Introduction

On 30 March 2007, Portugal subscribed to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), the very first day it opened for signature at the headquarters of the United Nations in New York, and ratified the treaty just two years later, in 2009. At the time, the country was not yet experiencing the consequences of the global crisis that hit financial markets in 2008. A series of policy reforms embracing a new understanding of disability as a human rights issue were already in motion: in particular, the First Action Plan for the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities and Impairments (PAIPDI, 2006–9) and the National Accessibility Plan, 2006–15, deemed key political instruments for the elimination of disability-based discrimination and the removal of obstacles to the full participation of Portuguese with disabilities in the labour market and society at large. The country seemed to be on a good track to make rights become reality.

Yet just two years later, in 2011, Portugal faced a debt crisis and was placed under a strict austerity plan, with devastating and far-reaching consequences. Under all the turbulence that characterised this last decade, what was the impact of the CRPD at domestic level? At the policy level, what has changed, what has remained the same and what has deteriorated? And how has the disability movement responded to and resisted the crisis?

Using a political economy lens, this article addresses these critical questions and discusses the significance of international human rights law in shaping policy frameworks and societal practices on disability at national level. Portugal, at this regard, is a particularly interesting case study, as it has endured a harsh economic and financial crisis in which priorities of fiscal restraint competed with human rights goals. Assessing how governments tackle their international human rights commitments, in such a context, may thus illuminate the complex interplay of international human rights law, domestic policy and local politics in contemporary societies.

This article sets out to examine these issues. It starts by providing an overview of disability policy and law policy reforms introduced in Portugal around the turn of the 21st century. Then it goes on to assess the impact of the financial and economic crisis and of the austerity measures on disability rights implementation, particularly from 2011 to 2014. Finally, it concludes with reflections on the role that emerging coalitions may play in advancing disability rights in Portugal.

Methodological approach

Broadly defined, political economy can be understood as the analysis of the interplay of law, economics, and politics; or, in other words, of the relationships of State, market, and society and its impact on shaping our daily lives (Armstrong and Connelly, Reference Armstrong and Connelly1999). The recognition of contradictory, reinforcing and interpenetrating relations between the political, the economic and the social realms is central to the method of political economy and allows for multiple levels of analysis (Clement and Vosko, Reference Clement and Vosko2003).

With its roots in liberalism and Marxism, political economy understands politics and economics as integrally related and shaped by the mode of production. In Portugal today, the dominant mode of production is a particular form of capitalism. Despite their variety, the logic of capitalist modes of production is the drive for profit and this has historically contributed to the exclusion of persons with disabilities from work processes and their social segregation (Oliver, Reference Oliver1990), thus running against the recognition of their human rights.

The political economy approach also includes an analysis of the ideological and cultural, both in terms of the ideas and discourses that dominate, as in terms of those that subvert existing relations of ruling. From 2011 to 2014 the political discourse in Portugal was overtly dominated by austerity, which became ‘a powerful organizing concept’ that defined and shaped the welfare state. This had critical consequences to the state ability to advance a disability rights agenda. More recently, the political turn brought about by the 2015 legislative election seems to have displaced the hegemonic position of austerity as a ‘policy panacea’; yet, as Farnsworth and Irving (Reference Farnsworth, Irving, Farnsworth and Irving2015: 12) remind us, ‘austerity may well exist even where it does not speak its name’.

In this article, we use a political economy lens to analyse data gathered through a number of studies, conducted between 2012 and 2016, combining policy analysis with analysis of secondary data and personal stories collected through semi-structured interviews with persons with disabilities and other stakeholders in the disability field.

The first study (Pinto and Teixeira, Reference Pinto and Teixeira2012a) involved 28 interviews, conducted in 2011, with men and women with disabilities aged 18 and over. All types of impairment were represented in this convenience sample, gathered in three locations of the country, and controlled along the three independent variables considered more relevant to this investigation – sex, age group and type of impairment. This research assessed barriers to the exercise of rights by adults with different types of disability.

The second study (Pinto et al., Reference Pinto, Cunha, Cardim, Amaro, Veiga and Teixeira2014) involved 60 interviews with persons with disabilities, aged 12 and over. Although a convenience sample was used, in order to ensure diversity and balance, the sample was controlled for sex, age group and type of disability. As the first one, this study included semi-structured interviews, but also entailed a thorough collection and analysis of law and policy and the study of social representations of disability through the gathering and examination of all the disability-related stories published over the last five years on the three major media outlets in the country.

The third study (Pinto and Teixeira, Reference Pinto and Teixeira2012b) is the Portuguese component of a larger research, undertaken by the European Foundations Center, on the impact of the governments’ austerity plans on the rights of persons with disabilities in six European countries: Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and the UK (Hauben et al., Reference Hauben, Coucheir, Spooren, McAnaney and Delfosse2012). Following a common template, representatives in each country conducted desk-based research of law, policy and statistics, and semi-structured interviews designed to capture the views of local authorities or funding agencies, representative organisations of people with disabilities and services providers. In Portugal, six interviews with official authorities, service providers and disability organisations (two of each category), were conducted in the summer of 2012. Finally, we draw from statistical data compiled and analysed in the 2016 report developed for ANED, the Academic Network of European Disability experts.

All these data are gathered and combined here to enable an outline of the major developments in legal and policy framework around disability in Portugal and a discussion of the gaps found between rights in theory and in reality.

