Up to 90% of persons with dementia experience behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) at some point during the course of the disease. Reference Lyketsos, Lopez, Jones, Fitzpatrick, Breitner and DeKosky1,Reference Steinberg, Shao, Zandi, Lyketsos, Welsh-Bohmer and Norton2 BPSD include symptoms such as apathy, depression, anxiety, agitation, aggression, delusions, hallucinations, sleep disturbances, euphoria and disinhibition. Antipsychotics are frequently used to treat BPSD among persons with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, especially in institutional settings. Reference Laitinen, Bell, Lavikainen, Lönnroos, Sulkava and Hartikainen3–Reference Rattinger, Burcu, Dutcher, Chhabra, Rosenberg and Simoni-Wastila5 However, antipsychotic use has been associated with mortality Reference Schneider, Dagerman and Insel6–Reference Kales, Kim, Zivin, Valenstein, Seyfried and Chiang8 and serious adverse drug events including extrapyramidal symptoms, Reference Rochon, Stukel, Sykora, Gill, Garfinkel and Anderson9 hip fracture Reference Jalbert, Eaton, Miller and Lapane10 and stroke Reference Gill, Rochon, Herrmann, Lee, Sykora and Gunraj11,Reference Wu, Wang, Gau, Tsai and Cheng12 among older people with dementia. In addition, antipsychotics may accelerate cognitive decline. Reference Livingston, Walker, Katona and Cooper13–Reference Rosenberg, Mielke, Han, Leoutsakos, Lyketsos and Rabins15 According to systematic reviews and meta-analyses certain antipsychotic drugs have efficacy for specific BPSD including psychosis and aggression. Reference Lonergan, Luxenberg and Colford16–Reference Maher, Maglione, Bagley, Suttorp, Hu and Ewing19 However, improvements on rating scales for BPSD have been modest and not all randomised controlled trials have been able to demonstrate beneficial effects. As the risks of antipsychotics may outweigh their benefits among persons with Alzheimer's disease, guidelines recommend that antipsychotics should be used only in the treatment of severe psychotic symptoms, aggression and agitation when the symptoms cause significant distress or risk of harm to the patient or others. Reference Rabins, Blacker, Rovner, Rummans and Schneider20–22 There are no previous studies on when antipsychotics are prescribed for the first time in the course of Alzheimer's disease. We describe the incidence of antipsychotic use up to 8 years before and 4 years after diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease among community-dwelling persons.

Method

This study is based on a nationwide register-based cohort study MEDALZ-2005 (Medication and Alzheimer's disease) described in detail elsewhere. Reference Laitinen, Bell, Lavikainen, Lönnroos, Sulkava and Hartikainen3,Reference Tolppanen, Taipale, Koponen, Lavikainen, Tanskanen and Tiihonen23 Briefly, the MEDALZ-2005 included all community-dwelling persons diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease residing in Finland on 31 December 2005 (n = 28 093) and one age-, gender- and region of residence-matched person without Alzheimer's disease. Clinically verified Alzheimer's disease diagnoses were identified from the Special Reimbursement Register maintained by the Social Insurance Institution of Finland (SII). This register contains records of persons who are entitled for higher reimbursement due to chronic diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, diabetes and epilepsy. To be entitled for reimbursement, a patient must meet predefined criteria and a diagnosis statement must be submitted to the SII for approval. The SII requires that the medical statement verifies that the patient has: (a) symptoms consistent with Alzheimer's disease; (b) experienced a decrease in social capacity over a period of at least 3 months; (c) received a computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging scan; (d) had possible alternative diagnoses excluded and (e) received confirmation of the diagnosis by a registered geriatrician or neurologist. The SII reviews all medical statements and checks that the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease is based on the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association Reference McKhann, Drachman, Folstein, Katzman, Price and Stadlan24 and DSM-IV 25 criteria for Alzheimer's disease. This study was restricted to those persons diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in 2005 (n = 7217) and their matched control persons. Data linkage was performed by the SII and they de-identified the data. According to Finnish legislation, no ethics committee approval was required because only de-identified register-based data were used and the study participants were not contacted.

