Introduction

Psychotic experiences (PE) are attenuated forms of psychotic symptoms (e.g. delusions and hallucinations) that do not reach the clinical threshold for a psychotic disorder diagnosis. PE are known to be highly prevalent in the general population with a systematic review reporting a lifetime prevalence of 7.2% (Linscott and van Os, Reference Linscott and van Os2013) – a figure that is approximately double that of broadly defined psychotic disorders (Perälä et al., Reference Perälä, Suvisaari, Saarni, Kuoppasalmi, Isometsä, Pirkola, Partonen, Tuulio-Henriksson, Hintikka, Kieseppä, Härkänen, Koskinen and Lönnqvist2007). It has been reported that PE are transitory in about 80% of the cases, while approximately 7% eventually develop a psychotic disorder (van Os and Reininghaus, Reference van Os and Reininghaus2016).

One of the most consistently reported risk factors for schizophrenia is cognitive decrement in youth (Aylward et al., Reference Aylward, Walker and Bettes1984), consistent with neurodevelopmental theories of schizophrenia aetiology (Fatemi and Folsom, Reference Fatemi and Folsom2009). Despite the evidence suggesting that objective deficits in cognition (e.g. assessed using standardised neuropsychological testing) are also often evident in the at-risk mental state (Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Deste, Smieskova, Barlati, Yung, Howes, Stieglitz, Vita, McGuire and Borgwardt2012) or PE (Mollon et al., Reference Mollon, David, Morgan, Frissa, Glahn, Pilecka, Hatch, Hotopf and Reichenberg2016), little is known about the important concept of subjective cognitive complaints (SCC) in people with PE. SCC are everyday memory and related cognitive concerns expressed by people who may or may not have deficits on objective testing, and are common in all age groups (Begum et al., Reference Begum, Dewey, Hassiotis, Prince, Wessely and Stewart2014). SCC are critical in identifying subtle changes in everyday functioning that are often a precursor for more serious cognitive decline and functioning, which may not otherwise be detected (Hohman et al., Reference Hohman, Beason-Held, Lamar and Resnick2011). Studying the association between SCC and PE is important as the subjective nature of SCC makes it a much more likely candidate for rapid clinical assessment of individuals who may be at risk for psychosis, given that SCC can be self-reported and does not require burdensome neuropsychological testing and specially trained staff. Furthermore, the prevalence of objective cognitive deficits usually increases with age and is most common at older ages when psychosis onset is not common. However, in the case of SCC, previous studies have shown that the prevalence of SCC may be quite similar in younger and older people (Begum et al., Reference Begum, Dewey, Hassiotis, Prince, Wessely and Stewart2014). This may be because cognitive decline can be very concerning to the individual at younger ages, whereas at older ages, this may be considered normal. Thus, it is possible that SCC may be a particularly useful marker for psychosis risk among younger people who are at higher risk for psychosis.

