How does an ascendant political party attain the status of a party regime? It is generally accepted that the Jacksonian Democrats, the post–Civil War Republicans, the New Deal–era Democrats, and (arguably) the Reagan-era Republicans each developed and entrenched a governing vision that shaped the political landscape for decades to come. But regime entrenchment, while obvious in retrospect, is not foreordained. In their early years, each of the abovementioned regimes faced vigorous opposition from actors who sought to undo their initial achievements. In each case, there were moments when a return to partisan parity, or even the collapse of the ascendant party's coalition, was within the realm of possibility. Why did these ascendant parties succeed in entrenching a coherent policy vision, while others—for example, the Obama-era Democrats—did not?

Most existing studies of regime entrenchment focus on the internal dynamics of the ascendant party and the strategic decisions of its leaders. But there are reasons to doubt that these factors alone can account for the success or failure of regime-building projects. First, a single-minded focus on the ascendant party tends to obscure the fact that this party exists within a broader party system. The opposing party, in other words, also has a say in the fate of the nascent party regime. Although not in a position to dictate outcomes, its internal dynamics and decision-making will inevitably shape the landscape on which partisan conflict plays out. If a significant faction within the opposing party favors accommodation of the ascendant party's agenda, for example, regime entrenchment will be more likely to occur. Conversely, entrenchment may be less likely, though by no means impossible, when the opposition party is monolithic in rejecting the ascendant party's governing vision.

A second gap in the literature concerns the role of nonpartisan actors in legitimating regime principles. Existing studies of party regime formation—and of party ideology more broadly—tend to examine civil society groups such as unions, churches, and advocacy organizations only in their capacity as members or potential members of party coalitions. But such groups are arguably more useful for establishing the legitimacy of regime principles precisely when they are not members (or potential members) of the ascendant party coalition. Stated differently, when it comes to winning over doubters in the electorate (or in government), formally nonpartisan organizations with claims to expertise over particular issue areas may be more effective than groups with obvious ties to the dominant party. If the goal of the regime-building project is to elevate a party's programmatic commitments above the fray of “ordinary” politics, organizations that can themselves credibly claim to be above the political fray are likely to be particularly helpful in this endeavor.

These points might be illustrated with any number of examples from past regime-building projects. In what follows, I focus on a critical juncture in the development of the New Deal–era Democratic regime—namely, the period from the late 1940s to the mid-1950s when a resurgent Republican party briefly threatened the Democrats’ bid for regime entrenchment. That the Democratic regime survived this challenge, I shall argue, was due less to the genius of its leaders or the cohesiveness of their coalition than to Republican moderates’ successful discrediting of their conservative rivals. As we shall see, Republican moderates used their influence within influential civil society groups to frame the New Deal's legacy in positive terms—and hence to paint conservatives’ attempts to eviscerate it as ideologically extreme and contrary to American values. Even as they worked to roll back programs they viewed as wasteful or ineffective, GOP moderates successfully defended the nascent social welfare state that was the New Deal's most important legacy, and in so doing, they effectively secured the Democratic regime's entrenchment.

The article focuses on two civil society groups in particular: the National Council of Churches (NCC) and its economic policy arm, the Department of the Church and Economic Life (DCEL). Representing Protestant denominations with a combined membership of about 35 million, the NCC was the nation's largest ecumenical body during the 1950s and 1960s. Although it did not endorse candidates for public office, its pronouncements on social and economic issues were widely covered in the media and its representatives testified frequently before Congress. Hence, both moderate and conservative Republicans viewed the NCC as a critical site of contestation in Eisenhower-era debates over economic policy. At a moment when the two factions were battling for control within the administration, each hoped that favorable pronouncements from the nation's largest ecumenical body would tip the scales in its favor. In the end, Republican moderates—several of whom were simultaneously serving in the Eisenhower administration—joined forces with left-leaning labor leaders, academics, and clergymen to gain effective control over the NCC's economic policy arm, which they used to issue pronouncements declaring the welfare state an authentic outgrowth of Protestant social teachings. The result was to discredit (for the time being) the laissez-faire economic philosophy of the Republican right while simultaneously creating the appearance, at least, of a broad-based Protestant consensus in favor of preserving the core of the New Deal.

1. Rethinking the Dynamics of Regime Entrenchment

Scholars have long found it useful to view American political development through the lens of party regimes. A reasonable synthesis of regime theories goes as follows: A party regime comes into being when a political party, typically powered by a novel governing coalition, establishes electoral dominance over its rival(s). Armed with control of the White House and substantial majorities in Congress, the ascendant party writes its favored policies into law. Moreover, assuming its governing vision is validated at the ballot box, the party will also establish effective control over the terms of political debate. Even critics must now formulate their arguments using the regime's ideas and terminology, lest they be seen as defying the will of the voters. And yet, periods of one-party dominance do not last forever. Over time, the coalition underpinning the regime begins to fracture, typically because of the introduction of novel or cross-cutting issues (e.g., slavery in the 1850s) or the arrival of a crisis that proves beyond the regime's ability to manage (e.g., the Great Depression). The splintering of the regime's governing coalition, combined with the apparent discrediting of its policy vision, creates an opportunity for the out-of-power party to augment its own coalition and to articulate an alternative set of principled commitments. In time, the voters validate the opposition party's critique, the old regime is driven from power, and the cycle repeats.Footnote 1

The party regime perspective undoubtedly provides a useful heuristic for thinking about the possibilities and limits of political action in specific historical periods. However, some of its core features remain undertheorized and poorly understood—for example, the process of regime entrenchment. By this, I mean the process through which the ascendant party consolidates effective control of both public policy and public discourse, so that its programmatic commitments come to be viewed as normatively binding by most actors within the political system.Footnote 2 To be clear, entrenchment does not mean the end of debates over policy or ideology. Rather, it means that the burden of proof shifts from the ascendant party to its critics, who must now explain why their objections to the ascendant party's program should not be dismissed out of hand.

To date, research on regime entrenchment has tended to focus on the electoral record and internal dynamics of the ascendant party. That is to say, the question of whether an ascendant party will succeed in establishing itself as a regime is usually said to depend on (1) the length of time in which the ascendant party enjoys an overwhelming advantage at the ballot box, (2) the overall cohesiveness of the ascendant party's coalition, and (3) the strategic choices made by the ascendant party's leaders.Footnote 3 Given a decade or more of electoral dominance, a cohesive party coalition, and leaders who are skilled at exploiting the mistakes of the opposition, the ascendant party will on this view be well positioned to establish itself as a durable regime. Under these conditions, it can, for example, staff the judiciary and federal agencies with appointees who share the party's vision and who will reliably perpetuate its ideological commitments for decades to come.Footnote 4 Similarly, a series of convincing electoral victories, such as those enjoyed at the presidential level by Republicans between 1860 and 1880, or the Democrats between 1932 and 1948, may tend to elevate the ascendant party's ideology above the level of ordinary partisanship, making it more akin to a national creed.Footnote 5

But while sustained electoral dominance and (relative) party cohesiveness are necessary conditions for regime entrenchment, they are not sufficient conditions. Stated otherwise, even relatively cohesive parties are unlikely to fully consolidate control of either public discourse or public policy during the (inevitably brief) period of electoral dominance. There are several reasons for this. First, because the reconstructive phase entails the formation of a novel governing coalition, this period will tend to be one in which the ascendant party's long-term program has yet to be fully articulated. Major objectives (e.g., halting the territorial expansion of slavery, constructing a social safety net) may be clear, but the details will remain to be fleshed out in debates between the party's constituent factions.Footnote 6 For the same reason, the ideological commitments that will eventually undergird and synthesize the ascendant party's policy objectives may be inchoate during the reconstructive period.Footnote 7 Much energy will also need to be directed toward remaking internal party institutions that were constructed prior to the emergence of the new governing coalition, and which may actively hinder the party's programmatic efforts until reformed.Footnote 8 Entrenchment is unlikely to occur until these tasks of internal party governance have been completed.

