In 1600, Jacob Corneliszoon van Neck’s report of the second Dutch expedition to Indonesia was published in Amsterdam. When the second edition appeared the very next year, an engraving titled “How we lived on the island Mauritius otherwise named Do Cerne” was included in the report (fig. 1) (Anonymous 1601). As the first published image of the dodo, the flightless pigeon entered global history in the shadow of the 1598 Dutch expedition to Asia. Within a century, the bird was extinct. Footnote 1 In fact, all three identified species depicted in the engraving — the Mauritius giant tortoise (Cylindraspis), the dodo (Raphus cucullatus), and the Mauritius broad-billed parrot (Lophopsittacus mauritianus) — would be extinct soon after due to deforestation, indiscriminate hunting, and the introduction of nonindigenous predators such as rats, cats, pigs, and other animals. The Anthropocene extinction or the age of human-induced mass extinction was thus inaugurated. Although scholars suggest that James Watt’s 1784 design of the steam engine or atomic weapons testing in the 1960s initiated the Anthropocene as the period in which human activity has become the dominant force on the environment, European ecological imperialism from the 1500s onwards can be seen as an equally devastating origin story of our current mass biodiversity extinction (Yusoff Reference Yusoff2019; Lewis and Maslin Reference Lewis and Maslin2015). Often described as the Sixth Mass Extinction event, the most cataclysmic extinction event after the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction that saw the demise of nonavian dinosaurs around 65 million years ago, the loss of vertebrate animal species has, for instance, “moved forward 24–85 times faster since 1500 than during the Cretaceous mass extinction” (McCallum Reference McCallum2015:2498; see also Heise Reference Heise2016; Kolbert Reference Kolbert2014).

Figure 1. Artist unknown, Het tvveede Boeck, Journael oft Dagh-register…, plate 2. (From Anonymous [1601])

