kept on. The CEO was more interested in keeping track of project tasks than the regulation of internal management. Thus while the form for the meeting remained, the process for holding the meeting or filling out the form regularly began to slacken. When employees were late, one junior employee reported that the CEO just uttered “don’t be late” (jigaghajima).

Blurred Authorities: Displaying Discipline

In previous sections, I discussed two different styles of managing intertextuality. In the second section, employees elided or highlighted textual distinctions from source documents, their own, their partners, and nonpartners. In the third section, a team manager implemented a form-based process for regulating internal practices. In some ways, these differences parallel a formal distinction between “templates” and “forms.” Templates prefigure linguistic categories, visual layouts, and denotational content, but the final product erases its own trace.Footnote 11 Forms, on the other hand, impose on the user fixed content and role categories that persist in and across any token usages. The template erases itself at the moment of completion, allowing a user to take on multiple roles (such as author and principal). Forms in contrast attempt to constrain and make participant or subject categories explicit. In practice, of course, these formal distinctions become more complex. For example, as material objects or digital files, forms can be manipulated just like templates—edited, modified, combined, or copied. Individuals can also choose to ignore or even selectively read certain parts. I discuss in this section how a document that resembled both template and form blurred the lines between the two intertextual styles.

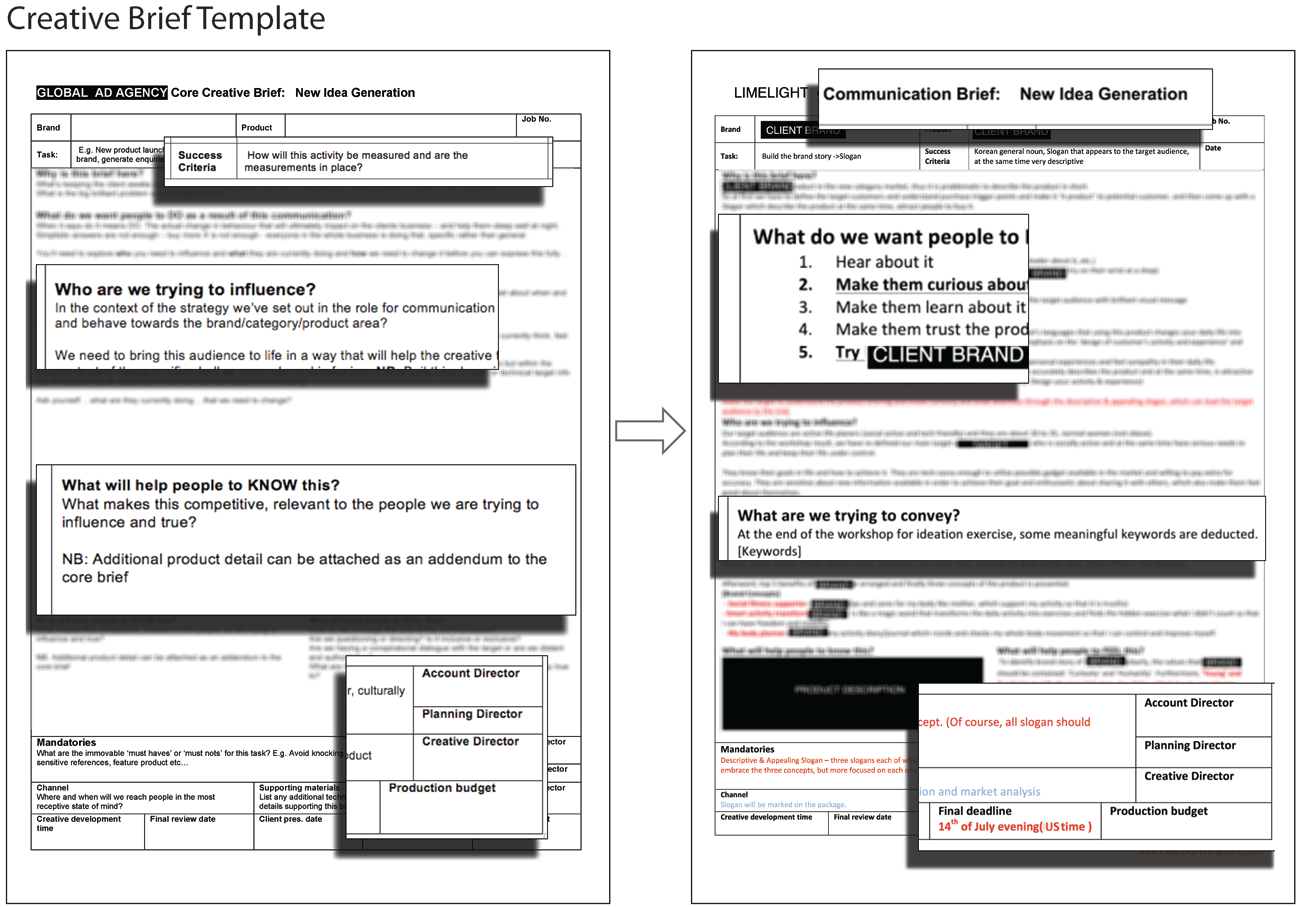

“Creative briefs” are a frequently used genre in marketing and advertising industries to guide creative content development based on strategic business goals. At Limelight Korea, when the company had a creative project such as developing a logo or name, they would use a creative brief midway through the project. Limelight Korea came into possession of a template for conducting the creative brief process from a global advertising agency. The CEO and the male team manager had previously worked together at that agency’s Korean branch. Both had retained copies of the English language template when they began working at Limelight Korea. It became a Limelight Korea document when the CEO deleted the original company name and inserted the Limelight name and logo and changed the title from “Core Creative Brief” to “Communication Brief”—an example of converting—as seen in figure 7.

Figure 7. Example of the “creative brief” in two stages. Left: Its sourced version from the advertising agency. Right: A completed version by Limelight for a health product. Because both documents contain proprietary information, they have been blurred, but certain key dimensions of this transformation have been emphasized for analysis.

