1. Introduction

In scholarship and in policy, there has often been a tendency to separate issue areas such as economics and security due to the nature of academic specialization as well as the bureaucratic processes of policymaking. When attention has been paid to the impacts of economics on security specifically, some have highlighted the vulnerability created by asymmetric economic relations (e.g., Hirschman, Reference Hirschman1945), but much scholarship in recent decades has posited a positive relationship, suggesting that economic interdependence would foster a ‘commercial peace’ between states (Oneal and Russett, Reference Oishi and Furuoka1997; Mansfield and Pevehouse, Reference Mansfield and Pevehouse2000; Hegre et al., Reference Hegre, Oneal and Russett2010). Economic ties have been hypothesized to constrain state behavior by increasing the costs associated with armed conflict, by making it easier for states to signal resolve, and by reshaping state interests, for example (Polachek, Reference Pekkanen and Kallender-Umezu1980; Solingen, Reference Soeya1998; Gartzke et al., Reference Gartzke, Li and Boehmer2001; Kahler and Kastner, Reference Kahler and Kastner2006; Dafoe and Kelsey, Reference Dafoe and Kelsey2014). Though these claims have been disputed, similar logics have also informed US foreign policy toward a rising China, contributing to successive US administrations adopting economic engagement as a key element of their approach, with the aim of socializing China into peaceful integration with the existing international order.

However, recent years have upended expectations that deepening economic interdependence would lead to increasingly tranquil interstate relations. Indeed, under the Trump administration, trade issues have emerged as a central source of political conflict on the international stage. Nowhere has this been more pronounced than in the intensifying strategic competition between the US and China, which has led to a prolonged trade war and to predictions of potential economic decoupling between the world's two largest economies. Escalating US–China tensions have affected countries around the world and the international system itself, disrupting not only economic relations but also other issue domains.

This reemergence of strategic competition and trade war has led to renewed interest in ‘economic statecraft’, the use of economic tools as means to non-economic ends (Baldwin, Reference Baldwin1985). As states have become increasingly economically integrated with one another, these burgeoning connections have not only had economic impacts; they have also expanded the available opportunities for states to intentionally manipulate economic levers to attempt to influence other issue domains. States may choose to do this in a positive way, to reward or incentivize desirable behavior, or as we have seen more often in recent years, they may take negative actions to punish others using sanctions or other restrictions. Many analysts noted China's increasing use of economic coercion throughout the 2000s and 2010s, for example, to punish states for opposing Chinese policy in the South China Sea and for taking undesirable actions such as the deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system by South Korea (Blackwill and Harris, Reference Blackwill and Harris2016; Norris, Reference Noland2016; Li, Reference Li2017; Harrell et al., Reference Harrell, Rosenberg and Saravalle2018; Yang and Liang, Reference Yamamoto, Asplund and Soderberg2019). However, a significant turning point in international dynamics came with the election of Donald Trump in 2016. In contrast to previous US strategy of using broad linkages to economics to reinforce its political and military relationships (Calder, Reference Calder2004) and levying targeted economic sanctions against countries in specific situations, US policy under the Trump administration has been characterized by the use of economic leverage to extract concessions across a wide array of security and economic issues. This has included the use of sanctions and economic pressure against a large number of countries, extending beyond China to include even traditional US security allies (Drezner, Reference Drezner2019).

Although studies of economic statecraft are rapidly proliferating, with a few notable exceptions (e.g., Armijo and Katada, Reference Armijo and Katada2014; Thurbon and Weiss, Reference Takenaka2019; Katada, Reference Katada2020), they have tended to limit their scope to the actions of great powers, underemphasizing the important role that middle and smaller states play in shaping the international system (Tiberghien, Reference Thurbon and Weiss2013; Ikenberry, Reference Ikenberry2016) and potentially leading to the incorrect conclusion that economic statecraft is only the preserve of the powerful. This article contributes to theory building about the use of economic statecraft by middle powers by examining Japan's adaptation of economic statecraft from the end of World War II to the present, with particular attention to the period following the emergence of US–China strategic competition. Although the definition of ‘middle power’ has been the subject of much debate, the term has generally been applied to states weaker than the great powers in the system but among the top 20–30 most powerful countries in the world (Carr, Reference Carr2014; Walton and Wilkins, Reference Wallace2019). Japan has long been discussed as a middle power based on multiple standards such as position, behavior, identity, and systemic impact (e.g., Cox, Reference Cox1989; Soeya, Reference Seawright and Gerring2005). Moreover, Japan is an instructive case in which to examine the use of economic statecraft due to its unusual political constraints. After its devastating defeat in World War II, Japan formally renounced its right to war and threat or use of force in Article 9 of its constitution. While this verbiage was gradually reinterpreted to allow the country to maintain forces for its self-defense, this situation endowed economic policy with a particular prominence in Japanese foreign affairs, lending it characteristics of an ‘extreme case’ that make it particularly fruitful for an exploratory probe of the processes of economic statecraft (Seawright and Gerring, Reference Sasada2008).

How has Japan wielded economic statecraft? This article tackles this question through case studies of three different tools of Japanese economic statecraft: trade arrangements, official development assistance, and dual-use technology. These cases were selected because these tools fall under more direct government control than other instruments that rely more heavily on the cooperation of commercial actors; thus, they can be thought to reflect Japanese strategic intent with relative clarity. This article argues that Japan has adapted these tools of economic statecraft throughout the post-World War II period in response to changing conditions and strategic aims. From the 1950s to the 1990s, Japan's use of these economic tools served goals such as reintegrating into the international system, as well as addressing Japan's concerns about first ‘comprehensive security’ and later ‘human security’. In response to the rise of China in the 2000s and the escalation of US–China strategic competition in the 2010s, Japan has adapted its economic statecraft to attempt to stabilize the international order and to counter China in targeted ways that reflect more traditional security considerations as well. First, Japan has attempted to bolster multilateral trade arrangements amid a volatile policy environment, while also using them to both engage and counter China. Second, Japan has responded to expanding Chinese influence in the region by using its official development assistance to stabilize and build defense capacity in Asian countries facing pressure from China. Third, increasing competition from China in outer space has led Japan to militarize its substantial suite of dual-use technologies, quietly augmenting its capabilities in ways that have strategic relevance for the Japan's security on Earth as well.

