Introduction

‘Just transition’ (JT) is a concept originally developed by the labour movement to reconcile workers’ rights and employment security with the necessity to combat climate change (Stevis and Felli, Reference Stevis and Felli2015; McCauley and Heffron, Reference McCauley and Heffron2018; Galgóczi, Reference Galgóczi, Räthzel, Stevis and Uzzell2021). More recently, supra- and international organisations as diverse as the European Union (EU) or the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have embraced the idea of a just transition to steer countries towards sustainable economic development. However, it remains unclear to what extent such international actors follow the eco-social ambitions of organised labour or redefine the concept in ways that deviate from its originally intended meaning.

In this article, we investigate the diverse usages and understandings of a just transition among supra- and international actors, with the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the IMF, and the EU selected as cases to test the usefulness of our suggested framework. Going beyond the mainly normative discussions in the just transition literature (e.g. Pai et al., Reference Pai, Harrison and Zerriffi2020; Wang and Lo, Reference Wang and Lo2021) and drawing from more recent contributions in the field of eco-social policy, our article (1) develops a conceptual framework to capture diverse JT approaches and (2) analyses the prevailing varieties of emerging eco-social policy mixes that we find empirically at the European and international level. In this way, we add to the literature of comparative social policy and political economy by providing future scholarship with conceptual and operational clarity when investigating the eco-social policy mixes advocated by actors as diverse as the EU, international organisations (IOs), governments, political parties, or interest groups. Our article has also important political implications, given that the EU and other international organisations are central agenda-setters for the adoption of ‘just transition’ frameworks at the domestic level (Sabato and Fronteddu, Reference Sabato and Fronteddu2020).

Empirically, we identify a cleavage between the ILO where just transition refers to a fairly ambitious eco-social agenda, and the other organisations in which the concept is used in a more constrained or uneven fashion, e.g. by focusing on economic aims at the expense of social or environmental objectives. To understand differences in the usage of the term, we believe it is important to understand the differing objectives, degrees of autonomy and competences of these actors, as this bears on the feasibility of a new common paradigm of eco-social policies emerging.

Our article proceeds as follows. In the next section, we develop a conceptual and operational framework to capture possible varieties of a just transition, before describing our multi-method approach. In the following empirical section, we apply our framework to discuss the case studies of the IMF, the EU, and the ILO. The final section summarises the results and discusses avenues for further research.

Just transition: definition, background and objectives

Building on previous scholarship, we define just transition as ‘a fair and equitable process of moving towards a post-carbon society’ (McCauley and Heffron, Reference McCauley and Heffron2018). While this definition is useful for analytical purposes, the term is in many ways fuzzy and prone to different interpretations (Stevis and Felli, Reference Stevis and Felli2020). Our research interest lies in how the concept of a ‘just transition’ has been appropriated and re-interpreted by political actors (in this case beyond the nation state) over time.

The term goes back to North American workers’ activism vis à vis new environmental regulations in the 1960-70s. In the United Stated (US), the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers’ Union (OCAW) and its leader Tony Mazzocchi argued that the goal of saving jobs should not be traded off against the banishment of products harming workers’ health and their communities (Stevis and Felli, Reference Stevis and Felli2015; Galgóczi, Reference Galgóczi, Räthzel, Stevis and Uzzell2021). The union movement soon coalesced with environmental groups to rebuff the ‘jobs vs environment’ discourse advanced by polluting industries. In the following years, OCAW also proposed a ‘superfund for workers’ to stimulate training and reallocation after the closure of toxic facilities (Wang and Lo, Reference Wang and Lo2021).

Starting from the 1990s, the concept of a just transition broadened in scope, gaining traction among non-governmental organisations and international organisations. In the 1990s-2000s, the global workers’ movement promoted a ‘just transition’ in the context of climate change conventions and negotiations. The predecessor of the International Trade Union Confederation[Footnote 1] included the idea in a statement to the Kyoto Conference in 1997. In 2010, the final declaration of the Climate Change Conference in Cancun prioritised ‘a just transition of the workforce that creates decent work and quality jobs’ (UN, 2010: 4). Five years later, this passage was included in the preamble to the landmark Paris climate conference agreement (UN, 2015). Finally, the Heads of State and Government at the COP24 in Katowice made an explicit commitment towards ‘Solidarity and Just Transition’ (Sabato and Fronteddu, Reference Sabato and Fronteddu2020), in what can be seen as the ‘highest level of political recognition’ of a just transition to date (Bergamaschi, Reference Bergamaschi2020: 2).

Among other institutions, the ILO took crucial steps for the systematisation of the concept and its acceptance in the broader institutional sphere. From 2008 onwards, the ILO worked on the development of a ‘just transition framework’. This process culminated with a set of ‘Guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all’ (ILO, 2015), which soon became a pillar of just transition strategies worldwide. While setting the goal of a socially just, inclusive, and carbon-free economic model, the guidelines also emphasised the procedural side of a just transition – that is, the need to ‘promote and engage in social dialogue at all stages and at all levels’ and involve all the relevant stakeholders in the policy-making process (Galgóczi, Reference Galgóczi2020).