A brief overview of laws and policies on disability in Portugal

Over the turn of the century, at least at the discursive level, disability laws and policies in Portugal have undergone a dramatic shift from a medical to a rights-based model, to the point of becoming described as progressive and rights-oriented (Redruello and Ribeiro, Reference Redruello and Ribeiro2010; Simeonsson et al., Reference Simeonsson, Ferreira, Maia, Pinheiro, Tavares and Alves2010). This change, that began in the nineties and early years of the 21st century, converged with the broader international disability rights turn which had produced the celebration of the UN Decade of Disabled Persons in 1983–1992, the publication of several UN instruments, and culminated with the adoption of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) in 2006.

In Portugal, the adoption of legislation endorsing a perspective of equality and mainstreaming of people with disabilities started in 1991, when legislation promoting the inclusion of children with disabilities in ordinary schoolsFootnote 1 was first issued, followed five years later by another decree-law aiming at the removal of all architectural barriers in the public built environment by 2004Footnote 2 . Although never duly enforced, this legislation represented an important turning point in the Portuguese legal landscape for it introduced for the first time a ‘universalistic approach’ (Winance et al., Reference Winance, Ville and Ravaud2007) to disability policy, through its recognition of the role that environmental barriers play in creating disability and the need of making the environment accessible for all, and not just for people with disabilities.

In 2001 a quota law in the public administration sector was introducedFootnote 3 and in 2004, the fundamental law on disabilityFootnote 4 was updated. This bill was intended to break away with the old medical approach, advancing a new understanding that recognised disability as the result of the ‘interaction of individual and environmental factors’. Thus, rather than providing for the cure or treatment of impairments, the act aimed to guarantee the rights of people with disabilities to employment and vocational training, education and culture, social security, health, housing, sports, and recreation. Furthermore, the voice of disabled people was sought in all policy decision-making processes affecting their lives.

In 2004, through the transposition of the EU Employment Directive to national legislationFootnote 5 another important rights-based piece was enacted – the principle of non-discrimination in employment, in regards to recruitment and selection processes, access to vocational orientation and training, wages and career development and participation in collective bargaining structures. And in 2006, following a Recommendation of the Council of Europe, Portugal issued its first Plan of Action for the Integration of Persons with Disabilities and Impairments 2006–09 (PAIPDI). In the Plan, disability was defined as a ‘human rights issue’ with the document devoting a large number of pages to describe this new approach and its policy implications (for a detailed analysis of the PAIPDI, see Pinto, Reference Pinto2011). In the same year, a new law prohibiting discrimination on the basis of disabilityFootnote 6 was passed. Applying both to the public and the private sectors, the bill covers access to goods and services, housing and the built environment, healthcare, education, and employment. One year later, a National Accessibility Plan Footnote 7 (PNPA) was adopted. Recognising that, despite former legislation, huge gaps in accessibility persisted in the Portuguese society, the PNPA was introduced as a tool to fight the ‘discrimination and exclusion’ experienced by persons with disabilities and the elderly. Covering the period 2007–15, the Plan established a set of measures to remove barriers to accessibility in transportation and the built environment, in the workplace, housing and information technologies.

In the service provision sector, reforms were also introduced with the establishment of the National Early Intervention SystemFootnote 8 (SNIPI) in 2009. SNIPI was said to embody the ‘principles enacted in the CRPD’ and contribute to ensuring ‘the rights of all children to participation and social inclusion’ (Preamble).

The education sector had another breakthrough in 2008, when the government introduced legislationFootnote 9 forcing the closure of special schools and prohibiting discrimination of children with disabilities in public and private schools funded by the Ministry of Education. The schools were obliged to recognise the unique needs of these students and set up Individual Education Plans to provide them an education adjusted to their needs.

In December 2010, following the first Disability Action Plan, a new National Disability Strategy (ENDEF) was adoptedFootnote 10 for the years 2010–2013. The paper alluded to the ratification of the Convention to reaffirm the commitment of the Portuguese State to ‘promoting, protecting and ensuring a life with dignity for persons with disabilities (. . .) fight discrimination and improve the quality of life of persons with disabilities and their families’. Disability mainstreaming in society, and at all levels and areas of government, as stated in article 4c of the CRPD, was clearly embraced in this document.

Organised along four axes – Multi-discrimination, Justice and Access to Rights, Autonomy and Quality of Life, Accessibility and Administrative Organization – the Strategy suggested a more holistic rights-based approach to disability than the former Action Plan. More importantly, the ENDEF included a measure concerned with setting up ‘the first pilot project of personal assistance (PA)’, a scheme long due in Portugal and clearly aligned with the rights based approach of the CRPD.

In sum, around the turn of the century, under the influence of supranational entities (such as the EU) and international Conventions, particularly the CRPD (Kelemen and Vanhala, Reference Kelemen and Vanhala2010), new legal and policy frameworks introduced in Portugal, came to largely represent disability as a matter of rights, not welfare. This rhetorical shift was beginning to be accompanied by a deeper move drifting away from mostly charity-based, medically focused and segregated policy responses to disability, into the provision of mainstreamed services and supports, enabling the social participation of persons with disabilities, in the context of a more accessible and inclusive Portuguese society. However, the paradigm shift to a rights-based model and ‘universalist approach’ (Winance et al., Reference Winance, Ville and Ravaud2007) remained incomplete. As Baudot and colleagues (Reference Baudot, Borelle and Revillard2013a) remind us ‘‘models’ are never found in their pure state in empirical reality’ (p.118, my translation). So while rights were being promoted, and a social rather than medical view of disability disseminated, measures and processes characteristic of the individual-medical approach persisted as elsewhere (Baudot et al., Reference Baudot, Duvoux, Lejeune, Perrier and Revillard2013b); and entitlement to most social rights, whether supports to inclusive education, benefits or social care services continued to be based on medical diagnosis, denoting the persistence of the more traditional ‘category-based model’ (Winance et al., Reference Winance, Ville and Ravaud2007). More generally, due to low levels of awareness of disability rights in Portuguese society, lack of enforcement of accessibility legislation and persisting forms of subtle and indirect discrimination, the everyday lives of many Portuguese with disabilities remained marked by inequality and exclusion. Nevertheless the role that norm diffusion had as an important drive for social change in Portugal during this period (Kelemen and Vanhala Reference Kelemen and Vanhala2010) should not be underestimated.

