Introduction

Contextualising LGBQ mental health

Increasing evidence suggests that sexual minorities, including those identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual or queer (LGBQ), are at significantly greater risk of experiencing a wide range of psychological difficulties including depression, anxiety disorders, suicidality, self-harm and substance misuse, compared with heterosexual communities (Plöderl and Tremblay, Reference Plöderl and Tremblay2015; Semlyen et al., Reference Semlyen, King, Varney and Hagger-Johnson2016). Minority stress theory proposes that chronic exposure to stigmatising and discriminatory social environments gives rise to unique stressors and stress processes that cause the excess rates of mental health problems amongst LGBQ communities (Hatzenbuehler, Reference Hatzenbuehler2009; Meyer, Reference Meyer2003). Minority stressors can be external or internal and include experiences of prejudice, discrimination, violence, anticipation and fear of rejection, decisions about when/whether to disclose or conceal one’s sexual orientation, negative internalised beliefs and feelings about one’s identity, and other well-meaning but unhelpful efforts to cope with the stress that stigma creates (e.g. substance misuse, risky sexual behaviour). It is proposed that over time, the effects of minority stressors aggregate and contribute to deleterious physical and mental health outcomes for sexual minority individuals.

LGBQ access to and outcomes from treatment

Whilst there is some preliminary evidence that LGBQ people may access mental health services disproportionately more than their heterosexual peers (Government Equalities Office, 2018), the evidence is at present limited. There is stronger evidence that members of the LGBQ community report feeling disconnected from and mistreated by health services when they do engage. Specifically, services may be perceived as discriminatory and as failing to address the specific needs of LGBQ people (Foy et al., Reference Foy, Morris, Fernandes and Rimes2019; Hudson-Sharp and Metcalf, Reference Hudson-Sharp and Metcalf2016; King et al., Reference King, Semlyen, Killaspy, Nazareth and Osborn2007). LGBQ individuals report that clinicians in health care settings often use heteronormative language which locates heterosexuality as the norm, and that many clinicians lack particular sensitivity to issues that sexual minority communities may face. Recently, some suggestions have been made to try and establish parity for LGBQ people accessing health services, including the routine monitoring of sexual orientation (in patients and practitioners) and mandatory LGBQ equality and diversity training (LGBT Foundation, 2017; NHS Digital, 2017).

However, despite attempts to reduce sexual orientation discrimination within the NHS, sexual minority groups are more likely to report adverse experiences with NHS primary care services than heterosexuals (Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Kanouse, Burkhart, Abel, Lyratzopolous, Beckett, Schuster and Roland2015). In England, Improving Access to Psychological Therapy (IAPT) services were initially set up in 2008 to increase access to evidence-based psychological interventions for adults experiencing mild to moderately severe common mental health problems, and are located in the English primary care health system. In their mixed methods survey study exploring LGBQ adults’ experiences of IAPT and primary care counselling services, Foy et al. (Reference Foy, Morris, Fernandes and Rimes2019) found that 41.9% of participants were concerned about experiencing stigma/discrimination in relation to their sexuality within psychological therapy services. This arguably hindered engagement with therapeutic interventions and may have deterred further help-seeking from mental health services. Indeed, qualitative data from this survey suggested that potential barriers for LGBQ people related to feared or experienced stigma in service delivery, reluctance to disclose sexuality, mismatched discussion of sexuality in treatment, and a lack of understanding and awareness of LGBQ identities and minority stressors.

There is also evidence of disparities in treatment outcomes for sexual minority adults receiving care from IAPT services in England. Rimes and colleagues (Rimes et al., Reference Rimes, Broadbent, Holden, Rahman, Hambrook, Hatch and Wingrove2018; Rimes et al., Reference Rimes, Ion, Wingrove and Carter2019) compared treatment outcomes for patients accessing talking therapies in IAPT services and reported that final therapy session symptom scores on measures of depression, anxiety and functional impairment were worse in lesbian and bisexual women than heterosexual women. Meanwhile, lesbian and bisexual women were also less likely to reliably recover from depression and anxiety compared with heterosexual women. A similar pattern has been reported for bisexual men.

