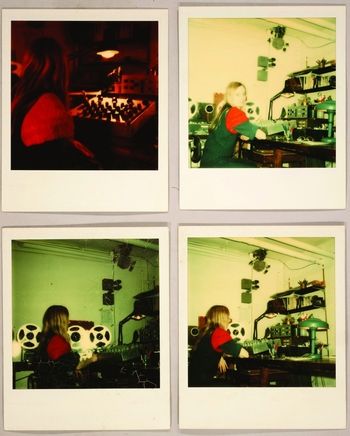

I am listening to a tape that belonged to US experimental composer Maryanne Amacher. Many tapes belonged to Amacher and this one has been recently digitized. At once both transfixing and boring, drips, drops, exhalations and whirs gently punctuate its thirty-five minutes, though nearly half its duration offers little more than hiss-filled stasis – near silence – perhaps, ‘almost nothing’. Labelled ‘Pier Six Edited 1976’, this tape seems to find Amacher in the middle – a tiny sliver of the middle – of an extreme duration listening project: between 1973 and 1978, Amacher treated herself to a fourteen hour/day dosage of the Boston Harbor's sounding life, courtesy of a dedicated, open-air 15 kcl telelink connecting her Cambridge studio with a Neumann microphone perched in the window of the Boston Harbor's ‘Fish Pier’. The feed was FM quality, in mono. Poised to commit any – whatever – incoming sounding moment was Amacher's ReVox B77 reel-to-reel tape machine, coupled with the mixer and telelink. This interval of hiss-filled stillness she will call a ‘long distance music’ (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Maryanne Amacher in her Cambridge Studio with phone blocks. Courtesy of the Maryanne Amacher Archive.

Amacher's Harbor tapes – and other tapes, too, from a series she called ‘Life Time and its Music’ made during her tenure at SUNY Buffalo as a Creative Associate (1966–7)Footnote 1 – criss-crossed the United States between 1967 and 1980 as she developed the twenty-two installations that came to comprise the series City-Links. Each part in the series was a little different. In US cities across the Northeast, Southeast, and Midwest, City-Links’s telelinks connected one to as many as eight meticulously placed remote microphones to radio stations, galleries, or museums, where Amacher mixed the live-feeds – sometimes cinched by the Harbor material, ‘Life Time’ tapes or accented with an instrumentalist – for broadcast or performance. As though indexing her long-term Harbor cohabitation, these durations were typically expansive: a twenty-eight-hour broadcast (City-Links #1 at WBFO Buffalo 1967), a six-week long telelink transmission (City-Links #9 at the Walker Art Center, 1974), and two-months’ worth of live feed (City Links #12 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, 1974).Footnote 2

If, as this volume's introduction suggests, ‘tape bears witness to history’, City-Links underscores that tape cannot be a modest witness: tape's standpoint is at once situated, partial and insistently embodied, as Donna Haraway might insist.Footnote 3 Implicated in Cold War technoscience and in struggles against its imperial consequences, Haraway's analysis finds ‘Home, Market, State, School, Clinic, Church’ and other places of paid work idealized from the perspective of advanced capitalist societies transforming amid new technologies, high-tech capital needs and dispersed social relations. The connective logics of City-Links, too, register these implications. City-Links’s tapes and telelinks interleave sounds of discipline, production, exchange, and consumption across heterogeneous social and institutional locations careening, differently, amid the violence of deindustrialization during the 1970s: Exchange National Bank (Chicago) and Carson Pirie Scott (Chicago); Bethlehem Steel (Buffalo); General Mills (Minneapolis) and many, many others.Footnote 4 Less concerned with analytics of storage or a Kittlerian mnemotechnics so often cleaved to phonography, this article interprets Amacher's tapes in and as the long distance wagers in which the telelink enrolled them – a meditation on social location and ‘high-tech’ embodiment and ‘geometries of difference’.Footnote 5

To adapt Ken Wark's sharp commentary, the ‘messy business of making science’ – or with Amacher, connecting musics, tapes, links, phone calls – embraces its implication in nets of power, processing and reinforcing of metaphors not of its making, and its dependence on a vast cyborg apparatus, according to Haraway.Footnote 6 While the tape-telelink coupling is surely a mechanical wager – the ReVox B77 reel-to-reel connected to the mixer and the mixer to the phone block's incoming feed – it also proffers what she calls a ‘figuration’: a ‘performative image that can be inhabited’.Footnote 7 If a nexus of critical media operations – cutting, splicing, looping, rewinding, spooling – articulate tape within the phonographic regime's attenuation, this article proposess contrasting figures, culled from this tape's long distance adventures in City Links. The telelink surely conjures the ideological image of the network in and through its point to point connection.Footnote 8 Yet, an analysis that takes seriously the standpoint of the cyborg apparatus also discerns in City Links’s tapes, shuttling restlessly between the telelinks’ networked point-to-point warp, a weft suggestive less of networking than weaving – at once a contested and complicit mesh of dispersed social locations, high-tech capital and heterogenous logics of connection and long-distance embodiments.

