INTRODUCTION

Lexical tones, while essential for conveying semantic meaning in tonal languages, pose a multitude of problems for speakers of nontonal languages and are difficult to acquire (Hao, Reference Hao2012; Wayland & Guion, Reference Wayland and Guion2004). Difficulties arise from nontonal language speakers’ reliance on other acoustic properties when attending to tones and other phonetic features (Wang, Reference Wang2013; Zhang, Nissen, & Francis, Reference Zhang, Nissen and Francis2008), the unfamiliar integration of syllable with tone (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang, Perfetti, Brubaker, Wu and MacWhinney2011), as well as a general lack of attention to pitch changes compared to native speakers (NS) of tone languages (Guion & Pederson, Reference Guion, Pederson, Bohn and Munro2007). Despite this, there is little research to date that investigates how tones are best learned and taught and very few investigations in classroom contexts. Second language acquisition (SLA) research adopting an interactionist perspective (Gass, Reference Gass1997; Gass & Mackey, Reference Gass and Mackey2006; Long, Reference Long, Ritchie and Bhatia1996, Reference Long2007; Mackey Reference Mackey1999) has sought to affirm the link between interaction and second language (L2) development positing that exposure to input, output, negotiation for meaning, and corrective feedback are the critical ingredients in successful SLA. Based on decades of empirical investigations (see Mackey & Goo, Reference Mackey, Goo and Mackey2007; Russell & Spada, Reference Russell, Spada, Ortega and Norris2006; Ziegler, Reference Ziegler2016 for meta-analyses), there is robust evidence connecting interaction to L2 development for a variety of grammatical and discourse features. This line of research has in particular extensively investigated the effects of oral corrective feedback on various aspects of SLA (Li, Reference Li2010; Lyster & Saito, Reference Lyster and Saito2010; Mackey & Goo, Reference Mackey, Goo and Mackey2007) with studies examining types of feedback, the linguistic target of feedback and its varied effectiveness in a wide range of contexts (e.g., Ammar & Spada, Reference Ammar and Spada2006; Goo, Reference Goo2012; Leeman, Reference Leeman2003; Mackey & Philp, Reference Mackey and Philp1998; Sheen, Reference Sheen2008). Particular attention has been paid to recasts, reformulations of a learners’ error by a more proficient or NS (e.g., Ammar & Spada, Reference Ammar and Spada2006; Carpenter, Jeon, MacGregor, & Mackey, Reference Carpenter, Jeon, MacGregor and Mackey2006; Lyster & Ranta, Reference Lyster and Ranta1997; Mackey & Philp, Reference Mackey and Philp1998; Mackey et al., Reference Mackey, Gass and McDonough2000). In the following example (1) from the current study, which occurred during a role-play scenario in which a student could not remember a critical vocabulary word, the instructor recasts a phonological error in a student’s production of Mandarin Chinese tone (numerals indicate the four Mandarin tones, high, high-rising, low-dipping, and high-falling, respectively, and Mandarin characters are represented in pinyin, the standard Romanization of Mandarin Chinese).

While more implicit feedback (such as the recast in the preceding example) has received considerable attention in previous corrective feedback research, the degree to which more implicit or more explicit feedback, such as metalinguistic explanations, is more effective has been continuously debated (Goo & Mackey, Reference Goo and Mackey2013; Lyster & Saito, Reference Lyster and Saito2010; Lyster, Saito, & Sato, Reference Lyster, Saito and Sato2013) along with the role contextual features and characteristics of the feedback play in how explicitly the feedback is interpreted (e.g., Sheen, Reference Sheen2004).

Despite a call for further research into the effects of interaction and corrective feedback on L2 phonology (e.g., Mackey, Abbuhl, & Gass, Reference Mackey, Abbuhl, Gass, Gass and Mackey2012; Parlak & Ziegler, Reference Parlak and Ziegler2017; Solon, Long, & Gurzynski-Weiss, 2014), most previous research has focused on the acquisition of lexical and grammatical forms. In the domain of phonology, preliminary findings indicate that implicit corrective feedback on phonological errors is particularly salient to learners (Mackey et al., Reference Mackey, Gass and McDonough2000; Saito, Reference Saito2015; Saito & Lyster, Reference Saito and Lyster2012) and therefore potentially more effective for tone learning. However, explicit corrective feedback has been shown to be more effective for beginners (Li, Reference Li2009, Reference Li2014), at least for morphosyntactic features such as Chinese classifiers, and is more easily noticed by learners (e.g., Nassaji, Reference Nassaji2009). Furthermore, there is growing interest in computer-mediated communication (CMC) environments and the role they play in facilitating interaction (see Ziegler, Reference Ziegler2016 for a meta-analysis), corrective feedback (Parlak & Ziegler, Reference Parlak and Ziegler2017), and L2 pronunciation training (Loewen & Isbell, Reference Loewen and Isbell2017); however, many of these studies occur in experimental or controlled settings rather than in preexisting online courses. The current study aims to untangle these disparate findings by investigating the effects of more explicit versus more implicit corrective feedback on beginner learners’ perception and production of Mandarin tones in a classroom SCMC context.

LITERATURE REVIEW

INTERACTION, CORRECTIVE FEEDBACK, AND L2 PHONOLOGY

In the interactionist approach to SLA (Gass, Reference Gass1997; Gass & Mackey, Reference Gass and Mackey2006; Long, Reference Long, Ritchie and Bhatia1996), interaction between second language learners and more proficient speakers is viewed as the critical component of successful language acquisition. One of the most investigated features of the interaction approach to SLA is the provision of corrective feedback. Feedback can range from simply an indication than an error has occurred and has caused a communication breakdown, such as a clarification request (e.g., “Sorry, I didn’t understand you”), to a metalinguistic explanation of how the error should be corrected (e.g., “In English you need to add an –s to make plural words”). In this regard, corrective feedback moves are frequently discussed and studied in terms of their relative explicit or implicitness and may be viewed as a continuum that is dependent on the context of the error and provision of feedback (Ellis, Reference Ellis2001).