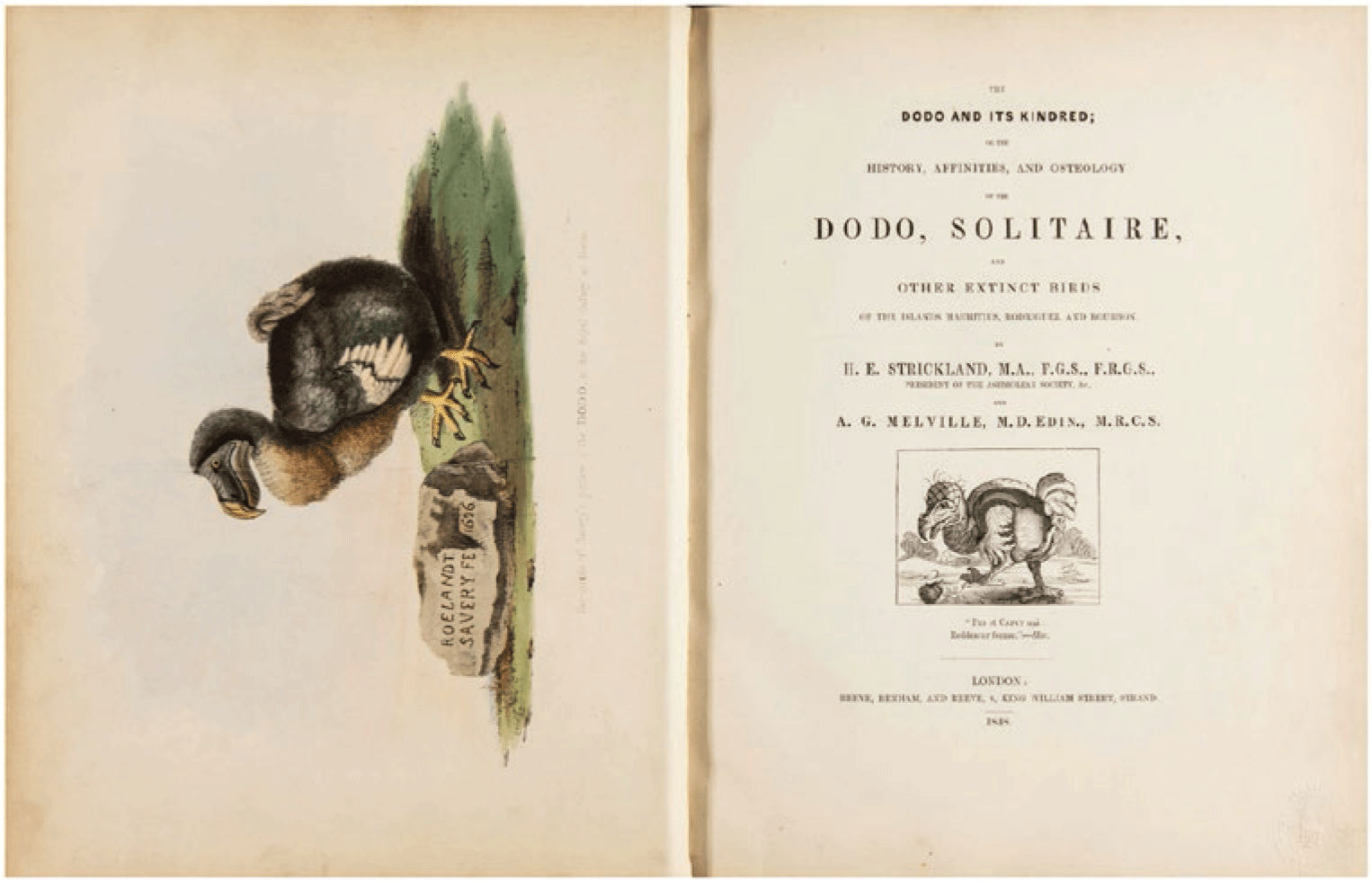

Among the many species that were condemned to extinction in the past 500 years or so under colonial regimes globally, it is the ill-fated dodo that became an early icon of the Anthropocene extinction (Strickland and Melville Reference Strickland and Melville1848; see also Parish Reference Parish2013; Cheke and Hume Reference Cheke and Hume2008; Pinto-Correia Reference Pinto-Correia2003; Fuller Reference Fuller2002; Quammen Reference Quammen1996; Hachisuka Reference Hachisuka1953). In 1847, the British naturalists Hugh E. Strickland and Alexander G. Melville published a book on the dodo based on the authors’ dissection of a specimen that had entered the University of Oxford collection in 1683 (fig. 2). In their introduction, Strickland and Melville noted: “These singular birds […] furnish the first clearly attested instances of the extinction of organic species through human agency” (1848:5). Shortly after the publication of the book, a life-size model of the bird was displayed at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London and seen by over six million people (Yapp Reference Yapp1851:147). By 1865, the dodo was squarely embedded in the popular imagination with the publication of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, in which the extinct bird initiates a “Caucus-race” (fig. 3). In tandem, an increasing awareness of human-induced species extinction led scientists to mine early modern visual representations and written accounts, some based on firsthand observation and others on hearsay, to better understand the fate of the doomed bird.

Figure 2. Skull of a Dodo, Tradescant Collection, Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Object No. ZC-11605. (Image © Oxford University Museum of Natural History)

Figure 3. John Tenniel, Alice Meets the Dodo, Wood-engraved illustration published in Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. (From Carroll [Reference Carroll1865] 1866:35)