A small body of evidence from the US is beginning to demonstrate that cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) interventions adapted specifically to meet the needs of sexual minorities are both acceptable and effective (Pachankis et al., Reference Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, Rendina, Safren and Parsons2015; Pachankis et al., Reference Pachankis, Clark, Burton, Hughto, Bränström and Keene2020; Ross et al., Reference Ross, Doctor, Dimito, Kuehl and Armstrong2007). Little is currently known, however, concerning how sexual minorities experience adapted, culturally sensitive, LGBQ-focused psychotherapeutic interventions (Israel et al., Reference Israel, Gorcheva, Burnes and Walther2008). According to Beck et al. (Reference Beck, Naz, Brooks and Jankowska2019) (p.11), culturally adapted therapies include those which: ‘…take an existing therapy as a starting point and then specifically adapts the language, values, metaphors and techniques of that approach for a particular community’. Within the context of LGBQ-focused psychotherapies, this includes adopting an LGBQ affirmative stance and adapting generic evidence-based CBT techniques, ideas and metaphors to encompass specific LGBQ references, and exploring the impact of minority stressors and internalised stigma on psychological wellbeing, for example.

The present study: evaluative aims and scope

Given the disparities in satisfaction and symptom improvement that exist between LGBQ and heterosexual populations accessing IAPT services, as well as the particular community-specific stressors that LGBQ populations face in relation to their mental health, and barriers in accessing mental health treatment (Foy et al., Reference Foy, Morris, Fernandes and Rimes2019), a novel CBT group intervention was developed specifically for LGBQ service users in a London-based IAPT service. The group aimed to offer a LGBQ affirmative space through which attendees could learn more about CBT principles as applied to overcoming stress, anxiety and depression, whilst also attempting to address how to cope with some of the specific minority stressors that this group are exposed to (e.g. internalised stigma, victimisation).

An initial pilot evaluation of this group suggests that participants who have completed it report significant reductions in symptoms of depression and anxiety, as well as improved functional impairment (Hambrook et al., in preparation). The current study used a qualitative online survey which was analysed to inductively explore how participants experienced the LGBQ Wellbeing Group. In particular, we were interested in aspects that participants experienced as helpful and unhelpful, and what changes attendees felt could improve the utility and experience of the group.

Method

Service setting

The setting for this evaluation was Talking Therapies Southwark (TTS), an IAPT service in South London. TTS is commissioned and funded by Southwark Care Commissioning Group (CCG) and operated by the South London & Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. TTS offers evidence-based psychological interventions, such as cognitive behavioural therapies (CBT), counselling for depression (CfD), dynamic interpersonal therapy (DIT) and others, for people aged 16 years and over experiencing common mental health problems, including depression and anxiety disorders. Like other IAPT services, TTS operates a ‘stepped care’ model; a system of delivering and monitoring treatments, so that the most effective yet least resource intensive treatment is delivered to patients first; only ‘stepping up’ to more intensive individual face-to-face therapies as clinically required. The service accepts both self- and GP referrals and the interventions offered include both individual and group therapies. Southwark is a borough in south London which has a highly diverse population. Office for National Statistics experimental research suggests that Southwark is the local authority area with the second highest sexual minority population in the UK, after Lambeth, at around 5% of the population (ONS, 2017).

The LGBQ Wellbeing Group

The LGBQ Wellbeing Group was developed by two clinical psychologists (D.H. and K.R.). The group was designed specifically for service users who identified as LGBQ and who were experiencing symptoms of depression, anxiety and/or stress. The aims of the group were to help teach CBT skills and tools for managing low mood, anxiety and stress in a group format, whilst also attempting to address some of the additional minority stress factors impacting the mental wellbeing of sexual minority populations (e.g. internalised stigma, discrimination, loneliness, identity concealment, etc.).

The group intervention was firmly based on group CBT principles and consisted of eight weekly 90-minute sessions, with each week focusing on a specific topic. The intervention was a closed group (an individual begins the intervention at the start of a new course and attends for all eight sessions). Topics covered within sessions included: introduction to CBT and the group; tackling avoidance; tackling negative and unhelpful thinking; tackling over-thinking and worry; coping with distressing feelings; negative beliefs about ourselves and self-criticism; developing body acceptance and confidence; loneliness and making connections; developing LGBQ confidence and resilience; and relapse prevention. The group was designed by two of the authors (K.R. and D.H.) who are both accredited therapists with the British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP). One of the authors (D.H.) co-facilitated every course from which these participants were recruited, with the other two authors (C.L. and K.R.), and other staff, co-facilitating different groups over time.

