The quality of life and longevity of older adults are influenced by social relationships, which protect against functional decline and promote resilience (Umberson et al., Reference Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu and Needham2006; World Health Organization, 2015). Research on couple relationships is robust in showing the protective effect that partner relationship has on physical and emotional well-being (Carr et al., Reference Carr, Freedman, Cornman and Schwarz2014; Carr & Springer, Reference Carr and Springer2010; Davila et al., Reference Davila, Bradbury, Cohan and Tochluk1997). Bryant et al. (Reference Bryant, Bei, Gilson, Komiti, Jackson and Judd2012) found that, compared to individuals who do not have a partner, participants with partners reported significantly lower symptoms of depression and anxiety and higher scores on general mental health and satisfaction with life. In addition, marital quality also seems to have an impact on the mental health of people in a relationship. It has been found that marital dissatisfaction is associated with anxious symptoms (Borstelmann et al., Reference Borstelmann, Rosenberg, Ruddy, Tamimi, Gelber, Schapira, Come, Borges, Morgan and Partridge2015; Proulx, Reference Proulx, Helms and Buehler2007; Trudel et al., Reference Trudel, Villeneuve, Préville, Boyer and Fréchette2010) and significantly predicts depressive symptoms (Goldfarb & Trudel, Reference Goldfarb and Trudel2019). The study of marital satisfaction in older adults may be especially important, as research has shown that spousal relationship becomes more salient to individuals throughout adulthood (Carstensen, Reference Carstensen1992), and principal relationships have significant effects on individual well-being (Giudici et al., Reference Giudici, Polettini, de Rose and Brouard2019; Scorsolini-Comin & Dos Santos, Reference Scorsolini-Comin and Dos Santos2012). In general, marital satisfaction does not decline over time (Karney & Bradbury, Reference Karney and Bradbury2020). However, Kamp Dush et al. (Reference Kamp Dush, Taylor and Kroeger2008) found in a 20-year longitudinal study that marital happiness decreases across the first years and experiences an upturn in the last years. Previous studies have also found that men report higher perceived levels of satisfaction than women (Boerner et al., Reference Boerner, Jopp, Carr, Sosinsky and Kim2014; Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Miller, Oka and Henry2014).

One potential path through which marital satisfaction may have an impact on emotional well-being is through its effects on people’s self-perceptions of aging. Several studies have shown an association between negative self-perceptions of aging and worse physical and mental health (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Bei, Gilson, Komiti, Jackson and Judd2012; Cheng, Reference Cheng2020; Lamont et al., Reference Lamont, Nelis, Quinn and Clare2017; Levy, Reference Levy2003; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Chipperfield, Perry and Weiner2012; Wurm & Benyamini, Reference Wurm and Benyamini2014). Also, negative self-perceptions of aging influence the likelihood of suffering stress (Levy et al., Reference Levy, Hausdorff, Hencke and Wei2000). Lazarus and Delonguis (Reference Lazarus and DeLongis1983) noted that beliefs about self are especially worthy of attention because they shape stress and coping over the life course. For instance, during the COVID–19 pandemic situation, higher levels of negative self-perceptions of aging longitudinally predicted higher levels of distress, irrespective of chronological age (Losada-Baltar et al., Reference Losada-Baltar, Martínez-Huertas, Jiménez-Gonzalo, Pedroso-Chaparro, Gallego-Alberto, Fernandes-Pires and Márquez-González2022). Regarding the association between marital relationships and self-perceptions of aging, being married has been linked with more positive attitudes to aging (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Bei, Gilson, Komiti, Jackson and Judd2012), and higher spousal support and lower marital strain are associated with better perceptions of aging (Barrett & Toothman, Reference Barrett and Toothman2017; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kim, Boerner and Han2018). However, to our knowledge, there is no research analyzing the specific association between marital satisfaction, self-perceptions of aging, and mental health.

