Introduction

In Europe and beyond, policymakers have placed child poverty on the policy agenda; statistics from Eurostat (2019) reveal that 18.6 per cent of children were living in households below the threshold for being at risk of poverty in 2017. In Norway, this percentage is 10.8, which is significantly lower than the average in EU-27 countries, but it has increased over the last decade. The main explanation for this adverse development is a growing immigrant population with a lower employment rate (Epland, Reference Epland2018).

Policies to reduce intergenerational transmission of poverty and improve children’s future opportunities are an essential part of the EU’s recommendation against child poverty. The recommendation includes several integrated pillars of intervention: ensuring children’s access to adequate resources through benefits, parental employment, affordable housing and services; ensuring children’s access to education and childcare; and increasing children’s participation through sports, culture and play (Frazer and Marlier, Reference Frazer and Marlier2017). To address poverty among children and families at national levels, several European countries have implemented family intervention projects (Ball et al., Reference Ball, Batty and Flint2016). Characteristics of these projects are a comprehensive perspective through simultaneous follow-up of several target areas and family members, assignment of a key worker with low caseload and the coordination of services. The aim of these projects is often to decrease intergenerational poverty, and, in some cases, to also reduce risks of antisocial behaviour, such as criminality, domestic violence or substance abuse (Ball et al., Reference Ball, Batty and Flint2016).

Nevertheless, there is a lack of research regarding the benefits of family interventions. Many studies have been qualitative (e.g. Bond-Taylor, Reference Bond-Taylor2015; Sen, Reference Sen2016; Wills et al., Reference Wills, Whittaker, Rickard and Felix2016) – few analyse their effectiveness, and if they do, the quality of the evidence seems to be limited or poor (Isokuortti et al., Reference Isokuortti, Aaltio, Laajasalo and Barlow2020). Also, there is a lack of knowledge regarding how family intervention programmes operate and how various programme elements contribute to their effectiveness (Malmberg-Heimonen et al., Reference Malmberg-Heimonen, Tøge and Fossestøl2018). Scholars have further advised that the research should acknowledge multiple outcomes and apply experimental methods when assessing effectiveness of intervention (Batty and Flint, Reference Batty and Flint2012). To respond to existing knowledge gaps, this study analyses the implementation of a Norwegian family intervention model (the HOLF model), that included manuals, tools, schemes and supervision to structure and systematise the follow-up, relative to family intervention practices that were developed in local contexts. Four target areas of intervention were simultaneously assessed in the study: parental employment, the financial and housing situations of the family, and the social inclusion of children. The hypothesis of the study was that family coordinators implementing the manualised HOLF model (including tools, schemes and supervision structures) produce more favourable outcomes than family coordinators implementing local family intervention practices (Malmberg-Heimonen et al., Reference Malmberg-Heimonen, Tøge and Fossestøl2018). By comparing the implementation and effectiveness of the manualised HOLF model with locally developed family intervention practices, this study contributes to increased knowledge of how family intervention projects operate.

Previous studies of comprehensive family intervention projects

Much of the knowledge base in Europe regarding comprehensive family interventions derives from the UK, especially through the governmental initiatives of Family Intervention Projects (2007 to 2011) and the Troubled Families Initiative (2012 to 2021) (Ipsos MORI, Reference Ipsos2019). The pre–post study of Family Intervention Projects reported that they contributed to lower criminality, better relations in the families, decreased substance abuse and a lower number of housing enforcement actions. However, one of the weakest developments was for labour market participation: while at the beginning of the project 68 per cent of families were workless – that is, not in work, training or education – this had only decreased to 58 per cent at the follow-up, eleven months later (Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd, Wollny, White, Gowland and Purdon2011).

The Troubled Families Initiative is the successor of Family Intervention Projects in the UK, with the aim of improving the situation of disadvantaged families. As was the case with Family Intervention Projects, within the Troubled Families Initiative as well the families’ have a key worker who follows up the whole family, within several target areas, and this key worker is also intended to coordinate the services. The Troubled Families Initiative has defined criteria for eligibility, and participating families should fulfil at least two of the six criteria: problems with crime and anti-social behaviour, children who have not been regularly attending school, children who need additional support, families experiencing or at risk of worklessness, problems with domestic abuse, and parents and children with a range of health needs (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, 2020). The first study of the Troubled Families Initiative (2012 to 2015) revealed that coordination was difficult, there were varying local practices and it was not possible to uphold a high quality of programme implementation within ordinary practices. When investigating the families’ situation twelve to eighteen months after recruitment, researchers found no significant effects on parental employment, welfare recipiency, children’s participation at school or the families’ contact with child welfare (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017).

After the study there were discussions about the significance of the findings (Cook, Reference Cook2016). As a consequence, the UK government initiated a new study of the same programme, this time with a stronger research design and data sources. However, the results from this new study were in line with the previous. During a two-year period, the employment rate among parents increased marginally, from 27 to 31 per cent. Further, the improvements in other target areas were minor. However, parents reported positive experiences of the services they received (Ipsos MORI, Reference Ipsos2019).