Each 90-minute session included a range of learning formats supported by a multi-media presentation, which served to provide an overall structure for the group session and the discussions that followed. Specific interventions included psychoeducation, group discussion, pair work and skills practice anchored around the session topics. Homework tasks were set each session to consolidate learning and encourage application of skills and ideas to patients’ daily lives.

Study design

A qualitative online survey design was utilised for this service evaluation project in order to provide initial exploratory qualitative evidence regarding participants experiences, in their own terms. According to Braun et al. (Reference Braun, Clarke, Boulton, Davey and McEvoy2020) (p. 3): ‘qualitative surveys offer one thing that is fairly unique within qualitative data collection methods – a “wide-angle lens” on the topic of interest that provides the potential to capture a diversity of perspectives, experiences, or sense-making’.

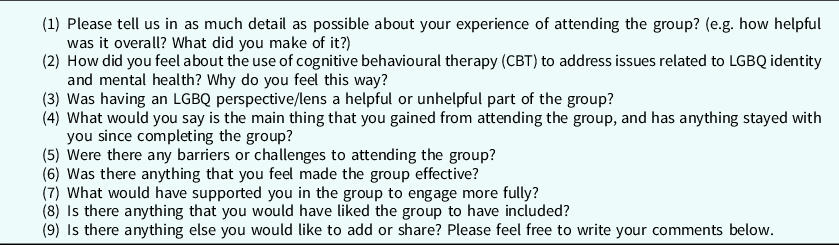

Accordingly, in the present study, an online qualitative survey was chosen over qualitative interviews, as it was felt that it would be more feasible for respondents to complete a survey in their own time. Furthermore, it was felt that a survey design would reduce the influence of social desirability effects upon participant response. A set of nine open-ended qualitative questions were devised (see Table 1), covering topics of: general experience of the group, experiences of CBT as applied to LGBQ mental health, and recommendations to improve the group. The qualitative survey schedule was piloted with a member of staff within the service in order to refine the flow of the survey.

Table 1. Qualitative survey items

Participants

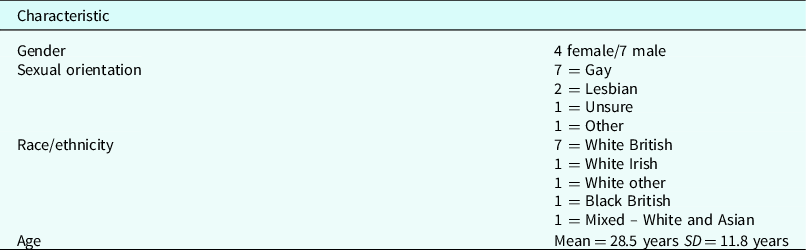

Following approval, a database of all service users who had previously attended and completed the LGBQ Wellbeing Group were collated. All past service users who had completed the eight-week group and had consented to research follow-up were subsequently invited via email to complete an online survey (n = 59). The survey was hosted online using Microsoft Forms and service users were not required to provide their name or any other identifying information. Of those who were invited, 18 people completed the qualitative survey between January and February 2020 (response rate of 30.5%). Participants were permitted to provide as much detail as they wished in their responses, with those providing qualitative responses spending an average of 36 minutes engaging with the survey. Participant demographics are provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of sample (n = 11)

Analysis

Survey data were analysed using qualitative content analysis (QCA) (Hsieh and Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005; Krippendorff, Reference Krippendorff2018), in order to inductively explore how participants experienced the LGBQ CBT wellbeing group. QCA has been defined as a method for systematically describing qualitative data by assigning successive parts of the text to the categories of a coding frame (Schreier, Reference Schreier2012). For the purposes of this study, we held in mind the particular focus of this evaluative exercise: that of seeking to explore participants’ experiences of the CBT group. Krippendorff (Reference Krippendorff2018) offers a broad framework for utilising QCA in diverse research settings, and demarcates QCA as an iterative process that typically involves (1) collating and coding data; (2) contextualising data by describing its content and conveying its meaning with reference to similar or dissimilar quotes; and (3) relating the findings to a research question.