And so, more than a framing gambit, this essay makes a sustained and experimental effort to materialize Amacher's Harbor tape within its writing, redoubling tape in the place of the long-duration Harbor feed-in but also, more broadly, performing some of the temporal intrusions and material dispersions convened by the tape–telelink couplet on the page (as Amacher's own writing also attempts). This experimental inhabitation passes relentlessly between ‘tape’ and ‘telelink’, sounding their differential weave in multiple registers of analysis: the aesthetic, embodied, social, political, economic. Attuned to a critical poetics of locational dispersion and manoeuvre, this lyrical article plays Amacher's Harbor over (sometimes behind, sometimes against) six short and allusive scenes.

* * *

This tape – as gulls squawk amid the recording's hissy stillness – casts me into the warp and weft of City-Links #13 (‘Incoming Night – Blum at Pier 6’). Amacher's in-studio Harbor feed has been temporarily re-routed to 40 Massachusetts Avenue – the Center for Advanced Studies at MIT (hereafter ‘CAVS’) – where she helmed the live mix for a late night performance, 11:30pm–3am on 8 May 1975.Footnote 9 Eberhard Blum – flautist, vocalist and signal interpreter of Feldman, Cage, and Schwitters – has joined Amacher's Neumann at the Pier, where he improvises.Footnote 10 Another tape, likely recorded in MIT's anechoic chamber and woven, live, with this mix, draws Blum – sighs, whistle tones, breaths pressed through pursed lips – very, very close.

The installation series that follow City-Links, starting in 1980Footnote 11 – Music for Sound Joined Rooms and the Mini-Sound Series – extended the modular usage of pre-recorded material that indexed social and institutional weave, in many City-Links projects. No longer telelinked, these two series turned towards sound's dramatic architectural staging, subordinating musical material to three-dimensional sonic shapes and contours – ‘sound characters’, as Amacher called them, that might quiver, coil, or slither in air – as her primary horizons of narrative and dramaturgical possibility.Footnote 12 City-Links’s decade-plus interval also braced the psychoacoustics research programme she called ‘Additional Tones’, whose paradigmatic representative ‘Head Rhythm & Plaything’ opens the first of only two commercial releases, Sound Characters: Making the Third Ear.Footnote 13 ‘Head Rhythm’ is bracing: patterned, sinusoidal tone bursts coax pulsing difference tones from the basilar membrane, sharpening a biomechanical divergence between stimulus (incident sound) and reception (frequency analysis) for radical contrasts in auditory dimension, a contrapuntal prerogative in which tessitura becomes inextricable from sounding location on the auditory pathway.Footnote 14

Amacher wrote voluminously and her archive teems with stunning unpublished work.Footnote 15 The especially aphoristic text ‘Long Distance Music’ appears nested in a works list spanning 1967 to 1971, which includes project descriptions of In City (also known as City-Links #1), flanked by a series of Fluxus-style text pieces that differently extend and complicate this text's account.Footnote 16 Unfolded unevenly in short paragraphs, single sentences and the odd stand-alone fragment across just two and half pages, Amacher's tone is poetic, but her explication of ‘long distance music’ is systematic. A few excerpts, from the text's first paragraph sets up not one but three proposed practices of ‘long distances music’:

Right now we do not make music unless we are in the same room together. Music is made ONLY between men and women in ONE room, ONE field, or in ONE building between rooms through loudspeaker and microphone transmission.

[. . .]

The music we make is confining us to ONE PLACE situations ALL THE TIME. Receptive to our own structure ONLY as we are making them.

[. . .]

Long-distance music is developing occasions where boundaries of ONE PLACE situations can vanish, bringing spaces distant from each other together in time.

