At first sight, York should not be selected as a case-study of civic administrative literacy prior to the late fourteenth century. Compared with many English towns, fewer of York’s civic records before the 1370s have survived. G.H. Martin believed that York was not one of the English towns with surviving civic records from before 1300.Footnote 1 This comment was partially disproved by the subsequent discovery of a civic roll dated c. 1284.Footnote 2 However, it is still believed that the production of civic records in York was limited until the last quarter of the fourteenth century, and that York’s political culture relied more on orality than on literacy for a longer period than was true in London.Footnote 3

In an attempt to challenge this prevailing perception, this article proposes that York initiated the practice of record-keeping during the late thirteenth century, and that the compilation of records in the fourteenth century relied on earlier precedent. Before turning attention to York in particular, it is essential to first explain why this article has chosen record-keeping as the perspective for researching civic administrative literacy. Previous research on civic administrative literacy has adopted diverse approaches, such as studying the spaces where records were preserved, the professionals who managed records and the transcription of records.Footnote 4 As the subsequent discussion will show, record-keeping was a significant step in the growth of civic administrative literacy.

Martin attributed the preservation of civic records to administrative autonomy. By examining surviving records from English towns, Martin argued that by the second half of the twelfth century, towns were not significantly lagging behind royal or ecclesiastical institutions in creating and maintaining records.Footnote 5 While civic records before the thirteenth century are rare, Martin believed that this scarcity is due to the loss of most early records.Footnote 6 Before the practice of electing civic officials, civic communities were typically led by guilds. Consequently, the earliest surviving records in English boroughs are guild rolls, which deal with matters of ‘membership and status, as well as naturally with finance’.Footnote 7 Martin’s work is inspiring, but he overlooked the possibility that orality continued to play a significant role in society even after the introduction of written records. Documents were not inherently more trustworthy than memory itself. The loss of records did not necessarily undermine the functioning of civic administration, so the question arises: why should records be preserved?

Brigitte Bedos-Rezak made important advancements to the history of record-keeping in her study of northern French towns. She argued that the primary motivation behind preserving records was to ensure the trustworthiness of other documents issued by civic administration. In the twelfth century, civic records were memoranda of transactions witnessed in the city court. In the thirteenth century, a new form of record emerged, known as the chirograph, where multiple copies of a text were made and each party could receive an identical copy. The authenticity of other copies could be verified by comparing them with the copy deposited in the civic archives.Footnote 8 Bedos-Rezak highlighted that there were two crucial stages in the development of civic administrative literacy: record-making and record preservation. The transition from creating records to keeping them marked a significant milestone in the advancement of civic administrative literacy, and this transition took a considerable amount of time.

The distinction between the creation and preservation of records has been accepted by other historians. For instance, a recent definition of civic administrative literacy states that it is ‘the capacity of urban governments to generate both records and archives as part of their process of self-government’.Footnote 9 Katalin Szende expanded on Bedos-Rezak’s ideas by explaining how trust in civic administrative literacy developed in Hungarian towns. Szende proposed five distinctive chronological steps: (1) a town gaining the franchise of self-government; (2) the issuing of civic documents; (3) the institution of a town clerk; (4) the compilation of civic registers and the use of vernacular languages; and (5) the foundation of civic archives.Footnote 10 The establishment of an archive represented the final step in ensuring the reliability of civic records. Decades elapsed between the creation of the earliest records and the establishment of archives, illustrating that the growth of civic administrative literacy was a gradual process. When civic records started to be created, record-keeping did not immediately follow. The limited survival of civic records was not necessarily the result of the unfortunate loss and destruction of an archive but rather the lack of intention to securely preserve records.

The initiation of record-keeping is a milestone in the development of civic administrative literacy. Thus, it is necessary to explore when cities began to preserve records and also, if possible, to analyse the motives driving such preservation efforts. Proposing that the preservation of the English royal archives commenced in the late twelfth century, Michael Clanchy suggested the prominent role of Hubert Walter in this innovation.Footnote 11 By contrast, the scarcity of sources poses formidable challenges to pinpointing the precise emergence of urban archives. Urban historians have often speculated that the development of civic administrative literacy was influenced by other institutions, particularly the church and the royal government.Footnote 12 Ecclesiastical and royal institutions, established earlier than civic bureaucracies, began using administrative documents before their urban counterparts. These external factors were admitted by historians studying York as well.Footnote 13 This article does not seek to establish which influence, whether from the church or the royal government, holds greater significance. Rather, it aims to concentrate more on the influence of the royal government. The ‘crown–town’ relationship in late medieval England has attracted considerable attention from urban historians in recent years, which has served as an inspiration for the focus on royal archives in the present article.Footnote 14 Fortunately, some new clues have been discovered. This article aims to consolidate these clues and attempts to demonstrate how the royal government influenced civic archival activities.