Another path through which marital satisfaction may have an impact on well-being is through its stress buffering effects. Marital satisfaction has been found to buffer potential stressors such as unemployment, economic stress, somatic disease, or partner distress (Kuhn et al., Reference Kuhn, Bradbury, Nussbeck and Bodenmann2018; Randall & Bodenmann, Reference Randall and Bodenmann2017; Røsand et al., Reference Røsand, Slinning, Eberhard-Gran, Røysamb and Tambs2012). Better dyadic relationship processes are linked to the impact of external stressors (Bodenmann, Reference Bodenmann, Revenson, Kayser and Bodenmann2005; Cohan & Cole, Reference Cohan and Cole2002). For example, marital satisfaction has been found to be associated with less emotional distress in couple relationships exposed to external stressors such as economic pressure (Randall & Bodenmann, Reference Randall and Bodenmann2017) and cancer disease (Dagan et al., Reference Dagan, Sanderman, Schokker, Wiggers, Baas, van Haastert and Hagedoorn2011). These findings suggest that relationship processes may alter the impact of external stressors; partner relationship quality may thus reduce or exacerbate distress feelings related to external stress.

The COVID–19 pandemic has been a significant stressor for the whole population, and it has had a great impact on people’s mental health (Losada-Baltar et al., Reference Losada-Baltar, Jiménez-Gonzalo, Gallego-Alberto, Pedroso-Chaparro, Fernandes-Pires and Márquez-González2020; Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, McManus, Hope, Hotopf, Ford, Hatch, John, Kontopantelis, Webb, Wessely and Abel2021; Taquet et al., Reference Taquet, Luciano, Geddes and Harrison2021) and partner relationships (Balzarini et al., Reference Balzarini, Muise, Zoppolat, Di Bartolomeo, Rodrigues, Alonso-Ferres, Urganci, Debrot, Pichayayothin, Dharma, Chi, Karremans, Schoebi and Slatcher2020; Schmid et al., Reference Schmid, Wörn, Hank, Sawatzki and Walper2021). The impact of the pandemic on people’s mental health seems to have been higher in women, probably due to them being exposed to role overload, including family care (Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Hope, Ford, Hatch, Hotopf, John, Kontopantelis, Webb, Wessely, McManus and Abel2020, Wenham et al., Reference Wenham, Smith and Morgan2020). Even though no evidence of significant change in relationship quality has been found from the onset to the early stages of the pandemic (Williamson, Reference Williamson2020), some studies have found a link between stressors associated with the COVID–19 situation and partner stress and lower marital satisfaction (e.g., Reizer et al., Reference Reizer, Koslowsky and Geffen2020) and relationship quality (Randall et al., Reference Randall, Leon, Basili, Martos, Boiger, Baldi, Hocker, Kline, Masturzi, Aryeetey, Bar-Kalifa, Boon, Botella, Burke, Carnelley, Carr, Dash, Fitriana, Gaines and Chiarolanza2021).

Considering these issues, the aim of this study was to test the protective effects of marital satisfaction on middle-aged and older adults’ mental health through its effects on their self-perceptions of aging and stress associated with a critical event, such as the COVID–19 pandemic. Based on the aforementioned studies, we hypothesized that (a) marital satisfaction would be negatively associated with anxious and depressive symptomatology, (b) marital satisfaction would be inversely associated with negative self-perception of aging and levels of COVID–19-related stress, and (c) self-perception of aging and stress associated with the COVID–19 pandemic would be positively associated with anxious and depressive symptomatology. In other words, participants with higher marital satisfaction would report less negative self-perceptions of aging, and lower perceptions of stress related to the pandemic situation, which in turn would lead to less anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Method

Participants and Procedure

To be included in this study, participants had to be in a marital/partner relationship of at least one year’s duration and be at least 40 years old at the time of the data collection. Data were collected from 334 participants, 88 of whom finally did not take part in the study because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The study was therefore based on data from 246 participants, who completed the questionnaire in approximately 50 minutes (median = 49.57). As shown in Table 1, the sample was composed mostly of female participants (63%) and had a mean age of 57.87 years (SD = 10.47; range = 40–90). The average duration years of the relationship was 27.21 years (SD = 13.98; range = 1–70).