This article makes several contributions to the existing literature. First, it refutes the notions that economic statecraft is limited to great powers or that it is a relatively new phenomenon that has emerged only in response to US–China competition, instead demonstrating that Japan has used economic statecraft continuously over the post-World War II period to achieve its changing strategic aims. This advances theory building about how the use of economic statecraft may vary across different types of states as well as across time. Second, while many studies have focused on economic sanctions as targeted, quantifiable forms of economic statecraft, this specificity has obscured the much more expansive role that economic policies play in states’ non-economic strategies. Instead, this article facilitates comparative analysis by examining a broader array of tools, demonstrating the variety and versatility of economic statecraft as well as the changing nature of the economic instruments at states’ disposal (Aggarwal and Reddie, Reference Aggarwal and Reddiethis issue). Third, this analysis contributes to a more nuanced understanding of international relations by illustrating how middle powers like Japan may influence the international system by addressing perceived threats or bolstering international institutions against instability. Particularly during periods of great power competition, middle and smaller states may have the ability to shift the regional or global order in favor of one side or the other, making it particularly important to understand their policies. Finally, this article sheds light on changing Japanese foreign policy, showing that while it has maintained strong ties with China in trade and investment, Japan has also simultaneously used economic tools to counter China in targeted ways. Thus, these manifestations of economic statecraft are nested within a broader hedging approach on the part of Japan, where hedging is defined as the pursuit of a set of mixed strategies aimed at reducing the risks associated with overt balancing or bandwagoning. In this context, economic statecraft is a particularly useful strategy because its tools are not necessarily obviously threatening, which reduces the danger that they will provoke a negative reaction from others.

The article proceeds by presenting the three case studies of trade arrangements, official development assistance, and dual-use technology. Each case study establishes a baseline for Japan's activities in the immediate post-World War II period and then traces key shifts over time. Particular attention is paid to the period following the rise of China and the emergence of US–China strategic competition, in response to which Japan adapts its use of each of these tools to address this new international context. The conclusion builds on the findings of the individual case studies to offer a comparative analysis of the three tools and to suggest potential implications for our understanding of the economic statecraft of middle powers.

2. Supporting Global and Regional Trade Arrangements

This section demonstrates how Japan has adapted its approach to global and regional trade arrangements in response to changing strategic interests. Japan's goals for these arrangements in the decades following World War II extended beyond their immediate trade benefits to include helping it to reintegrate with the international order, deflect US trade pressure, and pursue comprehensive security goals. With respect to the period following the rise of China and the emergence of US–China competition, Japan's initial support of the Trans-Pacific Partnership reflected in part its increasing security concerns about China. After the US withdrawal from the agreement, Japan's continued advocacy for TPP was motivated by a desire to support the multilateral trading system, as well as to preserve the opportunity for the US to potentially rejoin the agreement at a later date.

An early post-World War II application of Japanese economic statecraft came in the form of seeking admission to multilateral economic institutions as a means of global political reintegration. Japan had essentially become a pariah state due to its imperialist expansion across Asia, which led it to leave the League of Nations and sever ties with many other countries. Therefore, gaining entry to these institutions was important not only for their associated economic benefits but as a symbolic and functional return to the liberal international order. During and after World War II, the US, UK, and other allied countries negotiated to establish the rules for the global economy, creating the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank in 1944 and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947. To overcome domestic and international objections to Japan's membership, the US linked a liberal trade policy toward Japan to the need to contain Communism, since defense planners believed that transforming Japan into a strong anti-communist ally was essential to American Cold War strategy. US support paved the way for Japanese accession to the GATT in 1955 and its greater integration with the Western trading bloc (Forsberg, Reference Forsberg1996). The Japanese economy flourished in the decades that followed, leading some to argue that Japan was the prime beneficiary of the liberal international economic order during this period (Noland, Reference Nikitina and Furuoka2000). Japan came to view the stability of this order as essential to its economic well-being and therefore the foundation of its overall security.

However, Japan's economic success also led to international criticism over its slow and uneven liberalization and to escalating trade tensions with the US, which prompted Japan to adapt by actively embracing the World Trade Organization (WTO) after its creation in 1995. The WTO provided Japan and other middle and smaller states a way to push back against US pressure from a position of relative strength. They were able to marshal support from within this multilateral forum in a way that would have been impossible in a bilateral context (Pekkanen, Reference Otani and Kohtake2005). The broad-based multilateral negotiating framework also had domestic benefits, empowering Japanese trade negotiators against both foreign actors and domestic protectionist interests (Davis, Reference Davis2003). Japan's active approach to the WTO has also been reflected in its frequent use of the dispute resolution system. From 1995 to 2019, Japan initiated 26 disputes as a complainant and participated in 212 as a third party (World Trade Organization, Reference Walton, Wilkins, Struye de Swielande, Vandamme, Walton and Wilkins2019).

This support for the WTO has been paralleled at the regional level by Japan's participation in the ‘open regionalism’ model of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum, which Japan used to further both economic aims and broader goals related to ‘comprehensive security’. The term comprehensive security appeared in Japanese policy discourse in the late 1970s, signaling an expansive understanding of security beyond a focus on traditional military issues (Heiwamondai Kenkyukai, 1985). In particular, it reflected Japan's strong dependence on imported energy and worries about loss of access or price increases as occurred with petroleum during the 1970s. This concern with energy security has continued, and APEC presented Japan with an opportunity to pursue comprehensive security goals through its Energy Working Group, which has been among the most active of APEC's working groups. The forum has also engaged in energy-related information sharing, target setting, and introduction of an energy peer review mechanism (Ravenhill, Reference Polachek2013).

Japan continued to adapt its approach to trade arrangements as time went on, with a shift first to bilateral agreements in the early 2000s and then to ‘mega-regional’ arrangements in the late 2000s. These changes in instruments were prompted by economic conditions initially, with the stalling of the WTO's Doha Round leading many countries to pursue liberalization in targeted areas with specific partners; however, these smaller trade arrangements were also potential tools of economic statecraft, with security motivations playing a role in driving the formation of some agreements (Aggarwal and Govella, Reference Aggarwal, Govella, Aggarwal and Govella2013). Japan was initially slow to jump on the bilateral bandwagon due to its preference for the WTO as well as its domestic protectionist constituencies, but Japan signed its first bilateral preferential trade agreement with Singapore in 2002 and went on to ink agreements with 14 countries and ASEAN by 2017.