Data on all antipsychotics dispensed between 1995 and 2009 were extracted from the Finnish National Prescription Register for each study participant with and without Alzheimer's disease. The Prescription Register contains records of all reimbursed drug purchases of Finnish residents living in non-institutional settings. All drugs in the Prescription Register are categorised according to the World Health Organization (WHO) Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification system. 26 The rate of new antipsychotic users (ATC code N05A, excluding lithium and prochlorperazine) per 100 person-years was calculated for every 6 months up to 8 years before and 4 years after Alzheimer's disease diagnosis. A 2-year washout period was applied starting 10 years before Alzheimer's disease diagnosis. A new user was defined as a person who had no antipsychotic purchases during the washout period but had at least 1 antipsychotic purchase during the 12-year follow-up. The index date for the matched control person without Alzheimer's disease was defined as the date of Alzheimer's disease diagnosis of the person with Alzheimer's disease.

Data on history of schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (ICD-10 27 codes F20–29; ICD-9 28 codes 295, 297, 298, 3010 and 3012; ICD-8 29 codes 295, 297, 298, 29999, 30100 and 30120) and bipolar disorder (ICD-10 codes F30-31; ICD-9 codes 2962, 2963, 2964 and 2967; ICD-8 codes 29610, 29620, 29630, 29688 and 29699) were collected from the Hospital Discharge Register (data available since 1972). Only diagnoses recorded before diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease or index date for the controls were included as history of schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders or bipolar disorder. Persons with history of schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders or bipolar disorder were excluded with their matched pairs (n = 298) to remove the effect of these diagnoses on antipsychotic initiation.

A modified Charlson comorbidity index score Reference Charlson, Pompei, Ales and MacKenzie30 was calculated for each person at the time of Alzheimer's disease diagnosis/index date and for each antipsychotic initiator at the time of first purchase. Comorbidity score was calculated using the following diseases with corresponding scores. Score of 1: coronary artery disease, heart failure, type 1 or 2 diabetes, chronic asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, rheumatoid arthritis and disseminated connective tissue diseases. Score of 2: severe renal failure and all cancers. Data on comorbidities were extracted from the Special Reimbursement Register. Use of antidepressants (N06A) and use of benzodiazepines (N05BA, N05CD) and related drugs (N05CF) were assessed at the time of Alzheimer's disease diagnosis/index date (when comparing persons with and without Alzheimer's disease) and for each antipsychotic user at the time of initiation (when comparing users with and without Alzheimer's disease). Data on history of diagnosed depression (ICD-10 codes F32-39; ICD-9 codes 2961, 2968, 3004 and 3011; ICD-8 codes 29600, 30040, 30041 and 30110) were collected from the Hospital Discharge Register. Only diagnoses recorded before the time of Alzheimer's disease diagnosis/index date and for each antipsychotic user before the time of initiation were considered in the comparisons.

As the Prescription Register does not cover drugs used in nursing homes and hospitals, the date of long-term institutionalisation for each participant during the follow-up was obtained from the SII. In addition, hospital stays of more than 90 days were extracted from the Hospital Discharge Register maintained by the National Institute of Health and Welfare. Follow-up was censored at the start of long-term institutionalisation/hospitalisation, death or end of the study period, whichever occurred first. The formation of the study sample and reasons for exclusion and censoring are summarised in Fig. 1. Altogether, 33 matched controls had temporary reimbursement for Alzheimer's disease before 2006 and 511 were diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease during 2006–2009. These persons with their matched pairs were excluded from the analysis. In addition, pairs were excluded if either matched person with or without Alzheimer's disease had a history of schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders or bipolar disorder, used antipsychotics during the 2-year washout period or were in long-term institutional care at the start of follow-up. The final study sample consisted of 6087 matched pairs (n = 12 174). The mean age of the study sample at the time of Alzheimer's disease diagnosis was 79.4 years (range 42–97) and 63.8% were female (Table 1). The age, gender and regional distribution of the final sample (n = 12 174) did not differ from the initial study sample (n = 14 434).

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of the study sample.

TABLE 1 Description of the study sample and initiators of antipsychotic use

| Characteristic | Persons

with Alzheimer's disease (n = 6087) a |

Persons

without Alzheimer's disease (n = 6087) a |

χ2 or t | P | New users

with Alzheimer's disease (n = 1996) b |

New users

without Alzheimer's disease (n = 386) b |

χ2 or t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 79.4 (6.7) | 79.4 (6.7) | Matched | 79.8 (7.0) | 80.4 (7.5) | −1.32 | 0.19 | |

| Female, n (%) | 3885 (63.8) | 3885 (63.8) | Matched | 1284 (64.3) | 262 (67.9) | 1.79 | 0.18 | |

