Social inequalities are ubiquitous in societies. People are unequal in every conceivable way and in endless circumstances, immediate as well as enduring, with respect to both objective criteria and subjective experiences. But what counts as social inequality? To date, there is no common understanding how the term social inequality can be defined. Although economic inequalities are relatively objective and therefore easier to identify, social inequalities encompass more than monetary resources. Individuals differ, for instance, in their access to voting rights, their freedom of speech and assembly, the extent of property rights, their access to education and their success in school and labor market, their health care, quality of housing, traveling, access to credit, occupational outlook and attainment, other social goods and services, and in their chances to achieve their individual goals. Thus, Kerbo (Reference Kerbo2011) recently proposed a definition of social inequality as ‘the condition where people have unequal access to valued resources, services, and positions in the society’ (p. 11). In light of this definition, it becomes clear that we are confronted with inequalities that are mutually intertwined with the relative position of individuals in a given society, that is, social stratification: power, class, status, money, and lifestyle.

Social stratification then refers to inequality insofar as it is not merely a matter of individual fortune, but rather inherent in prevailing forms of social relationships (Goldthorpe, Reference Goldthorpe2010) or inequality of opportunities (e.g., Shavit & Blossfeld, Reference Shavit and Blossfeld1993). The positions that individuals hold within social stratification are considered to be major determinants of their life-chances. In addition, the experience of inequality is not just objective, but also subjective and relational because it involves comparisons to others; for example, in terms of income, education levels, health outcomes, or social and political participation. People establish their own social position by comparing themselves to others, for example, to their neighbors, their friends, their gender, or former generations such as parents and grandparents (Runciman, Reference Runciman1972; Warwick-Booth, Reference Warwick-Booth2013). This could have an influence on how people subjectively perceive and understand social trajectories. In sum, social inequalities can be described in terms of individual differences in a variety of indicators and outcomes and can be recognized by an individual or group via comparison to others objectively and subjectively.

In the following, social inequality is defined as a generic term for a set of indicators that characterize the relative standing of individuals with respect to their capacity to consume or produce goods that are either generally valued in our society or by the individuals themselves. Within this approach, one might distinguish among different categories of valued assets and resources. In the recent inequality literature, as well as in political task forces and committees (e.g., Alkire, Reference Alkire2005; Cunha & Heckman, Reference Cunha and Heckman2009; Fowler & Schreiber, Reference Fowler and Schreiber2008; Giovannini et al., Reference Giovannini, Hall, Morrone and Ranuzzi2011; Lareau, Reference Lareau2002), several dimensions are discussed that should be assessed collectively when studying mechanisms of social inequalities. These dimensions not only include, for instance, skill formation and educational attainment, but also integration and participation in social and political life, as well as subjective perceptions of quality of life. People ‘scoring high’ on indicator variables related to these dimensions would be considered as relatively successful. In contrast, since failures and behaviors that are considered to go beyond the normal range are also indicators of social inequalities, the investigation of deviant behavior and behavioral problems provides further insight into this complex phenomenon.

In such a comprehensive framework, it is important to note that the considered indicators are not only valuable goods in their own right. Rather, most of them can also serve as functional resources that individuals can invest to achieve other desired goods in the future. For example, educational attainment can be seen as an investment into labor market outcomes later in life but can also be considered as a valuable goal itself. Another aspect of this approach addresses the individual experience of inequalities. Negative life events, such as, for instance, unemployment, can have long-lasting deleterious effects on subjective wellbeing (Headey, Reference Headey2010) given that losing one's job can be humiliating and extremely harmful to the health and social prestige of those affected. Apart from individual differences in the probability of experiencing the event of unemployment, there is also substantial variation across individuals in their reactivity to job loss, a fact that is not yet well understood (Bonanno, Reference Bonanno2004; Lucas, Reference Lucas2007). Hahn et al. (Reference Hahn, Specht, Gottschling and Spinath2015) provided first evidence that certain personality traits act as risk factors for individuals faced with a brief period of unemployment. Moreover, national inequality indices (e.g., income inequality and unemployment rate) have been shown to be negatively associated with wellbeing, a fact that could be explained by social relations such as status anxiety, social comparison, or economic worries (Oishi et al., Reference Oishi, Kesebir and Diener2011; Roth et al., Reference Roth, Hahn and Spinath2016; Welsch, Reference Welsch2007). It can also be expected that all these mechanisms influencing subjective quality of life are in part associated with genetic differences between individuals (Turkheimer, Reference Turkheimer2000). Therefore, a special focus should lie on possible interactions between personal characteristics and different situations across the life course by taking genetic confounds into account when the goal is to understand economic behavior and psychological wellbeing. Here, individual experiences are not only a result, but can also be a potential ingredient for the explanation of inequalities and can serve as strong motivating forces at all levels.

To explain mechanisms of social inequalities across the life span, several research disciplines have developed multiple approaches to investigate different aspects along the development and persistence of social inequalities by using corresponding methods. However, the majority of research in this field was limited in its ability to incorporate both multiple individual and social characteristics, as well as information on genetic influences to identify processes of social developments systematically.

