Sexual dysfunction is common in people with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, with reported prevalence rates of 30–80% in women and 45–80% in men. Reference Montejo, Majadas, Rico-Villademoros, Llorca, De La Gándara and Franco1–Reference Baggaley6 It is known to affect all domains of sexual function, Reference Smith, O'Keane and Murray5,Reference Raja and Azzoni7 including desire, arousal, erection, ejaculation and orgasm; and despite being known to be a major cause of poor quality of life and non-adherence to medication, Reference Montejo, Majadas, Rico-Villademoros, Llorca, De La Gándara and Franco1,Reference Rosenberg, Bleiberg, Koscis and Gross8,Reference Olfson, Uttaro, Carson and Tafesse9 it is generally underestimated, often neglected and poorly managed. Reference Dossenbach, Hodge, Anders, Molnár, Peciukaitiene and Krupka-Matuszczyk2,Reference Ucok, Incesu, Aker and Erkoc10 So far, sexual dysfunction has been largely attributed to the deleterious effect of antipsychotic medication, Reference Cutler11,Reference Westheide, Cohen, Bender, Cooper-Mahkorn, Erfurth and Gastpar12 although recent data suggest that it may be a consequence of the disease itself and may also be related to symptom severity. Reference Howes, Wheeler, Pilowsky, Landau, Murray and Smith4,Reference Malik, Kemmler, Hummer, Riecher-Roessler, Kahn and Fleischhacker13 We predicted that if sexual dysfunction were an intrinsic function of psychotic disorders it would be evident in people with prodromal symptoms before the full development of frank illness and before the start of treatment with antipsychotic medication. To test this hypothesis we assessed the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in individuals at ultra-high risk of psychosis, and compared this with prevalence rates in patients with first-episode psychosis and a healthy control group. We also examined the association between sexual function and symptoms.

Method

Sample

Ultra-high risk group

Thirty-one individuals (mean age 26.8 years, s.d. = 6.88, 62% male) were recruited from Outreach and Support in South London, a clinical service for young people at high risk of developing psychosis. Reference Broome, Woolley, Johns, Valmaggia, Tabraham and Gafoor14 Participants were assessed using the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS), Reference Yung, Yuen, McGorry, Phillips, Kelly and Dell'Olio15 and the diagnoses were confirmed at a consensus meeting of the clinical team. To be included in the study, participants needed to meet the CAARMS criteria for attenuated positive psychotic symptoms, indicating that they were at ultra-high risk of psychosis. Reference Yung, Nelson, Stanford, Simmons, Cosgrave and Killackey16 None of the individuals in this ultra-high risk (UHR) group had received antipsychotic treatment at the time of assessment. All received regular clinical monitoring for at least 2 years to determine their subsequent clinical outcome: 6 persons in this group subsequently developed a psychotic disorder meeting ICD-10 criteria within the follow-up period (UHR transition subgroup) and 25 did not (non-transition subgroup). 17

First-episode psychosis group

We recruited 37 patients with a first episode of psychosis (mean age 28.5 years, s.d. = 7.33, 60% male) from the South London and Maudsley National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust, as part of the Improving Physical Health and Reducing Substance Use in Severe Mental Illness and the Genetic and Psychosis studies. All patients aged 18–65 years who met ICD-10 criteria for a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder (codes F20-F29 and F30-F33) were invited to participate in the study. The clinical diagnosis was obtained by administering the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN). Reference Wing, Babor, Brugha, Burke, Cooper and Giel18 Most people in this group were taking atypical antipsychotics (n = 29), except for 3 who were taking typical antipsychotics (haloperidol n = 2, trifluoperazine n = 1) and 5 who were medication-naive. Among the patients taking medication, 13 were taking antipsychotics known to be relatively sparing of prolactin (ziprasidone, aripiprazole, quetiapine, olanzapine and clozapine), whereas 19 were taking antipsychotics with a propensity to elevate prolactin (all the remaining antipsychotics). For classification of prolactin-raising/sparing antipsychotics, see The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines. Reference Taylor, Paton and Kapur19 Among those prescribed antipsychotics, the mean duration of treatment was 33.7 days (s.d. = 4.8, range 0–122) and the mean daily dose, expressed as chlorpromazine equivalents, was 322.9 mg (s.d. = 114.2). Reference Woods20

Control group

We recruited 56 healthy individuals (mean age 27.6 years, s.d. = 4.64, 50% male) from the same geographical area served by the mental health trust, by advertisement and from local general practice clinics. They were matched to the other samples on the basis of gender, age and estimated premorbid IQ score (1 s.d.).