Despite its rising popularity, the idea of a just transition is frequently seen as multi-faceted. For instance, Stevis and Felli (Reference Stevis and Felli2015) distinguish between ‘affirmative’ versions of a just transition (i.e. pursuing equity and de-carbonisation within the current institutional framework), and ‘transformative’ versions of it, entailing a more structural rethinking of political economies and power relations between actors. Secondly, scholars have discussed which goals it should encompass, ranging from ‘distributive’ to ‘restorative’ and ‘procedural’ aspects (McCauley and Heffron, Reference McCauley and Heffron2018). Moreover, the scope of the concept has been under scrutiny (Mandelli, Reference Mandelli2022: 12). ‘Narrow’ formulations of a just transition – which stress its impact on specific industries or groups such as workers – have been seen as separate from ‘broad’ interpretations of the concept, which account for its effects on a larger number of stakeholders and their communities. As a working definition in the context of this article, we deliberately opt for a broad and relatively simple concept of a just transition – that is, a strategy for pursuing the de-carbonisation of the economy while keeping with the goals of social justice and inequality reduction.

A Framework for Analysing Just Transition Approaches of Supra- and International Organisations

As discussed in the previous section, just transition is a political reform strategy aiming for a balanced approach towards the problem of the ‘eco-social-growth trilemma’ (Mandelli et al., Reference Mandelli, Sabato and Jessoula2021). The eco-social-growth trilemma is an analytical construct that refers to the potential challenges and trade-offs of simultaneously achieving the three goals of economic growth, environmental protection (decarbonisation) and social welfare. Essential to the goal of a just transition is to ensure that environmental protection does not lead to increasing social inequality. However, throughout human history reducing inequalities has been closely connected to fossil-fuelled economic growth, which runs counter to the existential necessity of a carbon-neutral environmental transformation of the economy and society. Given the multi-faceted character of a just transition (Mandelli, Reference Mandelli2022), we propose a framework to operationalise its theoretical dimensions into empirically detectable traits. Building on previous work (e.g. Rogge and Reichardt, Reference Rogge and Reichardt2016; Hirvilammi and Koch, Reference Hirvilammi and Koch2020; Mandelli et al., Reference Mandelli, Sabato and Jessoula2021; Mandelli, Reference Mandelli2022), we distinguish three relevant dimensions for just transition policy approaches of organisations: the goal dimension, the policy dimension and the governance dimension.

First, we assess the relative importance that our selected supra- and international organisations attach to different goals within the eco-social-growth triangle. The concept of a just transition aims to simultaneously move towards a ‘green economy’ in an ecologically sustainable and socially just way (Laurent, Reference Laurent2021; Mandelli et al., Reference Mandelli, Sabato and Jessoula2021). However, we expect that in practice just transition strategies of supra- or international actors may inherently apply an internal goal hierarchy based on their political mandate. For instance, it is likely that the IMF will give economic growth and financial stability a more central position when talking about a just transition than the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which is likely to focus more strongly on climate protection.

Second, we assess the welfare reform policies advocated to achieve the promoted just transition goals. Just transition stances can vary regarding the prioritisation of social policy measures for managing social risks and needs emerging from the climate crisis and greening policies. Therefore, we follow recent research in differentiating between ‘social protection’ and ‘social investment’ policies (Mandelli, Reference Mandelli2022). While the former aims at compensating citizens/workers for income losses through (early) retirement, unemployment benefits and other social transfers (‘repair’ function), the latter focuses on long-term human capital formation (through education, childcare, active labour market policies, research and development) to enhance and update workers’ skills (‘prepare’ function) (Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Garritzmann, Palier, Garritzmann, Häusermann and Palier2022). Regarding just transition, a social protection measure would be, for example, an early retirement scheme to compensate workers for the closure of a coal-fired power plant, while social investment could include reskilling after the decommissioning of the same plant. It is important to note that these two approaches are not mutually exclusive.

From a policy standpoint, JT stances can also vary regarding the scope of public intervention and the role of the state, differentiating between weak-state intervention and strong-state intervention (Beramendi et al., Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt, Kriesi and P. Beramendi2015). Weak-state intervention policies rely on a limited regulatory and financial state involvement (e.g. in the form of social benefits) as they advocate market-based solutions and promote corporate social responsibility in climate transition. Strong-state intervention policies refer to an active involvement of the state as a central actor for securing a socially just and green transition of the economy, e.g. through welfare benefits or regulatory policies.