While the etymology of the word dodo is still unclear, the Oxford English Dictionary traces the origin of the word to the Portuguese doudo, implying a simpleton or fool (Stevenson and Waite Reference Stevenson and Waite2011:421). The word first appeared in print in 1634 in a travel narrative by Thomas Herbert, a member of the 1627 English mission to Safavid Iran (1634:212). Stereotypes and platitudes flourished: dead as a dodo; an oversized bird with tiny wings; a species that went extinct because of its ineptitude to come to terms with the socioenvironmental transformations that were part and parcel of the global dispersion of Western European modernity. Footnote 2 Despite having never visited Mauritius, the Dutch physician Jacobus Bontius described the dodo as “slow going and stupid” and “easily taken by hunters” (1658:71). Footnote 3 The mischaracterization of the bird as stupid became entrenched in European natural histories. Even in the 18th century, the French naturalist Jacques Christophe Valmont-Bomare described the dodo as “very stupid” (1764:239) while Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon, one of the earliest naturalists to theorize ecological succession, indicated that the dodo’s sole purpose was to give us an idea of the heaviest of all beings (1770:480).

It is thus not surprising that when the Flemish artist Roelandt Savery completed around 10 paintings of the dodo, he visualized the bird as an overweight, immobile creature without any trace of a vivacious life force (Rikken Reference Rikken2014:401–43; Müllenmeister Reference Müllenmeister1988). Often considered to be one of the most important dodo paintings by Savery, the Mannerist landscape is striking in its staging of the fall of humanity (fig. 4). That the metaphor of loss was not set in a hoary Biblical past but in Europe’s colonial present is evident from the inclusion of the dodo — a bird that had been discovered by Europeans a few decades earlier — in the right corner. Savery’s corpulent dodo was reproduced repeatedly over the next few centuries. It served as a model for the illustration of the bird in Alice’s Adventures and as the frontispiece to Strickland and Melville’s The Dodo and its Kindred (see fig. 3; fig. 5). Upon encountering the painting in Berlin in 1845, Strickland had noted: “I was much pleased by finding a picture bearing the name of ‘Roelandt Savery, 1626,’ containing a figure of the Dodo, exactly like the one by the same artist at the Hague. […] The figure of the Dodo is in the usual attitude in which that bird is represented, but the beak is less hooked, and more like what we know to be its real form” (in Jardine Reference Jardine1858:ccxxxiv). Despite having studied only a few fragmentary bones in European collections, the British naturalist believed that Savery’s painting of the dodo was an objective and scientific representation and, in this sense, a clear indicator of the “grotesque proportions” and “gigantic immaturity” of the bird (Strickland and Melville Reference Strickland and Melville1848:iv).

Figure 4. Roelandt Savery, Das Paradies, 1626. Oil on oak wood, 80.7 x 137.6 cm. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister der Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ident. Nr. 710. (Image © Gemäldegalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz Fotograf/in: Jörg P. Anders; CC BY-NC-SA)

Figure 5. Hugh E. Strickland and Alexander G. Melville, The Dodo and its Kindred…, plate 1. (From Strickland and Melville [Reference Strickland and Melville1848])

Recent zooarchaeological analyses have, however, revealed that the bird had longer legs, a straighter neck, and a less bulky body (Angst, Buffetaut, and Abourachid Reference Angst, Buffetaut and Abourachid2011; Kitchener Reference Kitchener1993; Livezey Reference Livezey1993). Going by scale models, estimates of skeleton mass, and bone measurements, the mass of the bird appears to be around 22.4 lbs. as opposed to the 50 lbs. estimates provided in early modern accounts. In contrast to Savery’s corpulent dodo, the sinewy long-legged bird in the Het tvveede Boeck was then closer to the bird’s physiognomy. The transformation of the dodo into a languid corpulent creature, it seems, occurred in less than two decades. Arguably, the metamorphosis of the bird was substantially shaped by Dutch colonial environmental policy in Indian Ocean islands such as Mauritius, and it was Savery’s portrait of an obese bird set in a primeval landscape that profoundly determined how European audiences envisioned the dodo from the 17th century onwards.