Sociological Approaches to Social Inequality

A central goal of sociological research is to identify determinants of individual life courses and opportunities within and between populations. One of the major questions in sociological research addresses how society shapes the life course of its members. However, a theoretical problem arises, since the defined starting point in many approaches — that is, the individual — is already socially formed in terms of race, gender, and the family of origin to which the individual belongs. Thus, lifetime analyses, social stratification, and social mobility research tend to study associations between social origins, such as social class, socio-economic status (SES) or parental resources, and social outcomes of the individual — again, social class, welfare state, or career success (Erikson & Goldthorpe, Reference Erikson and Goldthorpe1992). Research can, by and large, be characterized by following differential pathways to success and failure over the life course while searching for specific characteristics within and outside the parental home that provide a child with good or bad chances in life.

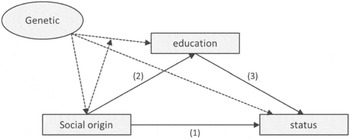

For instance, the status-attainment approach (for an overview, see Grusky et al., Reference Grusky, Ku and Szelényi2008) has become one of the most widely used theoretical perspectives in sociological research on social inequality and economic well-being. The basic status-attainment model comprises three paths: (1) the direct impact of social origin on occupational status, (2) the direct impact of social origin on education, and (3) the direct impact of education on occupational status, with (2) and (3) measuring the indirect effect of social origin on occupational status (see Figure 1). Studies in the tradition of this approach and other sociological research methods have typically investigated the extent to which the present occupational status of an individual can be explained by the occupational status of the family in which the person grew up, and in more recent studies, also considering the person's own educational attainment. Among the most robust findings of this research tradition are: (1) that social origins play an important role for educational and status attainment even though this effect tends to be less strong and varies across societies, (2) that effects are stronger at earlier than at later educational transitions, and (3) that education mediates a substantial part but not the full association between origins and destinations (Breen & Jonsson, Reference Breen and Jonsson2005; Breen et al., Reference Breen, Luijkx, Müller and Pollak2009; Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Goldthorpe and Mills2005).

FIGURE 1 Modified status attainment model.

One criticism of the status attainment approach is that even if all paths in the model were accurately specified, it remains unclear how, for example, social origins influence occupational status. Moreover, this model cannot explain if and why responses to societal influences are not homogenous, or at least contingent, among all individuals. In other words, the assumption of uniform causal effects is misleading (e.g., Abbott, Reference Abbott2001). Over the years, traditional research models have been extended in a number of ways, first and foremost by the Wisconsin model, which integrates interpersonal influences and aspirations as mediating mechanisms (e.g., Hauser et al., Reference Hauser, Warren, Huang, Carter, Arrow, Bowles and Durlauf2000; Heckman Reference Heckman2006).

Also, much classical psychological constructs such as the Big Five personality traits (Costa & McCrae, Reference Costa and McCrae1992) or aspects of self-concept and motivation have been included, showing strong associations to educational and academic achievement. There is growing evidence that non-cognitive skills, such as self-control and self-efficacy, may be as important as cognitive skills (Heckman & Kautz, Reference Heckman and Kautz2012; Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Abraham and Bond2012). Within the Five Factor model of personality, academic performance is most consistently associated with conscientiousness (Poropat, Reference Poropat2009), which is highly correlated with grit (Duckworth & Quinn, Reference Duckworth and Quinn2009). Moreover, externalizing psychopathology has consistently been associated with academic difficulties (Breslau et al., Reference Breslau, Michael, Nancy and Kessler2008; Esch et al., Reference Esch, Bocquet, Pull, Couffignal, Lehnert, Graas and Ansseau2014), as has poor emotion regulation (Ivcevic & Brackett, Reference Ivcevic and Brackett2014).

Nevertheless, even with relatively comprehensive measurements and an inclusion of psychological mechanisms, the overall impact of social origins and individual characteristics on individual success and failure is still not fully understood. This could be due to the fact that both individual as well as social factors may be biased by unmeasured confounds (Jencks & Tach Reference Jencks, Tach, Morgan, Grusky and Fields2006; Smeeding et al., Reference Smeeding, Erikson, Jäntti, Smeeding, Erikson and Jäntti2011). Modeling patterns of life-course events as well as social mobility by using the individual and its social background as starting point neglects that individuals already differ with respect to their genetic makeup from the very start and that they react differently to environmental conditions based on genetic disparity (Pinker, Reference Pinker2003; Polderman et al., Reference Polderman, Benyamin, De Leeuw, Sullivan, Van Bochoven, Visscher and Posthuma2015; Scarr, Reference Scarr1992, Reference Scarr1993; Visscher et al., Reference Visscher, Brown, McCarthy and Jang2012).