Third, we analyse the governance dimension of JT approaches, e.g. the strategies of policy implementation and enforcement promoted by the EU and IOs. Whereas these actors have been relevant agenda-setters of JT in recent years, welfare-climate policy formulation and implementation are still mainly national competences. However, governance competences of IOs, and especially the EU as a ‘supranational federation’ (von Bogdandy, Reference von Bogdandy, Jones, Menon and Weatherill2013), can differ, especially the extent to which ‘just transition’ entails binding agreements with attached conditionalities or remains discretionary. Here, we rely on research conceptualising governance competences on a continuum between non-law and hard law governance (e.g. Saurugger and Terpan, Reference Saurugger and Terpan2021). Governance competences are defined based on obligation and enforcement. Thus, just transition approaches of the EU and both ILO and IMF can differ related to the bindingness of promoted goals, targets, etc. and the capacity to reward or sanction (member) states if these obligations are not fulfilled. Based on Saurugger and Terpan (Reference Saurugger and Terpan2021), we distinguish four potential governance modes:

-

no law (no obligations + no enforcement)

-

soft law (soft obligation + soft enforcement)

-

hard (soft) law (hard obligations + no/soft enforcement)

-

hard law (hard obligations + hard enforcement).

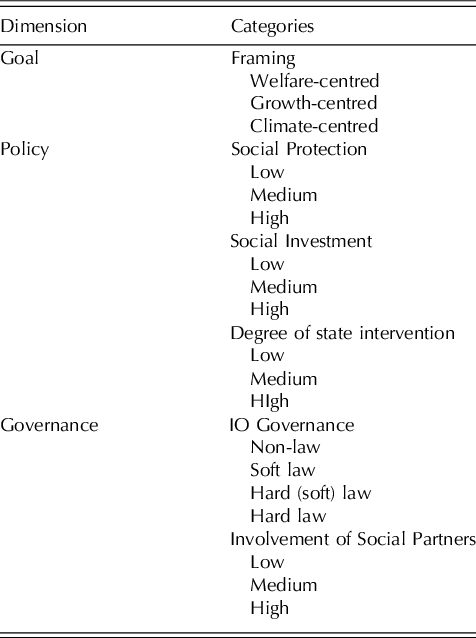

Finally, our framework also looks at the role given to non-state actors, especially social partners as well as civil society in the governance of eco-social transformation. Here, we simply differentiate between the categories of weak and strong involvement. Table 1 summarises our different dimensions and possible sub-categories.

Table 1. Dimensions and categories for analysing just transition approaches

Methodology

We apply a multi-method approach to gauge the extent of variation in just transition strategies across supra- and international actors. Based on the most recent key documents for each organisation examined, we first employ natural language processing and text mining techniques to pinpoint differences in just transition narratives. Frequency tables are used to gauge how central a word is based on its collocations with other relevant words in a text. The comparison of word usage allows for a first standardised assessment of the way the EU, the IMF and the ILO frame their idea of a just transition, and the concepts they emphasise.

For this part, we selected five policy documents for each organisation in the period from 2019 until the time of final analysis at the end of 2022, comparable in type and length and focusing on the issue of climate change/just transition (see Appendix 1). These include broader framework documents as well as technical or staff working documents, but exclude direct legislation, as only the EU has law-setting abilities. We focus on this relatively short period as our aim is not to trace the development of the just transition concept over time, but to give a cross-sectional picture of how our three selected organisations discuss policy solutions for a necessary economic transition in the face of climate change in the aftermath of the historic Paris Agreement in 2015.

The EU launched a ‘European Green Deal’ at the end of 2019. As an overarching framework for the current European Commission to reach climate neutrality by 2050, it represents a sensible starting point for the EU case. The ILO has most explicitly used the term ‘just transition’ since 2019, not least including it in the title of its key documents, while the documents for the IMF only cover the years 2021 and 2022, indicating a latecomer status of the IMF to the debate. We have relied on the IMF’s staff climate notes, as they reflect the organisation’s most policy-relevant documents on the nexus between the economy, welfare, and climate change. The term ‘just transition’ is mentioned there on several occasions (e.g. IMF, 2022d), but it overall features less prominently among the IMF’s documents in comparison to the other two organisations.

In the second part, we adopt a qualitative approach to gain further insights into discourses and policy suggestions when referring to a just transition framework. For this, further reference documents of the three cases are included and analysed. First, we assess the relative importance organisations attach to economic growth, social objectives, and environmental protection in relation to the goal dimension. Second, we look at the emphasis of just transition approaches devoted to both social investment- and protection-oriented policies, as well as the desired degree of state involvement (policy dimension). Third, we investigate strategies of policy implementation and enforcement, especially the extent to which ‘just transition’ entails binding agreements with attached conditionalities or remains discretionary (governance dimension), as well as possible interactions with social partners.

