Palmer amaranth is a summer annual broadleaf weed belonging to the family Amaranthaceae (Sauer Reference Sauer1957; Steckel Reference Steckel2007). Though it is native to the southwestern United States, human activities in the 20th century—including seed and equipment transportation and agriculture expansion—have led Palmer amaranth to spread to the northern United States (Culpepper et al. Reference Culpepper, Webster, Sosnoskie and York2010). Palmer amaranth is a dioecious species, with pollination occurring by wind (Franssen et al. Reference Franssen, Skinner, Al-Khatib, Horak and Kulakow2001). It is a prolific seed producer even under competition with agronomic crops (Burke et al. Reference Burke, Schroeder, Thomas and Wilcut2007; Massinga et al. Reference Massinga, Currie, Horak and Boyer2001). A single female plant, if not controlled, can produce as many as 600,000 seeds (Keeley et al. Reference Keeley, Carter and Thullen1987). Palmer amaranth has the greatest plant dry weight, leaf area, height, growth rate (0.10 to 0.21 cm per growing degree day), and water-use efficiency of all the pigweeds, including Amaranthus rudis Sauer, Amaranthus retroflexus L., and Amaranthus albus L. (Horak and Longhin Reference Horak and Loughin2000). Palmer amaranth’s aggressive growth habit and prolific seed production make it a pervasive weed in agronomic crop production fields (Bensch et al. Reference Bensch, Horak and Peterson2003; Liphadzi and Dille Reference Liphadzi and Dille2006; Massinga et al. Reference Massinga, Currie, Horak and Boyer2001; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Baker and Steele2000). A recent survey conducted by the Weed Science Society of America found that Palmer amaranth was the most problematic agricultural weed in the United States (WSSA 2016).

The continuous and sole reliance on single mode-of-action herbicide programs has resulted in the evolution of herbicide-resistant weeds (Beckie Reference Beckie2011; VanGessel Reference VanGessel2001). Palmer amaranth biotypes resistant to microtubule-inhibiting herbicides were reported first, followed by biotypes resistant to acetolactate synthase (ALS)-, photosystem II (PSII)-, 5-enol-pyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS)-, hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (HPPD)-, and protoporphyrinogen oxidase (PPO)-inhibiting herbicides (Heap Reference Heap2016a). In addition, Palmer amaranth resistant to multiple herbicides (e.g., ALS-, EPSPS-, HPPD-, and PSII-inhibitors) has been reported in a few states (Heap Reference Heap2016a). In Nebraska, a Palmer amaranth biotype resistant to HPPD- and PSII-inhibitors has been reported (Jhala et al. Reference Jhala, Sandell, Rana, Kruger and Knezevic2014).

Glyphosate, a systemic and broad-spectrum herbicide, is the most widely used agricultural pesticide globally due to the widespread adoption of glyphosate-resistant (GR) crops and minimum or no-tillage practices that rely primarily on herbicides for weed control (Woodburn Reference Woodburn2000). Since the commercialization of GR crops, glyphosate has been extensively used for POST weed control in GR corn and soybean fields in the Midwest. The estimated total glyphosate use in the United States was 18 million kg active ingredient per year in 1996, but rose to 125 million kg in 2013, a 594% increase (USGS 2016). Glyphosate inhibits the EPSPS enzyme, a component of the shikimate pathway. Glyphosate thus prevents the biosynthesis of the aromatic amino acids phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan, resulting in the death of glyphosate-sensitive plants due to the accumulation of shikimate (Herrmann and Weaver Reference Herrmann and Weaver1999; Steinrücken and Amrhein Reference Steinrücken and Amrhein1980). Rigid ryegrass (Lolium rigidum Gaudin) in Australia in 1996 was the first confirmed GR weed (Powles et al. Reference Powles, Lorraine-Colwill, Dellow and Preston1998), and GR Palmer amaranth was first documented in Georgia in 2004 (Culpepper et al. Reference Culpepper, Grey, Vencill, Kichler, Webster, Brown, York, Davis and Hanna2006). Since then, Palmer amaranth populations resistant to glyphosate have been documented in 25 other states in the United States (Heap Reference Heap2016a).

