Recovery is an approach that focuses on supporting people with mental health conditions to live as well as possible,Reference Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare Duke and Slade1 whether or not symptoms remain.Reference Slade, Amering, Farkas, Hamilton, O'Hagan and Panther2 Recovery-orientation has emerged as a global mental health priority for example in the World Health Organization Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020,3 and is national mental health policy in many countries such as the UK.4 Peer support workers (PSWs) are a visible manifestation of a recovery orientationReference Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams and Slade5,Reference Corrigan, Larson, Smelson and Andra6 involving people with lived experience of mental health problems helping others to recover from mental health conditions. PSW roles are being implemented internationally, and increasingly in lower-resource settings as a cost-effective approach to reduce the burden of mental health problems,Reference Camacho, Ntais, Jones, Riste, Morriss and Lobban7,Reference Sikander, Lazarus, Bangash, Fuhr, Weobong and Krishna8 to address the mental healthcare gap,Reference Pathare, Brazinova and Levav9,Reference Patel, Collins, Copeland, Kakuma, Katontoka and Lamichhane10 and as a form of ‘task-sharing’Reference Pathare, Brazinova and Levav9 to help support the service delivery of already strained and overwhelmed mental health systems. Overall, peer support has been identified as a central approach to recovery,Reference Roberts and Boardman11 and is endorsed by psychiatrists.Reference Gambino, Pavlo and Ross12

Some systematic reviews identify the limited evidence base relating to PSWs,Reference Lloyd-Evans, Mayo-Wilson, Harrison, Istead, Brown and Pilling13 but overall the weight of evidence indicates positive outcomes including empowerment,Reference Van Gestel-Timmermans, Brouwers, Van Assen and Van Nieuwenhuizen14 hope,Reference Schrank, Bird, Rudnick and Slade15,Reference Cook, Copeland, Jonikas, Hamilton, Razzano and Grey16 social relationships,Reference Lucchi, Chiaf, Placentino and Scarsato17,Reference Arbour and Rose18 self-efficacy,Reference Mahlke, Priebe, Heumann, Daubmann, Wegscheider and Bock19 recovery,Reference Chinman, Oberman, Hanusa, Cohen, Salyers and Twamley20 symptomatologyReference Rivera, Sullivan and Valenti21 and reduced readmissions to acute care.Reference Johnson, Lamb, Marston, Osborn, Mason and Henderson22 PSWs are an increasingly common member of the multidisciplinary clinical team, interacting with other professionals yet being asked to retain a ‘lived experience’ identity. For mental health professionals, this can create dilemmas in terms of relationships, issues of confidentiality, ethics, decision-making and role clarity.Reference Collins, Firth and Shakespeare23 In order to work effectively with PSWs, a clear understanding of the role and how it is modified in different clinical populations and settings is needed. The aim of this review was to characterise pre-planned modifications (that were planned or allowed for in the design of the intervention arising from decisions made before implementation) and unplanned modifications (made because of unforeseen changes to the intervention that occur after implementation) to mental health peer support work for adults with mental health problems. The objectives were to develop a typology of types of modifications, to characterise the rationales for these modifications, and to identify modifications made specifically in low- and middle-income settings.

Method

The protocol of this systematic review was developed in accordance with PRISMA guidelinesReference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman24 and registered on PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) on 24 July 2018: CRD42018094832.

Eligibility criteria

We included studies about PSWs supporting adults aged 18 years or older with a primary diagnosis of mental illness, and those that explicitly identified modifications including changes, variations or adaptations made before (‘pre-planned’) or while (‘unplanned’) implementing a PSW intervention. A modification could be identified in various ways, such as changes to the intervention manual or to the role of the PSW, and an inclusive approach to inclusion was used. We excluded studies that: did not explicitly refer to modifications; had fewer than three participants; and studies that reported on mutual aid, peer-run organisations, naturally occurring peer support, peer navigation interventions and peer support delivered exclusively online. No studies were excluded on the basis of comparators, control conditions, service setting or clinical diagnosis. Included study designs were randomised controlled trials, controlled before and after studies, cohort studies, case–control studies and qualitative studies. Studies were included if reported in English, French, German, Hebrew, Luganda, Spanish or Swahili (chosen as languages in Using Peer Support In Developing Empowering Mental Health Services (UPSIDES) study sites), with a date of publication on or before July 2018.