| Modified Charlson comorbidity | ||||||||

| index, n (%) | 1.08 | 0.58 | 0.08 | 0.96 | ||||

| Score = 0 | 3537 (58.1) | 3551 (58.3) | 1166 (58.4) | 226 (58.6) | ||||

| Score = 1 | 1650 (27.1) | 1675 (27.5) | 544 (27.3) | 103 (26.7) | ||||

| Score ≥2 | 900 (14.8) | 861 (14.1) | 286 (14.3) | 57 (14.8) | ||||

| Coronary artery disease/heart failure | 1611 (26.5) | 1572 (25.8) | 0.65 | 0.42 | 538 (27.0) | 102 (26.4) | 0.05 | 0.83 |

| COPD and asthma | 478 (7.9) | 520 (8.5) | 1.93 | 0.17 | 158 (7.9) | 39 (10.1) | 2.04 | 0.15 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 260 (4.3) | 240 (3.9) | 0.83 | 0.36 | 84 (4.2) | 15 (3.9) | 0.08 | 0.77 |

| Diabetes | 725 (11.9) | 624 (10.3) | 8.50 | 0.004 | 211 (10.6) | 26 (6.7) | 5.31 | 0.02 |

| Cancer | 198 (3.3) | 219 (3.6) | 1.10 | 0.30 | 59 (3.0) | 16 (4.2) | 1.50 | 0.22 |

| Initial antipsychotic, n (%) | 141.25 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Risperidone | NA | NA | 1000 (50.1) | 130 (33.7) | ||||

| Quetiapine | NA | NA | 556 (27.9) | 65 (16.8) | ||||

| Haloperidol | NA | NA | 146 (7.3) | 49 (12.7) | ||||

| Melperone | NA | NA | 109 (5.5) | 43 (11.1) | ||||

| Perphenazine | NA | NA | 44 (2.2) | 24 (6.2) | ||||

| Levomepromazine | NA | NA | 37 (1.9) | 30 (7.8) | ||||

| Other | NA | NA | 104 (5.2) | 45 (11.7) | ||||

| Benzodiazepine and related drug use, n (%) | 1178 (19.4) | 1131 (18.6) | 1.18 | 0.28 | 673 (33.7) | 177 (45.9) | 20.76 | <0.001 |

| Antidepressant use, n (%) | 1021 (16.8) | 392 (6.4) | 316.77 | <0.001 | 517 (25.9) | 105 (27.2) | 0.28 | 0.59 |

| History of diagnosed depression, n (%) | 305 (5.0) | 178 (2.9) | 34.77 | <0.001 | 115 (5.8) | 45 (11.7) | 17.95 | <0.001 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NA, not applicable.

a. Characteristics of the study sample were measured at the time of Alzheimer's disease diagnosis/index date in 2005.

b. Characteristics of new users were measured at the time of initiation of antipsychotic use.

Statistical analyses

Characteristics of persons with and without Alzheimer's disease were compared using χ2-test for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables. Poisson regression was used to compute incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% confidence intervals for every 6-month period to estimate the difference in incidences of antipsychotic use between persons with and without Alzheimer's disease. Logistic regression was used to analyse the relationship between initiation of antipsychotic use before Alzheimer's disease diagnosis and age and gender. All analyses were performed with SAS (Version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

During the follow-up, 1996 (32.8%) persons with Alzheimer's disease initiated antipsychotic use (Fig. 1). The incidence of new users was five times higher (IRR = 5.17; 95% CI 4.64–5.77) among persons with Alzheimer's disease compared with the matched persons without Alzheimer's disease, of which 386 (6.3%) initiated antipsychotic use.

At the time of Alzheimer's disease diagnosis (index date), a higher proportion of persons with Alzheimer's disease had history of diagnosed depression and diabetes, and were antidepressant users compared with persons without Alzheimer's disease (Table 1). There were no differences in the mean age, gender distribution and comorbidities between users with and without Alzheimer's disease at the time of initiation of antipsychotic use. New antipsychotic users without Alzheimer's disease used benzodiazepines and related drugs more frequently (45.9%) than users with Alzheimer's disease (33.7%, P<0.001). A higher proportion of antipsychotic users without Alzheimer's disease had history of diagnosed depression (11.7%) compared with new users with Alzheimer's disease (5.8%, P<0.001). A fourth of both new users with and without Alzheimer's disease used antidepressants at the time of initiation of antipsychotic use. The profile of antipsychotics prescribed was different between persons with and without Alzheimer's disease (P<0.001). Among persons with Alzheimer's disease use was initiated most frequently with risperidone (50.1%, 1000/1996) or quetiapine (27.9%, 556/1996). Similarly among new users without Alzheimer's disease, the most prevalent antipsychotic was risperidone (33.7%, 130/386) followed by quetiapine (16.8%, 65/386). Other antipsychotics comprised 22% of initiations for persons with Alzheimer's disease and 49% for persons without Alzheimer's disease.