Mechanisms of glyphosate resistance have been studied in several weed species (Dinelli et al. Reference Dinelli, Marotti, Bonetti, Catizone, Urbano and Barnes2008; Perez-Jones et al. Reference Perez-Jones, Park, Polge, Colquhoun and Mallory-Smith2007; Simarmata and Penner Reference Simarmata and Penner2008; Wiersma et al. Reference Wiersma, Gaines, Preston, Hamilton, Giacomini, Robin Buell, Leach and Westra2015). Glyphosate resistance has been conferred by a) target site mutation in the EPSPS gene, making it insensitive to the target protein (Kaundun et al. Reference Kaundun, Dale, Zelaya, Dinelli, Marotti, McIndoe and Cairns2011; Perez-Jones et al. Reference Perez-Jones, Park, Polge, Colquhoun and Mallory-Smith2007; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Cairns and Powles2007), b) reduced absorption and translocation of glyphosate (Dinelli et al. Reference Dinelli, Marotti, Bonetti, Catizone, Urbano and Barnes2008; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Cairns and Powles2007; Wakelin et al. Reference Wakelin, Lorraine-Colwill and Preston2004), c) increased glyphosate sequestration (Ge et al. Reference Ge, d’Avignon, Ackerman and Sammons2010), and d) EPSPS gene amplification (Chandi et al. Reference Chandi, Milla-Lewis, Giacomini, Westra, Preston, Jordan, York, Burton and Whitaker2012; Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Zhang, Wang, Bukun, Chisholm, Shaner, Nissen, Patzoldt, Tranel, Culpepper, Grey, Webster, Vencill, Sammons, Jiang, Preston, Leach and Westra2010; Jugulam et al. Reference Jugulam, Niehues, Godar, Koo, Danilova, Friebe, Sehgal, Varanasi, Wiersma, Westra, Stahlman and Gill2014; Whitaker et al. Reference Whitaker, Burton, York, Jordan and Chandi2013). The presence of EPSPS gene copies (>100 copies) distributed throughout the genome has been confirmed in a GR Palmer amaranth biotype from Georgia (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Zhang, Wang, Bukun, Chisholm, Shaner, Nissen, Patzoldt, Tranel, Culpepper, Grey, Webster, Vencill, Sammons, Jiang, Preston, Leach and Westra2010). Additionally, EPSPS gene amplification has been reported in Palmer amaranth populations from North Carolina (Chandi et al. Reference Chandi, Milla-Lewis, Giacomini, Westra, Preston, Jordan, York, Burton and Whitaker2012; Whitaker et al. Reference Whitaker, Burton, York, Jordan and Chandi2013), Mississippi (Ribeiro et al. Reference Ribeiro, Pan, Duke, Nandula, Baldwin, Shaw and Dayan2014), and New Mexico (Mohseni-Moghadam et al. Reference Mohseni-Moghadam, Schroeder and Ashigh2013a). Low levels of resistance to glyphosate due to reduced uptake and translocation have also reported in Palmer amaranth biotypes from Tennessee (Steckel et al. Reference Steckel, Main, Ellis and Mueller2008) and Mississippi (Nandula et al. Reference Nandula, Reddy, Kroger, Poston, Rimando, Duke, Bond and Ribeiro2012).

In numerous instances, persistent reliance on glyphosate for broad-spectrum and economical weed control has resulted in the evolution of GR weeds. Failure to control Palmer amaranth following sequential glyphosate applications was observed in a grower’s field in Thayer County in south-central Nebraska. The field was under GR corn–soybean rotation with reliance on glyphosate for weed control in a no-till production system, justifying the need to evaluate the level of resistance and the mechanism involved to confer resistance. It was also deemed important to determine whether the Palmer amaranth biotype had reduced sensitivity to herbicides with other modes of action that can be used in corn and soybean. This information can be used to develop herbicide programs for the management of resistant Palmer amaranth. The objectives of this study were 1) to confirm the presence of GR Palmer amaranth in south-central Nebraska by quantifying the level of resistance in a whole-plant dose-response bioassay, 2) to compare the EPSPS gene copy number of GR Palmer amaranth with that of the susceptible biotype, and 3) to evaluate the response of GR Palmer amaranth to POST herbicides that can be used in corn and soybean.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials

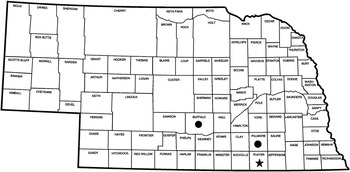

In October 2015, Palmer amaranth plants that survived sequential glyphosate applications were collected from a grower’s field in Thayer County, Nebraska (40.30°N, 97.67°E) (Figure 1) to serve as the putative GR biotype in this study. Palmer amaranth seed heads were collected from fields in Buffalo and Fillmore Counties in Nebraska (Figure 1); both fields have a known history of effective control with the recommended rate of glyphosate. These were considered the glyphosate-susceptible (GS) biotypes in this study, and named susceptible 1 (S1) and susceptible 2 (S2). The seeds were cleaned thoroughly using a seed cleaner and stored separately in airtight polyethylene bags at 5 C until used in this study. Seeds were planted in square plastic pots (10×10×12 cm) containing a 2:2:2:4 (by vol) soil:sand:vermiculite:peat moss mixture. Palmer amaranth plants were thinned to one plant per pot at 10 d after emergence. The plants were supplied with water and nutrients and kept in a greenhouse maintained at a 30/27 C day/night temperature regime with a 16-h photoperiod supplemented by overhead sodium halide lamps.

Figure 1 South-central Nebraska counties from which suspected glyphosate-resistant (★) and glyphosate-susceptible (●) Palmer amaranth seeds were collected.

Whole-Plant Dose-Response Bioassay

Greenhouse whole-plant dose-response bioassays were conducted in 2016 at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln to determine the level of resistance in the putative GR Palmer amaranth biotype. The two GS biotypes were included for comparison. The study was laid out in a 10 by 3 factorial experiment in a randomized complete block design with four replications. Ten glyphosate rates were used: 0, 0.25×, 0.5×, 1×, 2×, 4×, 8×, 16×, 32×, and 64×, where 1× indicates the recommended field rate of glyphosate (870 g ae ha─1). The three Palmer amaranth biotypes used were R, S1, and S2. The experiment was repeated twice under similar growing conditions mentioned above. A single Palmer amaranth plant per pot was considered an experimental unit. Seedlings were treated with glyphosate (Roundup PowerMax®, Monsanto Company, 800 North Lindberg Ave., St. Louis, MO) at the six- to seven-leaf stage (8 to 10 cm tall). Each glyphosate treatment was prepared in distilled water and mixed with 0.25% v/v nonionic surfactant (Induce®, Helena Chemical Co., Collierville, TN) and 2.5% wt/v ammonium sulfate (DSM Chemicals North America Inc., Augusta, GA).