Moreover, even if the ascendant party manages to quickly coalesce around a set of ideological and policy commitments, the window of time in which it can unilaterally implement these commitments is usually very short. The reconstructive phase is—again by definition—one in which the ascendant party enjoys overwhelming electoral success, typically resulting in effective one-party control of the federal government. But while this period of one-party rule may allow for the passage of transformative legislation, as well as transformative judicial and executive branch appointments, it will typically be too brief to ensure the entrenchment of the ascendant party's programmatic commitments. Assuming the opposition party returns to electoral competitiveness within a decade or so of its initial defeat, large portions of the judiciary and bureaucracy will continue to be staffed by holdovers from the old regime.Footnote 9 The question, then, is not whether the ascendant party can reshape the policy agenda while the opposition party is at its weakest, but whether it can reinforce and expand upon its initial successes once the opposition party has regained its footing.

Taken together, these observations suggest that the critical moment when the question of regime consolidation hangs in the balance will tend to occur not during the reconstructive phase but during what might be termed the “first preemption”—that is, the moment when the opposition party begins once again to enjoy success at the ballot box, typically meaning it has recaptured control of Congress or the executive branch (or both). Scholarly work on this phase of the regime cycle is scant, however, and existing studies mostly focus on the narrow question of how “preemptive” presidents, such as Woodrow Wilson and Dwight D. Eisenhower, have dealt with the challenges of executive leadership at a time when the opposition party's program enjoys widespread approval.Footnote 10 Such studies are important for what they reveal about the opportunities and limitations of presidential leadership in such periods. And yet, because the ideological dominance of the ascendant party is typically taken for granted, we learn little about the dynamics that shape ideological development in such periods. Without a better understanding of these dynamics, it is impossible to say why ascendant parties sometimes succeed in entrenching their programmatic commitments, and why, on the other hand, they sometimes fail in their attempts to remake the political landscape.

Three specific features of the preemptive political landscape deserve more attention than they have previously received. First, a glance at the historical record suggests that the opposition party's return from exile will tend to trigger a shift in public discourse, which the ascendant party and its supporters must successfully navigate in order to ensure regime consolidation. As the crisis (or crises) that brought down the old order fades from view, and as the ascendant party begins to confront (comparatively minor) crises and scandals of its own, discursive space is opened for a reconsideration of the new regime's most ambitious agenda items. In this changed environment, group-based, us-versus-them appeals, which are often effective in the reconstructive phase, may become a liability.Footnote 11 Indeed, the opposition party's return to electoral competitiveness will often be powered by allegations that the ascendant party, having seized the levers of power, is using its influence to enrich favored interest groups at the expense of the common good. (Examples include the Democrats’ demonization of the Reconstruction agencies in the 1870s and the Republicans’ focus on labor union corruption in the late 1940s and early 1950s.)Footnote 12 In the face of such allegations, regime supporters will often find it necessary to recast in universal terms policies that were initially conceived as providing group-specific benefits. The party's programmatic commitments, it will now be said, are not sops to coalition members but rather straightforward embodiments of broadly shared national values.Footnote 13

Second, the success or failure of the ascendant party's efforts to entrench its ideas and policies will likely depend, to a greater extent than is usually recognized, on the intraparty dynamics of the opposition. Typically, the experience of spending several years in the electoral wilderness will fracture the opposing party into what might be termed cooperative and intransigent factions.Footnote 14 The cooperative faction, recognizing the changed electoral environment, will be open to compromise with the ascendent party. The intransigent faction, whether motivated by principle or by a contrasting set of strategic calculations, will instead work to discredit the ascendant party's ideas and frustrate its policy objectives at every turn. The emergence of this divide represents a moment of contingency in the party regime cycle. If actors affiliated with the ascendant party can successfully intervene in the intraparty struggle of their opponents—whether by forming durable linkages with the cooperative faction or by ensuring the marginalization of the intransigent faction—they are likely to succeed in consolidating power. If they cannot, and if the intransigent faction seizes control of the opposition party machinery, then consolidation becomes less likely, as the opposition party will use the many veto points provided by the constitutional system to thwart the ascendant regime's bid for consolidation.

Finally, there are good reasons to believe that ostensibly nonpartisan actors, including civil society organizations, play a larger role in the process of regime entrenchment—and in the shaping of party ideology more generally—than is usually recognized.Footnote 15 Such groups may, for example, provide a backchannel for the creation of the informal cross-party alliances that are (or so I shall argue) a virtual precondition for successful entrenchment.Footnote 16 Moreover, civil society organizations may be better positioned than explicitly partisan actors to vouch for the legitimacy and public-spiritedness of the ascendant party's program as it faces renewed attacks from the opposition. Core party constituency groups will, of course, argue that attempts to reverse the regime's early achievements are contrary to the public good. And yet the obviously self-interested nature of such claims will render them suspect in the eyes of the electorate. Nonpartisan civil society groups that lack obvious ties to the ascendant party are more likely to be successful in this regard. Favorable pronouncements from such groups can, at least in theory, elevate the regime's core policy commitments above the tumult of ordinary political debate, recasting them as authentic embodiments of broadly shared societal values.

Religious groups may be particularly well suited to the abovementioned tasks. Although largely ignored in the existing party regime literature, religious elites—particularly those associated with the nation's large, “mainline” Protestant denominations—have historically ranked among the most important arbiters of social and political conflicts.Footnote 17 In order to obtain an accurate picture of the processes through which regime formation has historically occurred, it is important to recover the role of religious groups in vouching for—and sometimes contesting—the programmatic aims of ascendant political parties.

2. Mainline Protestants, Economic Policy, and the Party System, 1932–1947

The nation's mainline Protestant churches are rarely mentioned in historical accounts of the Democratic Party regime that lasted from the New Deal through the 1970s, and for a seemingly good reason: Their members leaned Republican. Indeed, mainline denominations such as the Episcopalians and Presbyterians, with their comparatively wealthy memberships, were virtually synonymous with fiscally conservative, socially moderate “country club” Republicanism. (Hence, the popular description of the Episcopal Church as “the Republican party at prayer.”)Footnote 18 Geographically, the mainline denominations were concentrated in the Northeast and Upper Midwest, both traditional Republican strongholds (though many states in these regions were competitive during the New Deal period).Footnote 19 Moreover, the mainline was largely white and, more specifically, WASP-dominated. If the New Deal Democratic coalition in its early years is typically understood as an alliance of working-class Catholics, Jews, “white ethnics,” and white Southerners, then the mainline was its antithesis: middle and upper class, Protestant, and descended from the Puritans.