Recasts are a prototypical form of implicit corrective feedback that have garnered much attention in interaction research (see Goo & Mackey, Reference Goo and Mackey2013; Mackey, Reference Mackey2012 for overviews) by simultaneously providing positive linguistic evidence to the learner and juxtaposing that positive evidence against the learners utterance without interrupting meaningful discourse. The degree to which learners perceive recasts as negative evidence has been previously debated (Goo & Mackey, Reference Goo and Mackey2013; Lyster & Saito, Reference Lyster and Saito2010), yet these issues have mainly been discussed in terms of L2 morphosyntax development (Saito, Reference Saito2013). In the domain of phonology, recasts have shown to be particularly salient to learners (Mackey et al., Reference Mackey, Gass and McDonough2000) and therefore potentially more effective. Saito and Lyster (Reference Saito and Lyster2012) have speculated that phonological recasts are more salient because learners cannot easily misinterpret them as reformulations of utterances, as is the case of morphosyntactic recasts that are sometimes ambiguous with clarifications. Carpenter et al. (Reference Carpenter, Jeon, MacGregor and Mackey2006), for instance, found that morphosyntactic recasts were less accurately recognized by advanced English-as-a-second language (ESL) learners than phonological or lexical recasts. Learners’ ability to “notice the gap” between their own production and that of native or proficient speakers (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt1990) has be connected to acquisition in a variety of studies (e.g., Leeman, Reference Leeman2003; Mackey, Philp, Fujii, Egi, & Tatsumi, Reference Mackey, Philp, Fujii, Egi, Tatsumi and Robinson2002; Philp, Reference Philp2003). The tendency for learners to more readily notice and correct phonological errors specifically has been demonstrated in studies across a variety of contexts including French immersion classrooms (Lyster, Reference Lyster1998), adult ESL, and English-as-a-foreign language (EFL) classrooms (Ellis, Basturkmen, & Loewen, Reference Ellis, Basturkmen and Loewen2001) as well as in the lab (Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Jeon, MacGregor and Mackey2006; Mackey et al., Reference Mackey, Gass and McDonough2000; Saito, Reference Saito2013; Saito & Lyster, Reference Saito and Lyster2012). In these studies, students who received recasts on phonological errors successfully repaired, or modified their output in the next turn, more often than they did after recasts of morphosyntactic errors. The modification of output following feedback has been shown to enable learners to compare their output to the interlocutor’s model, juxtaposing their error against the correction and fostering automaticity (Swain, Reference Swain and Hinkel2005). However, most of these previous studies have investigated specific segmental phoneme learning (according to a review by Gut, Reference Gut2009) such as the acquisition of the English /r/ by Japanese learners of English (Saito, Reference Saito2015; Saito & Lyster, Reference Saito and Lyster2012), the production of vowels (Flege, Bohn, & Jang, Reference Flege, Bohn and Jang1997; Lee & Lyster, Reference Lee and Lyster2016a, Reference Lee and Lyster2016b), and less on stress, prosody and intonation (Parlak & Ziegler, Reference Parlak and Ziegler2017; Piske, MacKay, & Flege, Reference Piske, MacKay and Flege2001; Trofimovich & Baker, Reference Trofimovich and Baker2006).

Whether more implicit or more explicit forms of phonological corrective feedback are the most effective, recasts are the feedback move most often used by teachers in face-to-face language classrooms for all linguistic targets (Brown, Reference Brown2016; Lyster & Ranta, Reference Lyster and Ranta1997; Sheen, Reference Sheen2004), possibly due to the fact that implicit feedback has been shown to promote the flow of meaning making in the classroom and is more naturalistic (Long, Reference Long, Ritchie and Bhatia1996, Reference Long2007). Despite this increasing interest in the effectiveness of phonological recasts, other factors, such as L2 proficiency level (Li, Reference Li2009) or developmental readiness (Mackey & Philp, Reference Mackey and Philp1998), have been shown to moderate the potential benefits of corrective feedback.

PROFICIENCY AS A MODERATOR OF CORRECTIVE FEEDBACK

Previous research has suggested that there is an interplay between the effects of corrective feedback and the L2 proficiency level of the learner (see Ziegler & Bryfonski, Reference Ziegler, Bryfonski, Malovrh and Benati2018 for an overview). Findings suggest that lower proficiency learners may stand to benefit less than higher proficiency learners from certain types of corrective feedback due to their limited attentional resources (Gass, Svetics, & Lemelin, Reference Gass, Svetics and Lemelin2003) and limited previous linguistic experiences (Philp, Reference Philp1999). Moreover, low proficiency learners have been shown to be more susceptible to crosslinguistic transfer from their L1 prosodic system than more advanced learners (Nguyễn, Ingram, & Pensalfini, Reference Nguyễn, Ingram and Pensalfini2008). A series of studies by Li (Reference Li2009, Reference Li2014) uncovered a complex relationship between learners’ proficiency level, the explicitness of the feedback provided, and the linguistic target of the feedback. In one study (Li, Reference Li2009), learners from two different levels enrolled in a L2 Chinese program received either implicit (recasts) or explicit (metalinguistic explanations) feedback on their production of Chinese classifiers during task-based interaction. Results indicated that lower proficiency learners benefited more from explicit feedback than implicit feedback. In a second study (Li, Reference Li2014), the effects of implicit versus explicit feedback were again examined this time with two different grammatical structures as the targets of the feedback. For one of the grammatical structures, the same results were found as in the previous study, recasts benefited the high proficiency but not the low proficiency learners. However, for the other structure, both high and low proficiency learners benefited from recasts indicating a potential relationship between target feature, proficiency level, and explicitness of corrective feedback. While these results prove interesting for morphosyntactic features, such as Chinese classifiers in this case, less is known about the effects of corrective feedback on phonological errors for varying levels of proficiency.

These results align with previous studies that suggested lower proficiency learners cannot as easily attune to implicit feedback due to their taxed attentional resources (Gass et al., Reference Gass, Svetics and Lemelin2003) and are therefore less able to accurately recall implicit corrective feedback after engaging in task-based interactions than higher proficiency learners (Philp, Reference Philp1999). Explicit feedback such as metalinguistic cues may provide lower proficiency learners the clearer signaling they need to recognize and correct the error they committed. Lower proficiency learners are generally less aware of corrective feedback and target forms (Atanassova, Reference Atanassova2012) whereas advanced learners’ noticing of corrective feedback is less influenced by type of feedback or target feature (as found in Li, Reference Li2014 reported previously). The timing of the delivery of corrective feedback is yet another factor that has been shown to interplay with proficiency level. A study by Li et al. (Reference Li, Ellis and Shu2016) examined the difference between immediate versus delayed feedback for learners at high and low proficiency levels. After EFL Chinese students performed two dictogloss tasks it was found that low proficiency learners benefited most from immediate feedback with high proficiency learners benefited equally from immediate and delayed feedback. These findings offer further support to the notion that lower proficiency learners do not have the same attentional resources available to process implicit or delayed feedback as their higher proficiency peers and may stand to gain more from explicit feedback.

Learners from various proficiency levels have also shown to vary in their preference for corrective feedback types (Lyster et al., Reference Lyster, Saito and Sato2013) and these preferences in turn have been linked to learning behaviors (Borg, Reference Borg2003). A study by Lee (Reference Lee2013) found through classroom observation, interviews, and questionnaires that although recasts were the most common type of feedback offered to advanced ESL learners, the learners preferred immediate explicit corrections even in the middle of an utterance. These preferences were at odds with the feedback preferences of the course instructor who did not feel it was appropriate to correct all errors. Teachers have been previously shown to prefer recasts for all proficiency levels as they are more efficient and are conducive to maintaining a “supportive classroom environment” (Yoshida, Reference Yoshida2008, p. 89). In a study by Brown (Reference Brown2009), advanced learners preferred more indirect/implicit feedback and preferred the opportunity to work out their own errors and self-repair, which is more likely to be effective as proficiency increases (Lyster et al., Reference Lyster, Saito and Sato2013). These findings highlight the potential for a mismatch between learners’ and instructors’ preferences and perceptions of corrective feedback, which may have consequences for language learning (Nunan, Reference Nunan and Johnson1989). While the literature reviewed in the preceding text demonstrates interesting interactions between proficiency level and the efficacy of corrective feedback, these studies have mainly examined grammatical and not phonological features as the targets of corrective feedback.

