Introduction

Ethical behavior is a key element of effective leadership (Bass & Avolio, Reference Bass and Avolio1994; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Boer, Chou, Huang, Yoneyama, Shim and Tsai2014; Ferdig, Reference Ferdig2007; Greenleaf, Reference Greenleaf1997). It fosters organizational trust of employees (Kerse, Reference Kerse2021) and correlates with employee outcomes such as reductions in burnout, deviant behavior, and turnover (Demirtas & Akdogan, Reference Demirtas and Akdogan2015; Sarwar, Ishaq, Amin, & Ahmed, Reference Sarwar, Ishaq, Amin and Ahmed2020). Consequently, organizations that cultivate ethical leaders are more likely to create positive work environments (Mayer, Aquino, Greenbaum, & Kuenzi, Reference Mayer, Aquino, Greenbaum and Kuenzi2012).

Cultural roots and regional distinctions of Eastern ethical leadership

Ethical leadership is predominantly viewed through a Western lens, creating several issues (Eisenbeiss, Reference Eisenbeiss2012). First, Western employees are more individualistic and short-term oriented while Eastern employees are more collectivistic and long-term focused (Brewer & Chen, Reference Brewer and Chen2007). The Eastern emphasis on collectivism fosters strong social exchanges between leaders and followers. Second, Eastern ethics are rooted in religious beliefs like Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, and Hinduism (Filatotchev, Wei, Sarala, Dick, & Prescott, Reference Filatotchev, Wei, Sarala, Dick and Prescott2020), which emphasize environmental care and responsibility (Christensen, Reference Christensen2014; Dorzhigushaeva & Kiplyuks, Reference Dorzhigushaeva and Kiplyuks2020). This implies that Eastern ethical leaders should reflect these values. Finally, the East’s rising economic and political influence in contrast to West’s decline (Cox, Reference Cox2012) emphasizes the understanding of Eastern ethical leadership. Despite the significance, the field remains fragmented, signaling the need for a systematic review to explore and define the unique dimensions of Eastern ethical leadership.

We focus on the South Asian (e.g., Bangladesh and India, etc.), Southeast Asian (e.g., Malaysia and Indonesia, etc.), and the East Asian (e.g., China and Japan, etc.) regions excluding the Middle Eastern and Central Asian countries. We excluded the Middle Eastern countries due to distinct perspectives on gender equality and governance (Rizzo, Abdel-Latif, & Meyer, Reference Rizzo, Abdel-Latif and Meyer2007), and Central Asian countries due to historical ties to the USSR and their Western influences (Becker, Reference Becker1991).

The Asian regions in this review have several distinguishing characteristics. Southeast and East Asian regions with Confucian influence emphasize group orientation (Wei & Li, Reference Wei and Li2013). South Asian cultures characterizing human heartedness also value group cohesion (Gupta, Surie, Javidan, & Chhokar, Reference Gupta, Surie, Javidan and Chhokar2002). This contrasts with Western cultures where individualism and self-dependence are more common (Ashkanasy, Trevor-Roberts, & Earnshaw, Reference Ashkanasy, Trevor-Roberts and Earnshaw2002). Asian cultures typically have high power distance compared to Western cultures, affecting leadership approaches (Ashkanasy et al., Reference Ashkanasy, Trevor-Roberts and Earnshaw2002; Wei & Li, Reference Wei and Li2013).

Western and Eastern thinking differs based on philosophical viewpoints (Suen, Cheung, & Mondejar, Reference Suen, Cheung and Mondejar2007). Western philosophy largely follows Aristotle, focusing on virtue ethics in analyzing human behavior (Xiao, Reference Xiao and B1996). In contrast, East and Southeast Asian cultures often draw from teachings of Mencius, Confucius, and Laozi (Alzola, Hennig, & Romar, Reference Alzola, Hennig and Romar2020; Suen et al., Reference Suen, Cheung and Mondejar2007). These differences impact ethical expectations. For example, employees from Confucian cultures may expect leaders to act as familial role models, exhibiting care, moral discipline, and a sense of community, whereas Western employees typically expect a focus on individual rights (Forsyth, O’Boyle, & McDaniel, Reference Forsyth, O’Boyle and McDaniel2008; Franciois, Reference Franciois2004; Suen et al., Reference Suen, Cheung and Mondejar2007).

Western perspectives in the current literature on ethical leadership

Ethical leadership has evolved from Bass and Steidlmeier’s (Reference Bass and Steidlmeier1999) initial work, branching into various dimensions. For instance, these dimensions include, moral person and moral manager (Brown, Treviño, & Harrison, Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005); ethical guidance, concern for sustainability, and power sharing (Kalshoven, Den Hartog, & De Hoogh, Reference Kalshoven, Den Hartog and De Hoogh2011); as well as temperance, fortitude, prudence, and justice (Riggio, Zhu, Reina, & Maroosis, Reference Riggio, Zhu, Reina and Maroosis2010).

While several scales for ethical leadership exist, Brown et al.’s (Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005) Ethical Leadership Scale (ELS) is widely used in empirical studies (Ahmad, Fazal-e-hasan, & Kaleem, Reference Ahmad, Fazal-e-hasan and Kaleem2020; Chughtai, Byrne, & Flood, Reference Chughtai, Byrne and Flood2015). However, only a few scales are designed to represent characteristics unique to the Eastern context. For instance, Zhu, Zheng, He, Wang, and Zhang (Reference Zhu, Zheng, He, Wang and Zhang2019) Chinese ethical leadership scale strongly resembles ELS. Similarly, Khuntia and Suar’s (Reference Khuntia and Suar2004) Indian ethical leadership scale concentrates on managing people, potentially overlooking other important aspects of ethical leadership such as concern for long-term sustainability.

Cross-cultural studies have shown a Western bias, as evident in the limited representation of Eastern countries. Resick, Hanges, Dickson, and Mitchelson (Reference Resick, Hanges, Dickson and Mitchelson2006) and Eisenbeiss and Brodbeck’s (Reference Eisenbeiss and Brodbeck2014) studies, which include fewer Eastern countries, further exemplify this bias. According to Ng and Feldman (Reference Ng and Feldman2015) 61% of studies utilize the ELS, indicating its broad application due to its simplicity, while only 16% in Asia use a moral leadership scale derived from paternalistic leadership.

Theoretical and practical significance

Exploring Eastern ethical leadership is vital for both theory and practice. Cultural variations suggest Western measures may not fully capture Eastern interpretations. Despite extensive research on ethical leadership outcomes, the lack of scales tailored to Eastern contexts restricts the scope of these studies. Our systematic review examines the dimensions of Eastern ethical leadership, offering insights to develop more culturally appropriate frameworks and scales.

Understanding Eastern and Western differences in ethical leadership is crucial for multinational companies (MNCs) operating in the East. Although Western MNCs are drawn to Eastern regions for resources and cheap labor (Park & Ungson, Reference Park and Ungson2019), business ethics vary significantly between regions (Donleavy, Lam, & Ho, Reference Donleavy, Lam and Ho2008). This divergence requires MNC leaders to grasp Eastern ethical leadership to ensure successful operations in diverse cultural settings.

This systematic review identifies knowledge gaps, pointing to the need for further research by addressing the following research question.

What are the dimensions of Eastern ethical leadership as informed by Eastern cultural and philosophical perspectives and theoretical frameworks?

We describe our review methodology and present our findings in the sections that follow, concluding with a discussion of these results.

Methodology

This systematic review follows the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework, encompassing stages of identification, screening, eligibility, and selection (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow and Brennan2021) to ensure a comprehensive and rigorous review process.