And yet, a single-minded focus on party registration risks obscuring the extent to which the New Deal regime's programmatic commitments were rooted in the social teachings of the mainline Protestant churches. The mainline economic vision, which took shape in the years around 1910, was an outgrowth of the theological tradition known as the Social Gospel. Embodied in institutions like the Federal Council of Churches (FCC) and in documents like the “Social Creed of the Churches”—adopted in 1908 at the inaugural meeting of the FCC—the Social Gospel's most important innovation was to link the saving of souls to the regeneration of society.Footnote 20 Middle- and upper-class Protestant churchgoers were no longer to content themselves with praying for the lower classes. Rather, God insisted that they prepare the way for his Kingdom by addressing the systemic roots of human suffering, which meant, among other things, enacting old-age pensions, unemployment insurance, and the living wage.Footnote 21

To implement this vision, the FCC, an umbrella organization representing the nation's largest non-Southern Protestant denominations, formed an industrial department whose leaders generally aligned themselves with organized labor in the struggle to advance state oversight of industry. At roughly the same time, several Protestant denominations, including Congregationalists, Disciples of Christ, Episcopalians, Methodists, and Presbyterians, formed social service agencies or committees and tasked them with formulating policy recommendations on economic matters.Footnote 22 Although the denominational social service agencies did not always march in lock step with the FCC, the new groups shared a conviction that aggressive state action was needed to relieve the suffering of industrial workers, who might otherwise spurn organized religion altogether.Footnote 23

During the 1910s and early 1920s, the FCC and other mainline agencies joined forces with an array of progressive membership groups—from the National Child Labor Committee to the General Federation of Women's Clubs—to press the case for protective labor legislation.Footnote 24 And like most of their secular allies, mainline religious reformers enjoyed somewhat closer ties to the Republicans than the Democrats. (Teddy Roosevelt, who counted the Social Gospel theologians Washington Gladden and Walter Rauschenbusch as inspirations, was a particular favorite of church leaders.)Footnote 25 This changed during the Depression years, however, when President Herbert Hoover's reluctance to support fundamental economic reforms pushed mainline leaders towards the Democratic camp. Although usually careful to avoid overt endorsements of the party or its candidates, most mainline agencies found ways to subtly signal their preference for Franklin Roosevelt in the 1932 election.Footnote 26 Roosevelt, an active Episcopalian, was grateful for the churches’ support, which he found particularly helpful in rebutting charges that his economic program was inspired by Bolshevism. On the campaign trail, he regularly quoted from the FCC's economic pronouncements; and in 1933, after winning the presidency, he addressed the organization's twenty-firth anniversary gathering, where he delivered a speech steeped in the language of the Social Gospel.Footnote 27

As FDR set about implementing his transformative economic agenda, church leaders threw themselves into the task of mobilizing public support for the New Deal. James Myers, who headed the FCC's industrial department, organized church-based letter-writing campaigns on behalf of the National Recovery Act (NRA), the Social Security Act, and the National Labor Relations Act.Footnote 28 Several FCC member denominations, including the Methodists, Northern Presbyterians, Episcopalians, and Disciples of Christ, publicly endorsed the creation of unemployment insurance programs and old-age and disability pensions.Footnote 29 Numerous Protestant churches throughout the Northeast and Midwest organized “NRA Sundays” to educate churchgoers on the president's recovery program. And on the West Coast, hundreds of churches formed “Golden Rule Armies,” whose members pledged to uphold the NRA's wage and price codes in their personal and professional lives.Footnote 30

The mainline churches’ relationship to the party system evolved again in the immediate postwar years—this time due to the emergence of fissures in the New Deal coalition and the subsequent resurgence of the GOP's conservative wing. The first signs of weakness in the Democratic coalition appeared in the late 1930s when Southern Democrats, sensing that a resurgent labor movement posed a threat to racial segregation, began to defect on labor issues.Footnote 31 New problems emerged in the mid-1940s, including the massive and generally unpopular strike wave of 1946, alarming shortages of meat and other foodstuffs, and credible accusations of corruption in the labor movement. These developments emboldened the GOP's staunchly anti–New Deal conservative wing, which had been marginalized during the World War II years due to its isolationist foreign policy leanings. When Republicans captured unified control of Congress in the 1946 midterms, the conservative wing, led by Ohio Senator Robert A. Taft and backed by a supporting cast of deep-pocketed business groups, including the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, immediately set to work rolling back labor-organizing protections. The result was the Taft-Hartley Act, which became law in 1947 after a Republican-controlled Congress overrode President Harry Truman's veto.Footnote 32 Democrats could take some comfort in the fact that Truman was narrowly reelected in 1948, but even this positive development was marked by ill omens. Many white Southerners, outraged by the national party's adoption of a civil rights plank, defected to Strom Thurmond's “Dixiecrat” presidential bid, while a smaller leftist faction, disturbed by Truman's hardline stance towards the Soviet Union, backed former Vice President Henry Wallace's campaign.

Not coincidentally, the FCC and other mainline agencies faced increasing external pressures at the precise moment that the Democratic coalition seemed to be in danger of fracturing. During the 1940s, allegations of communist infiltration dogged both the FCC and the denominational social service agencies (and the labor unions with which they were closely aligned), leading to a catastrophic loss of funding and, in some cases, the severing of ties between agencies and their parent denominations.Footnote 33 The FCC suffered a further blow when a group of politically and theologically conservative clergymen formed the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE), an ecumenical group created to contest the FCC's claim to be the sole, or at least primary, voice of American Protestantism. Founded in 1942, the NAE did not immediately succeed in driving a wedge between the large Protestant denominations and the FCC, but its widely publicized attacks on the FCC—which frequently amplified the Red-baiting propaganda of the political right—caused further damage to its rival's reputation.Footnote 34

In response to these developments, mainline leaders launched a major restructuring initiative in the years around 1947. The effort, which was made possible by a sudden postwar uptick in church attendance and donations, proceeded on several fronts simultaneously, but its unifying goals were to (1) increase lay representation in the governing bodies of the major mainline agencies and (2) to improve the financial health of said agencies. In the case of the FCC, the entire organization was folded, along with a handful of formerly independent organizations, into a new umbrella group known as the National Council of Churches (NCC).Footnote 35 Formally launched at the end of 1950, the NCC represented twenty-nine Protestant denominations—essentially all of the nation's largest denominations, minus the Southern Baptists—and around 35 million church members.Footnote 36 In contrast to the FCC, whose leadership was dominated by clergymen, the NCC would be governed by a general board whose 250 seats were roughly equally divided between church officials and lay people. In addition, its officers, including its president, were elected at triennial general assemblies whose delegates were selected by the member denominations.

Also in contrast to the FCC, the NCC was immediately flush with cash. Its initial operating budget was approximately $8 million (or $86 million in 2022 dollars). Member denominations covered around half this amount, while donations from individuals, foundations, and corporations, as well as payments for services rendered (including royalties), made up the rest. Top executives from Armco Steel, Beech Aircraft, General Mills, General Foods, Firestone Tire and Rubber, Chrysler, Sun Oil, and Cummins Engine headed the organization's initial fundraising drive. The resulting contributions were channeled into one of eight program areas, including evangelistic programs ($2 million), overseas relief work and refugee programs ($1.9 million), and domestic economic relief work ($1.4 million). Initially, only about $330,000 was dedicated to programs that would “apply Christian principles” to politics and society, but this amount would soon be supplemented by major grants from the Rockefeller Foundation and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO).Footnote 37

In addition to the founding of the NCC, two other initiatives proved crucial to restoring the ecumenical movement's lost influence and prestige. First, mainline leaders in the late 1940s launched a major expansion of the local church council network. The local church council—a professionally staffed organization representing (in theory) all the Protestant churches in a given state or city—performed a range of tasks, from coordinating evangelistic campaigns to advocating on behalf of legislation. In the prewar period, such councils existed only in a handful of large cities, but their numbers exploded in the immediate postwar period when the FCC (and later NCC) began providing logistical assistance to encourage their formation.Footnote 38 Between 1943 and 1953, the number of professionally staffed state and local church councils more than doubled, increasing from about eighty to more than two hundred. (See Figure 1 below.) The result was the birth of a critical communications network that allowed the NCC and other national Protestant agencies to disseminate policy-focused information in a timely fashion to even the most remote areas of the country (with the exception of the South, whose white religious leaders mostly spurned the church council movement).Footnote 39

Figure 1. Growth of Protestant Church Council Network, 1943–1953.

Sources: Data on council locations compiled from Benson Y. Landis, ed., Yearbook of American Churches (Lebanon, PA: Sowers Printing, 1943); Yearbook of American Churches (New York: National Council of Churches, 1953).