Genetic variation is obviously a major source of individual differences in various life outcomes, but also of differences in how individuals react to social conditions that, if unconsidered, lead not only to less complete but also to less precise explanations. The individual genetic makeup (i.e., genotype) exists prior to individual social influences and may affect social inequality due to genetic variation. However, the unfolding of the genotype depends on environmental opportunities (Scarr, Reference Scarr1992, Reference Scarr1993). Thus, both genetic and environmental sources shape people's rankings in the system of social inequalities. As a consequence, indicators of social origin are not the only starting point in life, as assumed in the status attainment model, but are rather part of the social structuring of life chances. In fact, it can be assumed that the measured impact of ascribed characteristics and positions, like the attributes of the family of origin are, to a certain degree, influenced by genetic factors (as illustrated in Figure 1). This involves considering that supposed environmental contributions are in part active via genetic factors and consequently genetic and social inheritance should be distinguished.

Quantitative Behavioral Genetics

Decades of behavioral genetic research have shown that the vast majority of individual-level variables are influenced by both genetic as well as environmental factors (for a review, see Polderman et al., Reference Polderman, Benyamin, De Leeuw, Sullivan, Van Bochoven, Visscher and Posthuma2015; Turkheimer, Reference Turkheimer2000). The fact that genetic influences play a crucial role in explaining individual differences does not only apply to ‘proximal’ characteristics and behavioral outcomes like health and personality, but also includes more ‘distal’ ones, such as education, demographic events, and social inequalities (e.g., Guo & Stearns, Reference Guo and Stearns2002; Turkheimer, Reference Turkheimer2000). Moreover, it is logical and at the same time empirically proven that whole genome effects do not necessarily become smaller as we move from psychological traits to actions and outcomes (Freese, Reference Freese2008). In behavioral genetic research, the question of ‘how much’ of the variance genetic versus environmental factors explain has already been replaced by studies of the processes that mediate the relation between the genome and the social phenomenon of interest. However, existing behavioral genetic studies suffer from not making full use of the sociological life-course perspective and from not having enough cases to follow the complicated patterns of genome-environment interactions. Moreover, most studies do not consider specific social factors over time to explain broader social phenomena and are often either restricted to certain topics (mostly concentrating on health or behavioral disorders), or to a specific age range.

To overcome these shortcomings of previous research attempts and to rigorously study sources of social inequalities with respect to genetic and environmental influences, at least three important issues should be noted.

First, the effect of genes could depend on the environment and/or the effect of the environment could depend on the genotype (Plomin et al., Reference Plomin, DeFries, McClearn and McGuffin2008). Such patterns are designated as gene-environment interactions (G×E), that is, the moderation of genetic predispositions by environmental experiences or, in other words, the genetic sensitivity to environmental influences. However, simple quantitative genetic models average heritability estimations over any group differences (e.g., differing SES) within a population, although this is not an adequate approach in the light of the growing evidence for G×E. In order to disentangle these complex patterns of the gene-environment interplay, the following aspects have to be taken into account to transform a mere statistical association between genome and outcome into an explanation based on a chain of interlinking causal factors (e.g., Freese, Reference Freese2008; Kendler, Reference Kendler2001; Rutter et al., Reference Rutter, Pickles, Murray and Eaves2001; Shanahan et al., Reference Shanahan, Hofer, Shanahan, Mortimer and Shanahan2003): (1) biological and/or psychological processes have to be measured appropriately to elucidate the path from the genome to behavioral outcomes. Given that social influences at the level of individual attributes alone are confounded by influences of the social environment and individual reactions to them, various levels of contextual influences need to be measured. (2) To understand how social situations and circumstances influence genetic expression requires examining biographical developments and the accumulation of life experiences. (3) Heritability estimates of outcomes do not only characterize a population (or sample) of individuals but also constitute properties of social systems that reflect the extent to which genetic variation in that system influences individual outcomes.

Second, behavioral genetic studies of social inequalities need to address and evaluate the question whether estimates of environmental influence derived from genetically informative samples apply to the general population (Rutter et al., Reference Rutter, Pickles, Murray and Eaves2001). According to Farber (Reference Farber1981), it is disputable whether any sample of twins can actually be representative for the population, because of inherent factors of the twin existence, such as a different family structure or the shared prenatal environment. Although twin-versus-singleton comparisons have not yielded differences in the prevalence rates regarding characteristics of antisocial behavior or antisocial personality traits (Gjone & Nøvik, Reference Gjone and Nøvik1995), it remains an open question whether this also applies for other psychological and sociological factors and mechanisms. To increase the generalizability of the results, a stringent behavioral genetic study of social inequalities needs to ensure that the twin (family) sample under study is representative for the population of interest.

Third, to identify specific environmental effects on social inequalities, a broad sampling of measured ‘environmental’ variables is required that allows the aggregation of measures to test for interactions among environmental variables, and to study stability and change of environmental factors over time. Since environmental effects include more than just environment shared or non-shared by twins, research designs that comprise not only twins but also significant interaction partners (parents, non-twin siblings, and partners) as target individuals (and not only as raters providing information about twins) are especially promising, because it provides a wealth of measures of the social environment. Moreover, to study environmental effects, gene-environment correlations (rGE), and G×E, the full variation of any given environmental factor should be covered.

