Transcultural studies of schizophrenia conducted under the auspices of the World Health Organization found that lack of insight was an almost invariable feature of acute and chronic schizophrenia, regardless of setting. 1,Reference Wilson, Ban and Guys2 A categorical or unidimensional view of insight has given way to more multidimensional perspectives, Reference Amador and David3 which appear to be adaptable to different cultural settings. Reference Saravanan, Jacob, Prince, Bhugra and David4,Reference Saravanan, Jacob, Johnson, Prince, Bhugra and David5 In the past decade, instruments with more sensitivity than single-item measures have been devised to assess and quantify insight for research purposes, and important associations with psychopathological, social and biological factors have been replicated. Reference Amador and David3

Regarding the relation between insight and outcome of schizophrenia, studies of prevalent cases are generally uninformative since they tend to be biased towards patients with poorer outcomes. Prospective studies are less common, although the results tend to point towards better insight being associated with better prognosis. Reference David, Amador and David6 However, these studies suffer from the use of a wide variety of unvalidated insight scales and variable outcome measures. Reference Lincoln, Lullmann and Rief7 A few studies have explored insight as a predictor of outcome in first-episode psychosis. Reference David, van Os, Jones, Harvey, Foerster and Fahy8–Reference Drake, Dunn, Tarrier, Bentall, Haddock and Lewis10 For example, David et al showed that a single insight item predicted employment status over 2 years in a recent-onset mixed psychosis cohort from south London. Reference David, van Os, Jones, Harvey, Foerster and Fahy8 Drake et al showed that self-rated insight was a significant predictor of readmission over an 18-month period. Reference Drake, Dunn, Tarrier, Bentall, Haddock and Lewis10

We investigated prospectively a cohort of patients with a first episode of schizophrenia in Vellore, South India (see our earlier study). Reference Saravanan, Jacob, Johnson, Prince, Bhugra and David5 We sought to determine whether insight assessed on admission, or early improvement in insight, predicted good outcome independently of duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and demographic factors such as gender, and whether any such change is associated with or independent of change in psychopathologic symptoms.

Method

In a prospective, longitudinal cohort study, data were collected on insight, psychopathology and 1-year course of schizophrenia in consecutive patients making their first contact with mental health services. Three assessments were undertaken: at baseline and at 6 months and 12 months. Our analysis used the baseline and follow-up data.

Study site

Tamil Nadu is one of the most industrialised states in India. The primary language is Tamil. Tamil Nadu has better education, health and development indices than most other Indian states: 73% of the population is literate compared with 65% for the whole country. 11 Vellore district (area 4314 km2, population 3 026 432) is situated in the north central part of the state. Kaniyambadi Block, one of 12 administrative blocks in Vellore district, was the study site. The study took place in the Department of Psychiatry of the Christian Medical College, Vellore. The 100-bed hospital adult psychiatry unit provides short-term care for patients with different organic disorders, substance use, psychoses, neuroses and adjustment problems. The emphasis is on a multidisciplinary approach and eclectic care using a wide variety of therapies. The hospital has a daily out-patient clinic serving 200–250 patients.

Sample and procedure

The study group consisted of patients living within a 100 km radius of the study site. Patients were carefully screened for a diagnosis of schizophrenia and then interviewed by a research psychiatrist (B.S.) at intake using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–III–R – Patient version (SCID–P) to confirm the diagnosis. Reference Spitzer, Williams and Gibbon12 Patients with a primary diagnosis of substance use disorder, mood disorder or organic mental disorder were excluded (for details see reference Reference Saravanan, Jacob, Johnson, Prince, Bhugra and David5). Patients meeting inclusion criteria and providing written consent were interviewed as soon as possible, with all patients assessed within a week of starting treatment for psychosis. All patients were interviewed again 6 months and 12 months after the initial assessment. Patients were informed that the purpose of the study was to assess their level of awareness about their illness, but they were unaware of the study's specific hypotheses.

