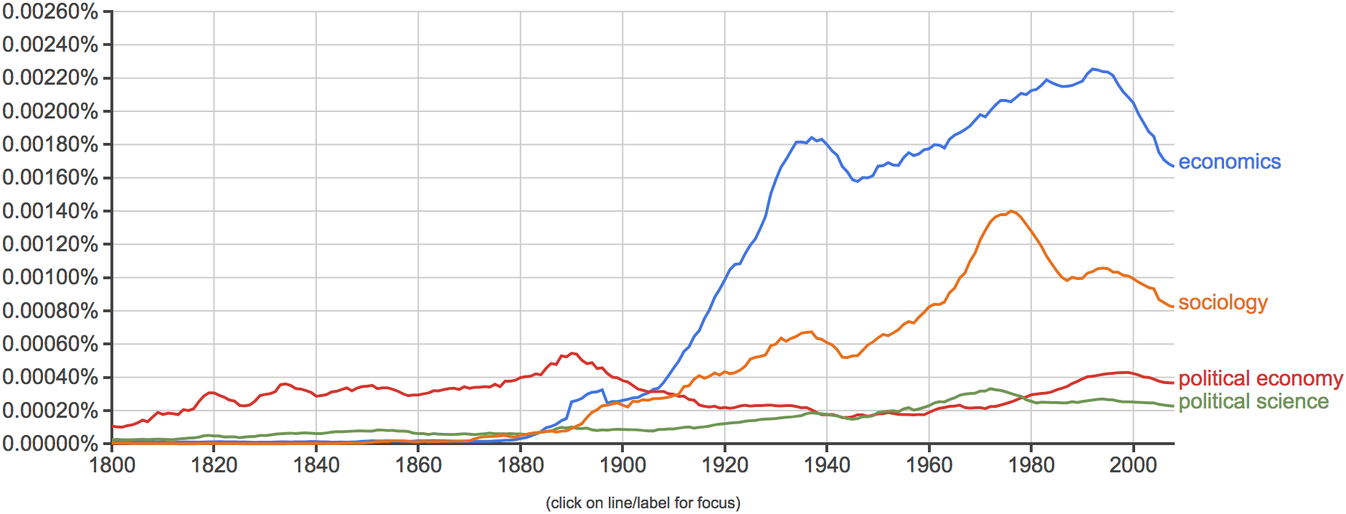

It is a stylized fact that nineteenth-century political economy had by the end of that century spawned or splintered into a variety of distinct social science disciplines. The Ngram in Figure 1 captures this well. It plots the share of references to political economy and the distinct social sciences of economics, politics, and sociology in books by the year of their publication. Political economy starts to fall away just as the latter group of disciplines begins to rise around 1880–90. Figure 1 also illustrates what is a common impression: the relative fortunes of political economy and these social science disciplines changed in the final third of the twentieth century as the interest in political economy revived. This essay is concerned with how to characterize the shift first from political economy to economics and then back to political economy. I will offer two accounts. There are some shared elements in these accounts but there are also differences, and I will argue that these differences matter. They matter for how one does social science and, more speculatively, for what is taken to be a pressing political economy problem of our time.

Figure 1. Ngrams.

I first develop what is a providential account of the shifting movements between political economy and economics. It is providential because it casts the return to political economy in the latter part of the twentieth century as the spread of the economic rational choice model to politics. Politics and economics are reintegrated or reunited on this view because the ontology (and method) of economics that became distinctive through its original split from political economy is now increasingly shared by politics. In short, it is economic providentialism. Economics first is severed from political economy, then establishes its own identity, and finally re-engineers politics in its own image to create a new kind of, what might be better called, “political-ECONOMY.” The second explanation sees the reintegration of politics and economics in the late twentieth century very differently: the return to political economy occurs because economics finds that it needs to recover some part of what it lost in its model of human action when it emerged as a separate discipline at the end of the nineteenth century.

Thus the difference between accounts turns, in some sense, on whether the original move to economics in the late nineteenth century is vindicated or vanquished by the subsequent revival of political economy in the late twentieth century. Was the severance a stepping-stone in a story of progress or “a bit of mistake” that needed rectification? After setting out the claims of both accounts in the next two sections, I turn to why this dispute matters in the last two sections.