Quantitative text analysis

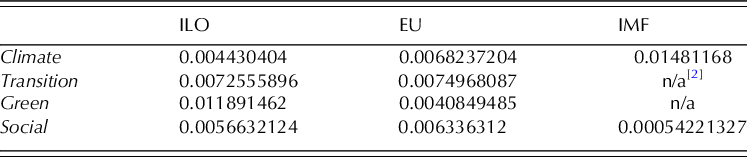

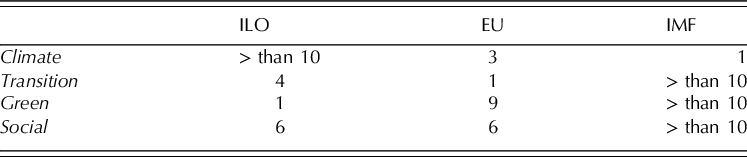

We first used the NVivo software to compare the word frequencies of JT-related concepts across the three cases. Tables 2 and 3 present relative frequencies and rankings of four key words we selected (‘climate’, ‘transition’, ‘green’ and ‘social’). We picked the terms that appeared among the ten most frequent words for at least two of the three organisations under scrutiny.

Table 2. Word usage for three organisations (frequency per million words)

Table 3. Ranking of word usage per organisation

The ILO and the EU seem to adopt a just transition frame to a much greater extent than the IMF. ‘Transition’ ranks highly for the EU (first) and the ILO (fourth), and the word ‘social’ is the sixth most used by both actors. By contrast, ‘climate’ is the most mentioned word by the IMF. The word ‘green’ is relevant especially for the ILO (first) but also for the EU (ninth) (see Table 3).

For the IMF, the picture looks quite different. The words ‘transition’, ‘green’ and ‘social’, generally associated with the idea of a just transition, all fall out of the top ten. The IMF documents focus predominantly on economic growth: together with ‘change’, ‘emissions’ and ‘carbon’, frequently employed terms are ‘costs’ and ‘Gross Domestic Product (GDP)’ (see Appendix 2 for more details). As detailed in the qualitative section, for the IMF the idea of ‘adaptation’ entails a ‘green’ side, but primarily in the sense that it fulfils the priority of (carbon-neutral) economic growth. Planetary boundaries are mostly factored in as potential constraints to economic success.

On the other hand, the ILO and the EU frame their narratives more in terms of inclusive (green) growth, job creation and redistribution. The ten most diffused words for the ILO reflect a clear interest in labour issues (‘jobs’, ‘employment’, ‘skills’), as well as the normative aspect enshrined in JT (‘social’, ‘sustainable’, ‘just’). The ILO framework aims to promote a new economic paradigm centred on the creation of green jobs and the shift towards a more equitable society. For the ILO, these two elements cannot but go in tandem. Despite placing less importance on employment per se, the EU likewise stresses the welfare dimension as well as ‘energy’-related issues. Other widely used words relate to more procedural aspects (‘European’, ‘member’, ‘commission’, ‘states’).

Having sketched the main priorities and concerns of the three actors, the next part proposes a qualitative content analysis to corroborate these results and gain a fuller understanding of the respective approaches towards the operationalisation of the concept.

The IMF - economic adaptation instead of just transition

The IMF clearly prioritises the growth dimension of decarbonisation relative to its welfare dimension (IMF, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c, 2022a, 2022b, 2022c, 2022d). Its reports are more detailed than those by the EU and ILO in assessing the economic-environmental status quo of climate mitigation pledges and policies. In the past four years, the IMF has stepped up efforts in this stocktaking exercise considerably, reflected in a host of flagship reports, policy papers, and in bilateral country reports (for an overview, see IMF, 2021c). At the same time, however, the IMF’s approach remains technocratic in character, as it pays little attention to questions of political consensus mobilisation. In other words, the IMF’s climate notes prioritise economic management issues over questions of how to achieve political support for the ‘necessary’ reforms it outlines in its policy recommendations.

The IMF’s economic rationale comes out clearly in the opening statement of its Executive Board on how to help member states in addressing climate change: ‘The paper highlights macro-critical climate-related policy challenges that will confront all IMF members in the coming years and decades. For example, global warming is bound to undermine productivity and growth, affecting fiscal positions and debt trajectories. It will also impact asset valuations, with repercussions for financial stability. Further, climate change will redistribute income across the globe, which will influence trade patterns and exchange rate valuations’ (IMF, 2021c: 1; italics are our own).

Drawing on region- and country-level data in comparing greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) at a global scale, the IMF’s most favoured policy tool to address climate change is the introduction (and increase) of carbon taxes to facilitate net-zero targets while keeping the economy afloat (IMF, 2021a, 2022d). The logic behind the IMF’s reliance on carbon taxation is micro-economic in nature: when rational individual agents face higher costs from producing GHGs, they have an incentive to change their behaviour towards decarbonisation. Although infrastructure investments, regulatory measures, and sectoral policies are recommended in a few sections as well, they are deemed subordinate to carbon taxation, because the latter is meant to be the single most efficient policy tool available to governments.