Furthermore, another notable gap in the literature is the scarcity of data on cognition and PE from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) as previous studies on this topic, which have used objective measures of cognitive function, are all from high-income countries. This is an important omission as the effect of cognition on psychosis is likely influenced by environmental and genetic factors that may differ between countries with different ethnic compositions or levels of socioeconomic development. In addition, cognitive decrements in individuals in LMICs may be more likely to reflect early static injury than trajectories of postnatal development as factors such as foetal hypoxia, maternal infection and obstetric complications (Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, McDougall, Xu, Croudace, Richards and Jones2012) may be more common in LMICs (James et al., Reference James, Abate, Abate, Abay, Abbafati, Abbasi, Abbastabar, Abd-Allah, Abdela, Abdelalim, Abdollahpour, Abdulkader, Abebe, Abera, Abil, Abraha, Abu-Raddad, Abu-Rmeileh, Accrombessi, Acharya, Acharya, Ackerman, Adamu, Adebayo, Adekanmbi, Adetokunboh, Adib, Adsuar, Afanvi, Afarideh, Afshin, Agarwal, Agesa, Aggarwal, Aghayan, Agrawal, Ahmadi, Ahmadi, Ahmadieh, Ahmed, Aichour, Aichour, Aichour, Akinyemiju, Akseer, Al-Aly, Al-Eyadhy, Al-Mekhlafi, Al-Raddadi, Alahdab, Alam, Alam, Alashi, Alavian, Alene, Alijanzadeh, Alizadeh-Navaei, Aljunid, Alkerwi, Alla, Allebeck, Alouani, Altirkawi, Alvis-Guzman, Amare, Aminde, Ammar, Amoako, Anber, Andrei, Androudi, Animut, Anjomshoa, Ansha, Antonio, Anwari, Arabloo, Arauz, Aremu, Ariani, Armoon, Ärnlöv, Arora, Artaman, Aryal, Asayesh, Asghar, Ataro, Atre, Ausloos, Avila-Burgos, Avokpaho, Awasthi, Ayala Quintanilla, Ayer, Azzopardi, Babazadeh, Badali, Badawi, Bali, Ballesteros, Ballew, Banach, Banoub, Banstola, Barac, Barboza, Barker-Collo, Bärnighausen, Barrero, Baune, Bazargan-Hejazi, Bedi, Beghi, Behzadifar, Behzadifar, Béjot, Belachew, Belay, Bell, Bello, Bensenor, Bernabe, Bernstein, Beuran, Beyranvand, Bhala, Bhattarai, Bhaumik, Bhutta, Biadgo, Bijani, Bikbov, Bilano, Bililign, Bin Sayeed, Bisanzio, Blacker, Blyth, Bou-Orm, Boufous, Bourne, Brady, Brainin, Brant, Brazinova, Breitborde, Brenner, Briant, Briggs, Briko, Britton, Brugha, Buchbinder, Busse, Butt, Cahuana-Hurtado, Cano, Cárdenas, Carrero, Carter, Carvalho, Castañeda-Orjuela, Castillo Rivas, Castro, Catalá-López, Cercy, Cerin, Chaiah, Chang, Chang, Chang, Charlson, Chattopadhyay, Chattu, Chaturvedi, Chiang, Chin, Chitheer, Choi, Chowdhury, Christensen, Christopher, Cicuttini, Ciobanu, Cirillo, Claro, Collado-Mateo, Cooper, Coresh, Cortesi, Cortinovis, Costa, Cousin, Criqui, Cromwell, Cross, Crump, Dadi, Dandona, Dandona, Dargan, Daryani, Das Gupta, Das Neves, Dasa, Davey, Davis, Davitoiu, De Courten, De La Hoz, De Leo, De Neve, Degefa, Degenhardt, Deiparine, Dellavalle, Demoz, Deribe, Dervenis, Des Jarlais, Dessie, Dey, Dharmaratne, Dinberu, Dirac, Djalalinia, Doan, Dokova, Doku, Dorsey, Doyle, Driscoll, Dubey, Dubljanin, Duken, Duncan, Duraes, Ebrahimi, Ebrahimpour, Echko, Edvardsson, Effiong, Ehrlich, El Bcheraoui, El Sayed Zaki, El-Khatib, Elkout, Elyazar, Enayati, Endries, Er, Erskine, Eshrati, Eskandarieh, Esteghamati, Esteghamati, Fakhim, Fallah Omrani, Faramarzi, Fareed, Farhadi, Farid, Farinha, Farioli, Faro, Farvid, Farzadfar, Feigin, Fentahun, Fereshtehnejad, Fernandes, Fernandes, Ferrari, Feyissa, Filip, Fischer, Fitzmaurice, Foigt, Foreman, Fox, Frank, Fukumoto, Fullman, Fürst, Furtado, Futran, Gall, Ganji, Gankpe, Garcia-Basteiro, Gardner, Gebre, Gebremedhin, Gebremichael, Gelano, Geleijnse, Genova-Maleras, Geramo, Gething, Gezae, Ghadiri, Ghasemi Falavarjani, Ghasemi-Kasman, Ghimire, Ghosh, Ghoshal, Giampaoli, Gill, Gill, Ginawi, Giussani, Gnedovskaya, Goldberg, Goli, Gómez-Dantés, Gona, Gopalani, Gorman, Goulart, Goulart, Grada, Grams, Grosso, Gugnani, Guo, Gupta, Gupta, Gupta, Gupta, Gyawali, Haagsma, Hachinski, Hafezi-Nejad, Haghparast Bidgoli, Hagos, Hailu, Haj-Mirzaian, Haj-Mirzaian, Hamadeh, Hamidi, Handal, Hankey, Hao, Harb, Harikrishnan, Haro, Hasan, Hassankhani, Hassen, Havmoeller, Hawley, Hay, Hay, Hedayatizadeh-Omran, Heibati, Hendrie, Henok, Herteliu, Heydarpour, Hibstu, Hoang, Hoek, Hoffman, Hole, Homaie Rad, Hoogar, Hosgood, Hosseini, Hosseinzadeh, Hostiuc, Hostiuc, Hotez, Hoy, Hsairi, Htet, Hu, Huang, Huynh, Iburg, Ikeda, Ileanu, Ilesanmi, Iqbal, Irvani, Irvine, Islam, Islami, Jacobsen, Jahangiry, Jahanmehr, Jain, Jakovljevic, Javanbakht, Jayatilleke, Jeemon, Jha, Jha, Ji, Johnson, Jonas, Jozwiak, Jungari, Jürisson, Kabir, Kadel, Kahsay, Kalani, Kanchan, Karami, Karami Matin, Karch, Karema, Karimi, Karimi, Kasaeian, Kassa, Kassa, Kassa, Kassebaum, Katikireddi, Kawakami, Karyani, Keighobadi, Keiyoro, Kemmer, Kemp, Kengne, Keren, Khader, Khafaei, Khafaie, Khajavi, Khalil, Khan, Khan, Khan, Khang, Khazaei, Khoja, Khosravi, Khosravi, Kiadaliri, Kiirithio, Kim, Kim, Kim, Kim, Kim, Kimokoti, Kinfu, Kisa, Kissimova-Skarbek, Kivimäki, Knudsen, Kocarnik, Kochhar, Kokubo, Kolola, Kopec, Kosen, Kotsakis, Koul, Koyanagi, Kravchenko, Krishan, Krohn, Kuate