Identification process

Ethical leadership emerged primarily from research in the 1990s (Bass & Steidlmeier, Reference Bass and Steidlmeier1999). Databases like Web of Science, Scopus, Emerald Insight, and ProQuest Management list top-ranking business ethics journals (Albrecht et al., Reference Albrecht, Thompson, Hoopes and Rodrigo2010). However, these databases contain few or no articles on Eastern ethical leadership from before 1990. Therefore, our search focused on articles published in English between 1990 and April 2021.

To identify relevant articles, the initial search keywords were ethical, leadership, and East. Considering that culture, religious beliefs, and philosophical views might influence ethical leadership in Eastern regions (Eisenbeiss, Reference Eisenbeiss2012), these terms were also included in our search for articles published between 1990 and 2021 (with time frame criteria explained later). Synonyms for these keywords were discussed among the research team to ensure comprehensive coverage of key concepts. The complete list of keywords and their synonyms, along with the reasons for their inclusion, can be found in Table 1.

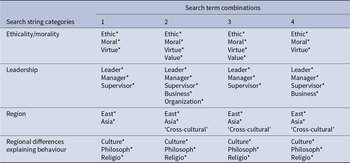

Table 1. The search terms

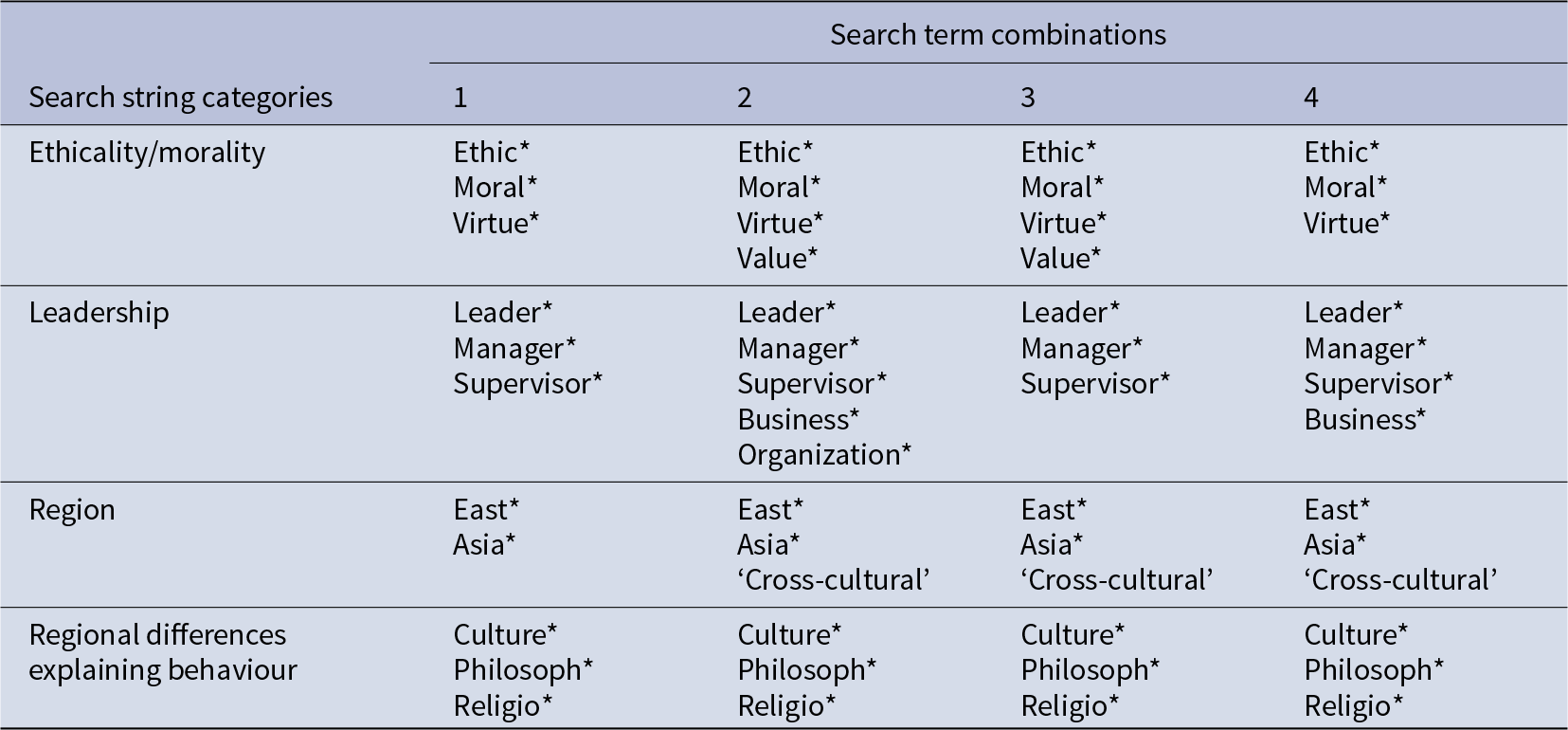

Search term combinations were developed to identify the best combination for the systematic review. Wild cards, truncation marks, and Boolean operators were used to generate the maximum possible word combinations. Table 2 shows the search term combinations used.

Table 2. Search term combinations

Note: Terms represented here within a single cell were combined with the Boolean operator ‘OR’. Each cell in a column was combined with the ‘AND’ operator. The designator * provides results that contain a variation of the keyword. For example, ethic* may mean ethical, ethics, ethically or ethicality.

Initial trials were conducted to understand how the keywords ethical, leadership, and East were applied in the articles. Further analysis led to the selection of combination 3 (see Table 2), as it produced a manageable number of articles while maintaining the focus on the keywords.

Screening and eligibility

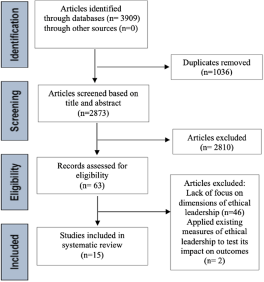

A total of 3,909 articles were identified and reduced to 2,873 after removing the duplicates. These articles underwent screening, first by topic, then by abstract, and finally by full text, resulting in the exclusion of those not clearly related to Eastern ethical leadership (see Fig. 1). We also excluded articles that tested ethical leadership’s impact on outcomes using Western-based measures, focusing instead on conceptualizing Eastern ethical leadership. However, we considered one article adopting the ELS of Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005) because it examined cross-cultural measurement invariance between Eastern and Western cultures. All eligible articles had to focus on conceptualizing ethical leadership in the East or Asia. Accordingly, the final number for the systematic review meeting this criterion was reduced to 15 articles as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA framework.