Table 1. Descriptive data and correlations among study variables

Note.

a Higher scores are related to higher level of education.

b Higher scores are related to poorer physical functioning.

c Higher scores are related to higher economic stress.

d Women.

e Participants with offspring

* p < .05;

** p < .01.

The power analysis showed that the sample size was sufficient to detect a medium effect size (f 2 = .15) (Proulx et al., Reference Proulx, Helms and Buehler2007; Whisman, Reference Whisman2007) with the target power of .80, which is adequate following Cohen’s guidelines (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988).

Data collection took place from the 15th of January to the 17th of Nov 2021. Given that social distancing rules due to the COVID–19 pandemic were still widely in force, participants were recruited and assessed through an online survey. Potential participants were contacted through social networks and all the options available to the researchers. The same request for participation was sent to associations or institutions that frequently collaborate with the research team, as well as to other potential associations or institutions contacted through social networks, such as WhatsApp, Facebook, or LinkedIn. All participants provided their consent to participate in the study, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos.

Variables and Instruments

The following sociodemographic variables were assessed: Gender, age, education level, years of married/partner relationship, and having offspring (yes/no). In addition, economic stress was measured using the question “Currently, are you worried about your financial situation?”, with answers ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (a lot).

Physical health. Physical health was assessed through the Spanish version (Alonso et al., Reference Alonso, Prieto and Anto1995) of the physical functioning subscale (10 items, e.g., “Does your health now limit you in walking more than a mile?”) of the Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF–36 scale, Brazier et al., Reference Brazier, Harper, Jones, O’cathain, Thomas, Usherwood and Westlake1992), with possible answers ranging from 1 (No, not limited at all) to 3 (Yes, limited a lot), that measures generic health-related quality of life. Cronbach’s alpha for this subscale in the present study was .85.

Marital satisfaction. Marital satisfaction was measured using the Spanish version (Castro-Díaz, Reference Castro-Díaz, Rodríguez-Gómez and Vélez-Pastrana2012) of the Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire for Older Persons (MSQFOP; Haynes et al., Reference Haynes, Floyd, Lemsky, Rogers, Winemiller, Heilman, Werle, Murphy and Cardone1992). The MSQFOP is a self-report measure that consists of 20 items (e.g., “The way affection is expressed”). The answers are presented in a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 (very unsatisfied) to 6 (very satisfied). Cronbach’s alpha in the current study suggests excellent internal consistency (.97).

Self-perception of aging. Self-perception of aging was assessed through the Attitudes Toward Own Aging subscale from Liang and Bollen (Reference Liang and Bollen1983) following the method proposed by Levy et al. (Reference Levy, Slade, Kunkel and Kasl2002). It has five items (e.g., “As you get older, you are less useful”) with a dichotomous response format (Yes or No), where higher scores indicate more negative self-perceptions of aging. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the present study was .66, similar to that found in previous studies (e.g., Losada-Baltar et al., Reference Losada-Baltar, Martínez-Huertas, Jiménez-Gonzalo, Pedroso-Chaparro, Gallego-Alberto, Fernandes-Pires and Márquez-González2022; Siebert et al., Reference Siebert, Wahl, Degen and Schröder2018).

Stress associated with the COVID–19 pandemic. As an indicator of perceived stress associated with the COVID–19 pandemic, the item “Is the situation generated by the pandemic being stressful for you?” was included, with possible answers ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (a lot).

Anxious symptomatology. Anxiety symptoms were assessed through the Spanish version (Márquez-González et al., Reference Márquez-González, Losada, Fernández-Fernández and Pachana2012) of the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory (GAI; Pachana et al., Reference Pachana, Byrne, Siddle, Koloski, Harley and Arnold2007). This scale consists of a 20-item (e.g., “I worry a lot of time”) with a dichotomous response format (Yes or No). High levels of anxious symptomatology are considered with scores higher than or equal to 9. The internal consistency or Cronbach’s alpha of the scale in the present study was .93.