These ‘ALL CAPS’ interruptions initiate a suggestive interpretive itinerary. Throwing ‘ONE’ into relief throughout the text's first half isolates the point-like locations that it aspires to connect in and as a ‘long distance music’. A second interruption, however – ‘ALL THE TIME’ – clarifies that this connection is also a question of socially conjugated time. To become a ‘long distance music’, Amacher's ‘ONEs’ must also be drawn into the same durative present.Footnote 17 After proposing three such musics at the text's mid-point, her provocative ‘ONEs’ recede into a lowercase flow and more speculative phrasings take up their ‘ALL CAPS’ energy: ‘OUTSIDE OUR OWN STRUCTURES . . . WE ARE HEARING IN MOTION AND IN STILLNESS’, she writes, ‘WE BEGIN TO HEAR EACH OTHER MUCH BETTER IN THE PLACE WE ARE IN.’ Once linked, the ‘ONEs’ of Amacher's ‘ALL TIME’ imaginary conjure a listening that lingers near the subjective mood: conditional and open-endedly ongoing.Footnote 18

Amacher's first ‘long distance music’ relies on ‘remote circuitry’, presaging the Harbor feed's technical protocols. City-Links streamed over ‘leased lines’, ad hoc point-to-point connections that wired many different transmissions throughout the 1970s: Muzak, live sporting events, on-site radio broadcasts, and amateur radio, to name a few.Footnote 19 Comprising a movable, inconspicuously placed ‘phone block’ – designated by the ‘2MT-4461’ at the top of the Special Service Order (see Figure 2) and coupled with a Shure 668 microphone mixer – Bell field engineers installed and removed leased lines, rentable on the cheap. Amacher paid $30 for her Harbor-side phone block installation, plus a tariff for non-commercial transmission across eleven nautical miles, according to working notes for City-Links #9 (1974).Footnote 20 Amacher's feed linked her studio with the Harbor alone, a dedicated connection that admitted no incoming calls and secured the ‘ALL THE TIME’Footnote 21 protocol that structures the first half of the ‘Long Distance’ text.

Figure 2 Maryanne Amacher places a protective box for the microphone mixer at Pier 6.

Perhaps surprisingly, Amacher's second and third ‘long distance musics’ both excise the telelink entirely, confabulating two additional linkless listenings that traverse both much vaster and much smaller distances (respectively) than her intracity Harbor lines. The text piece ‘Green Weather’ is named but not cited at any length in the ‘Long Distance Music’ essay, though it directly follows the essay on Amacher's typewritten page. An excerpt from the first of ‘Green Weather's’ three brief paragraphs:

There are no electronic links. We make a special occasion to listen for each other, even though we are at distance points in the world. Playing music in our own places, New York, Los Angeles, Rome, Tokyo.

Though ‘Green Weather’ could readily fit Amacher's first remotely circuited long-distance protocol,Footnote 22 its emphatic linklessness underscores that all three protocols unfold in concert and in conflict with what Avital Ronell calls a pre- or para-technological techne.Footnote 23 While Amacher's punctual ‘ONEs’ dramatize ‘Long Distance Music's’ pressures on socially conjugated time, ‘Green Weather’, performs a differently nuanced long-distance linkage on the page. ‘Green Weather’ intrudes on ‘Long Distance Music’, yet ‘Long Distance Music’ also extrudes ‘Green Weather’, a relay (or delay) that links the two by dramatizing the impossible timing of their interimplication, etched into both Amacher's writing and the hissing tape it presages prior to hooking up the Harbor feed in 1973.

The point-to-point connection roils with broader questions about the materialization of bodies and mind–body relations across an uneven high-tech social and political field. Amacher's third ‘long distance music’ remains, also, linkless but traverses much smaller (‘long’) distances than ‘Green Weather’: ‘hearing and seeing 10 blocks away’, she specifies, means hearing ‘what is sounding far-away and close up at the same time’.Footnote 24 Here, listening in situ Footnote 25 aims not for a verisimilar imprint of the site – that hallmark of soundscape composition – but for a listening modelled on the point-to-point connection secured by the leased line.Footnote 26 Unlike the interleaved (but suggestively underdetermined) bodies of ‘Green Weather’, this listening seems to clasp both ends of the leased-line at once and a body at once dispersed and rematerialized in concert with the speeds and durations of an ‘ALL THE TIME’ networked imaginary.