Crisis and austerity – what changed and for whom?

Just when the rights discourse was gaining space at the policy level, the global financial crisis hit the country. In May 2011, the Portuguese government signed a memorandum of agreement with the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. In return for the 78 billion EURO bailout, what is known as the Troika imposed an economic adjustment programme in the country that required increasing tax revenue and reducing public spending, including the reduction of more generous state pensions and the freezing of others. Cutbacks in the health sector amounted to 810 billion EUR and in the education sector to 507 billion EUR.

I do not want to suggest that without this adverse economic situation, everything related to disability rights would have been fine. There would still have been many challenges to fully implement the rights agenda but austerity regimes tend to reduce welfare benefits, cut public services and raise unemployment, and all of these affect disproportionally persons with disabilities.

The government that took office in the Summer 2011 immediately announced a Social Emergency Programme. The programme was focused on addressing the needs of the ‘most vulnerable groups’ with persons with disabilities identified among them. However, the measures proposed abided with a strict neoliberal programme, advancing a ‘work-first agenda’ (Roulstone and Rideaux, Reference Roulstone and Prideaux2012) and offering respite care services for informal carers, which presumed the continuing availability of family support arrangements, instead of promoting independent living through the most awaited PA scheme. Not unsurprisingly, the discourse of rights waned from the government rhetoric in this article.

The austerity programme lasted three years, from 2011 to 2014, but it had a profound and long lasting impact on the realisation of social and economic rights in general and, particularly, in the progressive implementation of disability rights. Areas such as inclusive education, vocational training and employment, access to health and social protection as well as the aspirations of persons with disabilities to achieve independent living were particularly affected (Pinto and Teixeira, Reference Pinto and Teixeira2012b).

In the area of education, the cuts introduced generated a lack of financial and human resources to support inclusive education. Research reported insufficiency of teachers and school staff to work with disabled children, lack of or late arrival of pedagogical materials such as books in Braille and other technical devices necessary for the education of children with disabilities, and lack of accessible transportation to attend classes (Perdigão et al., Reference Perdigão, Casas-Novas and Gaspar2014; Pinto et al., Reference Pinto, Cunha, Cardim, Amaro, Veiga and Teixeira2014). This has created barriers to education for students with disabilities as the following report, collected in one of our studies, also illustrates:

I had problems with transportation. My classes were from 6 to 8pm. The accessible bus could only drive me three days a week. On the other days, I had to rely on my parents. My mom used to drive me but to fit her work schedule I had to be at school by 1pm for a class that didn't start before 6pm. And then at 8pm, she would come to pick me up. This is how we made it work. (Francis, 29 years old, in Pinto et al., Reference Pinto, Cunha, Cardim, Amaro, Veiga and Teixeira2014)

Data from EU-SILC (2012) show that the rate of early school drop-outs is larger in Portugal among students with disabilities (35.1 per cent) than among students without disabilities (21.4 per cent). It is very likely that the inadequate staffing and insufficient provision of material resources is impacting the quality of inclusive education and compromising the future prospects of students with disabilities. Many are returning to social care institutions, once they complete compulsory education (Pinto et al., Reference Pinto, Cunha, Cardim, Amaro, Veiga and Teixeira2014).

Impacts of austerity measures on the realisation of the right to health were also experienced by persons with disabilities and their families at various levels. In addition to the introduction of user fee in healthcare services, there were new restrictions in the access to non-urgent medical transportation. Given the lack of accessible transportation in Portugal, these services have been used by many persons with disabilities to reach rehabilitation facilities and access treatments. New regulations issued in 2012 turned this into a means-tested benefit, available free only to persons with a degree of incapacity of ≥60 per cent and a household income of 419.22 EUR or less. Furthermore, access to the service became more bureaucratised and dependent upon a medical assessment and prescription. With increased conditionality imposed, many persons with disabilities were left without necessary services. JL is just one such case:

JL is a young man of 20 years old and a wheelchair user. Due to the severity of his disability he requires 24h personal attendance and, therefore (. . .) he should use the so-called ‘non-urgent medical transportation’, provided by the local fireman department. However, due to the new regulations introduced in 2012, JL was only allowed to use 120 days of this transportation service. His family doctor refused to issue a prescription asking for an extension of this service. Since the family had no other means of ensuring his transportation, JL stayed home for 6 months, unable to attend the Day Care Center (Pinto and Teixeira, Reference Pinto and Teixeira2012b).

