Depressive disorders are the second most important cause of disability in developed countries (Reference Murray and LopezMurray & Lopez, 1997) but a substantial minority of depressed patients fail to respond to antidepressant treatment (Reference Anderson, Nutt and DeakinAnderson et al, 2000). Although newer antidepressants have tolerability and safety benefits over older tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), similar efficacy generally is reported (Reference EdwardsEdwards, 1992; Reference Gross and HuberGross & Huber, 1999; Reference AndersonAnderson, 2000; Reference Geddes, Freemantle and MasonGeddes et al, 2001). It is potentially of great clinical importance if an antidepressant were to be more effective than comparators, and understanding why may shed light on how antidepressants work. It has been proposed (Reference Nelson, Mazure and BowersNelson et al, 1991; Reference Seth, Jennings and BindmanSeth et al, 1992; Reference Heninger, Delgado and CharneyHeninger et al, 1996) that antidepressants with a dual action of inhibiting the reuptake of both noradrenalin and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) may be more effective than drugs acting on a single monoamine (e.g. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SSRIs). Venlafaxine is the first drug to be marketed that inhibits both noradrenalin and 5-HT reuptake without actions at other receptors (Reference Holliday and BenfieldHolliday & Benfield, 1995). We present a systematic review investigating the relative efficacy and tolerability of venlafaxine compared with other antidepressants.

METHOD

Relevant trials were identified from our existing database (Reference Eccles, Freemantle and MasonEccles et al, 2000) and from systematic searches of electronic databases. The search terms were VENLAFAXINE, EFEXOR or EFFEXOR. Databases searched included Medline, Embase, Biosis, PsychLit, National Research Register, Healthstar, SIGLE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, DARE, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register and Current Controlled Trials. A total of 2349 trials were identified from our electronic search strategy. We carried out a manual search of reference lists of included studies and requested unpublished data from authors and study sponsors.

Inclusion criteria

Trials were included if they were double-blind, randomised studies comparing venlafaxine with an alternative antidepressant for the treatment of depression. The definition of depression was intentionally broad and included explicit clinical or research criteria for major depression (such as DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) or if the clinician considered the patient to be depressed and eligible for antidepressant treatment. Two of the researchers (D. S. and C. D.) made an independent assessment of each potentially eligible study and disagreements were resolved through discussion within the team.

Data abstraction

Design characteristics and quality assessment

We abstracted data on the inclusion and exclusion criteria for each study, the dose and regimen of venlafaxine and alternative antidepressants, the adequacy of randomisation and concealment of allocation (as reported in the paper), number of patients randomised, loss to follow-up, form of analysis (completer analysis or last observation carried forward), relevant clinical outcomes reported, age and gender of participants and length of follow-up. When specific variables were not reported within a given trial, the authors of the paper were contacted to obtain the missing data. If this was unsuccessful, we contacted the sponsors. Data were abstracted on all available patients randomised in the trials and patients were analysed on the basis of initial random allocation to treatment group (intention to treat) whenever possible.

Clinical outcomes

The primary outcome was the mean depression severity measure assessed by the final (end of trial) Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Reference HamiltonHamilton, 1960), the Montgomery and Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (Reference Montgomery and ÅsbergMontgomery & Åsberg, 1979) or the Clinical Global Impression (Reference GuyGuy, 1976), with preference given in that order if more than one scale was reported. Secondary outcome variables were response rate (typically 50% or greater drop in depression rating scale from baseline) and remission rate (depression rating scale below a certain score, e.g. HRSD <8). Data on tolerability were abstracted by collecting ‘all cause’ withdrawals from each treatment group and also the attributed reason for withdrawal from therapy (lack of efficacy and adverse effects).

Statistical analysis

The primary efficacy outcome was the pooled standardised difference in mean treatment effect. For this measure, standardised effect sizes (difference in final rating scale means divided by the within-study standard deviation) were estimated from the efficacy data for each treatment group. Where an estimate of study variance was not available, this was imputed by taking the average for the studies using the same outcome measure. Secondary binary outcomes of response and remission, as well as tolerability data, were calculated as the odds ratio and absolute risk difference.

A simulation method was used to estimate pooled treatment effects using Gibbs sampling in BUGS software (Reference Smith, Spiegelhalter and ThomasSmithet al, 1995; Reference Freemantle, Cleland and YoungFreemantle et al, 1999). This method is analogous to standard methods but does not require large sample assumptions, making it superior in meta-analysis where these assumptions frequently are not met. It has the additional advantage that the predictive value of different factors, such as patient severity or dose, may be examined using meta-regression approaches (Reference Freemantle, Cleland and YoungFreemantle et al, 1999). Absolute risk differences were calculated using standard methods (Reference DerSimonian and LairdDerSimonian & Laird, 1986) and interpreted as ‘number needed to treat’ (NNT). Negative NNTs are often described as ‘number needed to harm’.

Fixed effects approaches to meta-analysis assume that each trial contributes an estimate of a constant population effect for a treatment, whereas random effects approaches assume that there is no single population effect but a distribution (range) of effects. Random effects models were used where venlafaxine was compared with a variety of agents (e.g. in comparison with SSRIs) but fixed effects models were used where venlafaxine was compared with individual agents.

