Marginalisation among young people is a major concern for policymakers in many countries,1 as it is linked to both individual suffering and costs for society. Preventing marginalisation, and identifying it at an early stage, are important for public health and the economy. Psychiatric disorders have been identified as one of the factors associated with marginalisation or social exclusion,Reference Morgan, Burns, Fitzpatrick, Pinfold and Priebe2 although being employed is an essential part of recovering from psychiatric disorders. Apart from providing financial independence, having a job can provide an individual with structure and purpose to their life and a social role without stigma.Reference Rinaldi, Killackey, Smith, Shepherd, Singh and Craig3

Although there is no unique definition of social exclusionReference Morgan, Burns, Fitzpatrick, Pinfold and Priebe2 or marginalisation, not being in education, employment or training (NEET) has been widely used as an indicator by policymakers.1 The term NEET was first used in the UK at the end of the 1990s and was rapidly adopted by organisations across the globe. For example, the European Union uses NEET levels, defined as the proportion of young people who report as NEET during a certain week, to measure how many young people are at risk of becoming socially excluded. Being NEET for a week could be called short-term NEET, and it is common: 12.0% of people between 15 and 24 years of age in the EU were NEET in 2015.1 Being NEET for a week was also associated with psychiatric disorders in a Canadian cross-sectional study.Reference Gariépy and Srividya4 Other definitions of labour market marginalisation have also been linked to certain psychiatric disorders, including being unemployed, on sick-leave or receiving disability pension or welfare support. These include mood disorders, anxiety, psychosis, substance misuse, neuropsychiatric disorders, behavioural disorders and traits of personality disorders.Reference Gjerde, Røysamb, Czajkowski, Knudsen, Ostby, Tambs and Kendler5–Reference Upmark, Lundberg, Sadigh and Bigert14 Furthermore, a systematic review has reported well-established associations between mental health problems in adolescence and lower educational attainment.Reference Esch, Bocquet, Pull, Couffignal, Lehnert and Graas15 However, there have not been any follow-up studies on the association between diagnosed psychiatric disorders and not being in education or employment for several years, which we term long-term NEET. Consequently, the association between psychiatric morbidity and more persistent exclusion from the labour market has not been addressed. The primary aim of this study was to carry out a comprehensive overview of the associations between different psychiatric illnesses and long-term NEET, which was defined as not being engaged in education, employment or training for at least 5 years. We chose to study long-term NEET, rather than being NEET for a short time such as 1 week, because it is a more severe marker of labour market marginalisation.

Method

Study design

We used data collected for the 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort study, which has been described in detail elsewhere.Reference Gyllenberg, Marttila, Sund, Jokiranta-Olkoniemi, Sourander and Gissler16 This longitudinal study is managed by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare and contains extensive data from Finnish nationwide registers for all children born in the country in 1987. This cohort study received approval from the Institute's review board. We also received permission from the registered keepers of the various data sources used in this study, as required by Finnish law. All data were anonymised prior to the analyses and handled according to Finnish data protection legislation and regulation. Informed consent was not required because none of the individuals included in the study were contacted.

The cohort comprised data on 59 476 people who were born in 1987. We excluded individuals who had lived outside Finland during the study period, died before the end of 2015 or had a diagnosis of intellectual disability.

Definitions of outcomes

Long-term NEET was defined as meeting none of the following criteria for at least 5 years between 2008 and 2015: working, studying, being on parental leave or taking part in jobseekers’ programmes. The cohort members were all 20–28 years old at the time. Being employed was defined as getting any salary that contributed to a pension scheme. Being in education was defined as receiving any student benefits. Finnish citizens can get student benefits if studying is their main occupation and they are progressing in their studies. Parental leave was defined as receiving childcare benefits.

Predictors

The main predictors were psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders diagnosed by specialist services between 1998 and 2007, when the cohort members were 10–20 years old. That age range was chosen because out-patient data were available from the year 1998 onwards, when the children born in 1987 turned 11 years old. Only in-patient data were available before that date. The diagnoses were recorded according to ICD-10. They were categorised into diagnostic entities in line with previous reportsReference Gyllenberg, Marttila, Sund, Jokiranta-Olkoniemi, Sourander and Gissler16 and are described in detail in supplementary Table 1, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.146. One person could have several different diagnoses. We also separately examined psychiatric in-patient care with a psychiatric main diagnosis.

