Introduction

In the rich history of the Indian Ocean World, maritime trade linked polities and societies across vast distances, facilitating the exchange of commodities, ideas and cultural practices in the pre-modern era (Abu-Lughod Reference Abu-Lughod1989; Chaudhuri Reference Chaudhuri1990; Wade Reference Wade2009; Alpers Reference Alpers2014; Pearson Reference Pearson2015; Beaujard Reference Beaujard2019; Schottenhammer Reference Schottenhammer2019). The twelfth and thirteenth centuries AD, in particular, witnessed a surge in maritime activities across Asia, as evidenced by the numerous large shipwrecks from this period, where Chinese porcelain frequently constituted a substantial portion of the cargo (Meng Reference Meng2018). The rising demand for Chinese porcelain spurred the expansion of export-oriented kilns throughout south-east China, resulting in the development of substantial kiln complexes (Zeng Reference Zeng2001; Fujian Museum 2020).

Despite the extensive archaeological evidence documenting porcelain production and trade, the specific trading mechanisms and merchant practices associated with Chinese porcelain remain underexplored due to the lack of detailed information in historical records. Understanding the precise origins of ceramics disseminated along maritime trade routes is crucial for unravelling complex trading dynamics, yet this task proves challenging due to the numerous kiln sites across south-eastern China and the stylistic similarities among porcelain products. Portable x-ray fluorescence (pXRF) analysis has emerged as a pivotal technique for tracing the origins of these traded porcelains (Cui et al. Reference Cui, Xu, Qin and Ding2016; Fischer & Hsieh Reference Fischer and Hsieh2017; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Niziolek and Feinman2019). While previous studies have primarily focused on macro-provenance—identifying broader production regions or kiln complexes—this research aims to use pXRF to precisely determine the micro-provenance of Chinese porcelains (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Yang, Chen, Cui, Dussubieux and Wang2021; Li et al. Reference Li, Sun, Ma and Cui2022), refining the focus to subregions or even individual kilns to enhance understanding of porcelain production patterns and maritime trading practices.

This study centres on the Nanhai I shipwreck, the largest and most well-preserved Song-period (AD 960–1279) shipwreck discovered in China to date (Figure 1). Our analysis focuses particularly on qingbai (bluish-white) porcelains presumed to originate from Dehua, a renowned porcelain production centre in Quanzhou, Fujian Province—one of the largest ports in Song-Yuan China (AD 960–1368) and a World Heritage site. Building on recent research that identifies two distinct production subregions within Dehua (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Yang, Chen, Cui, Dussubieux and Wang2021), this study addresses critical questions about the porcelain trade linked to the Nanhai I shipwreck. Specifically, can we determine the micro-provenance of the Dehua-style artefacts? Was there a preference for sourcing porcelain from a specific subregion within Dehua, or was the acquisition more diverse? And, if both subregions within Dehua were involved, can we recognise patterns in the types of porcelain acquired? Through these inquiries, our study aims not only to pinpoint the exact provenance of specific artefacts but also to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the intricate patterns of porcelain production and maritime trade that characterised the medieval world.

Figure 1. Location of the Nanhai I shipwreck and the Dehua kiln site (figure by Wenpeng Xu).