Corpulence was already associated with the diseased body in 17th-century Europe (Stolberg Reference Stolberg2012). The stigmatization of fatness, however, took on a more disturbing biopolitical weight when applied to worlds beyond temperate Europe. Here is the French Jesuit Jean-Baptiste Du Halde echoing the environmental determinism of his time in a 1735 history of China: The people who inhabit fat and fertile lands are usually very voluptuous and not very industrious (1735:670). In Europe’s imagination, the obesogenic tropics inevitably led to indolence and weakness. And it is into this colonial theatre of monstrous corpulence that we must also cast the hapless dodo. While much has been written on the biotechnological apparatuses that expedited the extinction of the dodo, the role of early modern aesthetic regimes and artistic cultures in framing ecocide as the story of Europe’s global modernity still bears underscoring.

It is in relation to the complex matrix of imperialism and environmental determinism that we might also revisit the science writer David Quammen’s oft-quoted requiem to the last dodo:

Imagine a single survivor, a lonely fugitive at large on mainland Mauritius at the end of the seventeenth century. Imagine this fugitive as a female. She would have been bulky and flightless and befuddled — but resourceful enough to have escaped and endured when the other birds didn’t. […] Imagine that her last hatchling had been snarfed by a feral pig. That her last fertile egg had been eaten by a monkey. That her mate was dead, clubbed by a hungry Dutch sailor, and that she had no hope of finding another. […] She didn’t know it, nor did anyone else, but she was the only dodo on Earth. When the storm passed, she never opened her eyes. This is extinction. (1996:275) Footnote 4

Bulky, befuddled, and aged, she — the abject dodo — can only elicit remorse and deep sorrow; all we hear is the dodo’s song of despair as the bird faces modernity and eventually dies. Quammen’s elegy pivots on the dodo’s inability to cope with the arrival of European modernity in the form of a hungry Dutch sailor and a feral pig in pristine Mauritius leading to the unfortunate, but foreseeable, extinction of the “slow going and stupid” bird.

The rhetoric of extinction as incommensurability was not Quammen’s alone. In 1847, Strickland and Melville had seen the bird’s fate through the lens of a fetishized econostalgia for a primeval precolonial wilderness:

We cannot see without regret the extinction of the last individual of any race of organic beings, whose progenitors colonized the pre-adamite Earth; but our consolation must be found in the reflection, that Man is destined by his Creator to “be fruitful and multiply and replenish the Earth and subdue it.” (1848:5)

The “regret” of human-induced extinction could, however, be tempered, according to the authors, by conjoining stewardship and ecological domination through Genesis 1:28. While the assurance of a moral compass offered by Christian eschatology has far less purchase today, recent artistic projects such as Harri Kallio’s photographs of life-sized sculptural models of dodos placed in an imagined pristine Mauritius (Kallio Reference Kallio2004; see also Bezan Reference Bezan2019) and David Beck’s bronze reconstruction of the bird in the manner of 18th-century portrait sculpture now serve as a mode of memorializing or remembering the trauma of colonial extinction (fig. 6).

Figure 6. David Beck, Dodos en Suite, 2010. Bronze, each approx. 38.1 x 14.0 x 14.0 cm. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the artist in honor of Elizabeth Broun, 2016. 53A-G. (Image © Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Visualizing extinction as a form of ecological mourning nonetheless conveys far more about human perceptions of the environment than about the environment itself. As Ursula K. Heise puts it: “biodiversity loss comes to be felt and understood as a sign of something that we lost in the course of modernization and/or colonization” (2016:24). The affective power of visualizing extinction, consequently, becomes an ekphrastic synecdoche for us, the human species, to come to terms with both the trauma of the global dispersal of Western European modernity and a future in which our own survival is under imminent threat. Thus, rather than naturalizing nature, that is, reading visual representations in the colonial archive as somehow offering a direct access to the historical dodo, a critical examination of the ways in which the Other — nonhuman or otherwise — was historically constituted via representational and discursive norms offers a framework to comprehend the epistemic violence through which ecocide was established as the de facto story of European modernity’s global teleology. That European modernity was directly responsible for the extinction of the dodo was certainly not contested in the historical archive. As early as 1639, the German diplomat Johan Albrecht von Mandelslo had witnessed the wholesale slaughter of birds in Mauritius “with Cudgels” (in Olearius 1669:198). In 1648, a report of the Dutch sailor Willem van West-Zanen’s 1602 account of Mauritius was published with an engraving depicting the slaughter of dodos, sea cows, and other species endemic to the island (fig. 7) (West-Zanen Reference West-Zanen1648). Although the bird depicted in the engraving was a penguin — rather than a dodo — the accompanying verse clearly identified the bird as a dronten, a Dutch word meaning swollen and often used in early modern sources to describe the dodo. Footnote 5