Hence, scholars have emphasised a need to understand how family intervention projects operate and evaluate what kinds of outcomes can be realistic in the follow-up of disadvantaged and poor families. Batty and Flint (Reference Batty and Flint2012) presented a typology of various outcomes, how they interrelate and relate to various elements within the interventions. The first group of outcomes constitute crisis management, with an aim of reducing immediate risk or harm for participating families. Examples of these outcomes are reduced risks of enforcement actions or of escalating child protection incidents. The second group of outcomes are stabilising outcomes, such as maintaining housing, school attendance or relationships with agencies or services. The third group are transformative outcomes, which Batty and Flint (Reference Batty and Flint2012) divided into soft and hard outcomes. While soft outcomes comprehend improved self-esteem, mental health or interpersonal relationships, hard outcomes include improved employment, education or reduced antisocial behaviour. Batty and Flint (Reference Batty and Flint2012) further argued that stabilising outcomes are a precondition for transformative outcomes, and that soft transformative outcomes are a precondition for hard transformative outcomes.

Some studies indicate positive effects of family intervention projects on both soft and hard outcomes. For instance, based on one family case, the qualitative study by Sen (Reference Sen2016) reported the development for one single family and showed several positive changes in soft outcomes, such as improved self-esteem and self-confidence, improved relationship between the agency and the parents and improved intra-family relations. The intervention also enhanced the families’ situation on hard outcomes, such as improved educational engagement and debt alleviation. Batty (Reference Batty2014) showed that, among young people, the family intervention improved relationships, self-responsibility and self-esteem as soft outcomes, and reduced antisocial behaviour and improved health as hard outcomes. Further, the studies by Bond-Taylor (Reference Bond-Taylor2015) and Batty (Reference Batty2014) showed that both participating families and key workers experienced the follow-up work as positive and empowering.

The Norwegian family intervention project has several similarities with the UK projects, such as having a key worker with a low caseload working with several target areas and family members and coordinating delivery of services, although there are also some differences. While the family intervention projects in the UK include behavioural aspects, such as assessments of antisocial behaviour and criminality, this is not the case in the Norwegian project, where long-term social assistance recipiency is the main criterion for participation. Furthermore, nearly 80 per cent of the families enrolled in the Norwegian family intervention project have an immigrant background (Malmberg-Heimonen et al., Reference Malmberg-Heimonen, Tøge, Rugkåsa, Fossestøl, Liodden, Bergheim, Gyüre and Buzungu2019), while this is not the case in the UK family intervention projects (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017).

The Norwegian family intervention project

The manualised HOLF model

The need for a family intervention model for low-income families was emphasised in a report written by the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Directorate in 2014, which later became an official part of the Norwegian government’s political strategy on child poverty 2015–17 (Arbeids- og velferdsdirektoratet, 2014). The report gave two main reasons for developing a family intervention model: firstly, it pointed out the need to counteract intergenerational transmission of poverty and social problems and suggested that better and more coordinated support for low-income families would contribute to social inclusion, hence reducing the risk of future poverty and social problems among children in these families. Secondly, addressing children’s needs was important in order to fulfil requirements in the Norwegian Social Services Act (Sosialtjenesteloven, 2009, §1), which states that children and families should receive comprehensive and coordinated welfare services and that they need to be acknowledged in all decisions within social and welfare services. The development of a manualised family intervention model was also in accordance with the national strategy for labour and welfare services that emphasised the development of effective tools and models in the follow-up of service users (NAV, 2013). The government decided that the Labour and Welfare Directorate should be responsible for the development of the HOLF model and that its effectiveness should be independently assessed by researchers, preferably in a randomised design.

Prior to the onset of the study, the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Directorate commissioned a literature review of comprehensive family interventions in the UK and the Nordic countries (Fløtten and Grødem, Reference Fløtten and Grødem2014). A central conclusion from this literature review was that there is little knowledge regarding the effectiveness of family interventions. While the UK studies provided some insight, the Nordic studies were mainly local and small in scale. Based on the results from the review, the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Directorate decided that no existing family intervention model identified in the literature review was transferrable as such, but that there was a need to develop a family intervention model suitable for Norwegian welfare structures – that is, the HOLF model. The HOLF model was thoroughly developed, with manuals, tools, schemes and supervision structures being piloted in the practice field prior to implementation (Malmberg-Heimonen et al., Reference Malmberg-Heimonen, Tøge and Fossestøl2018). Central for the development of the HOLF model was also the Labour and Welfare Directorates’ experience from previous development projects and knowledge of various empirically supported tools and methods, such as motivational interviewing and appreciative inquiry (Malmberg-Heimonen et al., Reference Malmberg-Heimonen, Tøge and Fossestøl2018).