Crisis and contradictions – the case of employment measures

In spite of the accent on the ‘work-first agenda’ (Roulstone and Rideaux, 2012), rights to vocational training, employment and work of persons with disabilities were severely affected by the austerity measures set in motion during the Troika years. Between 2011 and 2014, public expenditure on the vocational training system of persons with disabilities (which included measures of assessment, training, follow-up, self- and supported employment, and provision of assistive devices for employment) was reduced by 62 per cent, while the number of beneficiaries of these various programs increased by over 89 per cent. Therefore, less hours of training and less support became available to each trainee, sometimes with devastating consequences, as the story of Anne illustrates:

Anne started a vocational training programme to become an Administrative Assistant in January 2010. She was at the time 25 years old and had completed nine years of schooling in a mainstreamed school with an adapted curriculum. She had no previous professional experience. During the training she was able to acquire good skills in informatics and archive. In the final stage of the training she was placed in a consulting firm to complete an internship and she did 371 hours of practice, performing the tasks of archiving and support to database feeding. Her performance was always assessed as positive and she showed great initiative. However, she needed to improve the pace of her work and therefore her time spent in the company was increased from 2 to 5 days a week. Both the firm and the trainee were interested in extending the practicum but M.C was approaching the maximum number of training hours allowed (2900h). In the end, the firm did not hire M.S., because they needed more time to be sure that she would be able to improve the pace of her work as she would get more experienced in the job. (Pinto and Teixeira, Reference Pinto and Teixeira2012b)

With soaring rates of unemployment in the country, affecting particularly youth and persons with disabilities, the government introduced in 2012 a new Programme – Impulso Jovem – with several measures to promote youth employability and support small and medium size companies that hired them. One of the key pieces of this new programme – which from 2014 on came to be known as Garantia Jovem – is the provision of internships that, in the case of a person with disabilities, can last for as long as one year. Financial incentives associated with this programme are also scaled up when the youth is a person with disability. However, as there is no obligation on the part of the employers to issue a contract at the end of the internships, many employers just keep replacing one intern with another instead of creating new jobs. Matilde describes her experience in this way:

I went to work as a receptionist and I must say I was a bit insecure when I started due to my speech impairment. But fortunately all went very well. Yet, after one year, they dismissed me, although they had said before they were very satisfied with my work. Why did they dismiss me? Not because they disliked my work but because they could not receive the incentives any longer. After one year it all falls on the company. They told me: ‘We're very sorry, we liked you a lot, if only there was a way to continue like this we would keep you, but we can't and we don't have the resources to hire you’. (Matilde, 40 years old; in Pinto et al., Reference Pinto, Cunha, Cardim, Amaro, Veiga and Teixeira2014)