Lingering with Amacher's text, homologies between long-distance music and long-distance dialing become suggestive (and, to me, nearly irresistible). This homology, in other words, summons ‘the telephone’ as a tantalizing interpretive horizon for ‘Long Distance Music’ and for City-Links, more broadly. The variable social and bodily geometries roiling Amacher's text, however, make different demands on this interpretive gambit. To speak of ‘the’ telephone is to always-already mistake one for two. One telephone conjures another, poised and waiting on the other end of the line. With this, ‘the’ telephone admits otherness at its core, with a ‘call’ necessarily late to a connection it reveals to have been (always)-already in place: not ‘yes’ or ‘hello’, but yes-yes, hello-hello.Footnote 27 If telephone conjure commingling, it is ‘only ever almost there’.Footnote 28

Dissimulating its two-in(or as?)-one, ‘the telephone’ is insolent. Telephonic redoubling – the phone call – interrupts, all the ruder for its impossible timing. Yes, Amacher is not taking calls on her dedicated 15 kcl line, but in artworks, Avital Ronell suggests, redoubled telephones summon not only the caller on the other end of the line, but also by so doing also query text's ‘veiled receiver’.Footnote 29 Film is Ronell's preferred exemplar.Footnote 30 Disembodied voices might sometimes direct the diegesis by roving, uncanny and horrifying, over telephone lines, but the telephonic aperture also ‘makes felt a connection with reception history’ that cannot be fully claimed in and as the acousmêtre’s thingified authority.Footnote 31

The hiss-swathed breaths that accompany my writing surely materialize Amacher, their receiver, at the ReVox, in the studio or behind the mixer at the CAVS Gallery. And yet, inhabiting their tethers in the mono field also conjures the other end of the long-distance 15 kcl transmission, holding open the line for other receivers – a dense, overlay of differential geometries. Green Weather's linkless gambit, for example, conjures an earlier twentieth-century entanglement of telephony with telepathy,Footnote 32 twinned as both features and figures of a ‘pace of communication that was both more rapid and more efficient than that of language’.Footnote 33 Querying a physical process ramified, at both ends, as identical psychic contentFootnote 34 – in Green Weather's case, copacetic (or, just close enough) musical sensibilities – continues querying not only a gendered and racialized materialization of bodies but also their long-distance interimplication, conjugated between telephony's untimely timings and Amacher's ‘ALL TIME’ protocols. The tape – another (barely) veiled receiver, for this feed, with its hums, whirs and long silences – weaves these queries through another redoubling, another connective mise en scène.

* * *

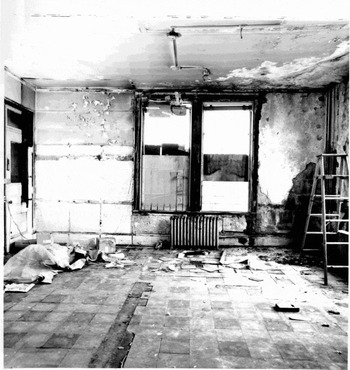

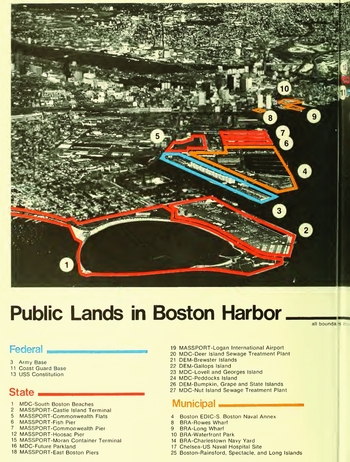

The City-Links #13 tape's gentle droplets and sighing vessels might evoke something like ‘ambient music’. But, like the leased line, the ‘encircling embrace’ of City-Links’s ambire also dissimulates a separation, an ‘ambi’ that both conjoins and distinguishes, like the two-sides-at-once of ‘ambivalent’ or ‘ambiguous’.Footnote 35 This tape's drips, drops, thuds, and thumps index its telephonic coupling, opposite Amacher's studio-side ReBVox, with a phone block and microphone mixer at the Pier.Footnote 36 Here. . . there. . . or both (but not quite): the crumbling walls, boarded windows, and torn-up floor capture an infrastructural neglect – a ‘modern gothic’ – that catch the Harbor careening amid not just economic change, but also economic change as a kind of social change that entails the obsolescence of the past (see Figure 3).Footnote 37 After the seaport's sharp decline during the 1960s, the Moran Terminal introduced container shipping to the region in 1971, initiating a massive resurgence of trade and reconfiguring ‘the Harbor's heterogenous patchwork of civic, state, and federal lands as a new prerogative for expansion and development that prioritized private shipping concerns’ (see Figures 4 and 5).Footnote 38 That same year – and two years before Amacher placed her microphone Pier-side – one of this tape's (many) institutional locations, MIT's Center for Advanced Visual Studies, had trained its environmental art focus on Harbor and Charles River-based projects, recruiting artists specifically to ‘revitalize the deteriorating river environs as a public open space’.Footnote 39 While abandoned infrastructure provoked debates about an ethics and politics of memorialization across a deindustrialized Midwest and (some of the) Northeast, Amacher's microphone catches the Pier amid a rearrangement of social tense whereby its contaminated water, floating debris, and rotting vessels could be newly narrated as horizons of both aesthetic and economic possibility.