Meta-regression was used to examine the predictive value of potentially important explanatory factors on the primary efficacy outcome measure (Reference Freemantle, Cleland and YoungFreemantle et al, 1999). This hierarchical approach to data modelling enables examination of the effect of trial characteristics while preserving the structure of individual trials. The factors that we identified a priori were: size of trial; in-patient v. out-patient status; design criteria (last observation carried forward v. completer analysis). The analysis on size of trial is a particularly helpful method of identifying potential publication bias and is analogous to using a funnel plot. Other factors also investigated were age and gender, comparator drug class, length of follow-up, rating scale used (e.g. HRSD or Montgomery and Å sberg Depression Rating Scale), dose of venlafaxine and if the variance was imputed.

RESULTS

Included trials

A total of 32 studies met the inclusion criteria (Table 1), with comparisons of venlafaxine with TCAs (clomipramine, imipramine, dothiepin (dosulepin) and amitriptyline), SSRIs (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine and sertraline) and other drugs (trazodone and mirtazapine). There were 5562 patients in totalFootnote 1 : 3844 in the twenty trials comparing venlafaxine with SSRIs (SSRI n=1857); 1356 in the nine trials comparing venlafaxine with TCAs (TCA n=579); and 418 in the three trials comparing venlafaxine with other drugs (othern=212). The average trial size was 179 patients (range 28-382). The average length of follow-up was 10 weeks (range 4-48). Most trials used the last observation carried forward for the primary analysis (see Table 1). For three of the trials, we imputed the measure of variance because the data were not available and could not be obtained from the authors or sponsors. None of the trials indicated whether concealment of allocation was conducted appropriately.

Table 1 Description of included trials1

| Drug class | Comparator | Trial | Citation | No. of studies | No. of patients | Venlafaxine dose | Mean age | Female (%) | Method | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCA | 9 | 1508 | 1315 | 50 | 685 | |||||

| Amitriptyline | Gentil et al, 2000 | 23 | 1 | 116 | 103 | 39 | 81 | LOCF | Out-patient | |

| Clomipramine | Smeraldi et al, 1998 | 24 | 2 | 113 | 83 | 72 | 73 | LOCF | Out-patient | |

| Samuelian & Hackett, 1998 | 25 | 102 | 105 | 47 | 62 | LOCF | Out-patient | |||

| Dothiepin (dosulepin) | Mahapatra & Hackett, 1997 | 26 | 2 | 92 | 100 | 74 | 70 | LOCF | Out-patient | |

| Stanley et al, 1998 | 14 | 86 | 75 | NA | NA | Completers | Out-patient | |||

| Imipramine | Shrivastava et al, 1994 | 27 | 4 | 381 | 165 | 43 | 54 | LOCF | Out-patient | |

| Benkert et al, 1996 | 28 | 167 | 233 | 47 | 68 | LOCF | In-patient | |||

| Lecrubier et al, 1997 | 29 | 153 | 111 | 40 | 69 | LOCF | Out-patient | |||

| Schweizer et al, 1994 | 30 | 146 | 182 | 42 | 66 | LOCF | Out-patient | |||

| SSRI | 20 | 3989 | 1505 | 47 | 675 | |||||

| Fluoxetine | Costa & Silva, 1998 | 31 | 13 | 382 | 91 | 40 | 79 | LOCF | Out-patient | |

| Tylee et al, 1997 | 15 | 341 | 75 | 45 | 71 | Completers | Out-patient | |||

| Dierick et al, 1996 | 32 | 314 | 111 | 44 | 65 | LOCF | Out-patient | |||

| Rudolph et al, 1998 | 33 | 308 | 300 | Not clear | Out-patient | |||||

| Silverstone & Ravindran, 1999 | 34 | 249 | 141 | 42 | 60 | Completers | Out-patient | |||

| Schatzberg & Cantillon, 2000 | 35 | 204 | 150 | 71 | 50 | LOCF | Out-patient | |||

| Rudolph & Feiger, 1999 | 36 | 203 | 175 | 40 | 70 | LOCF | Out-patient | |||

| Unpublished data2 | 37 | 196 | 150 | NA | NA | LOCF | Out-patient | |||

| Unpublished data3 | 38 | 156 | 150 | NA | NA | LOCF | Out-patient | |||

| Geerts et al, 1999 | 39 | 146 | 102 | 43 | 68 | LOCF | Out-patient | |||

| Tzanakaki et al, 2000 | 40 | 109 | 225 | 48 | 79 | LOCF | In-patient | |||

| Alves et al, 1999 | 41 | 87 | 113 | NA | NA | LOCF | Out-patient | |||

| Clerc et al, 1994 | 42 | 68 | 200 | 51 | 68 | LOCF | In-patient | |||

| Fluvoxamine | Unpublished data4 | 43 | 2 | 92 | 150 | NA | NA | LOCF | Out-patient | |

| Zanardi et al, 2000 | 44 | 28 | 225 | 51 | 64 | LOCF | In-patient | |||

| Paroxetine | McPartlin et al, 1998 | 45 | 4 | 361 | 75 | 45 | 68 | LOCF | Out-patient | |

