‘Informed consent is a process, not just a form’,1 although often heard, in the actual practice of clinical trials is this statement merely an empty platitude? How should it be actualised in longitudinal research? These questions are of particular importance in clinical trials for psychotic disorders which, by their very nature, may be associated with fluctuations in mental coherence. Moreover, disease-related variables, such as medication adjustment or withdrawal may acutely exacerbate symptoms and impair mental status.Reference Jeste, Palmer and Harris2 Mental status fluctuations, in turn, may adversely affect a person's capacity to monitor whether continued participation is in his or her best interest.Reference Appelbaum3

The European Clinical Trials Directive (Directive 2001/20/E),4 as well as US consent regulations,5,6 focus on consent capacity at the time of enrolment. However, as explicitly acknowledged in section 34 of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 for England and Wales, in some longitudinal studies, a participant may lose capacity to consent prior to the conclusion of the project. Furthermore, researchers have an ethical duty to ensure that participants are giving competent voluntary consent throughout study participation.7 The Public Policy Platform from the US National Alliance on Mental Illness asserts that ‘Research participants should be carefully evaluated before and throughout the research for their capacity to comprehend information and their capacity to consent to continued participation in the research’.8 Conversely, other relevant stakeholders suggest that uniform assessment of decision-making capacity, even at the point of initial enrolment, may be unnecessary and potentially exacerbate stigma associated with mental illness.9 Guidelines regarding this matter would ideally be informed by empirical data. There is now a sizable empirical literature on informed consent among patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, but these studies have been almost exclusively focused on the time of initial study enrolment.Reference Appelbaum3,Reference Jeste, Depp and Palmer10,Reference Kaup, Dunn, Saks, Jeste and Palmer11

Among participants in the schizophrenia arm of the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials in Intervention Effectiveness study, Stroup et al Reference Stroup, Appelbaum, Gu, Hays, Swartz and Keefe12 found 24% evidenced >1 standard deviation decline and 20% a >1 standard deviation improvement on the understanding subscale of the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR)Reference Appelbaum and Grisso13 over a 6- to 18-month follow-up. Better baseline cognitive function predicted longitudinal improvement, and worsening of symptoms predicted declines in decisional capacity. These findings illustrate that fluctuating decisional capacity occurs in a non-trivial proportion of participants in psychiatric clinical trials. But the term ‘decisional capacity’ refers to a patient's potential to understand (as well as appreciate, reason with and express a choice about) the relevant information. The construct overlaps with, but is not fully synonymous with, that of a manifest level of performance on measures of decisional capacity, which is constrained by one's capacity, but also by contextual factors, including the quality of the consent process.Reference Dunn, Palmer, Karlawish, Miller and Cummings14 Capacity, as a trait, might be less malleable; manifest comprehension can be readily enhanced by optimising the consent/disclosure process.Reference Eyler and Jeste15

Cross-sectional studies demonstrate that a simple process using questions to assess understanding and then providing corrective feedback can improve participants' within-session comprehension of consent-relevant information.Reference Taub and Baker16-Reference Misra, Socherman, Park, Hauser and Ganzini19 The dearth of longitudinal studies makes it difficult to assess whether information is then effectively retained. Nonetheless, given the ease with which iterative questioning and re-explanation can be incorporated into standard consent procedures, it is worth considering if such methods lead to durable changes in manifest comprehension. In the present study of 161 patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, we examined whether within-session gains in understanding made through corrective feedback were maintained over time, as well as examining the factors associated with change in level of decisional capacity over a follow-up period of up to 24 months. We hypothesised that there would be significant retention of gains in understanding information across visits. We also examined potential predictors of within-individual changes in understanding, appreciation and reasoning over time, including diagnostic category, age, education, severity of psychopathology and cognitive functioning.

Method

Study design

This was a longitudinal within-participants comparison of decisional capacity assessed at baseline, 1 week, 3 months, 12 months and 24 months. As described below, in addition to assessing decisional capacity at these time points, severity of psychiatric symptoms and neurocognitive dysfunction were also assessed at all but the 1-week visit.