Herbicide treatments were applied using a single-tip chamber sprayer (DeVries Manufacturing Corp, Hollandale, MN 56045) fitted with a 8001E nozzle (TeeJet®, Spraying Systems Co., Wheaton, IL 60187) calibrated to deliver 190 L ha─1 carrier volume at 207 kPa. Palmer amaranth control was assessed visually at 7, 14, and 21 d after treatment (DAT) using a scale ranging from 0% (no control) to 100% (complete control or death of plants). These control scores were based on symptoms such as chlorosis, necrosis, stand loss, and stunting of plants compared with non-treated control plants. Aboveground biomass of each Palmer amaranth plant was harvested at 21 DAT and oven-dried for 4 d at 65 C, and dry weights (biomass) were determined. The biomass data were converted into percent biomass reduction compared with the non-treated control plants (Wortman Reference Wortman2014, using the following formula:

where

![]() $\bar{C}$

is the mean biomass of the four non-treated control replicates and B is the biomass of an individual treated experimental unit. Using the drc 2.3 package c in R statistical software version 3.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), a three-parameter log-logistic function was used to determine the effective dose of glyphosate needed to control each Palmer amaranth biotype by 50% (ED50) and 90% (ED90) (Knezevic et al. Reference Knezevic, Streibig and Ritz2007):

$\bar{C}$

is the mean biomass of the four non-treated control replicates and B is the biomass of an individual treated experimental unit. Using the drc 2.3 package c in R statistical software version 3.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), a three-parameter log-logistic function was used to determine the effective dose of glyphosate needed to control each Palmer amaranth biotype by 50% (ED50) and 90% (ED90) (Knezevic et al. Reference Knezevic, Streibig and Ritz2007):

where Y is the percent control score or percent aboveground biomass reduction, x is the herbicide rate, d is the upper limit, e represents the ED50 or ED90 value, and b represents the relative slope around the parameter e. The level of resistance was calculated by dividing the ED90 value of the resistant biotype by that of the susceptible biotypes, S1 and S2. Where the ED90 values for S1 and S2 were dissimilar, a range of resistance levels is provided.

Genomic DNA Isolation

The putative GR and GS Palmer amaranth plants were grown under greenhouse conditions at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln using the same procedures reported for the whole-plant dose-response study. GR Palmer amaranth plants were sprayed with 0, 1×, 2×, and 4× rates of glyphosate using a single-tip chamber sprayer as described in the whole-plant dose-response study. Fresh leaf tissue was collected from untreated GS and GR as well as from treated GR Palmer amaranth plants that survived the 1×, 2×, and 4× rates of glyphosate at 21 DAT. The harvested leaf tissue was immediately flash frozen in liquid nitrogen (−195.79 C) and stored at −80 C for genomic DNA (gDNA) isolation and extracted from frozen leaf tissue (100 mg) using an EZNA® Plant DNA kit (Omega bio-tek, Norcross, GA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The isolated gDNA was then quantified on a NanoDrop® spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

EPSPS Gene Amplification

A quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed using a StepOnePlusTM real-time detection system (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA) to determine the EPSPS gene copy number in plants that survived glyphosate application. The qPCR reaction mix (14 µL) consisted of 8 µL of PowerUpTM SYBRTM Green master mix (Applied Biosystems), 2 µL each of forward and reverse primers (5 µM), and 2 µL of gDNA (20 ng/µL). The qPCR reaction plate (96-well) was set up with three technical and three biological replicates. The qPCR conditions were 95 C for 15 min, 40 cycles of 95 C for 30 s, and an annealing at 60 C for 1 min. The forward and reverse primers used for amplifying the EPSPS gene were: 5′-ATGTTGGACGCTCTCAGAACTCTTGGT-3′ and 5′-TGAATTTCCTCCAGCAACGGCAA-3′ with an amplicon size of 195 bp (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Zhang, Wang, Bukun, Chisholm, Shaner, Nissen, Patzoldt, Tranel, Culpepper, Grey, Webster, Vencill, Sammons, Jiang, Preston, Leach and Westra2010). β-Tubulin was used as a reference gene for normalizing the qPCR data. The forward and reverse primers used for amplifying the β-tubulin gene were: 5′-ATGTGGGATGCCAAGAACATGATGTG-3′ and 5′-TCCACTCCACAAAGTAGGAAGAGTTCT-3′ with an amplicon size of 157 bp (Godar et al. Reference Godar, Varanasi, Nakka, Prasad, Thompson and Mithila2015). A melt curve profile was included following the thermal cycling protocol to determine the specificity of the qPCR products. Relative EPSPS copy number was assessed using the formula for fold induction (2−ΔΔCt) (Pfaffl Reference Pfaffl2001). The EPSPS copies were measured relative to the calibrator sample SNT1 (a known glyphosate-susceptible sample).