Figure 3 Pier Six at the Boston Harbor. Courtesy of the Maryanne Amacher Archive.

Figure 4 Map of Public Lands in the Boston Harbor, 1978. Amacher's microphone was placed at State location #6, also known as ‘Fish Pier’.

Insofar as inhabiting the tape–telelink couplet has so very briefly tarried with the uneven sectoral dislocations transforming Amacher's Harbor, its two parts have placed my listening there (or here) somewhat differently, suggesting further, unlikely groupings of music practices that thread tape – and especially environmental field recording – with and against further long-distance experiments. In an expert reading of Luc Ferrari's Presque Rien (1968), Brian Kane discerns how the Dalmatian Coasts’s social sounds are ‘brought to audibility’ in and as a mix that redoubles the flat surface – tape – on which it was recorded; a flat mix, in other words, that cannot disavow precisely its recorded character.Footnote 40 Amacher's mono transmission, too, cannot dissimulate a ‘spatial imprint of site’. Her mix eschews soundscape's paradigms of verisimilitude and instead points back at the facticity of its transmission (not its recording) for a dense, holographic interleave of social geometries and conjugations conjured by the project's many different notions of long-distance, as this essay's final vignette will demonstrate.Footnote 41 Yet, the ‘almost nothing’ that hisses behind this writing is no closer to Presque Rien (1967–70) than to projects that resound ‘high-tech’, long-distance desires more explicitly. Lingering on tape, Alvin Lucier's North American Time Capsule (1967)Footnote 42 proffers the voices of the Brandeis University Chamber Chorus made ‘alien’, in and as the gurgling chatter, robotic irruptions, and beam-like tones of a vocoder in glitched-out ecstasy, hardware that frayed a path for compression, that political economic ‘recipe for fitting more calls on the line’.Footnote 43 And finally, getting on the phone at Billy Kluver's Evenings of Art and Technology, the John Cage of Variations VII placed calls on the public network – to sites a lot like Amacher's (the ASPCA, the 14th Street ConEd Plant, Luchow's Restaurant, for example) – and, leaving, the receiver off the hook at both sites aspired to the leased lines’ open, dedicated connection. In extant documentation, these calls are lost in a seething miasma of sine tones, Geiger counters, and other electronics.Footnote 44

If Lucier's glitched-out vocoder and EAT's specially rigged handsets suggest yet another weave-like scene, that scene might also query ‘fitting more calls on the line’ much differently: not only a US telephone network within which long-distance dialing's expanded spatial reach could supplant industry as a symbol of US imperial power amidst a ‘generalized insecurity about economic change’, but instead the high-tech embodiments that materialized – eyes, ears, fingertips, backs and shoulders – in and as the speed at which calls could be processed on computerized consoles.Footnote 45 In contrast, Amacher's Harbor tape convokes less genealogies of compression than telephone operators disciplined along gendered and racialized lines and deskilled amid switchboards’ computerized beginning in the early 1960s.

At once intimate and remote, the operator's body – ‘her voice, gestures and fatigue commingled with the message delivery system’ – had long been a fraught locus of discipline, desire, fantasy, and anxiety.Footnote 46 Indeed, between the early 1960s and mid-1970s, the music practices resounded above coincided with the introduction of new switching technologies, in the Bell system, whose twinned logics of deskilling and discipline reconfigured gendered and racialized spheres of work, as Venus Green's Race on the Line has richly shown.Footnote 47 On computerized consoles, Direct Distance Dialing drastically reduced the number of calls requiring operator assistance. Renamed the ‘service specialist’, the operator at the unprecedentedly fast console inhabited a harsh disciplinary enclosure: constant, controlled and repetitive movement, eye and ear strain, acute stress and extremely detailed manager surveillance, afforded by the console itself.Footnote 48 Continually restructuring fraught paths linking deskilling to automation, Green shows, new technology opened new opportunities – particular for African-American operators – only to close them through ‘computerization and occupational segregation’.Footnote 49 Lingering with Amacher's claim to ‘long distance music’ dramatizes broader genealogies concerning how ‘new technologies have historically designated what kinds of labour are considered replaceable and reproducible versus what kind of creative capacities remain vested with privileged populations and spaces of existence’.Footnote 50