However, as the difficulties of harmonizing the ‘noodle bowl’ of complex bilateral PTAs became obvious, countries turned to mega-regional trade agreements, which the United States in particular spearheaded as vehicles through which to ‘write the rules’ of free trade (e.g., Obama, Reference Norris2015) as well as to accomplish non-economic strategic objectives. The mega-regional Trans-Pacific Partnership was strongly framed in security terms by the Obama administration as part of its ‘rebalance’ to Asia, depicted as both an important pillar of American economic engagement with Asia and as a mechanism to counter rising Chinese influence in the region. Although the Obama administration also tried to engage China economically, the security dimension of TPP was often quite blatant, as when US Secretary of Defense Ash Carter stated that ‘TPP was as important to [him] as another aircraft carrier’ (Carter, Reference Carter2015). In China, many initially perceived the trade agreement to be part of a containment strategy (Song and Yuan, Reference Solis2012), though China later expressed interest in joining the agreement (Cheng and Lee, Reference Cheng, Lee and Chow2016). Although China was technically eligible for TPP membership, the focus on achieving a high-quality agreement presented a practical barrier to its participation. This allowed the US to institutionalize its preference for more stringent terms of trade while simultaneously building ties to a group of countries that shared concerns about China's increasing influence. For example, Bhala (Reference Bhala2017) argues that disagreements over the definition of terms such as ‘state-owned enterprise’ provide evidence of the interconnection between trade, national security, and containment in TPP's formation; the agreement excluded China becoming a founding signatory on the basis of such distinctions and was structured to bind China if it subsequently joined the deal.

Japan's thinking about TPP was also strongly influenced by the rise of China and increasing tensions with its neighbor. Anti-Japanese protests and lingering historical issues shook the Sino-Japanese relationship in the 2000s, and a set of developments involving the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the early 2010s sunk bilateral relations to new lows. There was widespread recognition in Japan of TPP's geopolitical and security implications vis-à-vis China. Though these elements were less overtly emphasized in Japan's policy discourse than they were in the US, TPP and security were linked in the minds of Japanese policymakers (Mulgan, Reference Govella2016). These strategic considerations, the long continuity of leadership under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, and the weakening of protectionist interests such as agricultural cooperatives enabled Japan to overcome its customary reticence about free trade to join the TPP negotiations in 2012, eventually signing the agreement in 2016 (Solis, Reference Solingen2017). With the accession of Japan, the agreement was set to cover roughly 40% of world GDP and one-third of world trade.

As US support for TPP began to waver due to domestic politicization in 2016, Japan quickly adapted to become one of the pact's strongest advocates. Immediately after the 2016 US election, Prime Minister Abe tried to encourage then-President-elect Trump to reverse his well-known opposition to TPP, saying that the agreement would be ‘meaningless without the US’ (Takenaka, Reference Suzuki, Logsdon and Moltz2016). In January 2017, despite knowing that an American defection was probably imminent, Japan ratified the agreement as a sign of its own commitment. After the Trump administration formally made the decision to withdraw in January 2017, Japan actively fought to push the agreement forward with the remaining 11 members, countering proposals by countries such as Malaysia and Vietnam to reopen discussion on specific portions of the agreement. Japan also tried to forestall attempts by the remaining TPP members to follow the American turn toward bilateralism, rejecting the idea of a Japan–Canada pact, for example.

Japan's leadership reflected not only its desire for the economic benefits of TPP, which were lessened significantly by the withdrawal of the US, but also its desire to maintain the strategic benefits of the deal. In this sense, Japan employed its economic statecraft to act as a surrogate for the United States, keeping the agreement alive to fulfill all of the original economic, political, and security functions for which the two countries had originally intended it. Japanese action, along with the efforts and cooperation of other signatories, helped to shape the agreement into a new Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) that preserved the work of the preceding decade of negotiations and also made it possible for the US to easily rejoin (Govella, Reference Govella2017). Remaining members agreed to ‘freeze’ specific controversial clauses that had been added largely at the request of the United States and were no longer appealing without the lure of the American market, making it plausible to thaw out these clauses at a later date, presumably with minimal debate since they had already been agreed upon by all parties.

Japan also continues to attempt to use other pieces of regional trade architecture to promote both its economic interests and its political vision. For example, Japan is a party to negotiations on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), another regional agreement that would cover a third of world GDP if signed. Although RCEP is often criticized as a lower quality trade agreement than CPTPP, RCEP membership includes Asian countries such as China and South Korea, which are not part of CPTPP. RCEP and CPTPP together potentially form the basis of an emerging trade architecture for the Asian region – and notably, the United States is not a member of either. In contrast, Japan, as one of the seven members who are members of both agreements, is well positioned to influence the region should either pact grow and develop into something more substantial. Since China is a key Japanese trade partner, RCEP offers a means of strengthening Sino-Japanese economic relations at the same time as CPTPP presents a way to hedge against Chinese influence and promote other trade priorities. Japan has also tried to convince India to stay in RCEP despite its economic concerns; Japan sees RCEP as essential to incorporating India more broadly into regional institutional architecture. Particularly given the recent emphasis in the US and Japan on the Indo-Pacific’, India's participation is seen as vital to defining the region in such a way as to counter rising Chinese influence across the spheres of economics, politics, and security.

In summary, after World War II, Japan adapted its use of trade arrangements to pursue changing non-economic aims such as political reintegration and comprehensive security. Intensifying US–China trade tensions and decreased American support for the multilateral trade system led Japan to adapt trade arrangements to promote its interests vis-à-vis China and to cushion the sudden policy changes undertaken by the Trump administration. Japan has acted to preserve institutions that are consistent with traditional American foreign economic policy positions, essentially creating space for the US to return to these commitments in the future. More broadly, Japan has supported the multilateral trading system in line with its view that a stable international economic order is essential to its security, trying to forestall the emergence of tit-for-tat tariff retaliation that would harm the Japanese economy. In addition to pursuing regional initiatives such as the CPTPP, RCEP, and APEC, Japan has also continued to support the WTO, continually calling for the restoration of full functionality to its Appellate Body, which the US had crippled by blocking the appointment of new judges. In aggregate, these changes have transformed Japan from a relative laggard to a leader in the realm of trade policymaking as Japan has leveraged trade arrangements to support its economic, political, and security goals.