Figure 7. Willem van West-Zanen, Derde voornaemste Zee-getogt…, plate 3. (From West-Zanen [Reference West-Zanen1648])

It is noteworthy in this context that, despite archival excess, that is, the manifold presence of the bird in travel narratives, literary accounts, the visual arts, and scientific discourses, we still know very little about the lived reality of the bird until its extinction in the 17th century. As performance studies scholar Rick De Vos notes, histories of nonhuman extinction “are shaped by their absence and their extirpation, by stories of human agency, exploitation and violence rather than those of avian survival and endurance” (2017:4). In a similar vein, animal studies scholar Erica Fudge recently asked in her critique of Francis Gooding’s essay on dodos and the nature of history, “But can animals be likewise recognised as change-making creatures; do animals, in short, have agency?” (Fudge Reference Fudge2006; Gooding Reference Gooding2005; also see Freeman Reference Freeman, Freeman, Leane and Watt2011:153–68). While Fudge proposes “other models of history” that might allow us to excavate how dodos, and not just humans, “shaped the past,” it is worth underscoring that we are yet to fully understand the ecology and morphology of the bird. Put differently, there is still no archive that might offer insight into the bird’s resilience or agency before and during Dutch colonialism in Mauritius.

Even though post-2005 excavations at Mare aux Songes, a marsh in southeastern Mauritius, have revealed innumerable dodo bone fragments, very little is known about the bird beyond the fact that the dodo fed on fallen fruits and coexisted with other species such as giant tortoises before its extinction due to anthropogenic alterations in the island’s fragile ecosystem (Rijsdijk et al. Reference Rijsdijk, Hume, Frans Bunnik, Florens, Baider, Shapiro and van der Plicht2009, Reference Rijsdijk, Hume, De Louw, Meijer, Anwar Janoo, Boer and Steel2015). Indeed, despite recent skeletal analyses that have established that the dodo was indisputably a resilient species, paleontologists have noted that they are only “starting to fill in major gaps in our knowledge regarding the Mare aux Songes, the dodo, and Mauritian paleo-ecology in general” (Claessens et al. Reference Claessens, Meijer and Hume2015:29). The fragmented understanding of the bird’s anatomy and ecology is in part because, except for one single almost entirely complete skeleton discovered around 1904, all the skeletal reconstructions of the bird from the 17th century onwards were composite and thus partial. Moreover, the skeletal material excavated in Mare aux Songes, and elsewhere in Mauritius, were vociferously collected by museums and research institutes without any data regarding specific depositional settings. The fragmented skulls, beaks, and pieces of bones that one encounters in museums and university collections consequently do not offer any clue regarding the dodo’s place in the world. Pathologized, specimenized, and museumized, the hapless dodo can then only bear silent witness to the finitude of colonial exceptionalism.

As for us, in lieu of the “song of the dodo,” to borrow from the title of Quammen’s book on island ecologies, all we can hear today is the silence of extinction. Is the trauma of extinction the only recourse for a species that could not ostensibly come to terms with the purported natural and inevitable progress of European modernity? Is incommensurability extinction? In lieu of “performing against the catastrophe,” as we are called to do in the title of this issue section, all I can present is the uncanny stillness of a bird silenced, misrepresented, mocked, and ridiculed in Europe’s art historical archive. As nonfigurative rupture, this silence disrupts the human — or more specifically the European — conviction in speech as the site for the articulation of agency.