Integrating Sociological Approaches and Quantitative Behavioral Genetics

To explain the development of social inequalities over the life course, it is crucial to understand how genetic heterogeneity is attended to ‘by society’ and translated into advantages or disadvantages in the first place, and when and under which circumstances the expression of biological dispositions may be enhanced or restricted by environmental influences. To test whether a putative environmental variable really affects behavior environmentally, designs that are able to control for genetic influences are indispensable.

Over the last years, studies have increasingly focused on the interplay between genes and the environment. This development has been driven by the rapid advances in molecular genetics as well as the methodological advances that facilitate the possibility to analyze moderation using twin designs (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, McClay, Moffitt, Mill, Martin, Craig and Poulton2002; Plomin & Crabbe, Reference Plomin and Crabbe2000; Purcell, Reference Purcell2002). These advances have led to a growing number of genetically informed studies that have included measures of environmental factors to their designs. The coupling of well measured environment and a genetically informed design can provide a good starting point to advance our understanding of gene-environment interplay.

For example, Conley et al. (Reference Conley, Domingue, Cesarini, Dawes, Rietveld and Boardman2015) investigated the relation between parental and offspring education. To understand whether the estimated social influence of parental education on offspring education is biased or moderated by genetic inheritance, they used findings from a recent, large genome-wide association study on educational attainment to derive an individual genetic score to predict educational attainment. Using data from two independent samples, this genetic score significantly predicted years of schooling in both between-family and within-family analyses. Furthermore, the phenotypic parent-child correlations in education could be split into one-sixth genetic transmission and five-sixths social inheritance. Conditional on the child's genetic score, the parental genetic score had no significant relationship to the child's educational attainment. Finally, measured socio-demographic variables at the parental level moderated the effects of offspring's genotype, providing evidence for the importance and interplay of both genetic and social inheritance.

Also, a number of quantitative G×E interaction studies investigated the effect of the family environment on the heritability of intelligence (Rowe et al., Reference Rowe, Jacobson and Van den Oord1999; Scarr-Salapatek, Reference Scarr-Salapatek1971; Tucker-Drob & Bates, Reference Tucker-Drob and Bates2016; Tucker-Drob et al., Reference Tucker-Drob, Rhemtulla, Harden, Turkheimer and Fask2011; Turkheimer et al., Reference Turkheimer, Haley, Waldron, d'Onofrio and Gottesman2003). The results of these studies suggested that parental education and other socio-economic indicators of the family can modify the relative contribution of genetic and environmental effects on individual differences in intelligence. In U.S. samples, for example, genetic effects on intelligence were stronger in families with higher SES compared to lower SES families. In other words, environmental factors influencing intelligence were more important at the lower end of the SES distribution. In sum, Tucker-Drob and Bates (Reference Tucker-Drob and Bates2016) found that the magnitude to which these factors of the family environment moderate genetic and environmental influences on intelligence differs across nations, indicating ‘that Gene × SES effects are not uniform but can rather take positive, zero, and even negative values depending on factors that differ at the national level’ (p. 10). Also, many studies have begun to summarize effects of G×E across multiple studies systematically and quantitatively regarding a variety of phenotypes. For example, Byrd and Manuck (Reference Byrd and Manuck2014) showed in a meta-analysis that MAOA variation (i.e., variation in the gene encoding monoamine oxidase-A) moderates effects of early life adversity (e.g., physical and sexual abuse, harsh discipline, neglect, or assault) on male subjects’ aggressive and anti-social behaviors.

To further integrate sociological and behavior genetic research approaches and to overcome the aforementioned shortcomings of existing studies, the German twin family study ‘TwinLife’ was launched in 2013 to examine various mechanisms of genetic and environmental factors involved in the development of social inequalities. By means of the TwinLife study, more specific research questions such as ‘What are the shaping environmental resources enhancing genetic potential for behavioral characteristics related to success in school?’ or ‘To what extent do early institutional environmental circumstances influence the life course in dependence of our genetic makeup?’ can be investigated.

The TwinLife Study

TwinLife is an interdisciplinary project that combines the perspectives of psychological and sociological theories and research with behavioral genetic methodology. The goal of TwinLife is to examine the interplay between genetic and environmental mechanisms that shape, promote, and inhibit social inequalities over the life course. TwinLife integrates the know-how of these different research disciplines to investigate the development of social inequalities by taking into account psychological as well as social mechanisms, their genetic origin, and the interaction and covariation between 429 these factors. Therefore, a quantitative behavioral genetic research design was applied to assess the relative contributions of genetic and environmental factors in observable phenotypic variation by comparing the phenotypic similarity in relatives with known (and different) average degrees of genetic relatedness. One of the major goals of TwinLife is to study how and at which environmental state genes and environments shape individual life courses, and to identify covariation and interaction of genetic and environmental sources in a longitudinal design. Furthermore, by measuring familial and individual environmental factors, it becomes feasible to identify specific environmental characteristics within and between families that may explain causes of social inequalities. Using genetically informative data allows us to control statistically for genetic influences to identify ‘true’ environmental factors that exert a direct effect on success and failure in life. On the other hand, TwinLife can be leveraged to understand under which circumstances ‘environmental’ constructs are influenced by individuals via their genetically influenced characteristic. This approach may help to guide sociopolitical interventions such as strategies for remediating and family investment in sensitive periods (Cunha & Heckman, Reference Cunha and Heckman2009). Derived from the statements above, TwinLife was designed to address the following four key issues:

-

1. TwinLife adopts a multidimensional perspective on social inequalities, including inequalities in different major life domains. Therefore, social inequality is considered as a multi-dimensional construct comprising a variety of indicators that characterize the relative standing of individuals in our society. We explicitly distinguish between subjective and more objective dimensions of inequality (Stiglitz et al., Reference Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi2010) and measure a broad range of psychological characteristics to capture the variety of individual heterogeneity for the interplay between individuals and society.