Second, several of the largest Protestant denominations opened policy-focused Washington, DC, offices—as did the NCC. Although most denominations had created “social service” committees or departments in the 1910s, few of these were directly represented in the nation's capital. Between 1943 and 1948, however, at least six large Protestant denominations launched professionally staffed DC offices. (The NCC opened its Washington office at the time of its founding in 1950.) Typically led by clergymen who were also registered lobbyists, the denominational offices tracked the progress of legislation, advocated on behalf of denomination-supported policies, and dispatched representatives to testify before congressional committees. Although policy stances varied somewhat across denominations, the emergent “church lobby” was generally supportive of the postwar Democratic regime's programmatic commitments, including boosting funding for foreign aid, social welfare programs, and public education.Footnote 40

3. The Founding of the Department of the Church and Economic Life (DCEL)

During the waning years of the Truman administration, the question of what, if anything, the newly formed NCC should say about economic matters was particularly pressing. Unsurprisingly, some of the NCC's founding donors, including the arch-conservative Sun Oil heir, J. Howard Pew, hoped to create an ecumenical body that would advocate for libertarian economic policies and adopt a hard line on communism—or, failing that, an organization that would focus on evangelistic efforts and avoid politics altogether.Footnote 41 That this did not come to pass was due to the efforts of two men: Charles P. Taft and Cameron Hall. Taft, the brother of Senate Republican Leader Robert Taft, was a card-carrying member of the Republican party's moderate wing—a fact that frequently caused tensions between the siblings.Footnote 42 In 1947, during the early stages of the FCC's rebranding effort, he accepted the presidency of the ecumenical organization, becoming the first lay person to hold this position. Shortly thereafter he joined forces with Hall, a Presbyterian minister who had succeeded James Myers as head of the FCC's industrial department, to transform the organization's economic policy arm.

Although the two men were not always of one mind—Hall was an ardent New Dealer with close ties to organized labor, while Taft was sympathetic to complaints that the FCC's pro-labor activism had robbed it of credibility—they agreed that the group's economic department was ill-served by the preponderance of theologians and clergymen in its ranks. If the goal was to influence policymakers, then the FCC should staff the department with lay people who were active in economic affairs.Footnote 43 If a group of genuinely influential business and labor leaders could be brought together under the council's auspices, Taft and Hall believed, the group might come to be seen as the unofficial “voice of Protestantism on economic life issues,” performing a function akin to that of papal encyclicals for Roman Catholics.Footnote 44

Remarkably, events unfolded almost exactly as Taft and Hall predicted. Working closely with Rockefeller Foundation president Chester I. Barnard and Studebaker CEO (and later Ford Foundation president) Paul G. Hoffman, the pair fashioned a 125-person organization called the Department of the Church and Economic Life (DCEL). At the official launch of the NCC in late 1950, the DCEL was designated to serve as the NCC's economic policy arm, with Taft as chairman and Hall as executive director. The DCEL's members were equally divided between representatives of business, labor, agriculture, government, the ministry, and the academy. All were nominally Protestant, and each denomination was represented roughly in proportion to its share of the NCC's total membership. More to the point, the group's members were among the most important players in their respective spheres. They were executives from General Electric, General Foods, Goodrich, Standard Oil, Cummins Engine, and other corporations; labor leaders including CIO president Walter Reuther and AFL research director Boris Shishkin; and academics such as the economist Kenneth Boulding and the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. Members from the world of politics included Taft (the 1952 GOP nominee for governor of Ohio), Senator Paul Douglas (D-IL), Roy Blough of the White House Council of Economic Advisors, and Charles T. Douds of the National Labor Relations Board. In addition, Arthur Flemming, who filled several high-level posts in the Truman and Eisenhower administrations, worked closely with the DCEL while serving as the NCC's vice president with responsibility for social and economic programs. (Table 1 displays a partial list of the DCEL's members.)

Table 1. Selected Members of the Department of the Church and Economic Life (DCEL)

() = Number of meetings attended between January 1951and April 1953 (out of eight total meetings)

Source: Department of the Church and Economic Life, “Study of Attendance at Eight Meetings,” National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America Records, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, PA, RG4, box 1, folder 21.

From January 1951 through the early 1960s, the DCEL's members met in New York three times a year for the purpose of formulating policy statements; commissioning academic studies; and planning educational programs for businesses, unions, and local congregations. The group was afforded a surprising degree of autonomy. NCC leaders allowed it to publish books, pamphlets, and other “study materials” with little oversight from the NCC's board or executive officers. Formal policy pronouncements were another matter, however. Once approved by the DCEL, they were forwarded to the NCC's general board, which possessed ultimate authority to speak for the NCC. Although board approval was usually a formality, it was necessary for pronouncements to become part of the NCC's official platform—and thus to validate the DCEL's claim to be the economic “voice” of Protestantism writ large.Footnote 45

For the first year and a half of its existence, the DCEL generated few headlines. It debated draft statements on inflation and work stoppages in the defense industry, but negotiations over the precise wording of these pronouncements dragged on for months with little progress.Footnote 46 That the DCEL was relatively quiet in 1951 and early 1952 was likely because the group's business members, who were mostly moderate Republicans, were reluctant to sign onto left-leaning policy statements at a time when the incumbent Democratic president's approval ratings were in freefall. Although many DCEL members, including Taft, Walter Williams, and Paul G. Hoffman, privately supported many aspects of the New Deal and Fair Deal, they were also deeply invested in the success of Eisenhower's presidential campaign. Williams and Hoffman, in fact, led the Citizens for Eisenhower organization, and they had little incentive to push back against attacks on the post–New Deal welfare state when such arguments seemed to be resonating with the public.Footnote 47

In the fall of 1952, however, two developments altered the strategic incentives facing the DCEL's moderate business representatives. First, the GOP takeover of Congress and the presidency initiated an intraparty struggle between the Robert Taft–led conservative wing of the Republican Party, which was committed to weakening the welfare state and labor-organizing rights, and the party's moderate wing, which viewed the welfare state and (a modicum of) labor-organizing protections as essential to continued economic prosperity.Footnote 48 With conservatives in the administration and Congress now in a position to act on their policy priorities, the question of whether the welfare state was consistent with “Christian” or “American” values was no longer rhetorical; to remain silent was now to aid conservatives and their interest group allies in their bid to roll back the New Deal.

Second, and relatedly, a group of conservative Republican businessmen led by J. Howard Pew launched a campaign to curtail the DCEL's influence within the bureaucratic structure of the NCC. Specifically, Pew won approval from the NCC leadership to form a National Lay Committee whose ostensible purpose was to serve as a link between the NCC bureaucracy and rank-and-file Protestant churchgoers. He then staffed the new organization with a group of right-leaning executives and labor leaders and began using it as a bludgeon against the DCEL.Footnote 49 What lay people most wanted, according to Pew and his allies on the Lay Committee, was for left-leaning religious bodies to stop issuing policy pronouncements on economic questions. If the NCC did not heed this advice, he warned, then the Lay Committee's members would cease their financial support of the NCC.Footnote 50

The combined effect of the Republican sweep and Pew's bullying behavior was to drive the DCEL's moderates into a fragile alliance with its left-leaning academics, ministers, and labor leaders. Although none of the parties fully trusted the motives of the others, each agreed that cooperation was necessary to prevent Pew from hijacking the NCC bureaucracy for his own purposes—and also to prevent a conservative victory in the wider struggle for control of the Eisenhower administration's economic agenda. The group's October 1952 meeting thus marked the beginning of a two-year period of intense activity during which the DCEL emerged as a major voice in opposition to the GOP's conservative wing and its efforts to roll back core components of the New Deal and Fair Deal.