I. Providential Economics

The providential account is, I suspect, the one most commonly held. Political economy succumbs to the logic of the division of labor. This is ironical, perhaps, in the sense that political economy identified the division of labor as the motor of most things, and this process of division was then applied in the academy to the discipline of political economy itself. Adam Smith would not have been surprised, as he thought the logic of the division of labor applied as well to the production of knowledge as to pins.Footnote 1 Political economy thus spawns the distinct disciplines of politics and economics (and sociology) because there are advantages to this for each new discipline as the productive logic of specialization takes hold. However, as Smith also noted, it tends to create a problem of coordination between what were hitherto integrated forms of activity. For production, the institution of the market does the coordinating, but what does this in the academy and the realm of ideas?

Of course, one might wonder whether coordination matters in the same way in the academy as it does in the economy. To make a table, you need to bring together the talents of those who fell trees, those who turn them into wood, those who dig minerals and smelt and cast them into screws, nails, hammers, and so on. Is the same true of politics and economics? Politicians, one might argue, surely draw on the insights of both politics and economics when first proposing policy to an electorate and then selecting and enacting policy as officeholders. They are the coordinators.

The problem of coordination arises, however, in a slightly different and epistemological way in the academy. In effect, when economics becomes disconnected from politics, the discipline of economics has to take the political context of the economy as given. Whatever is the political framing of economic activity through institutions of one kind or another, they are exogenous to economic, analysis of the economy, qua economic. The economic analysis takes place under this assumption. This is fine. The economist need pay no attention to politics as long as the political framing is genuinely exogenous: that is, it does not change when something economic changes; there are no important interconnections. If the politics were, instead, to become in one way or another endogenous to the behavior of the economy, then this strict separation threatens to undo the economic insights, qua economic, because there are feedback mechanisms that get overlooked by an economic analysis undertaken in isolation from the politics.

This last consideration was, roughly speaking, what underpinned the Lucas critique of policy in the 1970s.Footnote 2 His solution was to base macroeconomics on what he took to be something that was genuinely exogenous: individuals with given preferences who act so as best to satisfy those preferences (that is, the rational choice model). I return to the centrality of exogeneity later. For now what is important is that Robert Lucas’s famous critique connected with what were already important developments regarding, for example, rent seeking and rational ignorance coming from James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock who had founded the (Virginia) Public Choice School in politics on the same rational choice model as economics.Footnote 3 Gary Becker had been doing the same in Chicago for other aspects of social life ranging from discrimination, through the changing division of labor in the household and “rotten kids,” to immigration and crime.Footnote 4 The new institutionalism of Douglass North, Oliver Williamson, and others flourished in the 1980s as they similarly set about explaining how institutions develop using the rational choice model, taking a lead from that eminent Chicago economist of an earlier generation who, incidentally, had also passed through the University Virginia in the early 1960s: Ronald Coase on transaction costs.Footnote 5

This is the outline of the providential story—how Virginia and Chicago led economics back to political economy by bringing politics and, to some extent, sociology into the rational choice/economics fold. Political economy is thereby reconstituted around economics and the rational choice model.

There is some quantitative evidence in support of this story in the Ngram data of Figure 2. This plots again the incidence in books by year of publication of key terms in this putative change. “Public Choice” and “Rational Choice” are rising precisely as the fortunes of political economy have begun to revive in Figure 1. (I have also put in behavioral economics for a different reason. At this stage, I merely observe that by 2000, or somewhat earlier, the driving elements in this providential political economy revolution were retreating while behavioral economics was powering ahead, albeit from an initial negligible level in 1990.)

Figure 2. Ngrams.

As plausible as the providential explanation is in these respects, there is one aspect that sits uneasily with the historical record. With a division of labor and the emergence of separate disciplines, one would expect that the focus, in terms of the object of study, of economics as a separate discipline in some degree narrows and changes with its separation from political economy. After all, the material of political economy is now shared across several distinct disciplines as the division of labor takes hold, and economics should not be doing what political economy always did. Did this occur? Not obviously, I suggest.