Depressive symptomatology. Depressive symptoms were assessed through the Spanish version (Losada et al., Reference Losada, Villareal, Nuevo, Márquez-González, Salazar, Romero-Moreno, Carrillo and Fernández-Fernández2012) of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, Reference Radloff1977). This scale is composed of 20 items (e.g., “I felt sad”) which measure the level to which the subject manifested different depressive symptoms during the previous week. Response options consisted of a 4-point Likert- type scale with a range from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). High levels of depressive symptomatology are considered with scores higher than or equal to 16. The internal consistency o Cronbach’s alpha of the scale in the present study was .92.

Data Analysis

First, descriptive analysis and associations between the assessed variables were tested. Then, following the main objectives of the study, we tested a path analysis to determine the goodness-of-fit of the two models using IBM SPSS Amos 23 software. Sociodemographic variables (gender, age, education level, years of married/partner relationship, offspring, physical health, and economic stress) were controlled as contextual variables, and self-perception of aging and stress derived from the COVID–19 situation were proposed as significant mechanisms of action in the relationship between marital satisfaction and distress. The dependent variables were depressive symptomatology (Model 1) and anxious symptomatology (Model 2).

Only those significant associations between variables that were observed once the model was run were included in the final model. This model and its configural invariance across gender were performed. The following indices were used to assess the fit of the data from the model: Chi-square (χ2), chi-square value divided by the degrees of freedom (χ2/df) incremental fit index (IFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Indications of values under .06 (RMSEA) and over .95 (CFI and IFI) indicated excellent fit of the data to the model (Hu and Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1998). Indirect effects were analyzed following Preacher and Hayes’s (Reference Preacher and Hayes2004) recommended bootstrapping approach, using 1,000 bootstrap samples.

Results

Descriptive Data

The characteristics of the sample and the associations between the measured variables are shown in Table 1. More than half of the sample (59.8%) had university studies or higher degrees, and 66.5 % were worried about their economic situation. Most of the participants were at least a little satisfied with their partner (79.3%) and reported stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic situation (80.4%), with 38.2% reporting being quite or very stressed. High anxious symptomatology (scores over 8 on the GAI scale) was reported by 29% of the participants, and 19% had high levels of depressive symptoms (with scores over 15 on the CES-D scale).

Individuals who reported lower marital satisfaction reported higher scores in anxious and depressive symptomatology (Hypothesis 1). Individuals who reported lower marital satisfaction also reported higher negative self-perception of aging and higher levels of COVID–19-related stress scores (Hypothesis 2). Higher scores on negative self-perception of aging and stress associated with the COVID–19 pandemic were associated with higher scores in anxious and depressive symptomatology (Hypothesis 3). In addition, worse physical health was significantly related to higher levels of COVID–19-related stress, negative self-perceptions of aging, and anxiety and depressive symptoms. A higher level of education was negatively associated with anxious and depressive symptoms. Finally, female gender and higher concern about the economic situation were negatively associated with marital satisfaction and positively associated with stress related to the pandemic situation, worse self-perception of aging, and more anxious and depressive symptomatology.