Details of final selection

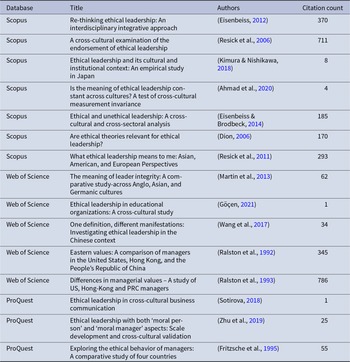

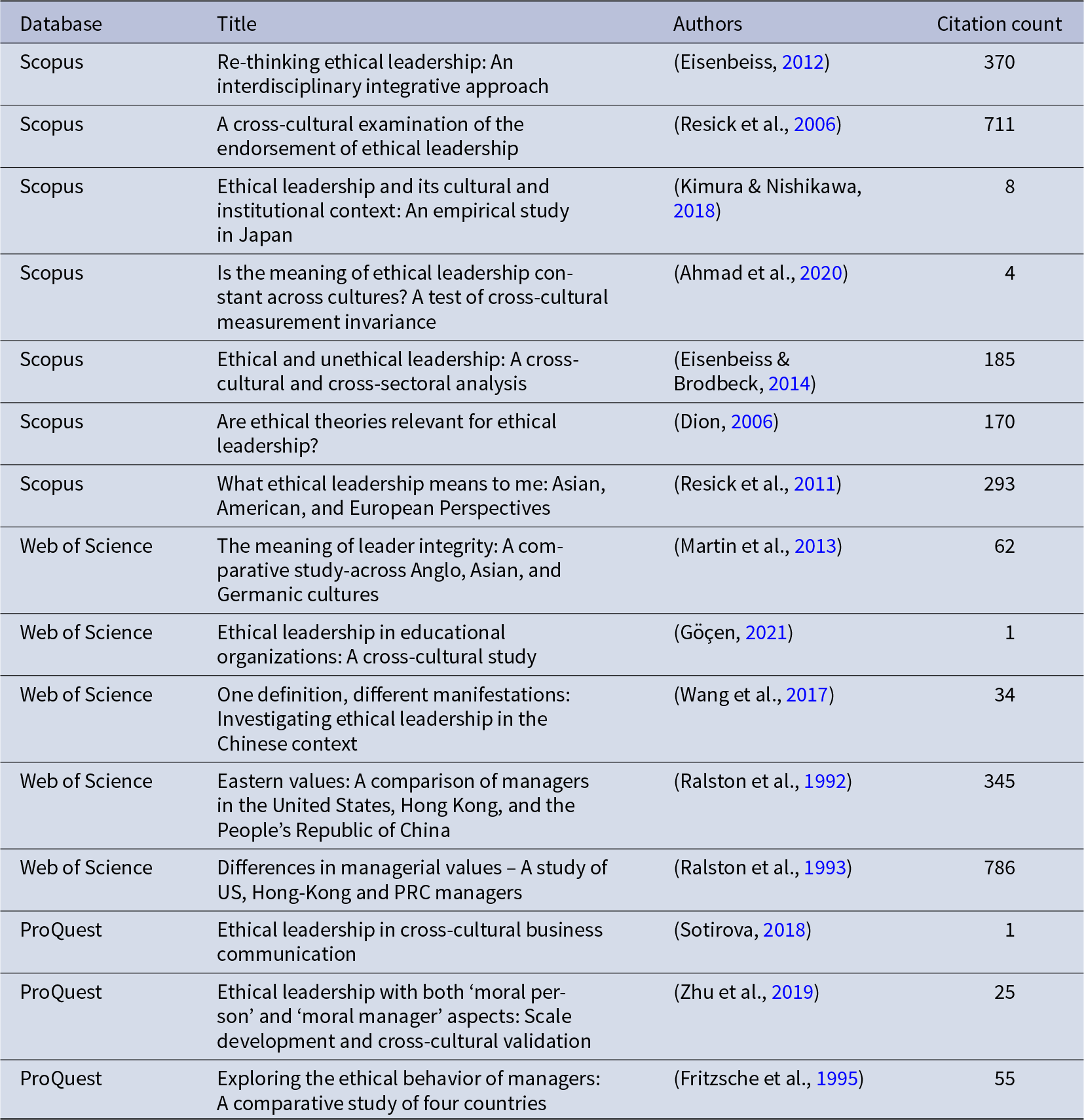

The title, database, authors, year of publication, and the citation counts of the 15 articles finally selected for the analysis are listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Articles selected for the study

General findings

Classifications of articles

The articles were initially analyzed based on authors, keywords, journal types, databases, and whether the study was a review or empirical research. The content analysis then classified them by culture and identified the dimensions of ethical leadership for the East. This was followed by an analysis of the theoretical concepts and philosophical views underpinning these dimensions.

Table 3 shows a demographic analysis of the articles. A notable point is that there is a small pool of researchers in the field. Eisenbeiss (Reference Eisenbeiss2012), Eisenbeiss and Brodbeck (Reference Eisenbeiss and Brodbeck2014), Resick et al. (Reference Resick, Hanges, Dickson and Mitchelson2006, Reference Resick, Martin, Keating, Dickson, Kwan and Peng2011), and Ralston, Gustafson, Elsass, Cheung, and Terpstra (Reference Ralston, Gustafson, Elsass, Cheung and Terpstra1992), Ralston, Gustafson, Cheung, and Terpstra (Reference Ralston, Gustafson, Cheung and Terpstra1993) were the main authors for two articles each. Among the sources, seven articles came from Scopus, five from Web of Science, and three from ProQuest Management. Eleven articles were published after 2010.

The Journal of Business Ethics published five of the articles while other journals contributed one or two each. Three of the 15 articles were conceptual papers by Dion (Reference Dion2006), Eisenbeiss (Reference Eisenbeiss2012), and Sotirova (Reference Sotirova2018) while the remaining 12 were empirical studies. Dion’s (Reference Dion2006) paper examined the link between leadership approaches and ethical theories, while Eisenbeiss (Reference Eisenbeiss2012)) and Sotirova (Reference Sotirova2018) conducted cross-cultural analysis of ethical leadership. Eisenbeiss (Reference Eisenbeiss2012) aimed to develop an interdisciplinary integrative approach to conceptualize ethical leadership by comparing the moral philosophy and ethical principles from both Western and the Eastern religions. Sotirova (Reference Sotirova2018) explored how cultural differences between East and West account for variations in perceptions of key elements of ethical leadership.

The 12 empirical studies focused on different cultures (see Fig. 2). Ten of these articles included both Western and Eastern countries, while two focused exclusively on Eastern countries. Two studies employed quantitative analyses, one based on GLOBE (Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness) project data encompassing 62 societies, and the other cross-culturally testing Brown et al.’s (Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005) ELS. Remarkably, eight studies utilized qualitative interviews or combined interviews with surveys to develop ethical leadership measurement scales. The United States was the most researched Western country in cross-cultural studies, having a presence in eight articles. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was the most researched Eastern country, appearing in six articles. Germany and Hong Kong were found in four studies, while 24 other countries were represented in less than four studies.

Figure 2. Culture-based classification of articles.

Cultural contributions to ethical leadership

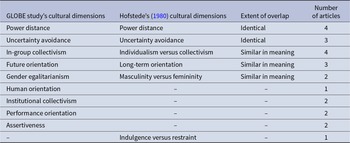

Cultural dimensions describe how different cultural groups differ in terms of psychological characteristics such as values, beliefs, self-concepts, personality, and actions (Smith & Bond, Reference Smith, Bond, Zeigler-Hill and Shackelford2020). Only four articles explored cultural dimensions in depth examining power distance, individualism versus collectivism (or in-group collectivism), uncertainty avoidance, and future orientation (as presented in Table 4). Only two research groups focused on Eastern perspectives: Kimura and Nishikawa (Reference Kimura and Nishikawa2018) and Resick et al. (Reference Resick, Martin, Keating, Dickson, Kwan and Peng2011). Kimura and Nishikawa (Reference Kimura and Nishikawa2018) identified high collectivism in Japanese context. In summarizing the GLOBE study, Resick et al. (Reference Resick, Martin, Keating, Dickson, Kwan and Peng2011) assert that Confucian Asians exhibit high in-group collectivism, institutional collectivism, and performance orientation. Resick et al. (Reference Resick, Martin, Keating, Dickson, Kwan and Peng2011) suggested ethical leaders of those cultures should prioritize organizational needs, consider sustainability and long-term effects, safeguard society’s interests, and foster teamwork. However, their findings require validation in other Asian countries such as South Asia as the GLOBE study focused primarily on East Asia and Southeast Asia. Additionally, cultural dimensions may vary within the same cluster: power distance is high in China (Resick et al., Reference Resick, Martin, Keating, Dickson, Kwan and Peng2011) and moderate in Japan (Kimura & Nishikawa, Reference Kimura and Nishikawa2018), warranting further investigations into ethical leadership in Eastern cultures.