In summary, by examining the case of York, this article intends to address two research questions. The first is when York started the practice of archival preservation. The second is what motivated York to initiate archival preservation. The first section of this article relies on archival analysis to demonstrate that York started keeping records from the late thirteenth century. In building upon the conclusions drawn in the first section, the second section argues that York’s record-keeping was deeply influenced by the royal government. Finally, the conclusion attempts to expound upon the broader geographical implications of this article’s contribution.

New evidence on the origin of record-keeping in York

To examine the beginnings of record-keeping in York, the primary source of importance is the first ‘Freemen’s Register of York’ (henceforth ‘Register’).Footnote 15 The main section of this manuscript comprises lists of individuals who obtained citizenship and those who served as civic officials from 1273 until the seventeenth century.Footnote 16 These lists are organized chronologically, and some individuals’ occupations are mentioned alongside their names.Footnote 17 The significance of the Register in terms of record-keeping lies in the continuity of its contents. Prior to 1370, other civic records lack such continuity. For example, between the late twelfth century and 1370, only 6 of the 11 royal charters granted to the city survive in the civic archives today.Footnote 18 Despite its continuity, the Register presents challenges when it comes to exploring the origins of record-keeping. The scribes did not disclose certain crucial information in the texts, such as their own identities, the reasons behind compiling these lists or the dates of their creation. Moreover, the Register in its current state has undergone multiple edits, making it difficult to reconstruct the original format of the manuscript.Footnote 19

In order to address this issue, historians have primarily relied on palaeographic and textual analysis of the manuscript. Barrie Dobson was the first historian to provide critical commentary on the codicological aspects of the Register. He suggested that the writing of freemen’s lists commenced in around 1310, as it was observed that most of the lists from that period were written ‘in a contemporary or near-contemporary hand’.Footnote 20 According to Dobson’s observations, the lists prior to the 1310s were added to the Register as a whole, whereas lists from the 1310s onwards were added to the manuscript annually. Building upon Dobson’s work, Debbie Cannon investigated the handwriting within the manuscript in search of additional evidence. She discovered that a particular hand found in the freemen’s lists also participated in the writing of mayors’ and bailiffs’ lists. This handwriting was consistently present across three different kinds of lists, dating from 1273 to the 1340s or 1350s. Cannon also observed a distinct pattern in the compilation of mayors’ lists. Between 1273 and 1342, the items were not strictly arranged in annual order: there were instances where consecutive years were combined within a single item. For example, Nicholas le Fleming served as mayor during the fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth and ninth years of Edward II’s reign. Based on this, Cannon argued that the records dating from 1273 to the 1340s or 1350s were likely compiled in one comprehensive effort. Therefore, it was concluded that the lists of citizens, mayors and bailiffs all began to be recorded in the middle of the fourteenth century.Footnote 21

However, it is possible that pre-existing civic records were relied on during the compilation. To test this presumption, it is crucial to conduct thorough investigations of the lists dating from 1273 to the middle of the fourteenth century. If the authenticity of these lists can be established, it would allow for the possibility of tracing the origins of record-keeping in the city even further back. The research conducted for this article focused on three types of lists in the Register: lists of freemen, mayors and bailiffs. These lists represent the earliest sections of the Register, all originating in 1273. Previous studies indicate that the compilation of the Register began in the mid-fourteenth century, making the period of interest for researching the lists from 1273 to 1350. Due to the limited survival of civic records, this study also relied on an exploration of archives beyond the City Archives. The research process consisted of two steps. The first step involved comparing the Register with non-civic records to assess the reliability of the mayors’ and bailiffs’ lists. The aim was to establish the credibility of these lists through systematic comparisons with samples drawn from archives outside of the civic administration. The second step entailed comparing the lists of bailiffs with lists of freemen to further validate the credibility of the latter. This method was chosen for three reasons. Firstly, the names of mayors and bailiffs were frequently recorded in archives beyond the civic administration, providing ample opportunities for systematic comparison and thus increasing the reliability of the findings. Secondly, the names of freemen were not extensively documented in archives outside of the civic administration for an extended period of time. As a result, some comparisons can only be made within civic records. Thirdly, previous research has established that acquiring citizenship was a necessary prerequisite for serving as an urban official.Footnote 22 This insight informed the comparison between the lists of freemen and bailiffs. If confirmed as reliable, the list of bailiffs could serve as a basis for verifying the accuracy of the freemen’s list.