An additional reason why carbon taxes are proposed so forcefully is that they may boost the economy by creating fiscal space for cuts in labour taxation. This way, governments can offset negative GDP impacts resulting from decarbonisation (‘abatement costs’) and may turn vice into virtue through a business-friendly use of carbon tax revenues. Moreover, the IMF motivates higher carbon taxation as a way of helping to reduce local air pollution mortality alongside global climate effects. From an international perspective, the IMF urges developed countries to support developing countries in their efforts towards decarbonisation through financial support and technological transfer (ibid.: 10). In a similar vein, the IMF has proposed a carbon price floor arrangement among large emitting countries to scale up global carbon pricing.

Further proof of the IMF’s prioritisation of the growth dimension, and weakly envisaged degree of state intervention, comes from its proposal for ‘Green Public Finance Management’ (GFPM), involving a set of guidelines aimed at integrating climate objectives into fiscal policymaking (IMF, 2021b). After outlining a policy stages approach in the implementation of GFPM, the IMF emphasises ‘political leadership’ (ibid.: 14) required from domestic Ministries of Finance to push such an agenda forward. While the IMF’s report suggests ensuring ‘buy-in’ (ibid.: 15) through regular communication with relevant stakeholders, the overall political logic of the proposal essentially relies on a strong executive able to overcome political veto players.

Most recently, the IMF’s key term on the climate-economy nexus is the one of adaptation, defined as ‘the process needed to minimise losses and maximise benefits from climate change’ (IMF, 2022a: 3). It starts from the premise that ‘[c]limate is changing and will continue to change even with intensive mitigation efforts’ (ibid.,: 2). Rather than framing climate change as an opportunity or necessity to transition into a new type of economy, the IMF advocates for ‘constant and dynamic readjustment of consumption, production, and public policies’, which would resemble an ‘optimization problem under uncertainty’ (ibid.,: 3). Conceived in this way, the challenge of adaptation is to find effective policies without possessing the information necessary to assign exact probabilities to the various outcomes of different policy choices, thus the emphasis on uncertainty. At its most basic, the implication for the IMF is to integrate climate risks and the costs of adaptation into macro-fiscal policymaking, thereby factoring in the costs of short-term climate disasters, long-term risks arising from changes in both average and extreme events, and related adaptation policies (IMF, 2022b). While acknowledging that global heating is unavoidable, the IMF further argues that adaptation needs to go hand in hand with ‘mitigation’, because adaptation alone would otherwise become either impossible or too expensive (IMF, 2022c). The task is therefore to prevent climate risks and their impacts as much as possible.

Whereas the IMF’s reports are meticulous in defining problems and solutions for the reconciliation of economic and environmental objectives, it is much less outspoken on the welfare dimension of net-zero transitions. The term JT is not only mentioned little in quantitative terms in key documents; it is also more restrictively defined in its qualitative scope, i.e. focusing only on ‘vulnerable groups’ (IMF, 2021a: 12) and providing merely ‘targeted assistance’ (IMF, 2021b: 3). Elsewhere, there are vague mentions of a ‘just transition’ (IMF, 2021c: 10), which should accordingly ensure to ‘repurpose human and physical capital’ (ibid.) and build infrastructure for a low-carbon economy (IMF, 2019, 2020). More recently, the term resurfaces in a different light (IMF, 2022a: 3), implying that a ‘just transition’ requires international support for small and vulnerable developing economies to help them in their adaptation efforts. In another context, the IMF (2022c: 8) recommends ‘social safety nets’ to alleviate the adverse impacts from both extreme events and slow-moving climate transformations.

The most recent IMF flagship report (IMF, 2022d) has the term ‘Just Transition’ in its title, but the concept is not clearly specified in the main body of the text. In line with previous IMF policy papers, the general thrust of the report is that high-income countries need to cut emissions most, preferably with the use of increased carbon taxation, and provide cash transfers to low- and medium-income countries in order to accelerate their decarbonisation efforts. In other words, the IMF’s notion of ‘justice’ seems to be that the developed countries take the lead in reducing emissions, both at home and abroad. Taken together, the IMF’s usage of the ‘just transition’ concept is rather defensive and residual. Within the social policy domain, the measures mostly fall into our social protection category, geared to compensate the losers of decarbonisation, while mentioning ‘socially productive investments’ at one point (IMF, 2021a: 12), but without providing any further details.

When it comes to the governance dimension, the IMF’s framing is one of ‘soft law’ – that is, ‘assisting members’ in responding to climate change (IMF, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c). Interestingly, the Executive Board concedes that it has not had the resources necessary for covering macro-climate analysis until recently, perhaps to legitimise efforts to expand and train its workforce in this direction (IMF, 2021c: 8-9). To live up to its mandate to oversee economic development, lending, and capacity development, it however proposes to include climate change-related policy challenges in its Article IV consultations, i.e. in its member country visits every five to six years, and more frequently to the largest emitters of GHGs. It remains to be seen to what extent the IMF will make financial lending to its member states conditional on decarbonisation efforts.