In terms of the analytic process, one researcher (C.L.) repeatedly read the qualitative data for each successive participant, creating a list of open codes arising from the themes found in the data. Examples included: ‘unhelpful stereotypes’, ‘a non-judgement space’ and ‘perceiving LGBQ focus as unrelated to difficulties’. These codes were subsequently shared with the third author (D.H.) and refined until it was felt that the codes generated captured the essence of the data. A process of numeration aided the successive refinement of codes so that finalised themes selected were those which were experienced by a sufficient number of participants. In line with the aims of the survey, the themes are presented in three parts: helpful aspects of the group, unhelpful aspects of the group, and suggestions for group enhancement.

Results

Demographics

Table 2 summarises the demographic make-up of the sample. Seven participants chose to answer the survey anonymously. Accordingly, demographic data are only present for the remaining 11 participants.

Content analysis

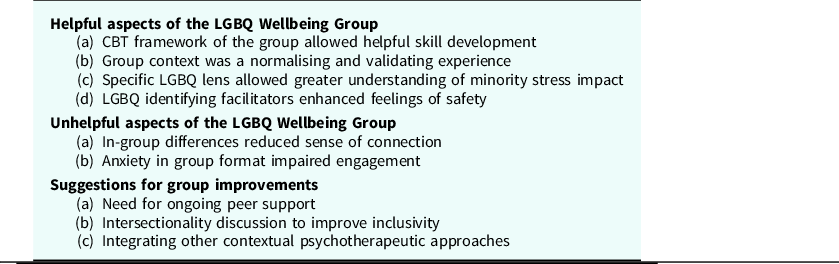

For helpful aspects of the group, four themes were identified, whereas for unhelpful aspects, two themes were identified. Finally, three themes were identified for suggestions for group improvements. These themes are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3. Theme table

Helpful aspects of the LGBQ Wellbeing Group

(a) CBT framework of the group allowed helpful skill development

Sixteen of the participants reported experiencing the CBT frame of the group as a particularly helpful component. For many, CBT was experienced as providing useful tools to better make sense of their thoughts, feelings and behaviours and to identify and challenge unhelpful thoughts and behaviours:

‘I feel like it is a really useful tool to help understand and unpick beliefs that have been developed since childhood. Growing up queer often involves creating a set of coping mechanisms to hide yourself and keep yourself safe. CBT can help you to reveal those behaviours as potentially damaging in adulthood instead of the protective behaviour that we may believe it to be.’ [P10]

‘CBT in the group format was definitely more successful than one-to-one I found.’ [P18]

For others the CBT content provided useful strategies to use to continually support the management of difficult emotions following the end of the group:

‘I found learning about CBT to be incredibly helpful, especially in terms of preventing catastrophising which could lead to a panic attack. It’s been over year since I’ve been at the sessions and I still go through the emotional/anxiety strain in the situations where I have to work at consciously applying CBT, but yes overall it has proved a very useful tool.’ [P18]

(b) Group context was a normalising and validating experience

In addition to the CBT skills and techniques, 15 participants reported that they acquired additional benefits from the group structure. In particular, participants variously spoke of how the group setting gave them a space to be acknowledged and heard by others in a group format. For many, this was the first time their experiences were heard in this way, which was felt to contribute to a reduction in shame, through increased confidence and validation:

‘I had such an enriching and inspiring experience attending this group. First of all, it gave me the opportunity to talk about my mental health issues (rather than to a wellbeing practitioner) with other members who are facing the same problem as me, to share my experience and at the same time giving them some tips which I found helpful to better tackle mental health problems. It was also helpful for me in getting to hear other members talking about their problems, experiences and some of their tips they found helpful. The whole experience attending this group really made me more confident in talking about my feelings, solving problems, in scheduling and setting goals and above all in identifying my values and doing activities based on that.’ [P17]

For others, being able to hear other participants’ narratives and to discuss lived experiences and challenges specific to the LGBQ context openly was therapeutic in and of itself. In these instances, it was felt the group provided a normalising effect, whereby hearing others share their struggle allowed some to feel validated and articulate their own difficulties:

‘Very helpful. It was humbling to hear about the backgrounds of some of the other attendees and to also see of my own experiences reflected in theirs. I learned how my childhood experiences have indelibly influenced who I am today. I learned that I am kinder than I think I am, just not to myself.’ [P11]

Meanwhile, for others, the group format allowed space to challenge unhelpful previous experiences and stereotypes, through exposure to different perspectives:

‘It was a very healing experience, hearing the similar and very different struggles of others in the queer community. Specifically, my queer femme bubble has shunned gay men for quite some time, having felt oppressed by and unsupported by gay men over the last decade… Being in, predominantly, a group of gay men, and as intimate and safe an environment as group therapy, allowed me new, reciprocal and compassionate experiences with gay men who had their guard down and their ears open. That was very healing re: my real and perceived wounds from the London gay community.’ [P8]

It seemed for this participant that being in a group format with other members of the LGBQ+ community had offered an opportunity to be heard and acknowledged, thereby challenging negative internalised beliefs about LGBQ people.

(c) Specific LGBQ lens allowed greater understanding of minority stress impact

Participants reported that the specific LGBQ lens of the group was a valuable and helpful aspect of the intervention:

‘[The LGBQ focus was]… really helpful. Personally, a large part of my difficulties stemmed from being LGBT+ and the experiences, feelings and sense of identity within this. Relating critical/automatic negative thoughts to internalised homophobia, micro-aggression and then core beliefs relating to me being LGBT was really important.’ [P4]

‘The LGBT lens was so useful, learnt to see how my experience chimes with others, and how homophobia in society has made things difficult for us.’ [P16]

It was widely felt that the LGBQ focus of the group connected directly to participants experiences of distress. This allowed participants the space to begin to make sense of their sexual minority identity and how their experiences of minority stress had perhaps shaped their experiences. In particular, psychoeducation around homophobia and how stigmatising social contexts can lead to internalised negative beliefs was an aspect found to be of significant value.

One participant reported that they initially felt the LGBQ element of the group was not necessary for them personally to understand their difficulties, but did acknowledge that it was helpful for them in some ways:

‘To be honest I struggled slightly with the LBGQ aspect to the group. Whether rightly or wrongly, I didn’t feel being my being gay had anything to do with the issues I was facing and hence I felt a little shoehorned into this group. That being said, maybe having had that opportunity within an LGBT focused group did make exploring some issues easier than it would have been in a non-LGBT group.’ [P15]

(d) LGBQ identifying facilitators enhanced feelings of safety

Having some group facilitators who openly self-identified as LGBQ themselves was highly valued by the group participants. It seemed that the presence of LGBQ identifying clinicians within the group provided a particularly safe space for participants, where they felt secure and not judged:

‘It was hugely helpful to be in a room that felt welcoming, non-judgmental and queer.’ [P10]

‘Having three facilitators was good and them being open about their sexuality.’ [P16]

‘Friendly, experienced and kind facilitators, who were also LGBT+/queer friendly really helped.’ [P4]

Unhelpful aspects of the LGBQ Wellbeing Group

Three themes were identified in relation to aspects that participants experienced as unhelpful and which limited or prevented their engagement.

(a) In-group differences reduced sense of connection

For five of the participants, the intra-group differences between members sometimes made it difficult for them to connect and relate with each other. In particular, age differences between members were frequently cited as barriers to engagement, in that participants had vastly different social contexts and lived experiences contributing to their LGBQ identity. For example, there appeared to be a notable difference between those who grew up in relatively more homophobic contexts versus those who were more confident in their identities due to wide-scale social change and greater acceptance, and this resulted in disparities within the group, which was felt to prevent connection and mutual understanding.

‘The age differences, interestingly enough, caused some barriers because of the differences over time of being gay in society, coming out etc.’ [P6]

‘Another difficulty was not feeling gay enough/not being out or feeling proud/feeling like a terrible gay person was activated within the group which created comparison making in the group.’ [P6]

(b) Anxiety in group format impaired engagement

Some participants also expressed how the group format prevented their deeper engagement. For five of the participants, the group format was experienced as overwhelming and they struggled to share their experiences openly with other group members.