Information sources

Six data sources were used: (a) electronic bibliographic databases (n = 11) searched were Medline (OVID), Embase (OVID), Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (EBSCHO), PsycINFO (OVID), Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, OpenGrey, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I, African Journals OnLine, and Scientific Electronic Library Online; (b) table of contents (n = 9) of International Journal of Social Psychiatry, Social Psychiatry and Epidemiology, Psychiatric Services, Journal of Recovery in Mental Health, Journal of Mental Health, Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal and BJPsych International (chosen as publishers of PSW studies); (c) conference proceedings of European Network for Mental Health Service Evaluation (n = 12 conferences since 1994) and Refocus on Recovery (n = 4 conferences since 2010) (chosen as recovery-relevant academic conferences with available proceedings); (d) websites (n = 10): http://peersforprogress.org; https://together-uk.org; https://mentalhealth.org.uk; www.mind.org; www.mihinnovation.net; www.inaops.org; www.peerzone.info; https://cpr.bu.edu; https://peersupportcanada.ca; https://medicine.yale.edu/psychiatry/prch/ (chosen as they host PSW materials); (e) a preliminary list of included studies was sent to experts (n = 36) requesting additional eligible studies; (f) forward-citation tracking was performed on all included studies using Scopus and backward-citation tracking by hand-searching the reference lists of included studies.

Search strategy

The search strategy was adapted from a published systematic review concerning peer support for people based in statutory mental health services.Reference Pitt, Lowe, Hill, Prictor, Hetrick and Ryan25 The search strategy was modified for each database, and an example of the search strategy used for Medline is shown in supplementary data 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.264. All searches were conducted from database inception until July 2018.

Study selection

After removing duplicates, the titles and abstracts of all identified citations were screened for relevance against the inclusion criteria by D.T., with a randomly selected 5% sample independently assessed by R.N. Concordance between the two reviewers was 91%. Full texts were single-screened by D.T. and R.N. then independently extracted data from 55% of included publications, so a randomly selected 10% were independently extracted by both researchers, who discussed their data extraction to check for adequate agreement.

Data abstraction

For each included publication, information was extracted on (a) study characteristics including study design, study participant inclusion and exclusion criteria, and sample size; (b) mode of intervention delivery; (c) where the intervention was performed including country, and service setting; and (d) pre-planned and unplanned modifications made to the peer support work, and the rationale for planned and unplanned modifications. The data abstraction table is shown in supplementary data 2.

Quality assessment

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) was used to assess the quality of eligible studies. CASP checklists do not provide an overall scoring, so a scoring system used in a previous systematic reviewReference Matthews, Ellis, Furness and Hing26 was applied. Each CASP item rated ‘yes’ scored 1 point and each item rated ‘no’ scored 0 points. The percentage score for the 10-item CASP randomised controlled trial checklist, the 10-item CASP qualitative checklist, the 12-item CASP cohort checklist and the 11-item CASP case control checklist was calculated, with studies scoring ≥60% graded as good quality, studies scoring 45% to 59% graded as fair quality, and studies scoring below 45% graded as poor.Reference Kennelly, Handler, Kennelly and Peacock27,Reference Adhia, Bussey, Ribeiro, Tumilty and Milosavljevic28