| Salinas, 1997 | 46 | 246 | 113 | 47 | 63 | LOCF | Out-patient | |||

| Poirier & Boyer, 1999 | 47 | 123 | 269 | 43 | 72 | LOCF | Out-patient | |||

| Ballus et al, 2000 | 48 | 84 | 113 | NA | NA | LOCF | Out-patient | |||

| Sertraline | Mehtonen et al, 2000 | 49 | 1 | 147 | 114 | 43 | 66 | LOCF | Out-patient | |

| Other | 3 | 418 | 1665 | 53 | 645 | |||||

| Mirtazapine | Guelfi, 1999 | 50 | 1 | 157 | 255 | 45 | 64 | LOCF | In-patient | |

| Trazodone | Cunningham et al, 1994 | 51 | 2 | 149 | 160 | 41 | 55 | LOCF | Out-patient | |

| Trazodone | Smeraldi et al, 1998 | 24 | 112 | 83 | 72 | 72 | LOCF | Out-patient | ||

| Total | 32 | 5562 | 1475 | 48 | 675 |

Primary outcome

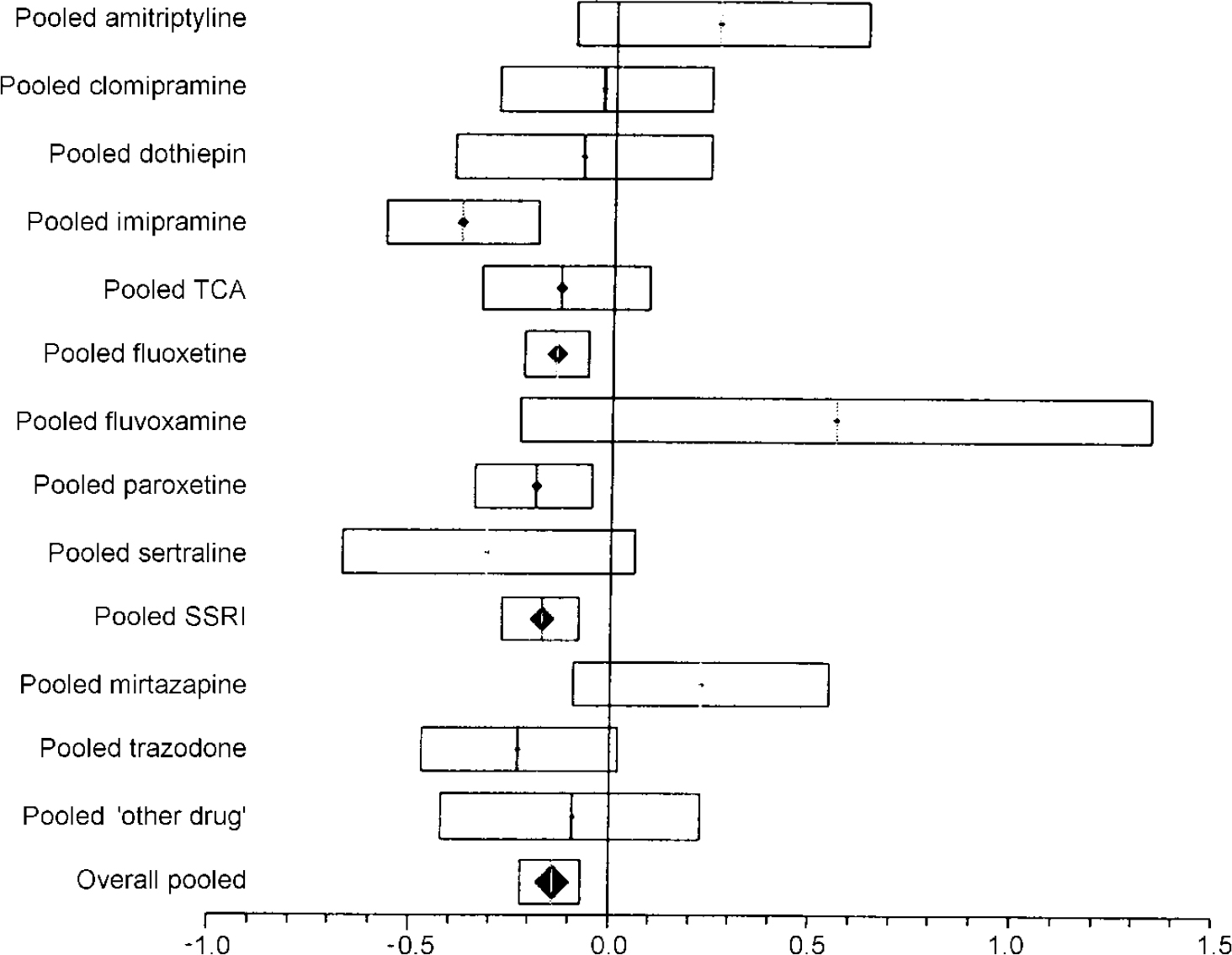

There were 29 comparisons in the effect size analysis of clinical efficacy (Table 2). The overall effect size estimate was −0.14 (95% CI −0.22 to −0.07) in favour of venlafaxine. The size of effect (given a pooled standard deviation of 8.3) is equivalent to the final HRSD score, being about 1.2 points lower on venlafaxine. For the SSRIs, the effect size estimate was −0.17 (95% CI −0.27 to −0.08). Effect sizes for the TCAs and the ‘other drug’ categories were similar but not significantly different from venlafaxine (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Plot of pooled efficacy of venlafaxine compared with other antidepressants. The bars show the effect size (difference in final rating scale score divided by pooled final standard deviation) and the 95% CI. Results falling to the left of the line of no effect (zero) indicate an advantage to venlafaxine.