Table 4. Cultural contributions to ethical leadership

Eastern understandings and dimensions of ethical leadership

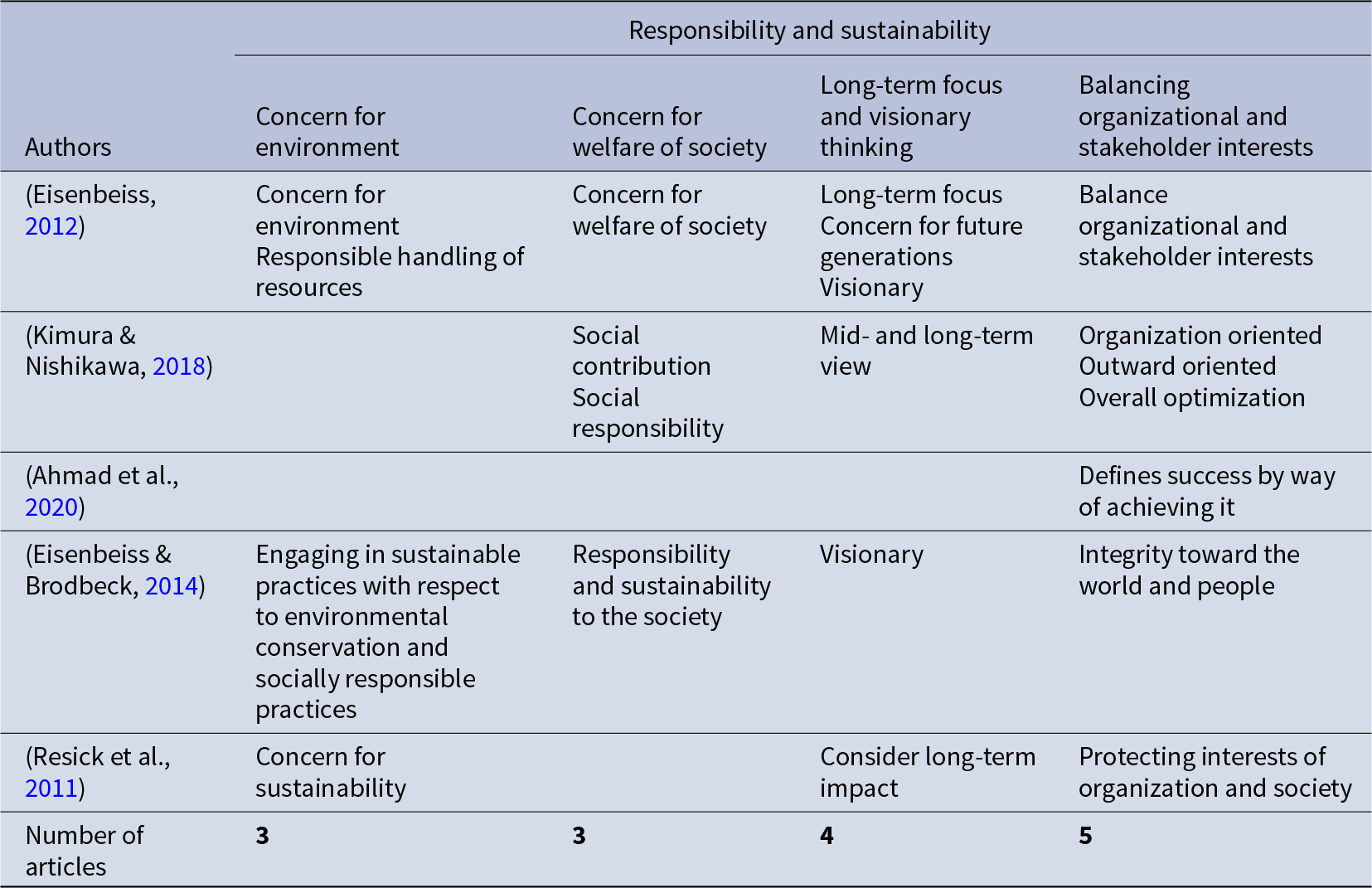

Two articles compared cross-cultural managerial value systems (Ralston, Giacalone, & Terpstra, Reference Ralston, Giacalone and Terpstra1994; Ralston, Gustafson, Cheung, & Terpstra, Reference Ralston, Gustafson, Cheung and Terpstra1993). Dion (Reference Dion2006) examined ethical theories underpinning leadership, and Fritzsche et al. (Reference Fritzsche, Huo, Sugai, Tsai, Kim and Becker1995) explored the ethical behavior of leaders by subjecting Donaldson and Dunfee’s (Reference Donaldson and Dunfee1994) social contracts theory. These four articles focused on providing a theoretical and conceptual underpinning to ethical leadership rather than identifying its dimensions. The remaining 11 articles identified ethical leadership dimensions in Eastern or cross-cultural contexts. This analysis produced five key dimensions and 23 items to explain ethical leadership as detailed in Table 5. Empirical support for these dimensions and items is presented in Tables 6–10.

Table 5. Dimensions and items of ethical leadership identified from the systematic review

Table 6. Empirical support for items of concern for people

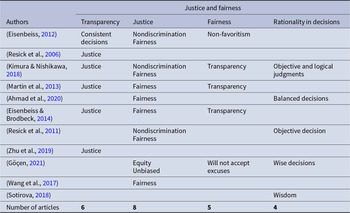

Table 7. Empirical support for items of justice and fairness

Table 8. Empirical support for items of responsibility and sustainability

Theories and concepts underpinning ethics in leadership

The theories in the articles can be broadly classified as social sciences and ethics oriented. Social science-related theories tend to provide an underpinning to the leader’s behavioral aspects such as actions, decision making and behaviors while ethics-related theories focus on their cognition, rationality, and psychological processes. Among the 15 articles in this review, 5 addressed social science theories and 9 focused on ethics in leadership.

Table 9. Empirical support for items of character

Table 10. Empirical support for items of compliance and accountability

The five social science–related theories identified in the literature help conceptualize different dimensions of ethical leadership. Bandura’s (Reference Bandura1986) Social Learning Theory (SLT) links ethical role modeling to learning by observing others (Eisenbeiss, Reference Eisenbeiss2012). Integrative Social Contracts Theory suggests that moral and/or political obligations are contingent on societal agreements (Donaldson & Dunfee, Reference Donaldson and Dunfee1994), explaining the discrepancies in conduct and rationale of leaders (Fritzsche et al., Reference Fritzsche, Huo, Sugai, Tsai, Kim and Becker1995). The Implicit Theory of Leadership explores how factors such as information processing, social perceptions, organizational culture, and executive leadership influence followers’ views (Lord & Maher, Reference Lord and Maher2002). Ahmad et al. (Reference Ahmad, Fazal-e-hasan and Kaleem2020) noted that while the core meaning of ethical leadership is consistent across cultures, its enactment may differ across cultures. Rawls’ (Reference Rawls1971) Theory of justice focuses on a universally accepted system of fairness and methods for accomplishing it. Kimura and Nishikawa (Reference Kimura and Nishikawa2018) found that Institutional theory in Japanese organizations supports ethical leaders’ accountability and collective orientation.