Synthesis of results

A three-stage narrative synthesis was conducted on included papers,Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai and Rodgers29 modified in line with recent reviews.Reference Rennick-Egglestone, Morgan, Llewellyn-Beardsley, Ramsay, McGranahan and Gillard30,Reference Llewellyn-Beardsley, Rennick-Egglestone, Callard, Crawford, Farkas and Hui31 The four analysts (A.C., R.N., M.S. and D.T.) came from varied professional (nursing, psychology) and disciplinary (health services research, social science, psychotherapy) backgrounds. In stage 1 (developing a preliminary synthesis), modifications and rationales for modifications identified in included studies were synthesised. Findings were tabulated and an initial coding framework was developed, through thematic analysis, to group modifications that were pre-planned and unplanned, and rationales for both types of modification. Vote counting of number of papers identifying each theme was performed, the data were interpreted as providing an initial indication of strength and ordering of themes. This method could have been interpreted as providing an indication of themes more amenable to change rather than strength, however, for the purpose of this paper, vote counting was used to determine the strength of themes. A preliminary draft of the modifications and rationale for modifications was developed and refined by analysts. In stage 2 (comparison between studies), the relationships within and between studies were explored. Identified modifications and rationales were compared between higher-income versus lower-income countries and pre-planned versus unplanned modifications. In stage 3 (assessing the robustness of the synthesis), the findings from subgroup analysis of only good-quality studies was compared with the framework from all included studies.

Results

Included studies

The search identified 15 300 studies, from which 39 were included. The flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1 and the complete data abstraction table including all references is shown in supplementary data 2.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of the study selection process.

The 39 included studies were predominantly conducted in higher-income countries, comprising USA (n = 25), UK (n = 5), Canada (n = 4), Australia and USA (n = 1), Australia (n = 2) and Republic of Ireland (n = 1), with a single study conducted in an upper-middle income country (Libya). Designs comprised qualitative (n = 12), randomised controlled trial (n = 13), pre–post (n = 10), case–control (n = 3) and cohort (n = 1).

Stage 1 (developing a preliminary synthesis)

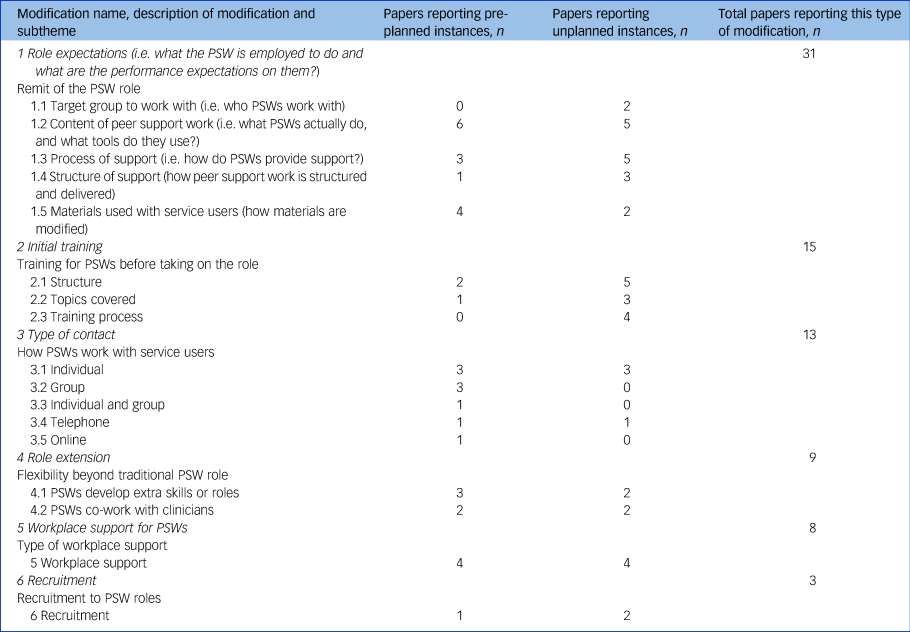

Six types of modifications to peer support work were identified, as shown in Table 1. The coded text including detailed examples from the included publications is shown in supplementary data 3.

Table 1 Types of modifications made to peer support work

PSW, peer support worker.