The research on the lists of mayors and bailiffs was based on the examination of title deeds stored in the archives of religious institutions, the Company of the Merchant Adventurers of York and private collectors. Deeds, being legal documents, typically contain a list of witnesses and a time clause. These two pieces of information serve as the foundation for reconstructing independent lists of mayors and bailiffs, separate from the Register. Importantly, these deeds are contemporaneous documents, so reconstructed lists based on information found in the deeds can then be used to verify the accuracy of the Register.

The inclusion of names of mayors and bailiffs in these deeds is due to their involvement in the confirmation of land transactions. Individuals seeking to enhance the visibility and legal validity of their agreements would request the endorsement of someone in a position of public authority. In the case of urban residents, the city court served as the venue for such confirmation.Footnote 23 Aside from relying on written contracts as evidence of legitimacy, the participation of witnesses played a significant role. In York, witnesses in the city court typically consisted of the mayor and three bailiffs. While the number of original contracts still in existence is relatively limited, the transfer of properties, particularly from urban residents to religious institutions, resulted in the transcription of certain deeds by the church. These deeds sometimes survive as separate documents or in other cases were incorporated into cartularies. Additionally, some deeds found their way into the possession of the Company of the Merchant Adventurers of York and of private collectors.

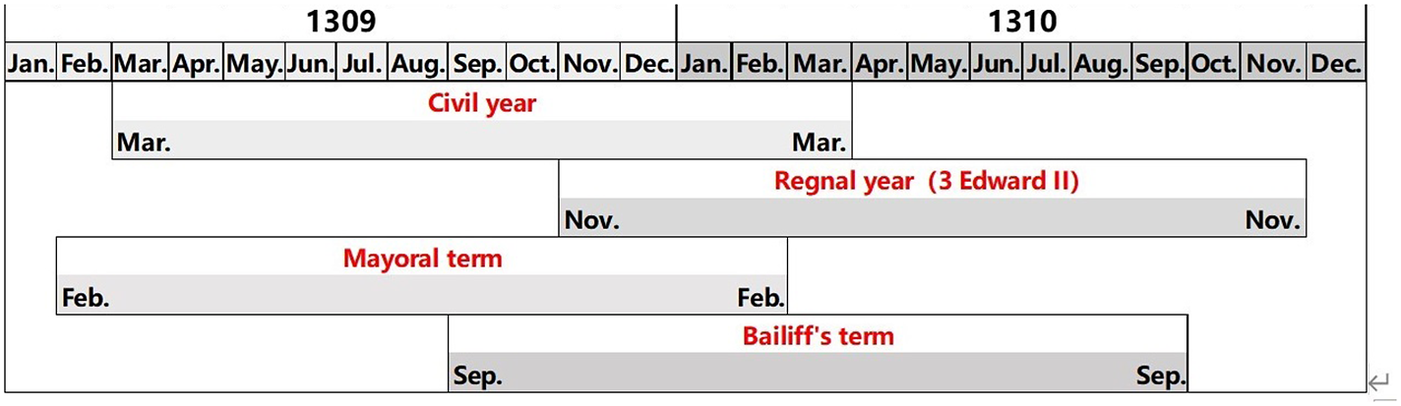

An example can be given to illustrate this rather laborious verification process. A deed dated 17 May 1309 lists the following witnesses: Andrew Bolingbroke, mayor, and Alan de Scoyerschelf, Giles de Brabant and Adam de Pocklington, bailiffs. Based on this information, we can deduce that Bolingbroke served as mayor from February 1309 to February 1310, while Scoyerschelf, Brabant and Pocklington were bailiffs from September 1308 to September 1309.Footnote 24 It will be recalled that the mayoral term in York began in February, whereas the ballival term started in September (see Figure 1). By following this approach, approximately 400 deeds were examined, dated between 1273 and 1350, and the information was used to compile a new list of mayors and bailiffs.Footnote 25 A comparison was then made between this reconstructed list and the lists found in the Register (see Appendices I and II). Although some years had limited information available, the overall findings are clear: the lists of mayors and bailiffs in the Register can be considered reliable and trustworthy.