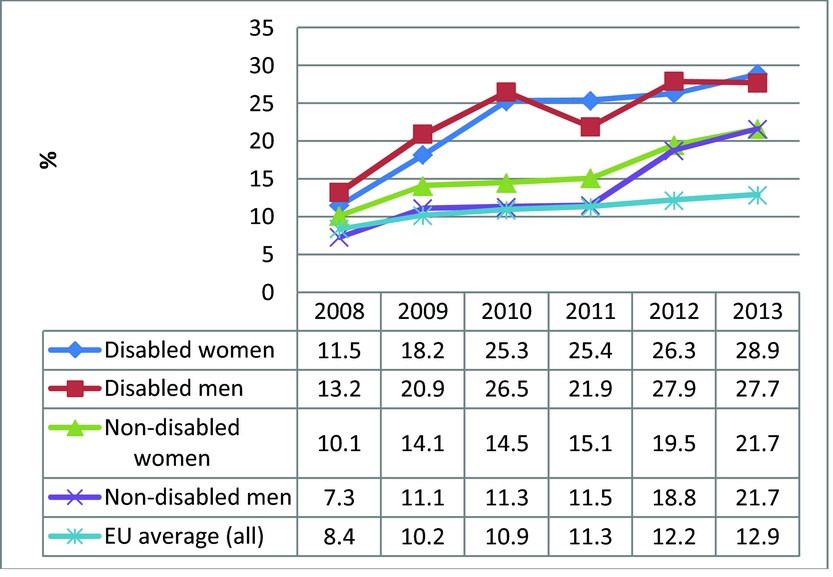

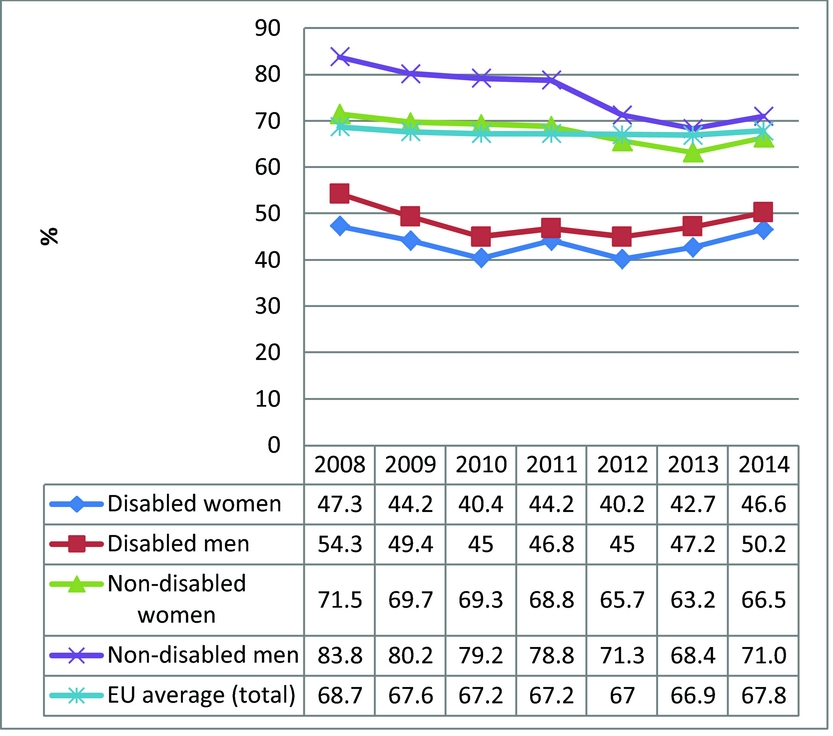

Not surprisingly then, and despite the availability of these affirmative action measures, unemployment rates for persons with disabilities continue to be higher than for the population in general, while employment rates remain lower, as data from EU-SILC show (see Figures 1 and 2). Moreover, since interns count as ‘employed’ in national statistics, their high turnover in Garantia Jovem programmes helps to explain, why there is, simultaneously, an increase in employment and unemployment rates among the population with disability over the period 2011–2014. Data from the National Institute of Vocational Training and Employment show, in fact, that while the number of persons with disabilities who benefited from measures to support job placement went up from 637 in 2011, to 2503 in 2014, the number of unemployed men and women with disabilities also increased from 10408 to 12667 over the same period.

Figure 1. Trends in unemployment by gender and disability in Portugal and EU (aged 20–64)

Figure 2. Trends in employment by gender and disability in Portugal and EU (aged 20–64)

The austerity plan further involved a hiring freeze in the public sector. The law in place since 2001 imposes a 5 per cent quota for persons with disabilities in the public sector (the 2 per cent quota in the private sector, foreseen in the law, was never regulated). Rato et al. (Reference Rato, Rando, Anjos, Alexandre and Rodrigues2008) found that by 2006 only about 3000 employees, or less than 1 per cent of all civil servants, were persons with disabilities. Of these, 80 per cent had impairments related to the diagnosis of cancer and, therefore, were probably already employed by the State when then acquired their disabilities. While the recruitment of workers with disabilities has been all along quite marginal, with the hiring freeze imposed on the Public Sector by the Troika in 2011, it is very unlikely that this situation will improve.

Independent living: waiting for Godot?

The implementation of austerity policies in Portugal not only slowed down the progress that had been made in previous years in introducing policy that advanced the rights of people with disabilities, it also suspended the provision of new rights and services that although formally announced, never actually came to life. In the play by Samuel Beckett, two characters wait for the arrival of someone named Godot who never arrives. The independent living policy and the Personal Assistance service scheme are, in this regard, reminiscent of Beckett's play. Despite being included in the Disability Strategy 2010–13 as one of its most emblematic goals, the pilot project of PA services was forgotten and never implemented.

The lack of PA schemes forces disabled persons in Portugal to turn to homecare services to get assistance with basic daily activity tasks, including self-care. As these services were designed to assist the elderly they operate on the assumption that the clients do not live productive lives, do not work nor study nor are involved in any activities outside the house. The gap, between the actual support needs of persons with disabilities in order to live independent lives and what these services are capable of providing, is clearly illustrated through the following report of one such user:

My personal hygiene tasks take some time and the homecare service starts at 8am only – exceptionally in my case, because usually it begins at 9 am, they opened an exception for me – but still, I only get to work at 11am and often at 11:30am, which causes me a lot of problems. In the evening, I do not use the service to get to bed because they often end up the service and I'm still at work. Sometimes they end up at 6pm, they put people in bed at 6, 7, 8pm (Antonio, age unknown; in Pinto and Teixeira, Reference Pinto and Teixeira2012a)

For lack of personal assistance schemes, many persons with disabilities, particularly those with intense care needs, are forced to rely on their families. Family caregivers, however, receive very few supports to undertake their care tasks, which creates an added burden on these families, increasing their economic vulnerability (Portugal, Reference Portugal, Martins and Hespanha2010) and perpetuating social representations of persons with disabilities as needy and dependent, not as citizens with rights as the Convention asserts.

In addition to the PA pilot project, roughly one quarter of all the measures proposed in the Disability Strategy 2010–2013 were never implemented. The Strategy's final evaluation report acknowledges this outcome which, it claims, is due to ‘structural and conjuncture constraints (. . .) caused by variables such as the restructuring, extinguishing and/or amalgamation of services and the overall commitment to budgetary restraint’ (INR, 2014: 8). According to the same report, the rate of non-compliance was highest in axels 3 (Autonomy and Quality of Life) and 4 (Accessibility and Design for All), incidentally the two more relevant axels, from a rights perspective, to promote social inclusion and effective participation.

Indeed, an accessible environment is a critical element to achieve independent living. Although there are no available statistics on the number of accessible public buildings and transports in Portugal, the 2006 Accessibility Law has been poorly enforced and therefore lack of accessibility remains a huge obstacle to many persons with disabilities. Rose, one of our interviewees in 2012 reported:

The healthcare centre was recently built, and I don't have access to family planning services. I don't have access to it and so I can't do some examinations. The Taxes Office is the same – it hasn't an easy access, it does from one side of the building but not from the other. (Rose, 28 years old; in Pinto and Teixeira, Reference Pinto and Teixeira2012a)

The fact that planned measures and set goals failed signals the low priority that disability rights came to bear in the political agenda during the era of austerity. Yet, perhaps even more telling is the fact that, although expired in 2013, the Disability Strategy has not yet been replaced by any other similarly comprehensive policy. In other words, five years after its expiration, there is still not a clear vision, or political will, about where and how to go in order to make real the commitment of progressively realising human rights for all Portuguese with disabilities. Portugal continues to be lagging in disability rights implementation. The vision of an inclusive society, of citizens different in abilities, yet equal in dignity and rights, is becoming little more than an empty promise.