3. Securitizing Official Development Assistance

Official development assistance (ODA) has been a prominent part of Japan's economic statecraft since the end of World War II. Some claim that ODA may actually be Japan's most important tool of foreign policy writ large during this period (Kato, Reference Kato, Kato, Page and Shimomura2016). Japan has used ODA to bolster its relationships with countries around the world, and in particular, to rebuild and strengthen ties with its Asian neighbors. This section demonstrates how Japan has adapted its approach to ODA in response to its evolving national interests, using aid institutions to reintegrate into the international order immediately after World War II and then shifting its aid allocations to reflect changing notions of ‘comprehensive security’ as well as ‘human security’. Japan's application of ODA as a tool of economic statecraft has increasingly reflected its security concerns over time, a process that analysts have referred to as the ‘securitization’ of aid. These scholars use this term broadly to mean that security concerns and interests have affected the rationales, priorities, policies, and practices of donor countries; this can take the form of justifying aid in terms of security and allocating aid based on security priorities, for example (Brown and Grävingholt, Reference Brown and Grävingholt2010).Footnote 1 Since the intensification of US–China competition, Japan has adapted its use of ODA to reflect traditional security concerns about China by providing resources to partner countries facing pressure in the South China Sea and by expanding the scope of Japanese ODA to enable assistance to militaries for non-military purposes.

As in the case of trade, gaining membership in aid-related organizations was part of a political strategy to facilitate Japan's return to the liberal international order. Japan's participation in the Colombo Plan beginning in 1954 was an important step. Similarly, Japan joined the World Bank in 1952 and became a founding member of the International Financial Cooperation in 1956 and the International Development Association in 1961. Japan also played a large role in the creation and subsequent management of the Asian Development Bank beginning in 1965, which it viewed as both a reputational and strategic asset (Mattlin and Gaens, Reference Mattlin, Gaens, Wigell, Schlovin and Aaltola2019). War reparations were key to Japan's early reintegration with the international community. Reparations were directed through Japanese firms, who received yen payments from the Japanese government and sold goods and services to Southeast Asian countries, which also enabled these firms to gain access to these markets. In addition, Japan began to initiate other forms of economic engagement with the region such as ODA, beginning with its first yen loans to India in 1958. Economic and commercial interests played an important part in determining the nature and destination of Japanese ODA (Arase, Reference Arase1994). The initial focus of Japan's ODA policy was Southeast Asia, which supported American goals of stabilizing those nations and also benefited the Japanese economy by creating Southeast Asian export markets that were necessary to Japan's further development, such as in the heavy and chemical industries (Araki, Reference Araki2007).

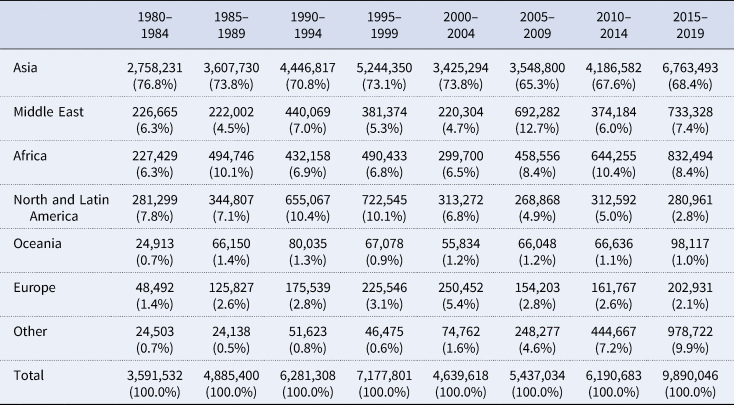

After the oil shocks of the 1970s, Japan adapted by shifting away from a narrow commercial focus in its ODA to more explicitly incorporate comprehensive security considerations such as energy. In the late 1970s, Japan expanded the geographic scope of its ODA beyond Southeast Asia to include places such as China, Egypt, Jamaica, Kenya, Somalia, South Korea, Sudan, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe in order to stabilize parts of the world that were essential to fueling Japanese economic networks and enable Japanese companies to secure access to energy supplies overseas (Yamamoto, 2016). ODA to China reflected the resumption of formerly robust economic ties between the two countries, enabled by their normalization of political relations. Japan's ODA was also adapted as a means of ‘burden sharing’ with the US, which meant that it was directed toward countries such as Pakistan, Thailand, and Turkey that were important partners in achieving American security objectives during the Cold War (Jain, Reference Jain, Kato, Page and Shimomura2016). However, Table 1 illustrates that Japan's ODA has always maintained a strong focus on Asia, reflecting the region's continuing strategic importance.

Table 1. Japanese ODA by Region (1980–2019, millions of yen and proportion of total aid)

Source: Compiled by author from Japan International Cooperation Agency (2019). Amounts shown are the total of loans, grants, and technical cooperation disbursed in each year.

In response to intensifying trade tensions with the US and demands for an increasingly wealthy Japan to do more in the international system, Japan doubled its total ODA budget, untied a greater proportion of its aid, and made its projects more widely accessible to companies from the US and other countries in the 1970s. Japanese ODA continued to expand throughout the 1980s, with Japan surpassing the US to become the top global ODA donor in 1989. Despite these achievements, Japan found itself subject to international criticism due to its rapid economic rise and its decision not to contribute troops to the Persian Gulf War. Japan released its first ODA charter in 1992 to articulate the value of its ODA programs to both domestic and international audiences. The charter also brought Japan into more direct compliance with norms in the international aid community on considerations related to human rights, democracy promotion, environmental practices, and market principles. Until this time, Japan had not used ODA for the purposes of political sanctions. It often refrained from implementing strongly negative policies against partners of strategic economic and diplomatic importance (Nikitina and Furuoka, Reference Mulgan2008).