NONNATIVE LEXICAL TONE ACQUISITION

The target feature of the current study, lexical tone, is often perceived (by nontonal language speakers) to be one of the most difficult linguistic features to acquire. In tonal languages, lexical items are minimally distinguished by contrastive tones rather than phonemes. Therefore, success in second language learners’ ability to use and produce tonal contrasts to distinguish word meaning is critical for comprehension and production of the L2. Despite this, investigations of tone acquisition and tone-word learning are relatively recent (e.g., Cooper & Wang, Reference Cooper and Wang2012, Reference Cooper and Wang2013; Wong & Perrachione, Reference Wong and Perrachione2007) and underresearched. Previous studies have demonstrated the relative disadvantage nontonal language speakers have in the perception of lexical tone (Wayland & Guion, Reference Wayland and Guion2004) and pointed out that speakers of nontonal languages may not be able to perceive lexical tone despite recognizing the pitch changing (Flege, Reference Flege and Strange1995). According to Flege’s Speech Learning Model (1995), even when there is an audible difference between an L2 sound and the closest L1 sound, no new L2 speech sound category will be established if the learner cannot perceive the difference (Flege, Reference Flege and Strange1995). This is due to the significant impact the L1 sound system has on the learning of L2 sound segments (Flege, Schirru, & McKay, Reference Flege, Schirru and MacKay2003). In fact, there is some evidence claiming that nontonal language speakers simply do not attend to the direction of pitch change when compared with tonal language speakers (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang, Perfetti, Brubaker, Wu and MacWhinney2011). According to Wang (Reference Wang2013), learners from nontonal language backgrounds are disadvantaged because “tone and non-tone language speakers rely on different phonetic/acoustic cues in contrasting lexical tones” (p. 145). For example, while L1 Mandarin speakers primarily utilize the F0 (fundamental frequency, or the frequency of vocal fold vibration) contour to distinguish tones, L1 English speakers focus on absolute tone height (Wang, Jongman, & Serrano, Reference Wang, Jongman and Sereno2003).

Despite these disadvantages for nontonal language speakers, there is evidence that tone perception can be improved with experience (Wang, Spence, Jongman, & Serrano, Reference Wang, Spence, Jongman and Sereno1999). For example, Wayland and Li (Reference Wayland and Li2007) found that native English speakers could be trained to discriminate Thai tone contrasts through forced-choice identification, or categorical same/different discrimination procedures. Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Wang, Perfetti, Brubaker, Wu and MacWhinney2011) were able to train U.S. college students to better perceive Mandarin tones by showing them visual pitch contours depicting the acoustic shape of the tones. Furthermore, Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Spence, Jongman and Sereno1999) improved identification of Mandarin tones in English learners of Mandarin after extensive auditory training. Previous research in cross-language speech perception has also associated nonnative perception of phonology with L2 production errors (Flege, Reference Flege and Strange1995). Researchers such as Wayland and Guion (Reference Wayland and Guion2004) have argued that an increase in perception using training procedures is related to an improvement in tone production and even leads to corresponding neurophysiological changes. Additionally, increased outside exposure to language production has been linked to improved accent ratings and segmental accuracy in some studies (Trofimovich & Baker, Reference Trofimovich and Baker2006). However, success from training in laboratory settings has been shown to vary widely between individuals (e.g., Gottfried, Staby, & Ziemer, Reference Gottfried, Staby and Ziemer2004; Wong & Perrachione, Reference Wong and Perrachione2007); for example, learners with high aptitude for identifying pitch patterns in nonlexical contexts outperformed learners with less aptitude in terms of tone learning success for native English speakers with no prior experience with tone languages (Wong & Perrachione, Reference Wong and Perrachione2007). Additionally, individual musical ability has been associated with an increased accuracy in identifying and discriminating lexical tone (Gottfried et al., Reference Gottfried, Staby and Ziemer2004; Li & DeKeyser, Reference Li and DeKeyser2017; Wong, Skoe, Russo, Dees, & Kraus, Reference Wong, Skoe, Russo, Dees and Kraus2007) suggesting an initial advantage for learners with extensive musical backgrounds (Cooper & Wang, Reference Cooper and Wang2012). However, the majority of research investigating nonnative lexical tone acquisition has utilized training procedures in laboratory settings (e.g., Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang, Perfetti, Brubaker, Wu and MacWhinney2011) rather than investigating tone learning in authentic classroom contexts.

MANDARIN TONES

The target feature of the current study, Mandarin Chinese lexical tone, conveys critical information for language comprehension. In Mandarin, the four lexical tones differentiate word meanings. Tone 1 has a high-level pitch (“ -”), Tone 2 has a high-rising pitch (“ ´ ”), Tone 3 has a low-dipping pitch (“ ˇ ” ), and Tone 4 has a high-falling pitch (“ ` ”). The syllable pa, for example, can have four different meanings when distinguished by one of the four tones: eight (/pā Footnote 1 / high level), to pull (/pá 2 / high rising), handle (/pă 3/ low-dipping), and father (/pà 4 / high falling) (superscript numbers denote tone). This is in contrast to intonation languages, or “stress-accent languages” (Beckman, Reference Beckman1986) such as English that do not use pitch variation to discriminate word meaning. Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Wang, Perfetti, Brubaker, Wu and MacWhinney2011) cites the temporal integration of syllable and tone as one obstacle for Mandarin language learners because the learner has to simultaneously process both the segments and tone.

While many previous studies have aimed to improve English speakers’ Mandarin tone perception using training procedures in the laboratory (Cooper & Wang, Reference Cooper and Wang2013, Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang, Perfetti, Brubaker, Wu and MacWhinney2011; Wayland & Li, Reference Wayland and Li2007), few have examined tone learning by applying methods traditionally used by language teachers. Furthermore, most studies have used discrimination tasks (Li, Reference Li2016) or other techniques such as pitch-contour images (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang, Perfetti, Brubaker, Wu and MacWhinney2011) to investigate tone acquisition and learning rather than pedagogical, reactive practices, such as corrective feedback, already present and accessible to teachers in Mandarin language classrooms.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Despite the difficulty of acquisition of Mandarin tone for L1 English speakers, there is a dearth of knowledge on how tones are best learned and taught. The current, quasi-experimental study aims to answer the following research questions:

1. What are the effects of more explicit versus more implicit corrective feedback on learners’ perceptions of Mandarin tones?

2. What are the effects of more explicit versus more implicit corrective feedback on learners’ production of Mandarin tones?

3. What are learners’ and the instructor’s preferences for tone learning and corrective feedback?

METHODS

PARTICIPANTS

The participants were 41 adult learners of Mandarin who were all professionals planning on moving to China as an onward post in their current employment. Participants were enrolled in an online, module-based Mandarin course that required a weekly, 45- to 60-minute, video-chat session with a Mandarin instructor. Participants took part in either the spring 2017 or summer 2017 semester of the 14-week-long introductory Mandarin course designed specifically for professionals and their family members. All learners self-reported as having an ILR (Interagency Language Roundtable) score of either 0/0+ or 2 in Mandarin (equivalent to CEFR A1 and/or B2 proficiency levels).