Participants

The participants in this study were 132 community-dwelling out-patients with schizophrenia and 29 with bipolar disorder considering participation in a study of the short- and long-term side-effects of antipsychotic medications among middle-aged and older patients (131 of whom enroled in the host study). Some participants provided baseline decisional capacity data for prior reports;Reference Kaup, Dunn, Saks, Jeste and Palmer11,Reference Palmer, Dunn, Depp, Eyler and Jeste18,Reference Palmer and Jeste20 however, the present report is the first investigation of the longitudinal data. We limited analyses to participants with a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.21 For inclusion in the present analyses all participants were required to have contributed decisional capacity data for at least two of the five time points; 161 participants met this criterion (20 additional patients for whom we had only baseline data were excluded from the present analyses); 137 participants completed at least three visits, 92 completed at least four visits and 52 completed all five visits. (In some instances participants missed an earlier visit but then returned for a later visit. For example, 20 missed the 1-week visit but then completed the 3-month visit.) Diagnoses were established by participants' mental healthcare providers. This protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of California, San Diego Human Research Protections Program, and all participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

The host study was a longitudinal investigation of the side-effects of Food and Drug Administration-approved antipsychotic medications among middle-aged and older patients.Reference Dolder and Jeste22 Procedures for the host study were generally non-invasive, involving clinical interviews, psychopathology ratings, brief cognitive testing and evaluations for motor side-effects (such as tardive dyskinesia) that were repeated at regular intervals for periods of up to 2-5 years. The host study was itself minimal risk in that none of the evaluations was painful or dangerous, there was no placebo control, and participants were permitted to stay on their current medications as managed by their clinical provider.

Measures

Sociodemographic information regarding each participant's age, education, gender, ethnic background and medication status was collected through interview or review of available records.

Manifest comprehension and capacity to consent to research

Manifest comprehension and capacity to consent to research was evaluated with the MacArthur Treatment Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR).Reference Appelbaum and Grisso13 This 15-20 min, semi-structured interview provides subscale scores for four dimensions of decision-making capacity: understanding (range 0-26), appreciation (range 0-6), reasoning (range 0-8) and expression of a choice (range 0-2). Higher scores indicate better performance. As per standard MacCAT-CR procedures, information relevant to answering the items was tailored to a specific protocol (the host study described above). The disclosure of study-related information was presented verbally and was embedded as part of the MacCAT-CR interview. (Formal consent for the host study, including review of the associated informed consent form, was conducted after completion of the baseline decisional capacity evaluation with those participants who expressed an interest in such participation during the MacCAT-CR interview.) As the construct of decision-making capacity refers to one's potential for comprehending disclosed information, rather than merely one's memory for information, standard MacCAT-CR procedures make provisions for correcting any initially misunderstood information. Specifically, information that is initially misunderstood is re-explained and retested. We scored the understanding subscale three times - Trial 1: reflecting the person's response after the initial disclosure; Trial 2: after re-explanation of any poorly understood information; Trial 3: after a second re-explanation of any lingering areas of suboptimal understanding. The same procedure was employed during follow-up evaluations at 1 week, 3 months, 12 months and 24 months.

Severity of psychopathology

Severity of psychopathology was measured at all the visits except the 1-week visit, with the positive, negative and general symptom subscales of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS),Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler23 and with a four-item PANSS mania factor.Reference Lindenmayer, Brown, Baker, Schuh, Shao and Tohen24 In addition, severity of depressive symptoms was evaluated with the 17-item version of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD).Reference Hamilton25

Neuropsychological functioning

Neuropsychological functioning was assessed with the following neurocognitive test battery (repeated at all but the 1-week visit): Arithmetic, Digit Span, Letter-Number Sequencing, Digit Symbol, and Symbol Search subtests from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-III),Reference Wechsler26 Trail Making Test Parts A and B,Reference Reitan and Wolfson27 Hopkins Verbal Learning Test - Revised (free recall total),Reference Brandt and Benedict28 Story Memory Test (learning),Reference Heaton, Miller, Taylor and Grant29 Brief Visuospatial Memory Test - Revised (free recall total),Reference Benedict30 Family Pictures subtest from the Wechsler Memory Scale - Third Edition (immediate recall),Reference Wechsler31 Wisconsin Card Sorting Test 64-version (conceptual level responses),Reference Kongs, Thompson, Iverson and Heaton32 Stroop Test (Interference Trial, number completed).Reference Golden and Freshwater33 At the baseline evaluation the participants completed additional neuropsychological tests that were not included in the present analyses (see Palmer & JesteReference Palmer and Jeste20); the above subset of tests was selected to focus on cognitive abilities that were thought most likely to fluctuate during the course of the study. Each test score was coded such that higher scores indicated better performance; scores were then transformed to a z-score scale using the normalised rank function in SPSS 19.0 for Windows. We then calculated a composite mean z-score at each visit, which we used as the neurocognitive variable in our statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses

Paired t-tests comparing MacCAT-CR understanding scores at Trial 3 to Trial 1, within each session, were conducted to examine the degree to which understanding of disclosed material improved with re-explanation. In addition, paired t-tests comparing the MacCAT-CR Trial 1 scores at each follow-up visit to the baseline Trial 3 scores were conducted to evaluate the degree to which the within-session gains were lost by the follow-up visit.

Hierarchical linear modelling (HLM)Reference Raudenbush and Bryk34 was used to examine the trajectory of the decisional capacity subscale scores, i.e. understanding (Trials 1 and 2), appreciation and reasoning across at least two and up to five repeated assessments. The Trial 3 scores were excluded from the HLM as they were expected to have a more constricted range than those for Trial 1 and Trial 2. (Inclusion of Trial 3 scores also would have inflated the number of parallel analyses.) Trial 2 scores correspond to ‘decisional capacity’ as operationalised under standard MacCAT-CR procedures.Reference Appelbaum and Grisso13 We examined baseline (i.e. intercept) and longitudinal (i.e. slope) performances of the MacCAT-CR subscales at both the individual participant and group levels. The hypothesis that people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder would show stable performance on all components of the MacCAT-CR was evaluated in terms of the slope of the unconditional growth model, because this parameter reflects the increase, decrease or stable pattern of scores across time of the entire sample. We conducted follow-up examinations of predictors when the variances around the intercept and slope were significant. Model testing proceeded in three phases: (a) unconditional model (to calculate intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs)), (b) unconditional growth model with time (in weeks) as a predictor and (c) conditional growth models (intercepts and slopes as outcomes model) with both baseline (diagnostic category, age and education level) and longitudinal (HRSD, PANSS subscale scores and neurocognitive composite z-score) predictors. (The HRSD, PANSS and neurocognitive tests were not administered at the 1-week visit.) All regression coefficients presented in the results section are unstandardised b. Significance was P<0.05 (two-tailed) for all analyses.

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample

Relative to the participants with schizophrenia, those with bipolar disorder were slightly older (mean age 52.5 years (s.d. = 6.9) and 55.7 (s.d. = 10.7), respectively, t(159) = 2.04, P = 0.043), and were more educated (mean years completed 12.3 (s.d. = 2.2) and 13.4 (s.d. = 2.1) respectively, t(159) = 2.32, P = 0.022). There were no other significant group differences in sociodemographic or clinical characteristics (Table 1). (This was an out-patient/community-dwelling sample, and participants were generally clinically stable at the times of assessment.)

Persistence or dissipation over study visits of within-session gains in understanding from repeated explanation