Indirect Effects of Marital Satisfaction on Anxious Symptoms

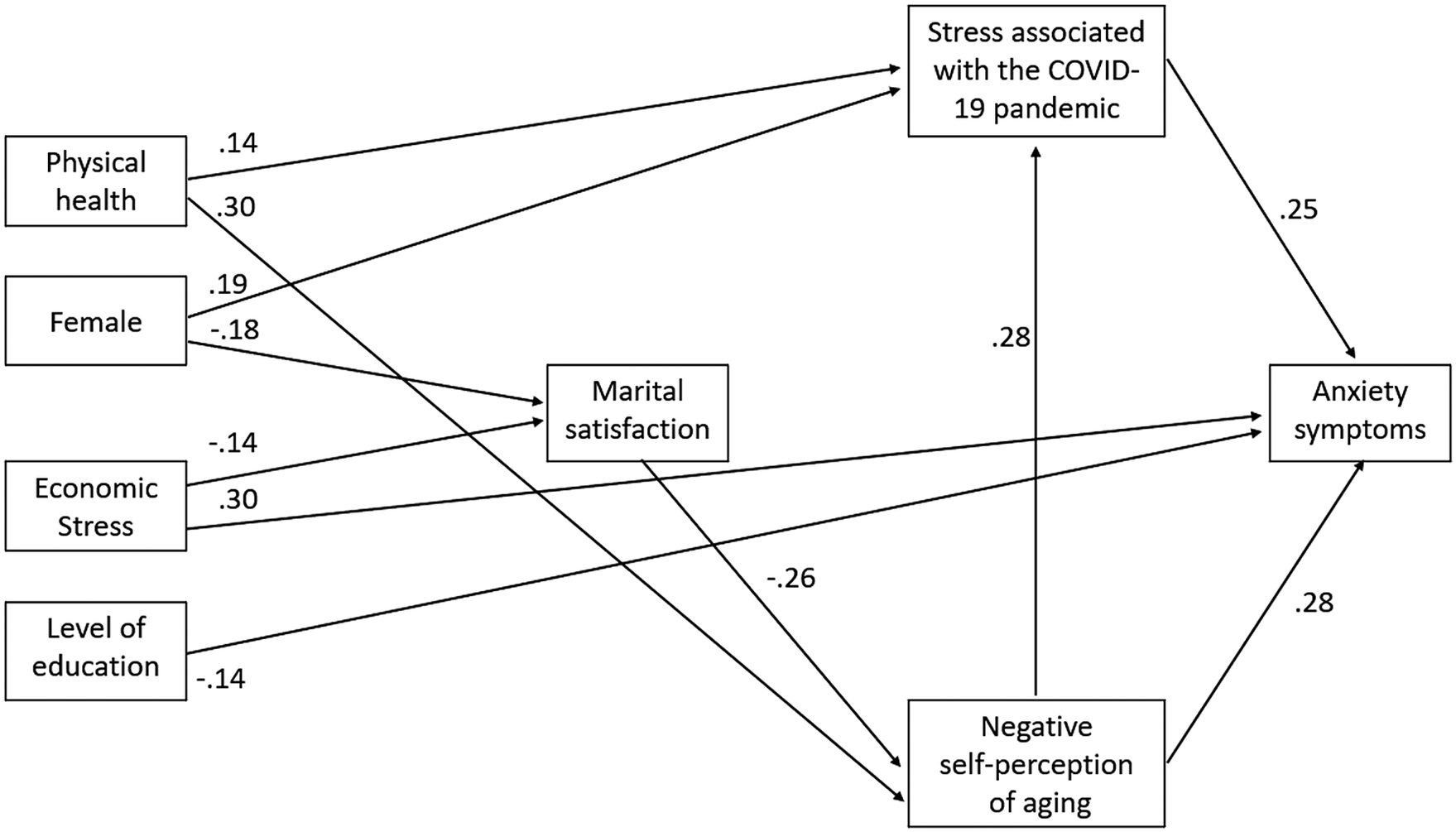

As shown in Figure 1, when all the variables were considered, lower education level, higher concern about the economy, more stress from COVID–19 situation, and negative self-perceptions of aging were directly associated with anxious symptomatology.

Figure 1. Indirect Effects of Marital Satisfaction on Anxious Symptoms.

Note. All associations are significant (p < .05). The errors have been omitted for ease of presentation.

The direct associations between gender, physical health, and marital satisfaction with anxious symptomatology, and between marital satisfaction and stress from the COVID–19 situation, which were significant in the correlational analysis, were no longer significant once all the assessed variables were considered in the model. The results of the bootstrap analysis showed that the indirect effect of marital satisfaction, standardized indirect effect = –.09; p < .01; SE = .03; 95% CI [–.16, –.05], and self-perception of aging, standardized indirect effect = .07; p < .01; SE = .025; 95% CI [.03, .13], on anxious symptomatology were statistically significant. Thus, it appears that the association of marital satisfaction with stress from the COVID–19 situation and anxious symptoms was not direct. These findings suggest that reporting lower marital satisfaction was associated with negative self-perceptions of aging, and both factors were associated with higher COVID–19 related stress. These links were significantly associated with higher scores in anxious symptomatology.