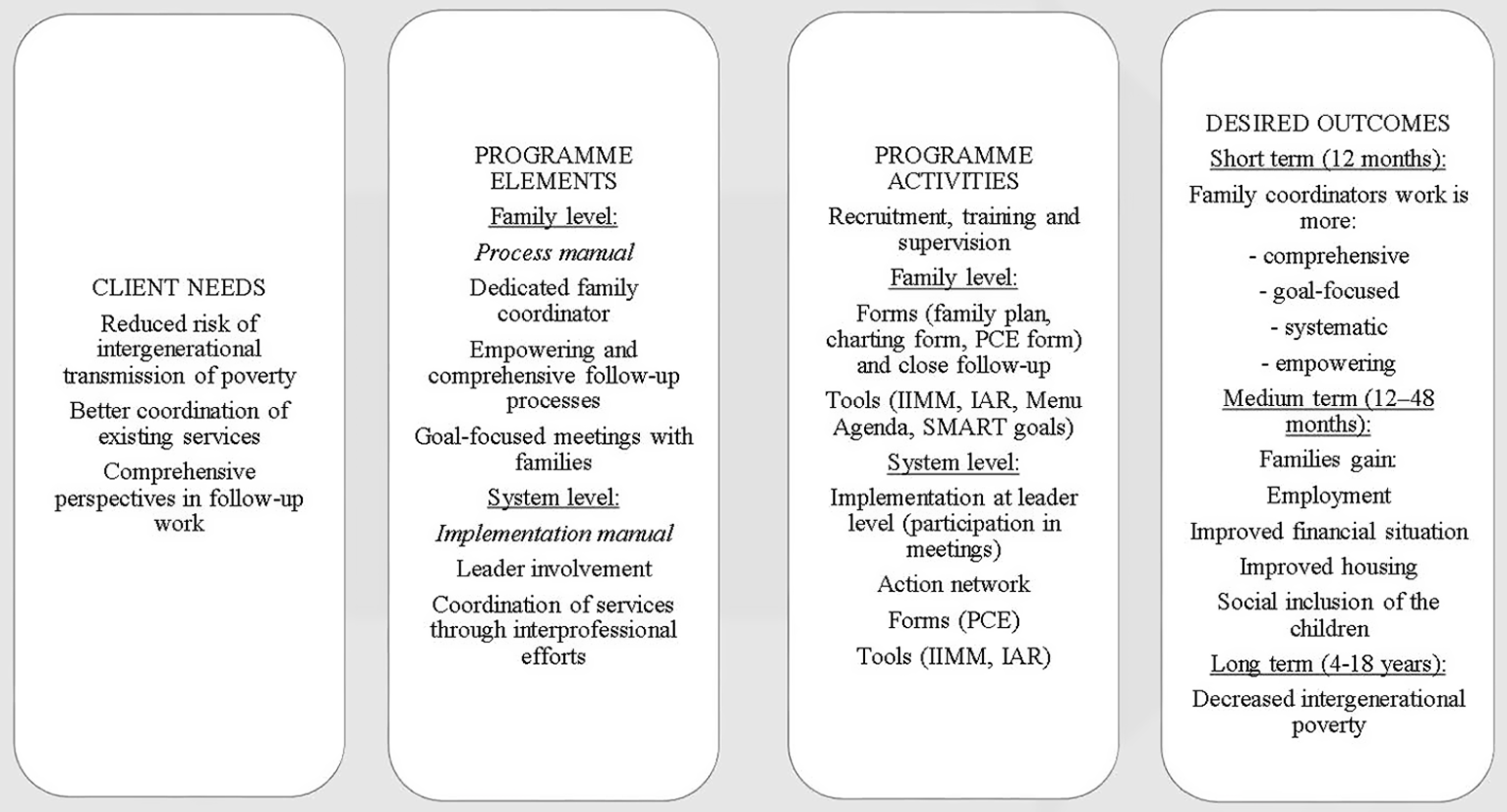

Figure 1 demonstrates the logic model for the HOLF model – namely, client needs, programme elements, programme activities and anticipated short-, medium, and long-term outcomes (Malmberg-Heimonen et al., Reference Malmberg-Heimonen, Tøge and Fossestøl2018). The model is described in two manuals, which relate to the family level and the system level of intervention. While the HOLF Process Manual describes the work family coordinators do in their follow-up with families, the HOLF Implementation Manual describes the implementation at local offices and the coordination of services with interprofessional actors – for example, child welfare and health services.

Figure 1. A logic model for HOLF (Malmberg-Heimonen et al., Reference Malmberg-Heimonen, Tøge and Fossestøl2018).