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria for all participants were any history of a medical or physiological cause of gonadal or sexual dysfunction (including hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus or other endocrine or metabolic disorder, vascular disorders and neurological disorders), history of head trauma or injury, history of serious medical or surgical illness, intellectual disability, history of current or past organic psychosis or substance dependence, and being a non-native English speaker. Additional exclusion criteria for the control group were current psychiatric disorder, history of psychiatric illness and family history of any psychiatric disorder as assessed by an experienced psychiatrist in a detailed clinical interview.

Ethical approval was obtained from the hospitals and the Institute of Psychiatry research ethics committees. All participants came from the same London catchment area served by the Maudsley and King's College hospitals and gave written informed consent to participate in the study and for publication of data from the study.

Assessment

All participants completed the Sexual Function Questionnaire (SFQ), a structured self-report instrument that has been validated and specifically constructed to assess sexual function in patients with mental illness, including those with psychotic disorders. Reference Smith, O'Keane and Murray5 It contains 30 questions in total, requiring ‘true or false’ answers, and assesses sexual function over the past month. It does not assess changes following specific factors such as medication. The questionnaire includes subscales assessing libido, physical arousal, erectile function, masturbation, orgasm and ejaculation, and assesses the frequency and quality of function in each of these domains. Reference Smith, O'Keane and Murray5 It was designed so that the assessment of sexual function is not biased by whether the respondent has a sexual partner or not. Higher scores indicate greater impairment and a total SFQ score of 8 or above is the cut-off indicating sexual dysfunction. Psychotic symptoms were evaluated at the time of this assessment using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler21 The PANSS is a 30-item scale developed in order to provide a well-defined instrument to specifically assess both positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia as well as general psychopathology. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Calgary Depression Scale, Reference Addington, Addington, Maticka-Tyndale and Joyce22 which has been specifically validated to assess the level of depression in schizophrenia. Premorbid IQ was estimated using the New Adult Reading Test. Reference Nelson and O'Connell23

Statistical analysis

A power calculation was conducted using the effect size for the SFQ difference between patients with chronic psychosis and a control group from our previous study. Reference Howes, Wheeler, Pilowsky, Landau, Murray and Smith4 This indicated that a minimum group size of 10 was needed to detect a difference with 80% power at α = 0.05. Results were analysed using SPSS version 17.0 for Mac. Demographic variables were analysed using analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for non-parametric variables and bivariate correlations. We compared sexual function (SFQ total and subscale scores) between the UHR, first-episode psychosis and control groups using one-way analysis of covariance, controlling for age, as it is recognised that sexual function declines with age. Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) tests were used for post hoc analysis of differences between groups. An exploratory analysis was conducted using Student's independent t-tests to determine whether there was a difference in SFQ scores between the UHR transition and non-transition subgroups, between the non-transition subgroup and the control group, and between the transition subgroup and the first-episode psychosis group. Linear regression was used to test the hypothesis that sexual function was related to psychopathologic disorder, using SFQ total score and SFQ cut-off score as the dependent variables and positive, negative and general symptoms as independent variables. There is an established link between depressive symptoms and poor sexual function. Reference Clayton24 Because of this, where there was a significant relationship, the analysis was repeated including depressive symptom score (Calgary Depression Scale) as a covariate to determine whether the relationship were independent of depressive symptoms.