Figure 1. The co-existence of four dating systems, 1309–10.

Note: In England, from about the late twelfth century until 1751, the civil year began on 25 March. See C.R. Cheney and M. Jones (eds.), A Handbook of Dates for Students of British History (Cambridge, 2000), 12–13.

Once the accuracy of the lists of mayors and bailiffs has been established, attention can be shifted to the lists of freemen. In medieval cities, citizens held a special status, enjoying both economic and political privileges. However, being a citizen also entailed significant financial and personal responsibilities towards the civic administration. Citizenship was a necessary requirement for holding urban office.Footnote 26 Previous research by Dobson indicated that some fourteenth-century mayors and members of parliament in York did not appear in the lists of freemen. This discrepancy might be attributed to the fact that some elite citizens inherited their status.Footnote 27 However, until now there has not been a comprehensive comparison between the lists of freemen and bailiffs to investigate this further. Therefore, the list of bailiffs was chosen as the focus for verifying the accuracy of the list of citizens. By comparing two types of lists, several observations can be made. Firstly, a considerable number of names overlap between the two lists (see Appendix III). Secondly, individuals who served as bailiffs generally obtained their citizenship 10 to 20 years beforehand. This pattern can explain why those who began their roles as bailiffs from 1297 appear more frequently in the list of freemen, as individuals serving between 1273 and 1297 might have gained their citizenship before 1273. Given that this study focuses on the list of freemen between 1273 and 1350, the examination of bailiffs is confined to the period from 1297 to 1370. The research findings reveal that almost 50 per cent of the bailiffs appeared in the freemen’s list. Clearly, this does not suggest that all bailiffs came from the citizenry. However, considering that the list of freemen probably excludes citizens who acquired their status through inheritance, it is still plausible to conclude that the list of freemen between 1273 and 1350 is highly dependable.

In conclusion, the research conducted on the lists of mayors, bailiffs and freemen from 1273 to 1350 supports their reliability. Although the compilation of the extant Register occurred later than the dates mentioned within its text, it is likely that the compilation was based on pre-existing civic records. The high level of accuracy achieved in the Register suggests that it was built upon reliable sources. However, the specific sources cannot be definitively determined. Based on the findings, one of two inferences may be drawn. The first is that certain official documents may have been preserved in York from 1273 onwards, which served as the basis for compiling the lists in the mid-fourteenth century. Alternatively, actual lists of freemen and urban officials may have been kept in York from 1273. These lists were possibly maintained and later transcribed into the extant Register, which represents a continuation of this record-keeping tradition. The evidence indicates that the city administration of York began valuing the preservation of records by the late thirteenth century.

An age of transition: the reign of Edward I

The transition from the creation to the preservation of records occurred during the reign of Edward I. In this period, the royal government actively engaged with local society through various policies. Edward introduced comprehensive legislation and initiated inquiries to regulate and govern the realm.Footnote 28 He also aimed to strengthen feudal income collection and establish a system of national taxation.Footnote 29 These developments led to new requirements for local administration. One notable event during Edward’s reign was the Quo Warranto campaign, which aimed to investigate the origin and exercise of franchises.Footnote 30 This campaign encouraged towns to document the customs and practices they had previously relied upon but had never formally recorded.Footnote 31 While it may initially appear that York differed from other towns in this regard, since its compilation of custumals did not start until the 1370s, there is evidence to suggest that York’s civic administrative literacy was influenced by the royal government in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. This influence likely played a role in shaping the record-keeping practices of the city.