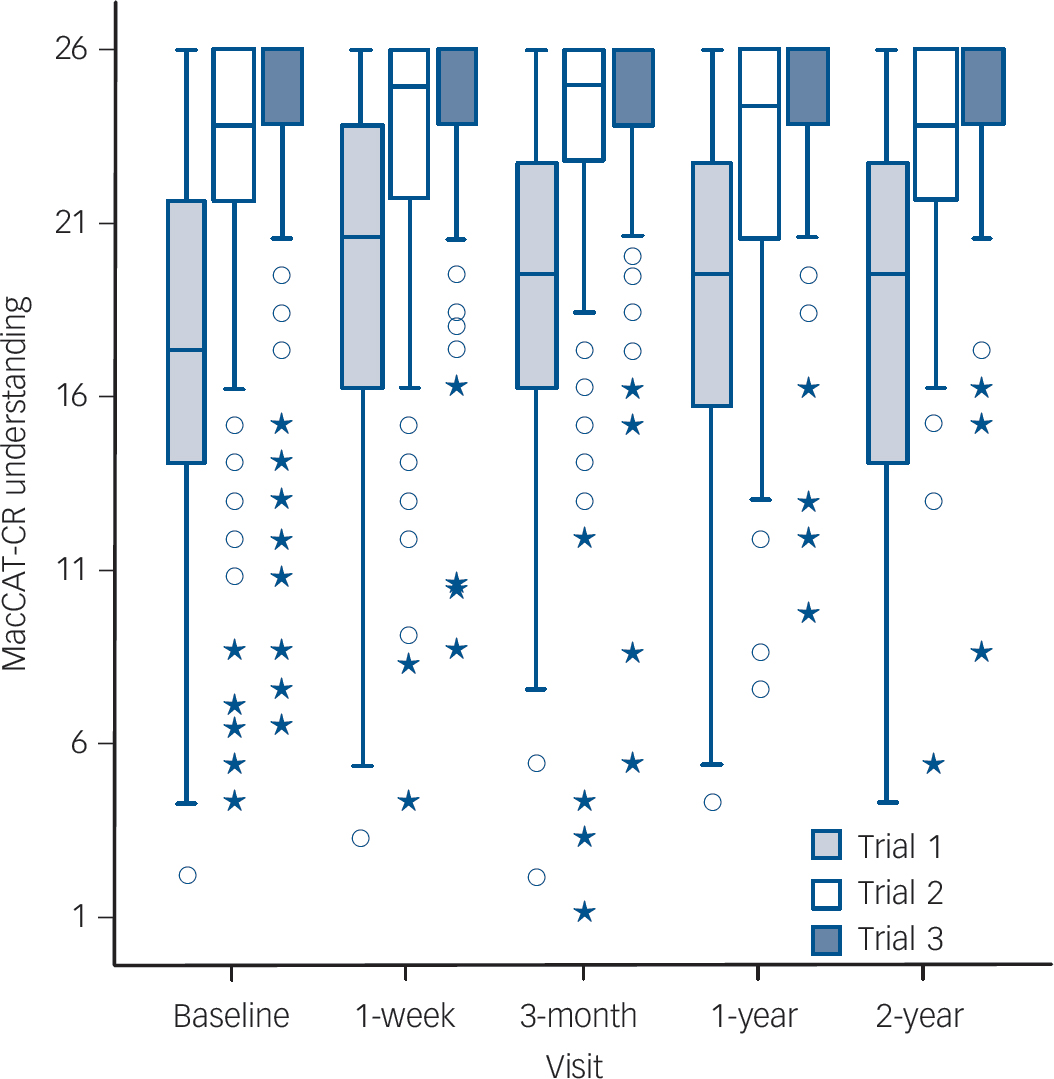

The distribution of the understanding scores across trials at each study visit is depicted in Fig. 1. The overall pattern was one of within-session improvement when initially misunderstood information was re-explained, but with a dissipation of improvement ('re-spreading' of scores) at each subsequent follow-up assessment. At the baseline visit the mean understanding score at Trial 3 was 6.5 (s.d. = 4.0) points higher than the Trial 1 score (17.3 (s.d. = 5.5) v. 23.8 (s.d. = 4.0) respectively, t(159) = 20.7, P<0.001). The parallel within-session gain from Trial 1 to Trial 3 was similar at each subsequent visit (online Table DS1). Comparing Trial 1 scores at each follow-up to the baseline Trial 3 scores provides an index of the degree to which within-visit gains were subsequently lost between visits. The mean Trial 1 score at the 1-week follow-up was 4.4 points lower than the mean baseline Trial 3 score, t(139) = 12.7, P<0.001. Similarly, the Trial 1 scores at the 3-month, 12-month, and 24-month follow-ups were 4.8, 5.1, and 4.9 points below the baseline Trial 3 score respectively (all three ts >7.80, all three P-values <0.001).