Results

Data on 124 participants who met the inclusion criteria were analysed. Table 1 reports the demographic and clinical measures for each group. Age (F (2,1290) = 0.673, P = 0.512) and gender (χ(2) = 1.2, P = 0.547) were not significantly different between groups. There was, as expected, a significant effect of group on PANSS and Calgary Depression Scale scores (Table 1).

Sexual function scores

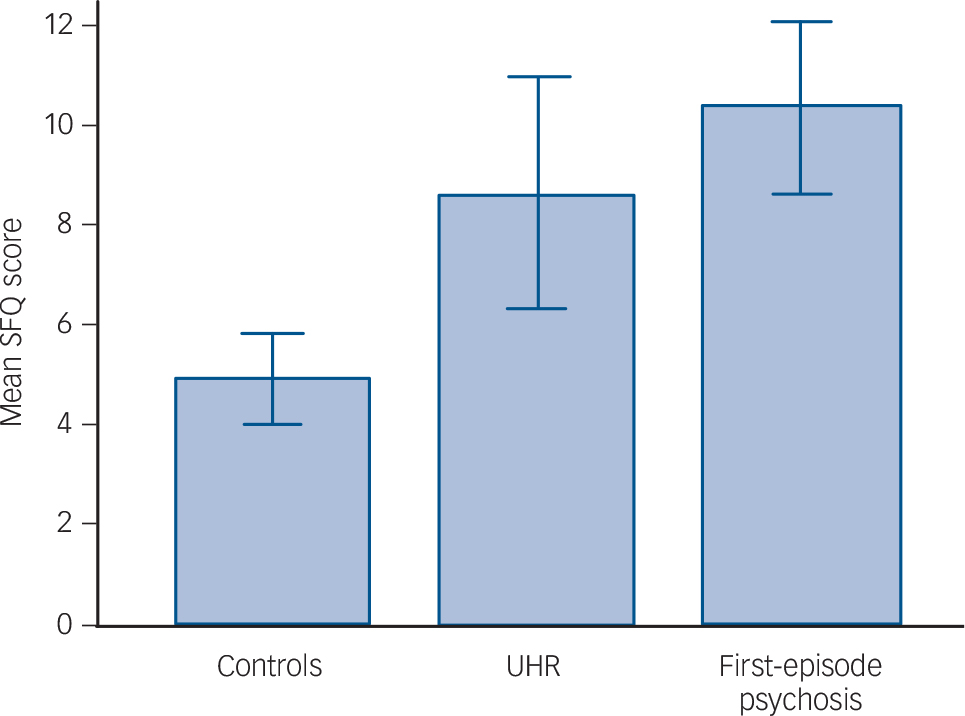

Figure 1 shows the mean total sexual dysfunction scores for each group. There was a significant effect of diagnostic group on sexual functioning (F = 13.36, d.f. = 3, P<0.001) with age as a covariate. There was no main effect of gender (F = 1,21, d.f. = 2,122, P = 0.274) and no interaction between gender and diagnostic group (F = 2,33, d.f. = 1,122, P = 0.102).

Using the SFQ cut-off for sexual dysfunction, 50% of the UHR group showed at least one type of clinical sexual dysfunction, compared with 65% of the first-episode psychosis group and 21% of the control group (Fig. 1). Table 2 lists the mean scores in each area of sexual function according to diagnosis, indicating that there was a significant effect of diagnostic group across several domains of sexual function. When the UHR group was compared with the control group there were significant differences between them in total SFQ score (P=0.001) and across all domains of sexual function, except for ejaculatory dysfunction (P = 0.764), vaginal responsiveness (P = 0.162) and masturbation (P = 0.616). There was no significant difference in total SFQ or domain scores between the UHR and first-episode psychosis groups (all P>0.1), apart from scores on masturbation (P = 0.02) where the first-episode psychosis group had significantly higher scores than the UHR group.

