Diagnostic precision is a fine thing. Its potential benefits are considerable - improved communication between health professionals, better research into causes and prevention, and the development of specific treatments. But is the time really right to create a new diagnosis of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), or are we simply in danger of creating a false dichotomy?

Non-suicidal self-injury - where did it come from and what does it mean?

In this issue Butler & Malone discuss the current criteria for NSSI in some detail. Reference Butler and Malone1 However, the concept is not new - in the 1960s clinicians in the USA described seeing increasing numbers of people who cut themselves in order to feel better rather than seeking to die. Reference Graff and Mallin2 Recent developments in terminology have occurred in the context of a growing recognition that some individuals, young people in particular, were injuring themselves but did not meet the criteria for borderline personality disorder or psychiatric illness. A diagnosis of NSSI would mean that adolescents might avoid a potentially inappropriate personality disorder label, while still having a formal diagnosis for which they could receive treatment. So, the motives behind the introduction of NSSI were admirable. Unfortunately, the evidence base is weak. Few studies have been carried out in adults, the majority of work has been conducted in North America Reference Muehlenkamp, Claes, Havertape and Plener3 and there is a lack of high-quality, large-scale longitudinal data. Despite this, the term NSSI has gained popularity, especially in the USA, and it has been proposed for inclusion in DSM-5, with the Childhood and Adolescent Disorders Work Group developing the diagnostic criteria. Whether NSSI makes its way into the published version of DSM-5 in May 2013 or not, there are potential problems with the term itself.

First and most importantly, the prefix ‘non-suicidal’ is misleading because of the strong association between NSSI and suicidal behaviour - in one study of a community sample of adults, over a third of respondents reported that they had engaged in NSSI while actually experiencing suicidal thoughts. Reference Klonsky4 Longitudinal research has identified NSSI as one of the most important risk factors for suicide attempts. Reference Andover, Morris, Wren and Bruzzese5 Self-cutting is the most common method of NSSI and a behaviour that is often regarded as being of limited seriousness by clinical services. However, there is evidence that self-cutting that results in hospital treatment is actually associated with greater risk of eventual suicide than self-poisoning in both adults Reference Cooper, Kapur, Webb, Lawlor, Guthrie and Mackway Jones6 and adolescents. Reference Hawton, Bergen, Kapur, Cooper, Steeg and Ness7 Of course, these findings may not apply to individuals who cut themselves and do not present to clinical services.

Second, there is the paradox that self-poisoning can never be included as NSSI, even when patients report episodes as categorically non-suicidal. Reference Andover, Morris, Wren and Bruzzese5 Hospital-based studies suggest that as many as 25-50% of those who self-poison may report no suicidal intent. Reference Kapur, Cooper, King-Hele, Webb, Lawlor and Rodway8,Reference O'Connor, Whyte, Fraser, Masterton, Miles and MacHale9 Non-suicidal self-injury is restricted to methods such as cutting, burning, stabbing, hitting or excessive rubbing, which leaves non-suicidal self-poisoning in the classificatory wilderness.

Third, there is the point that methods of self-harm change over time. Those with index episodes of NSSI may subsequently poison themselves and vice versa. In a large cohort study of over 7344 individuals presenting to general hospitals in England and followed up for an average of 9 months, 1234 repeated self-harm and a third of these switched methods. Reference Lilley, Owens, Horrocks, House, Noble and Bergen10 Method switching was particularly common in people who cut themselves at their index episode - over 60% changed methods, most frequently to poisoning.

How can research into self-harm help us?

Terms for non-fatal suicidal behaviour such as ‘parasuicide’ and ‘attempted suicide’ were superseded in the 1970s in the UK by ‘deliberate self-harm’ in recognition that not all episodes involved definite suicidal intent. More recently, the prefix ‘deliberate’ has been largely dropped because of concerns that it was judgemental and because the extent to which the behaviour is intentional is not always clear. 11 Self-harm refers to self-injury or self-poisoning regardless of apparent motivation. Reference Hawton, Harriss, Hall, Simkin, Bale and Bond12 Can research using such intent-free definitions shed any light on the phenomenon of NSSI?