Response to POST Corn and Soybean Herbicides

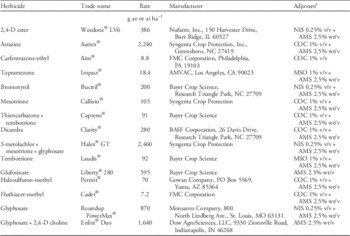

The response of GR Palmer amaranth to POST corn and soybean herbicides was evaluated. Treatments included registered POST corn (Table 1) and soybean (Table 2) herbicides applied at the rates recommended on the labels. Plants were grown under greenhouse conditions at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln using the same procedures reported for the whole-plant dose-response study. Separate experiments were conducted for POST corn and soybean herbicides in randomized complete block designs with four replications. Herbicides were applied when GR Palmer amaranth plants were 8 to 10 cm tall, using the same chamber-track sprayer used in the whole-plant dose-response study. Palmer amaranth control scores were recorded at 7, 14, and 21 DAT on a scale of 0% to 100% as described in the dose-response study. At 21 DAT, plants were cut at the soil surface and oven-dried for 4 d at 65 C, after which dry biomass weights were recorded. Percent biomass reduction of treated plants was calculated using Equation 1. Experiments were repeated twice.

Table 1 Details of POST corn herbicides used in a greenhouse study at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln to determine response of glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth.

a Abbreviations: AMS, ammonium sulfate (DSM Chemicals North America Inc., Augusta, GA); COC, crop oil concentrate (Agridex®, Helena Chemical Co., Collierville, TN); MSO, methylated seed oil (Southern Ag Inc., Suwanee, GA); NIS, nonionic surfactant (Induce®, Helena Chemical Co., Collierville, TN).

Table 2 Details of POST soybean herbicides used in a greenhouse study at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln to determine response of glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth.

a Abbreviations: AMS, ammonium sulfate (DSM Chemicals North America Inc., Augusta, GA); NIS, nonionic surfactant (Induce®, Helena Chemical Co., Collierville, TN). MON 10 (Monsanto Company, 800 North Lindberg Ave., St. Louis, MO) is an adjuvant to be used at 2% v/v with Roundup Xtend®.

Data were subjected to ANOVA using the PROC GLIMMIX procedure in SAS® version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Data for corn and soybean herbicides were analyzed separately to determine the difference in Palmer amaranth response to different herbicide treatments. Control score and biomass reduction data were analyzed without values from the non-treated control plants. Herbicide treatment, DAT, experimental run, and their interactions were considered fixed effects, whereas replication was considered a random effect in the model. Before analysis, data were tested for normality and homogeneity of variance using PROC UNIVARIATE. Normality and homogeneity of variance assumptions were met; therefore, no data transformation was needed. Control score and percent biomass reduction means were separated using Fisher’s LSD test at P≤0.05.

Results and Discussion

Whole-Plant Dose-Response Bioassay

Experiment by treatment interactions for Palmer amaranth control (P=0.061) and biomass reduction (P=0.083) were not significant; therefore, data from both experiments were combined. Glyphosate applied at the label-recommended rate (870 g ae ha−1) controlled both GS Palmer amaranth biotypes 96%, whereas the GR biotype was only 19% controlled (Figure 2). To achieve 50% and 90% control of the GR Palmer amaranth biotype required glyphosate rates of 1,787 and 14,420 g ae ha–1, 2- and 17-fold the labeled rate, respectively . The GR Palmer amaranth biotype was controlled only 90% by the highest glyphosate rate (55,040 g ha–1) tested in this study. The ED50 and ED90 values of the two susceptible biotypes were similar, ranging from 73 to 94 g ha–1 and 360 to 393 g ha–1, respectively. On the basis of ED90 values, the GR biotype had a 37- to 40-fold level of resistance depending on the susceptible biotype being used for comparison (Table 3). Culpepper et al. (Reference Culpepper, Grey, Vencill, Kichler, Webster, Brown, York, Davis and Hanna2006) reported 50% control of a GR Palmer amaranth biotype from Georgia with glyphosate applied at 1,200 g ha–1, and Norsworthy et al. (Reference Norsworthy, Griffith, Scott, Smith and Oliver2008) reported 50% control of a GR Palmer amaranth biotype from Arkansas with glyphosate applied at 2,820 g ha−1, 1.57-fold higher application rate than that observed in this study (1,787 g ha−1).

Figure 2 Dose-response curves of glyphosate-resistant (R) and -susceptible (S1 and S2) biotypes from Nebraska. (A) Control at 21 days after treatment, and (B) percent biomass reduction at 21 days after treatment, in a greenhouse whole-plant glyphosate dose-response study conducted at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Percent biomass reduction was calculated using the following equation:

![]() ${\rm Biomass reduction} (\,\%\,)={{\left( {\bar{C}{\minus}\left. B \right)} \right.} \over { \bar{C}}}{\times}100$

, where

${\rm Biomass reduction} (\,\%\,)={{\left( {\bar{C}{\minus}\left. B \right)} \right.} \over { \bar{C}}}{\times}100$

, where

![]() $\bar{C}$

is the mean biomass of the four non-treated control replicates, and B is the biomass of an individual treated experimental unit.

$\bar{C}$

is the mean biomass of the four non-treated control replicates, and B is the biomass of an individual treated experimental unit.

Table 3 Estimates of regression parameters and glyphosate dose required for 50% (ED50) and 90% (ED90) control of Palmer amaranth biotypes, 21 days after treatment, in a greenhouse whole-plant glyphosate dose-response study at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

a Abbreviations: ED50, effective glyphosate dose required to control 50% population at 21 days after treatment; ED90, effective glyphosate dose required to control 90% population at 21 days after treatment; S1, glyphosate-susceptible Palmer amaranth biotype collected from a field in Buffalo County, NE; S2, glyphosate-susceptible Palmer amaranth biotype collected from a field in Fillmore County, NE; R, glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth biotype collected from a field in Thayer County, NE; SE, standard error.

b Regression parameters b and d of three-parameter log-logistic model were obtained using the nonlinear least-square function of the statistical software R.

c Resistance level was calculated by dividing the ED90 value of the resistant Palmer amaranth biotype by that of the susceptible Palmer amaranth biotypes (S1 and S2). A range of resistance levels is provided due to a difference in ED90 values for S1 and S2.