Of the programme activities in the HOLF model, central are the forms and tools that structure and systematise the follow-up of families and collaborators as well as the supervision and follow-up by the project group from the Labour and Welfare Directorate. Follow-up by the project group at the Directorate included the follow-up of office leaders, six seminars for office leaders and family coordinators, case-based supervision of family coordinators in a train-the-trainer model and feedback whenever needed (e.g. questions related to the follow-up of families or the roles of office leaders or collaborators). Each target area was treated at a seminar, in which research was presented and family coordinators and leaders could discuss problems across offices. Further, the case-based supervision for family coordinators involved regular reporting and discussions to resolve any problems family coordinators experienced in their follow-up work with families.

The forms of the HOLF model are used to chart the situation of the family in all target areas, to achieve more goal-focused meetings with families and to plan the tasks the family and family coordinator should do between meetings. The Charting form is used to chart the family’s situation in the four target areas, while the Family Plan is a form for planning the follow-up activities within the four target areas. The form for Preparation, Conduct and Evaluation (PCE) is used by family coordinators to prepare for meetings with families, leaders and collaborating actors (schools, health services, child welfare services) and to evaluate the meetings.

There are also tools that family coordinators should apply in meetings with families and collaborators. IIMM (Inform, Involve, Mobilise, and Make responsible) is a tool for informing and involving the family and collaborators and making them responsible for reaching their goals. The Menu Agenda is a tool that family coordinators use in meetings with the family, with a view to acknowledging each family’s wishes and needs. The family and family coordinator fill in important themes to work with, discuss them, and collectively agree on and prioritise themes for the specific meeting. IAR is a tool for Investigating, Adding information and Re-investigating. The family coordinator makes inquiries into the information needs of the family and communicates this information to the family; thereafter, the family coordinator investigates whether the family has understood the given information. SMART goals is another tool; it emphasises that goals set with the family should be Strategic and specific, Measurable, Attainable, Results-based, and Time-bound.

According to the logic model (Figure 1), the expectation is that the programme elements and activities of the HOLF model will lead to a more comprehensive, goal-focused, systematic and empowering follow-up of families, which in turn will improve the families’ situation in the four target areas of parental employment, financial situation, quality of housing and children’s social inclusion. In a long-term perspective, the HOLF model will contribute to reduced intergenerational poverty (Malmberg-Heimonen et al., Reference Malmberg-Heimonen, Tøge and Fossestøl2018).

Data and methods

Study design

The Norwegian Labour and Welfare Directorate commissioned an independent study of the HOLF model’s effectiveness. The study that was conducted between 2016 and 2019 used a cluster-randomised design with twenty-nine participating Labour and Welfare offices (NAV offices). We have previously described data procedures and methods in the research protocol more extensively, but give a shorter description here. The research protocol for the cluster-randomised study has been registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (Identifier: NCT03102775), and the research protocol has been published (Malmberg-Heimonen et al., Reference Malmberg-Heimonen, Tøge, Gyüre, Rugkåsa, Fossestøl, Bergheim and Liodden2017). The Norwegian Centre for Research Data granted ethical permissions for the study (case no. 47483) in addition to permissions from the Norwegian Data Protection Authority (case no. 48510) and the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Directorate (case no. 16/2598). It is important to stress that all participants gave their consent to participate and could withdraw from the study at any time and for any reason. The researchers are bound by professional confidentiality related to all data and analyses, and we will ensure that participants are not identifiable in any publications or disseminations.

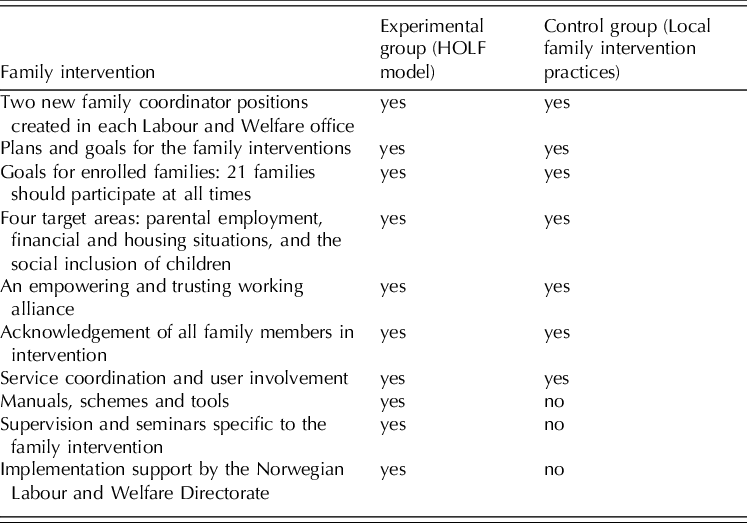

We randomised twenty-nine NAV offices into experimental (fifteen offices) and control groups (fourteen offices). Table 1 shows the main difference between the governmental HOLF model (experimental group offices) and local family intervention practices (control group offices). The experimental group offices implemented the HOLF model, including manuals, schemes and tools as well as supervision and seminars to structure the follow-up of families. Experimental group offices also received implementation support from a resource group at the Labour and Welfare Directorate. However, there were also several similarities between the groups, as all participating offices received two family coordinators, had plans and goals for the family interventions and a relatively low caseload of twenty-one families. In both groups family coordinators also addressed the four target areas and followed up all family members, aiming for an empowering and trusting working alliance. Further, they had an emphasis on service coordination and user involvement. If a family left the project, the family coordinator invited a new family to receive the intervention.