I highlight here the contrasting styles of the document—both its “form”-al and template features. The formal features, framing the top and bottom of the document, cover a range of bureaucratic styles, written in the style of a voice-from-nowhere, enforced by fixed categories and rigid spacing. These features largely serve to regulate the creative brief process itself—review dates, budget, persons responsible—but within a larger bureaucratic surround—client, project, job number. These contrast with the highly evocative template content in the middle portion. This content aids and guides in generating creative ideas and even provides “instructions for use” (Harper Reference Harper1998), meant to be deleted in the final production of the document, leaving only the section headings in bold and the developed content. Such instructions not only clued the employees into what and how to fill out the document, they also structured the meeting with the client who came in for a “creative brief session” at the Limelight Korea office.

In the final version on the right, the employees took a number of creative liberties in drafting the brief’s main content and arranging the content on the page, while respecting an unwritten rule for making the content fit on one page. Equally important, however, is what they did not fill out: the formlike features of the creative brief. On one hand, they could not; Limelight Korea did not use job numbers, nor did they have formal account, planning, or artistic directors. On the other hand, they simply did not fill in dimensions of the form that were too formal: development time, review date, or a fixed production budget.

In the replication of the creative brief, employees submitted themselves to the discipline of one genre within the document—the template—while only partially acknowledging its formal aspects. Specifically, they did not fill in those categories that situated it within a larger corporate environ. However, the fact that those categories remained in the document, I argue, did much to display discipline. That is, Limelight Korea employees did not use the documents to display their closeness to an American advertising agency but rather they used it to display that their organization also had the regulating processes of a larger company. Such formal features—job numbers, titles, budgets—index an intertextual chain of regulating processes for a global company with a bureaucratic structure. For Limelight Korea, the document became a token of an internal type that did not actually exist.

Cases of style blurring occurred in other instances, too. For instance, in presentations to clients, a slide displaying a visual timeline of project deadlines would often be included. Visually mapped timelines were used to regulate clients by reminding them of past agreements through the copying and pasting of previously agreed upon charts. Including timelines with the deadlines listed was not itself enough to be able to control clients, who often chose to ignore such information, testing Limelight Korea’s time, patience, and contract terms.

To conclude this section, I make the observation that individual document styles and styles for managing across documents did not always parallel each other. Where in other instances employees altered intertextual links for practical purposes or submitted themselves to the demands of formal processes, these styles could also overlap in unexpected ways. The case of the creative brief shows examples of documentary conversion, regulation of office practices, and the display of a large corporation, all in one document.