Economic insecurity and increased risk of poverty

The slowing down in disability rights progress has been noted in a number of European countries (Hauben et al., Reference Hauben, Coucheir, Spooren, McAnaney and Delfosse2012). As the authors claim ‘when public spending cuts are at stake, sectors such as social protection (where the pension and health insurance sectors represent the most costly areas), social services, health care and education are the most likely candidates for reductions’, and persons with disability tend to be doubly affected – not just by cuts in disability-specific benefits and services, but also by general cutbacks that impact the whole population.

That is also what happened in the pension sector in Portugal. The austerity plan that followed the bailout agreement imposed a freeze on all pensions, including those disability-related and a new conditionality on access to benefits, as well as new taxation on income generated through pensions. In Portugal, disability-related benefits include a myriad of schemes involving a disability pension (for workers who retire due to disability), a disability allowance (for adults with disabilities who never worked and are considered unable to do so), a means-tested supplement to family allowances (for parents of children with disabilities) and an allowance for assistance by third-person (for children and adults with disabilities who require hygiene and other self-care) as well as a special education cash benefit for parents of children with special education needs. In the context of implementing fiscal consolidation measures, in 2010 the government changed the conditions for entitlement to all cash benefits within the national social security system. These conditions became more stringent with a new and enlarged concept of household introduced to calculate the ‘household income’ and determine the ‘level of need’ of the applicants. These changes decreased the number of beneficiaries of family allowances – from 1,399,985 in 2011 to 1,267,691 in 2014 – as well as the amounts provided. However, given that families with children with disabilities are more likely to be poor, despite the more stringent eligibility conditions, the number of families benefiting from the means-tested disability supplement to family allowances increased over the same period – from 84,042 in 2011 to 85,857 in 2014, another indicator of their precarious economic situation.

From 2011 to 2016 all cash benefits, including disability-related benefits, were frozen. Given that the level of cash provided was already low (see Table 1) and that the cost of living got higher throughout this period, the economic insecurity of persons with disabilities and their families, particularly those already more economically disadvantaged, aggravated.

Table 1. Amounts provided and number of beneficiaries by Benefit

Source: Segurança Social, Estatísticas da Segurança Social, accessed at http://www4.seg-social.pt/estatisticas on 3 August 2017

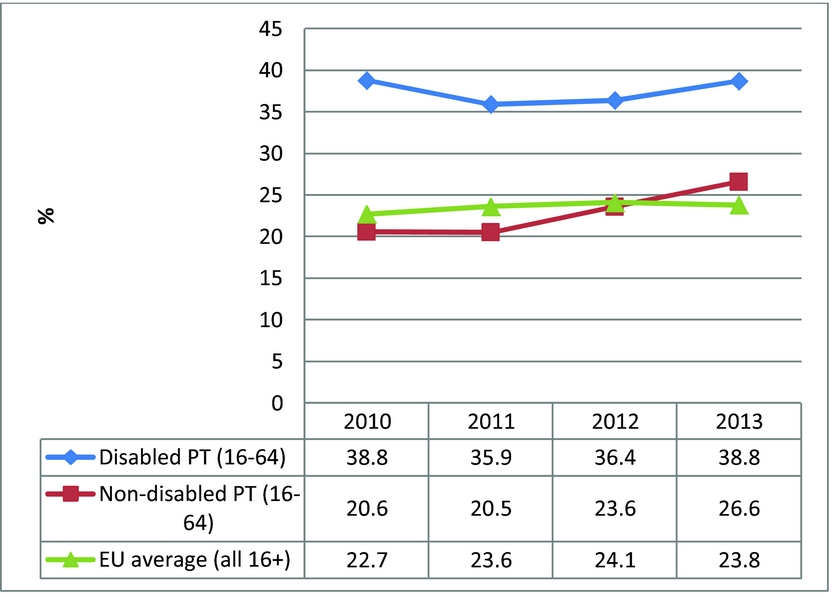

Research (Portugal, Reference Portugal, Martins and Hespanha2010) shows that, despite the low amounts involved, disability-pensions and allowances are the main source of income to persons with disabilities and their families. Not surprisingly then, as recent data from the Eurostat demonstrate (EUSILC, UDB 2013 – version 2 of August 2015 compiled by ANED 2016), the risk of poverty and exclusion among persons with disabilities in Portugal increased during the austerity years and in 2013 was 12 p.p. points above that of all population (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Trends in household risk of poverty and exclusion by disability, Portugal and EU (EU-SILC 2013)

Of crisis, coalitions. . . and enduring austerity

In the final section of this article we turn our attention to the role of civil society to examine how the agency of people with disabilities is contributing to reshape the political landscape of disability policy and politics in Portugal. In examining the diffusion of disability rights in Europe, Vanhala (Reference Vanhala2015) argues that conventional theories highlighting the role of state elites in policy change are incomplete. She makes the case for complementing these approaches with a consideration of ‘the mediating role that domestic political institutions and the meaning frames adopted by civil society actors play in accounting for how and why rights travel’ (p. 834). Her case study of Cyprus, one of the first EU countries to adopt disability rights-based legislation despite its ‘troubled political history’, shows the relevance of a strong and cohesive disability identity politics at grassroots level in pushing for legal and social change. Her arguments resonate with the Portuguese case.