Assessment measures

Social and demographic variables were recorded, including years of education. Patients were interviewed by trained raters using the Tamil version of SCID–P. At baseline we used the Lifetime version of the interview. The Schedule for the Assessment of Insight – Expanded version (SAI–E) with its three dimensions (awareness of illness, relabelling and compliance), the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) were used at baseline and at each follow-up wave. Reference David, van Os, Jones, Harvey, Foerster and Fahy8,Reference David, Buchanan, Reed and Almeida13–Reference Ventura, Lukoff, Neuchterlein, Liberman, Green and Shaner15 As before, we used the ‘guilt’, ‘low mood’ and ‘suicidality’ items of the BPRS added together as a proxy measure of depression. Duration of untreated psychosis was defined as the interval from the occurrence of prominent psychotic symptoms to first contact with psychiatric services. This onset date was synthesised from the SCID–P interview, which included chronology of psychotic symptoms and significant other collateral information. Finally, whether or not the patient consulted a traditional healer prior to coming to the hospital was noted as a potential indicator of early illness awareness.

We planned to use clinically defined ‘broad’ psychosis outcomes (full remission, remission with deficits, and relapse) as the primary outcome measure, in addition to the repeated measures of GAF (baseline, 6-month and 12-month assessments). Remission is a state following a psychotic episode in which there is no positive or negative symptom for at least 30 days; relapse is the occurrence of at least one positive symptom or two negative symptoms after a period of remission; remission with deficits is the presence of one negative symptom or of social or occupational deficits after a period of remission. Two of the researchers (B.S. and K.S.J.) agreed on the ratings of remission and relapse, basing these on criteria used in the Study of Factors Associated with the Course and Outcome of Schizophrenia (SOFACOS), 16,Reference Verghese, John, Rajkumar, Richard, Sethi and Trivedi17 and the Determinants of Outcome of Severe Mental Disorders (DOSMeD), Reference Jablensky, Sartorius, Emberg, Anker, Korten and Cooper18 applied to information extracted from clinical case notes. We used the broad psychosis outcome to tabulate the regression models to make this study more relevant to clinical practice in low- and middle-income countries.

Statistical analysis

The three broad psychosis outcome variables were collapsed to yield two: remission and relapse. Remission was defined as being symptom-free, and relapse was defined as meeting criteria for a schizophrenic episode after meeting criteria for remission in a previous follow-up period. We used general linear modelling (GLM) analysis in SPSS version 15 for Windows, to test whether baseline insight or psychopathology (BPRS score, model 1), or change in insight or psychopathology at 0–6 months (model 2) or at 6–12 months (models 3 and 4) predicted good outcome using GAF score as a continuous outcome measure at 12 months, controlling for sociodemographic and clinical variables (gender, marital status, employment, urbanicity, DUP, traditional healer visit plus baseline insight and psychopathology scores where appropriate). A second set of logistic regressions, each with the same model structure as above, was performed with clinical outcome (complete remission or relapse) as the dependent variable, entering the same independent variables and with the same controls. Interactions between insight and outcome and significant covariates were checked in the modelling. Model fits were checked by examining partial residual plots.

Results

Of 196 patients with first-episode psychosis who attended hospital clinics between 1 January 2003 and 30 January 2004, a total of 188 met the study criteria. Of these patients, 57 were excluded (37 owing to psychopathology precluding interview), 14 did not attend interview and 6 refused. Baseline interviews were administered to the 131 remaining consecutive patients who met the inclusion criteria. Of these patients, 72 (55%) were men and 59 (45%) were women, of mean age 29.5 years (s.d. = 7.2). Most were single (48%), unemployed (70%), lived in rural areas (80%) during intake and had been brought to hospital by relatives (Table 1). The DUP was long and the distribution skewed (mean 95.5 weeks, median 48, range 2–720). The vast majority of patients were treated with olanzapine (10–15 mg). The main findings from the baseline data have been published elsewhere. Reference Saravanan, Jacob, Johnson, Prince, Bhugra and David5,Reference Saravanan, Jacob, Deepak, Bhugra, Prince and David19