-

2. Twinlife investigates developmental trajectories across childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood in a longitudinal design. Through the implementation of a cross-sequential design, twins from four different age groups (5, 11, 17, and 23 years at the first measurement occasion) are examined repeatedly. Assessment begins shortly before school enrollment in the youngest group and ceases when most of the career-related decisions are completed in the oldest group.

-

3. Furthermore, the Extended Twin Family Design (ETFD) applied in TwinLife is conceptualized in accordance to the Nuclear Twin Family Design (NTFD; Heath et al., Reference Heath, Kendler, Eaves and Markell1985), comprising first-degree relatives of same-sex monozygotic and dizygotic twins, but extended by the inclusion of step-family members as well as partners and spouses in case the twins having reached a certain age. This extension aims at providing a richer assessment of the environment in which the twins grow up and live including important social interactions.

-

4. Finally, TwinLife explicitly aims at capturing a large variation of behavior and environmental factors in a representative sample of twin families. The quantification of environmental effects – those shared within families as well as those not shared – is a central concern. Both the substantial number of participants realized in an ETFD and the representative variation of the environment make it feasible to overcome shortcomings in existing genetically informative studies and, in particular, to more adequately take genetic information into account to identify environmental factors that exert an effect on success and failure in life.

Multidimensional Perspective on Social Inequalities

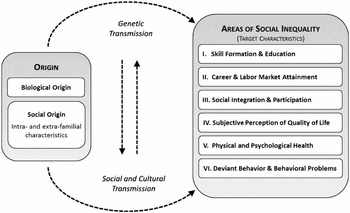

The focus of TwinLife is on the development of social inequality over the life course, including genetic, social, and psychological factors shaping social inequalities within and between families. The set of measurements reflects this focus by assessing six broad categories of constructs: (1) skill formation and education, (2) career and labor market attainment, (3) social integration and participation, (4) subjective perception of quality of life, (5) physical and psychological health, as well as (6) deviant behavior and behavioral problems (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 Main focus of TwinLife.

The selection of these six inequality domains was based on their prominence in the inequality literature (e.g., Alkire, Reference Alkire2005; Cunha & Heckman, Reference Cunha and Heckman2009; Fowler & Schreiber, Reference Fowler and Schreiber2008; Lareau, Reference Lareau2002) as well as on their potential meaning for mechanisms involved in the development of social inequalities. These domains are also featured in recent discussions and task forces on social inequality (e.g., Giovannini et al., Reference Giovannini, Hall, Morrone and Ranuzzi2011).

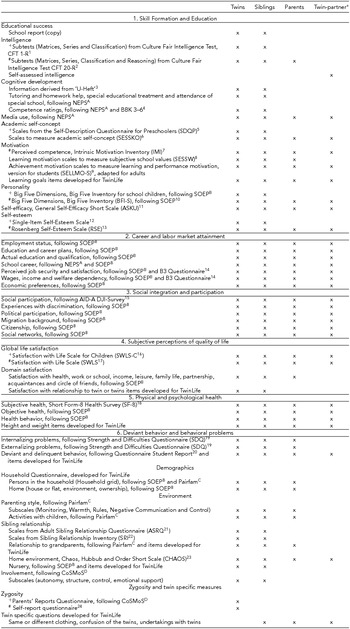

To cover a broad range of putative environmental influences, TwinLife comprises a large set of age- and domain-specific environmental measures as well as demographic measures and aspects of the twin situation. The complete survey program assessed within the first in-house interview of the first wave is presented in Table 1.Footnote 1 In some cases, respondents answer questions about both, themselves, and about other family members. In particular, parents report on their own characteristics and also on their children's characteristics when the twins or siblings are too young to complete self-reports. For 328 participating twin pairs, we also collected DNA samples in order to validate the zygosity determination using physical similarity ratings in the three underaged cohorts (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Busjahn, Faulhaber, Bähring, Robertson, Schuster and Luft1997; Oniszczenko et al., Reference Oniszczenko, Angleitner, Strelau and Angert1993; Price et al., Reference Price, Freeman, Craig, Petrill, Ebersole and Plomin2000).