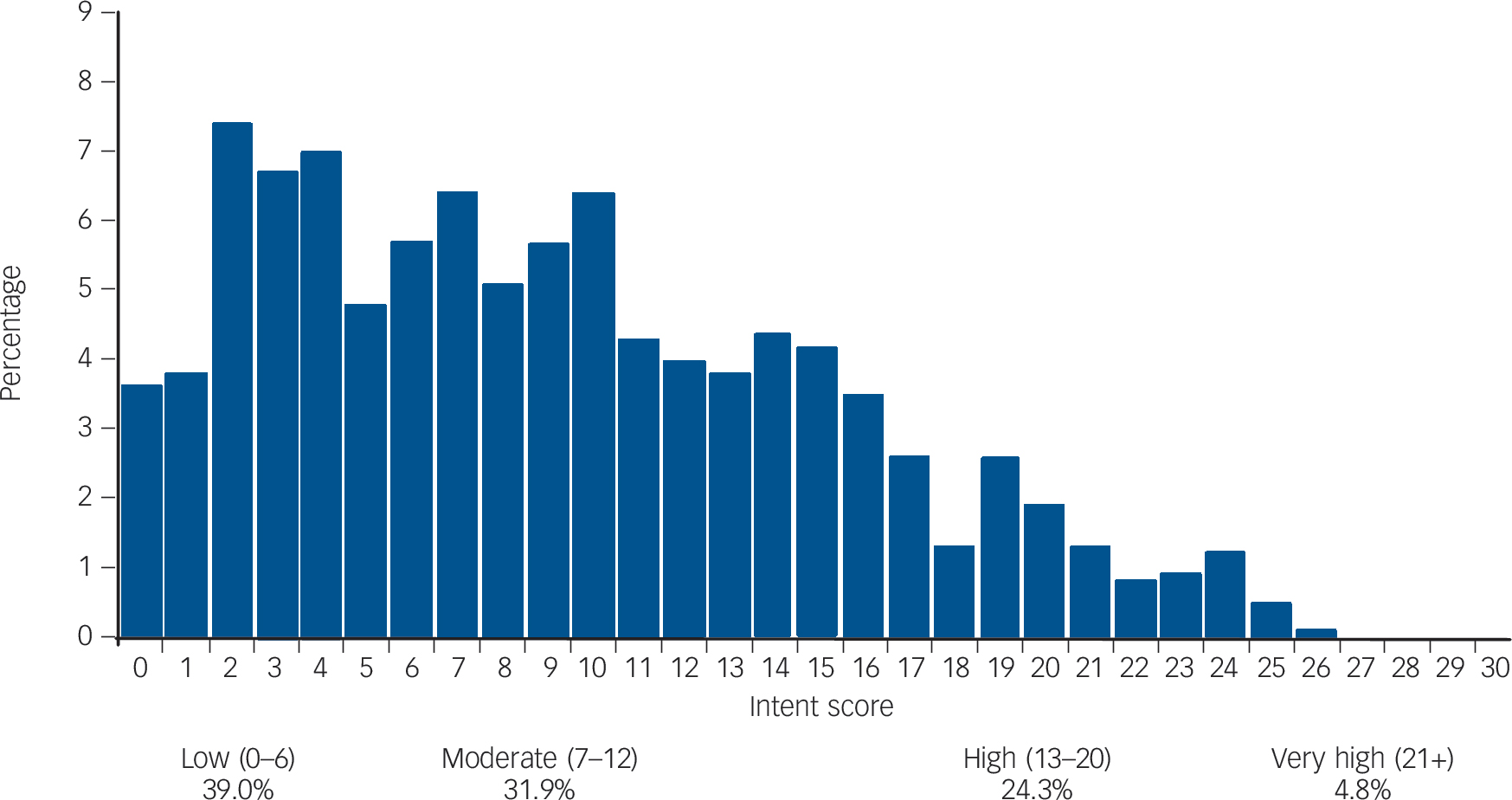

If NSSI exists as a discrete entity one might expect suicidal intent in people who have self-harmed to show a bi-modal distribution, with some individuals clearly ‘suicidal’ and others clearly ‘non-suicidal’. In fact, suicidal intent appears to be continuously distributed in clinical populations with no easily identifiable cut-offs. Figure 1 shows the distribution of scores on the Suicidal Intent Scale for over 700 individuals presenting to hospital in Oxford with self-harm. Reference Hawton, Casey, Bale, Rutherford, Bergen and Simkin13 However, a continuous distribution does not necessarily preclude there being discrete groups, and statistical techniques (for example, taxometric analyses or latent class analysis) might help to determine the extent to which NSSI and attempted suicide are qualitatively different or not. There is also the related issue of ambivalence. In one study, over 40% of young people said they did not care whether they lived or died at the time of the self-harm episode. Reference Hawton, Cole, O'Grady and Osborn14