Table 1 Patient characteristics at baseline and at 12-month follow-up

| Baseline assessment (n = 131) | 12-month follow-up (n = 115) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 29.5 (7.2) | 29.5 (7.0) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 72 (55) | 62 (54) |

| Female | 59 (45) | 53 (46) |

| Religion,a n (%) | ||

| Hindu | 115 (88) | 102 (89) |

| Muslim | 4 (3) | 2 (2) |

| Christian | 11 (8) | 10 (9) |

| Residence, n (%) | ||

| Rural | 105 (80) | 92 (80) |

| Urban | 26 (20) | 23 (20) |

| Literacy, n (%) | ||

| Illiterate | 22 (17) | 18 (16) |

| Read only | 9 (7) | 7 (6) |

| Read and write | 100 (76) | 90 (78) |

| Age at onset of illness, years: mean (s.d.) | 27.8 (6.8) | 27.9 (6.8) |

| Duration of untreated psychosis, weeks: mean (s.d.) | 95.5 (134.2) | 94.6 (127.4) |

| Status, n (%) | ||

| Brought by relatives | 115 (88) | 104 (90) |

| Self-presenting | 16 (12) | 11 (10) |

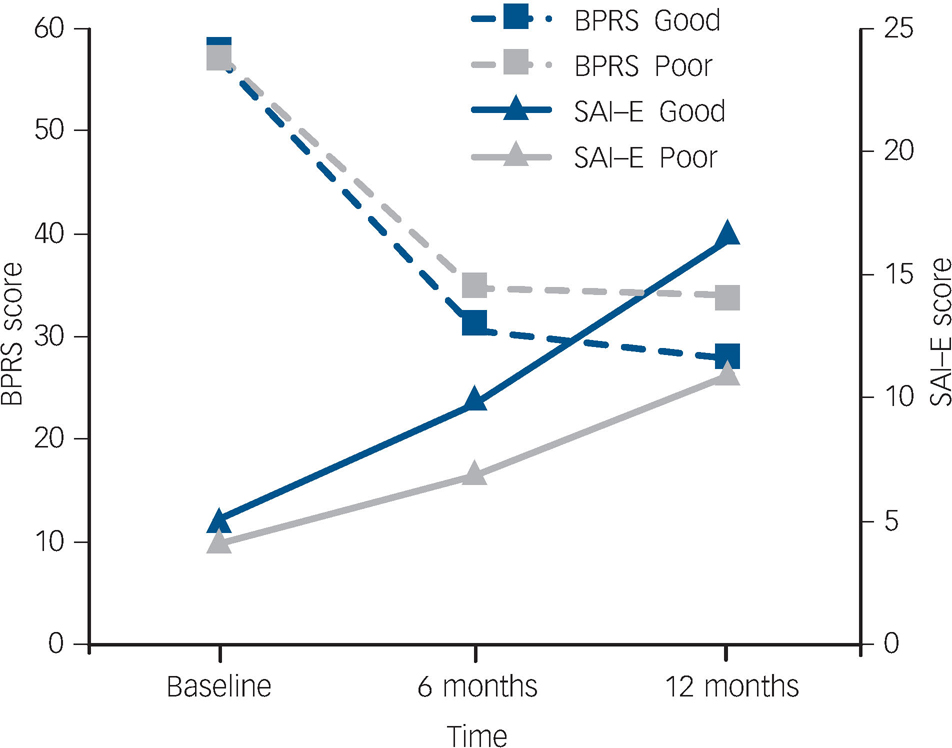

At 6 months, 103 (79%) patients were interviewed and 115 (88%) were assessed at the end of 1 year. The baseline, 6-month and 12-month follow-up mean scores on the BPRS, GAF and SAI–E scales showed general improvement in all clinical measures, as expected (Table 2). Interestingly, it appears that the greatest improvement in BPRS and GAF scores occurred within the first 6 months, whereas insight improved at a steadier rate over 12 months (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Plot of psychopathological symptoms (Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, BPRS) and insight (Scale for Assessment of Insight – Expanded version, SAI–E) scores from baseline to 12-month follow-up by clinical outcome.