The UHR group members who made the transition to psychosis had a significantly higher total score on the SFQ (mean

TABLE 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample

| UHR group (n = 31) | First-episode psychosis group (n = 37) | Control group (n = 56) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d) | ||||

| Male | 25 (4.2) | 28.7 (6.5) | 28 (4.23) | t = 1.85, d.f. = 2, P = 0.165 |

| Female | 28.2 (9.6) | 28.2 (8.5) | 27.3 (5.0) | t = 0.104, d.f. = 2, P = 0.902 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 19 (62) | 22 (60) | 28 (50) | χ2 = 1.21, d.f. = 2, P = 0.547 |

| Female | 12 (38) | 15 (40) | 28 (50) | |

| Symptom scores, mean (s.d.) | ||||

| PANSS total score | 50.9 (20.8) | 61.2 (14.8) | 30.8 (1.8) | 65.2, d.f. = 3, P < 0.001 |

| CDS total score | 2.2 (3.0) | 3.9 (4.2) | 1.1 (0.3) | 7.84, d.f. = 2, P < 0.001 |

CDS, Calgary Depression Scale; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; UHR, ultra-high risk.

Fig 1 Sexual Function Questionnaire (SFQ) scores in the three diagnostic groups.

Higher values indicate poorer sexual function; error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. UHR, ultra-high risk.

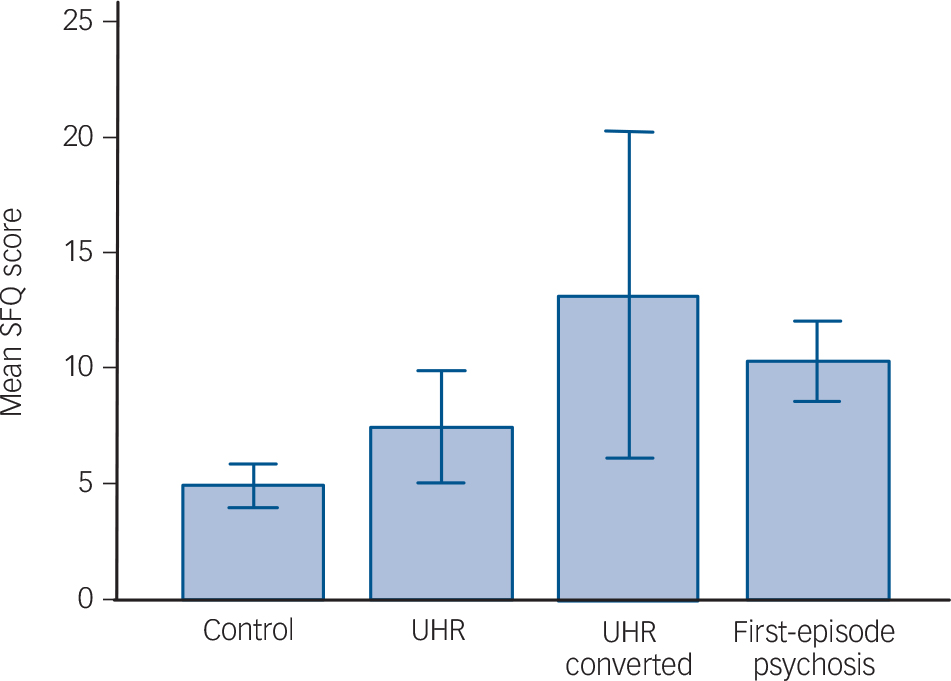

total score 13.16, s.d. = 6.70) compared with those who did not (mean total score 7.5, s.d. = 5.70; t(28) = –2.1, P = 0.028), indicating poorer sexual functioning in the transition subgroup (Fig. 2). Using the SFQ cut-off for sexual dysfunction, 83% of the UHR transition subgroup showed sexual dysfunction in one or more domains compared with 42% in the non-transition subgroup. Nevertheless, the SFQ total score was significantly higher in the non-transition subgroup than in the control group (t(61) = –2.1, P = 0.044). There was no significant difference

