Emotional distress and depressive symptoms are common in the community. Reference Singleton, Bumpstead, O'Brien, Lee and Meltzer1 Although there is increasing consensus on the management of major depression, 2 there remains a need to develop treatments that meet the full range of peoples' needs and preferences. In particular, there is a lack of clarity regarding the optimal management of individuals with subthreshold levels of depressive symptoms and emotional distress. Reference Middleton, Shaw, Hull and Feder3,Reference Pincus, Davis and McQueen4 It has been suggested that a significant proportion of people present with distress because of social, physical and economic problems, and that they may benefit from social interventions that do not medicalise their difficulties. Reference Middleton and Shaw5 There is a significant literature suggesting that social support affects the onset, course and outcome of depression, Reference Middleton, Shaw, Hull and Feder3,Reference Brown and Harris6 and individuals with distress appreciate emotional and social support. Reference Lester, Freemantle, Wilson, Sorohan, England and Griffin7 One way of providing social support is through befriending, defined as ‘a relationship between two or more individuals which is initiated, supported and monitored by an agency that has defined one or more parties as likely to benefit. Ideally the relationship is non-judgemental, mutual, and purposeful, and there is a commitment over time’. Reference Dean and Goodlad8 A recent survey found over 500 charitable and voluntary sector organisations offering befriending in the UK. Reference Dean and Goodlad8 Clinical guidelines suggest a role for befriending for people with chronic depression, 2 although the evidence was limited. We therefore conducted a systematic review to examine the clinical and cost-effectiveness of befriending for individuals in the community, with a focus on the impact on depressive symptoms and emotional distress.

Method

Inclusion criteria

Design

The review included randomised controlled trials only.

Participants

Individuals aged 14 or over, residing in the community and allocated to a befriending intervention, irrespective of ethnicity, gender, nationality or health status. Individuals did not need to be recruited on the basis of diagnosed depression or a specific level of baseline distress, although data were extracted on this issue.

Intervention

Befriending was defined as an intervention that introduces the client to one or more individuals whose main aim is to provide the client with additional social support through the development of an affirming, emotion-focused relationship over time. The relationship should be established and monitored via an agency that has identified one or more parties as likely to benefit. Reference Dean and Goodlad8 The social support offered should primarily be non-directive and emotional in nature. Studies were excluded where informational, instrumental or appraisal support Reference Langford, Bowsher, Maloney and Lillis9,Reference Faulkner and Davies10 formed a key component of the intervention. Also excluded were: mentoring interventions (which focus more on goal-setting and less on the development of a social relationship), self-help, psychoeducational interventions and formal psychological therapy such as counselling or cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT).

Befriending could be delivered by volunteers or paid workers, but had to be offered as a free service. Only befriending interventions delivered on an individual basis (either in person or via the telephone or internet) were included. ‘Befrienders’ could be untrained lay persons or professionals qualified in relationship-based interventions. Where the befriender was a trained professional, great attention was paid to ensure the befriending actions were focused on developing a non-directive, emotion-focused relationship. Studies where the ‘befriender’ was a member of the client's existing social or care provider network (e.g. family member, caseworker, general practitioner) were excluded.

Comparison

Three types of comparison were included: comparisons with usual care or no treatment controls, with alternative active comparators (including medication or other psychological intervention) or other comparisons (e.g. between different types of befriending).

Outcomes

A range of psychological and social well-being outcomes were considered relevant to befriending, but to allow comparison across interventions, the primary outcome was depressive symptoms (the most commonly reported outcome and best overall measure of emotional distress), with perceived social support as a secondary outcome.

Search strategy

To identify both published trials and studies in progress, multiple bibliographic databases and research registers were searched: MEDLINE; EMBASE; PsycINFO; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); CINAHL (nursing); Campbell Collaboration Register (SPECTR-C2 and SRPOC); Web of Knowledge; National Research Register; PsiTri (Register of Clinical Trials in Mental Health); International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Registry; Meta Trials Register; and Department of Health Research Findings Register (REFER). Electronic searches were supplemented with manual scanning of the reference lists of retrieved articles and known reviews of social support interventions. The flow of studies is illustrated in online Fig. DS1. Specific search strategies were developed for each database, using a combination of text terms and subject headings where applicable (see example MEDLINE search in online Appendix DS1). Searches were conducted in July–August 2007 and updated in April 2008. Studies dating from 1980 were included, with no restrictions on language of publication.