Archaeological background

The Nanhai I shipwreck

The Nanhai I shipwreck, located in the waters 19km south-west of Xiachuan Island in Guangdong Province, China, exemplifies the flourishing maritime and ceramic trade of the twelfth–thirteenth centuries AD (Figure 1). Discovered in 1987, the site was first surveyed by a joint Sino-Japanese underwater archaeology team in 1989 (Li Reference Li2019; Sun Reference Sun and Song2022; Wei Reference Wei2023). Subsequently, from 2001 to 2004, the National Museum of China led seven underwater archaeological investigations (National Center of Underwater Cultural Heritage et al. 2017). In 2007, the entire Nanhai I shipwreck was salvaged and subsequently housed at the Maritime Silk Road Museum of Guangdong in Yangjiang, which was specifically constructed to accommodate this shipwreck and is now the largest shipwreck museum in China. Following more than a decade of meticulous excavation, spanning from 2013 to 2023, over 180 000 artefacts have been recovered, including approximately 160 000 pieces of ceramics, 130 tonnes of iron and an assortment of goldware, silverware and other items (National Center of Underwater Cultural Heritage et al. 2018; Wei Reference Wei2023; Xiao Reference Xiao2023a). Drawing on interdisciplinary dating methods, including identification of a brown-glazed jar inscribed with 淳熙十年 (10th year of the Chunxi reign, or AD 1183) and a Dehua porcelain jar marked with 癸卯 (the Gui Mao year from the Chinese Stem-and-Branch calendar system, likely also corresponding to AD 1183), the ship is believed to have sunk in the late twelfth century, possibly in or shortly after 1183 (Wei Reference Wei2023; Nanyue King Museum 2024). The ship probably sailed from the port of Quanzhou (Sun Reference Sun and Song2022; Wei Reference Wei2023) but its final departure may have been from Guangzhou (Huang & Feng Reference Huang and Feng2021; Xiao Reference Xiao2023b; Nanyue King Museum 2024).

The shipwreck measures approximately 22.1m in length with a maximum width of nearly 9.35m (National Center of Underwater Cultural Heritage et al. 2018). Thirteen transverse bulkheads divide the ship into 14 watertight compartments (C2–C15; the existence of a fifteenth compartment, C1, was disproven upon completion of the excavation; Figure 2), which were further divided by movable plates. The ship features a broad, flat design and a V-shaped cross-section. Its construction showcases a multi-layered plank structure, secured with mortise and tenon joints, iron nails and wooden pegs through riveting techniques, exemplifying the unique shipbuilding methods of the Fujian region.

Figure 2. Layout of the Nanhai I shipwreck, revealing compartments tightly packed with ceramics. Compartments containing Dehua-style ceramics are labelled in red (photograph courtesy of Guangdong Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology).

The predominant artefacts retrieved from the Nanhai I shipwreck are porcelain pieces, encompassing a variety of glaze colours or types such as qingbai, celadon, black-glazed, brown-glazed and low-fired lead-green glazed wares. These porcelains are thought to have originated from various kilns in the Jiangxi, Fujian, Zhejiang and Guangdong provinces. A sizable portion of the qingbai porcelains was identified as Dehua-style wares, primarily through stylistic analysis and supplemented by compositional analysis of selected samples (Cui et al. Reference Cui, Meng, Ma and Zhou2017). While the cataloguing process continues, results from surveys conducted between 1989 and 2004 show that 783 of the 3042 pieces are Dehua-style porcelains (National Center of Underwater Cultural Heritage et al. 2017). Found in all 14 compartments of the ship (Figure 2), these Dehua-style porcelains include diverse forms such as bottles, bowls, boxes, dishes, ewers, jars and plates. In the Nanhai I shipwreck, Dehua-style porcelains were packed using various methods to maximise the limited space available; bowls and plates were commonly stacked in piles, while small bottles were tightly arranged both horizontally and vertically to form a compact configuration, and small jars, boxes and bottles were often used to fill gaps between larger porcelain items or were packed inside larger ceramic vessels (Wei Reference Wei2023). These packing methods mirror a practice described by Song-period scholar Zhu Yu in 萍洲可谈 (Pingzhou Ketan), largely based on his father Zhu Fu's experiences as an official in Guangzhou from 1099 to 1102, noting that “货多陶器, 大小相套, 无少隙地” (the cargo, mainly ceramics, was packed with larger items encasing smaller ones, leaving no space unused) (Zhu Reference Zhu2007: 133).