TABLE 1 Summary of Measures Included in TwinLife

Constructs were sometimes measured over parent ratings, especially for younger children; *Partners outside the twins’ household were assessed by using a short version of the questionnaire program, and partners living in the twins’ household were assessed with the full questionnaire program; A = NEPS: National Educational Panel Study (Blossfeld et al., Reference Blossfeld, von Maurice and Schneider2011); B = SOEP: Socio-Economic Panel (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Frick and Schupp2007); C = Pairfam: Panel Analysis of Intimate Relationships and Family Dynamics (Huinink et al., Reference Huinink, Brüderl, Nauck, Walper, Castiglioni and Feldhaus2011); D = CoSMoS: German Twin Study on Cognitive Ability, Self-Reported Motivation, and School Achievement (Hahn et al., Reference Hahn, Gottschling and Spinath2013); +Instrument for young children; #Instrument for adolescents and adults; 1CFT1-R: Culture Fair Test, Grundintelligenztestskala 1-Revision (Weiß & Osterland, Reference Weiß and Osterland2013); 2CFT20-R: Culture Fair Test, Grundintelligenztest Skala 2- Revision (Kuhn et al., Reference Kuhn, Holling and Freund2008); 3The ‘u-Heft’ is an examination record, which documents the results of nine medical check-ups from birth to school-age; 4Interviewer rating, BBK 3–6: Beobachtungsbogen für 3- bis 6-jährige Kinder (Frey et al., Reference Frey, Althaus and Duhm2008); 5SDQP: Self-Description Questionnaire for Preschoolers (Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Ellis and Craven2002); 6SESSKO: Skalen zur Erfassung des schulischen Selbstkonzepts (Dickhäuser et al., Reference Dickhäuser, Schöne, Spinath and Stiensmeier-Pelster2002); 7IMI: Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (McAuley et al., Reference McAuley, Duncan and Tammen1989); 8SESSW: Skala zur Erfassung subjektiver schulischer Werte (Steinmayr & Spinath, Reference Steinmayr and Spinath2010); 9SELLMO-S: Skalen zur Erfassung der Lern- und Leistungsmotivation – Version für SchülerInnen (Spinath et al., Reference Spinath, Stiensmeier-Pelster, Schöne and Dickhäuser2002); 10BFI-S: Big FiveInventory, form S (Gerlitz & Schupp, Reference Gerlitz and Schupp2005); 11ASKU: Allgemeine Selbstwirksamkeit Kurzskala (Beierlein et al., Reference Beierlein, Kovaleva, Kemper and Rammstedt2012); Single-Item Self-Esteem Scale (Robins et al., Reference Robins, Hendin and Trzesniewski2001); 13RSE: Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg1965); 14B3 Questionnaire (Abendroth et al., Reference Abendroth, Melzer, Jacobebbinghaus and Schlechter2014); 15AID:A – DJI-Survey: Aufwachsen in Deutschland – Alltagswelten, Deutsches Jugendinstitut (2009); 16SWLS-C: Satisfaction with Life Scale adapted for Children (Gadermann et al., Reference Gadermann, Schonert-Reichl and Zumbo2010); 17SWLS: Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin1985); 18SF-8: Short Form-8 Health Survey (Ellert et al., Reference Ellert, Lampert and Ravens-Sieberer2005); 19SDQ: Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, Reference Goodman1997); 20Fragebogen Schülerbefragung Dortmund 2012: SFB Bielefeld (Reinecke et al., Reference Reinecke, Stemmler, Sünkel, Schepers, Weiss, Arnis and Wittenberg2013); 21ASRQ: Adult Sibling Relationship Questionnaire (Heyeres, Reference Heyeres2006); 22SRI: Sibling Relationship Inventory (Boer et al., Reference Boer, Westenberg, McHale, Updegraff and Stocker1997); 23CHAOS: Chaos, Hubbub and Order Short Scale, six-item version (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Deater-Deckard, Petrill and Thompson2012); 24Self-report questionnaire (Oniszczenko et al., Reference Oniszczenko, Angleitner, Strelau and Angert1993).

A wide array of psychological constructs was included in TwinLife to examine developmental paths in the aforementioned domains of social inequality. Thus, the possible contribution of, for instance, motivation, (non-)cognitive skills, and personality characteristics over the life course can be studied simultaneously with sociological constructs. Apart from this, TwinLife puts a special focus on environmental factors and developmental tasks that become relevant in different phases of personality and competency development over the life course (i.e., early childhood, adolescence, early and middle adulthood). In this respect, we did not only measure the occurrence of various life events, but also assessed how persons subjectively evaluate emerging tasks in school and job life, romantic relationships, family life, social life, and physical changes.

This research program was established by taking existing panel studies in Germany (e.g., Pairfam, SOEP, and NEPS) and beyond (e.g., TEDS and Add Health) into account to assess measures for selected explanatory and outcome factors with a potential for cross-study comparisons. More precisely, we used partly the same or similar operationalizations of core constructs to create the synergetic potential as well as the possibility for extended analyses with independent samples. Linking our research program to other large-scale panel studies enhances the power for causal inference for several interdisciplinary research questions in the field of life chances.

Cross-Sequential Design

Longitudinal studies with a focus on the measurement of environmental characteristics are required to study social inequality as a life-course phenomenon. Moreover, the investigation of multiple cohorts over time (i.e., the cross-sequential design) allows us to overcome shortcomings inherent in cross-sectional age group comparisons. Therefore, TwinLife follows the development of four cohorts of same-sex twins and their families.