Method of the review

One reviewer (N.M.) screened titles and abstracts to determine potential inclusion, with a 10% random sample of records independently screened by a second reviewer (H.L.) to check reliability. Inclusion was subsequently confirmed by a team of four reviewers (N.M., H.L., L.G. and C.C.G.) who worked in pairs, independently checking the full text of all retrieved articles. Uncertainties and disagreements were resolved through team discussion and/or contact with study authors. Data were extracted from each included study by a pair of reviewers working independently using a pro forma. This covered details of the client population and the nature of the befriending intervention. Data on methodological quality were also extracted, and included concealment of allocation, masking, sample size and power calculations, uptake and attrition rates, and statistical analyses. Although multiple assessments of methodological quality were made, for the meta-analysis, an overall rating of methodological quality was used based on two procedures designed to preserve group comparability: concealment of allocation, i.e. ensuring that those responsible for judgements of eligibility are unaware of the next allocation in the sequence, to protect against selection bias; Reference Higgins and Green11 and loss to follow-up. Study quality was rated ‘high’ if allocation was adequately concealed and at least 80% follow-up reported, ‘medium’ if one of these criteria was met, and ‘low’ if neither was met. Data relevant to external validity were also extracted, including the context of recruitment, methods of recruitment and proportion of eligible clients included in the trial.

Analysis

Outcome data were extracted by two reviewers (N.M. and P.B.) working independently. Analyses were divided into short term (less than 12 months post-randomisation) and long term (12 months or more). Reported measures included a mix of dichotomous and continuous outcomes. We translated continuous measures to a standardised effect size (i.e. mean of intervention group minus mean of control group, divided by the pooled standard deviation). We translated outcomes reported as dichotomous variables to standardised effect sizes using the logit transformation. Reference Lipsey and Wilson12 Negative effects sizes represent interventions that were more effective (i.e. reduced depression symptoms by more than the control).

Analyses were conducted in Comprehensive Meta Analysis (version 2.0) and Stata (Version 9.2), both on Windows. Heterogeneity was measured using the I 2 statistic, which estimates the percentage of total variation across studies that can be attributed to heterogeneity rather than chance. Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman13 As a result of the varied nature of the interventions, the analyses reported here used random effects models.

Possible publication bias was investigated graphically by plotting effect size against standard error, and statistically by Egger's regression method. Reference Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider and Minder14,Reference Sterne, Egger and Davey Smith15

Results

Searches generated 10 538 records, from which 24 studies were identified as meeting all inclusion criteria. Reference Barnett and Parker16–Reference Wiggins, Oakley, Roberts, Turner, Rajan and Austerberry43 Online Table DS1 lists these studies and the comparisons they included, whereas online Appendix DS2 lists excluded studies.

Of the 24 included studies, 17 reported comparisons between befriending and usual care or ‘no treatment’ controls, 10 compared befriending with alternative psychological treatments, and 4 reported other comparisons (online Table DS1). The limited data concerning other comparisons are not reported here.

Description of populations and interventions

All studies used individual randomisation. Sample sizes ranged from 32 to 509 with a mean of 171. Nine studies reported adequate concealment of allocation and 17 reported >80% follow-up. Eight studies were rated high quality, ten medium and six low (online Table DS2).

Befriending was used in a range of populations including family carers (four studies), pregnant (two) and postnatal women (three), people with schizophrenia (two), depression (four), multiple sclerosis (one), chronic illness (one), prostate cancer (two), and older individuals with ‘low support’ (four) or who were recently bereaved (one). Five studies (21%) specifically recruited individuals with depression, but there were also significant rates of depressive symptoms in studies recruiting on the basis of other characteristics (online Table DS3).

Befrienders included social workers (1 study), therapists (3), nurses (3), health visitors (1), midwives (1), research/secretarial staff (2), students (2) and lay volunteers (12). Befriending involved a variable number of contacts and duration (from three contacts in 7 days, to monthly contacts for 1 year), with median figures of weekly contacts of 1 hour's duration delivered for approximately 3 months. Most befriending was delivered face to face or in combination with telephone contact (16 studies), but eight studies delivered the intervention entirely via telephone. Befrienders were matched with clients in eight studies (online Table DS4). Further details of the populations, interventions, study quality and outcomes can be found in online Tables DS2–5.

Clinical effectiveness

Befriending v. usual care or no treatment

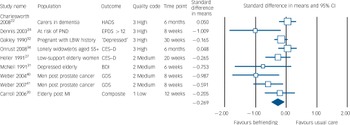

Nine comparisons of befriending and usual care or no treatment included a measure of depression as a short-term outcome (median 12 weeks) and provided suitable data for meta-analysis. Befriending demonstrated a standardised mean difference (SMD) of −0.27 (95% CI −0.48 to −0.06, I 2 = 56%, Fig. 1). Four of these nine short-term studies were high quality. There was evidence of funnel plot asymmetry in the short-term outcomes (online Fig. DS2).

Fig. 1 Short-term effects of befriending v. usual care on depression outcomes.

HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PND, postnatal depression; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; LBW, low birth weight; CES–D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale, MI, myocardial infarction.