Indeed, persons with disabilities in Portugal have historically been an invisible and voiceless group, with low political participation and reduced ability to claim their rights (Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Casanova, Pedroso, Mota, Gomes, Seiceria, Fabela and Alves2007). The Portuguese disability movement has been described as fragmented and weak, highly dependent on State funding and more concerned with the provision of services than with rights claiming (Pinto, Reference Pinto2011). Although it was a disabled people's organisation – Associação Portuguesa de Deficientes (APD), a founding member of DPI, Disabled People International – that first introduced the disability rights rethoric in Portugal, back in the 1990s, the political divisions that characterised the disability movement at the time, the lack of consensus about what the goals and direction of disability policy should be, and the powerful and more numerous sector of individual-medical, care oriented, service-provider organisations, isolated APD's political voice and limited its impact. With the cuts on public spending introduced during the economic crisis, many disability organisations struggled to survive and this further affected their ability to advocate rights (Fontes, Reference Fontes2009).

During the austerity years, however, politics began to change. Inspired by international social movements like Occupy Wall Street in New York and 15M in Spain, on 15th September 2012 in Portugal, a large protest against the Troika – ‘Que se lixe a Troika! Queremos as nossas vidas!’ - was convened by a group of citizens connected through social media. According to the organisers, one million persons demonstrated on that day in various cities of the country against the austerity measures being implemented by the Conservative-led government of the day. Persons with disabilities were also involved in this protest, but they emerged as a specific group self-identified as the (D)eficientes Indignados.

In the beginning (D)eficientes Indignados were just a handful of activists but through social media the word quickly spread around and at each protest more people showed up. Initially the group mobilised around issues such as the lack of accessibility, the provision of assistive devices (an area that had been severely affected by government cuts) or the cutbacks on disability pensions, but from 2013 on the focus turned to claiming the Personal Assistance/Independent Living scheme. Some of the protests and vigils took place in front of the Parliament, always attracting a great deal of attention from the media. In addition to street demonstrations, with ever increasing numbers of activists of all ages in wheelchairs and crutches and their allies, the movement used new and dramatic strategies, turning their bodies into ‘tools for intervention’ (Sánchez Criado et al., 2015) to convey their political messages. A group of disabled activists locked themselves up in cages while wearing traditional prisoners’ uniforms to illustrate the kind of confinement that disabled persons experience in their lives, due to lack of support and accessibility; another activist started a hunger strike and laid down in a hospital bed in front of the Parliament, surrounded and supported by his disabled peers, until the State Secretary of Solidarity and Social Security accepted to meet with the group to discuss the new Personal Assistance/Independent Living legislation.

These ‘embodied politics’ (Arenas Conejo and Pié Balaguer, Reference Arenas Conejo and Pié Balaguer2014) had a powerful impact. Similar to experiences unfolding in Spain, also led by disabled activists and their coalitions (see for example, the EST processes involving the open prototyping of a portable ramp, described by Sánchez Criado et al., Reference Sánchez Criado, Rodríguez-Giralt and Mencaroni2016), these political activities were meant to be dialogic, in the sense of attracting public attention and locating disabled bodies, and through them, disability rights’ debates, in the public space (Arenas Conejo and Pié Balaguer, Reference Arenas Conejo and Pié Balaguer2014). The stories and pictures made it to the front page of the most important newspapers and were broadcasted by major TV channels. Portuguese society had never seen anything like this. Until then a largely ignored topic, disability issues raised significantly in the media agenda and the public opinion. More importantly, the movement draw heavily on the CRPD to recast disability as a human rights issue:

We are not ‘victims’ of disability, we are victims of discrimination. It's society that denies us the right to live as citizens, that denies us basic rights like the right to education, work, housing and mobility (esquerda.net, 2012)

Engel and Munger (Reference Engel and Munger2003) argue that ‘identity (. . .) is the appropriate starting point for exploring how rights become active’ (p. 40). It is when individuals view themselves as unfairly treated and excluded from mainstream society by socially constructed barriers that they become conscious of the potential for legal rights to overturn the injustice they have endured. The new ‘meaning frame’ adopted by key disability activists (Vanhala, Reference Vanhala2015) successfully asserted an understanding of disability in Portugal as an experience of social oppression and a human rights issue; civil society actors in the disability movement followed the lead.

The political action taken by these activists had a further effect: the experience itself became ‘an empowering process for participants, creating a sense of solidarity, purpose, and collective strength that enhance[d] the movement’ (Shakespeare, Reference Shakespeare1993: 252). With a new coalition forged within the academia, previous divides were overcome and an historical consensus was reached in the disability movement around the development of the Alternative Monitoring Report to the CRPD Committee, during the process of evaluation of Portugal as State Party to the Convention in 2015–2016 (ODDH, 2015).

In response to these new politics and meaning frame, the Lisbon Social Rights City Council launched in December 2015 the first pilot project of PA/independent living in Portugal. Although of small scale, as it only targeted five persons with disabilities living in the city, the project has been a watershed in national disability politics and was highly publicised as the triumph of the new disability movement.