Table 2 Effect size analysis

| Class | Comparator | Effect size | 95% CI | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCA | Amitriptyline | 0.26 | -0.10 to 0.63 | Gentil et al, 2000 |

| Pooled amitriptyline | 0.26 | -0.10 to 0.63 | ||

| Clomipramine | 0.05 | -0.32 to 0.42 | Smeraldi et al, 1998 | |

| Clomipramine | -0.11 | -0.51 to 0.28 | Samuelian & Hackett, 1998 | |

| Pooled clomipramine | -0.03 | -0.29 to 0.24 | ||

| Dothiepin | -0.02 | -0.44 to 0.4 | Mahapatra & Hackett, 1997 | |

| Dothiepin | -0.18 | -0.71 to 0.36 | Stanley et al, 1998 | |

| Pooled dothiepin | -0.08 | -0.40 to 0.24 | ||

| Imipramine | -0.4 | -0.64 to −0.16 | Shrivastava et al, 1994 | |

| Imipramine | -0.32 | -0.65 to 0.02 | Schweizer et al, 1994 | |

| Pooled imipramine | -0.38 | -0.57 to −0.19 | ||

| Pooled TCA | -0.13 | -0.33 to 0.09 | ||

| SSRI | Fluoxetine | -0.02 | -0.22 to 0.19 | Costa & Silva, 1998 |

| Fluoxetine | 0.18 | -0.07 to 0.43 | Tylee et al, 1997 | |

| Fluoxetine | -0.18 | -0.40 to 0.04 | Dierick et al, 1996 | |

| Fluoxetine | -0.14 | -0.37 to 0.09 | Rudolph et al, 1998 | |

| Fluoxetine | -0.12 | -0.37 to 0.14 | Silverstone & Ravindran, 1999 | |

| Fluoxetine | -0.48 | -0.76 to −0.2 | Schatzberg & Cantillon, 2000 | |

| Fluoxetine | -0.21 | -0.49 to 0.07 | Rudolph & Feiger, 1999 | |

| Fluoxetine | -0.22 | -0.50 to 0.06 | Unpublished data1 | |

| Fluoxetine | 0.02 | -0.30 to 0.35 | Unpublished data2 | |

| Fluoxetine | -0.5 | -0.85 to −0.15 | Geerts et al, 1999 | |

| Fluoxetine | -0.08 | -0.46 to 0.3 | Tzanakaki et al, 2000 | |

| Fluoxetine | -0.34 | -0.77 to 0.1 | Alves et al, 1999 | |

| Fluoxetine | -0.58 | -1.06 to −0.09 | Clerc et al, 1994 | |

| Pooled fluoxetine | -0.14 | -0.22 to −0.06 | ||

| Fluvoxamine | 0.56 | -0.23 to 1.34 | Zanardi et al, 2000 | |

| Pooled fluvoxamine | 0.56 | -0.23 to 1.34 | ||

| Paroxetine | -0.1 | -0.31 to 0.12 | McPartlin et al, 1998 | |

| Paroxetine | -0.46 | -0.73 to −0.19 | Salinas, 1997 | |

| Paroxetine | -0.07 | -0.42 to 0.29 | Poirier & Boyer, 1999 | |

| Paroxetine | -0.07 | -0.50 to 0.37 | Ballus et al, 2000 | |

| Pooled paroxetine | -0.19 | -0.34 to −0.05 | ||

| Sertraline | -0.31 | -0.67 to 0.06 | Mehtonen et al, 2000 | |

| Pooled sertraline | -0.31 | -0.67 to 0.06 | ||

| Pooled SSRI | -0.17 | -0.27 to −0.08 | ||

| Other | Mirtazapine | 0.23 | 0.55 to −0.09 | Guelfi, 1999 |

| Pooled mirtazapine | 0.23 | 0.55 to −0.09 | ||

| Trazodone | -0.11 | -0.44 to 0.23 | Cunningham et al, 1994 | |

| Trazodone | -0.37 | -0.74 to 0.01 | Smeraldi et al, 1998 | |

| Pooled trazodone | -0.23 | -0.47 to 0.02 | ||

| Pooled ‘other drug’ | -0.09 | -0.42 to 0.23 | ||

| Overall pooled | -0.14 | -0.22 to −0.07 |

The results appeared consistent across the SSRIs but there were differences between the TCA studies, notably imipramine: the effect size was −0.38 (95% CI −0.57 to −0.19), favouring venlafaxine, whereas there was no benefit in studies against other TCAs (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Response rates