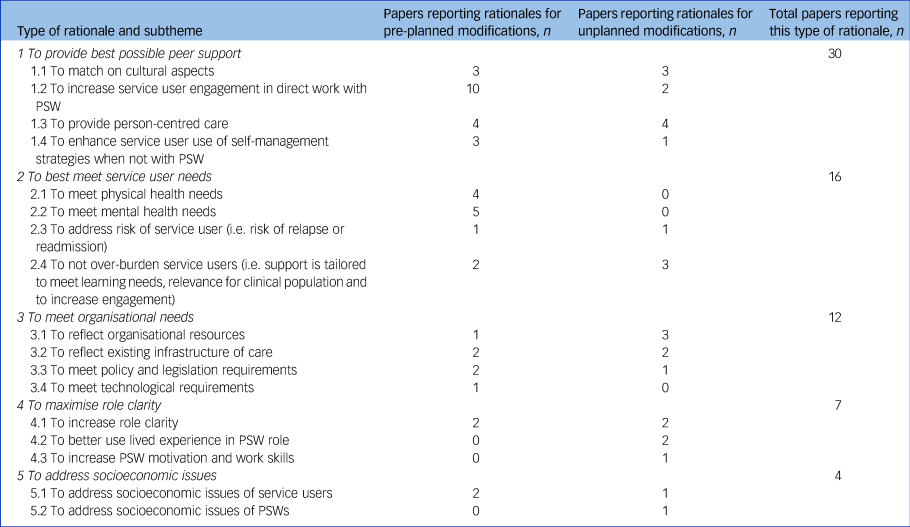

Five types of rationale for modifications to peer support work were identified, as shown in Table 2. The coded text including detailed examples from included publications is shown in supplementary data 4.

Table 2 Types of rationales for modifications made to peer support work

Stage 2 (comparison between studies)

Overall, 22 (56%) of 39 included studies reported only pre-planned modifications, 10 (26%) reported only unplanned modifications and 7 (18%) studies reported both pre-planned and unplanned modifications. Including only the 22 studies reporting pre-planned instances of modifications did not lead to deletion of any of the strongest themes. However, the ordering changed, with the four strongest themes being: role expectations; type of contact; role extension; and workplace support for PSWs. Including only the ten studies reporting unplanned modifications in the framework did not markedly change the ordering, with the three strongest themes being: role expectations; initial training; and role extension.

Across all included studies, 38 (97.4%) were conducted in high-income countries and 1 (2.6%) in a low-middle income country. Including only the 38 studies conducted in high-income countries did not change the strength or ordering of themes. Including the one study conducted in a low-middle income country led to the deletion of four themes: type of contact; role extension; workplace support for PSWs; and initial recruitment. The two strongest themes in the low-middle income study setting were: role expectations and initial training, with the subthemes of: materials used with service users; structure; and topics covered.

A total of 36 (92%) of the 39 included studies reported a rationale for modifications, comprising 22 (61.1%) providing rationales for planned modifications, 9 (25%) for unplanned modifications and 5 (13.8%) studies reporting rationales for both pre-planned and unplanned modifications. Including only the 22 studies reporting rationales for planned modifications in the framework did not lead to any changes to the ordering or deletion of any themes, with the three strongest themes being: to provide best possible peer support; to best meet service user needs; and to meet organisational needs.

Including only the nine studies reporting rationales for unplanned modifications, the ordering changed slightly, with to provide best possible peer support; to meet organisational needs; and to maximise role clarity emerging as the strongest themes. A total of 35 (97.2%) studies were conducted in high-income countries and 1 (2.8%) in a low- or middle-income country. Including only the 35 studies conducted in high-income countries did not change the order or strength of themes in the rationale framework. Including the one study conducted in a low-middle income country led to the deletion of three themes: to best meet service user needs; to maximise role clarity; and to address socioeconomic issues. The strongest themes were to provide best possible peer support and to meet organisational needs. The subthemes included: to match on cultural aspects; to enhance service use of self-management strategies when not with PSW; to meet organisational resources; and to meet infrastructure of care.