Defo, Kucuk Bicer, Kumar, Kumar, Kyu, Lad, Lad, Lafranconi, Lalloo, Lallukka, Lami, Lansingh, Latifi, Lau, Lazarus, Leasher, Ledesma, Lee, Leigh, Leung, Levi, Lewycka, Li, Li, Liao, Liben, Lim, Lim, Liu, Lodha, Looker, Lopez, Lorkowski, Lotufo, Low, Lozano, Lucas, Lucchesi, Lunevicius, Lyons, Ma, Macarayan, Mackay, Madotto, Magdy Abd El Razek, Magdy Abd El Razek, Maghavani, Mahotra, Mai, Majdan, Majdzadeh, Majeed, Malekzadeh, Malta, Mamun, Manda, Manguerra, Manhertz, Mansournia, Mantovani, Mapoma, Maravilla, Marcenes, Marks, Martins-Melo, Martopullo, März, Marzan, Mashamba-Thompson, Massenburg, Mathur, Matsushita, Maulik, Mazidi, McAlinden, McGrath, McKee, Mehndiratta, Mehrotra, Mehta, Mehta, Mejia-Rodriguez, Mekonen, Melese, Melku, Meltzer, Memiah, Memish, Mendoza, Mengistu, Mengistu, Mensah, Mereta, Meretoja, Meretoja, Mestrovic, Mezerji, Miazgowski, Miazgowski, Millear, Miller, Miltz, Mini, Mirarefin, Mirrakhimov, Misganaw, Mitchell, Mitiku, Moazen, Mohajer, Mohammad, Mohammadifard, Mohammadnia-Afrouzi, Mohammed, Mohammed, Mohebi, Moitra, Mokdad, Molokhia, Monasta, Moodley, Moosazadeh, Moradi, Moradi-Lakeh, Moradinazar, Moraga, Morawska, Moreno Velásquez, Morgado-Da-Costa, Morrison, Moschos, Mousavi, Mruts, Muche, Muchie, Mueller, Muhammed, Mukhopadhyay, Muller, Mumford, Murhekar, Musa, Musa, Mustafa, Nabhan, Nagata, Naghavi, Naheed, Nahvijou, Naik, Naik, Najafi, Naldi, Nam, Nangia, Nansseu, Nascimento, Natarajan, Neamati, Negoi, Negoi, Neupane, Newton, Ngunjiri, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nichols, Ningrum, Nixon, Nolutshungu, Nomura, Norheim, Noroozi, Norrving, Noubiap, Nouri, Nourollahpour Shiadeh, Nowroozi, Nsoesie, Nyasulu, Odell, Ofori-Asenso, Ogbo, Oh, Oladimeji, Olagunju, Olagunju, Olivares, Olsen, Olusanya, Ong, Ong, Oren, Ortiz, Ota, Otstavnov, Øverland, Owolabi, Mahesh, Pacella, Pakpour, Pana, Panda-Jonas, Parisi, Park, Parry, Patel, Pati, Patil, Patle, Patton, Paturi, Paulson, Pearce, Pereira, Perico, Pesudovs, Pham, Phillips, Pigott, Pillay, Piradov, Pirsaheb, Pishgar, Plana-Ripoll, Plass, Polinder, Popova, Postma, Pourshams, Poustchi, Prabhakaran, Prakash, Prakash, Purcell, Purwar, Qorbani, Quistberg, Radfar, Rafay, Rafiei, Rahim, Rahimi, Rahimi-Movaghar, Rahimi-Movaghar, Rahman, Rahman, Rahman, Rahman, Rai, Rajati, Ram, Ranjan, Ranta, Rao, Rawaf, Rawaf, Reddy, Reiner, Reinig, Reitsma, Remuzzi, Renzaho, Resnikoff, Rezaei, Rezai, Ribeiro, Robinson, Roever, Ronfani, Roshandel, Rostami, Roth, Roy, Rubagotti, Sachdev, Sadat, Saddik, Sadeghi, Saeedi Moghaddam, Safari, Safari, Safari-Faramani, Safdarian, Safi, Safiri, Sagar, Sahebkar, Sahraian, Sajadi, Salam, Salama, Salamati, Saleem, Saleem, Salimi, Salomon, Salvi, Salz, Samy, Sanabria, Sang, Santomauro, Santos, Santos, Santric Milicevic, Sao Jose, Sardana, Sarker, Sarrafzadegan, Sartorius, Sarvi, Sathian, Satpathy, Sawant, Sawhney, Saxena, Saylan, Schaeffner, Schmidt, Schneider, Schöttker, Schwebel, Schwendicke, Scott, Sekerija, Sepanlou, Serván-Mori, Seyedmousavi, Shabaninejad, Shafieesabet, Shahbazi, Shaheen, Shaikh, Shams-Beyranvand, Shamsi, Shamsizadeh, Sharafi, Sharafi, Sharif, Sharif-Alhoseini, Sharma, Sharma, She, Sheikh, Shi, Shibuya, Shigematsu, Shiri, Shirkoohi, Shishani, Shiue, Shokraneh, Shoman, Shrime, Si, Siabani, Siddiqi, Sigfusdottir, Sigurvinsdottir, Silva, Silveira, Singam, Singh, Singh, Singh, Sinha, Skiadaresi, Slepak, Sliwa, Smith, Smith, Soares Filho, Sobaih, Sobhani, Sobngwi, Soneji, Soofi, Soosaraei, Sorensen, Soriano, Soyiri, Sposato, Sreeramareddy, Srinivasan, Stanaway, Stein, Steiner, Steiner, Stokes, Stovner, Subart, Sudaryanto, Sufiyan, Sunguya, Sur, Sutradhar, Sykes, Sylte, Tabarés-Seisdedos, Tadakamadla, Tadesse, Tandon, Tassew, Tavakkoli, Taveira, Taylor, Tehrani-Banihashemi, Tekalign, Tekelemedhin, Tekle, Temesgen, Temsah, Temsah, Terkawi, Teweldemedhin, Thankappan, Thomas, Tilahun, To, Tonelli, Topor-Madry, Topouzis, Torre, Tortajada-Girbés, Touvier, Tovani-Palone, Towbin, Tran, Tran, Troeger, Truelsen, Tsilimbaris, Tsoi, Tudor Car, Tuzcu, Ukwaja, Ullah, Undurraga, Unutzer, Updike, Usman, Uthman, Vaduganathan, Vaezi, Valdez, Varughese, Vasankari, Venketasubramanian, Villafaina, Violante, Vladimirov, Vlassov, Vollset, Vosoughi, Vujcic, Wagnew, Waheed, Waller, Wang, Wang, Weiderpass, Weintraub, Weiss, Weldegebreal, Weldegwergs, Werdecker, West, Whiteford, Widecka, Wijeratne, Wilner, Wilson, Winkler, Wiyeh, Wiysonge, Wolfe, Woolf, Wu, Wu, Wyper, Xavier, Xu, Yadgir, Yadollahpour, Yahyazadeh Jabbari, Yamada, Yan, Yano, Yaseri, Yasin, Yeshaneh, Yimer, Yip, Yisma, Yonemoto, Yoon, Yotebieng, Younis, Yousefifard, Yu, Zadnik, Zaidi, Zaman, Zamani, Zare, Zeleke, Zenebe, Zhang, Zhao, Zhou, Zodpey, Zucker, Vos and Murray2018).