The European Union – green growth supported by a Just Transition Fund

The EU emphasises all three elements – climate, welfare, and growth – of the transition. The European Green Deal (EGD) as the main instrument to achieve the just transition unmistakably provides an economic framing by introducing it as ‘Europe’s new growth strategy’ while highlighting the opportunity to take a new path of ‘sustainable and inclusive growth’ (European Commission, 2021a: 1). EU policies are simultaneously oriented at climate through the agreement on a binding target to achieve at least 55 per cent net GHG emission reductions by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels) and growth-oriented by pointing to the capacity of creating new jobs (European Commission, 2021b; European Commission, 2021c). As has already been argued by Sabato and Mandelli (Reference Sabato and Mandelli2018), the Commission’s approach towards addressing the climate crisis is a ‘green growth’ strategy that emphasises the win-win character of policy solutions and has been presented as affording a competitive advantage for European industries. Green growth assumes that continued GDP growth can be decoupled from carbon emissions at a sufficient rate to maintain current levels of prosperity and meet decarbonisation goals (Hickel and Kallis, Reference Hickel and Kallis2020). The European Commission (EC) cites evidence that ‘decarbonisation and economic growth can go hand in hand’ (European Commission, 2021a: 2). Efficiency savings are promised through the modernisation of energy, mobility, and housing thus ensuring affordable access to essential services for the most vulnerable while creating new jobs and meeting climate targets (European Commission, 2019; European Commission, 2021b).

Green growth is complemented by the principle of JT that has been adopted from the ILO (European Commission, 2021a). When speaking of the social dimension of the green transition, reference is made to the European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR). Despite the rights-based language, the EPSR is a set of legally non-binding principles relying on soft-law mechanisms. However, financial means are being put behind achieving a fair green transition in the form of the Just Transition Fund (JTF), a €17.5 billion investment in the 2021-2027 financial framework (European Commission, 2020) that is made available for the territories most affected by the transition to a green economy, following the slogan of ‘leaving no region behind’ (European Commission, 2021b: 1). Emphasis is placed on active labour market policies to reskill or upskill workers made redundant by the green transition, thus clearly following a social investment logic, but also on adequate social protection and compensatory income support to facilitate the necessary labour market transitions (European Commission, 2021a). While it is noteworthy that early retirement schemes will explicitly not be financed by the JTF (European Commission, 2021b: 11), transfers and subsidies are still seen as important to counter certain regressive or disproportionate effects on low-income households, also to garner social acceptance of the implemented measures (European Commission, 2021c).

There is an explicit reference to the ‘social’ component of just (interchangeably called fair) transition. The primary social impact of the green transition is linked to job losses in fossil-fuel extracting and GHG-intensive sectors. Closely related, the expected GDP decline in regions depending on these sectors is seen as the major economic impact. However, broader welfare impacts, such as those on community cohesiveness, living conditions or energy poverty are also acknowledged (European Commission, 2021a). Indeed, the EU is very concerned with energy issues. A closer look indicates that EU priorities in terms of just transition are divided between ‘social’ concerns in general and ‘energy’ as a more particular sector to meet the twin aims of energy security and energy affordability. The process itself is framed as a transition, as opposed to the IMF which describes it as an adaptation.

Many of the key policy areas intersecting when it comes to a green transition – notably, energy, environmental and social policy – are mainly member state competences, which explains the prominence of the term ‘member’ (state) in our quantitative findings as well as the mainly soft-law character of the social measures suggested to mitigate impacts of the green transition. Regarding the governance dimensions, the Commission furthermore takes a consultative approach to legislating for a ‘fair transition’. Consulted bodies include social actors such as the Employment Committee and the Social Protection Committee as well as the European social partners and civil society organisations active in the social and employment areas, but also economic actors such as the Economic Policy Committee (European Commission, 2021c). Nevertheless, regarding energy and climate policy, binding legislation has been introduced in the past and updated in 2021 with the ‘Fit for 55’ package (European Commission, 2021d). This includes updates on the EU’s Emissions Trading System (i.e. a market-based mechanism to reduce emissions), Directives on energy taxes as well as Regulations on CO2 and GHG emissions. To address the distributional impacts of emission trading and the ‘Fit for 55’ package on vulnerable households, transport users and micro-enterprises, a €65bn Social Climate Fund was proposed in 2021 (European Commission, 2021d) and adopted in 2023. The ‘Fit for 55’ package will also try incentivising public and private investments into ‘green markets’ such as low-emission vehicles. In terms of economic policy, a middle position is thus taken when it comes to the role of state intervention as a use of direct legislation and regulation at EU level is combined with incentives for economic actors as expressed through using measures such as carbon pricing (European Commission, 2019). Overall, an ‘affirmative’ rather than a ‘transformative’ version of JT is promoted by the EU.