TABLE 2 Sexual Function Questionnaire subdomain scores

| Mean Sexual Function Questionnaire score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UHR group (n = 31) | First-episode psychosis group (n = 37) | Control group (n = 56) | d.f. | F | P | |

| Reduced libido | 1.32 a | 1.94 b | 0.55 | 3; 120 | 13.61 | <0.0001 |

| Arousal problems | 1.35 a | 1.61 b | 0.62 | 3; 120 | 5.88 | 0.001 |

| Erectile dysfunction | 1.36 a | 1.18 b | 0.57 | 3; 65 | 1.68 | 0.178 |

| Ejaculatory dysfunction | 0.85 a | 0.85 b | 1.07 | 3; 65 | 0.25 | 0.858 |

| Vaginal responsiveness | 2.27 | 1.60 | 1.39 | 3; 50 | 1.9 | 0.134 |

| Orgasmic dysfunction | 1.93 a | 2.02 b | 0.66 | 3; 119 | 8.79 | <0.0001 |

| Masturbation | 1.76 | 2.73 b,c | 1.50 | 3; 119 | 15.30 | <0.0001 |

UHR, ultra-high risk.

a Significant difference between UHR and control groups (P < 0.05, adjusted for multiple comparisons using Tukey's test).

b Significant difference between first-episode psychosis and control groups (P < 0.05).

c Significant difference between first-episode psychosis and UHR groups (P < 0.05).

Fig 2 Sexual Function Questionnaire (SFQ) scores in the different diagnostic groups, with the group at ultra-high risk (UHR) of psychosis divided into those who made the transition to psychosis (UHR converted) and those who did not (UHR).

Higher values indicate poorer sexual function; error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

in total SFQ score between the transition subgroup and the first-episode psychosis group (t(41) = 1.2, P = 0.237).