The giants of political economy—Smith, David Ricardo, Karl Marx, and J. S. Mill in his Principles of Political Economy—are clear about the object of study in political economy: it is wealth creation. One can argue that economics in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century initially makes the question of value central, whereas this question was always subordinate to the question of growth in classical political economy. Indeed, value really only arises in Smith and Ricardo as a sideshow in explaining how markets function. So, there is a change in emphasis at the end of the nineteenth century, but once Kenneth Arrow and Gérard Debreu settle the matter in the early 1950s, value again comes to resemble something like a sideshow within the discipline. The last flourish around this topic was the Cambridge Capital Controversy of the late 1960s; but this was short-lived. What has remained throughout the history of economics, as a separate discipline, is an abiding concern with efficiency—that is, how we get more from the resources that we have. This can be understood statically or dynamically, but this is wealth creation by another name. For this reason, it is not obvious that the providential story really passes this aspect of the historical test.

II. THE PRUDENTIAL POLITICAL ECONOMY

I call the second account prudential in a nod to Hume. He is going to be my key source. I choose him deliberately (and subversively) because he is often taken to be the father of the economic approach on most things: for example, by making reason the slave of passions, he is the philosophical warrant for the preference-satisfying model of rational choice; scratch most economists and they will rehearse a form of Humean skepticism over causation; and they find solace in his sharp is/ought distinction when pressed to defend the separation of positive from normative economics.

The part of Hume that I want to develop for the purpose of this essay is well known. It begins with his discussion of the artificial virtue of justice.Footnote 6 We can see, he argues, how our interests are best served by restraining their unbridled pursuit because we fare better when we are guided by rules of justice in dealing with each other. Otherwise there is nothing “to counter balance the love of gain, and render them fit members of society, by making them abstain from the possessions of others.”Footnote 7 These rules are not natural and that is why justice is an artificial virtue: “there is no passion, therefore, capable of controlling the interested affection [in others’ possessions] . . . .”Footnote 8

In the later section “On Government,” he rehearses his earlier argument concerning the benefits that flow from following rules and then adds that these benefits are best seen at a distance: “When we consider any objects at a distance, all their minute distinctions vanish, and we always give the preference to whatever is in itself preferable, without considering its situation and circumstances. This gives rise to what in an improper sense we call reason . . . .”Footnote 9 The difficulty is that when confronted by the actual or immediate setting, the power of self-interest is too strong: “Men are not able radically to cure, either in themselves or others, that narrowness of soul, which makes them prefer the present to the remote.”Footnote 10 In smaller societies, he earlier argues, sympathy may check this “narrowness of the soul,” but in complicated and dynamic societies, sympathy won’t do the trick. We (they) need government.

They cannot change their natures. All they can do is to change their situation, and render the observance of justice the immediate interest of some particular persons, and its violation their more remote. These persons, then, are not only induc’d to observe those rules in their own conduct, but also to constrain others to a like regularity, and inforce the dictates of equity thro’ the whole society.

But this execution of justice, tho’ the principal, is not the only advantage of government . . . government extends farther its beneficial influence; and not contented to protect men in those conventions they make for their mutual interest, it often obliges them to make such conventions, and forces them to seek their own advantage, by a concurrence in some common end or purpose . . . Thus bridges are built, harbours opn’d . . . .Footnote 11

In this way Hume brings politics and a form of social rule-following into individual psychology. We have to sign up for government and rule-following because justice is only an artificial virtue. Had it been a natural virtue, there would have been no need for this.

It matters, for the plausibility of this account, that rule-following becomes a feature of our psychology. It is not enough, as it might have been for Hobbes, that we create government with powers to enforce rules (covenants need swords) and so make following the rules simply a matter of doing what is in each person’s interest. This is because government enforcement of the rules is only practically possible when we largely abide by the rules with sufficient frequency on other grounds (or for other reasons). If we did not regard the rules as legitimate and so binding on ourselves without the threat of government sanction, the size of the necessary apparatus for monitoring and sanctioning would be too big to be practical. Thus Hume, to convince, has to make rule-following a part of our psychology and he can only do this by creating a kind of (artificial) preference for doing this. Others might expand the concept of reason, but not Hume. He is already committed to “reason being the slave to our passions” and so reason for him will only make us follow rules if this serves our passions.