‘I find it hard to be vulnerable or tearful/emotional around people, let alone strangers, and get tearful when discussing difficult topics that I have experienced so I don’t feel comfortable sharing, I am not sure how the group could have supported me in that. For example, I was hesitant in discussing the homework around tackling negative core beliefs because battling low-self-esteem and negative self-talk is a tough and ongoing process of trying to uproot something that is so entrenched.’ [P9]

Other participants reflected on how their psychological difficulties at the time of the group, such as low self-esteem, were experienced as a barrier to group engagement:

‘On reflection I was quite depressed at the time and not confident in speaking about my issues at all which in hindsight limited my contribution in the group. Feeling unworthy to contribute and a sense that topics may be too emotionally intense for me to talk about in a group.’ [P4]

Suggestions for group improvement

After sharing their experiences of helpful and unhelpful aspects of the LGBQ group, many of the participants identified aspects that they felt would enhance future groups in light of their experiences, with three key themes being identified.

(a) Need for ongoing peer support

Emerging throughout several of the participant responses were requests for the inclusion of some form of additional peer support. Five of the participants reported how they felt the inclusion of space outside the group would support and strengthen their relationships with other members, which in turn, would support group engagement:

‘[The group could be improved by]… a space outside the group to discuss the topics in a one on one setting. I felt like I couldn’t fully understand the implications of the learning on my life as I needed to talk it through to really process it.’ [P10]

‘I would have loved to if you could help with the initial set up of after care group because we shared so much during I think we all were slightly caged about setting one up ourselves. We met twice and never did again.’ [P13]

‘An ongoing LGBT group or drop in would be helpful – the informal one never took off.’ [P16]

(b) Intersectionality discussion to improve inclusivity

A particularly important aspect for group development was felt to be the inclusion of an intersectional lens for situating and discussing LGBQ mental health issues. Three of the participants spoke of how they felt an intersectional and inclusive lens should be used throughout the group.

‘That being said, the T [Trans] perspective/lens must be added to make this a fully inclusive service. The queer community has so much to learn from our trans sibling’s oppression and journeys. Many trans people are lesbian/gay/bi/queer and must be invited into, and included in our queer, life-saving services.’ [P8]

It was felt that an intersectional lens should include attention to specific LGBQ+ issues beyond male sexuality and identities, to include issues relating to different gender identities, ethnic identities, and religious belief systems and how these various identities co-exist and create different contexts in which experiences of mental distress vary:

‘More focus on issues that queer women face; I think while there are similarities in the experiences of gay men and women, I think the differences and the challenges that come with this, are important to acknowledge too. Also, people who are not out, whether out of choice or circumstance, face certain difficulties. Coming out is not always as clear cut so acknowledging the nuances and challenges navigating that could be fruitful.’ [P9]

‘Race and LGBT issues a little more perhaps.’ [P16]

(c) Integrating other contextual psychotherapeutic approaches

Whilst a significant proportion of participants reported positive experiences with the CBT aspects of the group, three participants desired for the inclusion of contextual therapies, such as counselling or acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) alongside CBT:

‘I feel it’s part of a solution that requires other therapies as well. In my experience CBT helps stop unhelpful thought processes while other talking therapies like counselling help understand how you got to feeling bad, and understanding that is an important part of healing (for me, anyway).’ [P18]

‘It seemed to help at the time but having since learnt and successfully adopted ACT I much prefer that approach. I find ACT much easier and more beneficial to implement.’ [P3]

With the desire for inclusion of other psychotherapeutic modalities came the ready recognition of the particular challenges the LGBQ community faces and the limits of psychological therapy for tackling these:

‘However, I do recognise that there is a limit to what I as an individual can do to, as structural inequality, discrimination and circumstances outside of your control still exists and has a big impact on my mental health.’ [P9]

Discussion

By utilising a qualitative methodology, we have inductively explored the experiences of adults who attended a LGBQ CBT wellbeing group for anxiety, depression and stress. Below we discuss our key findings with reference to wider literature and conclude with some recommendations for service development and practice.