Although Japan's ODA budget began to decline due to continuing economic difficulties after the bursting of its asset price bubble in the 1990s, Japan revised its ODA Charter in 2003 to emphasize a greater role for national interest in aid allocation and became the first country to fully commit to linking ‘human security’ to ODA. The concept of human security directs attention away from the traditional military state-centric view of security to encompass threats to individuals, promoting dimensions such as economic security, food security, health security, environment security, personal security, community security, and political security (United Nations Development Programme, Reference Tiberghien and Tiberghien1994). In reality, Japan had already been employing such practices in its ODA policy, but the 2003 charter explicitly connected humanitarian goals to ensuring Japan's security and prosperity (Kamidohzono et al., Reference Kamidohzono, Gomez, Mine, Kato, Page and Shimomura2016). To address human security, Japan adapted by increasing attention to the least developed countries in ASEAN – Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar – as well as to India. China was also a top destination for Japanese ODA from 1980 until the mid-2000s, after which time such aid was dramatically reduced and was then stopped entirely.

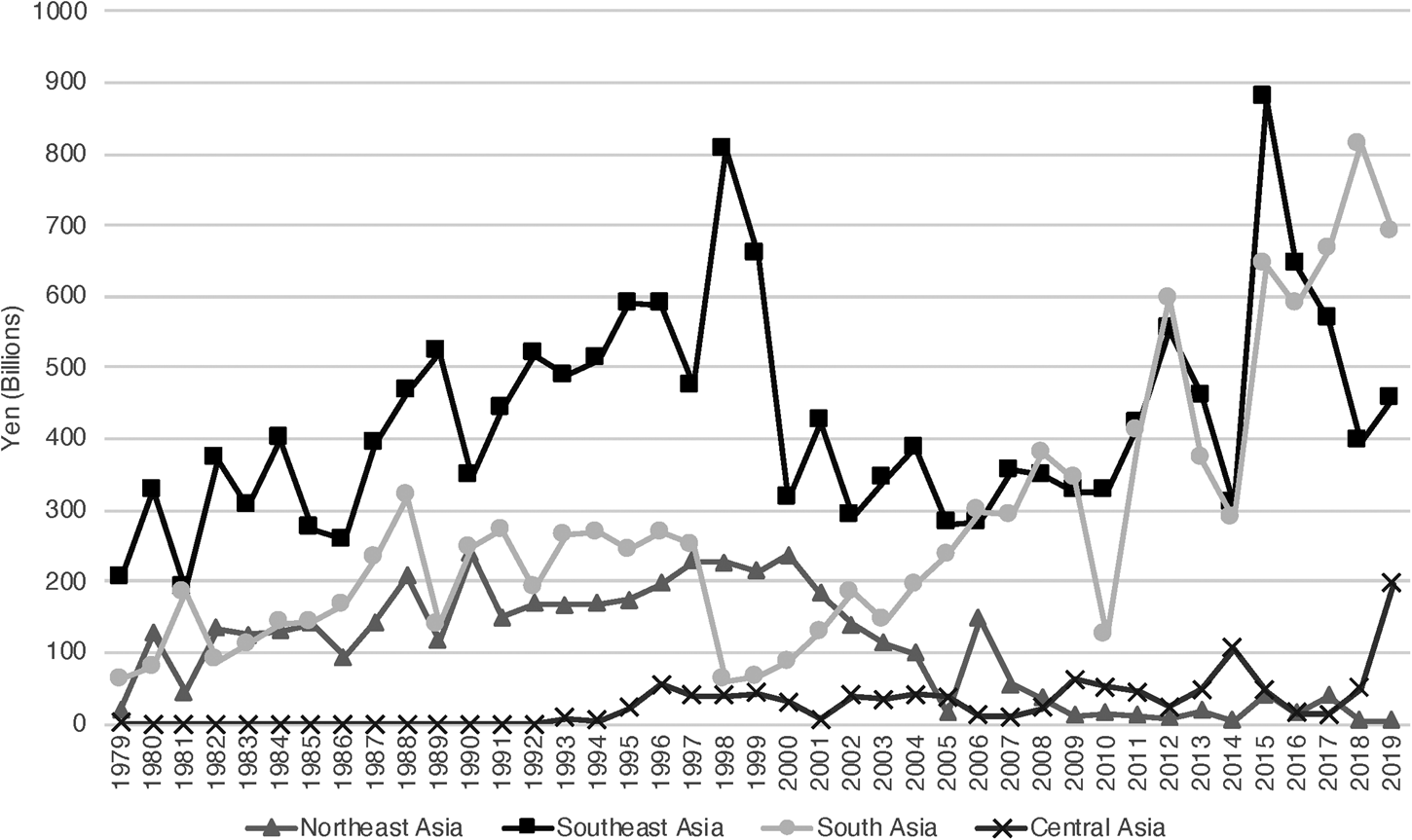

As the 2000s went on, growing worries about China's economic rise and its increasingly assertive security posture led Japan to again adapt its use of ODA as a tool of economic statecraft. These considerations led to further increases in ODA to South Asia, particularly India, and Southeast Asia. Figure 1 breaks down the sub-regional allocation of Japan's ODA, illustrating the growing importance of these two areas over time. ODA to India has been intended to solidify its relationship with Japan at a time when China's expansionist behavior has prompted shared concerns in the two countries. Aid programs have contributed to civil defense, sea lane security, and freedom of navigation in ways that are not explicitly military in nature but have clear consequences for countering rising Chinese influence. Japan began expanding its use of ODA for projects related to maritime security in the 2000s, providing grants to address non-traditional security threats like piracy, terrorism, and weapons proliferation to countries such as Indonesia, the Philippines, and Indonesia.

Figure 1. Japanese ODA to Asia by Sub-Region (1979–2019). Source: Compiled by author from Japan International Cooperation Agency (2019). Amounts shown are the total of loans, grants, and technical cooperation disbursed in each year.