Baseline scores are similar but outcome groups diverge at the 6-month point. Note that BPRS scores fall as symptoms improve and SAI–E scores rise as insight improves.

Table 2 Scores on clinical measures at the three assessment points

| Baseline assessment Mean (s.d.) | 6-month follow-up Mean (s.d.) | 12-month follow-up Mean (s.d.) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAF | 28.7 (8.19) | 56.3 (11.5) | 63 (13.9) |

| BPRS total score | 56.7 (5.2) | 32.5 (6.9) | 30.9 (6.4) |

| SAI—E total score | 4.7 (4.57) | 8.5 (5.2) | 13.9 (7.1) |

Good and poor outcomes

Table 3 summarises the rates of remission and relapse found in the cohort over the year of follow-up. Of the 115 patients assessed, half (n = 58) had experienced complete remission of symptoms and half (n = 57) experienced remission with deficits by the 12-month follow-up. At the 6-month assessment, 1 patient had died, 15 had withdrawn and 12 could not be traced, and at 1 year there was 1 further death, 4 patients withdrew and a further 11 could not be traced. Fourteen patients (12%) relapsed during the entire 12-month follow-up period. Most of those assessed at 12 months (96%, n = 110) were found to satisfy the study criteria for schizophrenia at any time during the year of follow-up. In addition, 65% (n = 75) were in regular contact for the monthly follow-up appointments.

Table 3 Remission and relapse 1 year after first contact with psychiatric services

| Outcome | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Complete remission | 58 (50) |

| Relapse | 2 |

| No relapse | 56 |

| Remission with deficits | 57 (50) |

| Relapse | 12 |

| No relapse | 45 |

Insight and psychopathology

Pearson correlation coefficients between insight and BPRS scores at baseline and follow-up assessment points were examined. At the baseline assessment there was no significant correlation between total BPRS score and total insight score. However, a significant albeit weak negative correlation between the relabelling dimension of the SAI–E and BPRS was observed (Pearson's r = –0.2, P = 0.04). In addition, the depression subscale score (mean = 6.5, s.d. = 2.3) showed a weak positive correlation with SAI–E total score and illness awareness items (r = 0.17 and r = 0.19 respectively, P≤0.05).

At follow-up the pattern of associations was rather different: there was a moderate significant negative correlation between total BPRS score and total insight score at 1 year (r = –0.3, P = 0.007). Lower BPRS scores were significantly associated with increase in the awareness (r = –0.35, P = 0.01) and treatment dimensions (r = –0.34, P = 0.01) at 6 months and the awareness (r = –0.4, P = 0.01), relabelling (r = –0.5, P = 0.01) and treatment dimensions (r = –0.5, P = 0.01) at 1 year. To find out whether changes in insight might be accounted for by improvement in clinical status, correlations between change scores in BPRS (baseline minus follow-up) and change scores in insight measures were obtained. The correlation coefficient was r = 0.3 (P = 0.01).

Predictors of outcome

Both regression analyses identified duration of untreated psychosis and early changes in insight and psychopathology as predictors of good outcome (Tables 4 and 5). Table 4 shows predictors of GAF and Table 5 shows predictors of clinically classified good outcome at 12 months. Duration of untreated psychosis is a significant predictor in both analyses in all four models, along with changes in psychopathology (BPRS) and insight (SAI–E) scores between baseline and 6 months (model 2). Interestingly, neither baseline insight nor baseline psychopathology was predictive of outcome (model 1). Similarly, changes between 6 months and 12 months were not related to outcome, with or without adjustment for baseline psychopathology/insight (models 3 and 4; Fig. 1).