Helpful aspects

Emerging strongly from our findings was broad support for the LGBQ focus of the group. In particular, participants found that the LGBQ focus offered unique value, in that it enabled a safe, validating and affirming space, to make sense of their difficulties through a CBT lens. Moreover, for several of the participants, the presence of some group facilitators who also openly identified as LGBQ created a sense of safety, trust and community. Interpersonal congruency, or perceived similarity between individuals, can facilitate group cohesion (Lott and Lott, Reference Lott and Lott1965). Limited therapist self-disclosure can also promote a positive therapeutic alliance (e.g. Henretty et al., Reference Henretty, Berman, Currier and Levitt2014) and this is true of group psychotherapy as well as individual therapy settings (e.g. Yalom and Leszcz, Reference Yalom and Leszcz2005). The current study, like others (e.g. Kronner, Reference Kronner2013; Kronner and Northcut, Reference Kronner and Northcut2015), demonstrates that therapist disclosure of their sexual minority status when working with LGBQ patients can have the potential to promote engagement with the intervention through the perception of a shared lived experience, and enhanced sense of empathy, safety and trust.

These factors together seemed to bring abstract CBT concepts and skills to life and to make them more relevant and accessible, which enhanced learning. As research by Foy et al. (Reference Foy, Morris, Fernandes and Rimes2019) highlights, the LGBQ community may often perceive psychotherapeutic services as potentially discriminatory and not attuned to their specific needs. The results of this initial qualitative survey lend support to the notion that culturally adapted LGBQ interventions are likely to be experienced as helpful and can improve engagement, in that they enable an affirmative context through which to make sense of psychological difficulties. Secondly, beyond CBT techniques and skills, many participants shared how the group itself was experienced as validating and nurturing and how listening to others share their experiences was both normalising and de-shaming. This finding is broadly consistent with a large body of literature, which highlights the potential benefits of group therapy, and in particular LGBQ group therapies, in promoting wellbeing through the amelioration of symptomatology and the promotion of social relatedness and peer support (Pachankis et al., Reference Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, Rendina, Safren and Parsons2015; Pachankis et al., Reference Pachankis, Clark, Burton, Hughto, Bränström and Keene2020; Parra et al., Reference Parra, Bell, Benibgui, Helm and Hastings2018; Ross et al., Reference Ross, Doctor, Dimito, Kuehl and Armstrong2007). Specifically, research indicates that LGBQ group therapies may not only help to alleviate depression and anxiety but may also increase self-esteem and lessen levels of internalised homophobia (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Doctor, Dimito, Kuehl and Armstrong2007). Similarly, in their randomised controlled trial of an LGB-affirmative CBT group for young adult gay and bisexual men, treatment was reported to significantly reduce levels of depression, anxiety, alcohol use problems and sexual compulsivity (Pachankis et al., Reference Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, Rendina, Safren and Parsons2015).

Unhelpful aspects

Some of the aspects of the group perceived as unhelpful appear to be more generic and related to some of the more widely known difficulties that some people experience in attending therapeutic groups. This included intra-group differences, which some participants experienced as a barrier to their engagement, as well as anxiety in sharing in a group format. However, some of the differences were specific to being LGBQ. For example, where there were felt to be marked differences in lived experience between members due to the significant societal changes over time, which sometimes made it difficult for members of different ages to engage or relate to the experiences of others. Counter to this, however, a number of participants spoke of the need to ensure adequate attention to areas of intersectionality, such as having examples that stemmed beyond the experiences of cis-gendered, white, gay male identities. Others, however, spoke of how they experienced the diversity in the group as particularly healing as it offered exposure to experiences and perspectives that they might not have otherwise have engaged with.

Areas for improvement

Some of the suggestions for group enhancement emerged as a possible antidote to the identified challenges. In particular, the inclusion of a more integrated and formal peer support network was suggested to support relationships between group members and thus to remedy feelings of anxiety in sharing experiences. There were also requests for a more intersectional focus in the group. Intersectional approaches are situated in the understanding that individual identities are built on multiple different layers relating to different aspects of our socially defined selves, such as gender, gender identity, sexuality, race/ethnicity, social class, etc. (Parent et al., Reference Parent, DeBlaere and Moradi2013). Applying a more intersectional lens could include provision of examples and discussions which extended beyond stereotypical norms for sexuality, and seek to address how multiple intersecting minority identities related to race, social class, gender, etc. can result in multiple and intersecting forms of oppression, discrimination and stigma. Indeed, as acknowledged by Pollack (Reference Pollack2004), typically, CBT does not address the underlying structural roots of psychological dysfunction, but rather tends to decontextualise individual problems from social ones, generating a dialectic between the two. The authors are not aware of any LGBQ-specific therapy groups which focus on creating wider social change and promoting social justice. However, in other stigmatised groups, such approaches have been developed, for example Health At Every Size (HAES; https://haescommunity.com/). Although our CBT group did include psychoeducation and discussion regarding the impact of wider systemic issues, this finding suggests that participants may find it beneficial to focus more on how to take action about those issues, rather than focusing solely on the intrapersonal effects of stigmatisation and victimisation.