Table 1 Main differences between experimental and control group offices in the cluster-randomised study

Source. Malmberg-Heimonen and Tøge (2020)

Prior to randomisation of the offices, all offices identified their target group of families according to specific inclusion criteria. The criteria were reliance on social assistance as a main source of income or in addition to other types of welfare support for at least six (or threeFootnote 1 ) of the last twelve months, and having up to four children under the age of sixteen years. Families were excluded from the target population if:

-

1. They were participating in other comprehensive family interventions,

-

2. One or both parents were undergoing treatment because of heavy substance abuse and/or serious mental disorders, or

-

3. The child or children were temporarily placed in child welfare institutions or living with relatives or other caregivers or the family was under investigation by child welfare authorities, due to suspected child neglect or because a placement with new caregivers was in process.

After these procedures, the office leaders and family coordinators created a family list including 3033 families covered by the twenty-nine participating offices, from which family coordinators drew families to be invited to the family intervention projects. In total, the family coordinators initially drew 1597 families from the lists and offered them follow-up. The thirty family coordinators applying the HOLF model (in the fifteen experimental offices) drew 828 families, while the twenty-eight family coordinators who applied local family intervention practices (in the fourteen control offices) drew 769 families. All participating coordinators, independent of whether they were applying the HOLF model or not, followed the same procedures when recruiting families.

Participation in the family intervention was voluntary. When the families agreed to participate, they gave their written consent to participate in the study, agreed that the study could use administrative data (including employment status) and were asked to respond to a baseline questionnaire. In the experimental offices, 394 families (535 parents) agreed to participate. In the control offices, 375 families (520 parents) agreed to participate. The administrative data cover all 1055 parents, while 862 parents responded to the baseline questionnaire (442 in the experimental group and 420 in the control group). From administrative data we see that families were more likely to decline where, at the time they were offered follow-up by a family coordinator, at least one of the parents was employed. We repeated the questionnaire twelve months after the baseline questionnaire. This study design enabled us to compare outcomes – for families who were followed up by family coordinators applying the HOLF model, compared to families who were followed up by family coordinators developing local family intervention practices.

Measures

The four target areas of the family intervention projects were assessed at baseline and twelve months after the baseline questionnaire.

The first target area of the family interventions was to improve parental employment. Parental employment was assessed by a dichotomous variable where parents are defined as ‘employed’ (‘1’) if they reported work as their main activity in the follow-up questionnaire, or if the State Register of Employers and Employees had reported to the Directorate (NAV Registry Management, 2019) that parents had been working at least eight hours during the week occurring twelve months after the baseline questionnaire. The rest of the parents were coded as ‘0’.

The second target area of the family intervention was to enhance the financial situation of the family. The families’ financial situation was assessed by one single question: How is your or your family’s financial situation at the moment? The response options were very poor (1), poor (2), neither poor nor good (3), good (4) and very good (5).

The third target area of the family intervention was to improve the quality of housing. Quality of housing was measured through five items capturing various dimensions of housing quality:

It is safe in the immediate vicinity of the housing

There are nice outdoor areas and parks in the immediate vicinity of the housing

Nice people live in the immediate vicinity of the housing

I am happy with the size of the housing

I am happy with the standard of the housing

Parents were asked to assess how satisfied they were with the various housing dimensions, and the response options were not at all (1), to a small extent (2), to some extent (3), to a great extent (4) and to a very great extent (5). A scale measuring the quality of housing was coded by means of observed values on the five items. At baseline, the items of the scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.767.

The fourth target area of the family intervention was to improve children’s social inclusion. Regarding the assessment of children’s social inclusion, their participation and involvement in the society was emphasised (UN, 2016). We measured children’s social inclusion through three questions on whether the oldest child has the opportunity to:

Participate in organised leisure activities

Have hobbies

Go to events (e.g. concerts, festivals, circuses)

The response options were yes (1), cannot afford (0) or do not need (0). A sum variable, assessing children’s social inclusion, was coded as means of observed values on the three items, where each of the items had values from 0 to 1. To be able to compare responses between baseline and the follow-up questionnaire twelve months later, we asked parents to evaluate their oldest child.