In the 2015 legislative elections, for the first time in the country, a person with disabilities, who was also one of the leaders of the movement (D)eficientes Indignados, was elected deputy to the national Parliament. Following the elections, a new government took office, supported by a coalition of left-wing parties that, in addition to the socialists, included the historical communist party and Bloco de Esquerda, a young left-wing party, viewed by some as radical.

The structure of the new government included a new State Secretariat of the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities and the Secretary appointed was also a person with disability and the former President of one of the most important disability organisations in Portugal. The programme of the new government stated right from the beginning:

The programme that is presented here is based on a strategy which ensures that,

while respecting all of Portugal's European and international commitments and firmly protecting national interests and the Portuguese economy within the European Union, makes it possible to turn the page on policies of austerity, to undertake a new development model based on knowledge and innovation, to defend the welfare state, and to provide a new impetus for convergence with the EU (Governo de Portugal, 2015; my translation and emphasis)

And yet, as pointed out before, austerity ‘may well exist even where it does not speak its name’ (Farnsworth and Irving, Reference Farnsworth, Irving, Farnsworth and Irving2015: 12). The threat pending on Portugal of additional sanctions or exclusion from the Eurozone if the deficit did not come under control, which lasted until June 2017, kept the government conservative when it came to public spending, despite its progressive political intentions.

Certainly the social benefits freeze, in place since 2011, ended in January 2016, but the updates were only modest. Deeper and long awaited reforms such as the adoption of a new Disability Strategy, the introduction of the Personal Assistance/Independent Living scheme or the revision of the disability social protection system are still lacking.

Only in the early months of 2017, two papers were released for public consultation on these subjects: the National Independent Living Model (MAVI), and the new Social Benefit for Inclusion (PSI). In the introductory lines of both documents, human rights principles were clearly stated as foundations for the new policies advanced, but the specific content of the measures proposed was timid, in some cases medically-driven and their scope age-bound and means-tested (as opposed to universal). Moreover, their implementation appears precarious and/or is envisaged over the long-run: in the case of MAVI, what is proposed is the possibility of channelling European structural funds to finance pilot projects, whereas PSI will be subjected to a ‘phased implementation’ that will start in the final trimester of 2017 and will extend up until 2019.

At the time of writing this article, none of these measures have yet been formally adopted, and so the extent to which the government will enact a proper rights agenda remains uncertain. What seems already evident is that, in spite of the rights discourse, austerity appears ‘enduring’ (Jessop, Reference Jessop, Farnsworth and Irving2015).

Conclusion

This article set out to explore the impact of the CRPD on disability policy in Portugal, in a political and economic context marked by austerity and fiscal restraint. As discussed earlier, legislation introduced at the turn of the century brought about a more universalistic approach and a rhetorical shift from charity to a rights-based approach to disability, as enshrined in the UN Convention. However, the change was never really achieved, as the country plunged into a deep economic and fiscal crisis, and budgetary priorities took precedent over the realisation of rights. More recently, a new political turn and the coming to power of a socialist coalition government opened up new expectations that, nevertheless, are slow to materialise.

This raises questions about how human rights norms get diffused and implemented (Vanhala, Reference Vanhala2015). As research has revealed (Pinto and Teixeira, Reference Pinto and Teixeira2012a; Reference Pinto and Teixeira2012b; Pinto et al., Reference Pinto, Cunha, Cardim, Amaro, Veiga and Teixeira2014), Portuguese citizens with disabilities continue to face serious obstacles to exercise their basic human rights: lack of accessibility, lack of personal assistance services, conditionality to access social benefits and persistant economic insecurity, in particular, create significant barriers to social participation and a life with dignity.

What appears evident is that, when disability rights travel, they do not so in the void. Rather they meet with domestic institutional logics, local politics and the evolving meanings that social movements attribute to disability and rights at national level. They are also likely to face the cruel limits of public spending choices in times of austerity, that rarely benefit people with disabilities. From their encounter, and the shifting balance among actors at all these levels, new tensions emerge. The outcome is more than often hybrid law and policy models that keep or revive some of the old features (medical, conditional) while adopting new ones, or promising to do so.

In Portugal, the onset of the crisis and the state of ‘enduring austerity’ it inaugurated has created an inescapable paradox for disability policy in Portugal: despite its formal commitment to human rights, the State operates under a neoliberal agenda that prioritises fiscal restraint. In more recent times, this paradox has even created a sort of institutional dissonance, between a rights talk and a practice that comes in tension with rights principles. In a financially precarious context, ‘category-based’ approaches (Winance et al., Reference Winance, Ville and Ravaud2007), that place conditionality on access to benefits, supports and services on the basis of medical diagnoses, are particularly attractive to the State, as they constitute a powerful strategy to control public expenditure. So they are less likely to disappear.

At the same time, however, we are witnessing the emergence of a new disability meaning-frame in some countries (Vanhala, Reference Vanhala2015) led by a stronger and more cohesive than ever disability movement. Some of its leaders today are occupying political positions with larger capacity of influence. There is also an unprecedented interest of the academy on disability issues and disability rights with new alliances being forged, as the one that developed for the preparation and submission of the alternative report to the CRPD Committee in 2016. Such alliances will certainly not be exempt from difficulties, as tensions and contradictory demands from both sides will always arise. Nevertheless, and in spite of the very difficult context, these new coalitions speak louder and with stronger voice than each of its constituencies can do. It remains to be seen whether such voices will be able to shape, influence and change disability policy and the realisation of disability rights in Portugal in the years to come.

Acknowledgments

A related article has been published by Minority Reports: Cultural Disability Studies, 2, 2016.