Some have tried to explain rule-following as rational in the Humean sense without inserting rule-following more deeply into the “passions” or preferences of people. Gauthier is a famous example.Footnote 12 He makes such “constrained maximization” a dispositional choice by “straightforward” maximizers whenever a greater benefit is thereby gained by being this particular kind of rule follower. The trouble is that if “straightforward maximization” explains the disposition of rule-constrained maximization, it will also warrant deviation from the rules whenever this serves the immediate interest of straightforward maximization; and unfortunately it often does. We need a commitment device to avoid the consequent unraveling of the “constrained” disposition.Footnote 13 When reason is cast as the slave of passions, then it cannot be reason; the commitment needs to be anchored in individual psychology by a “passion” (that is, a preference).Footnote 14

Hume appears to offer two candidates that might do this work. One is suggested at the beginning of his discussion of justice: an appreciation of common interests that motivates.

It is only a general sense of common interest: which sense all the members of the society express to one another; and which induces them to regulate their conduct by certain rules

The other comes from his discussion of convention where a history of abiding by a convention (a rule) creates expectations; it is a desire to avoid undermining these expectations that explains why people follow the rules.Footnote 15 In both cases, people have motives for acting that are oriented not only to their interests but also to the interests of others (either strongly when it is common interests or weakly when it is the expectations of others).

This is the lynchpin for my prudential account. I connect the political economy of Hume with the revival of political economy over the last thirty-odd years, by associating that revival with the (re)discovery of “social preferences” in the behavioral economics literature.Footnote 16 This is why the Ngram evidence in Figure 2 contained behavioral economics as one of the categories. I will say more in the next section about this evidence and why it marks a departure from the rational choice model. For now, suffice it to say that the experimental evidence suggests that our behavior is frequently other-regarding in a rule-like manner that Hume would have endorsed. In this way, it is possible to view the recent development of behavioral economics as indicative of a revival of political economy because I am associating nineteenth-century political economy with a model of agency according to which rule-following is important, and it is this aspect of agency that got lost when economics separated from political economy in the late nineteenth century. The contemporary revival, in other words, is a rediscovery of something that was lost.

What is missing from this thumbnail sketch is why the rediscovery of other-regarding or social preferences should be viewed as re-capturing something political and, so, marks a (re)turn that can plausibly be labeled “political economy.” To put this slightly differently, why make Hume’s rule-following something that has a political character and so potentially or plausibly constitutive of nineteenth-century political economy qua political economy? The connection with government in Hume that I have sketched is one reason for thinking that following rules in complex societies is bound up with with the existence of a distinct domain of politics. This makes the connection with politics palpable, if a bit vague.Footnote 17 One can also note that shared rule-following conduces to a kind of collective action among those following the rule, and the business of politics is collective action. There is also the analysis by economists and political scientists that distinguishes some parts of the contemporary revival of political economy and which turns on an appreciation of the role of norms in the connection between politics and economics.Footnote 18 However, I want to turn to another, stronger, more philosophical and suggestively practical reason for this link; it is found in the work of Alexis de Tocqueville.Footnote 19

Tocqueville is the perfect complement in this respect. He comes to America and needs to understand how a society that is individualist and consequentialist and deeply egalitarian can function without the leadership of an aristocracy. The leadership of an aristocracy matters for Tocqueville precisely because an aristocratic orientation is in part defined by the virtue of acting non-instrumentally—that is, acting in a manner that does not overtly adhere to rational choice. (Some) aristocrats do not succumb to the ruthless logic of acting on one’s own interests and so can become a vehicle for the encouragement of rule-following.

In effect, Tocqueville asks, “How does America do it without the aristocrats?” It manages, he suggests, through a form of enlightened self-interest that comes from the experience of an extraordinary range of civic association. It is the constant engagement of people in building “the bridges and opening the harbours” that Hume refers to above. Success in joint enterprise builds the habit of being guided by a self-interest that is informed and qualified by the general interest. What makes Tocqueville the perfect complement is his argument that the origin of these practices of civic association for him is political participation. Politics is what seeds civic association.