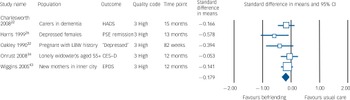

Five studies reported depression outcomes over the long term (median 13 months) and demonstrated an SMD of −0.18 (95% CI −0.32 to −0.05, I 2 = 7.8%, Fig. 2). All five long-term studies were high quality.

Fig. 2 Long-term effects of befriending v. usual care on depression outcomes.

HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PSE, Present State Exam; LBW, low birth weight; CES–D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

Six comparisons included a measure of social support as outcome, and four provided suitable data for meta-analysis of outcomes in the short term (median 27 weeks), demonstrating an SMD of 0.004 (95% CI −0.14 to 0.15, I 2 = 0%).

Befriending v. active treatments

Ten comparisons of befriending with another active intervention included a measure of depression as outcome, but only five had sufficient data for calculation of effect sizes. Data from comparisons of different active treatments were not pooled.

Befriending was less effective than CBT both in adolescents with depression (SMD = 0.41, 95% CI −0.07 to 0.89) Reference Brent, Holder, Kolko, Birmaher, Baugher and Roth18 and in medication-resistant individuals with schizophrenia (SMD = 0.23, 95% CI −0.18 to 0.65), Reference Sensky, Turkington, Kingdon, Scott, Scott and Siddle39 and was less effective than nurse cognitive–behavioural problem-solving in carers of people with dementia (SMD = 0.45, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.94). Reference Chang21 Befriending did not differ markedly from a nurse education and self-efficacy intervention in older adults recovering from myocardial infarction (SMD = 0.10, 95% CI −0.37 to 0.57), Reference Carroll and Rankin20 or from contact with local community support groups for new mothers in deprived innercity circumstances (SMD = −0.05, 95% CI −0.27 to 0.18), Reference Wiggins, Oakley, Roberts, Turner, Rajan and Austerberry42,Reference Wiggins, Oakley, Roberts, Turner, Rajan and Austerberry43 or from systemic family therapy in adolescents with depression (SMD = 0.07, 95% CI −0.43 to 0.57). Reference Brent, Holder, Kolko, Birmaher, Baugher and Roth18

Cost-effectiveness

Three economic analyses were reported (online Tables DS2 and DS5), although only two combined cost and effectiveness data. Reference Charlesworth, Shepstone, Wilson, Thalanany, Mugford and Poland22,Reference Charlesworth, Shepstone, Wilson, Reynolds, Mugford and Price23,Reference Onrust, Smit, Willemse, van den Bout and Cuijpers34,Reference Wiggins, Oakley, Roberts, Turner, Rajan and Austerberry42,Reference Wiggins, Oakley, Roberts, Turner, Rajan and Austerberry43 None of the studies that included economic outcomes reported significant clinical benefits from befriending (Figs 1 and 2). Only one study suggested that befriending had a reasonable chance of being cost-effective using conventional levels of willingness to pay for a quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). Reference Onrust, Smit, Willemse, van den Bout and Cuijpers34

Discussion

Limitations

Befriending is a complex intervention that is difficult to define, and there are inevitable issues concerning the scope of the review and the types of interventions that are included and excluded. Decisions about inclusion of individual studies are complex and we therefore contacted study authors directly on a number of occasions to ensure that, despite variation in the populations, the core content of all interventions reflected non-directive emotional support. This reflected our interest in a relatively simple intervention based on emotional support that could be delivered by peers with relatively limited training. We therefore excluded interventions such as non-directive counselling (which is based on emotional support but is a more complex intervention requiring training and supervision), mentoring (which is primarily goal-rather than relationship-focused, and is specifically distinguished from befriending by several national befriending and volunteering organisations) and self-help groups (which have a different ethos, and involve additional effects of group dynamics).

The populations included in the review were very varied because the need for befriending is often based on identified deficiencies in social support among vulnerable groups (e.g. caregivers, recently bereaved spouses) rather than the presence of depression symptoms per se. Nevertheless, many of the included individuals had significant levels of psychological symptoms (online Table DS3).

There is legitimate disagreement in the literature as to the level of heterogeneity that can reasonably be justified in a meta-analysis. There may be concerns that it is problematic to combine befriending interventions across such diverse populations as carers of people with dementia, adolescents and pregnant women. However, the types of fine-grained distinctions that a mental health researcher or clinician might make between different befriending interventions may not be made by other decision-makers such as service managers or policy makers, who may view the provision of low-level emotional support as a generic intervention. The benefits of pooling are increasingly recognised. Reference Ioannidis, Patsopoulos and Rothstein44 It should also be noted that there was only a moderate degree of heterogeneity present in the short-term outcomes. This suggests that the distress experienced by many individuals in a variety of populations is amenable to intervention, even if such distress is not necessarily appropriate for conventional psychiatric or psychotherapeutic intervention.