We might also reasonably expect to be able to distinguish between NSSI and ‘genuine’ suicide attempts on the basis of outcome. However, the best evidence suggests that even episodes of self-harm with no reported suicidal intent are related to an elevated risk of repeat self-harm and suicide compared with the general population. Reference Cooper, Kapur, Webb, Lawlor, Guthrie and Mackway Jones6,Reference Kapur, Cooper, King-Hele, Webb, Lawlor and Rodway8 In a cohort study of nearly 8000 individuals presenting with overdose or self-injury to four emergency departments in Greater Manchester, there was no significant difference in subsequent suicide mortality between individuals who indicated that they did or did not wish to die at the time of the attempt. Reference Cooper, Kapur, Webb, Lawlor, Guthrie and Mackway Jones6

There is an argument that one of the main distinctions between suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury is the motivation underlying the act - a wish to die as opposed to seeking relief from distressing symptoms. However, self-injury as a whole is often characterised by multiple motivations existing simultaneously. In a study of over 30 000 adolescents in seven countries, over 80% of those who had harmed themselves in the previous month reported more than one reason for self-harm. Reference Scoliers, Portzky, Madge, Hewitt, Hawton and De Wilde15 Common reasons included wanting to get relief from a terrible state of mind, wanting to die and wanting to punish oneself. Motivations may also change from one episode to the next. This will be familiar to clinicians and is explicitly acknowledged in UK guidance that stresses that each episode of self-harm should be assessed in its own right. 11 This guidance recommends that the presence/absence of suicidal intent associated with both current and past episodes of self-harm should be assessed. Self-reported motivation may even change within the same episode. The quotes in the Appendix from a qualitative study of individuals who had self-harmed in Manchester Reference Cooper, Hunter, Owen-Smith, Gunnell, Donovan and Hawton16 help to illustrate this. Underlying motivations may be unclear even to the person who has harmed themselves and clinicians and service users may have very different views on the degree of suicidal intent associated with the same episode of self-harm. Reference Hawton, Cole, O'Grady and Osborn14 One important question is whose view - the doctor's or the patient's - should determine whether a behaviour is NSSI or not? Basing a diagnosis on a construct as fluid as motivation is clearly problematic.

Fig. 1 The distribution of scores on the Beck Suicide Intent Scale in 771 individuals presenting consecutively to a single general hospital in Oxford with self-harm in 2009. Reference Hawton, Casey, Bale, Rutherford, Bergen and Simkin13

The sample included all ages (range 11-91 years), 60% were aged under 35 years, and 61% of individuals were female.

Conclusion

Much of the literature on NSSI has focused on young people. Comparatively few studies have been carried out in adults. Self-harm research suggests that the NSSI concept may have limited usefulness in practice but much of this work has been carried out in secondary care or emergency department settings. It is certainly possible that NSSI has greater validity in community samples of young people. What nearly everyone seems to agree on is that we need more research. Could the creation of a new diagnostic category help us to understand the incidence and natural history of this phenomenon and ultimately inform better treatment? Perhaps, but this would be particularly challenging in the context of the changing motivations and methods that characterise self-injury. There is also the well-rehearsed argument that whether we prefer the terms self-harm, or NSSI, or suicidal behaviour disorder (that has recently appeared in the proposed draft of DSM-5), these are all behaviours and not disorders. This is part of a criticism of disease classification systems that goes much wider than the current debate. We think that there are potential problems with creating a new diagnosis of NSSI for which we have no proven treatments and which could stigmatise large numbers of young people unnecessarily. Reference De Leo17 This is a risk that is all the more dubious given the fact that self-harming behaviour mostly ceases as adolescents mature. Reference Moran, Coffey, Romaniuk, Olsson, Borschmann and Carlin18

There are also obvious difficulties in labelling behaviours as definitively non-suicidal when they greatly increase the risk of future self-inflicted death. Given the pressure on front-line clinical services, the danger of an attempted suicide/NSSI dichotomy is that those with NSSI will be given lower priority and receive poorer treatment than other patients. Although self-harm is not a perfect descriptor, we might well be better off sticking with the terminology we currently have.

Appendix

Changing suicidal intent between episodes and within episodes from a qualitative study of self-harm

Motivations change between episodes:

‘So basically the first time I did it I didn't have, I don't think I had, suicidal intent if I'm honest, but it was definitely more a cry for attention really, I needed help… But when I took the second overdose that was with suicidal intent, I had had enough I was burned out so that's why I took as much drugs as I could physically tolerate.’ (Male respondent, aged 20)

but also within episodes:

‘At first it was about ending… life. But then I started thinking about my Gran and thinking my mum letting me down in the last day and my Nan leaving me when she promised me she wouldn't… all these other things that I was thinking - why me, you know?… then [I] started to take the pills in anger.’ (Female respondent, aged 26)

These data are unpublished and were collected as part of a qualitative study described in Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Hunter, Owen-Smith, Gunnell, Donovan and Hawton16 The sample consisted of 11 service users (6 female, 5 male, age range 18-53 years).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.