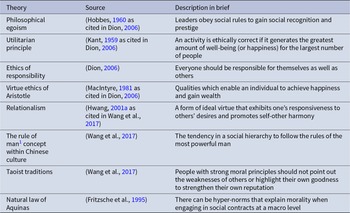

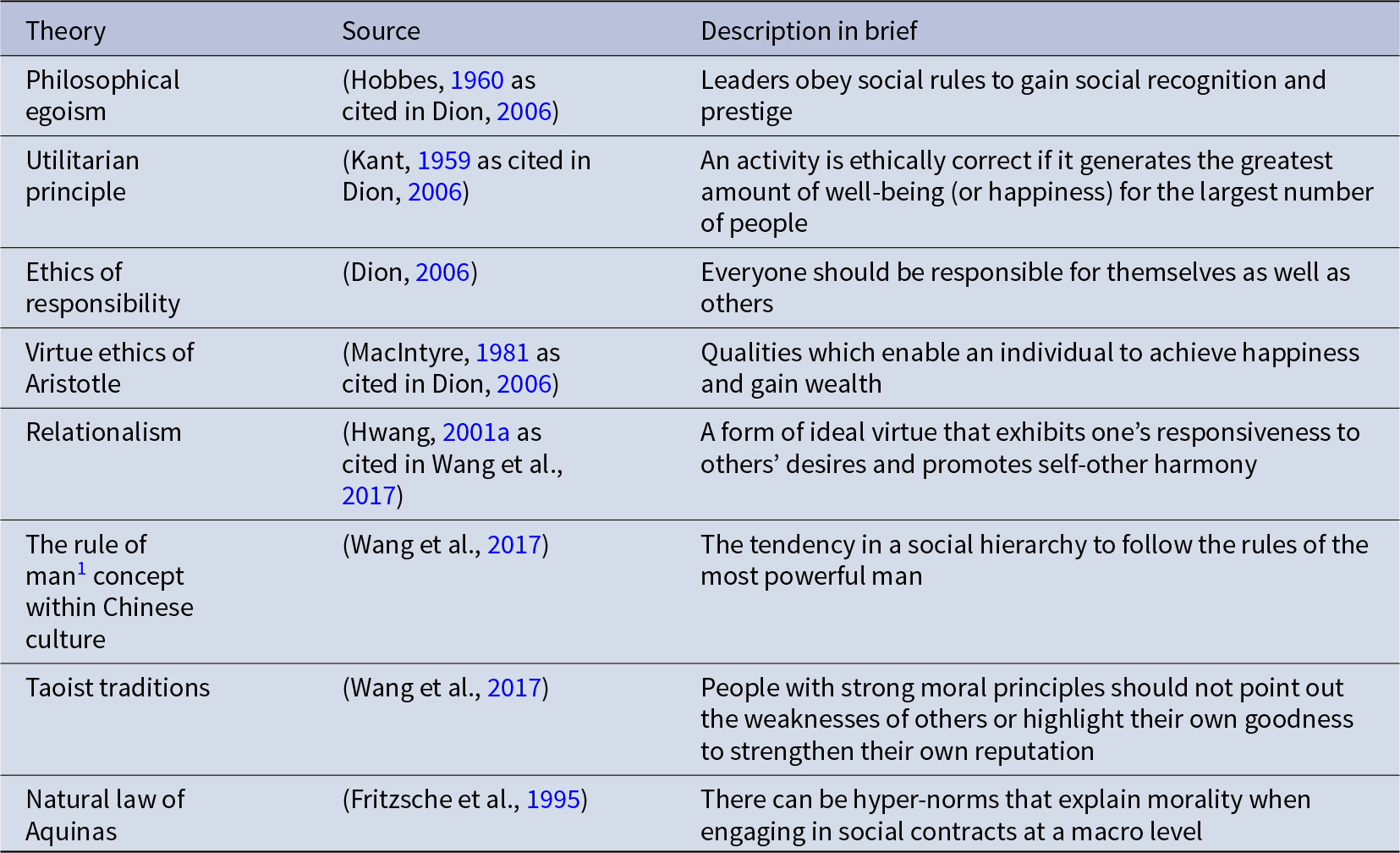

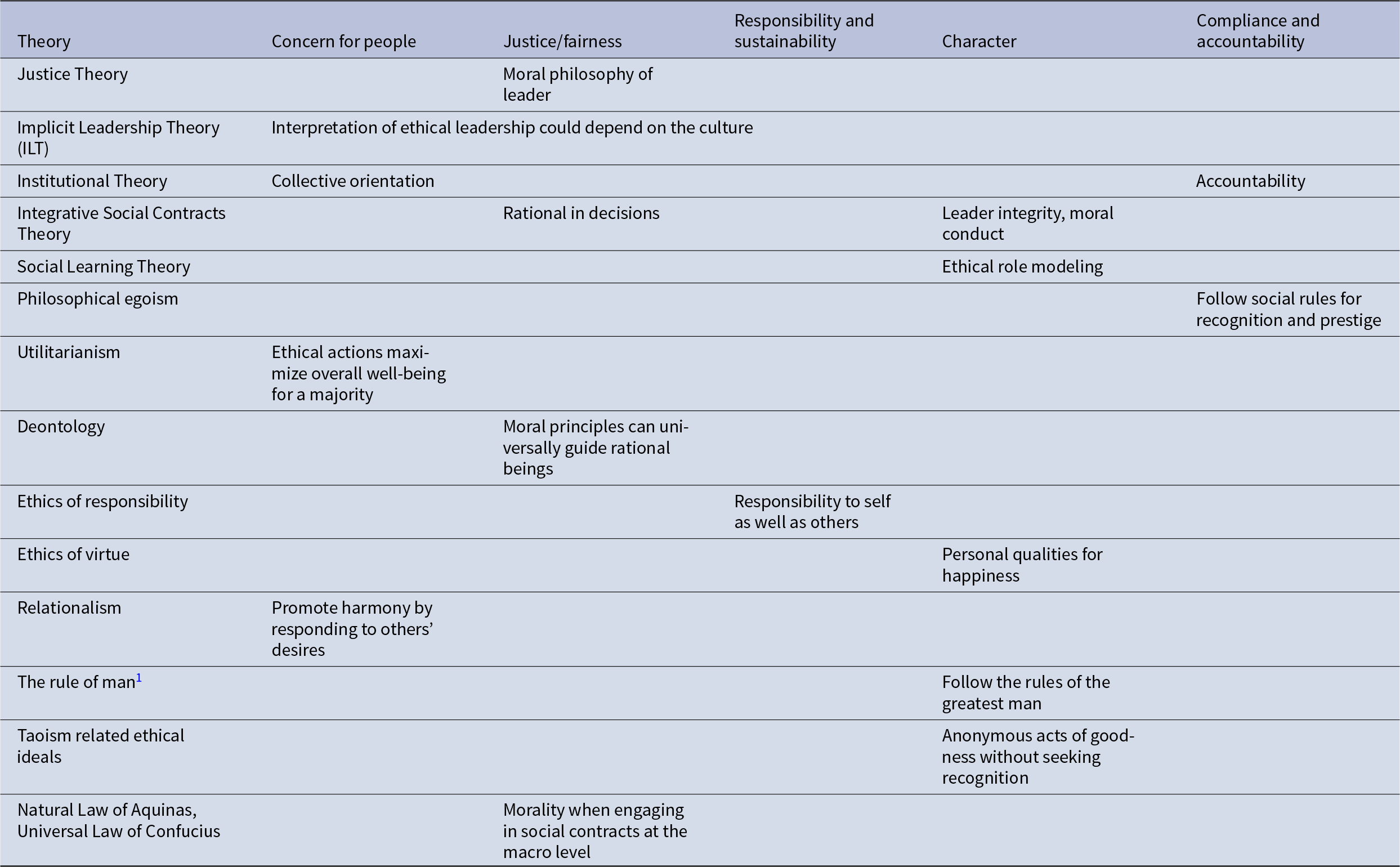

Only four articles in this systematic review supported nine ethical theories related to leadership. According to Knights and O’Leary (Reference Knights and O’Leary2006), ethical leadership is ‘ethical’ because it reflects one or more ethical theories. Ethical theories underlying various leadership qualities were mostly discussed by Dion (Reference Dion2006). This section briefly describes these theories (see Table 11) and explains how they support the identified dimensions of ethical leadership (see Table 12).