For the first measurement occasion, families were invited to take part in the study when the twins were 5, 11, 17, and 23 years old. Each of the four age cohorts was derived from birth cohorts spanning 2 years,Footnote 2 resulting in about 1,000 twin families in each cohort (500 per birth year) and a total of approximately 4,000 twin families when the first assessment will be completed. To assess each twin family within the same cohort at about the same age, each wave is organized into two half-waves, each half following the respective birth cohort of twins. The first wave of the TwinLife study comprises a more extensive face-to-face interview with all family members chosen in the participants' homes (see Table 1 for an overview of instruments) and a telephone interview. A shorter telephone interview takes place 1 year after the home interviews. Apart from follow-up questions on the current living situation, education and work situation, new information and constructs that were not captured in the previous face-to-face interviews are also assessed (e.g., self-regulation, religion, life events, and life transitions). Due to the cross-sequential design, and given the planned total duration of 8 years of assessments, TwinLife will cover an age range from 5 years of age (youngest cohort at measurement point 1) to an age of 31 (oldest cohort at the last measurement). Altogether, five face-to-face interviews in the participants’ homes and four telephone interviews in the years in between are envisaged. Thus, our measurement starts before children enter primary school and ends when most young adults have decided on their career.

Important transitions with a key function for developmental pathways (e.g., from pre-school to school and from primary school to secondary school) tend to occur between the first and second measurement occasions. The sample size of 1,000 same-sex twin pairs in each cohort provides increased statistical power for implementing G×E and rGE in our analyses (see Narusyte et al., Reference Narusyte, Neiderhiser, D'Onofrio, Reiss, Spotts, Ganiban and Lichtenstein2008; Purcell, Reference Purcell2002).

In the further course of the study, we will define several criteria following the twin families throughout the study. Although this will increase the complexity of our data structure, divorce and separation of parents as well as one or more persons moving into the twins’ household constitute important experiences and will therefore be captured in our study. Biological parents and biological (half-) siblings who leave the original household will also be followed and further assessed. We intend to follow non-biological parents or siblings only if they stay in close contact with the twins, because members of these groups can only exert an environmental influence on the twins. For economic reasons, data from persons not living in the twins’ household was and will be collected by mail, telephone, or through online assessment whenever possible at the same measurement times planned for persons living in the twins’ household, thus, not hampering the quality of the data.

Extended Twin Family Design

The original NTFD was applied in a modified form as the focus not only lies on the twins and their biological relatives, but also on the family in which the twins were raised, thus, also including step-family members and the twins’ partners. If it was the case that the twins grew up in a step-family or some kind of blended family, data collection also comprised step-family members (e.g., stepfather or half-sibling) when they were living in the same household as the twins. In these cases, the biological parents living outside the household were also asked to participate in the study. In this way, we ensure covering environmental as well as genetic influences passed on from parents to their children. We also included half-, step-, and adoptive-siblings, but given the restriction of only one additional sibling per twin pair, the sibling with the highest degree of genetic relatedness and the smallest age difference to the twins was preferred. Furthermore, when the twins have reached a certain age (cohort 4), partners or spouses are included in the measurement because they may represent an important aspect of the environment. In addition, their inclusion sheds light on the sources of spouse similarity (e.g., phenotypic assortment and social homogamy) and its contribution to individual differences and thus to social inequality (e.g., Kandler et al., Reference Kandler, Bleidorn and Riemann2012).

This ETFD offers several advantages over the classical twin design (CTD; e.g., Eaves, Reference Eaves2009) since the CTD is based on some restrictive assumptions that are not always met for a phenotype under study (e.g., negligible non-additive genetic effects or the absence of assortative mating). Although the CTD provides reasonably accurate estimates of broad heritability (Coventry & Keller, Reference Coventry and Keller2005; Hahn et al., Reference Hahn, Spinath, Siedler, Wagner, Schupp and Kandler2012), extended designs can provide estimates of non-additive effects in the presence of environmental effects shared within families such as vertical transmission (i.e., non-genetic factors shared by parents and offspring) or sibling effects (i.e., non-genetic factors shared between siblings and twins but not between parents and offspring). They consider assortative mating and social background factors shared by siblings, parents, and spouses of twins. They also allow for more specific analyses of environmental effects shared by family members, such as twin-specific, sibling-specific, and spouse-specific shared influences (Keller et al., Reference Keller, Medland, Duncan, Hatemi, Neale, Maes and Eaves2009).

Representative Sample

One of the primary tasks for the first wave of TwinLife was the assurance of a sample that proportionally reflects key characteristics of families in all four cohorts. To establish a representative (twin family) sample on the one hand, and to cover a large range of behavior and environments on the other hand, we implemented a sophisticated sampling procedure that includes a proportional ‘basic sample’ as well as additional samples of large municipalities (50,000 or more inhabitants) and rural regions (5,000 to under 20,000 inhabitants). Given that a central twin register is not available in Germany, twins were identified through local registration offices. Identified twin families were first contacted via mail and informed about the study. Within a couple of days after this first contact, trained interviewers visited the families at home to establish personal contact to the families, provide further information about TwinLife, and ask whether the families were interested in participating. The main focus of our strategy was to realize an unbiased sample with respect to the twins’ families SES and the twins’ sex. As we are also interested in economic information of non-responders in comparison to responders, we asked for assumed zygosity, number of siblings, sex, and SES at the initial contact at home.