Dose-response curves for GR Palmer amaranth biomass reduction indicated similar levels of resistance (35- to 36-fold) indicated by ED90 values based on visual control scores (Figure 2, Table 4). GR Palmer amaranth biomass was reduced to 50% and 90% at 1,319 and 16,797 g ha–1 glyphosate rates, respectively (Table 4). Similarly, Nandula et al. (Reference Nandula, Reddy, Kroger, Poston, Rimando, Duke, Bond and Ribeiro2012) observed a 50% biomass reduction of two GR biotypes from Mississippi with glyphosate applied at 1,520 and 1,300 g ha–1. In contrast, Mohseni-Moghadam et al. (Reference Mohseni-Moghadam, Schroeder, Heerema and Ashigh2013b) reported 50% biomass reduction of a GR Palmer amaranth biotype from New Mexico with glyphosate applied at 458 g ha−1, about 2.9-fold lower application rate than the level observed in this study.

Table 4 Estimates of regression parameters and glyphosate dose required for 50% (ED50) and 90% (ED90) aboveground biomass reduction of Palmer amaranth biotypes, 21 days after treatment, in a greenhouse whole-plant glyphosate dose-response study at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

a Abbreviations: ED50, effective glyphosate dose required for 50% reduction of dry shoot biomass of Palmer amaranth biotypes at 21 d after treatment; ED90, effective dose required for 90% reduction of dry shoot biomass of Palmer amaranth biotypes at 21 d after treatment; S1, glyphosate-susceptible Palmer amaranth biotype collected from a field in Buffalo County, NE; S2, glyphosate-susceptible Palmer amaranth biotype collected from a field in Fillmore County, NE; R, glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth biotype collected from a field in Thayer County, NE; SE, standard error.

b Regression parameters b and d of three-parameter log-logistic model were obtained using the nonlinear least-square function of the statistical software R.

c Resistance level was calculated by dividing the ED90 value of the resistant Palmer amaranth biotype by that of susceptible Palmer amaranth biotypes (S1 and S2). A range of resistance levels is provided due to a difference in ED90 values for S1 and S2.

EPSPS Gene Amplification

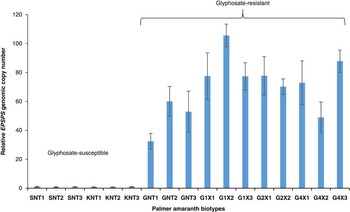

In the current study, the EPSPS copy number in Palmer amaranth was measured relative to two known glyphosate susceptible populations from Buffalo County and Fillmore County, NE (S1 and S2, respectively) using β-tubulin as a reference gene. EPSPS gene copy numbers ranging from 32 (GNT1, non-treated suspected GR biotype) to 105 (G1X2, suspected GR biotype survived treatment with 1x glyphosate rate) were found in Palmer amaranth plants that survived glyphosate application (Figure 3), suggesting that amplification of the EPSPS gene contributes to glyphosate resistance in the Palmer amaranth biotype from Nebraska. Similar to the GR Palmer amaranth biotype from Georgia (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Shaner, Ward, Leach, Preston and Westra2011), Palmer amaranth plants that had >30 EPSPS copies were able to survive and confer resistance to the label-recommended rate of glyphosate. More recently, GR Palmer amaranth from Kansas was also found to have 50 to 140 EPSPS copies (Varanasi et al. Reference Varanasi, Betha, Thompson and Jugulam2015), and a biotype from New Mexico with 6 to 8 EPSPS copies survived treatment with the labeled rate of glyphosate (Mohseni-Moghadam et al. Reference Mohseni-Moghadam, Schroeder and Ashigh2013a). EPSPS gene amplification also contributes to glyphosate resistance in other members of the Amaranthaceae family; for example, Nandula et al. (Reference Nandula, Wright, Bond, Ray, Eubank and Molin2014) reported 33 to 37 copies of the EPSPS gene in GR spiny amaranth (Amaranthus spinosus L.) from Mississippi. In a multistate study, 4 to 10 EPSPS gene copies were reported in several populations of GR common waterhemp [Amaranthus tuberculatus (Moq.) Sauer] collected from several states in the Midwest (Chatham et al. Reference Chatham, Bradley, Kruger, Martin, Owen, Peterson, Mithila and Tranel2015a). Similarly, Sarangi (Reference Sarangi2016) reported an average of 5.3 EPSPS gene copies in a GR common waterhemp biotype from Nebraska. These reports suggest that EPSPS gene amplification is a common glyphosate resistance mechanism in Amaranthaceae.

Figure 3 The EPSPS gene copy numbers of glyphosate-resistant and glyphosate-susceptible Palmer amaranth biotypes, relative to susceptible samples. Biotypes SNT1, SNT2, SNT3, KNT1, KNT2, and KNT3 were glyphosate-susceptible. Biotypes G1x1, G1x2, and G1x3 survived treatment with 1×glyphosate (870 g ae ha−1), biotypes G2x1 and G2x2 survived treatment with 2×glyphosate, and biotypes G4x1, G4x2, and G4x3 survived treatment with 4× glyphosate. Sample SNT1, which has a single copy of the EPSPS gene, was used as a calibrator for determining the relative ESPSP gene copy numbers. Error bars represent the standard error from the mean (n=3 technical replicates). The qPCR data were normalized using β-tubulin as a reference gene. Abbreviations: EPSPS, 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate; GNT, glyphosate non-treated suspected glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth plant samples from Thayer county, NE; KNT, glyphosate non-treated glyphosate-susceptible Palmer amaranth plant samples collected from Buffalo County, NE; qPCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; SNT, glyphosate non-treated glyphosate-susceptible Palmer amaranth plant samples collected from Fillmore County, NE.