In 1280, York faced a loss of its liberties due to the mayor’s mishandling of a royal charter. This incident occurred in the context of the Quo Warranto proceedings, which involved an inquiry into the jurisdiction of the citizens of York over the Ainsty, a neighbouring rural wapentake to the west of York.Footnote 32 It is likely that the city had sought to extend its authority over this area after gaining civic autonomy in the early thirteenth century.Footnote 33 During the proceedings, the mayor of York presented a charter granted by King John as evidence of the city’s jurisdiction. However, doubts arose regarding the authenticity of this charter. An erasure was discovered in the regnal year, specifically the word ‘fourth’. A comparison with a copy preserved at the royal Exchequer led to the conclusion that the charter was actually made in the fifteenth year of King John’s reign (1213–14).Footnote 34 This event highlights the importance of document integrity, as any alterations or discrepancies could be detected through consultation of original copies in the royal archives. The use of a potentially falsified charter resulted in the suspension of York’s civic liberties for three years.Footnote 35

The loss of autonomy experienced by York had a profound impact on the civic community and influenced its subsequent approach to the preservation and use of records. This is evidenced by events between 1300 and 1315, during which time York’s urban officials presented royal charters on three separate occasions. In 1300, a jurisdictional dispute arose between the city and St Leonard’s Hospital. The mayor and bailiffs of York defended their position by presenting a charter granted by King Henry III in 1256, which served as evidence of the city’s rights and privileges.Footnote 36 In 1306, another challenge emerged for York’s civic administration when it was revealed to royal justices that a secret association called the ‘gildebrethere’ had been established within the city. This guild included prominent citizens such as Andrew de Bolingbroke, the current mayor, as well as other future or former civic officials. In their defence, the guild members presented the same charter that had been used in 1300 as proof of civic liberties.Footnote 37 In 1315, a dispute arose between the chapter and the city regarding the ownership of a property situated at the corner of Petergate and Stonegate, near the Minster Close. On this occasion, civic officials presented a charter granted by King Edward II in 1312 to support their claim.Footnote 38 These examples demonstrate that York’s urban officials used charters competently and honestly from the 1300s. The repercussions of the royal punishment in 1280 had instilled in the city a heightened concern for the preservation and utilization of records. The civic community recognized the importance of having valid charters to assert their rights and privileges, and they made deliberate efforts to ensure the careful preservation and presentation of these documents when necessary.

The restoration of civic liberties to York in 1283 coincided with the issuance of the Statute of Acton Burnell (1283) by the royal government, which was followed by the Statute of Merchants in 1285. These statutes allocated the responsibility of registering debts to several major towns in England, including York.Footnote 39 Under this system, debtors and creditors could appear before the mayor and a clerk appointed by the king to have their debts officially recognized. If a debt remained unpaid beyond the agreed-upon time, the creditor had the option to present the bond at the registry to seek assistance. In cases where a debtor was a citizen of York, civic officials held the authority to seize and sell his movables and burgages to recover the debt. However, if the debtor’s wealth extended beyond the jurisdiction of the city, the mayor had to certify the bond and submit it to the royal chancery. The chancery would issue a writ to the sheriff of the county where the debtor had acquired wealth, enabling the execution of the debt recovery process.Footnote 40 The execution of the Statute of Acton Burnell and the Statute of Merchants in York can be evidenced by the certificates sent from York’s civic officials to the royal chancery.Footnote 41 These certificates would have served as documentation of the actions taken by the city to enforce debt repayments and engage in the legal processes outlined in the statutes.

The implementation of these statutes had a significant impact on the preservation of records in York. The Ordinance of Jewry in 1194 can be seen as a potential predecessor to the Statute of Acton Burnell. This ordinance established a chest, known as the arche, in York, which was used to store records of debts owed by Christians to Jews.Footnote 42 However, it did not lead to the successful development of a local archive, possibly due to the negative associations with Jewish moneylending and usury at that time, as noted by Clanchy.Footnote 43 In contrast, the Statute of Acton Burnell and the Statute of Merchants focused on the registration of debts between Christians, which likely helped avoid the previous enmity towards an archive. The functioning of these statutes relied on the involvement of prominent burgesses, including the mayor and the statute clerk or deputy clerk, who were often individuals from York.Footnote 44 These clerks were responsible for maintaining registers for the enrolment of debts, indicating the establishment of an office dedicated to this task. This development may have played a role in the subsequent appearance of the town clerk, whose responsibility was to preserve civic records. For example, Nicholas de Sezevaux, noted as ‘clerk of the city’ in 1317 and 1327, also served as a deputy statute clerk between 1308 and 1317.Footnote 45 This suggests a connection between these two roles before the establishment of the common clerk as an official civic position in the 1370s.Footnote 46 The close relationship between the enforcement of the statutes and the appointment of clerks for record-keeping likely contributed to the development of a more formalized system for preserving civic records in York.