Stage 3 (assessing for the robustness of synthesis)

The quality rating of studies is shown in supplementary data 5. Studies were rated as good quality (n = 28), fair quality (n = 5) or poor quality (n = 6). Excluding the 11 studies rated as poor or fair quality did not greatly influence the content and strength-of-theme ordering for either modifications or rationales. The three strongest modification themes remained role expectations; initial training; and type of contact, with only workplace support for PSWs moving up in the order to joint third strongest theme. The order and strength of themes did not change markedly in the rationale framework, with to provide best possible peer support; to meet organisational needs; and to best meet service user needs being the strongest themes.

Discussion

This systematic review and narrative synthesis identified a typology of five rationales and six types of modifications to formal mental health peer support work when implemented in diverse settings. Insufficient evidence was available to identify types or rationales of modifications specific to lower-resource settings. There was no evidence of study quality having an impact on the findings, and most types of modification occurred both as planned and unplanned modifications.

Peer support is a complex intervention. Formal reporting of the intervention would support understanding of modifications. The Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) reporting guidelines identify how to report complex interventions to allow reliable implementation and replication.Reference Hoffman, Glasziou, Boutron, Milne, Perera and Moher32 Item 10 of the TIDieR checklist is ‘Modification: If the intervention was modified during the course of the study, describe the changes (what, why, when and how)’ – changes which in this review were called unplanned modifications. Earlier TIDieR items involve a complete description of the intervention, covering what in this review was called planned modifications. As none of the included studies used the TIDieR reporting guidelines, descriptions of modifications and their rationale were inconsistent, so underreporting of modifications is probable, which would lead to not all relevant PSW studies with modifications being included.

No study was designed to anticipate unplanned modifications. In trial methodology, an adaptive trial design involves pre-planned modification of trial procedures based on interim analysis during the conduct of the trial.Reference Chow and Chang33 This design is an approach to reducing resource use, decreasing time to trial completion and improving the likelihood that trial results will be scientifically or clinically relevant.Reference Thorlund, Haggstrom, Park and Mills34 A key feature of adaptive designs is that modifications are expected, and based on continuous learning as data accumulates during the trial. None of the included studies used an adaptive design, even though this is a relevant approach. For example, adaptive enrichment occurs when interim analysis shows that a treatment has more promising results in one subgroup of patients, in which case the eligibility criteria are modified to investigate the efficacy of the intervention in that subgroup.Reference Ning and Huang35 The identified unplanned adaptation of modifications to the target group could be more effectively managed by adopting an adaptive enrichment strategy.

The highest proportion of unplanned to pre-planned modifications occurred for the initial training modification. PSW training programmes have developed internationally in an uncoordinated way, including both accredited and non-accredited courses. Networks are emerging such as the International Association of Peer Specialists (www.inaops.org) and the Global Network of Peer Support (www.peersforprogress.org), but as yet there are no widely agreed consensus statements on the key non-modifiable and modifiable components of PSW initial training. Established approaches to differentiating between what can and cannot be modified could be followed.Reference Toney, Knight, Hamill, Taylor, Henderson and Crowther36

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this review include the multilanguage and systematic strategy used, and the robustness of methodology including multiple analysts and quality appraisal of studies. Several limitations of this review can be identified. First, the quality rating tool used in the synthesis excluded few studies, and resulted in minimal changes to the ordering of themes. Other critical appraisal tools could also be considered or used in combination with CASP in future studies to enhance robustness of evaluation. Second, the absence of established peer support brands made provenance and modifications difficult to establish, as has been found with other complex interventions.Reference Wallace, Bird, Leamy, Bacon, Le Boutillier and Janosik37 Developing named manualised approaches to implementing peer support would make it easier to identify when future studies are replicating versus adapting the approach. Third, meaningful comparisons between modifications made in higher- versus lower-income settings was not possible because only one non-high-income setting study was included. In addition, studies conducted in different global jurisdictions including the global south were not located or included. More searching of grey literature, modifications to the inclusion criteria and a broader expert consultation might have identified studies from lower-income settings and a wider range of countries, for example ChinaReference Fan, Ma, Ma, Xu, Lamberti and Caine38 and Uganda,Reference Hall, Baillie, Basangwa, Atukunda, White, Jain, Orr and Read39 or related studies such as the ReDeAmericas Program in Latin America (www.cugmhp.org/programs/redeamericas).