The ILO – social rights and sustainability

The position of the ILO regarding the notion of JT is in many respects different from the IMF and the EU. The reasons behind these differences are twofold: first, the ILO was one of the first organisations which claimed ownership of the processes we now refer to as just transition. Second, the notion of JT largely overlaps with the ILO’s mission of ‘setting labour standards, developing policies and devising programmes promoting decent work for all women and men’ (ILO, mission and impact statements). While all three dimensions of JT are present in ILO documents, more weight is put on the welfare and climate dimension, while the growth dimension is seen as largely secondary and instrumental.

One of the earliest instruments outlining actionable indications for states are the ILO’s ‘Guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all’ (ILO, 2015). This document not only served as a framing document for the ILO agenda but was at the same time a stepping stone for member states as well as other organisations to frame their approaches to streamlining social policies into plans for more substantive, greener growth. The Guidelines state the ILO’s general approach to JT – namely, that sustainable development has three interconnected, equally important pillars (economic, social and environmental) and that they must be addressed in a coordinated manner.

However, the ILO itself has a slightly different approach to the implementation of just transition efforts. Before 2017, the notions of ‘decent work’ and ‘green jobs’ were considered two separate agendas. Following the publication of a strategy report on decent work (Poschen, Reference Poschen2017), the ILO combined these two, thereby adopting the notion that current financial and environmental crises can be turned into an opportunity to create decent work for all through the introduction of green jobs, which would ultimately help the shift towards more sustainable development (ILO, 2015: 4). As stipulated by this approach, mainstreaming environmental sustainability (climate dimension) in national ‘decent work’ employment policies (welfare dimension) needs to be done through cooperation and social dialogue between all stakeholders, including but not limited to governments, private actors, and trade unions (ILO, 2015: 4). The document describes in detail the ‘how’ of this process, focusing on cooperation, coordination and joint efforts towards achieving environmental and social outcomes. Thus, for example, the ILO recommends that countries keep not one single ministry accountable for implementation of just transition, but several (finance, planning, environment, energy, transport, health and economic and social development) (ILO, 2015).

While the ILO recognises the financial toll of a just transition (growth dimension), it does so to anticipate potential social asymmetries the transition may create. However, contrary to the IMF, issues of costs, risks, and budgets do not seem to take centre stage in the ILO’s work. Our analysis confirms that social and environmental aspects are much more prevalent in ILO documents. The growth dimension, albeit present, is geared towards ensuring that there is equitable redistribution through policy solutions at a national level. The analysis seems to corroborate that, in line with its mission, the ILO is preoccupied first and foremost with developing the framework for implementation of JT. By doing so, it gives programmatic guidance to UN member states, but also provides sectoral advice as well as guidelines for procedures and instruments to be integrated into existing legislation. This way, the ILO aims to transform both (decision-making) ‘processes’ as well as ‘workplaces’ (ILO, 2022c: 8).

Overall, the ILO seems to have a leading position on the welfare dimension of JT, a moderate position in terms of climate, and a weak emphasis on the growth dimension. Even though policy domains at the heart of the ILO’s agenda, such as social security and benefits, are very closely related to issues of budgets and quotas (which the IMF and EU are more concerned with), there seems to be little substantive overlap between ILO’s areas of ownership and the other two institutions.

The ILO’s social policy approach is heavily focused on social security, with its main aim to ensure a minimum income and decent existence for all (ILO, 2008). The ILO’s operating paradigm, therefore, is that social protection floors should be in place to combat poverty and inequality, and that further investment will follow suit once these basic needs are addressed, particularly in terms of ensuring decent work (Dur, Reference Dur2017). Social investment as a strategy for skills development to green jobs and education is also an important item on the ILO agenda (ILO, 2022c). However, the ILO emphasises that skills development has to be coupled with active labour market policies and the aforementioned social protection floors, especially prioritising the needs of vulnerable groups. Overall, in the policy dimension the ILO puts the highest emphasis on social protection and social investment of the three international organisations.

In its governance, the ILO is bound to soft law, meaning they provide policy recommendations and guidelines informed by findings of their own projects. As a tripartite organisation, the ILO recommends to ‘provide opportunities for the participation of social partners at all possible levels and stages of the policy process’ (ILO, 2015: 8) and emphasises that ‘[…] it is crucially important to involve those who will be impacted – workers, employers, communities – in the decisions to be made’ (ILO, 2022b: 3). This ‘what works’ approach is reflected in one major document dealing with concrete recommendations on social protection - the ‘Social Protection Floors Recommendation no. 202’ (ILO, 2012). In terms of implementation, the ILO tries to keep the country programmes tailor-made for the specific set of issues respective countries face. Involvement of social partners is recognised as key to achieving desired outcomes.