Given the lack of studies specifically on SCC and PE, and the scarcity of data on PE and cognitive function in adulthood, especially from LMICs, we analysed predominantly nationally representative community-based data on 224 842 individuals aged ⩾18 years from 48 LMICs, who participated in the World Health Survey (WHS) to (a) examine the association between SCC and PE by age groups; and (b) to assess the extent to which various factors explain the SCC–PE association.

Methods

The survey

The WHS was a cross-sectional, community-based study undertaken in 2002–2004 in 70 countries worldwide. Details of the survey are provided in the WHO website (http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/en/). Briefly, data were collected using stratified multi-stage random cluster sampling. Individuals aged ⩾18 years with a valid home address were eligible to participate. Each member of the household had an equal probability of being selected by utilising Kish tables. A standardised questionnaire, translated accordingly, was used across all countries. The individual response rate across all countries was 98.5% (Nuevo et al., Reference Nuevo, Chatterji, Verdes, Naidoo, Arango and Ayuso-Mateos2012). Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the ethical boards at each study site. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Sampling weights were generated to adjust for non-response and the population distribution reported by the United Nations Statistical Division.

Data were publicly available for 69 countries. Of these, ten countries were excluded due to a lack of sampling information. Furthermore, ten high-income countries were excluded in order to focus on LMICs. Moreover, Turkey was deleted due to lack of data on PE. Thus, the final sample consisted of 48 LMICs (n = 242 952) according to the World Bank classification at the time of the survey (2003). The data were nationally representative for all countries with the exception of China, Comoros, the Republic of Congo, Ivory Coast, India and Russia. The included countries and their sample sizes are provided in eTable 1 in the Supplementary material.

Subjective cognitive complaints

SCC were assessed with two questions: (a) Overall in the last 30 days, how much difficulty did you have with concentrating or remembering things?; and (b) In the last 30 days, how much difficulty did you have in learning a new task (e.g. learning how to get to a new place, learning a new game, learning a new recipe, etc.)? (Ghose and Abdoul Razak, Reference Ghose and Abdoul Razak2017). Each item was scored on a five-point scale: none (code = 1), mild (code = 2), moderate (code = 3), severe (code = 4) and extreme/cannot do (code = 5). Since these answer options were an ordered categorical scale, as in previous WHS studies, we conducted factor analysis with polychoric correlations to incorporate the covariance structure of the answers provided for individual questions measuring a similar construct (Moussavi et al., Reference Moussavi, Chatterji, Verdes, Tandon, Patel and Ustun2007; Nuevo et al., Reference Nuevo, Van Os, Arango, Chatterji and Ayuso-Mateos2013; Stubbs et al., Reference Stubbs, Koyanagi, Thompson, Veronese, Carvalho, Solomi, Mugisha, Schofield, Cosco, Wilson and Vancampfort2016; Koyanagi et al., Reference Koyanagi, Vancampfort, Carvalho, DeVylder, Haro, Pizzol, Veronese and Stubbs2017). The principal component method was used for factor extraction, while factor scores were obtained using the regression scoring method. These factor scores were later converted to scores ranging from 0 to 10 to create a SCC scale with higher values representing more severe cognitive complaints. In order to assess whether there are any differences in the association between the two different types of SCC and PE, we also dichotomised these variables as severe/extreme (codes 4 and 5) or else.

Psychotic experiences

Participants were asked questions on positive psychotic symptoms (delusional mood, delusions of reference and persecution, delusions of control, hallucinations) which came from the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) 3.0 (Kessler and Ustun, Reference Kessler and Ustun2004) (specific questions can be found in eTable 2). This psychosis module has been reported to be highly consistent with clinician ratings (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Peters and Andrews1998). Individuals who endorsed at least one of the four psychotic symptoms were considered to have PE.

Influential factors

We assessed the influence of current smoking, heavy drinking, chronic physical conditions, sleep problems, depression, anxiety, perceived stress and antipsychotic use in the association between SCC and PE for their previously reported association between both cognitive impairment and PE (Tschanz et al., Reference Tschanz, Pfister, Wanzek, Corcoran, Smith, Tschanz, Steffens, Ostbye, Welsh-Bohmer and Norton2013; Begum et al., Reference Begum, Dewey, Hassiotis, Prince, Wessely and Stewart2014; Spira et al., Reference Spira, Chen-Edinboro, Wu and Yaffe2014; Koyanagi and Stickley, Reference Koyanagi and Stickley2015; DeVylder et al., Reference DeVylder, Koyanagi, Unick, Oh, Nam and Stickley2016; Lara et al., Reference Lara, Koyanagi, Olaya, Lobo, Miret, Tyrovolas, Ayuso-Mateos and Haro2016; Lara et al., Reference Lara, Koyanagi, Domenech-Abella, Miret, Ayuso-Mateos and Haro2017; Ballesteros et al., Reference Ballesteros, Sanchez-Torres, Lopez-Ilundain, Cabrera, Lobo, Gonzalez-Pinto, Diaz-Caneja, Corripio, Vieta, de la Serna, Bobes, Usall, Contreras, Lorente-Omenaca, Mezquida, Bernardo and Cuesta2018; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Saha, Lim, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Benjet, Bromet, Bruffaerts, Caldas-de-Almeida, de Girolamo, de Jonge, Degenhardt, Florescu, Gureje, Haro, Hu, Karam, Kovess-Masfety, Lee, Lepine, Mneimneh, Navarro-Mateu, Piazza, Posada-Villa, Sampson, Stagnaro, Kessler and McGrath2018). Heavy episodic drinking was defined as having consumed ⩾4 (female) or ⩾5 (male) standard alcoholic beverages on ⩾2 days in the past 7 days (Vancampfort et al., Reference Vancampfort, Stubbs, Hallgren and Koyanagi2017). Chronic physical conditions referred to having at least one of arthritis, angina, asthma, diabetes, visual impairment or hearing problems (details on these variables are provided in eTable 3). Sleep problems were operationalised as severe/extreme problems with sleeping, such as falling asleep, waking up frequently during the night or waking up too early in the morning in the past 30 days (Koyanagi and Stickley, Reference Koyanagi and Stickley2015). Depression referred to having had a lifetime diagnosis of depression or having had past 12 months depression assessed by questions from the World Mental Health Survey version of the CIDI (Kessler and Ustun, Reference Kessler and Ustun2004). Anxiety was defined as severe/extreme problems of worry or anxiety in the past 30 days (Koyanagi and Stickley, Reference Koyanagi and Stickley2015). Past 30-day perceived stress was assessed with two questions from the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Kamarck and Mermelstein1983). The scale in our study ranged from 2 to 10 with higher scores representing higher levels of stress (DeVylder et al., Reference DeVylder, Koyanagi, Unick, Oh, Nam and Stickley2016). Antipsychotic use was confirmed by the interviewer who checked the drugs used by the participant in the past 2 weeks.