The obtained model explained 31% of anxious symptomatology. The unstandardized regression weights are shown in Supplementary Material Table 1. The obtained fit indices suggest an excellent fit of the model to the data (χ2 = 24.613; p = .10; χ2/df = 1.45; RMSEA = .042; IFI = .97 and CFI = .96). Model comparison revealed that it was plausible to assume the same structural path estimates for men and women as there was not a relevant decrease in model fit between the unconstrained model and the structural model, Δχ2(9) = 6.87, p = .65.

Indirect Effects of Marital Satisfaction on Depressive Symptoms

As shown in Figure 2, when all the variables were considered, lower education level, higher concern about the economic, lower marital satisfaction, more stress from the COVID–19 situation, and more negative self-perceptions of aging were directly associated with depressive symptomatology.

Figure 2. Indirect Effects of Marital Satisfaction on Depressive Symptoms.

Note. All associations are significant (p < .05). The errors have been omitted for ease of presentation.

The direct associations between gender and physical health with depressive symptomatology and between marital satisfaction and stress from the COVID–19 situation, which were significant in the correlational analysis, were no longer significant once all the assessed variables were considered in the model. The results of the bootstrap analysis showed that the indirect effect of marital satisfaction, standardized indirect effect = –.14; p < .01; SE = .03; 95% CI [0.21, 0.08], and self-perception of aging, standardized indirect effect = .05; p < .02; SE = .021; 95% CI [.02, .10], on depressive symptomatology were significant. Thus, it appears that the association of marital satisfaction with depressive symptoms was still significant and negative after controlling for the two proposed mechanisms of action. These findings suggest that, besides the direct effect, there is a significant indirect path. Reporting lower marital satisfaction was associated with more negative self-perception of aging, and both factors were associated with COVID–19-related stress. These links were significantly associated with higher scores in depressive symptomatology.

The obtained model explained 42% of the depressive symptomatology. The unstandardized regression weights are shown in Supplementary Material Table 2. The obtained fit indices suggest an excellent fit of the model to the data (χ2 = 26.07; p = .05; χ2/df = 1.63; RMSEA = .051; IFI = .96, and CFI = .96). Model comparison revealed that it was plausible to assume the same structural path estimates for men and women as there was not a relevant decrease in model fit between the unconstrained model and the structural model, Δχ2(10) = 6.85, p = .74.

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to analyze the association between marital satisfaction, self-perceptions of aging, stress related to the COVID–19 pandemic, and anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults over 40 years old. The study population was highly educated and worried about their economic situation. In general, participants were satisfied with their partner and reported being stressed by the pandemic situation. The average levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms were higher than for the general population in studies done prior to COVID–19 (Charles et al., Reference Charles, Mather and Carstensen2003; Gould et al., Reference Gould, Segal, Yochim, Pachana, Byrne and Beaudreau2014). Regarding the level of negative self-perception of aging, it was similar to previous studies done during the COVID–19 pandemic (Losada-Baltar et al., Reference Losada-Baltar, Jiménez-Gonzalo, Gallego-Alberto, Pedroso-Chaparro, Fernandes-Pires and Márquez-González2020), but lower than studies done prior to the pandemic (Levy et al., Reference Levy, Slade, Kunkel and Kasl2002).

Consistent with previous research (e.g., Goldfarb & Trudel, Reference Goldfarb and Trudel2019; Kamp Dush et al., Reference Kamp Dush, Taylor and Kroeger2008; Proulx et al., Reference Proulx, Helms and Buehler2007), our findings provide further support for the association between marital satisfaction and lower anxiety and depressive symptoms. In addition, this study aimed to explore paths through which marital satisfaction may influence middle-aged and older adults’ mental health. Specifically, our results suggest that the association between marital satisfaction and anxiety and depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older adults was indirect. The indirect path was through self-perceptions of aging and perceived stress (associated with the COVID–19 pandemic). The path analysis tested in the present study explained a non-negligible percentage variance of anxiety (31%) and depressive (42%) symptoms.