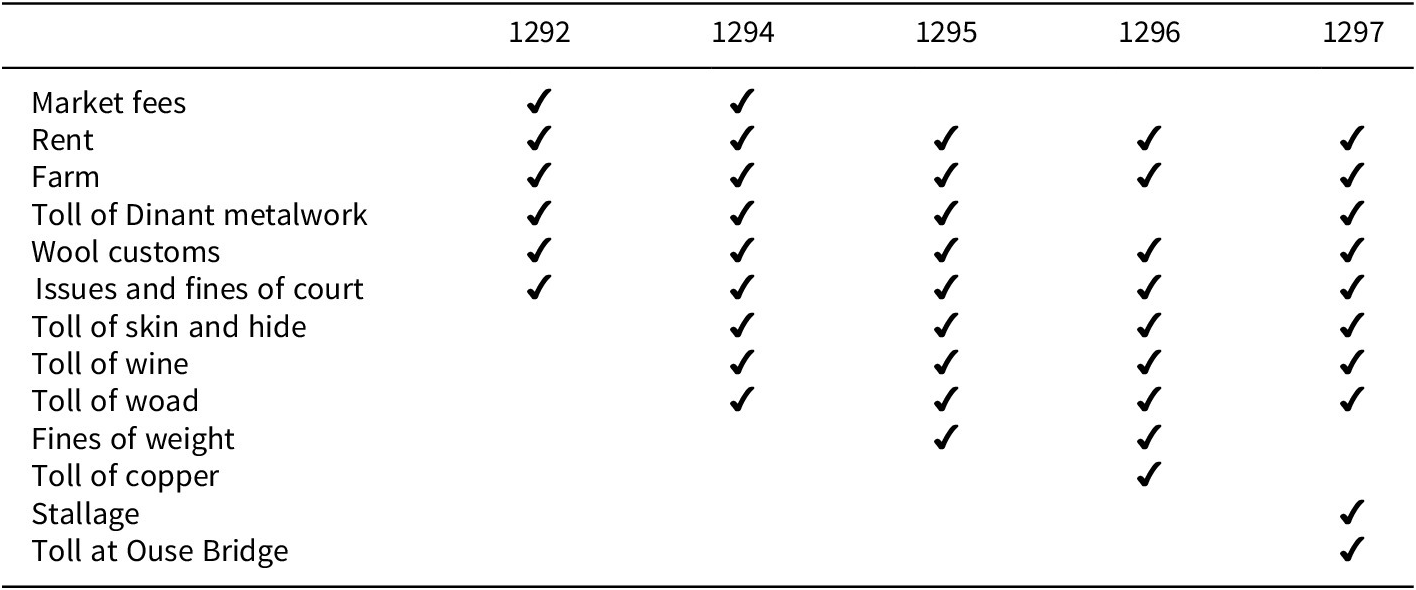

In 1292, York experienced another loss of liberties due to outstanding debts owed to the crown, which were a result of the financial strain caused by Edward I’s Welsh wars. The second Welsh war concluded in 1283, and the royal Exchequer began efforts to recover old crown debts.Footnote 47 In the 1290s, several towns, including York, had their liberties revoked due to their outstanding debts.Footnote 48 From 1292 to 1297, the sheriff of Yorkshire served as the keeper of York while the town was in the king’s hands. During this period, financial accounts were recorded (see Table 1). Initially, the sources of the fee farm were not yet well regulated. There was no established rule regarding the contributions to the farm, although certain items, such as wool customs and court revenues, were commonly included in the accounts. The accounts also reveal inconsistencies in the categorization of income sources. For instance, the pasture of ditches (herbagio fossatorum civitatis Eboraci) was categorized as part of the ‘Farm’ item in the accounts of 1295 and 1296, but it belonged to the ‘Rent’ item in the accounts of 1293 to 1295.Footnote 49 The ambiguity suggests that detailed accounts may not have been preserved by the city during this period. The collection of the farm was likely based on customary practices rather than comprehensive written records. The non-preservation of records may be attributed to the fact that the royal Exchequer was primarily concerned with the final payment, so the bailiffs of York might not have felt compelled to keep detailed accounts. However, the keepers’ accounts indicate that the sources of the farm were gradually being regulated and expanded. Because accounts were regularly written and preserved, officials had the opportunity to revise them and add new items. A comparison between the 1292 and 1294 accounts shows the addition of three new particulars. For instance, tolls of wine and woad were included in the account of 1294 before they were actually collected.Footnote 50 In 1297, stallage and toll at Ouse Bridge, previously part of the ‘Farm’ item, became separate items, with detailed records of their particulars.Footnote 51

Table 1. Financial accounts of York’s keepers, 1292–97

Source: TNA, SC 6/1088/13.