4. Reframing the Welfare State: The DCEL's Major Initiatives, 1953–1954

During the early years of the Eisenhower presidency, the DCEL's members channeled their energies into three separate initiatives. The first, which culminated in late summer 1954, centered on drafting a formal statement of economic principles that would put the NCC on record as opposing cuts to the welfare state and attempts to further weaken labor-organizing rights. The second was a series of popular books, published between the spring of 1953 and the summer of 1954, that laid out moral, religious, and social scientific arguments for a strong welfare state and robust but “responsible” unions. The third was the annual Labor Sunday message, released annually in early September, which distilled the group's theological arguments and policy recommendations down to their essence with the aim of disseminating them to the widest possible audience.

In each case, the major challenge was to develop a compelling rebuttal to the increasingly popular claim that the policy achievements of the New Deal and Fair Deal years were way stations on the road to communism. The allegation was as at least old as the 1932 campaign, but it gained new purchase in the postwar years thanks to the increased salience of the communist threat, both at home and abroad. As early as 1943, Friedrich Hayek had scored a runaway bestseller with The Road to Serfdom, which posited a slippery slope from liberal social welfare programs to Soviet-style totalitarianism. Hayek's postwar admirers pushed his argument to its logical conclusion, claiming that Truman's Fair Deal, with its promises of universal health insurance and other expanded social welfare programs, marked the point of no return for American capitalism. As former President Hoover put the point in a much-publicized 1949 speech, Democrats were “blissfully driving [the nation] down the back road” to collectivism by way of “the welfare state”—a label that was merely “a disguise for the totalitarian state by the route of [government] spending.”Footnote 51 Hoover's message was amplified by NAM and other conservative interest groups, who undertook a major investment in book and magazine publishing for the purpose of convincing Americans that social welfare programs were, by definition, incompatible with individual initiative and freedom.Footnote 52

In response to this line of attack, many liberal supporters of the New Deal ceased defending the welfare state in terms of class interests—a framing that seemed to confirm the charge of creeping communism—and began instead to describe it as a guarantor of social stability and a bulwark against totalitarianism. The book usually credited with initiating this shift is Arthur Schlesinger Jr.'s 1949 bestseller, The Vital Center.Footnote 53 But Schlesinger's argument was not original. Rather, it was inspired by the insights of his friend—and DCEL member—Reinhold Niebuhr, who had earlier built a pragmatic but theologically grounded case for the liberal democratic welfare state in The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness (1944). Niebuhr's central claim was that the ideologies of the left (communism) and right (laissez-faire capitalism) both rested on a flawed conception of human nature. Human beings were driven by selfish desires, including a desire to exert power over others. But they were not rational utility maximizers. Rather, blinded by pride, they often pursued their aims in fundamentally irrational ways that defied the expectations of communist theorists and libertarian economists alike. In the long run, only governments that took the selfish and irrational aspects of human nature (what Niebuhr called “original sin”) into account were likely to endure. In practice, this meant that democratic nations should minimize human suffering via the creation of robust welfare states while simultaneously placing constitutional limits on the powers of officials who might otherwise ensconce themselves as an unaccountable ruling class (as Niebuhr believed had occurred in the Soviet Union).Footnote 54

Niebuhr's “neo-orthodox” defense of the liberal democratic welfare state, which was equally attractive to labor leaders and moderate Republican executives, provided the theological foundation for nearly all the DCEL's major pronouncements on economic affairs. Most obviously, it underpinned the group's effort to draft a formal statement of economic principles, which began in earnest in October 1952. At that month's meeting, the group debated a draft statement, mostly written by Niebuhr's friend and colleague John C. Bennett, entitled “Basic Principles and Assumptions of Economic Life.”Footnote 55 The document implored the nation's Protestants to advocate for “a minimum standard of living … sufficient for the health of all and for the protection of the weaker members of society … against disadvantages beyond their control”; for reasonable “standards of living, hours of labor, stability of employment, [and] provision of housing”; for a reduction of “inequalities in the distribution of wealth and income”; and for programs to combat “racial discrimination” in employment. It also praised the labor movement as “an instrument for the securing of greater economic justice and … a source of dignity … for workers.” These positions were justified not only because they were consistent with Protestant social teachings but also because they were well calculated to preserve democratic institutions and social stability. Indeed, the major lesson of the Depression and World War II years was that “there can be no Christian sanction for one-sided support of either economic individualism or economic collectivism.” Rather, “Christians should … seek the economic institutions which will in a given set of circumstances serve most fully … the positive values of justice and order and freedom.”Footnote 56

The “Basic Principles” statement became an immediate flashpoint in the battle to control the economic message of the nation's largest ecumenical group. In February 1953, shortly after Eisenhower's swearing-in, the DCEL formally approved it with the recommendation that it be adopted as a formal pronouncement of the NCC. Hopes of quick action by the NCC's general board were thwarted, however, when J. Howard Pew implicitly threatened to withdraw his financial support for the organization.Footnote 57 In response, the NCC's general secretary, Samuel McCrea Cavert, asked Hall and Taft to sand down passages that explicitly endorsed the welfare state.Footnote 58 But while the DCEL's leaders agreed to consider revisions, they refused to back down entirely. Instead, they formed a committee to revise the document, which was led by Wesley Rennie, the executive director of the Committee for Economic Development (CED) and a part-time economic advisor to the president.Footnote 59 In the end, Rennie and the other committee members agreed to incorporate new language on the communist threat and capitalism's role in raising living standards. However, they also retained most of the passages that had offended Pew and even added new language denouncing the view “held by some sincere Christians that a maximum of individual economic freedom will by itself create the economic conditions that contribute to a good society.”Footnote 60

The debate over the proposed statement came to a head in the spring and summer of 1954, just as congressional Republicans were locked in a bitter feud over the future of Social Security. In his 1954 State of the Union Address, Eisenhower had disappointed conservatives by confirming his support for a significant expansion of the program.Footnote 61 Legislation to this effect was soon working its way through Republican-controlled committees, but conservative lawmakers, backed by NAM and the U.S. Chamber, were simultaneously pushing legislation designed to undercut the program's funding mechanism.Footnote 62 For the handful of NCC officials who held posts in the Eisenhower administration—a group that included Flemming (director of Defense Mobilization), Harold Stassen (director of the Foreign Operations Administration), W. Howard Chase (assistant secretary of Commerce), and W. Walter Williams (undersecretary of Commerce)—the stakes of the “Basic Principles” debate could not have been clearer. Failure to secure a strong pro-welfare-state statement would almost certainly embolden the GOP's conservative wing. Conversely, a statement declaring support for Social Security and other domestic social welfare programs seemed likely to reinforce Ike's moderate tendencies while also sanctifying his centrist economic agenda as consistent with the social teachings of the nation's largest Protestant denominations. Hence, in April 1954, the DCEL voted to again forward the “Basic Principles” to the NCC's general board and to send notice that there would be no further revisions.Footnote 63 Although it was initially unclear whether NCC executives would risk further alienating the Pew forces by scheduling a vote, the retirement that spring of Cavert, the NCC's general secretary, created an opening.Footnote 64 By June, Flemming had successfully placed the statement on the agenda for the general board's September 1954 meeting—a move that all but ensured its adoption.Footnote 65

Final approval of the “Basic Principles” statement came in mid-September 1954, a few days after Eisenhower signed that year's major expansion of Social Security into law.Footnote 66 Because the statement had been in wide circulation since late spring, however, the near-certainty of its adoption by the NCC's left-leaning general board may have given administration moderates ammunition in the closing weeks of the Social Security debate.Footnote 67 Perhaps more importantly, the statement's adoption generated a flood of press coverage, nearly all of which cast a beatific glow over Eisenhower's domestic agenda. The New York Times and Washington Post featured front-page accounts, and the Times reprinted the 4,000-word document in its entirety.Footnote 68 These stories lauded the NCC—and, by implication, the president—for charting “a sensible middle course between economic anarchy … and collectivism” and for promoting “a responsible free enterprise system” as the Christian alternative to the totalizing ideologies of left and right.Footnote 69 In policy terms, the major takeaway was that the NCC had endorsed the principle of “a minimum standard of living” for “the weaker members of society” as well as the right of “the able-bodied” to protection “against hazards beyond their control.”Footnote 70 Coming so soon after the president had signed legislation extending Social Security benefits to ten million new workers—and raising benefits for millions already covered—such language could only have been interpreted as bestowing the churches’ blessing on what the Times called “the most significant achievement of the Administration in the 1954 session of Congress.”Footnote 71