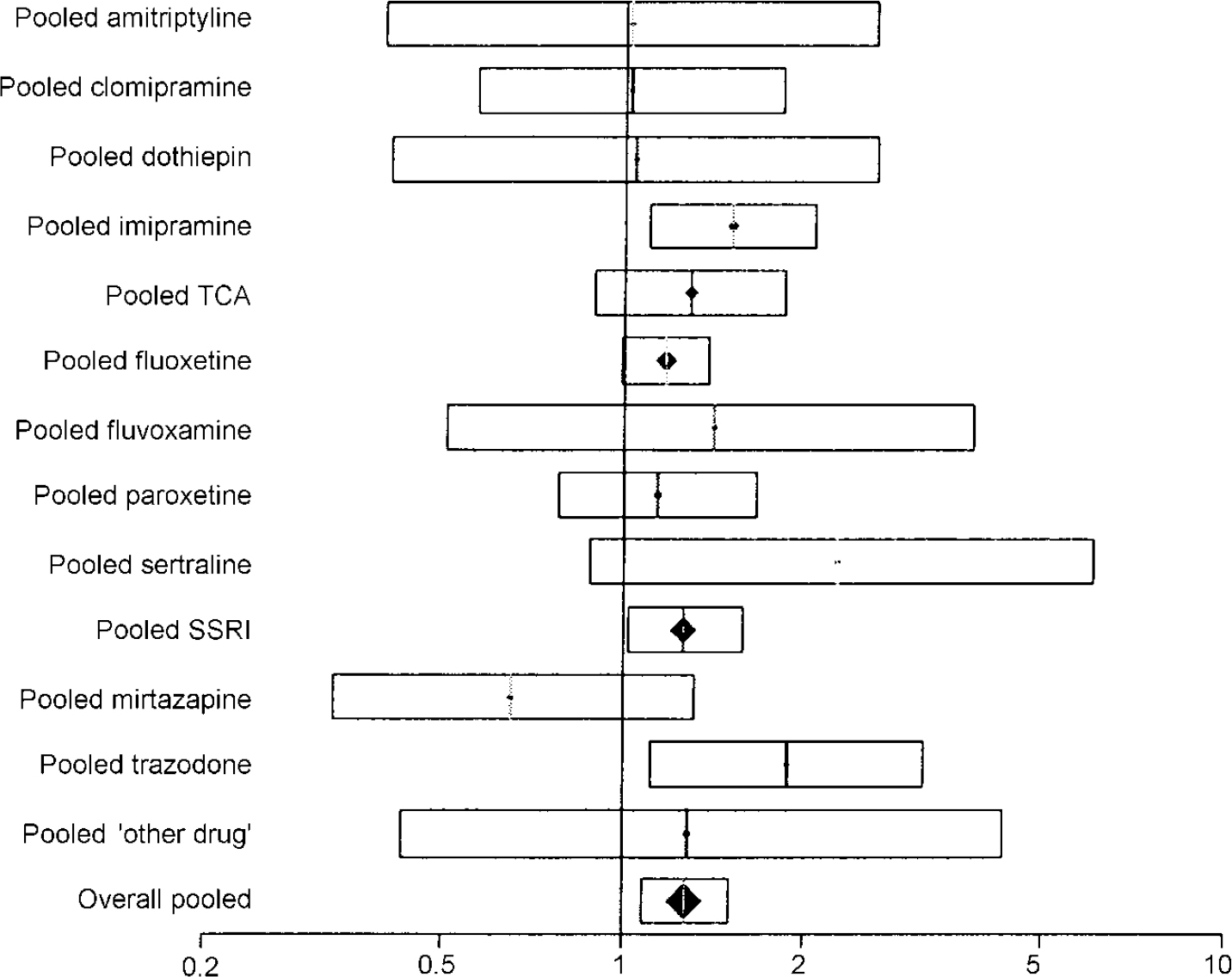

Table 3 shows the estimated response rates. The overall odds ratio for response was 1.27 (95% CI 1.07-1.52). The risk difference was 0.05 (95% CI 0.02-0.09), with an NNT of 19 (95% CI 11-63). The pooled results for different drug classes were similar to this overall effect (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Plot of pooled response rate to venlafaxine compared with other antidepressants. The bars show the odds ratio and the 95% CI. Results falling to the right of the line of no effect (I) indicate an advantage to venlafaxine.

Table 3 Response analysis

| Class | Comparator | Odds ratio | 95% Cl | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCA | Amitriptyline | 1.02 | 0.4-2.62 | Gentil et al, 2000 |