* * *

Amacher plies much from the ‘almost nothing’ that's been hissing along behind this writing.Footnote 51 Her working notes cajole the Harbor's ‘inner melody’ onto the five-line stave. Poised between F♯s one and two octaves below middle C, these bass staves appear, scrawled, in notes for City-Links #7 (Chicago, 1974) and #10 (Minneapolis, 1974), suggesting a centricity for parts of the entire series, resounding in and as the Harbor tapes or perhaps, like ‘Green Weather’ lodged, in the series, securing connections that never quite coincide.Footnote 52 On the City-Links #13 tape, Blum reliably focalizes D♯, with an anacrustic fall from F♯, referencing the Harbor's F♯ ballast, but guiding it towards a vaporous, melancholic minor orientation.

Blum's contributions unfold, on this tape, within a delicate five-part symmetry. Blum is at the Pier with Amacher's microphone streaming the Harbor's mono nuances, as usual. Yet, Blum's improvised activity also opens the excerpt, on a different tape and in a different space. Here. . . or there. . . (but not quite), he plays very, very close to a stereo pair, as though to the mic, for the mic. Spongy-mouth sounds nestle in the left channel while whistles, breaths, tones, and flutter tonguing arch through the right, nearly redoubling the left-to-right arrangement of the mouth and then the hands across the instrument. Staked on Blum's comportment with the instrument, the stereo image dissolves after about five minutes into a mono expanse of hiss-filled stillness, as droplets, thuds and thumps creep across the telelink. A second cluster of bolder contributions from Blum coincides with sparse whirs of vessels and planes and then, like the first, gives way to another long, static interval.Footnote 53 The tape concludes with the Harbor, alone: pulsing multiphonics effloresce – almost glow – towards audibility, and then shear apart in and as the corrugated whir of machinery. Velvety hums become spit and sputter as vessels draw close to the mono mic. In and as this passage, smouldering low-mids resolve into texturized, metallic rotations. Wending in and out of the mono field, this fuzzy thirty-five minute excerpt feels balanced, composed.Footnote 54

From end to end, the excerpt makes a point-to-point connection of sorts, arching from Blum to Amacher, like the networked link along which her Harbor Feed streamed. The excerpt's opening gambit indexes Blum's remote location, but concludes by conjuring Amacher at the mixing board, the feed's (partially) veiled receiver. There, she is subtle. In this fifth and final interval, comprised exclusively of Harbor activity, levels remain consistent, she seems not to ride the potentiometers. And she intervenes only subtly in panning space, nudging approaching vessels from right to left, but no more than fifteen degrees from centre. If Blum is still on the Pier, he's not playing. And Amacher does not, again, reprise his stereo contributions in her edit.

* * *

Yes, this article often becomes too poetic with its experiments in hearing from the perspective of the tape–telelink couplet. Tacking restlessly between the standpoint of tape and that of the telelink and back again, this article has perhaps left more lines open – more differentially connective scenes – than it has drawn conclusions. These locational manoeuvres have dialogued, tacitly, with Haraway's 1983 provocation – a full three years after Amacher's last City-Links project: ‘there is no place for women in the integrated circuit’.Footnote 55 Maybe not a place, but rather unevenly overlaid geometries of difference, contestation, and complicity. And even that, well, depends. Broadly, the article's experimental, even wild contours retake this query as a project of feminist musicology, extending critical genealogies of ‘the body’ that have oriented the field since the 1990s with refocused attention – not just constitutive frameworks for life, labour, and creativity, but also their uneven distribution in and as 1970s US historical coordinates. Rather than a dispersal or dematerialization of the body, this article has tried to sound out what aspects of long-distance consubstantiality are implicated – and unevenly (in)audible – in different registers of aesthetic, technological, social, and political analysis. This writing effort moves towards articulating questions of social content, power, and resistance that have long been central to feminist musicology to an emerging sound art discourse – that often claims Amacher as an originary figure – struggling to extend its interpretive horizons towards the social, the cultural, and the political.

Like the tape hissing behind this article's many weave-like efforts, this effort, too, remains ongoing.