Securing the adoption of the “Basic Principles” statement was arguably the DCEL's greatest achievement during the early years of the Eisenhower administration. But the group also advanced the neo-orthodox case for protecting the welfare state in other venues, including a series of popular books. Funded by a $225,000 grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, the Church and Economic Life book series consisted of several titles authored or coauthored by prominent academics and journalists.Footnote 72 The first volume, entitled Goals of Economic Life, arrived in bookstores in March 1953, shortly after Eisenhower's swearing-in. Featuring contributions from a long list of prominent academics—including Niebuhr, Bennett, and economists such as Frank Knight, Kenneth Boulding, and John Maurice Clark—each chapter addressed a specific empirical or ethical question concerning the contemporary economy. The authors were free to develop their own arguments, but drafts were submitted to the DCEL's members, who offered suggestions for revision.Footnote 73 Summarizing the book's major theme, Niebuhr's concluding chapter declared that “the healthiest democracies of the Western world have preserved or regained their social and economic health by using political power to redress the most obvious disbalances in economic society, to protect social values to which the market is indifferent, and to prevent or to mitigate the periodic crises to which a free economy seems subject.”Footnote 74

Goals of Economic Life received wide press coverage; it was the subject of a Times article and a national NBC Radio Roundtable discussion, for example.Footnote 75 Yet the book's influence paled in comparison to that of a subsequent volume in the series. Authored by the journalists Marquis Childs and Douglass Cater, Ethics in a Business Society appeared in March 1954, just as the congressional debate over Social Security expansion was nearing its climax. Deviating from their assigned task, which was to synthesize the previous volumes in the series, Childs and Cater penned a hard-hitting critique of the GOP right's economic philosophy. They attacked several of Eisenhower's advisors by name, alleging that Treasury Secretary George M. Humphrey, Commerce Secretary Sinclair Weeks, and other administration conservatives had failed to grasp the fundamental policy lesson of the past two decades, which was that only a “mixed economy in which the tradition of freedom and the tradition of social responsibility are kept in healthy balance” could deliver lasting prosperity.Footnote 76 Following an initial print run of 100,000 copies, Ethics in Business Society went through five additional printings between 1954 and 1962.Footnote 77 Like other books in the Church and Economic Life series, it was widely and positively covered in the press. In some cases, favorable coverage was engineered by the DCEL itself, as when one of its members, Illinois Senator Paul Douglas, secured the job of reviewing the book for the New York Times.Footnote 78

A final vehicle through which the DCEL articulated its Niebuhrian defense of the welfare state was the annual Labor Sunday message. The Labor Sunday tradition dated to the early twentieth century, when representatives of the Federal Council of Churches (FCC) had designated the Sunday before Labor Day as a day for addressing the concerns of working-class people (who, it was feared, were beginning to abandon organized religion).Footnote 79 The task of authoring and distributing the Labor Sunday message fell to the DCEL at the time of the NCC's launch in 1951. Every summer a subcommittee would draft—or recruit a well-known religious figure to draft—a brief message offering a condensed version of the group's recent pronouncements, complete with supporting biblical references. After review by the DCEL's members, the message was distributed in pamphlet form to Protestant congregations throughout the country, who were encouraged to incorporate it into Sunday services. It was also broadcast over the radio in most media markets and frequently reprinted in major newspapers.Footnote 80

During Eisenhower's first term, Labor Sunday messages typically stressed two themes. First, social welfare programs were not steppingstones on the path to communism but genuine embodiments of longstanding Protestant social teachings. Second, the welfare state offered the surest defense against anarchy and disorder, which were the true handmaidens of totalitarianism. The 1953 message—penned when there was still some uncertainty about Ike's position on Social Security—declared that “Social security is no luxury in a highly industrialized society. It is both Christian and practical to assist the sick, the crippled, the aged, and the young. Neglect of large groups of people who cannot help themselves invites the breakdown of society and violates a principle from which [our nation] draws its substance.”Footnote 81 The following year's message, released the same month as the “Basic Principles” statement and Eisenhower's signing of the 1954 Social Security expansion, merged Niebuhr's theological perspective with language drawn from FDR's “four freedoms” address, declaring that “freedom from want, whether want is caused by sickness, old age, or unemployment, is important both for the well-being of its members and the stability of society,” and that “wide contrast in the security of different groups” of Americans was incompatible with the development of “Christian humanistic relationships.”Footnote 82 In not so many words: It was the opponents of the New Deal order, not its supporters, who were flirting with godless social theories and threatening to disrupt an era of relative peace and prosperity.

Did the DCEL's publications and pronouncements exert a measurable influence on politicians, policymakers, or the wider public? The group's materials were sometimes cited on the campaign trail. In 1956, for example, numerous pro-labor candidates used DCEL study materials to attack proposed “right-to-work” laws, which were a pivotal issue in several of that fall's races.Footnote 83 Explicit references were less common in 1954 and 1955, but the extent to which Ike's speechwriters—some of whom had connections to the NCC—drew on the arguments of NCC tracts is nonetheless noteworthy.Footnote 84 In his 1955 State of the Union Address, for example, Eisenhower listed Social Security expansion first in a list of domestic accomplishments, noting that while he would prefer to allow citizens to fulfill their “aspirations … without government interference,” state intervention in the economy was sometimes necessary to provide citizens with “recognition and respect” and to help them “give full expression to [their] God-given talents and abilities.” Four months earlier, the NCC had warned of the dangers of a “thoroughgoing collectivism” while also stressing that “some use of government in relation to economic activities” was necessary to protect the “dignity and possibilities of all persons” and to “provide the environment in which human freedom can flourish.” In the same speech, Eisenhower stressed that his economic program aimed to raise Americans’ “material standard of living,” not so they could “accumulate possessions” but to create “an environment in which families may live meaningful and happy lives.” Or as the NCC had earlier put it, nations blessed with “a rising standard of living” should not direct their energies toward “the acquisition and enjoyment of material things” but should instead ensure that economic policies “serve[ed] human need” and exerted a positive “impact on the family.”Footnote 85

Over the course of 1953 and 1954, Eisenhower apparently came to view the NCC's leaders as ideological allies whose implicit support for his domestic agenda promised to insulate his administration from critics on both the left (labor leaders) and right (conservative Republicans). He may also have been grateful for the NCC's public campaign against Joseph McCarthy and red-baiting congressional investigators, an effort that culminated in late 1953 and early 1954 just as investigators were turning their fire on the administration.Footnote 86 Whatever the reason, Eisenhower began to cultivate a close relationship with the NCC at the precise moment when Arthur Flemming, Harold Stassen, and other administration moderates were working through the organization to build support for their preferred policies. In addition to holding regular meetings with NCC executives at the White House—presumably at the behest of Flemming and Stassen—the president began to circulate NCC position papers to his staff. Footnote 87 He also increasingly sought out opportunities to appear with NCC officials in public. In August 1953, he addressed a convention of the United Church Women, an NCC subsidiary, in Atlantic City.Footnote 88 Three months later, accompanied by several cabinet members, he spoke to a luncheon meeting of the NCC's general board.Footnote 89 Then, in August 1954, he joined numerous NCC officials at the second assembly of the World Council of Churches (WCC) in Evanston, Illinois.Footnote 90 Finally, in May 1955 a delegation from the United Church Men—another NCC subsidiary—traveled to the White House, where they presented the president with a special “Layman of the Year” citation.Footnote 91