| Pooled amitriptyline | 1.02 | 0.4-2.62 | ||

| Clomipramine | 0.54 | 0.21-1.36 | Smeraldi et al, 1998 | |

| Clomipramine | 1.92 | 0.8-4.64 | Samuelian & Hackett, 1998 | |

| Pooled clomipramine | 1.02 | 0.57-1.83 | ||

| Dothiepin | 1.04 | 0.41-2.63 | Mahapatra & Hackett, 1997 | |

| Pooled dothiepin | 1.04 | 0.41-2.63 | ||

| Imipramine | 1.72 | 1.04-2.87 | Shrivastava et al, 1994 | |

| Imipramine | 0.76 | 0.39-1.47 | Benkert et al, 1996 | |

| Imipramine | 2.55 | 1.1-6.14 | Lecrubier et al, 1997 | |

| Imipramine | 2.18 | 0.79-6.14 | Schweizer et al, 1994 | |

| Pooled imipramine | 1.51 | 1.10-2.07 | ||

| Pooled TCA | 1.29 | 0.89-1.85 | ||

| SSRI | Fluoxetine | 0.99 | 0.55-1.78 | Costa & Silva, 1998 |

| Fluoxetine | 0.82 | 0.47-1.43 | Tylee et al, 1997 | |

| Fluoxetine | 0.54 | 0.33-0.87 | Dierick et al, 1996 | |

| Fluoxetine | 1.59 | 0.96-2.61 | Rudolph et al, 1998 | |

| Fluoxetine | 1.29 | 0.74-2.27 | Silverstone & Ravindran, 1999 | |

| Fluoxetine | 1.42 | 0.79-2.56 | Schatzberg & Cantillon, 2000 | |

| Fluoxetine | 1.32 | 0.73-2.39 | Rudolph & Feiger, 1999 | |

| Fluoxetine | 0.97 | 0.47-1.97 | Unpublished data1 | |

| Fluoxetine | 2.63 | 1.2-5.82 | Geerts et al, 1999 | |

| Fluoxetine | 1.44 | 0.6-3.5 | Tzanakaki et al, 2000 | |

| Fluoxetine | 2.26 | 0.64-9.05 | Alves et al, 1999 | |

| Fluoxetine | 2.67 | 0.86-8.45 | Clerc et al, 1994 | |

| Pooled fluoxetine | 1.17 | 0.99-1.38 | ||

| Fluvoxamine | 1.41 | 0.51-3.82 | Unpublished data2 | |

| Pooled fluvoxamine | 1.41 | 0.51-3.82 | ||

| Paroxetine | 1.01 | 0.58-1.75 | McPartlin et al, 1998 | |

| Paroxetine | 1.49 | 0.68-3.29 | Poirier & Boyer, 1999 | |

| Paroxetine | 1.15 | 0.43-3.07 | Ballus et al, 2000 | |

| Pooled paroxetine | 1.14 | 0.78-1.67 | ||

| Sertraline | 2.27 | 0.88-6.08 | Mehtonen et al, 2000 | |

| Pooled sertraline | 2.27 | 0.88-6.08 | ||

| Pooled SSRI | 1.26 | 1.02-1.58 | ||

| Other | Mirtazapine | 0.65 | 0.33-1.31 | Guelfi, 1999 |

| Pooled mirtazapine | 0.65 | 0.33-1.31 | ||

| Trazodone | 1.7 | 0.78-3.75 | Cunningham et al, 1994 | |

| Trazodone | 2.06 | 0.89-4.78 | Smeraldi et al, 1998 | |

| Pooled trazodone | 1.88 | 1.11-3.17 | ||

| Pooled ‘other drug’ | 1.28 | 0.43-4.31 | ||

| Overall pooled | 1.27 | 1.07-1.52 |

Remission rates

Table 4 and Fig. 3 display the pooled remission results. The overall odds ratio for remission rate was 1.36 (95% CI 1.14-1.61), favouring venlafaxine. The overall risk difference was 0.07 (95% CI 0.03-0.11), giving an NNT of 14 (95% CI 9-29).

Fig. 3 Plot of pooled remission rate on venlafaxine compared with other antidepressants. The bars show the odds ratio and the 95% CI. Results falling to the right of the line of no effect (I) indicate an advantage to venlafaxine.

Table 4 Remission analysis

| Class | Comparator | Odds ratio | 95% Cl | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCA | Amitriptyline | 1.03 | 0.46-2.32 | Gentil et al, 2000 |