Control variables

Control variables included those on sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, wealth, years of education received). Country-wise wealth quintiles were created using principal component analysis based on 15–20 assets depending on the country. We did not assess the influence of these factors in the PE–SCC relationship as these sociodemographic characteristics are often considered to be non-modifiable.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with Stata 14.1 (Stata Corp LP, College station, Texas, USA). The difference in sample characteristics was tested by χ 2 test and Student's t-tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the association between SCC (exposure) and PE (outcome). Two models were constructed: model 1 – adjusted for sociodemographics (age, sex, wealth, education and country); and model 2 – adjusted for factors in model 1 and smoking, heavy drinking, chronic physical condition, sleep problems, depression, anxiety, perceived stress and antipsychotic use. In order to assess whether the association between SCC and PE is different by age groups and sex, we conducted interaction analysis by including the product term [age group (18–44, 45–64, ⩾65 years) × SCC] or (sex × SCC) in the fully adjusted model using the overall sample. The results showed that there was no significant interaction by sex but that age is a significant effect modifier. Thus, we also conducted analyses stratifying by age groups. We also repeated this analysis by using the two different types of SCC as the exposure variable.

Next, to gain an understanding on the extent to which various factors may explain the relation between SCC and PE, we conducted mediation analysis using the overall sample. Specifically, we focused on smoking, heavy drinking, chronic physical conditions, sleep problems, depression, anxiety, perceived stress and antipsychotic use. We used the khb (Karlson Holm Breen) command in Stata (Breen et al., Reference Breen, Karlson and Holm2013) for this purpose. This method can be applied in logistic regression models and decomposes the total effect of a variable into direct and indirect effects (i.e. the mediational effect). Using this method, the percentage of the main association explained by the mediator can also be calculated (mediated percentage). Each potential influential factor was included in the model individually apart from an analysis where all mental health factors were included simultaneously in the model. The mediation analyses were adjusted for age, sex, education, wealth and country. Finally, in order to assess whether the association between SCC and PE is consistent across countries, country-wise analyses adjusting for age, sex, education and wealth were also conducted.

As in previous WHS studies, adjustment for country was done using fixed-effects models by including dummy variables for each country (Koyanagi and Stickley, Reference Koyanagi and Stickley2015; DeVylder et al., Reference DeVylder, Koyanagi, Unick, Oh, Nam and Stickley2016). All variables were included in the regression analysis as categorical variables with the exception of age, education, perceived stress and the SCC scale (continuous variables). All analyses excluded individuals with a self-reported lifetime diagnosis of psychosis (n = 2424) as PE by definition do not include conditions that reach the clinical threshold for a diagnosis. Some countries were not included in the analyses including perceived stress (Brazil, Hungary, Zimbabwe) and anxiety (Morocco) as data were not collected in these countries. Taylor linearisation methods were used in all analyses to account for the sample weighting and complex study design. Results from the logistic regression analyses are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-sided).