Table 11. Ethical theories discussed in articles

Table 12. Theories and concepts supporting each dimension of ethical leadership

These ethical theories provide a foundation to explain the dimensions of ethical leadership. Utilitarianism and deontology principles underpin community/people orientation which encompasses motivational and encouraging/empowering aspects of ethical leadership. Deontology and ethics of virtue support character traits in ethical leaders, as noted by Resick et al. (Reference Resick, Hanges, Dickson and Mitchelson2006). The ethics of responsibility support the responsibility and sustainability orientation of ethical leaders. The concepts of relationalism, the rule of man,Footnote 1 and Taoism-related ethical ideals support ethical character in a leader’s conduct. Aquinas’s natural law and Confucius’s universal law underpin the character and people-orientation of an ethical leader.

Philosophical contributions to ethical leadership

Seven articles identified philosophical views underpinning ethical leadership, with eight philosophers in total mentioned. Notably, six of the articles referred to Confucius. Both Eastern and Western philosophers emphasized the balanced leadership behavior. Aristotle’s doctrine of golden mean suggests that perfection or virtue sits midway between the vices of deficiency and excess (Lawrenz, Reference Lawrenz2021). Plato’s cardinal virtue of temperance, which includes self-mastery and balanced behavior, aligns with this doctrine (Eisenbeiss, Reference Eisenbeiss2012). In the Eastern context, Confucius describes this balance as perfect equilibrium and harmony (Rainey, Reference Rainey2010). Buddhism’s ‘Middle Way’ similarly advocates a blend of active, sincere external action with a calm, accepting attitude on the inside (Vallabh & Singhal, Reference Vallabh and Singhal2014). Confucian as well as Aristotelian teachings on ethical leadership emphasize the leader’s development as a moral and virtuous person (Lawton & Páez, Reference Lawton and Páez2015; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Zheng, He, Wang and Zhang2019).

A leader’s concern for people was recognized by three philosophers. The golden rule of Confucius primarily focuses on a ruler’s responsibility to care for the ruled (Lee, Reference Lee2022) encouraging subordinates to build their conduct (anren). Similarly, the Chinese philosopher Laozi defined effective leaders as those who prioritize the well-being of their group (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Zheng, He, Wang and Zhang2019). In contrast, from a Western perspective, Kant’s categorical imperative suggests that duty cannot be marginally balanced with self-interest-it must be the central focus (White, Reference White2004). As such, the human orientation of an ethical leader can be recognized as a duty. While this leans more toward deontology than utilitarianism, an ethical leaders’ duty to care for the followers can still be viewed as a prime importance. These philosophical views indicate that both Eastern and Western philosophers stress a leader’s duty to care for followers, with Eastern philosophers tending to take a more utilitarian approach by prioritizing others’ well-being over duty.

Our systematic review identified one philosopher (Rawls, Reference Rawls1971) proposing justice and fairness as relevant to ethical leadership arguing that everyone has the right to the same fundamental liberties (Eisenbeiss, Reference Eisenbeiss2012). However, further research showed that both Aristotle and Aquinas have considered justice as a cardinal virtue (Riggio et al., Reference Riggio, Zhu, Reina and Maroosis2010). Additionally, Confucian ethics includes respecting the superior for distributive justice and favoring the intimate for procedural justice (Hwang, Reference Hwang2001b). These highlight the recognition of justice and fairness by both Eastern and Western philosophers.

Eastern philosophical views on ethical leadership extend beyond moral conduct and managerial ethics to emphasize environmental and social sustainability. In contrast, Western philosophers focus more on responsible leadership. In the Eastern context, the Indian philosopher Tagore highlighted the harmony between humans and nature, as well as the broader universe (Basu, Reference Basu2018). Similarly, the founders of Confucianism and Taoism, Confucius and Lao Tzu, saw nature and the cosmos as sacred, with Confucius basing his principles of citizenship, leadership, and governance on this respect for the natural world (Guo, Krempl & Marinova, Reference Guo, Krempl and Marinova2017). For guiding ethical behavior in Western philosophy, Jonas (Reference Jonas1979, cf. Eisenbeiss, Reference Eisenbeiss2012) underlined the need of responsibility and sustainability. Accordingly, the Eastern philosophy places a greater emphasis on harmonious relationships with nature, leading to sustainability, while Western philosophy emphasizes responsibility as the path to sustainability.

Discussion

This study highlighted the dearth of research on ethical leadership within an Eastern context. Although widely used in empirical research, the ELS by Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005) is based on the two-dimensional model of moral manager and moral person proposed by Trevino, Hartman, and Brown (Reference Trevino, Hartman and Brown2000), reflecting primarily Western perspectives. However, due to unique cultural traditions, religious beliefs, and philosophical views, Eastern ethical leadership requires a different conceptualization.

Overall findings

Surprisingly, our systematic review across four different databases – Scopus, Web of Science, ProQuest Management, and Emerald Insight – suggests that only 15 articles have examined ethical leadership in Eastern contexts since 1990. Eastern ethical leaders are expected to embody a broader set of characteristics than the moral manager and moral person dimensions defined by Trevino et al. (Reference Trevino, Hartman and Brown2000). For instance, we found that besides the universally accepted ethical leadership traits of honesty and integrity, Eastern leaders are sometimes expected to demonstrate servanthood (see Table 6). The collectivist nature of Eastern cultures may lead subordinates to expect more support and care from their leaders compared to individualistic Western cultures. Our study identifies five key dimensions of Eastern ethical leadership: (1) character, (2) concern for people, (3) justice and fairness, (4) responsibility and sustainability, and (5) accountability and compliance. These are detailed in the following sections. This discussion focuses on etic components of ethical leadership that are globally accepted across cultures and emic ones particularly applicable to Eastern cultures. This systematic review has several implications for theory and practice.

The first dimension, leaders’ characters, can be resembled through five characteristics: honesty, integrity, self-control, modesty, and ethical role modeling. The cross-cultural research of Resick et al. (Reference Resick, Hanges, Dickson and Mitchelson2006) and Martin et al. (Reference Martin, Keating, Resick, Szabo, Kwan and Peng2013) also found that characteristics such as honesty, trustworthiness, word-action consistency, value behavior consistency, justice and transparency, and sincerity are common across cultures. Similarly, we also consider these characteristics to be cross-culturally relevant.