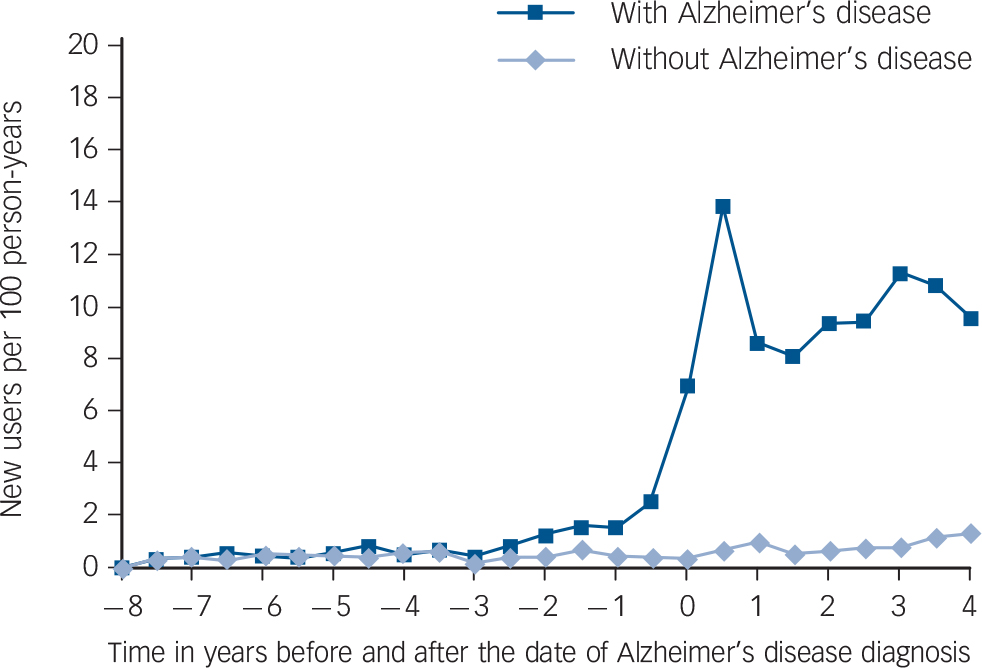

The rate of new users among persons with Alzheimer's disease significantly increased 2–3 years before Alzheimer's disease diagnosis compared with the rate among the controls without Alzheimer's disease (IRR = 2.09; 95% CI 1.05–4.16 for time period of −3 to −2.5 years before diagnosis; Fig. 2). The incidence of antipsychotic use was highest during the first 6 months after Alzheimer's disease diagnosis (13.9 new users per 100 person-years) and remained at a high level thereafter (8.6–11.3 new users per 100 person-years). However, the incidence of antipsychotic use among the controls without Alzheimer's disease remained stable during the 12-year follow-up ranging between 0.2 and 1.3 new users per 100 person-years. Among antipsychotic users with Alzheimer's disease, 71.5% of the use was initiated at the time of diagnosis and thereafter, whereas among the controls without Alzheimer's disease 44.8% of antipsychotic use was initiated after and 55.2% before the index date (P<0.001).

Fig. 2 Incidence of antipsychotic use in relation to diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease among persons with and without Alzheimer's disease.

The date of Alzheimer's disease diagnosis of the person with Alzheimer's disease was defined as the index date (point zero) for the matched control person without Alzheimer's disease.

A higher proportion of those who were aged 80 years or over at the time of diagnosis (33.4%) had initiated antipsychotic use before diagnosis compared with those aged less than 80 years (23.1%; OR = 1.64 95% CI 1.34–2.00 adjusted for gender). Of women with Alzheimer's disease, 30.1% initiated antipsychotic use before Alzheimer's disease diagnosis in comparison to 25.6% of men with Alzheimer's disease (P = 0.033). However, in a logistic regression analysis adjusted for age, gender was not significantly associated with initiating antipsychotic use before diagnosis (OR = 1.16; 95% CI 0.94–1.43).