Upon the restoration of civic liberties in York, it is likely that the accounts of the farm started to be preserved by the city. A notable incident sheds light on this preservation. On 22 May 1380, a butcher from York lodged a complaint with the royal Exchequer. He claimed that the bailiffs of York had visited his house and extorted one penny from him every Sunday since 2 October 1379. The bailiffs justified this levy as stallage, which was considered part of the farm. They further asserted that the fixed amount for this levy had been recorded in royal rolls during the period when Edward I took control of the city.Footnote 52 While the bailiffs of York did not refer specifically to civic accounts in their explanation, the fact that they made reference to royal records implies that some civic financial accounts existed, enabling urban officials to recall events that had taken place a century prior. Therefore, the management of civic finance by royal officials facilitated the preservation of civic financial accounts.

From 1298 to 1338, York served as a ‘second home for English royal government’.Footnote 53 The royal household and various departments of the government, including the Exchequer, Common Pleas and King’s Bench, frequently relocated to York. Additionally, 13 parliamentary sessions were held in the city during this period.Footnote 54 The government departments established their headquarters in the royal castle, St Mary’s, Castlegate, St Mary’s Abbey and the minster chapter house.Footnote 55 Historians such as Michael Prestwich and Mark Ormrod have discussed the implications of this relocation on York’s economy, politics and culture.Footnote 56 However, they did not fully consider the influence on civic governance when the royal government was present in the city. Given that the royal government had already established a system of writing and preserving records in the early thirteenth century, it is reasonable to assume that royal records would have been transferred to York along with the government officials. An example of this can be seen in 1300, when certain books and wardrobe rolls were stored at St Leonard’s Hospital of York.Footnote 57 When the government worked at York, the writing, preservation and use of records continued. As a result, the civic administration of York would have had the opportunity to observe and learn from the practices of the royal government. The interest in royal archives can be demonstrated by the survival of two folios in the first ‘Freemen’s Register of York’. Despite the misleading title, the contents of this manuscript were actually miscellaneous and included accounts and royal writs related to national taxation levied in the 1330s and the 1340s.Footnote 58 Marginal notes indicate that these records were copied from Exchequer rolls.Footnote 59 This suggests that civic officials in York consulted royal archives while the government was located in the city. Such exchange of knowledge and practices between the royal government and the civic administration had a notable impact on record-keeping and governance in the city.

During the period when the royal government stayed in York, it took actions to intervene in the governance of the city. This intervention prompted York’s officials to enhance their management of commerce by the use of records. The presence of the royal government in York attracted officials, lawyers and others to migrate to the city. In 1301, complaints arose that an influx of immigrants had caused a shortage of food, leading to price increases. In response to these concerns, the royal council issued a series of ordinances to regulate high prices and address commercial malpractice in the city. These ordinances were based on national decrees or regulations that were established when London was in the king’s hands (1285–98). However, the York ordinances were ‘remarkably full and comprehensive’, and exhibited greater strictness compared to parallel ones in London and Bristol.Footnote 60 This suggests that the royal government was more ambitious in its governance of York than of London. Ormrod argued that the removal of the royal government from Westminster to York was a means of punishing the citizens of London and avoiding the complexities of political activities in the south.Footnote 61 The different circumstances in the north may explain why the royal government took a more stringent approach to governing York.

The execution of the 1301 ordinances issued by the royal government required the active use of records, as shown in the following ordinance:

For the maintenance and observance of these ordinances, the mayor, bailiffs and other worthy men sworn for the purpose are to summon all those of the trades mentioned above before them, and have their names enrolled, so that each shall swear to exercise his calling in the manner set out above.Footnote 62

This new requirement placed a clear emphasis on the need for civic officials to write and preserve records. The registration of practitioners’ names, which had likely never been recorded before, can be seen as a form of inquiry conducted within the city. However, this new policy might have caused disturbance or resistance among the residents of York. In 1304, the royal council received complaints and initiated an inquiry into the enforcement of these ordinances. The jurors summoned for the inquiry reported that most of ordinances were not observed by the urban officials.Footnote 63 Nevertheless, the registration of names was carried out with the assistance of royal authority. The jurors compiled a list of practitioners who disobeyed the ordinances, amounting to 384 individuals across 10 trades.Footnote 64 While the lists of transgressors may not be identical to the lists of freemen, it is undeniable that such a large-scale registration process had implications for the writing and preservation of civic records.