The second dimension, concern for people, encompasses altruism, openness and flexibility, empathy and understanding, empowerment and participation, team building and providing directions, and consideration and respect. However, cross-cultural differences are evident. Resick et al. (Reference Resick, Hanges, Dickson and Mitchelson2006) found that altruism was highest in Southeast Asia followed by sub-Saharan Africa and Confucian Asia. Openness and flexibility of a leader is expected more in the United States and Ireland compared to China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan (Resick et al., Reference Resick, Martin, Keating, Dickson, Kwan and Peng2011). Chinese societies, rooted in Confucian philosophy, typically do not prioritize a leader’s openness and flexibility, aligning more with paternalistic leadership (Cheng, Chou, & Farh, Reference Cheng, Chou and Farh2000, cf. Resick et al., Reference Resick, Martin, Keating, Dickson, Kwan and Peng2011), characterized by authoritarianism (Cheng, Chou, & Wu, Reference Cheng, Chou and Wu2004). Nevertheless, Eisenbeiss and Brodbeck’s (Reference Eisenbeiss and Brodbeck2014) cross-cultural study indicated that Eastern ethical leadership is more associated with openness to ideas held by others and humility than in Western cultures. This suggests that while Eastern ethical leaders may consider subordinate input, they may retain the final decision-making authority without necessarily explaining their rationale.

Participatory management style is more accepted in the East compared to the Western preference for transactional management (Eisenbeiss & Brodbeck, Reference Eisenbeiss and Brodbeck2014). Consideration and respect are key traits of ethical leadership in both Eastern and Western cultures (Resick et al., Reference Resick, Martin, Keating, Dickson, Kwan and Peng2011) and specifically with respect to Asian cultures as well (Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Fazal-e-hasan and Kaleem2020; Kimura & Nishikawa, Reference Kimura and Nishikawa2018). As a result, Eastern ethical leaders may be more altruistic and empathetic, encouraging follower participation, even though they may retain final decision-making authority.

Our third dimension is Justice, Fairness, and nondiscriminatory treatment. These characteristics were found across both East and West (Göçen, Reference Göçen2021; Resick et al., Reference Resick, Martin, Keating, Dickson, Kwan and Peng2011) and proposed as core characteristics of ethical leadership by Eisenbeiss (Reference Eisenbeiss2012). Similarly, objective and wise decision-making is recognized in both Western and Eastern cultures as a characteristic of an ethical leader (Göçen, Reference Göçen2021; Resick et al., Reference Resick, Martin, Keating, Dickson, Kwan and Peng2011).

We found concern for responsibility and sustainability as the fourth dimension of ethical leadership. Eisenbeiss (Reference Eisenbeiss2012) recognized the significance of a leader’s responsibility and environmental consciousness and proposed it as a dimension of ethical leadership, later validated through qualitative studies (Eisenbeiss & Brodbeck, Reference Eisenbeiss and Brodbeck2014). Additionally, Asian religions have fostered a greater environmental consciousness (Eisenbeiss, Reference Eisenbeiss2012). As such, concern for the environment could be regarded as a core element of Eastern ethical leaders.

Accountability and compliance represent our fifth dimension of ethical leadership. Resick et al. (Reference Resick, Martin, Keating, Dickson, Kwan and Peng2011) cross-culturally validated accountability, compliance, and promoting ethical behavior among subordinates and holding subordinates accountable as characteristics of ethical leadership. Martin et al. (Reference Martin, Keating, Resick, Szabo, Kwan and Peng2013) identified responsibility toward others and adherence to rules as dimensions of leaders’ integrity across Eastern and Western cultures. Kimura and Nishikawa (Reference Kimura and Nishikawa2018) and Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Zheng, He, Wang and Zhang2019) also highlighted accountability and compliance in Japanese and Chinese contexts respectively. However, in Eastern societies, ethical leaders may not only follow organizational rules but also respect social norms. Eisenbeiss and Brodbeck (Reference Eisenbeiss and Brodbeck2014) emphasized that ethical leaders go beyond formal regulations to act for the benefit of others.

Theoretical implications

The cross-cultural differences in conceptual definitions of ethical leadership were highlighted by many scholars (Eisenbeiss, Reference Eisenbeiss2012; Resick et al., Reference Resick, Hanges, Dickson and Mitchelson2006). Authors have identified cultural parameters to guide cross-cultural comparisons. Individualism and collectivism, for example, explain the integration of individuals into primary groups across cultures. Leaders in collectivist cultures are more likely than leaders in individualist societies to serve society at large (Robertson & Fadil, Reference Robertson and Fadil1999). These differences are important as they shape how leaders treat their followers, approach ethical dilemmas, and make decisions, ranging from regular operations to major business decisions.

Eisenbeiss (Reference Eisenbeiss2012) critically analyzed Eastern philosophies and religious views proposing four ethical leadership dimensions: human orientation, justice orientation, responsibility and sustainability orientation, and moderation orientation. Our systematic review includes seven articles published after Eisenbeiss (Reference Eisenbeiss2012) (see Table 3), providing further scrutiny of her findings. Three of the ethical leadership dimensions from our systematic review – concern for people, justice and fairness, and responsibility and sustainability – align with Eisenbeiss’s (Reference Eisenbeiss2012) orientations of human, justice, and responsibility and sustainability. However, for her moderation orientation, our review suggests an alternative classification of self-control and balanced behavior. Self-control which includes agreeableness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability (Olson, Reference Olson2005) can be considered a personal characteristic of ethical leaders. Balancing short- and long-term goals within the moderation orientation aligns with an ethical leader’s sustainability focus, requiring the evaluation of societal impacts (Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2004). Accordingly, we find that the two main dimensions of moderation orientation, self-control, and balanced behavior towards short and long-term views, can be addressed separately within the character and the sustainability and responsibility aspects of ethical leadership.

Additionally, we found empirical evidence supporting compliance and accountability as a dimension of ethical leadership. Eisenbeiss and Brodbeck (Reference Eisenbeiss and Brodbeck2014) suggest that ethical leaders should be more value-oriented than compliance-oriented, displaying humanity, honesty, justice, and responsibility and sustainability. However, Kimura and Nishikawa’s (Reference Kimura and Nishikawa2018) study in Japan recognized the importance of accountability and compliance in the Eastern context. Eisenbeiss and Brodbeck (Reference Eisenbeiss and Brodbeck2014) view compliance and accountability as minimum benchmarks, with ethical leadership extending beyond mere rule-following. Tyler, Dienhart, and Thomas (Reference Tyler, Dienhart and Thomas2008) propose that a values-based strategy is more effective in promoting rule adherence, but Geddes (Reference Geddes2017) warns that when ethical choices are unclear, employees may simply follow the rules. This indicates that a values-based approach alone may not suffice – compliance and accountability may also have to be considered.

Cross-cultural research indicates that the five characteristics we associate with the character of an ethical leader are common to both East and West, though their interpretation may differ. Members in Eastern collective cultures are linked by emotional predispositions, shared interests, fate, and collectively agreed social engagements. Therefore, the character of an Eastern ethical leader may be perceived as modest, charismatic, visionary, and displaying servanthood besides universally accepted effective leadership characteristics of honesty and integrity (see Table 9). Confucius’s teachings, which emphasize harmonious relationships, further support these characteristics (Eisenbeiss, Reference Eisenbeiss2012).

Our findings can also be compared with Den Hartog’s (Reference Den Hartog2015) analysis of ethical leadership which follows an organizational psychology perspective. Den Hartog (Reference Den Hartog2015) found that while the emphasis on specific characteristics differs across cultures, the general concept of ethical leadership is represented by comparable categories of traits and behaviors. Drawing from cross-cultural research of Eisenbeiss and Brodbeck (Reference Eisenbeiss and Brodbeck2014) and Resick et al. (Reference Resick, Martin, Keating, Dickson, Kwan and Peng2011), Den Hartog (Reference Den Hartog2015) explored the cultural differences in ethical leadership. However, specific dimensions of Eastern ethical leadership are not detailed; instead, the focus is on potential outcomes and moderators related to ethical leadership.