The analyses did suggest the possibility of publication bias. Depression was used as the primary outcome for this analysis because it was the most commonly reported outcome and best overall measure of distress, but this may not be the most appropriate outcome for befriending interventions. Evidence relating to cost-effectiveness was reported in only three studies.

Interpretation of the findings

On the basis of the current findings, would mental health services, particularly those in primary care settings, be justified in adding a befriending option for people with depressive symptoms and distress? Is this a service that practice-based commissioners should perhaps be considering as one part of the overall mental healthcare system? After all, depression and emotional distress are common and costly. The World Health Organization multi-country survey of 2000–2001 found that major depression affects around 5% of women and 3% of men per year. Around three times as many people have symptom levels below the cut-off for major depression which, although relatively mild, are still associated with significant distress and impairment of social functioning. Reference Rapaport, Judd, Schettler, Yonkers, Thase and Kupfer45 Cross-sectional surveys have shown an increasing prevalence, prompting talk of an ‘epidemic of depression’. Reference Compton, Conway, Stinson and Grant46 Depression is a leading cause of long-term sickness absence in the UK, Reference Henderson, Glozier and Holland-Elliott47 and all high-income countries have seen year-on-year increases in antidepressant prescribing in primary care since selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were introduced in 1990. Reference Middleton, Gunnell, Whitely, Dorling and Frankel48

Currently, the effectiveness evidence for befriending does not meet National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence depression guidelines for adoption (i.e. an SMD of 0.5 or more). Reference Wiggins, Oakley, Roberts, Turner, Rajan and Austerberry42 However, it should be noted that studies conducted in primary care often report lower effect sizes than those in specialist settings or with volunteer populations, Reference Raine, Haines, Sensky, Hutchings, Larkin and Black49,Reference Churchill, Hunot, Corney, Knapp, McGuire and Tylee50 and the effect sizes of befriending in the short and longer-term are not substantively different to those associated with conventional treatments in primary care such as collaborative care Reference Gilbody, Bower, Fletcher, Richards and Sutton51 and counselling. Reference Bower, Rowland and Hardy52 Lower effect sizes in primary care and community settings may reflect differences in study quality in different settings, or the capacity of different patient populations to benefit from active intervention, related to the natural history of distress and potentially high levels of ‘spontaneous remission’ in non-specialist settings.

Provision of emotional support through befriending in the National Health Service (NHS) could therefore have many advantages for individuals, mental health services and the wider health economy. It could, for example, extend patient choice within the lower levels of the recommended ‘stepped care’ model for depression Reference Bower and Gilbody53 and provide a less medicalised approach to emotional distress. Reference Middleton, Shaw, Hull and Feder3 It could offer a preventive strategy for individuals at risk of developing mental health problems, in line with the major UK policy focus on health prevention throughout the NHS. 54 Less costly and onerous staff training requirements could improve both implementation and access to treatment, especially if combined with a telephone-based system such as those being developed in other mental health services. Reference Richards and Suckling55 Low cost might make such an intervention more feasible in low-income countries and those where the proportion of health budget spending on mental health is relatively small. 56 The limited evidence on the value of peer befriending also offers the prospect of addressing aspects of the complex social inclusion agenda through employing ex-service users as befrienders, building on the example of the role of ‘support, time and recovery workers’ for whom lived experience of mental illness is a key requirement. 57

Although the evidence base comparing befriending with other psychological interventions suggests it is less effective than CBT, it should be noted that these trials all used befriending as a comparator designed to control for ‘common factors’ (i.e. time, attention, warmth). The delivery of befriending in these studies may therefore have been suboptimal – what has been described as an ‘intent to fail’ comparator. Reference Westen and Morrison58 Further primary research on the effectiveness of befriending v. established treatments such as CBT is now required. Patient preference designs may also be useful in this context. Reference Torgerson and Sibbald59

One hypothesis underpinning work in this field is that providing supportive interventions like befriending will increase individuals' perceived social support, in turn bolstering their coping responses to stress, so preventing or reducing depressive symptoms. Reference Brand, Lakey and Berman60 However, the meta-analyses presented here suggest that befriending has an effect on depressive symptoms but not on perceived social support. This could reflect the fact that fewer studies reported social support outcomes or that social support is more difficult to measure. However, this highlights the need for further in-depth research to elucidate the mechanisms by which befriending works, the populations in which it is most effective and optimal methods of delivery. Reference Campbell, Fitzpatrick, Haines, Kinmonth, Sandercock and Spiegelhalter61,Reference Campbell, Murray, Darbyshire, Emery, Farmer and Griffiths62

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ros McNally for undertaking bibliographic database searches, and Annette Barber for assistance with retrieving articles for the review. This article presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.