The obtained findings suggest that lower perceived marital satisfaction was associated with higher levels of negative self-perceptions of aging and with higher anxiety and depressive symptoms. Chronological age did not play a significant role in the explanation of mental health in the assessed models. Our findings thus suggest that self-perceptions of aging, but not age, contribute significantly to the understanding of the associations between marital satisfaction and mental health in the sample composed of middle-aged and older adults. To our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze the associations between marital satisfaction and negative self-perceptions of aging. Our findings are in line with previous research showing that close relationships contribute to understanding relevant variables for aging development. For instance, higher levels of spousal support have been found to be associated with better perceptions of aging, and spousal strain has been found to be associated with aging anxiety (Barrett & Toothman, Reference Barrett and Toothman2017; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kim, Boerner and Han2018). Likewise, our results support the widely reported association in previous studies between negative self-perceptions of aging and anxiety and depressive symptoms (e.g., Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Bei, Gilson, Komiti, Jackson and Judd2012; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Santini, Tyrovolas, Rummel-Kluge, Haro and Koyanagi2016; Levy, Reference Levy2003; Losada-Baltar et al., Reference Losada-Baltar, Jiménez-Gonzalo, Gallego-Alberto, Pedroso-Chaparro, Fernandes-Pires and Márquez-González2020; Wurm & Benyamini, Reference Wurm and Benyamini2014). In addition, previous studies indicated that couple relationships seem to be especially relevant for understanding psychological phenomena such as self-perception of aging (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Bei, Gilson, Komiti, Jackson and Judd2012; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kim, Boerner and Han2018; Mejía et al., Reference Mejía, Giasson, Smith and Gonzalez2020) and stress perception (Dagan et al., Reference Dagan, Sanderman, Schokker, Wiggers, Baas, van Haastert and Hagedoorn2011; Randall & Bodenmann, Reference Randall and Bodenmann2017). Our findings suggest that the association between marital satisfaction and anxiety and depressive symptoms may be explained by its associations with self-perceptions of aging and lower perceived stress. This link may contribute to understanding the development or worsening of mental health problems in adults over 40 years old.

Consistent with previous studies (Balzarini et al., Reference Balzarini, Muise, Zoppolat, Di Bartolomeo, Rodrigues, Alonso-Ferres, Urganci, Debrot, Pichayayothin, Dharma, Chi, Karremans, Schoebi and Slatcher2020; Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Hope, Ford, Hatch, Hotopf, John, Kontopantelis, Webb, Wessely, McManus and Abel2020; Reizer et al., Reference Reizer, Koslowsky and Geffen2020), statistically significant associations were found between marital satisfaction and stress related to the COVID–19 pandemic also associated with anxiety and depressive symptomatology. Couple dynamics and psychological distress appear to condition the association between marital satisfaction and stress related to the COVID–19 pandemic (Balzarini et al., Reference Balzarini, Muise, Zoppolat, Di Bartolomeo, Rodrigues, Alonso-Ferres, Urganci, Debrot, Pichayayothin, Dharma, Chi, Karremans, Schoebi and Slatcher2020). In the current study, the indirect effect found among marital satisfaction and mental health through the stress associated with the pandemic alone was no longer significant once the association between marital satisfaction and self-perceptions of aging was controlled for. Our findings suggest that the significant indirect effect of marital satisfaction on stress associated with the pandemic is through negative self-perceptions of aging. This significant association between negative self-perceptions of aging and higher levels of distress during the COVID–19 pandemic was also found in a longitudinal study by Losada-Baltar et al. (Reference Losada-Baltar, Martínez-Huertas, Jiménez-Gonzalo, Pedroso-Chaparro, Gallego-Alberto, Fernandes-Pires and Márquez-González2022) with a sample of 1,549 participants. Hence, it is plausible that lower marital satisfaction may lead to worse perceived mental health by increasing the chances of having negative self-perceptions of aging and perceiving more stress associated with a critical external situation such as the COVID–19 pandemic. Therefore, the obtained findings suggest that individuals who report lower marital satisfaction also report more negative self-perceptions of aging and more stress associated with the pandemic. Thus, these factors may jointly contribute to an increase in their levels of anxiety and depression symptoms. Even though women have been affected to a greater extent by the COVID–19 pandemic situation (Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Hope, Ford, Hatch, Hotopf, John, Kontopantelis, Webb, Wessely, McManus and Abel2020), the proposed model fitted well for both men and women.