In sum, during the reign of Edward I, the royal government exerted increased control over local society, including the civic administration of York. The city experienced interventions, the loss of autonomy and even served as a temporary capital. The royal government played a significant role in introducing record-keeping practices to York in this period. The Quo Warranto proceedings required franchise-holders to produce documentary evidence to prove the legitimacy of their rights. The consequences of misusing a royal charter led York’s officials to pay more attention to the preservation of such charters, which became crucial in establishing the legitimacy of civic privileges. The establishment of York as a registry for debts encouraged the preservation of records within the city. The Statute of Acton Burnell and the Statute of Merchants further refined the registration process for debts among Christians, making local archives more widely accepted by society. The creation of the statute clerk’s office, a precursor to the office of town clerk, emphasized the importance of record-keeping, specifically in relation to recognizances. With expanding financial needs, the royal government facilitated the writing and preservation of financial records in York. Sheriffs of Yorkshire who managed York’s finances produced a large number of financial records from 1292 to 1297, providing a model for civic officials to regulate and expand revenue sources. References to royal archives in the late 1370s suggest that this type of record-keeping continued over time. Beginning in 1297, the migration of the royal government to York provided the city with convenient access to the bureaucratic and archival mechanisms of the royal government. In 1301, the direct intervention of the royal government in York’s commercial activities further emphasized the importance of internal management through record-keeping. Overall, the intervention of royal authority in the autonomy of York led to the spread of record-keeping practices from the central to the local level. This shift played a crucial role in shaping the preservation and use of records within the civic administration of York.

Conclusion

This article has addressed the development of York’s civic administrative literacy before the third quarter of the fourteenth century, a subject which has not been adequately explained by previous historians. The focus was on the transition from record-writing to record-keeping. The article has provided evidence that York began to exhibit signs of archival preservation at the end of the thirteenth century. The lists of freemen, mayors and bailiffs from the 1270s were among the earliest records preserved by the city. Additionally, through an examination of the relationship between York and the royal government, this article has demonstrated that York was deeply influenced by the policies and interventions of the royal government during the reign of Edward I. The royal government employed various methods to strengthen its control over local society, some of which were specific to York. Importantly, there is evidence to suggest that royal intervention strongly facilitated the preservation of records in York. Therefore, the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries were a critical period for York’s transition from record-writing to record-keeping. This period marked the development of York’s civic administrative literacy.

The eleventh and twelfth centuries witnessed a revival of archives in various regions across Europe, as new political and religious organizations started preserving records.Footnote 65 Studies referenced in the introduction indicate that both English and continental towns underwent the development of civic administrative literacy. Researchers desiring to study the early stages of civic administrative literacy often face the problem that there is limited information preserved in civic records. An approach that compares a range of historical sources can overcome this problem because it can explain whether existing records derive from earlier sources, thereby facilitating the reconstruction of the contextual landscape of early civic administrative literacy. In addition, the case-study of York has provided valuable insights into the influence of the royal government on the initiation of record-keeping by the city administration. This perspective is probably not unique to York, as royal governments across Europe often established chanceries prior to the flourishing of civic administration, and these chanceries served as models for cities to learn from in terms of record-keeping practices. While historians have often noted this possibility, it has not previously been explained in detail, no doubt due to the limited sources available. It is unlikely that civic records would explicitly refer to the source of influence. This article has provided an example of how to demonstrate royal influence by relying on evidence collected from royal records. This case-study may perhaps serve as a model for future research on the beginnings of urban record-keeping in other regions.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0963926823000767.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Dr Tom Johnson, Prof. Sarah Rees Jones, Prof. Rong Xiang and the audience at seminars of Fudan for their advice on this piece. I also wish to thank the anonymous peer reviewers and the editors at Urban History for their helpful feedback.

Funding statement

This study is funded by the National Social Science Fund of China (grant number: 23CSS008) and Shanghai Post-doctoral Excellence Program (certificate number: 2023215).