Congressional conservatives, predictably, were less than pleased by Ike's sudden affinity for religious organizations with left-of-center reputations. Some went so far as to complain that the president had turned his domestic agenda over to the NCC and other “social equality groups.”Footnote 92 Politically conservative religious leaders were equally unhappy. Carl McIntire, the radio preacher and NCC critic who headed the fundamentalist American Council of Churches, lamented that Ike had joined forces with liberal ecumenical groups like the NCC and WCC “to the harm and discredit” of conservative believers everywhere.Footnote 93

5. The DCEL and the Protestant Grassroots

Each of the DCEL's three major initiatives during the 1953–54 period served to reframe the policy achievements of the New Deal and Fair Deal years not as victories in an ongoing class struggle but as essential components of an ethical society. This argument gained added force whenever its parent organization, the NCC, partnered with Jewish and Catholic organizations to issue policy-oriented pronouncements, as it sometimes did.Footnote 94 But religious groups were not alone in making the case against the libertarian economic vision of the GOP's resurgent right wing. Indeed, as right-wing critics of the NCC frequently pointed out, the organization was but a single node in a larger, mostly secular network of center-left organizations—including the Committee for Economic Development (CED), Americans for Democratic Action (ADA), and the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations—whose leaders’ shared economic ideals included support for the welfare state, powerful but “responsible” labor unions, Keynesian approaches to monetary and fiscal policy, firm opposition to communism, and robust foreign aid programs.Footnote 95 The overlap in membership between the DCEL and its secular allies was extensive. DCEL members in the early 1950s included the president (W. Walter Williams), past president (Paul G. Hoffman), and executive director (Wesley Rennie) of the CED; the presidents of the Ford (Hoffman) and Rockefeller (Chester I. Barnard) Foundations; numerous board members of these organizations, including Charles Taft and J. Irwin Miller; and several founding members of the ADA, including Reinhold Niebuhr, Marquis Childs, and Walter Reuther.Footnote 96

To point out the DCEL's position within this constellation of groups is to raise a pair of larger questions: What, if anything, distinguished the DCEL from the other postwar organizations that were simultaneously working to prevent the dismantling of the New Deal's legacy? And why did White House advisors like Stassen and Flemming—to say nothing of the president—choose to devote time and energy to a modestly funded religious group when other, seemingly more powerful organizational vehicles for promoting administration priorities were readily available?

The short answer is that the DCEL, owing to its status as a subordinate unit of the NCC, possessed several advantageous characteristics that its better-known counterparts lacked. First, and most obviously, it was the only center-left economic advocacy group whose pronouncements were grounded in holy writ. Where groups like the CED and Ford Foundation gained credibility from the academic qualifications of the social scientists who authored their policy reports, the DCEL—while often employing the very same academics—buttressed its recommendations with copious citations to the Bible and the social teachings of the Protestant denominations.Footnote 97 This framing—which, as we have seen, appealed to White House speechwriters—was especially crucial at a moment when NAM and other conservative groups were spending lavishly on church-based “educational” campaigns that traced a direct line from the Gospels to the insights of the Austrian School economists.Footnote 98

A second factor that added gravitas to the DCEL's policy pronouncements was the diversity of the group's membership. The presence of names like Walter Reuther, Boris Shishkin, and Nelson Cruikshank on its letterhead meant that neither policymakers nor the public could dismiss the DCEL's policy recommendations as providing religious cover for big business. Of the DCEL's organizational allies, only the ADA claimed a similarly impressive slate of labor leaders. However, the ADA's influence on policymakers and public opinion was limited by its close links to the Democratic Party and by an unwieldy decision-making process that often resulted in erratic position changes.Footnote 99 The DCEL, in contrast, was both thoroughly bipartisan—nearly all its business representatives were moderate Republicans—and small enough to permit decision-making procedures that were both efficient and genuinely deliberative.

A third characteristic that likely made the DCEL attractive as a vehicle for center-left policy advocacy was the group's relative immunity from the red-baiting attacks that dogged many of its organizational allies. At a time when the ADA, the Ford Foundation, and other liberal groups were caught in the crosshairs of congressional investigators, the NCC and its subordinate units remained mostly above the fray—in part because the NCC's founders had designed it to withstand such attacks.Footnote 100 To be sure, hardline anticommunist religious leaders like Carl McIntire alleged that the NCC bureaucracy was riddled with communists and fellow travelers.Footnote 101 But such attacks, which had devastated the now-defunct FCC, were relatively easy to deflect when aimed at an organization whose general board included the heads of General Electric, Armco Steel, and other major corporations, and whose newly created Lay Committee included some of the nation's most fanatical anticommunists, including McIntire's friend and patron J. Howard Pew.Footnote 102

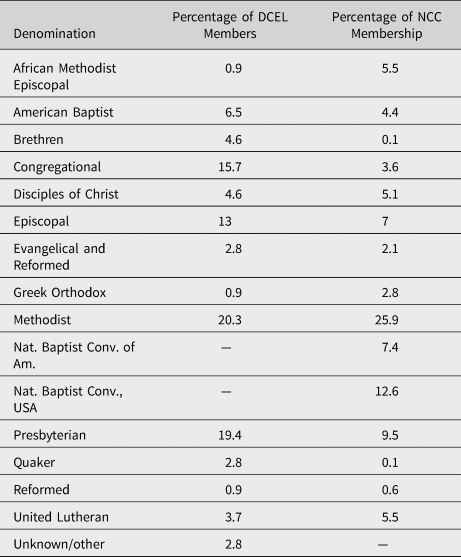

And yet the DCEL's single greatest attribute, from the perspective of those hoping to preserve the core of New Deal, was its connection to the larger universe of mainline Protestant churchgoers. In one sense, the group's claim to be the “voice” of American Protestantism on economic matters was unpersuasive, since leaders made little effort to discern the views of rank-and-file churchgoers before issuing policy pronouncements. But the carefully scripted democratic procedures through which the NCC and its subordinate units were constituted meant that these entities were in some sense representative of Protestantism writ large. For example, the bylaws of the NCC and DCEL stipulated that their governing bodies were to be staffed primarily by lay people and that seats on these bodies were to be apportioned in accordance with the relative size of the NCC's member denominations (see Table 2).Footnote 103 In addition, the NCC—though not the DCEL—required that representatives to its general board be selected by the denominations themselves, usually through some sort of democratic conclave such as a national convention. Taken together, these procedures allowed the NCC to credibly “speak for” white Protestant churchgoers in the same sense that, say, the AFL-CIO “spoke for” for an unwieldy group of labor unions whose views were not easily harmonized.Footnote 104

Table 2. Denominational Representation in the DCEL

Source: Department of the Church and Economic Life, “Study of Attendance at Eight Meetings,” National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America Records, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, PA, RG4, box 1, folder 21; Benson Y. Landis, ed., Yearbook of American Churches (New York: National Council of Churches of Christ in the U.S.A., 1953).