Response to POST Corn Herbicides

Experiment by treatment interactions for Palmer amaranth control (P=0.09) and biomass reduction (P=0.102) in response to corn herbicides were not significant; therefore, data from both experiments were combined. The GR Palmer amaranth biotype was very sensitive to glufosinate, which provided 90% and 99% control at 7 and 21 DAT, respectively. Similarly, previous studies have reported >95% Palmer amaranth control with glufosinate (Jhala et al. Reference Jhala, Sandell, Rana, Kruger and Knezevic2014; Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Griffith, Scott, Smith and Oliver2008; Salas et al. Reference Salas, Burgos, Tranel, Singh, Glasgow, Scott and Nichols2016). At 21 DAT, dicamba and 2,4-D ester, applied alone, controlled Palmer amaranth 81% and 74%, respectively, and a 2,4-D choline plus glyphosate premix formulated for 2,4-D plus glyphosate–tolerant corn and soybean provided 89% control. Craigmyle et al. (Reference Craigmyle, Ellis and Bradley2013) reported 97% control of 10 to 15 cm tall common waterhemp, a species closely related to Palmer amaranth, with tank-mixed application of glufosinate and 2,4-D choline at 450 and 840 g ae ha–1, respectively, in 2,4-D plus glufosinate–tolerant soybean. Jhala et al. (Reference Jhala, Sandell, Rana, Kruger and Knezevic2014) have further reported 83% to 97% control of three Palmer amaranth biotypes with dicamba or 2,4-D ester applied at 560 g ae ha–1. Similarly, Norsworthy et al. (Reference Norsworthy, Griffith, Scott, Smith and Oliver2008) reported >95% control of GR palmer amaranth with dicamba and 2,4-D amine applied alone at 280 and 560 g ha–1, respectively; however, the reduced control (74%) of GR Palmer amaranth with 2,4-D ester in this study might be due to the use of the lowest label-recommended rate (386 g ha–1).

At 7 and 21 DAT, HPPD-inhibiting herbicides (mesotrione, topramezone, and tembotrione, used individually) failed to control GR Palmer amaranth (≤60%). Control was not improved with premixed applications of tembotrione and thiencarbazone (51%), or with mesotrione plus S-metolachlor plus glyphosate (33%) at 21 DAT. Jhala et al. (Reference Jhala, Sandell, Rana, Kruger and Knezevic2014) also reported 55% to 75% control of HPPD- and PSII-inhibitor-resistant Palmer amaranth and ≥84% control of two susceptible Palmer amaranth biotypes from Nebraska with POST application of mesotrione or topramezone at rates similar to those tested in this study (105 and 18.4 g ai ha–1, respectively). Similarly, Norsworthy et al. (Reference Norsworthy, Griffith, Scott, Smith and Oliver2008) reported ≥79% control of GR and GS Palmer amaranth biotypes from Arkansas in a greenhouse study with a POST application of mesotrione at 105 g ha–1.

At 7 and 21 DAT, PSII-inhibitors (atrazine or bromoxynil) controlled GR Palmer amaranth ≤25% (Table 5). In contrast, previous studies reported 100% control of glyphosate- and PPO-inhibitor-resistant Palmer amaranth biotypes from Arkansas with a POST application of atrazine at the rates tested in this study (2,240 g ha–1) (Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Griffith, Scott, Smith and Oliver2008; Salas et al. Reference Salas, Burgos, Tranel, Singh, Glasgow, Scott and Nichols2016). Jhala et al. (Reference Jhala, Sandell, Rana, Kruger and Knezevic2014) reported <25% control of HPPD- and PSII-inhibitor-resistant Palmer amaranth and 45% to 75% control of two susceptible Palmer amaranth biotypes from Nebraska with atrazine applied at 560 g ai ha–1. Bromoxynil is not very effective for Palmer amaranth control; for instance, Corbett et al. (Reference Corbett, Askew, Thomas and Wilcut2004) reported <60% control of 8 to 10 cm tall Palmer amaranth with bromoxynil applied at 420 g ae ha–1, twice the rate used in this study. At 7 DAT, carfentrazone-ethyl and fluthiacet-methyl (PPO-inhibitors) controlled Palmer amaranth <60%; however, control decreased to ≤30% at 21 DAT. In contrast, Jhala et al. (Reference Jhala, Sandell, Rana, Kruger and Knezevic2014) observed variable control of three Palmer amaranth biotypes (38% to 95%) at 21 DAT with fluthiacet-methyl at 7.2 g ai ha–1 in a greenhouse study, providing evidence for the reduced sensitivity of GR Palmer amaranth biotypes to PPO-inhibitors. Reddy et al. (Reference Reddy, Stahlman, Geier, Bean and Dozier2014) also reported 55% to 96% control of three Palmer amaranth biotypes at 21 DAT with fluthiacet-methyl and carfentrazone at rates used in this study (7.2 and 8.8 g ai ha–1, respectively). GR Palmer amaranth was <20% controlled at 21 DAT by halosulfuron-methyl, one of the ALS inhibitors, which is not surprising given that ALS-inhibitor-resistant weeds have become widespread in the Midwest due to the continuous use of ALS-inhibiting herbicides in corn and soybean (Heap Reference Heap2016b; Sarangi et al. Reference Sarangi, Sandell, Knezevic, Aulakh, Lindquist, Irmak and Jhala2015). Glyphosate applied alone controlled Palmer amaranth ≤30% as observed in the glyphosate dose-response study.