Background measures were assessed through year of birth, number of children, whether they were single parents, whether they were born in Norway or had immigrated, and if immigrated, the duration in years since their arrival. All background variables were drawn from the Norwegian Basic Data Register for Personal Information (TPS), which means we had complete information at baseline, independent of whether the parents responded to the baseline questionnaire or not. Through the baseline questionnaire, we additionally included information on the number of meetings with staff at NAV offices (0–10) the month prior to the questionnaire and whether parents had vocational or higher education (0) or primary school or lower education (1). Further, we assessed parents’ self-reported health with the response options of very poor (1), poor (1), neither good nor poor (0), good (0) and very good (0).

Statistical analyses

To analyse changes between baseline and follow-up (T2), we report means and p-values for parental employment, financial situation, housing quality and the social inclusion of children in experimental and control groups. To analyse the effectiveness of family coordinators implementing the HOLF model relative to family coordinators implementing local practices, we applied two-level regression models adjusted for the nested structure of the data, baseline outcome measures and randomisation bias. All analyses were conducted in Stata/MP 16.1. For parental employment, which is a binary outcome, we used a logistic regression model (melogit command), while for the remaining outcomes we used linear regression models (mixed command). For parental employment, the effect sizes are reported as odds ratio (OR), while for the remaining outcomes, effect sizes are reported as Cohen’s d (calculated as coefficient divided by the pooled standard deviation at T2). The syntax for the analyses is available upon request.

Success of randomisation

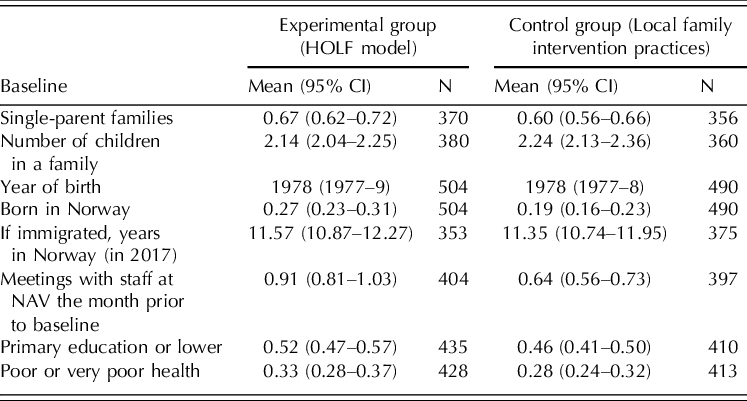

Table 2 shows characteristics for families from experimental and control group offices, at baseline before the families were recruited to the intervention. In the experimental group 67 per cent of all households were single-parent households. In the control group the share of single parents was 60 per cent, however, with no significant difference between experimental and control groups (p = 0.056). The number of children per family was 2.14 in the experimental group and 2.24 in the control group, with no significant difference between the groups (p = 0.199). In both experimental and control groups, the average year of birth among the parents was 1978 (p = 0.655). However, parents from experimental group offices were more often born in Norway compared to parents from control group offices (27 per cent vs. 19 per cent, p = 0.004). Among parents who had immigrated, the duration since immigration was beyond eleven years (11.57 years vs. 11.35 years, p = 0.635). Prior to the intervention, parents from the experimental group had had more frequent meetings with staff at NAV offices than parents from control group offices (0.91 meetings vs. 0.64 meetings, p >= 0.001). In the experimental group, 52 per cent of parents had primary school or lower education as their highest attained education. In the control group this share was 46 per cent (p = 0.065). In the experimental group, 33 per cent of parents reported having poor or very poor health. In the control group the share was 28 per cent (p = 0.146).

Table 2 Parents’ characteristics in experimental (HOLF model) and control groups (local family intervention practices) at baseline

Table 3 shows the baseline values for the four target areas; none of them showed significant differences between parents from the experimental and the control group offices. In final regressions we controlled for the baseline differences found between the two groups – that is, having parents born in Norway and the number of meetings with staff at NAV a month prior to the baseline.