Table 4 Predictors of good outcome in first-episode schizophrenia using Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score as the primary outcome: general linear model analysis

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a Beta | Model 2b Beta | Model 3c Beta | Model 4d Beta | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | |

| Age | -1.05 | 6.77 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.002 | 0.96 | 0.12 | 0.73 | 1.30 | 0.26 | 1.34 | 0.25 |

| Gendere | 0.57 | -1.13 | -0.40 | -0.77 | 0.04 | 0.85 | 0.19 | 0.66 | 0.02 | 0.88 | 0.08 | 0.77 |

| Marital statusf | -1.76 | -3.37 | -0.99 | -0.42 | 0.32 | 0.57 | 1.60 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.73 | 0.02 | 0.89 |

| DUP | -3.31 | -3.45 | -3.90 | -3.75 | 9.5 | 0.003* | 11.50 | 0.001* | 13.6 | 0.001* | 12.2 | 0.001* |

| Traditional healerg | 2.12 | 1.33 | 2.72 | 2.73 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.62 | 0.98 | 0.33 | 0.99 | 0.32 |

| Education | -0.32 | -0.33 | -0.30 | -0.31 | 0.86 | 0.36 | 1.24 | 0.27 | 0.90 | 0.35 | 0.95 | 0.33 |

| BPRS score | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 9.69 | 4.56 | 0.12 | 0.73 | 0.03 | 0.86 | ||||||

| Change 0-6 months | -0.43 | 0.66 | 0.003* | |||||||||

| Change 6-12 months | -0.30 | -0.30 | 0.66 | 0.08 | 3.10 | 0.08 | ||||||

| SAI—E score | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 0.43 | 0.24 | 2.0 | 0.16 | 77 | 0.38 | ||||||

| Change 0-6 months | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.001* | |||||||||

| Change 0-12 months | 0.24 | 0.24 | 1.66 | 0.20 | 1.61 | 0.21 | ||||||

Table 5 Predictors of good outcome (remission without relapse) in first-episode schizophrenia using clinically defined outcome criteria: logistic regression analysis

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a CI | Model 2b CI | Model 3c CI | Model 4d CI | OR | P | OR | P | OR | P | OR | P | |

| Age | 0.90-1.03 | 0.88-1.03 | 0.92-1.06 | 0.92-1.06 | 0.97 | 0.32 | 0.95 | 0.23 | 0.98 | 0.66 | 0.98 | 0.66 |

| Gendere | 0.33-2.01 | 0.23-1.68 | 0.28-1.88 | 0.28-1.92 | 0.81 | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.34 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 0.74 | 0.53 |

| Marital statusf | 0.24-1.56 | 0.16-1.28 | 0.25-1.80 | 0.23-1.81 | 0.61 | 0.30 | 0.45 | 0.13 | 0.67 | 0.42 | 0.65 | 0.41 |

| DUP | 0.99-1.00 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.99 | 0.04* | 0.99 | 0.05* | 0.99 | 0.03* | 0.99 | 0.03* |

| Traditional healerg | 0.31-1.79 | 0.23-1.76 | 0.32-2.17 | 0.32-2.18 | 0.75 | 0.51 | 0.64 | 0.39 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 0.84 | 0.72 |

| Education | 0.85-1.06 | 0.84-1.07 | 0.85-1.07 | 0.85-1.07 | 0.95 | 0.37 | 0.95 | 0.23 | 0.95 | 0.42 | 0.95 | 0.42 |

| BPRS score | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 0.93-1.08 | 0.90-1.07 | 0.92-1.08 | 0.92-1.08 | 1.00 | 0.95 | ||||||

| Change 0-6 months | 0.89-1.0 | 0.95 | 0.05* | |||||||||

| Change 6-12 months | 0.91-1.06 | 0.91-1.03 | 0.97 | 0.32 | 0.96 | 0.32 | ||||||

| SAI—E score | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 0.94-1.13 | 0.90-1.09 | 0.90-1.09 | 1.03 | 0.59 | 0.99 | 0.85 | |||||

| Change 0-6 months | 1.04-1.23 | 1.13 | 0.006* | |||||||||

| Change 0-12 months | 0.96-1.09 | 0.96-1.09 | 0.84 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 0.42 | ||||||