Socioeconomic background factors

The potential covariates were derived from registers and we chose background factors that had already been associated with adolescent psychiatric disorders and labour market marginalisation in previous studies.Reference Merikukka, Ristikari, Tuulio-Henriksson, Gissler and Laaksonen9,Reference Sutela, Törmäkangas and Toikka17 We considered three childhood socioeconomic factors: low parental education level and whether, before 2005 (when the participants turned 18), the parents had received any welfare benefits or had been admitted to hospital with a severe mental disorder. Parental education was divided into three categories and based on the highest category for either parent: just compulsory education; completed upper secondary education; received a university degree. We also examined two background factors for the participants: gender and whether they had completed upper secondary education by the end of 2008.Reference Sutela, Törmäkangas and Toikka17

Description of the registers

Data from different sources were linked to each individual using the unique personal identification code that is assigned to Finnish citizens and permanent residents in the Central Population Register. Data from eight registers were used for this study. The Medical Birth Register identified the individuals’ mothers and the Care Register for Health Care provided diagnoses from public specialist services. Statistics Finland determined whether any of the individuals had died and the level of education that their parents had attained. The Central Population Register identified emigration data and individuals’ fathers. The Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare provided data on welfare benefits, the Finnish Centre for Pensions provided data on salaries and childcare benefits and the Social Insurance Institution of Finland provided data on student benefits. The Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment Register provided information about participation in jobseekers’ programmes. The registers have been described in detail elsewhere.Reference Sund18

Information on diagnoses of psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders were obtained from the Care Register for Health Care and these were recorded during visits to in-patient units or out-patient clinics in public hospitals across Finland. There are no private paediatric or psychiatric hospitals in Finland, so this source provided comprehensive data. The records are continuously gathered and regularly submitted to the register by the Finnish hospital districts. They included the start and end dates of any visits, a mandatory primary diagnosis and optional secondary diagnoses. The register contains in-patient data since 1969 and out-patient data since 1998. This register has been widely used for epidemiological researchReference Sund18 and the diagnostic validity of various mental disorders in it has been studied (e.g. autismReference Lampi, Sourander, Gissler, Niemelä, Rehnström and Pulkkinen19 and schizophreniaReference Pihlajamaa, Suvisaari, Henriksson, Heilä, Karjalainen and Koskela20).

Statistical methods

Logistic regression was used to quantify the association between psychiatric disorders in adolescence and long-term NEET in early adulthood. First, we used univariate models to study each predictor separately. Second, we examined the independent effects of the disorders by using multivariate models that comprised each category of diagnosis and the relevant covariates. We conducted two separate multivariate analyses: one that included parental factors and gender and one that included completing upper secondary education.

Sensitivity analyses were also used to separately examine those who had, or had not, finished upper secondary education before the end of 2008, by the age of 21. This was used as a proxy for any problems with continuing education. We added an extra 2 years to account for late starters, people studying at a slower pace and people who took a gap year. To examine the potential effect of overlapping diagnoses, we initially examined the cohort by excluding those with a substance use disorder. Then we excluded those with a diagnosis of psychosis or autism spectrum disorder. We also carried out detailed post hoc explorations of the two diagnostic groups with the highest ORs for long-term NEET, based on ICD-10 diagnostic codes (see supplementary Table 1). For autism spectrum disorder, we examined infantile autism, Asperger syndrome and other types of autism spectrum disorder. Those who had been diagnosed with psychosis were split into three groups: schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and other kinds of psychosis.

For autism spectrum disorder and psychosis, we also counted the population attributable fraction (PAF) as (incidencepopulation – incidenceunexposed)/incidencepopulation, and the number needed to be exposed (NNE) as 1/(incidenceexposed – incidenceunexposed). Finally, as the definition of long-term NEET was novel, we also analysed associations between psychiatric diagnoses and NEET status for at least 1 year and at least 3 years. We used R statistical software, version 3.4.0 for Windows (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) for our analyses.

Results

Participants and setting

The 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort study includes 59 476 people who were born in Finland and survived the perinatal period. Of these, 756 (1.3%) died before the end of follow-up during 2008–2015, when participants were 20–28 years of age. Another 2913 had emigrated and 534 were diagnosed with intellectual disability. The final number included in the analyses was 55 273 (51.5% male), which was 92.9% of the original birth cohort.