Sample Description

The first wave of TwinLife was organized in two ‘half waves’. By the end of 2015, the first half of the sample had completed the first in-house, face-to-face interview. In total, 2,009 twin families comprising 8,116 individuals living in 2,422 households were interviewed. Twin families were drawn from German communities of at least 5,000 inhabitants across all federal states. Participation of twin families consisting of at least both twins and one biological parent differed between cohorts: In the youngest three cohorts 45–47% of the gross sample (a random sample drawn from resident registers) agreed to participate. In the oldest age cohort, this was achieved in 23% of the gross sample of twin families.

One reason for the lower participation rate of this cohort is that in these families the respondents required to establish a valid case often live in different households and are therefore not as easily accessible as families in the younger birth cohorts. However, an overall response rate of 37% could be considered as satisfactory and comparable to other German twin studies (Spinath & Wolf, Reference Spinath and Wolf2006). A participation rate of this level is generally not achieved in Germany during general population surveys and thus represents a good result, especially in the light of the extensive volume of the interviews. Besides the twins, especially their biological mothers showed a high willingness to participate in the survey (97%, biological fathers: 77%). In families with a sibling at survey age (5 years and older), this sibling participated in 93% of the cases. In 72% of the surveyed families, a complete case including the biological parents and, if present, the step-parent, sibling, and partners of the twins could be realized. With respect to the following telephone interview within the longitudinal design, the willingness to be interviewed again was exceptionally high (about 95%), which provides the basis for a stable twin family panel. For more details on the structure of the sample, see Table 2.

TABLE 2 Overview of the Net Sample of the First Half of TwinLife

In the first half of the sample that has been collected so far, about 45% (approx. 900 cases) of the same-sex twin pairs are male and 55% (approx. 1,100 cases) are female. Zygosity of the twin pairs was balanced across all cohorts, with 46% monozygotic (MZ) and 54% dizygotic twin (DZ) pairs. In detail, the sample included 216 MZ pairs (43%) in the youngest cohort, 204 (40%) in the second cohort, 254 (48%) in the third, and 255 MZ pairs (53%) in the oldest cohort. The sample represents the whole range of typically investigated socio-economic backgrounds. Hence, the sample facilitates socio-structural differentiated genotype sensitive analyses.

In the first half of the TwinLife data, we did not find the ‘middle class bias’ — overrepresentation of medium SES groups — often present in general population surveys. However, given the current sample, families with lower occupational status and no or lower secondary education are slightly under-represented compared to the socio-economic structure of similar twin and non-twin families in the German population. To further improve data quality and to reach a more accurate representation of each occupational status for the full sample of the first wave of face-to-face interviews, additional recruitment strategies with respect to families with lower socio-economic background were set for the second half of the sample.

Future Directions

The main task for the following periods will be to establish more waves of data collection and to realize a longitudinal design covering longer trajectories and more than one life period linked by various types of transitions. In addition to this task, we plan to include molecular genetic data into our analyses. DNA samples will not be collected before the third measurement occasion for two reasons: first, we wanted to minimize panel attrition in the critical early stages, as it was demonstrated in pre-test studies of other surveys that almost 20% of panel participants adamantly refuse to provide saliva. We expected that the increased level of trust between interviewer and interviewee after having participated in the study for some time will increase the participation rate.

Second, since molecular genetics is a rapidly evolving field, we expect the emergence of both improved statistical procedures and more closely spaced genetic markers, as well as an improved understanding of the genetic and evolutionary mechanisms involved in the heritability of complex traits (e.g., concerning gene expression and epigenetics) over the next 5 years.

A satellite project, ‘Early Childhood Education and Care Quality and Child Development: an Extension Study of Twins’, was first launched to seize the opportunity that for the youngest cohort, independent information about day-care centers as an important part of the environment could be collected. This project is a co-operation of Martin Diewald, Katharina Spieß, and Pia Schober, funded by the Jacobs Foundation. Parents of the youngest cohort were asked to give the interviewer the name and address of the day-care centers of the twins. The respective center will now be contacted, and both the manager of the day-care institution and the kindergarten worker directly responsible for the twins’ group will be interviewed about quality measures, structural conditions, and specific measures in the day-care center. Other satellite projects could focus on rather extensive studies on biological mechanisms linking the genome to social behaviors and outcomes, and use a sub-sample of TwinLife for this. Studies investigating genetic and biological mechanisms in great detail but with a small and non-random sample could use TwinLife as a reference study to check in which respects respondents differ from a representative sample.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation awarded to Martin Diewald (DI 759/11-1), Rainer Riemann (RI 595/8-1), and Frank M. Spinath (SP 610/6-1). The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.