Discussion

Principal findings

The incidence of antipsychotic use started to increase among persons with Alzheimer's disease already 2–3 years before Alzheimer's disease diagnosis which might indicate early behavioural and psychological symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. Behavioural and psychological symptoms are frequent in persons with mild cognitive impairment and these might be one of the earliest symptoms of Alzheimer's disease in some persons. Reference Lyketsos, Lopez, Jones, Fitzpatrick, Breitner and DeKosky1,Reference Rosenberg, Mielke, Appleby, Oh, Geda and Lyketsos31 Thus, behavioural and psychological symptoms in the prodromal phases of Alzheimer's disease could explain the increased use of antipsychotics before the diagnosis. On the other hand, the increased use of antipsychotics before the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease could partly result from the treatment of delirium. Based on previous research, delirium increases the risk for being diagnosed with dementia. Reference Rockwood, Cosway, Carver, Jarrett, Stadnyk and Fisk32,Reference Rahkonen, Luukkainen-Markkula, Paanila, Sivenius and Sulkava33 In addition, delirium increases cognitive decline and might be a risk factor for new-onset dementia. Reference Davis, Muniz Terrera, Keage, Rahkonen, Oinas and Matthews34 As the neuropathological process of Alzheimer's disease begins decades before symptoms' onset and fulfilment of diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer's disease, 35 the observed increase in the incidence of antipsychotic use 2–3 years before diagnosis could not have increased the risk of Alzheimer's disease. However, antipsychotic use might have accelerated the emergence and exacerbation of symptoms by declining cognition. Reference Vigen, Mack, Keefe, Sano, Sultzer and Stroup14,Reference Rosenberg, Mielke, Han, Leoutsakos, Lyketsos and Rabins15

The majority (72%) of antipsychotic use was initiated at the time of Alzheimer's disease diagnosis and thereafter. This is likely to be related to the increased incidence of BPSD and delirium after the diagnosis. In addition, the threshold of prescribing antipsychotics for older people might be lower after the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease, although guidelines recommend cautious and limited use. Reference Rabins, Blacker, Rovner, Rummans and Schneider20–22 The highest rate of new users was observed during the first 6 months after Alzheimer's disease diagnosis. The finding of distinct increase in incidence of use 6 months before and after Alzheimer's disease, diagnosis is similar to results of Martinez et al Reference Martinez, Jones and Rietbrock36 who found a sharp increase in prevalence of antipsychotic use around the time of diagnosis among community-dwelling persons with dementia in the UK.

Those aged 80 years or over at the time of diagnosis were more likely to have initiated antipsychotic use before diagnosis compared with those aged less than 80 years. This may indicate that persons who were aged 80 or above at the time of diagnosis were more likely to have BPSD requiring antipsychotic use before diagnosis. On the other hand, physicians may have been more likely to treat these persons symptom-based with antipsychotics and the diagnosis might have been delayed. Although men with Alzheimer's disease are more likely to use more than one antipsychotic concomitantly and use antipsychotics with higher doses than women, Reference Taipale, Koponen, Tanskanen, Tolppanen, Tiihonen and Hartikainen37,Reference Taipale, Koponen, Tanskanen, Tolppanen, Tiihonen and Hartikainen38 a higher proportion of women initiated antipsychotic use before Alzheimer's disease diagnosis. However, this association did not persist after adjusting for age.

Rationality of antipsychotic prescribing

The Finnish current care guideline recommends that all persons with Alzheimer's disease should be treated with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and/or memantine unless there is a specific contra-indication. 21 The highest rate of new antipsychotic users occurred directly after Alzheimer's disease diagnosis which is also the time when acetylcholinesterase inhibitor therapy is initiated and its dose is optimised. As antipsychotics may further impair cognitive function, Reference Vigen, Mack, Keefe, Sano, Sultzer and Stroup14,Reference Rosenberg, Mielke, Han, Leoutsakos, Lyketsos and Rabins15 the rationality of initiating antipsychotic use when trying to obtain the best response to acetylcholinesterase inhibitor therapy is questionable. In addition to poor cognitive function, Reference Vigen, Mack, Keefe, Sano, Sultzer and Stroup14,Reference Rosenberg, Mielke, Han, Leoutsakos, Lyketsos and Rabins15 antipsychotic use has been associated with increased mortality and serious adverse drug events like strokes, extrapyramidal symptoms and hip fractures Reference Schneider, Dagerman and Insel6–Reference Wu, Wang, Gau, Tsai and Cheng12 which warrants careful weighing of benefits and risks for the individual patient.