Table 5 Effects of POST corn herbicide treatments on glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth control 7 and 21 days after treatment (DAT), and biomass reduction 21 DAT.

a Ammonium sulfate (DSM Chemicals North America Inc., Augusta, GA) at 2.5% wt/v was added to all herbicide treatments except carfentrazone-ethyl; nonionic surfactant (Induce®, Helena Chemical Co., Collierville, TN) at 0.25% v/v was added to 2,4-D, bromoxynil, S-metolachlor+mesotrione+glyphosate, and glyphosate treatments; crop oil concentrate (Agridex®, Helena Chemical Co., Collierville, TN) at 1% v/v was added to atrazine, carfentrazone-ethyl, mesotrione, thiencarbazone+tembotrione, dicamba, halosulfuron-methyl, and fluthiacet-methyl treatments; and methylated seed oil (Southern Ag Inc., Suwanee, GA) at 1% v/v was added to topramezone and tembotrione treatments.

b Means within columns with no common letter(s) are significantly different according to Fisher’s protected LSD test where P≤0.05.

c

Percent control and biomass reduction data of non-treated control were not included in analysis. Biomass reduction was calculated based on comparison with the average biomass of the non-treated control using the following equation:

![]() ${\rm Biomass reduction }({\rm \,\%\,})={{\left( {\bar{C}{\minus}\left. B \right)} \right.} \over { \bar{C}}}{\times}100$

, where

${\rm Biomass reduction }({\rm \,\%\,})={{\left( {\bar{C}{\minus}\left. B \right)} \right.} \over { \bar{C}}}{\times}100$

, where

![]() $\bar{C}$

is the mean biomass of the four non-treated control replicates and B is the biomass of an individual treated experimental unit.

$\bar{C}$

is the mean biomass of the four non-treated control replicates and B is the biomass of an individual treated experimental unit.

Results of the control scores were reflected in biomass reduction of GR Palmer amaranth. For example, glufosinate resulted in the highest biomass reduction (99%), which was comparable with 2,4-D choline plus glyphosate (92%), and dicamba (87%). All other treatments resulted in 15% to 80% biomass reduction. Similarly, Mohseni-Moghadam et al. (Reference Mohseni-Moghadam, Schroeder, Heerema and Ashigh2013b) reported no difference in biomass reduction of two Palmer amaranth biotypes at 16 DAT with glufosinate (>97%) or dicamba (88%) applied POST. Likewise, Jhala et al. (Reference Jhala, Sandell, Rana, Kruger and Knezevic2014) reported <80% biomass reduction of HPPD- and PSII-inhibitor-resistant Palmer amaranth with mesotrione, topramezone, atrazine, halosulfuron-methyl, fluthiacet-methyl, or bromoxynil applied POST at 21 DAT.

Response to POST Soybean Herbicides

Experiment by treatment interactions for Palmer amaranth control (P=0.15) and biomass reduction (P=0.102) in response to soybean herbicides were not significant; therefore, data from both experiments were combined. At 21 DAT, GR Palmer amaranth was controlled 20% to 40% with ALS-inhibitors (chlorimuron-ethyl, imazethapyr, thifensulfuron-methyl, and Imazamox) and control (23% to 36%) was not improved with a premix of imazethapyr plus glyphosate or chlorimuron plus thifensulfuron-methyl (Table 6). In contrast, previous studies have reported >80% Palmer amaranth control with imazethapyr or thifensulfuron-methyl at 21 DAT at the rates tested in this study (Horak and Peterson Reference Horak and Peterson1995; Sweat et al. Reference Sweat, Horak, Peterson, Lloyd and Boyer1998). Gossett and Toler (Reference Gossett and Toler1999) also reported 69% Palmer amaranth control with chlorimuron-ethyl applied at a rate (9 g ha−1) lower than that tested in this study (13 g ha−1).

Table 6 Effects of POST soybean herbicide treatments on glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth control 7 and 21 days after treatment (DAT), and biomass reduction at 21 DAT.

a Ammonium sulfate (DSM Chemicals North America Inc., Augusta, GA) at 2.5% wt/v was added to all herbicide treatments except glyphosate+dicamba and acetochlor+fomesafen; nonionic surfactant (Induce®, Helena Chemical Co., Collierville, TN) at 0.25% v/v was added to all herbicide treatments except glyphosate+dicamba, glyphosate+2,4-D choline, and dicamba. MON 10 (Monsanto Company, 800 North Lindberg Ave., St. Louis, MO) was mixed at 2% v/v with glyphosate+dicamba.

b Means within columns with no common letter(s) are significantly different according to Fisher’s protected LSD test where P≤0.05.

c

Percent control and biomass reduction data of non-treated control were not included in analysis. Biomass reduction was calculated based on comparison with the average biomass of the non-treated control using the following equation:

![]() ${\rm Biomass reduction} (\,\%\,)={{\left( {\bar{C}{\minus}\left. B \right)} \right.} \over { \bar{C}}}{\times}100$

, where

${\rm Biomass reduction} (\,\%\,)={{\left( {\bar{C}{\minus}\left. B \right)} \right.} \over { \bar{C}}}{\times}100$

, where

![]() $\bar{C}$

is the mean biomass of the four non-treated control replicates and B is the biomass of an individual treated experimental unit.