Implications

The review provides an evidence-based framework for systematic consideration of different types of candidate modification to peer support implementation. An appropriate approach would involve considering each rationale in turn, framed as a question, for example ‘What needs to be modified to provide best possible peer support in our setting?’ Where this process suggests that modification may be indicated, the modification types identified in relation to the rationale provide candidate changes to consider in relation to each question. This approach is likely to lead to a more systematic consideration of whether and how to modify the approach to peer support to different settings, especially when informed by an understanding of influences on implementation.Reference Ibrahim, Thompson, Nixdorf, Kalha, Mpango and Moran40

Identifying the wide range of modifications also has research implications. Evaluative research to identify the non-modifiable versus modifiable components is needed, to differentiate between desirable local adaptations versus non-desirable changes to the core components of peer support. Evaluations of peer support implementation identify that differing organisational cultures lead to differences in role expectations,Reference Ibrahim, Thompson, Nixdorf, Kalha, Mpango and Moran40 and issues of professionalism and practice boundaries are common.Reference Gillard, Edwards, Gibson, Owen and Wright41 Identifying when a modification is sufficiently large as to mean it is no longer a peer support role is an important future research focus. A second research priority is understanding when and where modifications are needed for implementation of peer support work, such as in work with asylum seekers and refugees,Reference Turrini, Purgato, Acarturk, Anttila, Au and Ballette42 and work in different types of clinical settings and populations. For example, service settings of hospital versus community and clinical population may be a focus for future research. The UPSIDES study is addressing the challenge of investigating how peer support work can be implemented in settings that differ in income levels, through implementation research and a randomised controlled trial in sites in Ulm (Germany), Hamburg (Germany), Kampala (Uganda), Dar es Salaam (Tanzania), Beer Sheva (Israel) and Pune (India). As interest in peer support work is growing internationally, evidence-based approaches to modifying the PSW role to meet local needs while retaining role integrity become essential.

Funding

UPSIDES received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No 779263. M.S. acknowledges the support of the Center for Mental Health and Substance Abuse, University of South-Eastern Norway and the NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre. This publication reflects only the authors’ views. The Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. The funding body had no role in the design of the study and in writing the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The study Using Peer Support In Developing Empowering Mental Health Services (UPSIDES) is a multicentre collaboration between the Department for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy II at Ulm University, Germany (B.P., coordinator); the Institute of Mental Health at University of Nottingham, UK (M.S.); the Department of Psychiatry at University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany (C.M.); Butabika National Referral Hospital, Uganda (David Basangwa); the Centre for Global Mental Health at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK (G.R.); Ifakara Health Institute, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania (D.S.); the Department of Social Work at Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, Israel (G.M.); and the Centre for Mental Health Law and Policy, Pune, India (J.K.).

Data availability

All collected data are included as supplementary information.

Author contributions

Conception and design of study: D.T., R.N. and M.S. Acquisition of data: A.C., D.T. and M.S. Analysis and/or interpretation of data for the work: A.C., D.T., R.N., G.R., D.S., J.K., G.M., R.H., C.M., B.P., J.R., M.S. and R.M. Drafting of the manuscript: A.C. and M.S. Revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: A.C., D.T., R.N., G.R., D.S., J.K., G.M., R.H., C.M., B.P., J.R., M.S. and R.M. Approval of the version of the manuscript to be published: A.C., D.T., R.N., G.R., D.S., J.K., G.M., R.H., C.M., B.P., J.R., M.S. and R.M. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work: A.C., D.T., R.N., G.R., D.S., J.K., G.M., R.H., C.M., B.P., J.R., M.S. and R.M.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.264.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.