Relationship between sexual function, psychopathology and medication

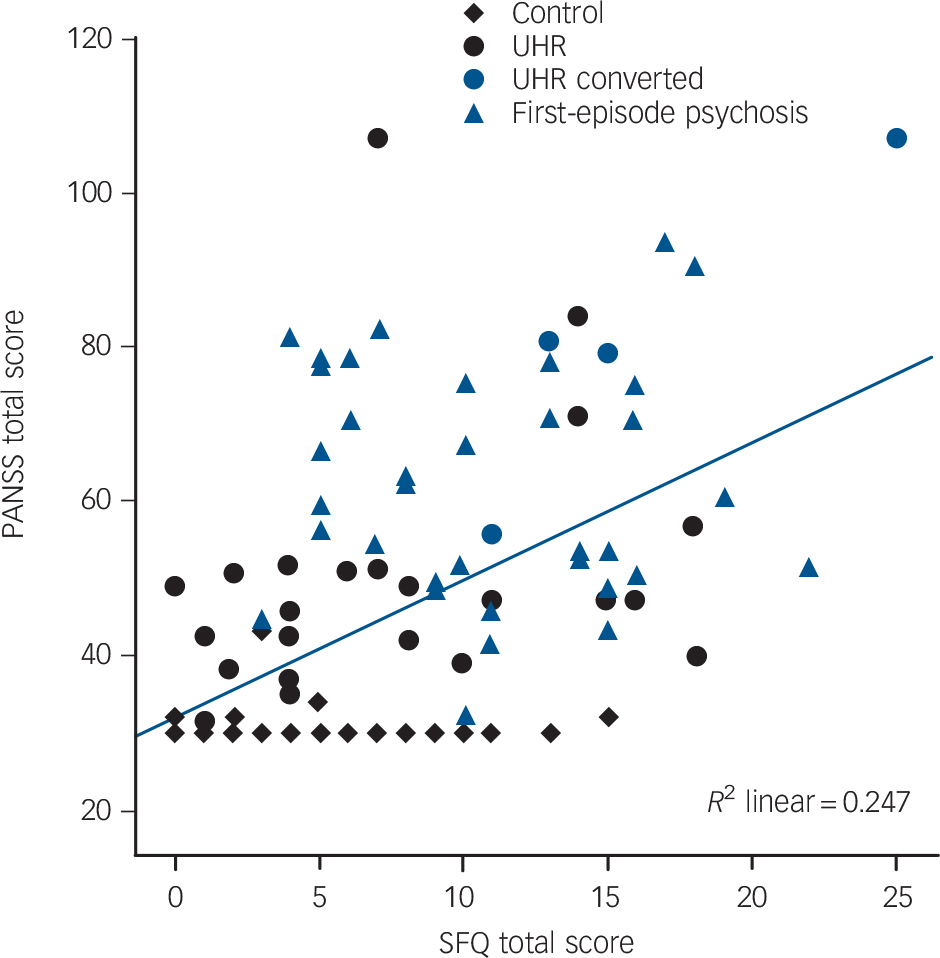

Figure 3 shows the results of a linear regression analysis testing the hypothesis that sexual function is associated with symptom severity. There was a significant positive relationship for the

Fig 3 Linear regression showing a relation between Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) and Sexual Function Questionnaire (SFQ) scores.

Diagonal line is fit line for total. There was a positive association between symptom severity and SFQ score (r(62) = 0.318, P = 0.004) which remained after adjusting for depressive symptoms (R Reference Dossenbach, Hodge, Anders, Molnár, Peciukaitiene and Krupka-Matuszczyk2 linear 0.247). UHR, ultra-high risk.

clinical sample between total PANSS scores and total SFQ scores (r(62) = 0.497, P<0.001), indicating that the more severe the symptoms, the worse the sexual function. Controlling for depressive symptoms, the strength of the association between total PANSS and SFQ scores was weakened but still remained highly significant (r(62) = 0.318, P= 0.004), indicating that greater symptom severity was associated with poorer sexual functioning independent of the presence of depressive symptoms. Finally, when data from the subsample of antipsychotic-naive patients were analysed independently, the relationship between severity of sexual dysfunction and severity of illness remained (r(5) = 0.305, P = 0.003).

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study to assess sexual function in individuals at ultra-high risk of psychosis. Our results show that sexual function is impaired prior to the onset of the first psychotic episode, with half of these individuals showing evidence of sexual dysfunction. These high rates of dysfunction are not specific to particular domains of sexual function, affecting sexual interest (libido) and arousal as well as erectile functioning and orgasm. The observed impairment was significantly greater than in healthy individuals, and similar to that found in the first-episode psychosis group, across most of the domains of sexual function. Furthermore, greater symptom severity in this group was associated with greater impairment in sexual function. We did not find an effect of gender or interaction between gender and diagnostic group on total sexual function, indicating that there was no difference between men and women in either diagnostic group in the degree to which their sexual function was impaired.

Early dysfunction

Previous studies have shown that sexual dysfunction is already present at illness onset, Reference Bitter, Basson and Dossenbach25,Reference Van Bruggen, van Amelsvoort, Wouters, Dingemans, de Haan and Linszen26 and in antipsychotic-naive patients, Reference Aizenberg, Zemishlany, Dorfman-Etrog and Weizman27 and a positive relationship between the severity of the illness and the severity of sexual dysfunction has also been found. Reference Malik, Kemmler, Hummer, Riecher-Roessler, Kahn and Fleischhacker13,Reference Uçok, Incesu, Aker and Erkoç28,Reference Fan, Henderson, Chiang, Briggs, Freudenreich and Evins29 Our study confirms and extends these findings, showing for the first time that sexual dysfunction is present in individuals at ultra-high risk of psychosis, even prior to disease onset and in the absence of antipsychotic medication. The positive linear relationship between symptom severity and total SFQ score after adjusting for depressive symptoms is further support for a link between developing illness and sexual dysfunction in psychosis. Our results thus extend previous findings and suggest that sexual dysfunction is a feature of vulnerability to or development of a psychotic illness, rather than due to antipsychotic medication or other treatment factors. One might argue that the observed relationship could be an epiphenomenon of antipsychotic treatment, as higher doses of antipsychotic medication could be associated with more severe illness. However, our analysis showed that the positive linear relationship between symptom severity and total SFQ score was also present in patients who were antipsychotic-naive, suggesting that the reported finding was not an effect of antipsychotic treatment.