Japan's use of ODA as a tool for security purposes became even more pronounced in the 2010s as tensions increased with China over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands and Chinese expansion in the South China Sea. Although Japan does not have a territorial claim in the South China Sea, developments there are perceived to be linked to Japanese national security due to its vital sea lines of communication in the area and the possibility that these activities might set a dangerous precedent for the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute in the East China Sea. These strategic considerations have led Japan to increasingly shift its ODA to Southeast Asia toward Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Myanmar (Jain, Reference Jain, Kato, Page and Shimomura2016). Japan has adapted its ODA to increase the capacity of its partner countries’ coast guards, which are important actors in territorial disputes because Chinese strategy often plays out in the realm of ‘gray zone conflict’ short of full-scale attack and relies heavily on paramilitary forces such as coast guards, militia, and fishermen (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy, Erickson and Martinson2019). Consequently, the Japan Coast Guard has been an important partner in these capacity building projects (Midford, Reference Midford2015). Training of law enforcement personnel in the region contributes to interoperability, and ODA has been used to dispatch Japanese experts to assess maritime law enforcement agencies in the region and to improve their capacities (Yamamoto, 2016). In addition to security concerns about China, considerations about China's increasing economic influence in Vietnam and Myanmar have also led Japan to focus more strongly on these countries (Oishi and Furuoka, Reference Obama2003; Jain, Reference Jain, Kato, Page and Shimomura2016).

These changes were further codified and expanded with changes under the Abe administration. After taking office in December 2012, Abe took steps to centralize and articulate security policy through a creation of a National Security Council and Japan's first-ever National Security Strategy. These changes have made it easier for the Japanese government to coordinate security policies across multiple domains in an intentional manner. The 2013 National Security Strategy explicitly links strategic use of ODA to not only human security but also to assistance in security-related areas that promote international peace cooperation and ensure the country's survival. This umbrella covers Japan's current initiatives to counter perceived Chinese assertiveness. As described above, a precedent already existed for ‘quasi-military’ use of economic assistance, but the Abe administration solidified these moves by lifting the ban on arms exports in 2014, which eased the process of transferring military equipment to other countries (Yamamoto, 2016). The Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics Agency (ATLA) was established in 2015, bringing together bureaucrats working on defense research and development, procurement, and exports. Japan also released a new Development Cooperation Charter in 2015, which explicitly allows economic aid to militaries for non-military purposes. This has resulted in a number of legal agreements for the transfer of military technologies and equipment to Southeast Asian countries for maritime domain awareness and transfers of equipment to countries such as the Philippines (Wallace, 2018). The 2015 charter also makes it clear that Japan will take a more proactive role in holding dialogue with its partner countries, in contrast to its previous approach of waiting until requests are made (Kato, Reference Kato, Kato, Page and Shimomura2016).

More broadly, Japan has reemphasized infrastructure investment in its ODA projects in Asia in recognition of rising regional demand, potential benefits for the Japanese economy, and increasing competition in infrastructure investment coming from China as part of its sweeping Belt and Road Initiative (Sasada, Reference Samuels2019). Chinese investment has flooded into countries around the region, prompting fears about how this financial influence might be used as a tool of Chinese economic statecraft in the future, particularly vis-à-vis countries that become dependent on Chinese funding or cannot repay their debts. Japan has the strongest aid presence in Asia and frequently emphasizes the high quality and transparency of its aid projects as providing advantages to recipient countries relative to Chinese aid. Japan has also sought collaboration with the US and the European Union to provide infrastructure aid to the region.

This section has demonstrated how Japan has adapted ODA to pursue its strategic objectives over the post-World War II period. The strength of Japan's ODA program, especially in Asia, has endowed it with the potential to influence its partner states in ways that are consistent with its shifting national concerns. Over time, Japan's aims have broadened from securing market access for its companies and reintegrating into the international system to encompassing comprehensive security, human security, and traditional security objectives. In recent years, Japan has more clearly deployed this tool of economic statecraft to counter Chinese influence and expanded its ability to use ODA for a broader scope of political and security applications than previously possible.

4. Militarizing Dual-Use Outer Space Technologies

Dual-use technologies – products that can be used for both civilian and military purposes – have always existed, but over time they have become more sophisticated and more widely available (Govella, Reference Govella2019). Although they have received less attention in discussions of economic statecraft than policy measures such as sanctions, investment in and development of these technologies constitutes a type of ‘new economic statecraft’ that has implications for national and international security (Aggarwal and Reddie, Reference Aggarwal and Reddie2020). Due to their Janus-faced nature, dual-use technologies are natural tools of economic statecraft, though state actors may not necessarily be responsible for driving their creation due to the role also played by the private sector. The Japanese government is well-known for its use of industrial policy to guide the development of its economy in collaboration with Japanese companies (Johnson, Reference Johnson1982). Military technonationalism was central to Japan's industrial revolution, linking technology to the country's national security from its early days as a modern state, and its military and civilian economies have a longstanding strategic relationship (Samuels, Reference Ravenhill, Aggarwal and Govella1994). While dual-use technologies exist in a broad range of industrial sectors, this section focuses specifically on Japan's adaptive approach to technologies related to outer space because it is a domain in which US–China strategic competition has increased markedly over the past 20 years. Outer space is increasingly seen as central to states’ national security, with civilian technologies potentially having direct implications for military applications on the surface of the earth. This section demonstrates that Japan's concern about increasing competition between China and the US has led it to develop a more overtly militarized approach to its outer space dual-use technologies. Essentially, as technological advances have reshaped Japan's security needs, Japan has in turn adapted technologies as tools of economic statecraft with which to pursue its evolving strategic goals.

As in the previous two case studies, the discourse about appropriate post-World War II limitations on Japan's military activities also extended into the realm of outer space technologies. In the face of concern that rocket technologies could be used for ballistic missiles, the Diet passed a resolution in 1969 restricting Japan's space policy to ‘peaceful purposes’, requiring that its program be conducted exclusively for non-military ends and through non-military means. However, due to the close relationship between civilian and military applications of space technologies, this distinction was neither easily made nor enforced. Japan developed satellites, rockets, and other equipment, and by the mid-1980s, the country had established a mature space program (Moltz, Reference Moltz2012). Throughout this time, the civilian nature of the program was emphasized; policy was largely driven by bureaucrats and engineers (Suzuki, Reference Song and Yuan2008). During the economic downturn of the 1990s, Japanese space technology companies began to look for opportunities to expand into military applications in the face of limited commercialization prospects and shrinking budgets for civilian space projects. Companies encouraged policymakers to move in new directions with dual-use technologies and to develop the building blocks of military space infrastructure such as military communications, spy satellites, and missiles (Pekkanen and Kallender-Umezu, Reference Pekkanen2010).