Managing Future Intertextual Chains: Locking and Leaking Documents

I turn to the ways employees managed texts as both items to be sent and items to be stored. Document storage has been a central concern in early corporate settings since the advent of means of mass paper replication technologies (Yates Reference Yates1989). In bureaucratic settings, Hull (Reference Hull2003) has described how files pile up or are passed along as a way for bureaucrats to defer responsibility, stemming in part from the highly identifiable nature of bureaucratic recording methods. In the case of Limelight Korea, the specification of individual activities and movements was not central to employ concerns, as most internal actions were not recorded. What was a concern was the perceived value of information itself—its potential future use value to the company and its potential to be appropriated by outsiders, the very activity through which Limelight Korea employees derived considerable value themselves. Thus one of the paramount activities related to managing files (and not just texts) was the regulation of access to files.

Acting on behalf of the company, employees attempted to delimit how other companies could use documents that Limelight Korea possessed and produced. In one sense, this implied the physical guarding of both printed and digital files. In another sense, employees curtailed future intertextual usages when they had to send out files in a number of ways.

One of the most common ways involved changing file formats. An email from a client one day in 2011 advised Limelight to send all its files to the client team in “PPT” format (i.e., in Microsoft PowerPoint format) rather than in Adobe “PDF,” which they had been sending. Limelight employees were aware of the implications for sending a PPT compared to a PDF: in the case of PowerPoint files, the file was deemed to be fully editable; thus its future editing and authorship would be out of their control. In the case of PDFs, while parts can be manipulated and styles replicated, one cannot erase and substitute visual information as easily. Replication of PDFs requires fully reproducing its contents without the ability to borrow fragments. In PPTs, employees saw a risk of clients converting their documents into the client’s, thereby erasing Limelight’s presence on paper. Someone might copy their diagrams, take credit for their ideas, or put their name on the cover, just as Limelight had been astute to do from the documents in their possession. In the case of design work, the risks were greater: a client might easily plagiarize a logo or idea and cut the company out of the loop without payment.

There were other ways that employees manipulated clients’ abilities to receive fully editable copies. One was to present the document as a printed and bound report at a meeting and not allow a digital version to circulate. Another was to send a small number of people a PowerPoint and distribute a PDF copy to a wider group, delimiting authorized editors from authorized readers. The company could also delay by not sending the finalized version of a PPT until a final decision had been reached.

At an individual level, employees had developed their own strategies for future intertextual use-value. In some instances, they made their own efforts to systematize documents for the management of everyday work—such as coming up with their own nomenclature systems for files or organizing them into folders on their own computers. But they did not always heed the company line. In follow-up interviews with workers who had left the company, junior employees revealed they were highly aware that the CEO and team managers each had extensive personal archives of projects and files from prior workplaces that they referenced often. Younger employees began to learn indirectly that they should also copy documents for their own personal use before they left the company. One former employee noted that she could sense others kept databases, so she started to periodically save digital files to her external hard drive. She described saving files as ‘feeling like a souvenir’ (ginyeompumgateun neukkim) of her time at the company. An older team manager with decades of experience in the advertising industry had a more sophisticated database. Organized in hundreds of folders by client and project, his personal archive of print and TV advertisements represented his career’s work. What for the company might be an ad hoc reference to one of these documents, for him was one way of creating new value for himself as an employee, especially in an increasingly flexible Korean labor market.

Building up of credentials (called ‘spec’, seupeg) by individual workers has been a hallmark of transformations in the labor market in a post-IMF (1997–1998) South Korea. As the labor market has become more flexible, both young employees and corporate workers seek out recognized credentials through self-study and personal investment, mediated by a register of self-development (jagigaebal) (Abelmann, Park, and Kim Reference Abelmann, Park and Kim2009). English test scores, extra-work activities such as volunteering, overseas study, technical achievements, and other rank-able certifications have shifted the way that individuals orient to the job market, off-setting traditional means of employment and advancement based on school (hagyeon), kin (hyeolyeon), or regional (jiyeon) connections.

Overlooked in these discussions has been the way that employees in the job market can orient to such destabilization through cultivating databases of physical (and digital) materials from workplaces and other textual sources.Footnote 12 Like the intertextual chains mentioned in the second section in which employees erased the traces of authorship on paper, such databases also remained hidden from resumes, but provide a material record of otherwise “knowledge-based” labor that could be used at a future job. The value of such caches ultimately bleeds across both personal and corporate usages, a sign of neither pure labor-value nor corporate-property but objects of joint collaboration that may entail some future value for both.