All participants provided information about their background using a questionnaire administered pretreatment. Although the course was designed for absolute beginners, some participants indicated they had prior exposure to Mandarin. To balance the two experimental groups, participants were asked to indicate if they were a NS of a language other than English, if they had previously lived in a country where Mandarin was spoken, and if they had previously studied Mandarin. Participants were randomly divided into one of two different feedback conditions: a more implicit feedback condition and a more explicit feedback condition. There was no control group. Results from the questionnaire resulted in the following groupings (see Table 1).

TABLE 1. Participant biodata

No participants indicated they were a heritage speaker of Mandarin. Participants indicated they had previously studied other languages to varying degrees of proficiency. One participant identified another tonal language, Thai, as an L1. Previous research has shown small advantages for speakers of other tone languages, specifically Thai, in acquiring the tones of Mandarin (Li, Reference Li2016) as well advantages for Mandarin speakers in learning the tones of Thai (Wayland & Guion, Reference Wayland and Guion2004). However, the data from this participant was not determined to be an outlier according to an analysis of pretest and posttest boxplots and therefore this participant’s data was retained in the current study.

Participants’ previous experiences living in a country where Mandarin was spoken ranged from zero months (n = 35) to 1–3 years (n = 5) and was balanced between the two experimental groups (mean months living in China/Taiwan in the more implicit group = 2.3, more explicit group = 3.1). Previous exposure to Mandarin through classroom instruction ranged from 0 months (n = 30) to six semesters or 24 months (n = 1). Learners reported earning previous ILR scores in Mandarin of either level 0 or 0+ (n = 35) or level 2 (n = 6); however, they were not tested immediately prior to beginning the course and many reported attrited previous language skills.

The instructor and co-author of the study was a NS of Mandarin and bilingual in English with 7 years Mandarin teaching experience. The instructor had taught the SCMC course twice previously. Prior to treatment, the instructor participated in an hour-long training and piloting session in which she practiced providing the two types of feedback to a test student. In this pilot session, the instructor practiced delivering only explicit and then only implicit feedback to a pilot student reviewing course materials. During piloting, a researcher noted the instances of corrective feedback and the accuracy and consistency of the instructor’s delivery. The instructor and researcher then reviewed the results of the pilot session together.

MATERIALS

Pretests/posttests

To quantify changes in student’s perceptions and productions of tones after treatment, a pretest and equivalent posttest were designed and administered to the participants in both groups. All testing was conducted within the online platform where the course was hosted. The pretests and posttests both consisted of two parts: a tone perception test and a tone production test. In the tone perception test, the instructor read aloud sentences while participants saw the pinyin on an answer sheet (see supplementary materials). The sentences were read at a rate slower than natural speech leaving approximately 1 second between tones. Each sentence contained between and 9 and 18 tones for participants to identify. Sentences were adopted from historical Chinese poetry to reduce interference from participants’ background vocabulary knowledge (i.e., students were less likely to record the correct tone simply based on rote knowledge of a word-tone pairing rather than natural perception). The instructor read each sentence aloud while participants wrote down the tone of each word they heard on an answer sheet (with either tone symbols ˉ ´ ˘ `, or the corresponding numbers, 1, 2, 3, 4) containing the pinyin version of the sentences. Participants were not shown Chinese characters (see Figures 1 and 2 for student examples from the current study). The tones were distributed comparably between the pretest and posttest (126 total tones, 30 to 34 instances of each individual tone) over 9 and 10 test sentences in the pretest and posttest, respectively. The perception test took participants approximately 5 to 10 minutes to complete.

FIGURE 1. Example from perception pretest student answer sheet.

FIGURE 2. Example from perception pretest student answer sheet.

For the production portion of the test, participants saw pinyin with diacritics marking tones (not characters) that represented combinations of two to three characters. There were 25 items on the pretest and posttest representing 51 tones. Participants were asked to read the pinyin aloud while the instructor recorded their tone productions on an answer sheet. Items on the production test were obtained from levels 2 to 4 (intermediate to advanced levels) of the HSK (Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi) word list, a standardized vocabulary test for Mandarin learners (see supplementary materials). Learners would not have been previously exposed to these words in their course. The production portion of the tests took participants approximately 5 to 10 minutes to complete. All pretests and posttests were piloted with 40 intermediate-low university students studying Mandarin to test for ceiling effects and timing. All perception and production pretests and posttests were coded by trained raters. Interrater reliability was calculated as percent agreement.

Questionnaires and semistructured interviews

Prior to participation in the study, all participants completed an online background questionnaire. The questionnaire recorded basic biodata information about each participant including their age, gender, L1, and L2(s). They were also asked about their background in Mandarin including if they considered themselves a heritage speaker, if they previously lived in China, and if and how long they had previously studied Mandarin. The participants were also asked to respond to closed-ended questions about how they preferred to receive oral corrections after making an error: hearing back the corrected form or hearing an explanation of their mistake, and either immediately after making an error or after they had finished speaking. Finally, the questionnaire included open-ended questions that asked learners why they had enrolled in the course, what their learning and proficiency goals were, and any additional information about their preferences for oral correction (on any linguistic target).

Following the perception and production posttests, all participants individually took part in a semistructured interview concerning their perceptions of their own tone learning and preferences for corrective feedback. The instructor asked each participant to reflect on how they liked the corrections they received during the SCMC sessions. The posttest interviews took approximately 30 minutes to complete.

The semester following the final course, the course instructor participated in a semistructured interview (see supplementary materials for the interview protocol). The interview took 1 hour to complete. The instructor additionally kept ongoing field notes throughout the course of data collection. She retained notes during her SCMC sessions on students preferences about tone learning and their difficulties.