There is only one country on the face of the earth where the citizens enjoy unlimited freedom of association for political purposes. This same country is the only one in the world where the continual exercise of the right of association has been introduced into civil life, . . . . In all the countries where political associations are prohibited, civil associations are rare. It is hardly probable that this is the result of accident; but the inference should rather be, that there is a natural, and perhaps a necessary connection between these two kinds of association . . . .In civil life every man may, strictly speaking, fancy that he can provide for his own wants; in politics, he can fancy no such thing. . . . Thus political life makes the love and practice of association more general; it imparts a desire of union, and teaches the means of combination to numbers of men who would have always lived apart.Footnote 20

Tocqueville is not alone in making this connection. Mill makes the same argument.Footnote 21

Still more salutary is the moral part of the instruction afforded by the participation of the private citizen, if even rarely, in public functions. He is called upon, while so engaged, to weigh interests not his own; to be guided, in case of conflicting claims, by another rule than his private partialities; to apply, at every turn, principles and maxims which have for their reason of existence the general good. . . . Footnote 22

With this warrant from Tocqueville and Mill, I shall conclude my claim that the generalized rule-following, that was so important in Hume and which we find again in behavioral economics, has a political dimension; and it is the basis for a different story on the relation between political economy and economics. Such rule-following was lost when economics severed from political economy in the late nineteenth century and it has been re-discovered in the strand of the late twentieth-century revival of political economy associated with behavioral economic insights.

III. The Contest Between the Providential and Prudential Accounts

As I hinted in the introduction, the providential and prudential accounts have elements in common. So they are not entirely competitive. Both, for example, see the articulation and elaboration of the rational choice model as marking the late nineteenth-century division. Likewise, I do not want to suggest that we must choose between the two accounts when trying to explain the late twentieth-century revival of political economy. That revival has origins both in the colonization by Virginia and Chicago economists of the other social science disciplines and in the emergence of behavioral economics as a distinct and vibrant new field within economics. In this sense, the contemporary revival owes something to both accounts. Where there is a competition, however, is over the model of individual agency that each account offers. They are not compatible, and hence the way forward, implicitly if not explicitly, requires a choice. This is why the question “Which is right?” arises. And it matters.

The incompatibility may not be obvious because the behavioral insights regarding rule-following have typically been expressed in terms of people being motivated by their “social preferences.” In this way, it seems the behavioral insights can be simply assimilated into the rational choice model through a “new” class of preference. The rational choice model has always been helpfully quiet with respect to the character of people’s preferences. Preferences can be social, selfish, a bit weird or unusual, or even spiteful. What matters for the rational choice model is that preferences can be taken as given, not their character. Preferences must be exogenous. I referred to this earlier when discussing the Lucas critique, but it has always been central to the Providential account. This is clear in the foundational texts of the public choice school and in Stigler and Becker’s famous “De gustibus est non-disputandum.”Footnote 23 Brennan and Buchanan make the point succinctly:

On the basis of elementary methodological principles it would seem that the same model of behavior should be applied across different institutions or different sets of rules. The initial burden of proof must surely rest with anyone who proposes to introduce differing behavioral assumptions in different institutional settings . . . If an individual in a market setting is to be presumed to exercise any power he possesses (within the limits of market rules) so as to maximize his net wealth, then an individual in a corresponding political setting must also be presumed to exercise any power he possesses (within the limits of political rules) in precisely the same way.Footnote 24

However, this is exactly where the Prudential account represents a challenge. The behavioral evidence suggests not only that we have social preferences, but also that they cannot be taken as exogenous. They “come and go” depending on the social and institutional context. For example, there is a large experimental literature suggesting that our pro-sociality tends to disappear when, what is the same decision, is made in market setting as compared with a non-market one.Footnote 25 There is also experimental evidence that reveals an in-group bias in our pro-sociality and this cannot be reduced to a taste for discrimination because an individual’s in-group bias in one decision problem does not predict well their in-group bias in another.Footnote 26

To bring out why this lack of stability in preferences matters, consider the standard rational choice explanation of why an exchange takes place in the institution of the market, say, rather than some form or hierarchical organization. It is because one arrangement, through having lower transaction costs, enables the parties to this exchange to better satisfy their preferences. The preferences are antecedent to the exchange and become the anchor on which the burden of the explanation turns. However, if our social preferences change, as they often seem to do in experiments, when the same exchange is organized in a market as compared with a non-market setting, then there is no such anchor in antecedent preferences. Institutions are no longer simply instrumental, regulative devices. They are, in part, also constitutive. They help make who we are.