| Pooled amitriptyline | 1.03 | 0.46-2.32 | ||

| Pooled TCA | 1.03 | 0.46-2.32 | ||

| SSRI | Fluoxetine | 1.15 | 0.52-2.57 | Costa & Silva, 1998 |

| Fluoxetine | 1.06 | 0.61-1.85 | Tylee et al, 1997 | |

| Fluoxetine | 1.49 | 0.9-2.47 | Rudolph et al, 1998 | |

| Fluoxetine | 1.02 | 0.6-1.75 | Silverstone & Ravindran, 1999 | |

| Fluoxetine | 1.8 | 0.97-3.35 | Schatzberg & Cantillon, 2000 | |

| Fluoxetine | 2.03 | 1.04-3.99 | Rudolph & Feiger, 1999 | |

| Fluoxetine | 1.43 | 0.59-3.51 | Unpublished data1 | |

| Fluoxetine | 2.17 | 1.02-4.62 | Geerts et al, 1999 | |

| Fluoxetine | 1.23 | 0.52-2.89 | Tzanakaki et al, 2000 | |

| Fluoxetine | 1.5 | 0.57-3.92 | Alves et al, 1999 | |

| Pooled fluoxetine | 1.42 | 1.17-1.73 | ||

| Fluvoxamine | 0.36 | 0.05-2.44 | Zanardi et al, | |

| Pooled fluvoxamine | 0.36 | 0.05-2.44 | ||

| Paroxetine | 1.09 | 0.69-1.71 | McPartlin et al, 1998 | |

| Paroxetine | 1.59 | 0.89-2.82 | Salinas, 1997 | |

| Paroxetine | 2.68 | 1.08-6.87 | Poirier & Boyer, 1999 | |

| Paroxetine | 1.47 | 0.57-3.85 | Ballus et al, 2000 | |

| Pooled paroxetine | 1.4 | 1.05-1.88 | ||

| Sertraline | 2.57 | 1.15-5.82 | Mehtonen et al, 2000 | |

| Pooled sertraline | 2.57 | 1.15-5.82 | ||

| Pooled SSRI | 1.43 | 1.21-1.71 | ||

| Other | Mirtazapine | 0.69 | 0.33-1.43 | Guelfi, 1999 |

| Pooled mirtazapine | 0.69 | 0.33-1.43 | ||

| Pooled ‘other drug’ | 0.69 | 0.33-1.43 | ||

| Overall pooled | 1.36 | 1.14-1.61 |

Remission rates were measured in only 18 of the trials and, of these, 16 used an SSRI agent as the comparator. The result for the pooled SSRI comparison was similar to the overall effect.

None of the factors that were hypothesised to influence the estimate of primary outcome were significantly predictive of greater efficacy in meta-regression analyses (analysis not shown).

Meta-regression analysis and visual inspection of funnel plots provided no evidence of publication bias, although did not exclude the possibility of the existence of such bias.

Treatment discontinuation

Table 5 shows an analysis of drop-outs by reason and comparator drug class. The overall risk difference of −0.004 (95% CI −0.029 to 0.020) indicates that there are 0.4% fewer drop-outs overall in the venlafaxine group, and the difference is not statistically or clinically significant. The only statistically significant drop-out comparison exists for drop-outs due to side-effects compared with the ‘other drug’ category, where there is a risk difference of 0.221 (95% CI 0.065-0.376), giving an NNT of 5 (95% CI 3-15) in favour of other drugs. However, because the overall difference in drop-out is equivalent, this result is countered by drop-out for all other causes.

Table 5 Drop-out analysis by cause and drug class

| Risk difference (venlafaxine minus comparator) | Lower CL | Upper CL | NNT1 | Lower CL | Upper CL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All causes | ||||||

| All drugs | -0.004 | -0.029 | 0.020 | -224 | -34 | 49 |

| SSRI | 0.002 | -0.025 | 0.029 | 494 | -40 | 34 |

| TCA | -0.028 | -0.089 | 0.033 | -36 | -11 | 30 |

| Other drug | -0.080 | -0.196 | 0.035 | -12 | -5 | 28 |

| Unsatisfactory response | ||||||

| All drugs | -0.006 | -0.016 | 0.004 | -159 | -62 | 275 |

| SSRI | -0.008 | -0.019 | 0.003 | -123 | -52 | 350 |

| TCA | 0.003 | -0.020 | 0.026 | 341 | -50 | 39 |

| Other drug | -0.032 | -0.123 | 0.059 | -31 | -8 | 17 |

| Side-effects | ||||||

| All drugs | 0.010 | -0.007 | 0.026 | 105 | -141 | 38 |

| SSRI | 0.017 | -0.006 | 0.040 | 60 | -161 | 25 |

| TCA | -0.025 | -0.070 | 0.020 | -40 | -14 | 51 |

| Other drug | 0.221 | 0.065 | 0.376 | 5 | 15 | 3 |

DISCUSSION

Efficacy

This meta-analysis provides evidence that in the treatment of depressive disorders all antidepressants are not equal. Pooling data from all currently available studies reveals that venlafaxine carries an advantage of about 1.2 HRSD points over other antidepressants. The majority of comparisons were with SSRIs, where the effect appeared consistent across the different drugs. In contrast, it is less clear that the advantage is consistent across other antidepressants such as TCAs, where imipramine is the only individual drug that clearly demonstrates lesser efficacy. This does not, however, reduce the importance of the findings for the primary outcome measure — venlafaxinev. any other antidepressent in reducing symptoms of depression — in which a clear advantage was identified.

The results are of probable clinical significance, with an NNT of 19 (95% CI 11-63) for response and 14 (95% CI 9-29) for remission. The two data-sets do not include all of the same studies and are not as comprehensive as the data used in primary analysis of effect sizes, so the absolute figures must be viewed as approximate. However, this magnitude of advantage for venlafaxine over other antidepressants is potentially of considerable importance, given the often prolonged or even chronic nature of depressive episodes. It is increasingly recognised that improvement of depression on antidepressants is often incomplete or partial so that remission rates are relatively low (Reference FerrierFerrier, 1999) and only 42% of patients in the studies that we included achieved remission by the end of the study. Patients who fail to reach remission have significantly greater continuing morbidity and higher relapse rates than those who do experience remission (Reference Cornwall and ScottCornwall & Scott, 1997). If only one extra person reaches remission when treated with venlafaxine instead of an SSRI for every 14 patients treated, then this is a potentially important health benefit. It suggests that even if not used first line, venlafaxine should be considered for patients having an inadequate response to other antidepressants.