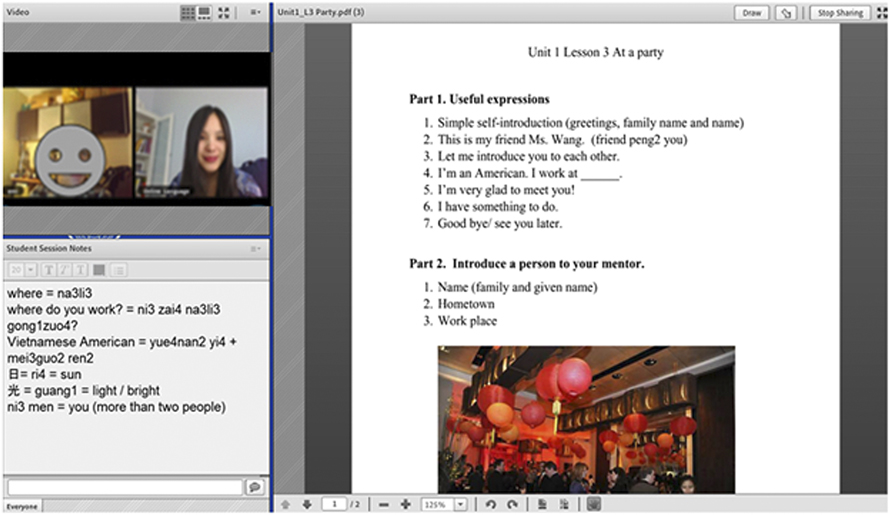

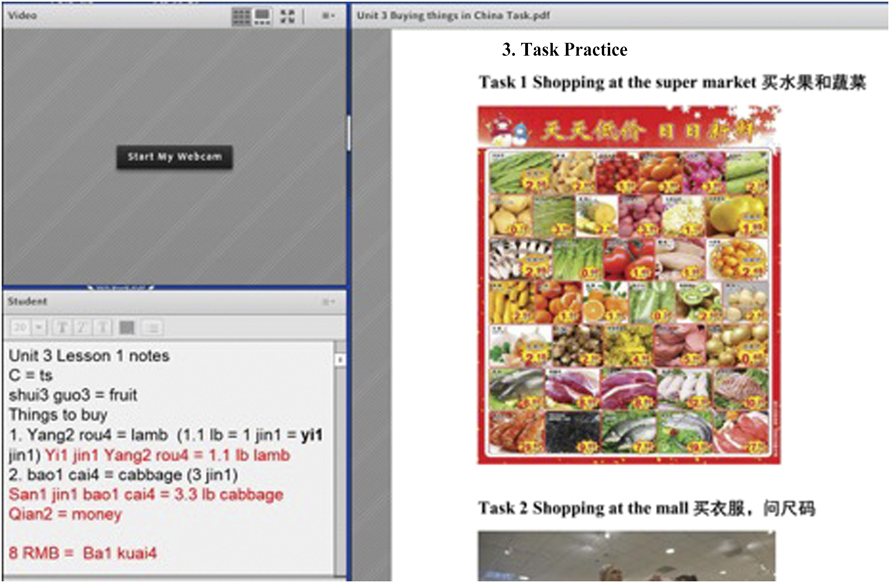

SCMC course

The course was hosted completely online in an eLearning platform designed and supported by participants’ employer. The participants navigated through the course independently, but were asked to spend between 6 and 8 hours per week studying the content. The 14-week, beginner-level course contained three units with one to four lessons per unit. Lesson objectives included understanding pinyin and characters; the four tones of Mandarin (both completed prior to pretesting); Chinese radicals; introductions; dates and time; locations and directions; food and drink; colors; stores and facilities; bargaining at the market; and household goods. Each unit included descriptions, tasks, and activities for learners to work through at their own pace. Each week participants spent 45 minutes to 1 hour reviewing the content and interacting with the instructor using Adobe Connect web-conferencing software. The instructor leveraged all materials available within the Adobe Connect system to teach the course. The Adobe Connect software included a video window, a text box, and a shared workspace where worksheets and other activities could be displayed and collaborated on in real time (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Online classroom environment.

Students were asked to come to the Adobe Connect SCMC sessions prepared to review content they had studied previously that week in the online modules through role plays and communicative tasks. The 45-minute weekly sessions were designed to be primarily interactive. Taking Unit 2 Lesson 2 Asking for Directions as an example, after briefly reviewing key vocabulary, the instructor and student would role play several scenarios in which the student needed to ask for directions and the instructor acted as a local NS and provided oral corrective feedback as needed. At the end of each task, the mentor provided feedback on overall task performance and reviewed content the student struggled with during task performance.

The instructor verified that learners completed at least 80% of the course content to pass the course. During the course, the instructor was based in the United States, while students completed the course from a variety of locations in the United States and abroad (but not from within any Mandarin-speaking contexts).

PROCEDURE

For both the spring and summer cohorts, in the second week of the course the participants took the perception and production pretests and background questionnaire. In the 11th and 12th weeks of the course (depending on absences, canceled classes, etc.), the students participated in the equivalent perception and production posttests and semistructured interviews (see Figure 4 for an overview of the procedure).

FIGURE 4. Procedure overview.

Prior to treatment the participants in both cohorts were initially divided randomly into two feedback groups: more implicit and more explicit feedback. The labeling recognizes that the explicitness of corrective feedback is a continuum and that feedback moves may be more or less explicit depending on the context of the interaction. Participants in both groups subsequently moved through the online modules of the course content at their own pace. Each week, participants had a 45- to 60-minute-long video-chat session with the instructor. During these SCMC exchanges the instructor would review content covered in the online modules, complete exercises, and provide feedback on student production. Both groups of participants engaged in the same content and the same number of SCMC sessions with the instructor for 14 weeks. During the sessions, both groups interacted in the online environment using the video-chat screen (this is where the oral corrective feedback was delivered) as well as through the shared workspace and the text-chat box. In the text-chat box, the instructor provided written feedback on grammatical forms, meaning, syntax, and individual phonemes (but never tones or any suprasegmental features). Written text-chat feedback on grammar errors prototypically took the same form for both groups: metalinguistic input and recasts to the correct form (see Figures 5 and 6 for examples). This was confirmed through an independently rated coding of a sample of 25% of the text-chat data, which showed that the majority of text-chat feedback targeted vocabulary (65.83%), morphosyntax (17.09%), and orthography (14.77%). No phonological feedback in any form was provided through the text-chat box. The oral feedback treatments were performed exclusively orally through interactive tasks.

FIGURE 5. Text-chat sample.

FIGURE 6. Text chat in SCMC learning environment.

All instructor SCMC sessions were digitally audio-recorded. The two groups differed only by the type of feedback provided by the instructor when the student made an error in their oral tone production during interactions.

In the more implicit feedback group, following a tone error the instructor provided an immediate recast with the correct tone and then paused to allow the participant to modify their output (see the following example from the data). After the student produced modified output the instructor provided a repetition of the correctly reformulated target tone or tones. In the event there were multiple tone errors in the student’s production the instructor broke the feedback into chunks by lexical item type (subject, verb, object) following suggestions from previous research that has indicated short or partial feedback is more effective at facilitating noticing than long or fully corrected feedback (e.g., Egi, Reference Egi2010; Loewen & Philp, Reference Loewen and Philp2006; Nassaji, Reference Nassaji2009; Philp, Reference Philp2003). For example, if a learner produced an utterance with six tones and errors on four tones, two on the subject and two on the verb, the instructor would break down her provision of corrective feedback into two chunks (see Example 2).

Example 2: Recast

In the more explicit feedback group, following a tone error the instructor immediately provided an explicit metalinguistic explanation of the error, pointing out which tone was incorrect and informing the student of the correct tone. She then paused and allowed the student the opportunity to modify their output (see Example 3) and provided a repetition of the correctly reformulated target tone or tones.

Example 3: Metalinguistic feedback

When students in the more explicit feedback group made multiple tone errors in a single utterance, the instructor provided chunked explicit feedback in the same way as previously described for the more implicit feedback group. In both experimental conditions, the instructor consistently paused following any type of feedback to allow students the opportunity to produce modified output. Occasionally, if the learner did not attempt to modify their own output the instructor would encourage them to do so by saying, “would you try that again?” or “would you try to say that word again?” This resulted in consistent modified output production across both experimental groups. An analysis of 10 hours of the data from a random selection of five sessions from the more implicit feedback group and five sessions from the more explicit feedback group revealed that the amount of tone feedback between the two groups was consistently provided with an average 17 provisions of tone feedback per session (range 10–23). Uptake (defined as corrected modified output) was also consistent between the two groups with an average of 12 modifications per session (range 9–22). In other words, 70% of feedback resulted in modified output in the coded sample in both groups.