Results

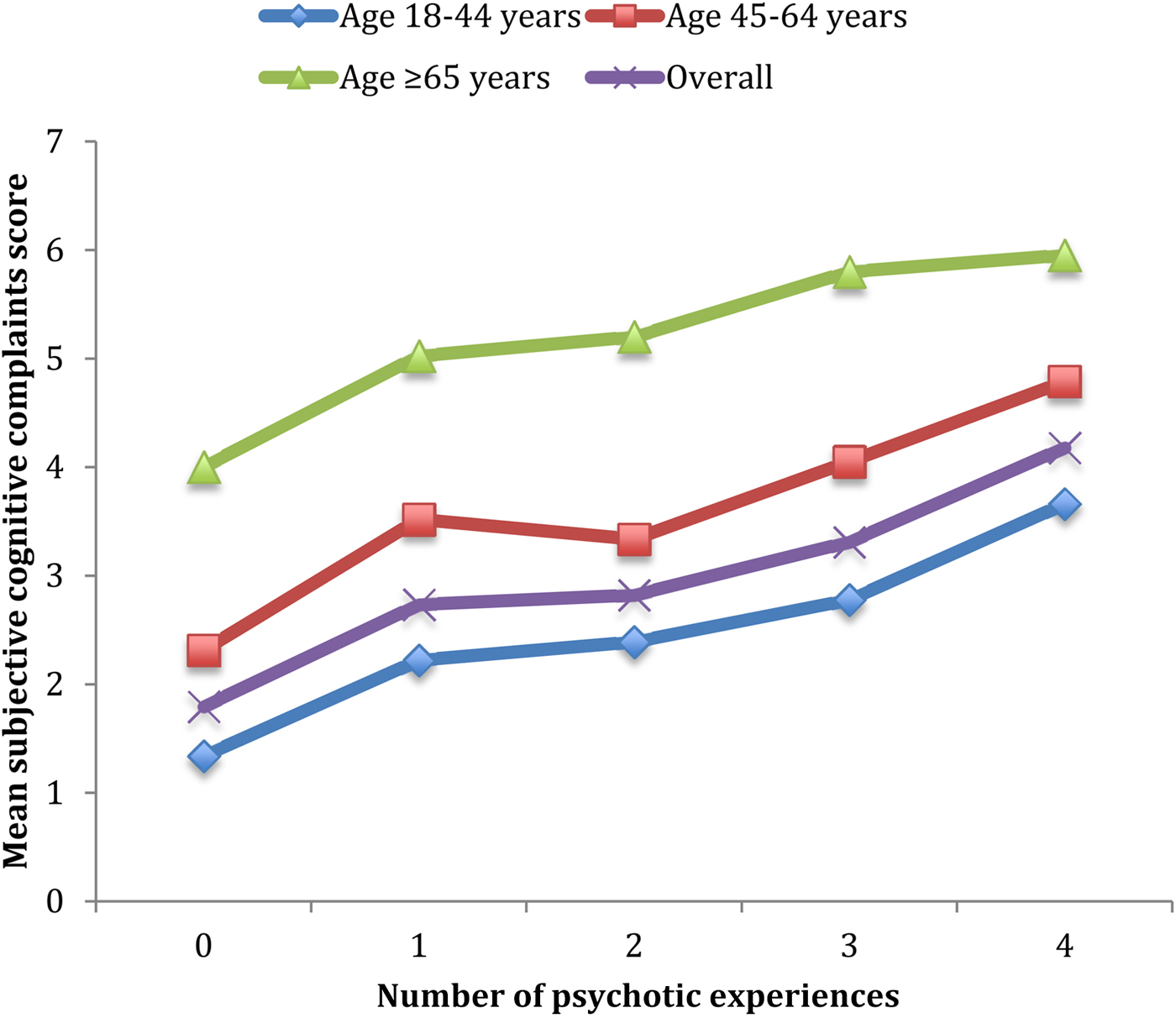

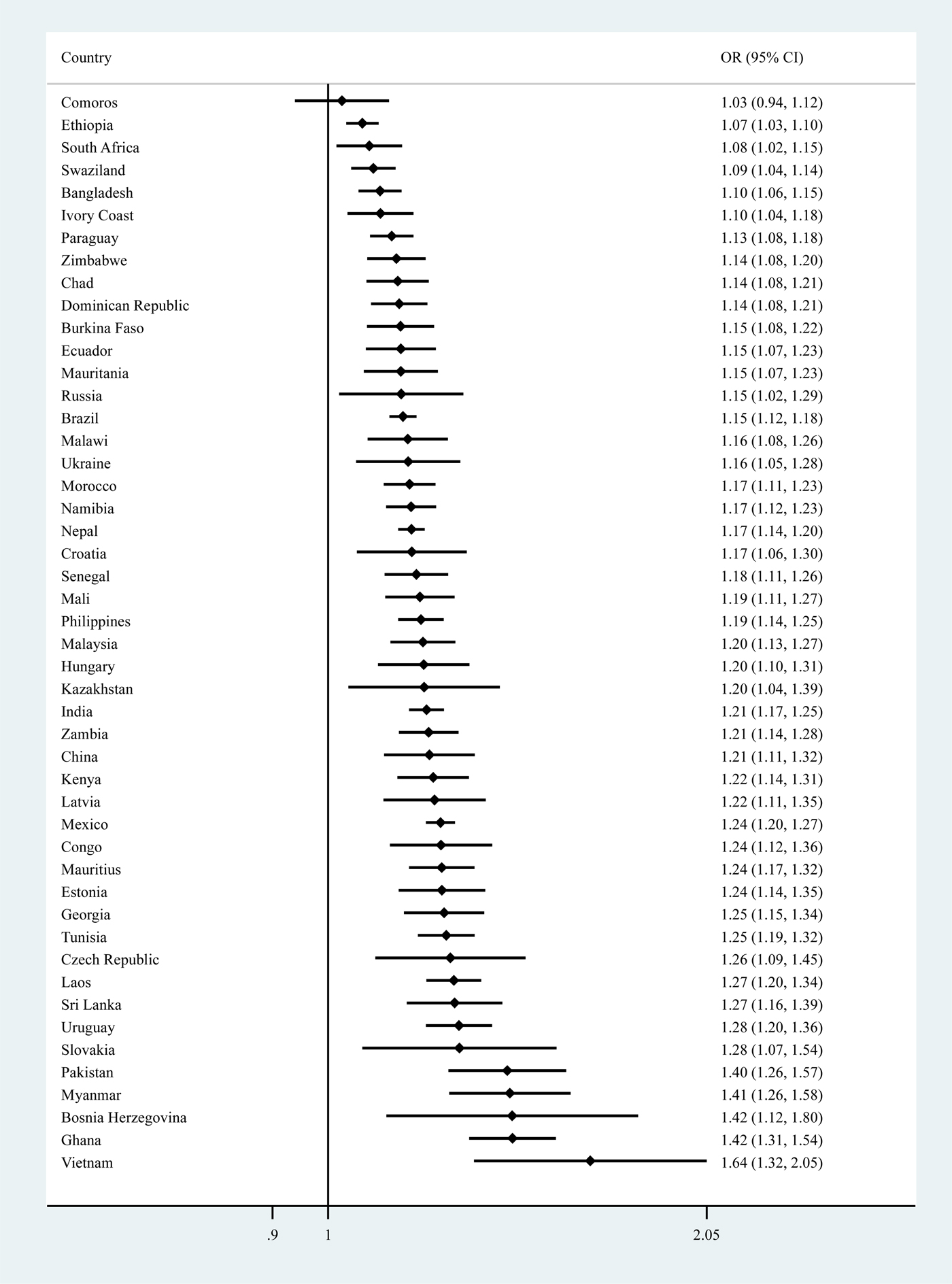

The final sample consisted of 224 842 people without a psychotic disorder. The overall prevalence of PE was 13.8%. The sample characteristics are provided in Table 1. The mean (SD) age was 38.3 (16.0) and 49.3% were males. There was a near-linear association between increasing numbers of different types of PE and mean SCC scores for the overall sample and all age groups (Fig. 1). In the overall model adjusted for sociodemographics, a one-unit increase in the SCC scale ranging from 0 to 10 was associated with a 1.17 (95% CI 1.16–1.18) times higher odds for PE (model 1) (Table 2). After further adjustment for other factors, the OR was attenuated to 1.08 (95% CI 1.06–1.10) but remained significant (model 2). Similar associations were observed in age-stratified analyses but the association was strongest in the youngest age group. Interaction analysis showed that compared with those aged 18–44 years, the association was significantly weaker among those aged 45–64 years (interaction term P = 0.003) while the interaction term for age ⩾65 years did not reach significance (interaction term P = 0.080) possibly due to lack of statistical power for the small number of individuals aged ⩾65 years (8.5%). The association between PE and the two different types of SCC, when examined individually rather than as a composite score, were similar (eTable 4). The largest proportion of the association between SCC and PE was explained by perceived stress (17.6%), followed by depression (17.4%), anxiety (16.5%), sleep problems (12.3%) and chronic physical conditions (11.8%) (Table 3). When mental health factors (perceived stress, depression, anxiety, sleep problems) were entered simultaneously into the model, they collectively explained 43.4% of the association (data only shown in text). Greater severity of SCC was significantly associated with PE in 47 of the 48 countries included in the study (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Mean subjective cognitive complaints score by number of different types of psychotic experiences. The variable on subjective cognitive complaints was a scale ranging from 0 to 10 with higher scores representing greater severity of subjective cognitive complaints. The four types of psychotic experiences assessed were: delusional mood, delusions of reference and persecution, and delusions of control, hallucinations

Fig. 2. County-wise association between subjective cognitive complaints and psychotic experiences (outcome) estimated by multivariable logistic regression. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. Models are adjusted for age, sex, wealth and education. The variable on subjective cognitive complaints was a scale ranging from 0 to 10 with higher scores representing greater severity of subjective cognitive complaints.

Table 1. Sample characteristic (overall and by presence of psychotic experiences)

Data are % or mean (standard deviation).

a P-value was calculated by χ 2 tests and Student's t-tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

b The variable on perceived stress was a scale ranging from 2 to 10 with higher scores representing higher levels of perceived stress.

Table 2. Association between subjective cognitive complaints and psychotic experiences (outcome) estimated by multivariable logistic regression

Data are odds ratio (95% confidence interval).

Models are adjusted for all variables in the respective column and country.

a Morocco, Brazil, Hungary and Zimbabwe are not included due to lack of data on perceived stress or anxiety.

b The variable on subjective cognitive complaints was a scale ranging from 0 to 10 with higher scores representing greater severity of subjective cognitive complaints.