The Finnish current care guideline on memory disorders recommends antipsychotic use only for the most severe BPSD including severe aggression and psychotic symptoms. 21 It is also stated that antipsychotics should not be used in the treatment of BPSD for which they are not efficacious for, including hoarding, wandering, yelling, sexual disinhibition and eating inedible objects. We do not know whether physicians prescribe antipsychotics according to these recommendations in clinical practice. The high rate of antipsychotic use among persons with Alzheimer's disease observed in this study suggests otherwise. It seems that antipsychotics are not prescribed only for severe aggression and severe psychotic symptoms but also for other behavioural and psychological symptoms without evidence of benefits. However, some of the observed rate of antipsychotic use among persons with Alzheimer's disease could be due to delirium as dementia is a major risk factor for delirium. Reference Inouye, Westendorp and Saczynski39

Of the controls without Alzheimer's disease 6% initiated antipsychotic use during the follow-up. The Prescription Register data did not include indications for antipsychotic use. At the time of initiation of antipsychotic use, a higher proportion of controls without Alzheimer's disease used benzodiazepines and related drugs and had history of diagnosed depression compared with antipsychotic users with Alzheimer's disease. Thus, possible reasons for antipsychotic use among the controls without Alzheimer's disease could be treatment of depression, anxiety or insomnia. Some of the controls without Alzheimer's disease could have dementia due to causes other than Alzheimer's disease such as vascular dementia. However, Alzheimer's disease is the most common form of dementia accounting up to 80% of the cases. 35 Despite the use of antipsychotics among the controls, the findings of this study clearly show alarmingly high incidence of antipsychotic use among persons diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease.

In our study, risperidone was the most frequently initiated antipsychotic among persons with Alzheimer's disease. This is in line with the fact that risperidone is the only antipsychotic with approved indication for treatment of severe aggression in persons with Alzheimer's disease in Finland. A quarter of the users with Alzheimer's disease initiated antipsychotic use with quetiapine, although randomised controlled trials have not found evidence for the benefit of quetiapine use in the treatment of psychosis, agitation and global behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia. Reference Maher, Maglione, Bagley, Suttorp, Hu and Ewing19 Quetiapine is known to be used in the off-label treatment of insomnia Reference Hermes, Sernyak and Rosenheck40 and based on our clinical experience it is also frequently used for this indication in Finland which could explain the high rate of quetiapine use. However, antipsychotics should not be used in the treatment of insomnia. 41

Strengths and limitations of the study

Important strengths of this study were the nationwide sample, clinically and imaging verified diagnoses of Alzheimer's disease and the ability to examine the incidence of antipsychotic use longitudinally over 12 years. A general limitation of Prescription Register data is that it is not known whether the dispensed drugs were actually taken. However, the validity of the Prescription Register in measuring exposure to antipsychotics among older people has been previously confirmed. Reference Rikala, Hartikainen, Sulkava and Korhonen42 The Prescription Register does not cover drugs used in hospitals and nursing homes which was taken into account by censoring follow-up at the start of long-term institutionalisation/hospitalisation. This may have underestimated the incidence of antipsychotic use as antipsychotic use is known to be higher in institutional settings. Reference Rattinger, Burcu, Dutcher, Chhabra, Rosenberg and Simoni-Wastila5 Further, we did not have information on the indication and appropriateness of antipsychotic use and the severity of BPSD and Alzheimer's disease. Persons with history of schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders or bipolar disorder were excluded to remove the effect of these diagnoses on the incidence of antipsychotic use. The strength of our study was the ability to compare the incidence of antipsychotic use among persons with Alzheimer's disease to the matched controls. Thus, the changes in incidence among persons with Alzheimer's disease are likely to be related to the symptoms associated with Alzheimer's disease as the incidence among the controls remained stable during the 12 years.

Implications for clinical practice and research

The high rate of antipsychotic initiations directly after Alzheimer's disease diagnosis is a concern as antipsychotics have been associated with an increased risk of serious adverse drug events. Instead of symptom-based treatment with antipsychotics there is a need for comprehensive clinical assessment to identify the underlying causes such as cognitive impairment. Future studies should assess the type and severity of BPSD for which antipsychotics are used around the time of diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease and whether the use is avoidable. Studying the feasibility and effectiveness of non-pharmacological approaches in representative cohorts is crucial to limit the use of antipsychotics only for most severe symptoms.

Funding

The research was funded by University of Eastern Finland Faculty of Health Sciences strategic funding. The funders had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.