Results

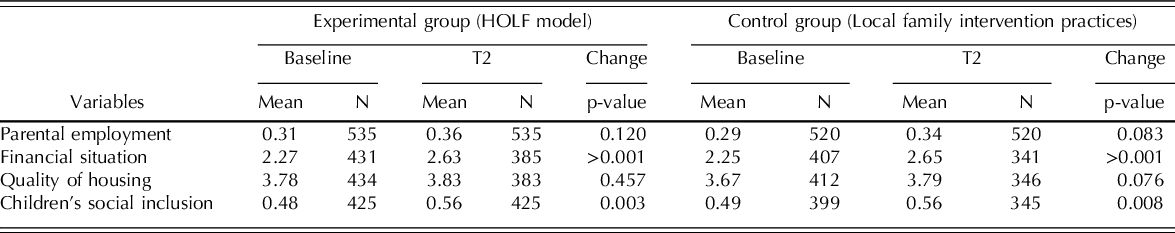

Regarding the four target areas of intervention, Table 3 shows the means for baseline and T2, and the p-values for changes between baseline and T2. At baseline, 31 per cent of parents within the experimental group offices were employed, which had increased to 36 per cent at T2. Although positive, the change was non-significant. The equivalent figures for parents within control group offices were 29 per cent at baseline and 34 per cent at T2, also with a non-significant change. For parents in both groups the financial situation had improved significantly, the change being from 2.27 at baseline to 2.63 at T2 for parents from experimental group offices and from 2.25 to 2.65 for parents from control group offices. This means on average a change from a ‘poor’ financial situation towards a financial situation that is ‘neither poor nor good’. There was a slight improvement for the quality of housing, measuring from 3.78 at baseline to 3.83 at T2 for parents within experimental group offices and from 3.67 to 3.79 for parents within control group offices. Even at baseline parents were rather satisfied with their housing quality, with evaluations on average close to four (‘to a great extent satisfied’). For the target area of social inclusion of children, parents in both groups evaluated the situation significantly more positively at T2 than at baseline. For parents from experimental group offices this change was from 0.48 at baseline to 0.56 at T2, while for parents from control group offices the change was from 0.49 to 0.56. This means that children had on average access to 48 and 49 per cent, respectively, of the arenas of social inclusion at baseline, while at T2 this percentage had increased to 56 in both groups. Nevertheless, the results show that the changes from baseline to T2 for all target areas were similar for parents from experimental and control group offices, thus indicating minor effects of the HOLF model when compared to local family intervention practices.

Table 3 Means, number of observations (N) and p-values for change for baseline and T2 in the four target areas separately for parents within the experimental and the control groups

Note. Parental employment was a dichotomous measure of 1 = employed and 0 = not employed; Financial situation was measured by 1 = very poor, 2 = poor, 3 = neither poor nor good, 4 = good and 5 = very good; Quality of housing was assessed trough five items with response options of 1 = not at all, 2 = to a small extent, 3 = to some extent, 4 = to a great extent and 5 = to a very great extent; Children’s social inclusion was measured by two items with response options of 1 = yes, 0 = cannot afford or 0 = do not need.

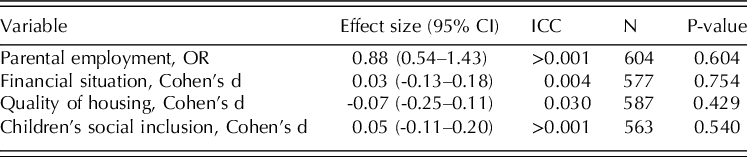

The final results of the study are displayed in Table 4, which shows the effects of family coordinators using the HOLF model, relative to family coordinators who developed local family intervention practices. To assess these effects, we carried out two-level regression analyses for each outcome, where we controlled for the baseline predictor, whether the parent is born in Norway and the number of meetings with staff at NAV offices the parent had prior to the intervention. The results are in line with the descriptive statistics in Table 3 – that is, very small and no significant effects of family coordinators using the HOLF model relative to family coordinators using local family intervention practices on all four target areas: parental employment, the financial situation, the quality of housing and the social inclusion of the children.

Table 4 Two-level regression models (individuals nested within 29 offices) estimating effects for families of the HOLF model relative to local family intervention practices

Notes. The analyses control for baseline predictor, whether the parent is born in Norway, the number of meetings with staff at NAV offices and the nested structure the data; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence intervals; ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient; effect sizes show the effectiveness of the HOLF model relative to local family intervention practices.

Discussion

In this study we compared the implementation of the manualised HOLF model, with local family intervention practices, on four target areas of intervention: parental employment, the financial and housing situations of the families, and the social inclusion of children. We assumed that the manualised HOLF model would produce more favourable outcomes than family coordinators implementing local family intervention practices (Malmberg-Heimonen et al., Reference Malmberg-Heimonen, Tøge and Fossestøl2018; Malmberg-Heimonen et al., Reference Malmberg-Heimonen, Tøge, Rugkåsa and Bergheim2021). The main finding is, however, that there was a favourable and significant development for families on two out of four target areas over the twelve-month study period, but no difference between the HOLF model and local family intervention practices. As a consequence, our expectation was not achieved – that the HOLF model (with its manuals, tools, schemes and supervision) would produce more positive effects compared to local family intervention practices.