Table 1 Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

| Schizophrenia group (n = 132) | Bipolar disorder group (n = 29) | t or χ2 | d.f. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 52.5 (6.9) | 55.7 (10.4) | 2.04 | 159 | 0.043 |

| Education, years: mean (s.d.) | 12.3 (2.2) | 13.4 (2.1) | 2.32 | 159 | 0.022 |

| Gender, women: n (%) | 55 (41.7) | 14 (48.2) | 0.42 | 1 | 0.515 |

| Ethnicity, White: n (%) | 76 (57.6) | 21 (72.4) | 2.19 | 1 | 0.139 |

| Depression (17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, total) mean (s.d.) | 8.9 (6.1) | 10.7 (5.3) | 1.48 | 155 | 0.141 |

| Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), mean (s.d.) | |||||

| Positive symptoms (PANSS positive total) | 14.4 (6.3) | 12.8 (4.8) | 1.26 | 158 | 0.211 |

| Negative symptom score (PANSS negative total) | 13.2 (5.0) | 13.4 (4.9) | 0.17 | 158 | 0.867 |

| General psychopathology (PANSS general, total) | 27.1 (7.3) | 28.0 (7.2) | 0.65 | 158 | 0.519 |

| Mania (PANSS mania index) | 5.6 (2.4) | 5.8 (2.2) | 0.33 | 158 | 0.740 |

| Composite neuropsychological z-score, mean (s.d.) | –0.05 (.70) | –0.05 (.64) | 0.017 | 153 | 0.987 |

Stability and trajectory of scores

Between-individual variance, reflected by the ICCs from the unconditional model of the understanding Trials 1 and 2, appreciation and reasoning components was 0.59, 0.43, 0.41 and 0.16, respectively. Time (in weeks) was positively and significantly related to performance on understanding Trials 1 and 2 and reasoning, i.e. scores on these components appeared to get better over time (understanding Trial 1 b = 0.013, s.e. = 0.01, P = 0.016; understanding Trial 2 b = 0.010, s.e. = 0.00, P = 0.028; reasoning b = 0.010, s.e. = 0.00, P<0.001). These improvements over time were of very modest magnitude, translating into a 1.32 increase in the understanding Trial 1 score over 2 years and a 1.04 increase in both understanding Trial 2 and reasoning scores. Time was not significantly related to appreciation (b = 0.00, s.e. = 0.00, P = 0.315).

Of the baseline predictors, age and education were not significant for any of the MacCAT-CR scores (online Table DS2). Diagnostic status was a significant predictor of appreciation (b = 0.45, P = 0.010) and reasoning (b = 0.40, P = 0.022) over time. The regression coefficients related to neuropsychological ability were positive and significant predictors of performance on all four components of the MacCAT-CR (understanding Trial 1 b = 3.61, Trial 2 b = 2.45; appreciation b = 0.43; reasoning b = 0.34; all four P-values <0.001). That is, better neuropsychological performance was associated with better scores on the MacCAT-CR regardless of time point. Negative symptom scores were negatively and significantly associated with the understanding Trial 1 performance over time (b = −0.15, P = 0.030), so that worse negative symptoms (higher scores) were predictive of poorer performance. Negative symptoms were not significantly predictive of the other components of the MacCAT-CR (online Table DS2). Positive symptoms were not predictive of any MacCAT-CR components (online Table DS2), but general psychopathology and depression were both significantly related to appreciation (b = −0.04 and 0.04, respectively, P-values <0.044).

Fig. 1 Box-and-whisker plots depicting distribution of scores on the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR) understanding subscale (Trials 1, 2 and 3) at each study visit.

Upper and lower boundaries of each box represent the third and first quartiles (Q3 and Q1, respectively), the median (Q2) is indicated with a horizontal bar in the box. Interquartile range (IQR) is Q3-Q1. The fences of the boxes represent the Q3 + (1.5×IQR) and Q1–(1.5×IQR). There were no outliers beyond the upper fence. Circles represent mild outliers, i.e. values beyond the lower fence [Q1–(1.5×IQR)] but not beyond Q1–(3×IQR). Asterisks indicate extreme outliers, i.e. values beyond Q1–(3×IQR).

Discussion

Main findings

This is the first large-scale study to examine the degree to which within-session gains in comprehension achieved with corrective feedback during consent for a psychiatric research trial are maintained over time. The overall observed pattern was one of within-session improvement of comprehension, but with a dissipation of improvement at each subsequent follow-up assessment. This dissipation does not appear to be a change in decisional capacity per se as the overall pattern of scores between study visits for was one of general stability.