Long-term NEET status

One in six of the included cohort members (9199; 16.6%) had been outside employment, education and training for at least 1 year. However, only 1438 (2.6%) had been long-term NEET for at least 5 years (supplementary Fig. 1a). The percentage that had been NEET increased towards the end of the 2008–2005 follow-up (supplementary Fig. 1b).

Sociodemographic characteristics

The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. We looked at the 1438 individuals who had been long-term NEET during 2008–2015, when they were 20–26 years of age. This showed that by the end of 2008, 65.1% of those who were long-term NEET were male and 65.0% had not successfully completed their upper secondary education. Among those who did not complete upper secondary school, 10.0% (n = 935/9339) were later long-term NEET. Analysing the parents of the 1438 individuals who were long-term NEET showed that 13.5% had a low level of education. In addition, 55.4% had received welfare support and 21.3% had been treated in hospital for a psychiatric disorder before their child was 18 years of age. All associations between sociodemographic factors and long-term NEET status were statistically significant (P < 0.001), and not having finished upper secondary education showed the highest effect size (OR = 10.1, 95% CI 9.0–11.2).

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics and long-term ‘not in education, employment or training’ (NEET) status

Associations between diagnosed psychiatric disorders and long-term NEET

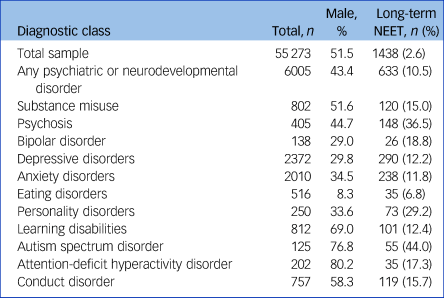

Table 2 shows that 6005 (10.9%) cohort members had been diagnosed with a psychiatric or neurodevelopmental disorder between 1998 and 2007, when they were 10–20 years of age (defined here as adolescence). Of these, 43.4% were male. Of the diagnostic categories, only substance use disorders, the neuropsychiatric disorders and conduct disorders were more common among male participants than females.

Table 2 Psychiatric disordersa diagnosed in adolescence and long-term ‘not in education, employment or training’ (NEET) status

a. For classification of disorders see supplementary Table 1.

Of the 1438 cohort members who were long-term NEET in young adulthood, 633 (44.0%) had been diagnosed with a psychiatric or neurodevelopmental disorder in adolescence. The most common diagnoses in those who were long-term NEET were depressive disorders (20.1%), followed by anxiety disorders (16.6%). The diagnostic groups with the largest proportion of individuals with long-term NEET status in young adulthood were autism spectrum disorder (44.0%) and psychosis (36.5%).

In the univariate analysis, the OR for the association between any psychiatric or neurodevelopmental diagnosis in adolescence and long-term NEET in young adulthood was 7.1, with a 95% confidence interval of 6.4–7.9. When the covariates of parental education, welfare support and severe mental illness and the participants’ gender were included, the OR was only moderated to 6.7 (95% CI 6.0–7.5). It was further moderated to 4.2 (95% CI 3.8–4.8) when we included whether or not the participants had completed upper secondary school education. The ORs of the specific diagnostic categories are summarised in Fig. 1, with further data in supplementary Table 2. The highest effect sizes for long-term NEET in the full multivariate models were for autism spectrum disorder (OR = 17.3, 95% CI 11.5–26.0) and psychosis (OR = 12.0, 95% CI 9.5–15.2). The associations were statistically significant for all diagnostic categories (P < 0.001).

Fig. 1 Psychiatric or neurodevelopmental diagnoses in adolescence in relation to long-term ‘not in education, employment or training’ (NEET) status in young adulthood.

Results are shown separately for univariate and multivariate analyses with the following sociodemographic characteristics included as covariates: parental education, parent received welfare support, parent with severe mental illness, and participants’ gender or the previous and not having successfully completed upper secondary education. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are presented on a logarithmic scale. The diagnostic categories are ranked by the OR of univariate associations. All associations are statistically significant at P < 0.001. See Tables 2 and 3 for the covariates in each model.