ANALYSIS

To answer research questions 1 and 2—what are the effects of more explicit versus more implicit corrective feedback on learners’ perceptions/productions of Mandarin tones?—the pretests and posttests for both experimental groups were scored for accuracy and each participant received a raw test score. For the perception tests, the instructor scored the participants’ answer sheets by adding up the total number of tones marked correctly by the participant. Participants lost one point for every tone marked incorrectly as well as for leaving tones blank. In the perception pretest and equivalent posttest there were 126 tones with a range of possible scores from 0 to 126. For the production tests, the instructor scored participants as they read the pinyin combinations out loud. The participants received one point for every tone produced accurately and lost one point for every tone produced incorrectly. The production pretest and posttest contained a total of 51 tones resulting a possible range of scores from 0 to 51. Two trained, native Mandarin-speaking raters independently coded the entirety of the production and perception pretests and posttests and were in 100% agreement. Prior to analysis, the data was checked for normality by examining q-q plots and boxplots. This examination revealed two potential outliers in the posttest perception scores of both groups. Testing performed with and without outliers produced no significant changes; therefore, outliers have been retained for the following analysis. A mixed ANOVA tested for a significant interaction effect (a = .05) between test time and membership in the more implicit or more explicit feedback group. Significance testing and effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 20).

To examine research question 3—what are learners’ and the instructor’s preferences for tone learning and corrective feedback?—qualitative analyses were used to inform and follow up on the quantitative findings. Semistructured interviews, open-ended survey item responses, and instructor field notes were coded using a thematic, grounded approach. The resulting themes were then associated with relevant excerpts from the audio-recordings of interactions.

RESULTS

RESEARCH QUESTION 1

The first research question asked: “What are the effects of more explicit versus more implicit corrective feedback on learners’ perceptions of Mandarin tones?” It was expected that both groups would see improvement in their tone perception scores after 10 weeks of weekly hour-long SCMC sessions regardless of feedback type. Results indicated that both groups significantly improved their tone perception scores over the course of the 10 weeks. The main effect for time was statistically significant (F = 104.85, df = 1, p = .00) with an overall mean change of 34.74 points or 27.5% (M = 64.48 at time 1 and M = 99.23 at time 2) out of a possible 126 points. See Table 2 for an overview.

TABLE 2. Descriptive statistics for tone perception scores

Note: Total possible points = 126.

In terms of the two experimental groups, the more implicit group saw a mean gain of 38.14 points or 30.2% from pretest to posttest while the more explicit group saw a mean gain of 31.35 points or 24.8%. The main effect for experimental group was not significant (F = .986, df = 1, p = .327) and the interaction between time and experimental condition was not statistically significant (F = 1.00, df = 1, p = .323) and had a small effect (d = 0.54) (according to effect size benchmarks described in Plonsky & Oswald, Reference Plonsky and Oswald2014) (see Figure 7).

FIGURE 7. Change in tone perception scores.

RESEARCH QUESTION 2

The second research question asked: “What are the effects of more explicit versus more implicit corrective feedback on learners’ production of Mandarin tones?” It was expected that both groups would also see improvement in their tone production scores after 10 weeks of weekly hour-long SCMC sessions regardless of feedback type. Results indicated that both groups significantly improved their tone production scores over the course of the 10 weeks. The main effect for time was statistically significant (F = 90.22, df = 1, p = .00) with an overall mean change of 9.25 points or 18.1% (M = 32.09 at time 1 and M = 41.34 at time 2) out of a possible 51 points. See Table 3 for an overview.

TABLE 3. Descriptive statistics for tone production scores

Note: Total possible points = 51.

In terms of the two experimental groups, the more implicit feedback group saw a mean gain of 11.95 points or 23.4% from pretest to posttest while the more explicit feedback group saw a mean gain of 6.55 points or 12.8%. The main effect of group was not significant (F = 1.45, df = 1, p = .23). The interaction between time and group was statistically significant (F = 7.69, df = 1, p = .008) and had a medium effect (d = .75) (see Figure 8).

FIGURE 8. Change in tone production scores.

RESEARCH QUESTION 3

The third research question asked: “What are learners’ and the instructor’s preferences for tone learning and corrective feedback?” The results summarized here were gathered from a predata collection background questionnaire and postdata collection semistructured interviews as well as the instructor’s own field notes. Learners participated in both the background questionnaire and semistructured interviews while the instructor completed a semistructured interview based on her field notes.

Learner preferences

On the background questionnaire, completed prior to beginning the course, the majority of participants indicated that they preferred immediate explicit feedback upon making an error in Mandarin (80%, n = 33). When asked to further comment on their preferences for feedback on any type of error, these participants spoke to their initial desire for constant correction. One participant said: “I’d rather know when I’m making a mistake rather than ‘feeling good’ about my speaking.” Another said: “I appreciate constant feedback, regardless of good or bad,” while another encouraged the instructor to be “honest (clear/brutal/tough) with me … in particular push me to improve my pronunciation.” Only two participants’ responses indicated they preferred more implicit, meaning-driven feedback. One stated: “On how I like being corrected: if I am understandable, let me ‘roll with it’ so to speak” while the other deferred to the instructor: “I am fine with the instructor correcting me in whichever way they deem appropriate.”

Despite the majority of participants who indicated a preference for explicit corrective feedback, those in the more explicit feedback group during data collection often exhibited frustration with the type of feedback provided. A variety of learners in the more explicit feedback group stated in posttreatment interviews: “I couldn’t pay attention to every individual tone.... Hearing feedback on tones makes more nervous to use the language,” “I know the correct tones, but I can’t control myself,” and “I’m not good at this.” This indicated that the feedback learners received may have induced anxiety in some due to the overwhelming amount of errors being made in each utterance and that this potentially interrupted the learners’ processing of the feedback.

In the following example, a learner from the more explicit metalinguistic feedback group even suggests a more helpful form a feedback she thinks her instructor can try:

To be honest, I didn’t understand the tone feedback at the beginning. I focused on remembering the vocabulary and expressions. It might be helpful that you just repeat the correct tones back to me. It might be easier for you too.

This learner’s suggestion, while the most explicit example of a desire for the opposite type of feedback, underscores how the more explicit metalinguistic feedback learners in this group heard was potentially perceived as more salient than any following recasts. Additionally, these results indicated a potential mismatch between learners preconceived preferences for corrective feedback and tone learning and the reality they experienced with corrective feedback during the course. Despite indicating preferences for immediate feedback on all errors on surveys, learners later demonstrated a realization that other types of feedback could have been helpful as well.Footnote 1

Instructor preferences

Results from the instructor interview indicated a mismatch between the instructor’s initial beliefs about corrective feedback and tone learning and the outcomes of the study. When asked during her post-data-collection interview what the most effective form of feedback was, in her view, for her students’ tone perception and production learning, she stated that she found the final results of the study surprising:

At the beginning I did not know the answer. I thought metalinguistic one is better, because in English they don’t have tones so I they need to know the pattern.... At the end of the course I feel that the [more implicit] recast group is better because since there is no tone in English they don’t know what is rising or falling and they just need a lot of input and ... to know how to compare ... and how to pronounce it. At the end the [more implicit] recast group works better for beginners.