Components of insight

We did not have sufficient statistical power to examine separately specific components of insight or symptom clusters. Nevertheless, exploratory analyses using GAF as the outcome measure indicated that at 6 months (model 2) the illness awareness dimension of the SAI–E was a significant predictor (F = 21.6, P<0.001; adjusted R 2 = 0.330). Significant effects also emerged in model 3 with the illness awareness (F = 7.96, P = 0.006) and treatment compliance (F = 12.2, P = 0.001) dimensions (but not relabelling).

Discussion

Three major findings emerged from this study. The first was that improvement in level of insight into illness during the early part of the illness predicted good outcome, regardless of how it was defined, in patients with schizophrenia. This is in spite of the fact that such improvement continued over the subsequent 6 months, whereas psychopathologic symptoms tended to plateau over this period (Fig. 1). This was shown in regression models which took into account other factors including psychopathology. In England, Drake et al examined a sample of patients with first-episode non-affective psychosis recruited for a trial of cognitive–behavioural therapy and observed poor insight (assessed with a self-report insight scale) to be an independent predictor of relapse and readmission. Reference Drake, Dunn, Tarrier, Bentall, Haddock and Lewis10 This confirmed earlier work in studies using mostly cross-sectional designs and prevalent cases, Reference Sanz, Constable, Lopez-Ibor, Kemp and David14,Reference McEvoy, Applebaum, Apperson, Geller and Freter20–Reference Cuesta, Peralta and Zarzuela27 plus prospective studies. Reference David, van Os, Jones, Harvey, Foerster and Fahy8,Reference Gharabawi, Lasser, Bossie, Zhu and Amador28–Reference Ceskova, Prikryl, Kasparek and Kucerova30 Gharabawi et al carried out secondary analyses on an open-label multicentre trial of long-acting risperidone injection, and found that change on the insight item from the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia correlated with change in Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI–S) scores at 1 year, but not with quality of life. Reference Gharabawi, Lasser, Bossie, Zhu and Amador28 Saeedi et al reported on 278 patients admitted to a Canadian early psychosis service. Reference Saeedi, Addington and Addington29 The group was dichotomised on the basis of the PANSS insight score. Over 3 years those with persistently poor insight had persistently more symptoms and cognitive impairment.

In our study, insight at baseline did not predict remission without relapse or global functioning, but participants whose insight improved relatively early on in treatment had the better outcomes. The same pattern emerged for improvement in psychopathology: baseline scores failed to predict outcome, whereas improvement over the first 6 months did. Later improvement (6–12 months) in insight and psychopathology did not predict outcome even though it was more proximal to it. In Ireland, Crumlish et al reported that early improvement in insight on a self-report scale predicted suicidal behaviour when assessed at 4 years. Reference Crumlish, Whitty, Kamali, Clarke, Browne and McTigue31 We await report of whether insight predicted better general outcome in this sample.

Quality of outcome

Our second finding was that during the follow-up period remission was common and relapses rare. Almost half of the patients had full remission of symptoms over the course of the 12-month follow-up. This rate of remission (50%) is midway between rates reported from urban and rural Chandigarh as part of the DOSMeD project but lower than the 69% recorded in Vellore in SOFACOS in the early 1980s. 16–Reference Jablensky, Sartorius, Emberg, Anker, Korten and Cooper18 This is consistent with the ‘favourable outcome’ hypothesis in low- and middle-income countries, Reference Jablensky, Sartorius, Emberg, Anker, Korten and Cooper18,Reference Lin and Kleinman32–Reference Hooper, Harrison, Janca and Sartorius35 but see Cohen et al Reference Cohen, Patel, Thara and Gureje36 and Leff Reference Leff37 for a debate on this question.