Employees in their official capacity as agents of Limelight Korea altered the future trajectories of files by delimiting how other actors came to use them and by opening up space, figuratively and literally, for themselves to use them in new ways. Both of these methods provided a future, unknown value to the company and the employees. In larger corporate environments, particularly in Korea, employees may have only limited access to files in addition to the risk of “leaks.” For employees on the corporate periphery, possession of important documents opens up opportunities that may extend beyond safeguarding the proprietary or informational content.

Conclusion: Textuality, Role-Taking, Variation, and Imitation

This article has argued for a view of intertextuality as a mode of engaging with the textual and material transformations of circulating textual objects, their bearing on organizational dynamics, and the risks and values associated with taking different positions. Considered in this scope, the means by which individual actors can create or erase intertextual gaps differ significantly, opening up space for new styles to emerge, laden with different higher order values about managerial practice and what makes a good CEO, manager, or employee. I address in conclusion four related issues that resituate the ethnographic examples discussed in the article within other discussions regarding textuality, role taking, variation, and imitation.

The first issue concerns the nature of corporate textuality itself. Office workers are largely surrounded with entextualized objects, the relations between which they have to manage. In the second section, I described the ways in which the relations between these texts were minimized or maximized across linguistic and visual space, creating variegated degrees of likeness depending on the relation between authors and the purpose of the document. In the last section, I described how employees physically handled these texts as objects, changing their trajectories on the computer, on paper, and in face-to-face settings. Even as the corporate workforce becomes more “wireless” the dimensions by which employees have to deal with documentary storage, “cloud computing,” and ever expanding threats against leaks have not disappeared. Thus, even as texts are linguistically “detachable” from the here-and-now, the material ways in which they remain attached to their contexts of production and reproduction remain a concern.

Second, as corporate actors become adept at negotiating the relationship between texts, the management of intertextuality opens up a way to rethink how participant roles emerge within such activities. Irvine (Reference Irvine, Silverstein and Urban1996) has described how participant roles emerge in the reporting of conversations and that such roles may in themselves be both culturally defined and interactionally emergent. A number of different roles have emerged in the examples I have discussed here. The CEO often showed his adeptness with how he was able to properly attribute or erase authorship of previous texts, especially with prestigious documents from other companies. A female team manager exercised her authority across the management of texts, specifically the implementation of systematic processes with formal documents to regulate office life. And, employees prepared to become job-market navigators as they collected and organized documents over their careers. The management of intertextuality ultimately has the potential to create different kinds of managers of intertextuality.

Third, as different kinds of managers emerged at Limelight Korea across different ways of dealing with texts, there may be multiple styles and ideologies of grounding authority that are not confined to specific domains (corporations) or abstract roles themselves (management). Corporations, like organizations more broadly, can be considered as composed of different links and assemblages that are not reducible to either institutional or individualist perspectives (Weick Reference Weick1979; Tsoukas Reference Tsoukas1996). Thus authority may be dispersed across different domains that have different or even competing institutional dispositions. However, even actors within the same department or small office may carry diverging ideas about what an appropriate managerial style is. The case of Limelight Korea highlights co-occurrence of these styles in one organizational setting.

Finally, an undercurrent to discussions of intertextuality in this article has been the issue of imitation. In an economy like Korea’s that has long faced the epithet of being a “copycat” or “fast follower” economy, the case of Limelight Korea seems to present additional evidence. However, to the degree that imitation is common to all organizations, particularly in the West (DiMaggio and Powell Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983), this article has offered a more detailed way to understand how imitation operates in practice—that is, what are the meta-level ways that employees signal imitation, through what sign processes, and to what ends. Part of the reason for such widespread imitation in an industry like brand consulting, and perhaps consulting and advertising more generally, industries premised on the originality of their content, may lie in an underlying ideology that distinguishes proprietary content (such as ads, logos, or trademarks), from processual, “noncreative” content (such as templates and forms), as well as blurred lines between what is personal and what is corporate property. Such discussions, for now, can only allude at what future dimensions a semiotics of the corporation might look like and the possibilities it has for contributing to broader social scientific approaches to the practical and meaningful dimensions of organizational life.