When asked what type of feedback was the easiest form to deliver to students in her view, the instructor stated that she preferred recasts over metalinguistic feedback due to the ease of delivery and the speed that it allowed to move on in her teaching. She stated: “You just pronounce it correctly and move on.” She indicated that explicit feedback became frustrating for students, especially when they made similar errors repeatedly. Some students who received explicit feedback would say, for example (according to the instructor): “I know, I know I should do low-dipping, but I cannot control myself!” This frustration affected her perceptions on what type of feedback was most appropriate for students. She explained, “Sometimes the emotion and impatience [of the students] can influence the teacher.”

In terms of the instructor’s perceptions of her own students, she said she found it interesting that so many students told her they wanted explicit explanations of their errors, she said: “A lot of students didn’t know that they really preferred recasts. A lot said they wanted more explanation: ‘please interrupt me I really appreciate your feedback I want all the details!’ In reality … they wanted to finish their sentences and … keep the conversation going.” She emphasized the variability in individual students’ personalities and how that interacted with feedback type. She said, “[S]ome students loved feedback no matter what you tell them, they would say ‘repeat it again’ and ask for [feedback] over and over”; these students were happy with any feedback provided. Other students seemed dissatisfied according to the instructor: “They got defensive ... when you try to give them feedback they wouldn’t modify their output ... some students didn’t pay attention.”

When the instructor was asked to interpret the quantitative outcomes of the study, she reiterated her surprise: “I think it’s a little bit surprising. I thought they [the explicit feedback group] have so much metalinguistic feedback, they should perform better!” The instructor explained her rationale for why there was an observed difference between the two groups at the end of the study: “I got a feeling the [more implicit] group didn’t have a time lag that the [more explicit] group did and they could repeat back so quickly, for metalinguistic they have their attention drawn to certain things ... and they might forget how they pronounced it, and they can’t identify the gap between my pronunciation and theirs.” She indicated that her perception was connected with the proficiency level of the learners. Given that her students were low-beginners, she stated she felt the more explicit feedback increased student anxiety. She said, “[T]one is so new to them you don’t want to add extra pressure to their learning.”

DISCUSSION

The primary goal of the current study was to examine the effects of more explicit versus more implicit oral corrective feedback on L2 Mandarin tone perception and production after 10 weeks of SCMC interactions with an instructor. The secondary goal was to investigate student and instructor perceptions and preferences concerning their tone learning and the corrective feedback they received throughout the course. The results from the perception pretests and posttests indicated no statistically significant difference between the more implicit (recast) feedback group and the more explicit (metalinguistic) feedback group from pretesting to posttesting (F = 1.00, df = 1, p = .323) with a small effect (d = 0.54). However, the mean gain was descriptively larger for the more implicit feedback group (38.14 mean points gained out of 126) than the more explicit feedback group (31.35 mean points gained). The results from the production pretests and posttests demonstrated a significant interaction (F = 7.69, df = 1, p = .008) with the more implicit group gaining an average of 11.95 points between pretest and posttest (out of a possible 51) and the more explicit feedback group gaining an average of 6.55 points with a medium effect (d = .75). Additionally, the standard deviation of the production posttest scores for the more implicit feedback group were notably smaller (4.93) than their pretest scores (8.3) and smaller than both the pretest and posttest scores of the more explicit feedback group (9.93 and 9.17, respectively). This indicates that participants’ scores at pretesting had greater variability and this variability continued at posttesting for those in the more explicit feedback group but not the more implicit feedback group. Given that models such as Flege’s (Reference Flege and Strange1995) would predict gains in production following from gains in perception abilities, more evidence is needed to untangle the relationship between perception and production of nonnative tone found in the current study.

From an interactionist perspective, these results are in line with previous research that has shown that more implicit feedback is more effective when targeting aspects of L2 phonology (Mackey et al., Reference Mackey, Gass and McDonough2000; Saito & Lyster, Reference Saito and Lyster2012) as well as findings that suggest that more implicit feedback is more effective with meaning-bearing items (such as lexical tone) as opposed to unessential or nonsalient forms (Long, Reference Long2007). Implicit feedback such as recasts may also be more effective for linguistic forms that are relatively difficult to learn and require long-term treatments like the Mandarin tones examined in the current study (Goo & Mackey, Reference Goo and Mackey2013) which are not easily mastered until high levels of proficiency. However, as some have pointed out (e.g., Gottfried & Suiter, Reference Gottfried and Suiter1997; Wong & Perrachione, Reference Wong and Perrachione2007), highly proficient L2 Mandarin speakers often are able to communicate successfully despite difficulty in accurate lexical tone production due to the fact that Mandarin tones are often semantically redundant in certain contexts. Therefore, these results may not hold for advanced learners interacting in naturalistic communicative situations.

The results found in the current study demonstrate a potential contrast to findings that have suggested implicit feedback such as recasts are better suited for more advanced learners whose developmental readiness allows for a higher sensitivity to the input (Ammar & Spada, Reference Ammar and Spada2006)—this was the belief of the instructor prior to the onset of the study. Future studies should explicitly examine proficiency as a factor to better understand the interplay between the efficacy of different types of feedback and proficiency levels. These findings are also in contrast to studies that have shown groups who receive metalinguistic feedback outperform those that receive recasts (Ellis, Reference Ellis and Mackey2007; Ellis, Loewen, & Erlam, Reference Ellis, Loewen and Erlam2006; Sheen, Reference Sheen and Mackey2007). In the current study, the low proficiency learners who had, in general, little to no previous exposure to the target structure benefited more from implicit feedback (for tone production) than from explicit metalinguistic feedback. An examination of quantitative results in conjunction with the results from the qualitative data (interviews, surveys, and field notes) shed further light on these findings. The instructor of the course highlighted the immediacy of the juxtaposition of positive evidence (the recast) with negative (the learner’s error) as a favorable site for learning that was lost when metalinguistic explanations were included, a feature of recasts that has been pointed out in a variety of previous work (Goo & Mackey, Reference Goo and Mackey2013; Leeman, Reference Leeman2003; Long, Reference Long2007; Long & Robinson, Reference Long, Robinson, Doughty and Williams1998). Long (Reference Long2007) adds that because recasts happen in context without interrupting the flow of meaning making they enable a “joint attentional focus” between interlocutors that increases motivation and facilitates noticing (pp. 77–78). The instructor highlighted this in her interview when she described her perceptions of the learning in the more explicit feedback group: “they have their attention drawn to certain things” pointing out how students who received metalinguistic feedback had their attention drawn away from their own output and were no longer (according to the instructor) able to “identify the gap between my pronunciation and theirs.” This reflection highlights the utility of the immediate juxtaposition of error and correction provided by recasts. Furthermore, the instructor perceived that more explicit feedback added “extra pressure” on some students already struggling with tone acquisition, noting that some learners seemed to become frustrated by the metalinguistic corrections, as demonstrated by their interview responses. These findings suggest that individual differences potentially played a role in the learners’ experiences with corrective feedback. Anxiety (Sheen, Reference Sheen2008) attention and attentional control (e.g., Goo, Reference Goo2012), working memory (e.g., Li, Reference Li2013; Mackey et al., Reference Mackey, Philp, Fujii, Egi, Tatsumi and Robinson2002), and developmental level (Mackey et al., Reference Mackey, Philp, Fujii, Egi, Tatsumi and Robinson2002) have all been shown to mitigate the effects of corrective feedback highlighting the complex relationship between learner individual differences and acquisition. For example, a study by Mackey et al. (Reference Mackey, Philp, Fujii, Egi, Tatsumi and Robinson2002) found that learners with high phonological short-term memory at lower developmental levels report more noticing of feedback than those at higher developmental levels. However, a study by Li (Reference Li2013) linked working memory to explicit feedback, suggesting learners who have high working memory are better able to memorize facts presented in metalinguistic feedback, but in the absence of metalinguistic information, learners with higher analytic abilities achieve more (Li, Reference Li2013). Without an investigation of the individual working memory capacities or analytical abilities of the students in the current study it is impossible to make any claims. However, it is worth noting the occurrence of individualized responses to feedback throughout the dataset that could have contributed to the findings. There is clearly a need for further study of the potential effects individual differences have on Mandarin tone acquisition.