Discussion and conclusion

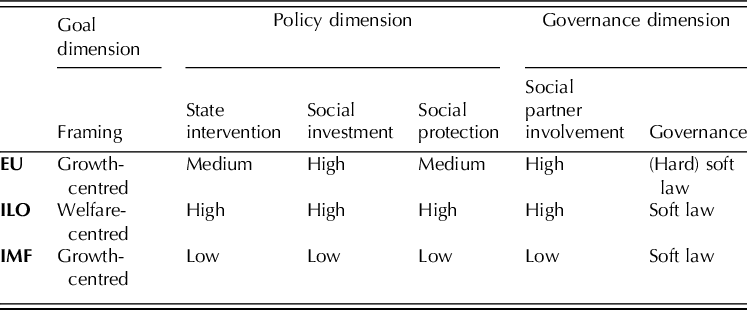

JT frameworks have gained growing currency considering the manifold challenges to reduce carbonisation without compromising on workers’ rights and social cohesion (Stevis and Felli, Reference Stevis and Felli2015; McCauley and Heffron, Reference McCauley and Heffron2018; Galgóczi, Reference Galgóczi2020). Originally developed by the labour movement, the JT concept is no longer used exclusively by those who have a union agenda in mind: governments, political parties, interest groups, media outlets, the EU and international organisations of different outlooks have come to draw on it and sometimes repackage it for their own purpose. Our article has therefore (1) developed a conceptual and operational framework to capture and analyse different notions of a just transition and (2) applied it to the study of agenda-setting documents from the ILO, the EU, and the IMF. In line with our expectations, we find empirically that the ILO’s original understanding and intention behind the just transition concept has been somewhat diluted by others in favour of economic growth objectives, especially in the case of the IMF.

Our analysis has shown that the IMF prioritises factors such as productivity and competitiveness, with social and environmental goals framed as ancillary aspects (Table 4). While paying attention to the employment and social policy mixes needed for JT, the EU promotes a green growth agenda, whereas the ILO is somewhat downplaying the growth dimension. This variation indicates the different roles in the development of a JT framework: on the one hand, the ILO can be seen as a ‘pioneer’ by first systematising the concept and mainstreaming it in its own agenda since the early 2010s. On the other hand, the EU and IMF may be regarded as ‘bandwagoners’, as they followed the trend by re-adapting their modi operandi to the goal of mitigating the climate crisis.

Table 4. Comparison of just transition approaches by cases

The cases studied adopt distinct frames on dimensions such as the envisaged role of the state, social policy mixes and governance. The IMF prioritises incentives for economic actors to (dis)invest in fossil-intensive sectors (mainly through carbon taxes). Unsurprisingly, it also leans towards a ‘soft-law’ approach, with no explicit mention of social partner involvement in the policy-making process. Social policies aimed at buffering the ‘adaptation’ (social protection) or preparing individuals to the risks attached to it (social investment) are far from central in the IMF’s strategy.

By contrast, both the EU and the ILO share an interest in social policy reforms. While the ILO focuses strongly on the need to shelter people and communities from income insecurity deriving from the climate crisis (protective function), to be combined with skill formation and training strategies for green jobs, the EU more strongly promotes an approach that combines social investment (mainly active labour market policies) with (selective) social protection. The ILO envisions a higher degree of state intervention than the EU, whose JT strategy mostly focuses on supranational programmes (JTF, ‘Fit for 55’). This difference can be explained by the fact that unlike the ILO, the EU has significant funding options at its own disposal. Both the ILO and the EU consider social partners’ participation as pivotal in steering the transition.

Our framework may have wider application in the study of JT. While selected supra- and international organisations are the focus of this article, there is still little (comparative) research on JT approaches of national political actors, i.e. political parties and interest groups. Future research may therefore draw on and refine our framework to capture and understand the domestic policy preferences underlying eco-social policies – for instance, through the study of election manifestos, press releases, and interest group documents. Another avenue of research would be to investigate the politics dimension in the study of policy-making processes that involve actors with invariably diverse interests in the eco-social policy domain.

Moreover, the study of JT strategies should engage further with the literature on global social policy, as it relates to the influence of international practices and ideas on national (social) policymaking. Recent literature has shown that these actors play an increasingly relevant role for the diffusion of welfare policy ideas and instruments (e.g. Jenson, Reference Jenson2017). As the popularity of the concept is growing fast, future research may look at how IOs’ JT strategies and frameworks are adopted or reformulated at the national level.

In an age marked not only by heightened distributive conflict but also by the demands of addressing climate change, JT frameworks are of central concern to political actors and industrial relations systems around the world. Our article thus provides a first step towards a careful empirical study of the emerging policy paradigms that underpin a just transition.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746423000192