Other factors

The importance of depressive symptoms in the aetiology of sexual dysfunction in psychotic disorders has been controversial, with some studies pointing towards a direct effect of depressive symptoms on sexual function, Reference Cohen, Kühn, Bender, Erfurth, Gastpar and Murafi30 and others finding no association between these variables. Reference Howes, Wheeler, Pilowsky, Landau, Murray and Smith4,Reference Fan, Henderson, Chiang, Briggs, Freudenreich and Evins29 Our data indicate that although depressive symptoms contribute to sexual dysfunction they do not fully explain all the sexual impairment seen in people with a psychotic disorder, and suggest that a component of sexual dysfunction is linked to the psychotic symptoms. The link between symptoms and sexual dysfunction suggests that they are mediated by the same underlying neurobiological factors. One potential candidate is dopaminergic dysfunction, which is already present at the ultra-high-risk stage, but appears to progress with the later onset of psychosis, Reference Howes, Montgomery, Asselin, Murray, Valli and Tabraham31,Reference Howes, Bose, Turkheimer, Valli, Egerton and Stahl32 and may disrupt motivational processing and arousal pathways required for sexual function. Reference Argiolas and Melis33

We did not find any difference in sexual function between patients taking relatively prolactin-raising and relatively prolactin-sparing antipsychotics. Although this finding is in line with some studies, Reference Howes, Wheeler, Pilowsky, Landau, Murray and Smith4 it contrasts with others. Reference Malik, Kemmler, Hummer, Riecher-Roessler, Kahn and Fleischhacker13,Reference Knegtering, van den Bosch, Castelein, Bruggeman, Sytema and van Os34 This finding should be interpreted cautiously because the sample size was small and does not preclude other side-effects due to prolactin elevation. Reference Wieck and Haddad35–Reference Howes, Smith, Gaughran, Amiel, Murray and Pilowsky37

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, we did not assess hormonal levels, making it impossible to analyse the association between sexual function and sex hormones or prolactin. Although several studies have reported associations between these factors, our study focused on the sexual functioning in a non-medicated group in whom we expected prolactin levels to be normal. Second, the size of the UHR subgroup who subsequently developed a psychotic disorder was small. Third, we were unable to examine subdomains of sexual function owing to power limitations, and so further studies are needed to determine whether there are differences in particular domains of sexual function according to gender and diagnostic group. Fourth, most of the participants in the first-episode psychosis group were taking antipsychotic drugs. Such drugs may impair sexual dysfunction through direct and indirect mechanisms, including the effect of higher prolactin levels on gonadal hormone levels, and other mechanisms such as alpha-2-adrenergic blockade. However, antipsychotic treatment might also improve some aspects of sexual functioning, by reducing positive and negative symptoms and thus improving libido, for example. Although we cannot exclude an antipsychotic effect on sexual function in the first-episode psychosis group, this was not a factor in the UHR group because none of them were receiving antipsychotic treatment. Moreover, the duration of treatment in the first-episode psychosis group was brief and the doses involved were low. Finally, although the similar profiles of sexual dysfunction in the two patient groups suggest a common underlying factor, it is possible that different factors underlie the sexual dysfunction in each group. Antipsychotic drug treatment in the first-episode psychosis group could (by treating the psychosis) improve aspects of sexual function, but at the same time lead to treatment-emergent sexual side-effects possibly due to monoaminergic, adrenergic or muscarinic actions. A prospective study is needed to evaluate this.

In summary, impaired sexual function is evident prior to the first episode of psychosis in people who are yet to receive antipsychotic medication and in a similar degree to that seen in people with a first psychotic episode, and is also related to the severity of psychotic symptoms.

Funding

The Improving Physical Health and Reducing Substance Use in Severe Mental Illness study is funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR). This paper presents independent research commissioned by the NIHR under its Program Grants for Applied Research scheme (RP-PG-0606-1049).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.