Current regulations regarding the research consent process are focused on the time of initial enrolment.4-6 But the present findings illustrate the importance of incorporating an interactive informed consent discussion into every study visit. This recommendation need not entail a formal reiteration of the printed consent form. (As noted in a report from the Institute of Medicine, printed consent forms seem to have been ‘hijacked’ as a method of managing institutional risk, rather than as a means for optimising communication of key information to research participants.Reference Federman, Hannam and Lyman Rodriguez35) But brief, simple language disclosures, provided in a systematic format with a natural comprehensible conversational tone, along with brief evaluation of participants' comprehension, can be readily incorporated with minimal added burden (see Palmer et al Reference Palmer, Cassidy, Dunn, Spira and Sheikh17). This might be as simple as, at the beginning of each study visit, ensuring that the participant understands the purpose and procedures of that particular study visit in the context of the larger study goals, as well as any adverse or unpleasant side-effects that might occur. But the amount of detail reviewed, and the degree to which such procedures are themselves standardised and become a focus of formal institutional review board oversight, should depend on factors such as the vulnerability of the study population to cognitive impairment, as well as the risks associated with study participation.

The current findings indicate an overall pattern of stability in decisional capacity over time. There were slight improvements in MacCAT-CR performance over study visits, but the magnitude of these practice effects was relatively small. However, there was also significant between-individual heterogeneity in the slopes of decisional capacity scores over time, suggesting there may be a subset of patients for whom fluctuation in consent-related skills may indeed be a relevant concern. Neuropsychological performance was associated with better scores on the MacCAT-CR regardless of time point. When dealing with patients whose cognitive abilities may change, clinical trials researchers should be alert to possible changes in the participant's ability to give meaningful ongoing consent for participation.

Limitations

Schizophrenia diagnosis (rather than bipolar disorder) appeared to be associated with greater fluctuation in some aspects of manifest performance or decisional capacity; however, interpretation of the latter finding is limited given the relatively euthymic level of affective symptoms in our sample. That is, among people with severe acute manic symptoms, and/or severe depressive symptoms, greater fluctuation than presently observed might reasonably be expected in both manifest performance and in decisional capacity (see Misra et al Reference Misra, Rosenstein, Socherman and Ganzini36). Furthermore, in the context of consent for a procedurally complex trial, or one with a complex risk-benefit profile, retention of information and/or overall stability of decisional capacity may be different from the pattern observed in the present study. Such distinctions may be of particular importance when the issue is not just whether the level of manifest comprehension has changed, but whether some threshold for capable/incapable status has been crossed (see Stroup et al Reference Stroup, Appelbaum, Gu, Hays, Swartz and Keefe12). With regard to the need to avoid singling out or unduly stigmatising those with severe mental illness, it should also be noted that our sample was restricted to patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. It is quite possible that the pattern of dissipation in understanding seen between study visits would be present in non-psychiatric research participants as well.

Implications

The above limitations notwithstanding, the present findings have two important implications for how informed consent is conducted in the context of longitudinal research: (a) informed consent discussions need to be interactive and integrated throughout the clinical trial process, not merely at the time of enrolment, and (b) some, but not all, patients experience fluctuations in decisional capacity. If a participant is at risk for not being able to monitor and evaluate whether continued participation remains in his/her best interest, for example because of an exacerbation of cognitive dysfunction, then periodic reassessment of that decisional capacity may be warranted. (There were also some isolated findings with regard to severity of symptoms and decisional capacity, but those for neurocognitive performance were stronger and more consistent at least within this relatively stable community-dwelling sample.) When a participant loses capacity for consent, this need not entail automatic withdrawal from the study. Some jurisdictions allow research to continue with assent from the participant and consent from a legally authorised representative. Indeed, even if a participant loses capacity for consent to research, he or she may still retain capacity to appoint a proxy for decision-making.Reference Kim, Karlawish, Kim, Wall, Bozoki and Appelbaum37 Another possible approach is the use of a research advance directive in which participants are asked to indicate their preferences, a priori, in the event they lose capacity to consent.Reference Stocking, Hougham, Danner, Patterson, Whitehouse and Sachs38 The specific solution will, of course, depend on the provisions recognised in the applicable legal jurisdiction but knowing the factors associated with fluctuating capacity to consent can be helpful in making appropriate contingency plans.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by NIH grants MH64722, T32MH019934, 5P30MH066248, and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.