$\bar{C}$

is the mean biomass of the four non-treated control replicates and B is the biomass of an individual treated experimental unit.

The PPO-inhibitors lactofen and acifluorfen controlled Palmer amaranth 55% at 7 DAT and control decreased to <50% at 21 DAT. In contrast, previous studies have reported 60% to 81% Palmer amaranth control with acifluorfen applied at a lower rate (280 g ha−1) than that used in this study, and 85% to 99% control with lactofen applied at rates similar to those tested in this study (220 g ha−1) (Gossett and Toler Reference Gossett and Toler1999; Jhala et al. Reference Jhala, Sandell, Rana, Kruger and Knezevic2014; Sweat et al. Reference Sweat, Horak, Peterson, Lloyd and Boyer1998). Aulakh et al. (Reference Aulakh, Chahal and Jhala2016) further reported complete control of common waterhemp with acifluorfen and lactofen (420 and 220 g ha−1, respectively) applied in a greenhouse study at rates similar to those tested here. Fomesafen, another PPO-inhibitor, controlled Palmer amaranth 69% and 72% at 7 and 21 DAT, respectively. Likewise, Sweat et al. (Reference Sweat, Horak, Peterson, Lloyd and Boyer1998) reported 74% to 83% Palmer amaranth control with fomesafen applied in both field and greenhouse studies at the same rate tested in this study (280 g ha−1). In contrast, Merchant et al. (Reference Merchant, Culpepper, Eure, Richburg and Braxton2014) reported 89% to 99% Palmer amaranth control at 15 DAT in a field study with fomesafen applied at rate similar to that tested in this study. This study showed poor control with premix applications of fomesafen with acetochlor (43%), glyphosate (62%), or fluthiacet-methyl (67%) at 21 DAT (Table 6).

Bentazon, a PSII-inhibitor, controlled Palmer amaranth <15% at 21 DAT. Similarly, previous studies have reported poor efficacy (<40%) of bentazon for control of spiny amaranth and Palmer amaranth (Grichar Reference Grichar1994, Reference Grichar1997). At 21 DAT, glufosinate, glyphosate plus 2,4-D choline, dicamba, or fomesafen provided 71% to 92% GR Palmer amaranth control. Control scores of GR Palmer amaranth were reflected in the biomass reduction results: glufosinate resulted in the highest Palmer amaranth biomass reduction (95%), and similar biomass reductions were seen with glyphosate plus 2,4-D choline (88%), dicamba plus glyphosate (76%), dicamba (73%), and fluthiacet plus fomesafen (71%). All other treatments resulted in 20% to 65% biomass reduction (Table 6).

Practical Implications

The putative GR Palmer amaranth biotype from Thayer County in Nebraska is GR with the level of resistance in the range of 35- to 40-fold compared to the GS Palmer amaranth biotypes. The evolution of GR Palmer amaranth in south-central Nebraska provides cause for concern, considering that glyphosate is the most common herbicide used for weed control in GR corn–soybean cropping systems. While GR Palmer amaranth has been reported in west-central Nebraska, the evolution of GR Palmer amaranth in south-central Nebraska will add management challenges for growers because GR common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.), common waterhemp, giant ragweed (Ambrosia trifida L.), horseweed [Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronq.], and kochia [Kochia scoparia (L.) Schrad.] are already present in the area.

A rapid molecular test, EPSPS gene amplification, has been identified to confirm glyphosate resistance in weeds and has been tested in a Palmer amaranth biotype from Georgia (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Zhang, Wang, Bukun, Chisholm, Shaner, Nissen, Patzoldt, Tranel, Culpepper, Grey, Webster, Vencill, Sammons, Jiang, Preston, Leach and Westra2010), populations of waterhemp from Illinois (Chatham et al. Reference Chatham, Wu, Riggins, Hager, Young, Roskamp and Tranel2015b), and GR waterhemp populations from several states in the Midwest (Chatham et al. Reference Chatham, Bradley, Kruger, Martin, Owen, Peterson, Mithila and Tranel2015a). The molecular test confirmed that the putative GR Palmer amaranth from south-central Nebraska acquired resistance by amplifying the EPSPS gene copy number; however, more research is needed to determine whether other mechanisms of resistance are involved.

The response of the GR Palmer amaranth biotype to POST corn and soybean herbicides suggests that control options are limited. Glufosinate was effective, providing >95% control of GR Palmer amaranth, but glufosinate can only be used in glufosinate-tolerant crops. While glufosinate-tolerant corn and soybean are available in the marketplace, current adoption of glufosinate-resistant soybean is limited in Nebraska (Aulakh and Jhala Reference Aulakh and Jhala2015; Chahal and Jhala Reference Chahal and Jhala2015). Additionally, the reduced sensitivity of GR Palmer amaranth to PSII- (atrazine), HPPD- (mesotrione, tembotrione, and topramezone), ALS- (halosulfuron-methyl), and PPO- (carfentrazone and lactofen) inhibitors justifies the need to conduct a whole-plant dose-response bioassay to confirm and determine the level of multiple resistance (if any) of this biotype to herbicides with these modes of action.