This study has several limitations that need to be noted. First, the cross-sectional design does not allow causal predictions to be made between variables. The associations may have alternative directions, including the possibility that people more stressed or with higher negative self-perceptions of aging may be less satisfied with their partner (Cheng, Reference Cheng2020; Bodenmann, Reference Bodenmann, Revenson, Kayser and Bodenmann2005). Further, self-perceptions of aging and stress associated with the pandemic may generate anxious and depressive symptoms, and these may contribute to marital dissatisfaction, as suggested by other authors (Goldfarb & Trudel, Reference Goldfarb and Trudel2019; Proulx et al., Reference Proulx, Helms and Buehler2007). Longitudinal studies are needed in order to advance our knowledge regarding the causal relationships between the variables. Related to this is the limitation that prior levels of marital satisfaction and mental health conditions have not been controlled for.

In addition, participants were a convenience sample consisting of middle-aged and older adult volunteers who were recruited by social media, so only individuals who manage new technologies properly could complete the questionnaire. The sample may therefore not be representative of the general sample of middle-aged people and, more specifically, older adults. Even though the use of single-items for measuring the stress associated with the COVID–19 pandemic may be considered a limitation, there are studies that provide support for the use of single-items in surveys and even clinical contexts (e.g., Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Ruggero, Chelminski, Young, Posternak, Friedman, Boerescu and Attiullah2006). Moreover, it should be noted that, although not all the individuals evaluated were older adults, the GAI was used in order to avoid biases in the measurement of anxiety in older adults (Pachana et al., Reference Pachana, Byrne, Siddle, Koloski, Harley and Arnold2007).

Finally, although several known variables associated with depression and anxiety among partners were measured in this study, other relevant variables have not been measured. For example, neuroticism and sense of mastery have been previously found to be associated with marital satisfaction (Claxton et al., Reference Claxton, O’Rourke, Smith and DeLongis2012; Huber et al., Reference Huber, Navarro, Womble and Mumme2010), self-perceptions of aging (Jang et al., Reference Jang, Poon, Kim and Shin2004), and perception of stressful situations (Abbasi, Reference Abbasi2016; Jang et al., Reference Jang, Poon, Kim and Shin2004).

Despite the above-mentioned limitations, the present study is the first to analyze the joint effects of marital satisfaction, self-perceptions of aging, and stress associated with facing a critical stressful situation (the COVID–19 pandemic).

Marital satisfaction seems to be especially relevant for understanding the association of individuals’ self-perceptions of aging and stress associated with the pandemic on anxious and depressive feelings. Quality of communication, spousal support or shared leisure are factors of marital satisfaction that may be relevant to assess as they play a significant role in reducing anxiety and depression symptomatology. Our findings suggest that marital satisfaction may be an important variable for understanding why people have negative self-perceptions of aging. Marital satisfaction may be considered a source for both emotional and problem-solving support, buffering the impact of negative life events and psychological distress that may prompt the embodiment of negative self-perception of aging. Thus, prevention of marital dissatisfaction or targeting this variable in interventions focused on reducing negative self-perceptions of aging (Laidlaw & Kishita, Reference Laidlaw and Kishita2015; Laidlaw & McAlpine, Reference Laidlaw and McAlpine2008) may contribute buffering the effects of stressors that people face, increasing their well-being.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/SJP.2023.13.