Several ethical theories help explain Eastern ethical leadership. Deontology (Kant, Reference Kant1959, cf. Dion, Reference Dion2006), and SLT (Bandura, Reference Bandura1986) serve as foundations for dimensions of ethical leadership. In Eastern contexts, deontology may mean that leaders not only follow organizational rules but also adhere to social norms, reflecting philosophical egoism (Hobbes, Reference Hobbes1960, cf. Dion, Reference Dion2006). The social recognition developed by following social norms may support in developing the charisma of a leader in collectivist societies (Resick et al., Reference Resick, Martin, Keating, Dickson, Kwan and Peng2011). However, in Taoist-influenced cultures, leaders should avoid building charisma through philosophical egoism. Taoist tradition discourages exaggerating one’s virtues or criticizing others to gain reputation (Wang, Chiang, Chou, & Cheng, Reference Wang, Chiang, Chou and Cheng2017). This aligns with Wang, Chen, Wang, Lin and Tseng (Reference Wang, Chen, Wang, Lin and Tseng2022) who suggest that in Taiwan, Taoist-oriented leaders are more successful with ethical role modeling than through explicit ethical guidance. Confucian virtue ethics emphasize harmonious social relationships, fitting with collectivist societies, while Aristotle’s approach, which rejects a familial spirit in organizations, does not (Koehn, Reference Koehn2020). The concept of relationalism (Hwang, Reference Hwang2001a), a Chinese tradition, is applicable to other Eastern cultures with high collectivism, focusing on societal harmony.

Practical implications

Leaders working with multinational stakeholders can gain insights into ethical leadership expectations by understanding the significance of various themes. Our systematic review identified five dimensions representing Eastern ethical leadership, offering benchmarks for assessing ethical leadership within a culture. Western leaders operating in Eastern cultures are encouraged to carefully assess the levels and forms of collectivism in their operational context. Some Eastern cultures may require leaders to be altruistic and empathetic, while openness and flexibility may depend on the prevailing power distance. Therefore, leaders need to determine how to integrate these traits into their management style. In Eastern cultures, Western leaders may need to demonstrate charisma and humility and understand that their moral framework may differ from the value systems in these cultures. This understanding helps avoid actions that contradict cultural norms, which could affect a leader’s acceptance. Accountability and compliance with rules and regulations are best promoted through a strong value system. Therefore, leaders should use a values-based approach to guide ethical behavior, supplementing with clear rules when values alone do not offer sufficient guidance.

This research has ramifications for multinational human resource management practices and cross-cultural leadership training. Properly aligning a firm’s management practices with the national culture can offer multinational firms a significant competitive edge. Understanding cultural dimensions based on Hofstede (Reference Hofstede1980) or Schwartz (Reference Schwartz2007) can guide managers in developing human resource and marketing strategies that align with the national culture, reducing potential conflicts from cultural mismatches. For instance, if an expatriate leader of an MNC understands that the national culture values collectivism, praising a group for their performance instead of individuals can increase the leader’s acceptance, as group conformity is valued(Weaver, Reference Weaver1993, cf. Trevino & Nelson, Reference Trevino and Nelson2014).

Limitations and future research directions

This study has limitations that should be carefully considered when interpreting the results from our systematic review. These limitations also suggest areas for future research. There is an inexact comparability of search strings between the different databases employed. This inconsistency arises from variations in database search fields. In Scopus and ProQuest Management, the search was based on the title, abstract, and keywords, while in Web of Science, it was based on the topic. Readers are therefore advised that there could be further explanations on religious beliefs, philosophical views, and ethical theories that underpin the dimensions of ethical leadership. For future studies, they can conduct a more focused search under those topics. Doing so will enable a more comprehensive understanding of ethical leadership in the Eastern context.

Our initial focus encompassed South Asian and Southeast Asian countries but, due to the absence of relevant studies from those regions, our attention shifted primarily to Eastern countries with Confucian influence (China, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Korea). Consequently, Eastern countries with Buddhist cultures such as Thailand, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka, and Islamic cultures such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Maldives, were not included in the research for conceptualizing ethical leadership. This disproportionate focus on Confucian-influenced countries and limited exploration of Buddhist and Islamic-influenced countries can hinder generalization of the identified ethical leadership traits across the broader Eastern context.

Our systematic review found that most scales for measuring ethical leadership are developed in the West, despite significant differences between Eastern and Western perspectives. As research progresses, there is considerable opportunity to develop a new ethical leadership scale that reflects the Eastern context. Future studies could explore value-based and compliance-based approaches to ethical leadership in Eastern cultures, as both were found to be relevant across different cultural settings. Given the variations in virtue ethics between individualistic and collectivist societies, examining the applicability of different ethical theories to Eastern leadership is another potential research avenue. Finally, future work could assess the relevance of Culturally Implicit Leadership theories to various Eastern leadership contexts, offering deeper insights into effective leadership across diverse cultures.

Conclusion

Eastern ethical leaders are expected to consider a broader perspective when addressing ethical dilemmas. Their approach is influenced by common religious teachings like Buddhism and Hinduism, which emphasize a holistic approach. Western and Eastern perspectives of leadership ethics may differ due to differences of cultures, religious beliefs, and philosophical views. Yet, Eastern ethical leadership has not been researched with an aim to understand it conceptually. This systematic review fills the gap by proposing five dimensions for Eastern ethical leadership, derived from empirical and cross-cultural studies involving Eastern countries. Character, concern for people, justice and fairness, responsibility and sustainability, and accountability and compliance were proposed as dimensions of ethical leadership for the East. This finding supports the conceptual understanding of Eastern ethical leadership as differences in culture, religious beliefs and philosophical views suggest Western measures of ethical leadership may not fit into the East. We have provided several directions for future research based on our findings.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Nadeeja, a PhD student at the University of Waikato, has dedicated her research journey to exploring nuanced dimensions of Eastern Ethical Leadership. This systematic review reflects the culmination of her effort, contributing to the discourse on leadership ethics within the cultural context of the East.

Maree is a senior lecturer at the University of Auckland. Prior to joining the University of Auckland she worked as a senior lecturer at the University of Waikato, Hamilton New Zealand. Maree is a Fellow of the NZ Psychological Society, a Fellow of the Positive Organisational Behavior Institute (USA), and her research and consultancy spans three clusters in Leadership that intersect. These are (1) leadership neuropsychology/mindset of high performance, (2) the impact of this on employee well-being /positive psychology at work, and (3) cross-cultural particularly Māori leadership and employee well-being. Maree specifically examines how leaders’ psychological mindsets are contagious in organizations and the impact of this on employee and organizational outcomes. Maree’s research has highlighted to international audiences, the value of understanding and resourcing, psychologically, leaders, and the importance of this for employees and organizations as they navigate today’s complex and difficult business environments.

Hataya is a senior lecturer in Human Resource Management at the University of Waikato, New Zealand. She received her PhD in Management (Organisational Behaviour) from the Australian National University. Hataya is a research active faculty with publications in international outlets, such as Journal of Vocational Behavior, Journal of Career Assessment, Journal of Management and Organization, and Handbook of Organizational Politics (2nd Edition).

Amanda is a lecturer in innovation and strategy at Waikato Management School, at the University of Waikato, New Zealand, and an AI & Data Consultant. She is passionate about the adoption of artificial intelligence, and the ways it can be leveraged in business and in research. Amanda teaches business strategy and researches the health of entrepreneurs via innovative research methods. Previous to arriving at the University of Waikato she worked at the New Zealand Centre for SME Research, held a Visiting Researcher position in Chile (PUC, School of Engineering), and was awarded her PhD at the Institute of Work Psychology (Sheffield, UK).