In the late 1990s, security threats from North Korea began to convince Japanese policymakers that a more overtly militarized space program was in their country's national interest. North Korea's launch of a Taepodong-1 rocket over Japan in 1998 sharply accentuated the downsides to Japan's reliance on the US for reconnaissance information, so policymakers decided to advocate for a dual-use national Earth-observation capability. Due to the 1969 Diet resolution, it was officially designated as ‘multipurpose’ and civilian-operated, but the potential military application was clear, as the information gathered by this new reconnaissance satellite network could be used as a warning system against ballistic missile launches (Suzuki, Reference Song and Yuan2008). The heightened perception of threat from North Korea, combined with other setbacks experienced in Japan's space program at this time, led to the reorganization of related institutions and the creation of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) in 2001.

In the 2000s, the growing sophistication of China's outer space capabilities and the relative decline of American primacy in the domain further shifted the views of Japanese policymakers, who took steps to adapt dual-use technologies to respond to potential Chinese security threats. China's development of significant human spaceflight capabilities in 2003 kicked off a new period of competition in space, and its 2007 direct assent anti-satellite (ASAT) weapon exercise raised concerns that China could destroy Japan's satellites, threatening its security and long-term space-related goals. These concerns enabled Japan to pass a new Basic Space Law in 2008 that marked a fundamental shift from the previous legislation, allowing for ‘defensive’ functions. It linked the domain to security institutions by granting the Japan Self Defense Forces (JSDF) control of the nation's reconnaissance satellites and enhancing Japan's satellites to include high-precision satellite technology more suitable for military applications (Manriquez, Reference Manriquez2008). Outer space was also identified as an explicit priority in documents such as Japan's National Security Strategy and National Defense Program Guidelines. Beginning in 2015, Japan's Basic Space Plans framed outer space as a key part of national security planning, alluding to China's increased presence in the domain and tying elements to the US–Japan alliance (Kallender, Reference Kallender2016; National Institute for Defense Studies Japan, 2016).

Japan has adapted this tool of economic statecraft by investing in many advanced military space technologies designed to address its security concerns related to China. These have included launch systems, communications and intelligence satellites, and counterspace capabilities. These technologies enable Japan to respond to conventional threats and increase the effectiveness of its deterrence. Japan is pursuing a full-scale space situational awareness system, transitioning from a civilian-driven initiative by JAXA to a defense-driven program with Ministry of Defense and JSDF collaboration (Otani and Kohtake, Reference Oneal and Russett2019). In addition, new Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance systems and the Quasi-Zenith Satellite System are becoming increasingly connected to US systems, strengthening the ability of the US–Japan alliance to deter and respond to threats from China (Kallender and Hughes, Reference Kallender and Hughes2018).

The dual-use nature of space technologies has allowed the Japanese government to quietly funnel increasing resources from other parts of its budget into developing military-applicable technologies without attracting unwanted attention, essentially easing the exercise of economic statecraft. Kallender and Hughes (Reference Kallender and Hughes2018) point out that this budgetary strategy could effectively augment Japan's existing defense budgets by 5–10%, in ways that are not subject to Japan's self-set defense spending limit of 1% of its GDP. The Japanese government has also begun to call for more collaboration with the private sector on dual-use technologies. For example, the 2014 Strategy on Defense Production and Technical Bases released by the Ministry of Defense explicitly addressed ‘increasing borderlessness between defense technology and civilian technology’ and committed to promoting measures to utilize civilian technology (Ministry of Defense, 2014, 6). In 2015, the technology agency of the Ministry of Defense set up a National Security Technology Research Promotion Fund worth $2.7 million.

This section has shown how Japan has adapted its approach to dual-use technologies in order to counter increasing competition from China in outer space. By shifting its investment in dual-use technologies in a more militarized direction, Japan has used economic tools to pursue security goals. Japan is also trying to increase its cooperation with the US and to more fully incorporate outer space into the auspices of the US–Japan alliance. However, much of the substantive progress in this domain has been made not by public declarations by the Japanese government but by its subtle use of economic statecraft to gradually and quietly develop dual-use technologies to enhance its security in outer space as well on Earth.

5. Conclusion

By tracing the adaptation of these three different tools of Japanese economic statecraft since World War II, this article has demonstrated the ways in which economic instruments have long been important to Japan's efforts to shape its surroundings. In addition to using these tools to reintegrate into the international system in the early post-war period, Japan adapted them to address changing goals related to comprehensive security, human security, and traditional security over the decades that followed. As the rise of China led to a new environment of strategic competition with the US, Japan again adapted these economic tools in new ways to address concerns about China and to bolster the international status quo. In the arena of trade institutions, Japan has pursued arrangements that both engage and counter China in addition to supporting the regional and multilateral trade order against increasing instability triggered by the US–China trade war and mounting global populism. With respect to economic aid, Japan has responded to Chinese assertiveness by supporting initiatives that stabilize and strengthen the defense capacity of affected countries. Finally, Japan has subtly shifted its policies toward dual-use technologies to endow it with increasing ability to deal with Chinese military activity in outer space.

Examining this relatively broad range of tools enables comparison of different instruments of economic statecraft in ways that are often not possible in other studies. First, it is clear that these three economic tools operate at different levels of strategy, allowing states to adapt them for different types of objectives. Trade arrangements function at the broadest level, to shape the strategic environment and to create stable expectations in the international order. They can also help to deflect bilateral pressures and create or strengthen linkages among states whose interests or values align. As a national tool that is often bilaterally deployed, ODA helps to mold ties between two countries in a more targeted manner and enables strategic utilization of resources to support partners whose stability is tied to a state's own security interests. Development and acquisition of dual-use technology function at a more micro-level, allowing a state to use economic policy to attain specific capabilities that serve its strategic aims. These technologies may be pursued via domestic investment policy or in bilateral or multilateral partnership.