The similar results for the HOLF model and local family intervention practices may be interpreted as meaning that it was the elements common to both intervention groups, rather than the manuals, forms and tools of the HOLF model, that may have contributed to the families’ favourable development. Elements common to both groups were, for instance, that the families had a family coordinator with a low caseload, that all family members were followed up in several target areas and that the family coordinators aimed to achieve an empowering and trusting working alliance with the families. The result is important, as studies have demonstrated that empowering and trusting support from key workers in family interventions is essential (Batty and Flint, Reference Batty and Flint2012; Bond-Taylor, Reference Bond-Taylor2015; Gyüre et al., Reference Gyüre, Tøge and Malmberg-Heimonen2020). Also important to note is that scholars such as Galinsky et al. (Reference Galinsky, Fraser, Day and Richman2013) have argued that a manual in itself is neither effective nor ineffective. While Galinsky et al. (Reference Galinsky, Fraser, Day and Richman2013) pinpointed the practice fit of interventions, the lack of favourable effects of the HOLF model relative to local family intervention practices can be interpreted as suggesting that the family coordinators already had the needed local competence regarding the target group and were thereby able to develop family interventions that fitted the practices. Hence, the key contribution of this study is that family intervention projects should ensure competent and motivated family coordinators with sufficient resources and a low caseload, while additional standardisation through manuals, schemes and tools seems to be of less importance. Amongst other, Martinell Barfoed (Reference Martinell Barfoed2018) and Skillmark and Oscarsson (Reference Skillmark and Oscarsson2020) have shown that a standardised interaction through manuals and forms can be problematic in a social work context.

Having multiple target areas is a key element of family intervention projects and in this study four target areas were assessed. Of them, parental employment is seen by policymakers as the most important factor in reducing poverty among children and families (Frazer and Marlier, Reference Frazer and Marlier2017). In this study, the portion of parents employed changed from 31 to 36 per cent in the experimental group and from 29 to 34 per cent in the control group, demonstrating a favourable but non-significant development for parents. Also the UK study of the Troubled Families Initiative showed similar results, where the employment rate, in a two-year period, increased modestly from 27 to 31 per cent (Ipsos MORI, 2019). Closely connected to employment is the financial situation of the families, where parents reported a significantly better situation at T2 than baseline, but with no difference between the HOLF model or local family intervention practices.

Another key component of family intervention projects is the whole family approach including the involvement of children. Studies have demonstrated that the involvement of children is associated with well-matched protection and care, while the opposite is the case if children are not involved (Heimer et al., Reference Heimer, Näsman and Palme2018; Malmberg-Heimonen et al., Reference Malmberg-Heimonen, Tøge, Rugkåsa and Bergheim2021). The results of this study showed a positive and significant development on children’s social inclusion over the twelve-month follow-up period, but independent of whether family coordinators used the HOLF model or local family intervention practices.

Regarding housing quality, there was only a slight increase in parents’ assessment during the one-year follow-up period. In their typology for family intervention projects, Batty and Flint (Reference Batty and Flint2012) define maintaining housing quality as one of the stabilising outcomes, meaning a stable housing situation is a goal in itself. As this study indicates that parents were already quite satisfied with their housing situation at baseline, especially with the area they lived in (figures not shown), one might interpret the findings as families already having a relatively stable and good housing situation. It is still important to note that statistics from Norway demonstrate that immigrants, single parents and large families are groups that are disadvantaged in the housing market (Thorsen, Reference Thorsen2017), and that a disadvantaged position in the housing market might have adverse consequences for the children, such as poorer school results (von Simson and Umblijs, Reference von Simson and Umblijs2021).

The study has some limitations that are important to acknowledge. Firstly, as families were not randomised to receive a family coordinator or not, we cannot be certain whether the favourable changes for families were due to the elements present in both the experimental and the control groups, or if the favourable changes would have occurred anyway in the families’ lives. Secondly, we assessed most of the target areas through self-reported questionnaire data. When interpreting the results of this study, it is therefore important to acknowledge that self-reported data can be biased – for instance, if respondents answer in ways they think are socially acceptable. However, if there are biases related to self-reported data, we expect them to be similar in experimental and control groups. Thirdly, it can be discussed whether and how well the various indicators used in this study covered the target areas. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that there were favourable and significant changes for the families regarding two out of four target areas, but no difference between those with a family coordinator using the HOLF model and those with a family coordinator who used local family intervention practices. The results indicate that the indicators were sufficient to measure the change over time for families, but that the governmental HOLF model did not demonstrate the expected greater effectiveness in spite of its efforts to structure and systematise the family intervention. Fourthly, there is also a risk that our respondents misunderstood questions due to limited language skills. Although the project covered language-interpreting services when conducting the questionnaires and in the follow-up of families, the family coordinators did not always convey this offer to participating parents, and when they did, the qualifications of the interpreters varied. Finally, it was parents who evaluated the social inclusion of the children. Involving children themselves in the study would have been preferable, although more complicated from an ethical point of view.

To sum up, this study shows no difference in the outcomes for families, regardless of whether the family coordinator implemented the manualised HOLF model or local family intervention practices; however, over the twelve-month period of the study, the families’ situation significantly improved in two out of four target areas. In light of these findings there is a need to further investigate how the HOLF model was implemented, identify conditions that may have limited the implementation and to study key elements of family interventions, especially the importance of the family coordinator role in helping low-income families.

Acknowledgements

The Norwegian Labour and Welfare Directorate funded the research project.