Because of the large effect size between not having finished upper secondary education and NEET status, we conducted separate analyses on those who did, and did not, reach this level of education before the end of 2008 (Table 3). Among those who did not complete their upper secondary education, 70.6% of those with autism spectrum disorder and 48.4% of those with psychosis were later long-term NEET. Furthermore, the associations with long-term NEET were statistically significant for all diagnostic categories both for those who had completed upper secondary education and for those who had not (all P < 0.001).

Table 3 Psychiatric disordersa diagnosed in adolescence and long-term ‘not in education, employment or training’ (NEET) status in those who had and had not finished upper secondary education

a. For classification of disorders see supplementary Table 1.

Additional analyses

We examined psychosis and autism spectrum disorder in more detail as these were the two diagnostic groups with the highest ORs for long-term NEET. These results were in line with the main results (supplementary Table 3). To study whether highly specified diagnoses changed the main results, we excluded those with infantile autism. Long-term NEET remained similar for Asperger syndrome in the univariate analysis (OR = 29.4, 95% CI 18.5–46.2, P < 0.001) and for other autism spectrum disorder when we excluded both infantile autism and Asperger syndrome (OR = 21.3, 95% CI 10.5–41.6, P < 0.001). Similarly, when individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were excluded, the association between long-term NEET and other kinds of psychosis remained similar (OR =14.5, 95% CI 11.1–18.9, P < 0.001). Further, if a causal relationship could be assumed between these diagnoses and long-term NEET, the population attributable fraction (PAF) and number needed to be exposed (NNE) would be of interest. The PAF was 3.6% for autism spectrum disorder and 9.6% for psychosis, and the NNE was 2 for autism spectrum disorder and 3 for psychosis.

Our main analyses included out-patient and in-patient diagnoses between 1998 and 2007, when our participants were 10–20 years of age. We also compared the psychiatric main diagnoses for just in-patient care between 1987 and 1997, when they were 0–10 years of age, as out-patient data were only available from 1998. In the univariate analysis, the OR for long-term NEET for in-patient treatment at 0–10 years of age was 7.3 (95% CI 5.9–9.1, P < 0.001). The OR for in-patient treatment at 10–20 years was 11.5 (95% CI 10.1–13.0, P < 0.001) (supplementary Table 3).

As previous studies only defined NEET status for shorter periods than 5 years, we analysed associations for NEET status for over 1 year and for over 3 years. All the associations were statistically significant, as they were in the main analyses, but the ORs were lower when NEET was defined for over 1 or over 3 years than for 5 years or more (supplementary Fig. 2).

Finally, because cohort members could be diagnosed with multiple disorders during adolescence, we re-ran the analyses by leaving out individuals who had been diagnosed with either a substance use disorder, psychosis or autism spectrum disorder. The associations with long-term NEET remained statistically significantly for all other diagnostic categories (supplementary Fig. 3).

Discussion

Our main result was that being diagnosed with psychiatric disorders in adolescence strongly predicted long-term NEET in early adulthood, regardless of whether individuals had completed upper secondary education or not. Family background did not affect the associations to any substantial degree. The diagnostic groups with the highest prognostic values were psychosis and autism spectrum disorder, with over one-third being long-term NEET in early adulthood. Finally, adolescents with both a psychiatric diagnosis and no upper secondary education faced a high risk for long-term NEET. In this group, almost three-quarters with autism spectrum disorder and just under a half with psychosis were long-term NEET. These results have implications for identifying adolescents who are receiving psychiatric treatment and need educational support, social services and work rehabilitation.

The association between all psychiatric diagnostic categories and long-term NEET could be explained by social selection theory, which looks at what health problems have an impact on an individual's socioeconomic position.Reference Chen and Kaplan21 This might happen when individuals find themselves in a low socioeconomic position because of poor health or health-related expenses. Alternatively, it might lead to a decreased accumulation of human capital, which is the skills, education and capacity an individual has. Low levels of human capacity can result from poor health during critical periods in childhood and adolescence.Reference Haas, Glymour and Berkman22 The rival theory to the social selection model is the social causation model, which states that low socioeconomic status leads to poverty and other forms of disadvantage, which in turn affect mental health.Reference Hammarström and Janlert23 We did not specifically test for the social causation model nor other more complex patterns of socioeconomic and psychiatric events. However, it is of note that psychiatric disorders diagnosed in specialist services independently predicted long-term NEET, regardless of the studied sociodemographic risk markers.