Second, these tools have differing levels of visibility that have corresponding implications for their symbolic value and risk of politicization. As the most visible tool discussed here, trade arrangements can be highly valuable as symbols of engagement and belonging in the international system, as they were to Japan in the early post-World War II period. They can also become politicized, both internationally and domestically, as exhibited by the contentious discourse around TPP as a US strategy to contain China and by the rejection of TPP by an American public increasingly frustrated with the negative effects of globalization. At the other end of the spectrum, policies around dual-use technologies are highly technocratic and often difficult for non-experts to understand, making them less likely targets for politicization, although high-profile acquisitions of technologies with potential offensive military applications can send strong signals to others states. Aid operates in a middle range where it is somewhat more visible and more susceptible to politicization but still mostly the domain of working-level bureaucrats and development professionals. Being an aid donor can be a symbol of a country's status and donations can serve as a symbol of the priority placed on specific bilateral relationships, but aid does not generally prompt intense scrutiny from domestic publics and is often less visible than high-profile trade arrangements.

The sheer diversity of tools of economic statecraft presents an opportunity for a much more comparative analysis along these lines in the future. In addition to more traditional subjects of analysis such as sanctions, there are a myriad of other economic means through which states can influence their environment. While this article has focused on trade, aid, and dual-use technology, for example, other scholars have examined financial and monetary instruments (Armijo and Katada, Reference Armijo and Katada2014). Moreover, as discussed by Aggarwal and Reddie (Reference Aggarwal and Reddiethis issue), industrial policy, sector-specific trade measures, and investment rules are also important domestic tools that are often overlooked. These tools vary in terms of the roles of states and commercial actors in their implementation, suggesting a need to more clearly understand their use in different national contexts.

This analysis also enables the identification of some trends in Japan's policy trajectory over time. The cases of trade and aid, for example, demonstrate how Japan initially used these tools to reintegrate into the international system after its defeat in World War II and later came to adapt these tools to stabilize this very system. These cases also reveal shifts in how Japan has conceptualized its security interests over time, with varying notions of comprehensive security or human security coming to the forefront during different periods. While Japan's traditional security interests have been served most prominently by the US–Japan alliance, economic tools have also been used in targeted ways to address traditional security concerns, and some domestic regulations and laws have been loosened to make this increasingly possible over time. Japan's trajectory seems to be headed in the direction of increasingly explicit linkages between economics and security, broadly defined. Domestically, this can be explained by the fact that some of the traditional fragmentation of the Japanese policymaking process has given way to reforms that have increased the power of the prime minister and centralized policy coordination that facilitates issue linkages that were more difficult in past eras of relatively stronger bureaucratic power. The combination of these domestic developments and the changing international environment has resulted in the adaptation of Japanese economic statecraft across multiple tools. This adaptive process has not been solely reactive; while Japan has used economic statecraft to respond to external events in some cases, it has tried to proactively shape international or regional conditions with economic statecraft in others.

Finally, reflecting upon the trends in Japanese economic statecraft following the rise of China and the intensification of US–China competition, this article offers some insights into middle power behavior that can be built upon by future studies. It demonstrates that Japan has used multiple tools of economic statecraft to respond to changing notions of security in specific contexts, for example. More broadly, in response to great power competition, Japan's adaptation of these three tools of economic statecraft collectively amounts to an attempt to simultaneously (1) reduce instability in the international system by bolstering the rules-based multilateral order and (2) to counter China in targeted ways as part of a broader hedging approach. First, the rules-based order offers a way to constrain great powers and stabilize international dynamics. In the face of challenges to the multilateral free trade regime from unilateralism, populism, and protectionism, Japan has sought to bolster trade arrangements. Japan's ODA to countries surrounding the South China Sea has also supported the rules-based maritime order, which is facing challenges from expanding Chinese influence and gray zone conflict. Second, Japan has used multiple forms of economic statecraft to counter perceived threats from China. In addition to the aforementioned ODA for maritime domain awareness initiatives in the South China Sea, Japan has used dual-use technologies to address concerns about Chinese activities in outer space. Trade arrangements have served as a way to simultaneously engage China and also counter it, as seen through Japan's participation in RCEP and TPP. Essentially, economic statecraft has been a way for Japan to buffer the effects of great power competition and reduce risks in an increasingly uncertain environment. In this way, the case of Japan supports the existing literature that has shown that middle powers favor multilateral institutions, rules-based order, and other diplomatic tools that allow them to mediate the vagaries of great power politics and reduce instability in the international system (e.g., Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Higgott and Nossal1993; Hatakeyama, Reference Hatakeyama2019). While middle powers may not have the ability to engage in strategic competition to the same degree and in the same manner as great powers, they have significant material and diplomatic resources at their disposal.

This article also suggests that it is important to look at the tools of economic statecraft that are not used, as well as those that are. It is notable, for example, that Japan has generally refrained from engaging in outright economic coercion or tit-for-tat retaliation in the ways that have become increasingly common with China, and more recently, the US. Instead, Japan has favored the maintenance of institutions and norms in line with the status quo multilateral trade regime and avoided actions that would further erode international trade norms. Particularly at a time of possible power transition and heightened strategic competition, middle powers may have an incentive to mediate instability and encourage compromise. If so, in aggregate, their actions can help to stabilize the international order, even in the face of volatile great power behavior.

This is not to say that all middle powers will react similarly to changes in international conditions. The term ‘middle power’ can be applied to a diverse group of states, each with its own distinct goals and capabilities. However, rather than invalidating the middle power discourse, this variation among states suggests an opportunity for further comparative studies of middle powers, emerging powers, and other states to better understand the full scope of economic statecraft strategies at play. Although middle and smaller powers are sometimes characterized as unfortunate targets of great powers’ economic statecraft initiatives, many also have the capacity to wield their own economic tools for non-economic purposes, and these links between issues require deeper inquiry. Focusing primarily on the economic statecraft of great powers omits other important forces that are shaping the international environment in ways that may mediate or exacerbate the instability of the current period of US–China tensions.

Economic statecraft is inherently controversial; some will inevitably argue that countries like Japan should do less to manipulate the linkages between economics and other issues, while others argue that they should do more (Kokubun and Glosserman, Reference Kokubun and Glosserman2018). Rather than taking a normative position on means and ends, this analysis provides a window into how a country with a range of economic tools can adapt their use to deal strategically with changes in the international environment. Increasing interdependence has expanded the available opportunities to link economics to other issues, enmeshing states in an evermore complex web of interactions with their counterparts. As states begin to turn to these tools with greater frequency, it is vital for scholars to develop a more nuanced understanding of their role in international relations.