Finally, the results from research question 3 indicated that there was a mismatch between learner preferences for corrective feedback and developmental outcomes. The majority of students indicated on the background questionnaire that they preferred explicit, immediate corrective feedback on their tone errors, a preference often exhibited in language learners (e.g., Jean & Simard, Reference Jean and Simard2011). However, the quantitative findings demonstrated greater outcomes for the group that received more implicit feedback. Additionally, the instructor reported instances of students who received more explicit feedback growing frustrated. When asked to compare the two forms of feedback at the end of the study, the instructor highlighted the ease of delivery of more implicit over more explicit feedback, a tendency found in face-to-face classroom research as well (e.g., Brown, Reference Brown2016). Of note is the fact that the instructor changed her perspective from the beginning to the end of the course, from a belief that explicit feedback on tones was best for her learners, to finding implicit feedback on tones to be most effective for her context. While these findings may not be equitable with the perceptions of an instructor who has not been explicitly taught about two potentially contrastive feedback types, these findings do echo previous research (e.g., Kaivanpanah, Alavi, & Sepehrinia, Reference Kaivanpanah, Alavi and Sepehrinia2015; Vásquez & Harvey, Reference Vásquez and Harvey2010) demonstrating mismatches between learner and teacher preferences and L2 outcomes. Future research should more closely examine the changes that occur in feedback preferences by instructors and learners as their awareness of the realities of corrective feedback in their particular context increases.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

There are several limitations of the design and methodology that should be taken into consideration when reflecting upon the results reported in the preceding text. First, due to the limited size and scope of the participant sample it is not possible to generalize the results of this study to all types of learners. The learners in this study were all adults and all enrolled in the course for professional purposes (moving to China for work), meaning they are a self-selected, highly motivated group who have chosen a career path of learning multiple languages and living in and experiencing different cultures. Some of the learners in the current study were enrolled as part of their job duties, or because they wanted to bid on a future job posting in a Mandarin-speaking country (however, the participants also included spouses who may have had other motivations for language learning). Their experience of learning Mandarin tones thus may be qualitatively different than other types of learners especially, for example, younger learners or students studying Mandarin in a college course whose motivations and attitudes may differ (e.g., Kormos & Csizér, Reference Kormos and Csizér2008). Future studies with more learners could compare the outcomes of tone learning with language learning motivations or attitudes. Additionally, although no students in the current study were actively enrolled in any other Mandarin courses, the online nature of the course meant it was impossible to control outside exposure to Mandarin. It is possible that students were exposed to Mandarin, and possibly other forms of corrective feedback from outside sources. Furthermore, there were cases in the data in which a student explicitly requested an alternate form of feedback. This potential confound only occurred occasionally throughout the entire dataset, and the instructor took care to mitigate these situations by repeating the previously provided feedback. However, the possible exposure to other types of feedback other than the one assigned to the group is a potential threat to the study’s validity. Future, more experimental, studies could mitigate this limitation by debriefing students prior to the onset of the study about the type of feedback they are assigned.

An additional limitation of the study was the absence of a control group that received no corrective feedback. Although this was due to authentic nature of the study in which an instructor could not ethically withhold all feedback from a set of learners, the lack of a control group means that the results of this study should be interpreted with caution as it is difficult to attribute the results exclusively to the type of feedback and eliminate all other variables that could have contributed to the observed improvements in tone perception and production. While the authentic classroom context adds ecological validity to the study, a future study with tightly controlled experimental conditions, such as in a laboratory, could mitigate these limitations. The classroom context and tight course schedule also precluded the possibility of following up on gains with delayed posttests. Future studies should include delayed posttests as they can determine whether the effects of interventions are durable or fade in subsequent weeks (see Mackey & Goo, Reference Mackey, Goo and Mackey2007). Additionally, due to limitations set by the administrators of the online course, only the instructor was able to interact with the students and therefore was the interviewer and tester of her own students. While there are possible advantages to leveraging the trust built between students and their instructor over the course to encourage more honest responses, this could have also led to social desirability bias on the part of the participants.

Participants in the current study participated in controlled pretests and posttests as a measure of their tone perception and production development. While a controlled test allows for construct and testing validity, unlike task-based assessments, they may not translate similarly to accurate tone performance in tasks or in authentic communicative contexts. Future studies could include task or communicatively oriented tests to examine whether corrective feedback conditions translate to more successful task-based interactions.

In terms of the procedure for the current study, only two extreme types of feedback were examined: more implicit and more explicit feedback. In the reality of language classrooms, teachers may utilize a variety of feedback types and it is so far unknown how variations on feedback types could affect the results of the current study. Other often-studied feedback types include clarification requests, confirmation checks, prompts, and repetitions. While these additional forms of corrective feedback have been studied to various degrees (see Mackey, Reference Mackey2012 for an overview), little is known about how the variety of feedback options could be profitably applied to Mandarin tone learning. Future studies should include additional groups for a finer-grained analysis of the efficacy of various feedback strategies.

Individual student differences, which were not accounted for in the current study, could be both a limitation and an avenue for further investigation. As described previously, the instructor’s impression of her students was that some seemed more motivated to produce modified output while others lamented their lack of tone learning skills. Individual learners’ propensity to produce modified output was not accounted for in the current study and should be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings. Future studies could examine the role of uptake, such as noticing of feedback, and rates of modified output or repair, which could bolster claims about the effectiveness of different types of feedback. Other individual differences such as phonological working memory and phonological awareness (Wong & Perrachione, Reference Wong and Perrachione2007), musical ability (Li & DeKeyser, Reference Li and DeKeyser2017), and perceptual abilities (Cooper & Wang, Reference Cooper and Wang2013) have all been linked to success in L2 tone-word learning. Moreover, working memory has been shown to mediate the effects of implicit but not explicit corrective feedback (Goo, Reference Goo2012) suggesting that executive attention plays a role in the noticing of implicit feedback such as recasts, but not a role in the noticing of metalinguistic feedback. In the current study, findings demonstrated an advantage for Mandarin tone production when participants received more implicit feedback as opposed to explicit metalinguistic feedback on their tone errors while no significant difference was found for tone perception between the two groups. To further untangle these results, individual differences could be accounted for in future studies and findings could be interpreted with an eye to how mediating factors such as motivation, working memory, and musical ability affect gains in tone perception and production.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263119000317