Almost half of the young adults who were long-term NEET had been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder when they were adolescents. The quality of work rehabilitation services, and the design of disability benefits, are likely to affect people with psychiatric disorders who manage to continue their education and find employment.Reference Charette-Dussault and Corbière24 The evidence-based individual placement and support model for vocational rehabilitation has shown significantly better outcomes for young adults than traditional rehabilitation for that age group.Reference Bond, Drake and Becker25 Those who have not finished their studies need support to return to or continue their studies. More research is needed on the best ways of ensuring that young people with mental disorders can finalise their studies.

Earlier studies have shown that the women in this cohort are educated to a higher level than the men, but there are no major differences in the main occupation.Reference Sutela, Törmäkangas and Toikka17 We found that more men had long-term NEET status than women. Among those diagnosed with psychiatric disorders who also were long-term NEET, the proportion who were male was smaller than in the full cohort of those who were long-term NEET. This could be explained by the fact that more women had been diagnosed with psychiatric disorders.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this nationwide study was that it covered all Finnish people born in 1987 and followed them up until the age of 28 years. We were able to establish links between an exceptionally large number of register-based data entries. This enabled us to use a comprehensive definition of marginalisation, have a long follow-up period and consider a number of sociodemographic characteristics.

The following limitations should be considered. Only diagnoses made by specialist services could be analysed. The diagnostic validity of, for example, autismReference Lampi, Sourander, Gissler, Niemelä, Rehnström and Pulkkinen19 and schizophreniaReference Pihlajamaa, Suvisaari, Henriksson, Heilä, Karjalainen and Koskela20 in the Care Register for Health Care have been shown to be good, but the diagnostic validity of all mental disorders in the register has not been studied. Out-patient data were available from 1998 onwards, when the children born in 1987 turned 11 years old. This means that we had high-quality data on disorders treated during adolescence. However, the number of diagnosed neurodevelopmental disorders that we identified might have been smaller than it should have been, if these were only treated in childhood. On the other hand, individuals whose lives were still considerably affected by neurodevelopmental disorders in adolescence would probably have visited a doctor in specialist care services at some point.

Our definition of the outcome of long-term NEET is novel and should be reassessed in other countries and settings for generalisability. Previous studies have relied on questionnaires or register-based data of just one factor that resulted in individuals being marginalised from the labour market. We used several registers to minimise the risk of including false-negative cases of NEET. Finnish administrative registers provide very high data coverage and they enabled us to assess NEET over a long follow-up period, as they do not suffer from attrition bias. It is important to note that work rehabilitation was not regarded as being part of the labour market. The results were similar when we compared those who had been NEET for at least 1, 3 or 5 years, but the effect size between NEET and psychiatric disorders was higher the longer the NEET status had lasted. Although the registers contained information on several covariates related to marginalisation, we lacked information about protective factors and resilience. However, being able to use this number of registers was exceptional. Finally, exact generalisations to other countries should be avoided, owing to differences in health and rehabilitation services, social benefits and labour markets.

Implications

Our finding of clear associations between main psychiatric diagnoses in adolescence and long-term NEET in young adulthood suggests that effective adolescent mental health services, including prevention, early intervention, social services and vocational rehabilitation, should be considered as important elements in a strategy to tackle young people's marginalisation. Combining inclusive and targeted strategies could reduce individual suffering and the costs to society of long-term NEET. The results of this study can function as a baseline if the number of young people who are marginalised or suffer from psychiatric disorders increases after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.146.

Data availability

Individual-level register-based data cannot be freely shared owing to Finnish legislation.

Author contributions

I.R. conducted the literature search, prepared the figures and tables, planned the data analysis, analysed the data, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. J.S. planned the study, interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. A.K. planned the data analysis, interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. M.G., T.R. and A.S. interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. D.G. planned the study and the data analysis, interpreted the data, prepared the figures and revised the manuscript.

Funding

The 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort study was funded by the Academy of Finland (grant 288960). The study is also part of the PSYCOHORTS and INVEST consortia, funded by the Academy of Finland (grants 320162, 308552). D.G. has received funding from the Academy of Finland (grant 297598). The funders had no role in designing the study, collecting, analysing and interpreting the data, writing the report or the decision to submit the paper.

Declaration of interest

I.R. reports non-financial support from H. Lundbeck A/S outside the submitted work.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.