For the purposes of explanation, in other words, we can no longer explain the selection of one institution rather than another with reference to the exogenous preferences of the parties to the exchange. And from the prescriptive point of view, we cannot use the standard of preference satisfaction to recommend one institution over another because the preferences are endogenous. The choice becomes, instead, in part a choice of who to be (that is, what preferences to have); and thinking about this type of choice requires a different language from that of preference satisfaction.

This is one reason why the two accounts cannot be blended. It is important because the type of explanation and prescription developed in political economy will turn quite fundamentally on which version of political economy is selected. In the next section, after summarizing the argument, I give another more speculative reason for why the difference between these two accounts matters for contemporary politics.

IV. Conclusion: A Summary and Another Reason Why It Matters

To summarize the argument, I have sketched two accounts of the historical relation between economics and political economy. The important difference between these accounts emerges in how they understand the contemporary revival of political economy. In the providential one, it is the crowning of the rational choice model in social science as it spreads from economics to the other social sciences that marks the contemporary revival of political economy. As such, political economy, like economics, crucially takes individual preferences as exogenous. Preference satisfaction is what motivates us to act and, in this enterprise, reason is their servant.

On the other prudential account, the revival of political economy entails a recovery of a more complicated and problematic model of individual action that got lost when political economy morphed in the late nineteenth- and twentieth centuries into economics. This model entails rule-following. It deserves the title political economy again because politics is about taking collective action, and following rules conduces to a type of collective action. Such rule-following, it is also claimed by Tocqueville and Mill, is rooted in participating in political decision-making. It is nevertheless problematic because a well-accepted account of the motivation in rule-following is lacking. There is nothing akin to the formal model of rational choice in this respect. The language of social preferences is useful in the service of translation, but it is not itself a different account of motivation.

What then, one might ask, to sharpen the point of comparison with the providential account in a different way, is exogenous on the prudential account? The practices of the time and an enquiring spirit is, perhaps, the best answer that can be given. It is the one that I have sketched through the appeal to Tocqueville. But the question betrays a deeper difference. The rational choice model is formally elegant and tractable because it can divide variables into those that are exogenous and those that are endogenous. The one explains the other. The providential account is messier precisely because the distinction is not so clear, and as a result it is more likely, I suspect, to offer a kind of historical explanation that is alert and messy in the detail, rather than crisp in comparative static insights that are elegant in their simplicity and formality.

Why might this matter? I have offered one reason in the last section. The character of explanation and the criteria for making prescriptions in political economy depend critically on whether we can take preferences as exogenous. The providential account makes them exogenous while the prudential one makes them endogenous. Preference satisfaction is as a result in charge of explanation and prescription in the one but not in the other. I shall conclude with another more speculative reason that brings the dispute to the heart of a contemporary issue in politics.

The issue is the rise of populism, the decline of truth as a currency of political debate, and the polarization of political debate.Footnote 27 Emotion, feeling, and motivated beliefs are (apparently) now in ascendance. I shall take this description, uncritically for the purpose here, as a distinguishing feature of contemporary politics.

The further background idea that I need is that the business of practical politics in making collective decisions consists of two broad activities. One is the discovery of opportunities or projects where collective action serves all or most people’s interests. This is the bit of politics that “sniffs-out” positive-sum activities through collective action: things like a common defense and police force for securing property rights and public health initiatives like clean water and clean air that make people much less likely to suffer from a range of infectious diseases, cancers, and calamities like global warming. The other activity is settling distributional indeterminancies: the “Who gets what?” question that is decided through tax policies and decisions over what and where to make public expenditures. This involves resolving what are in an essential respect zero-sum interactions: if one person or group gets more, it comes, at least to some degree, at the expense of another person or group who gets less.

The two activities in politics make different demands on facts and the test of the truth. The facts matter deeply for the first type of business. We need to know, for example, whether climate change is occurring as a result of global warming before we can sensibly decide on taking collective action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Facts are not important in the same way for the second zero-sum activity. The facts may be important in distinguishing whether and what the trade-off is between inequality and growth, but, once this is known, the facts do not help in deciding whether your interest or mine should be favored (that is, how to weight the inequality aspect of such a trade-off).