Limitations and future research

Although this study has provided initial exploratory evidence regarding what participants experienced as helpful and unhelpful aspects of their group experience, as well as recommendations for group enhancement, the study has a number of limitations. Firstly, the relatively low response rate and hence small sample in our survey precludes drawing substantive conclusions from the data. It is possible that those who did not respond to the survey may have had more negative experiences, which are not captured in this study. This may have led to a biased self-selected sample, which is not representative of all participant experiences.

Another limitation is that most of the groups from which the participants were recruited were designed to focus on issues about identifying with a sexual minority group. Although gender minority participants were welcome to participate if they had a sexual minority identity, it was only in recent groups that the different experiences of people with a gender minority identity were explicitly included with the programme materials. Now that the group is open to include transgender and non-binary participants regardless of their sexual identity, due to service user requests, further evaluation will be required.

Whilst this qualitative survey was useful in gaining initial exploratory insights from participants regarding their experiences, this does not preclude the need for further qualitative research, such as in-depth and phenomenologically focused interviews, which are capable of exploring participants experience and meaning-making in depth. In these instances, a deeper level of qualitative analysis, such as that offered through interpretative phenomenological analysis (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Larkin and Flowers2008) or thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006) would be advantageous. In addition, quantitative studies examining pre-to-post intervention changes on standardised measures (Hambrook et al., in preparation) are likely to be helpful in providing an evidence base for such interventions.

Conclusion and recommendations

Some of the themes identified in this survey study highlight generic and specific elements of the LGBQ group intervention that participants found helpful, and has provided ideas to take forward in planning future groups. We anticipate that although the data presented here stem from one particular service, the results should have wider utility in terms of service development and quality assurance. These findings may be of particular value to other services with CBT therapists who might consider establishing comparable group interventions for the LGBQ population. Emerging from our findings we offer a number of recommendations and considerations for future therapeutic practice and service development:

(1) The LGBQ focus of the CBT group fills a particular need and supports the acquisition of CBT skills and techniques in a safe and affirming space.

(2) Including out LGBQ identifying facilitators was experienced as helpful and aided the participation of group members.

(3) There is a need to consider setting up or offering a peer support group, or drop-in service, which might be either activated as a resource during the group, to enhance engagement and/or for aftercare, following discharge. To reduce the burden on services to provide this in the context of very limited resources, it could be purely peer led by service users.

(4) Where LGBQ groups are provided, these should incorporate focus on intersectional issues. For example, discussions could be invited regarding how race/ethnicity, gender identity, religion, age, social class and so on, can mean that experiences differ between individuals even if they share a minority sexual orientation.

(5) In addition to exploring the personal impact of multiple forms of oppression, it may also be helpful to include discussion about affirmative action that people can take to tackle oppression and discrimination in their own lives.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the service users who kindly shared their experiences of this group.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical statement

The project was deemed to be a routine service evaluation project, hence ethical approval was not required. Local approval was granted by the SLaM Southwark Directorate Education, Training and Research Committee (approval received 14/01/20). All authors abided by the Ethics Guidelines for Internet-mediated Research (BPS, 2017).

Key practice points

(1) A culturally adapted CBT group intervention developed specifically for sexual minorities is acceptable and perceived as offering something unique.

(2) A CBT lens coupled with a LGBQ specific focus is likely to enhance the utility and uptake of CBT by participants by being both targeted to areas of distress but also through the creation of a safe and affirmative space where participants feel understood.

(3) There is a need to acknowledge that the LGBQ community is heterogenous, rather than homogenous, in form and that diverse examples and clinical discussions, which incorporate recognition of intersectional elements is pivotal, to ensure that all group members are adequately engaged.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.