c The variable on perceived stress was a scale ranging from 2 to 10 with higher scores representing higher levels of perceived stress.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Table 3. Mediating effects of potentially influential factors in the association between subjective cognitive complaints and psychotic experiences

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Models are adjusted for age, sex, education, wealth and country.

The variable on subjective cognitive complaints was a scale ranging from 0 to 10 with higher scores representing greater severity of subjective cognitive complaints.

a % Mediated was only calculated in the presence of a significant indirect effect.

b Morocco was not included due to lack of data.

c Brazil, Hungary and Zimbabwe were not included due to lack of data.

Discussion

In our study, we found that greater impairments in subjective cognitive ability were associated with higher odds for PE in adults across the life span and that this association was particularly pronounced in the youngest age group. Perceived stress, depression, anxiety, sleep problems and chronic physical conditions explained 11.8–17.6% of the SCC–PE association (with mental health factors collectively explaining 43.4%) but this association remained significant even after full adjustment. SCC were significantly associated with higher odds for PE in 47 of the 48 countries studied. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first that specifically focuses on SCC and PE. SCC can identify cognitive changes that affect individuals on a day-to-day basis in contrast to objective cognitive measures, which often do not reflect tasks required for everyday functioning. Importantly, subjective cognitive impairments can be very easily screened in clinical practice by asking patients to self-report recent cognitive difficulties. This stands in contrast to objective neuropsychological measures of cognition, which may be difficult to implement broadly across practice settings (particularly those in which resources or time with patients is limited). Furthermore, subjective cognitive-perceptive basic symptoms have been shown to have high predictive power in identifying subjects at high risk for developing psychosis (Schultze-Lutter et al., Reference Schultze-Lutter, Ruhrmann, Fusar-Poli, Bechdolf, Schimmelmann and Klosterkotter2012).

Regarding the age-related trends in the association between cognitive function and PE, this has only been assessed in one study (Mollon et al., Reference Mollon, David, Morgan, Frissa, Glahn, Pilecka, Hatch, Hotopf and Reichenberg2016). This UK study found that medium-to-large impairments in neuropsychological functioning (i.e. IQ, verbal knowledge, working memory, memory) was only observed in the older age group (i.e. ⩾50 years). In contrast, our study found that SCC were more strongly associated with PE in the younger age group. The difference in results may be related to different measures of cognitive function used or with different settings. However, this may also be related with different causes for SCC in the younger and older age groups. For example, one study showed that stress and multi-tasking were frequently reported as the causes of memory complaints among middle-aged adults, while age/ageing was the common cause in older adults (Vestergren and Nilsson, Reference Vestergren and Nilsson2011). Thus, it is also possible that SCC are more indicative of mental problems which are not associated with age-related changes in cognition in the younger age group. Our finding that SCC was most strongly associated with PE among young adults who are at highest risk for psychosis supports the potential value of SCC as an indicator for psychosis risk.