One way, therefore, of understanding the contemporary drift of politics toward emotion, the decline of facts, and rise of polarized motivated reasoning is that the (perceived) balance within our politics between these two broad activities (the positive and the zero-sum ones) has shifted in the direction of the zero-sum distributional ones. This is not implausible. Growth has slowed at the same time as inequality has increased in most rich countries over the last thirty to forty years, and these two trends seem more likely to make the zero-sum side of life more salient.

It is in this context that I want to make two remarks about the possible significance of the line of dispute between the providential and prudential accounts over the role of social preferences and whether preferences are exogenous. I have identified the prudential account with the centrality of rule-following and the endogeneity of preferences. This makes the prudential account a natural ally in combatting the contemporary drift to a polarized, emotion-fueled politics for two reasons. First, it is the appreciation that we are or can be rule-following that, for Hume at least, opens up a range of positive-sum activities. In this way it potentially helps make this side of politics more salient.

Second, rule-following and the malleability of the rules create the space for resolving the zero-sum side of politics through the application of these rules. To be a rule follower, and to know this, is to know also that the rules are movable: they are highly contingent, they are never absolute (justice is an artificial virtue, remember) and so the rules must always be open to debate and discussion when rule-following is self-consciously understood. In contrast, if preferences are treated exogenously and my preferences conflict with yours, there is not the resource for compromise that comes from naturally discussing the rules we might be following. The only resource that we have is to reflect on the strength of our own preference and rely on displays of emotion to carry the day in our favor. Polarization seems more likely to be built into politics as a result.

This sketch makes the earlier argument over the division between providential and prudential versions of contemporary political economy crucial. If the argument that the providential account cannot assimilate rule-following via social preferences without giving up the exogeneity of preferences is right, then something has to give. If providential is not to become the prudential, then it will have to be the malleable social preferences. In short, we have reason to prefer the prudential version of contemporary political as it unambiguously supplies a resource—rule-following—for combatting polarized politics.

If for these reasons the prudential account is a reliable ally in combatting the drift to a polarized, emotion-fueled politics, a natural question arises: Could the providential strand in the revival of political economy have contributed to the drift in the first place? This is not the place to tackle this question seriously. Since rule-following in individual agency is what makes the prudential account useful in combatting the drift, the question is really whether, in practice, the providential account eschewed or downplayed rule-following because it was committed to the exogeneity of preferences. It is perfectly possible that the exponents of the providential account, in practice, often spoke with two voices on this matter, especially as the evidence on the movability of social preferences is relatively recent. So the conclusion is not self-evident. This is why a proper answer requires more forensic analysis than space now allows. But I will conclude with two pointers to why I am worried that the providential account might well have contributed to our contemporary malaise.

The first follows directly from the Tocquevillean sociological argument I have sketched above---that we come to internalize the practice of rule-following through political participation. The point is simply that with headline messages from key exponents in the development of the providential account, like “rational ignorance” and “Why vote?” would it be any wonder that political participation has fallen and with it our inclination to think in terms of rules? The second is a challenge that Sonja Amadae has recently issued in what is a controversial thesis linking the rational choice model with the rise of neo-liberalism.Footnote 28 Her challenge concerns how economists teach the prisoner’s dilemma. The background is an argument, in effect, that classical liberalism assumed that people would be constrained by the no-harm principle in the exercise of their liberty, whereas neo-liberalism is marked by an unalloyed rational choice understanding that people are not constrained by any mental rule of this kind. They simply pursue their interests willy-nilly. As a result, with neo-liberalism, defection is the only possible action in the prisoner’s dilemma. If the interaction is, indeed, well described as a one-shot prisoner’s dilemma. Her challenge, then, is to ask: When did you last hear any rational choice economist explain, when teaching the prisoner’s dilemma, that defection might, at least on some readings, breach a no-harm rule and therefore be inadmissible to those of a classical liberal persuasion?

If the answer is approximately never, which is my experience, then one might have reason to think that the teaching of the rational choice model has in practice crowded-out notions of (rational) rule-following that are or were part of the liberal tradition. The result is that in interactions like the prisoner’s dilemma we do not see the positive sum opportunities that might come from cooperation; instead we defect and find ourselves too often in the zero-sum world that is, to coin a phrase, “nasty, brutish, and short.”