It would be a mistake, however, to dismiss either the DCEL or NCC as organizations that merely created the appearance of connections to the grassroots. In fact, as we have seen, the NCC sat atop a well-funded and rapidly expanding system of state and local Protestant church councils. Under the leadership of education committee chair (and part-time White House advisor) Wesley Rennie, and with funding provided by the Methodist Council on World Service and a grant from the Philip Murray Memorial Foundation (in effect, the CIO), the DCEL used the church council network to take its message directly to average churchgoers.Footnote 105 The councils provided a speaking circuit for DCEL members including Cameron Hall, Charles Taft, and Marquis Childs, who regularly traveled to address events organized by local councils.Footnote 106 State and local councils also assisted with disseminating DCEL-sponsored books, “study materials,” filmstrips, and other educational publications.Footnote 107 Finally, because broadcast regulations granted them control over significant blocs of free airtime, local councils provided the DCEL with unmatched access to radio and television audiences, which it used to air roundtable discussions focused on its own study materials and pronouncements.Footnote 108

The DCEL's annual “Church and Economic Life Week” provides a vivid illustration of the church councils’ importance as venues for reaching average churchgoers. In 1948, two years before the founding of the NCC, the FCC asked local congregations to set aside a week in late January for events dedicated to investigating “Christian” solutions to current economic problems. The tradition continued under the NCC, with the reconstituted DCEL taking responsibility for program materials, and state and local church councils planning events in local communities. The highlight of a local Economic Life Week was typically an evening or weekend program featuring addresses from prominent labor and business leaders, followed by small group discussions organized around study materials provided by the DCEL.Footnote 109 In addition, in even-numbered years, attendees elected a slate of delegates to attend a national Church and Economic Life conference.Footnote 110 The national conference was similar to the local meetings, except that attendees were expected to approve a conference report that offered policymakers guidance on current economic challenges. The sheer size of the national gatherings—which often featured 400 or more delegates, including representatives of labor, business, government, academia, agriculture, and the clergy—ensured wide press coverage.Footnote 111 More to the point, the DCEL's control of the agenda reliably produced conference reports that reflected its own center-left vision. Prime speaking slots were reserved for DCEL members, including Walter Reuther and Charles Taft, and a draft conference report was usually prepared in advance (although conservative delegates sometimes succeeded in watering down its provisions.)Footnote 112 The final product typically declared “the Protestant laity's” support for a strong welfare state, basic labor-organizing protections, generous foreign aid programs, and federal action on civil rights.Footnote 113

Hence, while the DCEL was far from the only civil society group that defended the welfare state against the GOP conservative wing's attacks, it was arguably the only such group that could claim broad representation from across the partisan and economic spectrum and viable connections to the Protestant grassroots. Its pronouncements almost certainly carried greater weight with policymakers and the public than those issued by groups that were clearly aligned with the Democratic Party (e.g., organized labor, the ADA) or that lacked meaningful connections to rank-and-file voters (e.g., the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations and the CED). Moreover, as we shall see in the next section, the DCEL's successful effort to establish itself as the unofficial voice of American Protestantism on economic affairs had the added—but largely unanticipated—benefit of exacerbating latent fissures in the Protestant right.

6. The Fracturing of the Protestant Right

In 1951, as we have seen, J. Howard Pew and a group of conservative allies launched the National Lay Committee for the purpose of blunting the DCEL's influence within the NCC. But this effort ultimately failed. In September 1954, when the NCC's general board adopted a statement of economic principles that clashed with Pew's libertarian convictions, the retired oil executive dissolved the Lay Committee and severed all ties with the NCC.Footnote 114

With the benefit of hindsight, a more effective strategy for Pew and other conservative Protestants would have been to attack the NCC from the outside rather than attempting to co-opt it from within. But in 1951 there were reasons to believe that a conservative takeover of the council might succeed. Recognizing that the NCC's organizers were deeply concerned about the group's finances, Pew filled his Lay Committee with conservative businessmen who promised to back the NCC financially.Footnote 115 His goal, as he acknowledged in correspondence with various Lay Committee members, was to make the NCC financially dependent on the Lay Committee. If this could be achieved, he reasoned, then the NCC would have little choice but to ensure that its policy pronouncements met with the approval of the Lay Committee's overwhelmingly conservative membership.Footnote 116

So why did the plan fail? First, the Pew forces made the critical mistake of aligning themselves with the NCC—and thus boosting the new organization's credibility—without first securing a place for themselves within the organization's formal governing structures. Apparently believing that financial contributions alone would grant them effective control over the NCC's ideological direction, they established the Lay Committee as a purely advisory body. But the “stick” of reduced financial contributions proved too blunt an instrument for Pew's aims. Within a year or two of the NCC's founding, a surge in church attendance and giving had allowed the mainline denominations to fill its coffers. And with funding pouring in from a variety of secular sources, including the Rockefeller Foundation and the CIO, the NCC leaders’ early concerns about their organization's financial viability faded.Footnote 117 Although NCC officials were willing to placate the Pew forces up to a point, financial considerations did not prevent them from siding with the moderates in the DCEL when the escalating conflict between the two groups forced their hand. (Nor did it hurt that many DCEL members were themselves generous donors to the NCC.) Their bluff called, the conservatives discovered that, as one of Pew's correspondents put it, they lacked an intra-organizational foothold from which to veto the economic pronouncements of “left-wing church officialdom.”Footnote 118

To be sure, Pew did manage to secure the appointment of a handful of allies to the NCC's general board. He also managed to have some close associates named as vice presidents of the NCC, including Ruth Stafford Peale (wife of the minister and popular self-help author Norman Vincent Peale), Olive Ann Beech (president of Beech Aircraft), and Jasper Crane (retired DuPont executive and prominent funder of conservative organizations). But these appointments were, in the end, counterproductive. Control of a half-dozen seats on the 250-person general board was hardly sufficient to influence the outcome of important votes.Footnote 119 Meanwhile, the presence of prominent conservative names such as Peale, Beech, and Crane on the NCC's letterhead helped seal the council's reputation as a middle-of-the-road organization in which both conservatives and liberals were amply represented.

What transpired between summer 1952 and late 1954, then, was that the Pew forces inadvertently lent credence to the NCC's initially tendentious claim to be the “voice” of American Protestantism on economic affairs. Because its lay leadership was both bipartisan and ideologically diverse—including both well-known liberals and pillars of the far right—the NCC soon became a popular venue for politicians who hoped to position themselves above the partisan fray. And every time a political leader heaped praise on the NCC, the organization's claims to leadership of “Protestant America” grew more plausible.

As we have seen, Ike himself attended the NCC's general board meeting in the fall of 1953, where he lauded the council for advancing “the principle of the equality of man, the dignity of man.”Footnote 120 The president's remarks were particularly noteworthy, as they came shortly after the NCC's president, the Episcopal Bishop Henry Knox Sherrill, in an obvious rebuke to the Pew forces, had urged the same audience not to shrink from “apply[ing] the Gospel” to even the most controversial fields, including “the international and the economic.”Footnote 121 Eisenhower would continue to shower praise on the NCC over the course of his presidency, even going so far as to lay the ceremonial cornerstone of the organization's New York City headquarters.Footnote 122 Moreover, several of his top advisors—including Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, UN Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., and Director of Foreign Operations Harold Stassen—headlined NCC events where they, too, waxed eloquent about the organization's contributions to the religious life of the nation and the moral improvement of humanity.Footnote 123

By the fall of 1954, when Pew finally cut ties with the NCC, efforts to paint the council as a tool of organized labor—let alone as a hotbed of communist influence—stood little chance of success. And indeed, Pew's attempts to turn public opinion against the council by airing his grievances in the press backfired badly. With few exceptions, stories on the pivotal September 1954 general board meeting stressed the lopsided nature of the vote in support of the “Basic Principles” statement, noting that the document won “overwhelming approval” despite protests from a “small” and “highly vocal” minority whose ultimate aim was to veto all pronouncements “in the field of social, political, and economic activity.”Footnote 124 Pew's subsequent decision to disband the Lay Committee and publish a trove of documents purporting to document his unfair treatment by the NCC's leadership yielded equally poor results. Far from vindicating Pew and his allies, the documents seemed to confirm, in the words of one critic, that the Pew forces had aimed to become a “House of Lords, with veto power of those actions of the officially appointed representatives of the churches which did not suit them.”Footnote 125