The fact that mental health problems explained the largest proportion (collectively 43.4%) of the SCC–PE association may not be surprising given that about two-thirds of PE occur in conjunction with a diagnosable non-psychotic mental disorder, with PE often being a marker of severe affective disorders (Wigman et al., Reference Wigman, van Nierop, Vollebergh, Lieb, Beesdo-Baum, Wittchen and van Os2012; van Os, Reference van Os2014). Common mental disorders such as depression may also hasten cognitive decline via hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation and chronic inflammation, which may lead to hippocampal atrophy and frontostriatal abnormalities (Alexopoulos, Reference Alexopoulos2003; Rapp et al., Reference Rapp, Schnaider-Beeri, Grossman, Sano, Perl, Purohit, Gorman and Haroutunian2006; Hermida et al., Reference Hermida, McDonald, Steenland and Levey2012; Diniz et al., Reference Diniz, Sibille, Ding, Tseng, Aizenstein, Lotrich, Becker, Lopez, Lotze, Klunk, Reynolds and Butters2014). In the case of perceived stress, which explained the largest proportion of the association, prolonged elevation of cortisol (HPA axis response to chronic stress) may result in both cognitive decline (Greenberg et al., Reference Greenberg, Tanev, Marin and Pitman2014) and PE (Muck-Seler et al., Reference Muck-Seler, Pivac, Jakovljevic and Brzovic1999). Alternatively, it is also possible that perceived stress due to or complicated by cognitive decline may lead to the emergence of PE (DeVylder et al., Reference DeVylder, Koyanagi, Unick, Oh, Nam and Stickley2016).

Chronic physical conditions also explained 11.8% of the association. A bidirectional association between chronic physical conditions and PE may exist, although temporally primary PE seem to be more common, and this association may be explained by a complex interplay of factors such as pain, sleep problems and psychological distress (Scott et al., Reference Scott, Saha, Lim, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Benjet, Bromet, Bruffaerts, Caldas-de-Almeida, de Girolamo, de Jonge, Degenhardt, Florescu, Gureje, Haro, Hu, Karam, Kovess-Masfety, Lee, Lepine, Mneimneh, Navarro-Mateu, Piazza, Posada-Villa, Sampson, Stagnaro, Kessler and McGrath2018). On the other hand, some chronic physical conditions may lead to cognitive impairment via factors such as atherosclerosis, microvascular changes and inflammatory processes (Biessels et al., Reference Biessels, Staekenborg, Brunner, Brayne and Scheltens2006).

The fact that SCC were still significantly associated with PE after adjustment for all potentially influential factors assessed in this study point to the possibility that SCC and PE are linked via other mechanisms. For example, cognitive deficits may lead to PE by directly affecting the way in which events are interpreted (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, McManus, Brugha, Meltzer, Jenkins and Bebbington2011). Furthermore, incipient brain disorders may underlie both cognitive deficits and PE (Stling et al., Reference Stling, Johansson and Skoog2004). Finally, genetic factors may also play a role and this is an area for future research (Hatzimanolis et al., Reference Hatzimanolis, Bhatnagar, Moes, Wang, Roussos, Bitsios, Stefanis, Pulver, Arking, Smyrnis, Stefanis and Avramopoulos2015).

The strengths of the study include the very large sample size and the inclusion of diverse populations across the globe as well as the use of predominantly nationally representative datasets. However, the study results should be interpreted in light of several potential limitations. First, given that all information was based on self-report, there is potential for reporting bias. Second, it is important to note that the aim of the study was to quantify the degree to which potentially influential factors may explain the association between SCC and PE, without differentiating the factors as mediators or confounders. Mediation and confounding are identical statistically and can only be distinguished on conceptual grounds (MacKinnon et al., Reference MacKinnon, Krull and Lockwood2000). Third, we lacked data on cannabis use which has been associated with both cognitive impairment and PE (van Gastel et al., Reference van Gastel, Vreeker, Schubart, MacCabe, Kahn and Boks2014; Mizrahi et al., Reference Mizrahi, Watts and Tseng2017). However, recent studies have found that PE were associated with cognitive impairment even after adjustment for cannabis use (Mollon et al., Reference Mollon, David, Morgan, Frissa, Glahn, Pilecka, Hatch, Hotopf and Reichenberg2016) and that the link between borderline intellectual functioning and psychosis is not mediated by cannabis use (Hassiotis et al., Reference Hassiotis, Noor, Bebbington, Afia, Wieland and Qassem2017). Fourth, we used two questions to assess SCC. There is no consensus on the measure to capture SCC and the measures used in previous studies range from a single question to a complex assessment involving multiple questions. Thus, the results could have differed if a different measure of SCC was used. Next, previous studies have shown that SCC may have a more psychological component than objective cognitive measures (Homayoun et al., Reference Homayoun, Nadeau-Marcotte, Luck and Stip2011), but the association between SCC and PE remained significant even after adjustment for mental health factors such as depression and anxiety in our study. In addition, due to lack of data, we were unable to assess the effect of psychiatric medication such as benzodiazepines or lithium which may be more commonly used by individuals with PE, and may impact on cognition. Finally, the cross-sectional design limits the assessment of temporal association and causality.

In conclusion, our study results showed that SCC were associated with higher odds for PE in adults living in LMICs, and this association was particularly pronounced among younger individuals who are at particularly high risk for psychosis. Future longitudinal studies are warranted to understand the temporal association between SCC and PE, and the utility of SCC in predicting future psychosis risk especially among younger individuals. SCC may serve as a simple and cost-effective screening tool as compared with objective cognitive testing in identifying individuals at high risk for future psychosis onset, pending future research.

Author ORCIDs

D. Vancampfort 0000-0002-6998-5659.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796018000744

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used in this study is publically available to all interested researchers through the following website: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/en/.

Financial support

AK's work was supported by the Miguel Servet contract financed by the CP13/00150 and PI15/00862 projects, integrated into the National R + D + I and funded by the ISCIII – General Branch Evaluation and Promotion of Health Research – and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF-FEDER). BS received funding from the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research & Care Funding scheme. These funders had no role in: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.