Our study confirms the more limited meta-analysis recently reported by Thase et al (Reference Thase, Entsuah and Rudolph2001), which only included a small subset (eight) of studies against SSRIs and therefore cannot be considered systematic. It only assessed efficacy using remission rates with an odds ratio of 1.5 (95% CI 1.3-1.9) in favour of venlafaxine. The NNT was not calculated formally but appears to be about 10 from the difference in remission rates (45% v. 35%); this is a greater advantage to venlafaxine than we found with a larger data-set.

Our analysis of the tolerability of venlafaxine as measured by total treatment drop-outs and those due to side-effects did not suggest that greater efficacy was offset by poorer tolerability overall or against SSRIs or TCAs. More patients dropped out of treatment owing to side-effects on venlafaxine than trazodone or mirtazapine, suggesting poorer tolerability than these drugs, but the small number of studies makes it difficult to draw conclusions.

Mechanism underlying venlafaxine's greater efficacy

We have reported previously being unable to identify a relationship between pharmacology and efficacy using a meta-regression analysis of a variety of antidepressants compared with SSRIs (Reference Freemantle, Anderson and YoungFreemantle et al, 2000). There were, however, considerable problems in that analysis, relating to being able to identify accurately the acute pharmacology of many antidepressants in vivo. In this study some of these problems are overcome through using a single agent and it appears that the most plausible mechanism by which venlafaxine may exert increased efficacy in comparison with SSRIs is its ability to inhibit not only 5-HT reuptake but also the reuptake of noradrenalin (Reference Holliday and BenfieldHolliday & Benfield, 1995). Whether this is the mechanism in the case of venlafaxine has yet to be confirmed, however. The profile of its binding to human monoamine transporters suggests a weak affinity for the noradrenalin transporter compared with the 5-HT transporter (Reference Owens, Morgan and PlottOwens et al, 1997; Reference Tatsumi, Groshan and BlakelyTatsumi et al, 1997). At lower doses, venlafaxine appears to act as an SSRI and it is unclear at what dose significant noradrenalin effects occur. Preliminary evidence suggests that, at least outside the brain, this is somewhere between 75 and 225 mg, with one study suggesting that it may occur by 150 mg (Reference Abdelmawla, Langley and SzabadiAbdelmawla et al, 1999). It is of interest that previous meta-analyses have suggested superior efficacy for amitriptyline against other antidepressants, particularly SSRIs (Reference AndersonAnderson, 2000; Reference Barbui and HotopfBarbui & Hotopf, 2001), which adds some support to dual action conferring greater efficacy than occurs when blocking the reuptake of a single transmitter.

We did not find an effect of dose on the size of the advantage to venlafaxine over SSRIs, raising some question as to the mechanism underlying its greater efficacy. However, the studies in this meta-analysis were not designed to detect dose—response effects, most employing flexible dosing. The lack of an association between efficacy and a venlafaxine dose below or above 150 mg is probably against a strong linear dose—response over the range used but cannot rule out a non-linear relationship. Two fixed-dose studies of venlafaxine against placebo have suggested a dose—response over the range 60-225 mg (Reference KelseyKelsey, 1996; Reference Rudolph, Fabre and FeighnerRudolph et al, 1998), but the differentiation between doses has not been statistically significant and the dose at which any possible greater efficacy may arise is not clear.

Methodological considerations

The major methodological challenge to all systematic overviews is publication bias — the selective availability of trials with positive results. The comprehensive search strategies used to identify trials, the systematic attempts to identify unpublished trials and unpublished data and examination of the distribution of the results from included trials all mediate against the importance of this threat to the validity of the results of this overview. However, it has to be acknowledged that the majority of studies were sponsored by the company that markets venlafaxine and sponsorship has been suggested as a potential factor influencing the outcome of the trials (Reference Stewart and ParmarStewart & Parmar, 1996; Reference Freemantle, Anderson and YoungFreemantle et al, 2000).

Although over 5000 patients were included in the trials identified for this meta-analysis, this number is small against other clinical areas where this number of patients commonly may be included in a single trial. Further randomised trials, including those of a naturalistic design, involving larger numbers of patients in different clinical settings (particularly primary care, where the majority of treatment for major depressive disorder is conducted) are required to find out how generalisable this result is to different settings and whether venlafaxine has increased effectiveness in usual clinical practice.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

• The findings from this systematic review and meta-analysis provide some confidence that venlafaxine is more effective than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) with comparable tolerability.

-

• The size of this advantage is of probable clinical importance when the prolonged or chronic nature of depression is taken into account.

-

• Venlafaxine should be considered for patients in whom efficacy needs to be maximised and in those failing to respond to an SSRI.

LIMITATIONS

-

• Apart from the comparison with fluoxetine, there are insufficient comparisons between venlafaxine and individual SSRIs and other antidepressants to draw strong conclusions with regard to specific comparisons.

-

• Meta-analysis is dependent on the quality of individual studies included in the analysis.

-

• Drop-outs are a relatively crude proxy for tolerability.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.