Duration of untreated psychosis

Our third finding is the significant association between DUP and both outcome measures, even after changes in insight and psychopathology were controlled for (see Drake et al). Reference Drake, Haley, Akhtar and Lewis38 Patients with longer DUP were less likely to achieve full remission. This is in line with many published studies in various settings including low- and middle-income countries. Reference Marshall, Lewis, Lockwood, Drake, Jones and Croudace39–Reference Farooq, Large, Nielssen and Waheed41 In our study the good outcome and poor outcome groups had a mean DUP of 67.1 weeks and 122.5 weeks respectively. It is not certain that reducing this period would necessarily improve outcome, but this is surely a worthwhile issue for research and clinical development. We did not find any gender effects on outcome in this study. Superior outcome in women was noted both in DOSMeD and other studies from India and in rural China, although not in Nigeria or Colombia. Reference Hooper, Harrison, Janca and Sartorius35,Reference Ran, Xiang, Huang and Shan40,Reference Thara and Rajkumar42–Reference Ohaeri44

Insight, psychopathology and culture

We found fairly consistent associations between insight and psychopathology. Our baseline findings using the expanded BPRS and SAI–E showed weak but significant inverse correlations between total BPRS score and the relabelling dimension. Reference Saravanan, Jacob, Johnson, Prince, Bhugra and David5,Reference Drake, Pickles, Bentall, Kinderman, Haddock and Tarrier45 However, at follow-up all three dimensions of insight (awareness, compliance and relabelling) and total insight scores showed predictably significant although weak relationships with psychopathology. This is in line with most studies in a variety of settings, including India, Reference David, Amador and David6,Reference Saeedi, Addington and Addington29,Reference Kulhara, Chakrabarti and Basu46–Reference Mintz, Dobson and Romney48 but see Drake et al who found that paranoia and delusions specifically were unrelated to global insight. Reference Drake, Pickles, Bentall, Kinderman, Haddock and Tarrier45 Studies in our cohort using quantitative and qualitative methods suggest that early change in insight or remaining within the existing ‘collaborative social world’ may have benefits. Reference Saravanan, Jacob, Deepak, Bhugra, Prince and David19 One clinical implication is that efforts to improve insight taking account of local cultural factors could yield benefits in outcomes and might relate to the supposedly superior prognosis of psychosis in settings such as those in south India.

Methodological issues

The participants in this study were located in a mental health service centred on a large hospital. This may represent a selection bias. However, this is likely to have resulted in a more severely affected patient cohort than one derived from community-based case ascertainment. Initially, 29% had to be excluded, mostly owing to florid psychotic disturbance rendering formal assessment impossible. Withdrawal rates were low, reflecting in large part the influence of intact family structures which support patients and value medical treatment. Outcome was categorised relatively crudely to assist comparison with other studies, yet the continuous and categorical outcomes yielded highly consistent findings. The clinically defined categorical outcome was made in part by the psychiatric researcher (B.S.), who also participated in the initial and follow-up ratings of psychopathology (including insight) and measurement of DUP, so may have been biased. However, the research nurse (S.J.) who rated GAF outcome was unaware of DUP status. This method ensured that at least one of the outcome measures is unlikely to have been biased by knowledge of DUP or other baseline factors. Again, the consistency in the findings regarding predictors of outcome provides reassurance that such observer bias was minimal. Finally, we were unable to measure the extent to which aspects of culture shape insight and hence outcome of schizophrenia in this study in the absence of contemporaneous control data from other countries or settings.

Funding

B.S. was supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust. (Ref. no. 064699).

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and support staff of Christian Medical College, Vellore, for their cooperation and commitment to completion of the study.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.