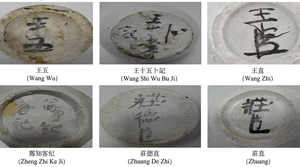

Some Dehua-style porcelains from the Nanhai I shipwreck feature ink inscriptions on their bases. Common inscriptions include Chinese surnames such as 蔡 (Cai), 陳 (Chen), 戴 (Dai), 王 (Wang), 郑 (Zheng) and 莊(Zhuang), characters resembling 直 (Zhi) or 花押 (huaya)—stylised signatures—or a combination of both. The character 直 (Zhi) is often interpreted as a simplified form of 置 (Zhi), denoting procurement or ownership (Huang Reference Huang2007; Lin Reference Lin2018; Chen Reference Chen2020), although some scholars argue that it is a stylised signature (Liang Reference Liang2016; Ishiguro Reference Ishiguro2021). It is important to note that no ceramics from Dehua production sites have been found with such ink inscriptions, suggesting that these markings were likely added during the trading phase. This interpretation is supported by the presence of the same name on products from two different kiln centres in Fujian—Dehua and Cizao—indicating that these names represent traders or owners rather than producers (Nanyue King Museum 2024). Given that the ceramics retrieved from the Nanhai I shipwreck were likely owned by various merchants (Li Reference Li2020; Huang & Feng Reference Huang and Feng2021), these ink marks therefore probably served to label ownership and distinguish the goods of different traders.

Porcelain production at Dehua

The Fujian porcelain industry played a significant role in the global trade dynamics of the twelfth–thirteenth centuries, producing a substantial portion of the Chinese porcelain traded along maritime routes. Located in the mountainous region of Quanzhou, Dehua emerged as a key centre of porcelain production during the Song-Yuan period, with archaeological surveys revealing a total of 42 kiln sites from this era (Figure 3; Xu & Ye Reference Xu and Ye1993; Ho Reference Ho and Schottenhammer2001; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Chen and Chen2011; Meng Reference Meng2017; Xu Reference Xu2021). Excavations at sites such as Wanpinglun, Weilin and Qudougong showcase the extensive scale of kilns operated at Dehua (Fujian Museum 1990; Hu & Yang Reference Hu and Yang2024). The remarkable development in porcelain production at Dehua can be attributed to the locally available rich deposits of high-quality porcelain clay (Gao Reference Gao, Pan and Shen1993) and, crucially, to the rise of Quanzhou as a pivotal maritime trading port in Song-Yuan China (Clark Reference Clark1991; So Reference So2000). Dehua was renowned for its qingbai or white porcelains, which are widely documented along maritime trade routes in East Asia, Southeast Asia and even West Asia (Liu Reference Liu2016; Ding Reference Ding2021). The flourishing porcelain industry at Dehua caught the attention of Marco Polo (Reference Polo1926), who is also believed to have returned with a Dehua porcelain jar from his travels (Lin & Zhang Reference Lin and Zhang2018).

Figure 3. Locations of kiln sites in Dehua County, Quanzhou, Fujian Province, highlighting the delineation of the two subregions: Gaide and Longxun-Sanban (figure by Wenpeng Xu).

While traditional research often regarded the Dehua kiln as a singular entity, recent research has unveiled the existence of two production subregions within Dehua: Gaide and Longxun-Sanban (Figure 3; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Yang, Chen, Cui, Dussubieux and Wang2021). Although the two subregions produced some similar items, such as covered boxes and plates, their products can be clearly differentiated by their unique elemental signatures. The identification of these subregions provides refined criteria for accurately tracing the origins of Dehua wares along maritime trade routes, potentially enhancing our understanding of historical production and trade dynamics.

Materials and methods

Materials

Our study implemented a purposive sampling strategy (Drennan Reference Drennan2010) to select Dehua-style ceramics from the Nanhai I shipwreck, aiming to capture a wide range of ceramic types and inscriptions for a comprehensive assessment of the compositional diversity of Dehua wares. Rather than quantifying the precise proportions of each type, our focus was on exploring the range of compositional variations, as cataloguing of the entire assemblage is still underway. These selected pieces come from all 14 compartments and broadly represent the variety of ceramic types and inscriptions present in the ship. A total of 172 Dehua-style pieces was selected, covering seven distinct forms—bottles, bowls, boxes, dishes, ewers, jars and plates—and 26 unique subtypes (Figure 4; Table 1). Of these pieces, 92 had ink inscriptions, while 31 were illegible, with a total of 19 different inscriptions identified (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Examples of analysed Dehua-style porcelains from the Nanhai I shipwreck (figure by Wenpeng Xu & Zhitao Chen).

Table 1. Classification and count of sampled Dehua-style porcelain, categorised by forms and subtypes, from the Nanhai I shipwreck.

Figure 5. Examples of Dehua porcelains bearing ink inscriptions from the Nanhai I shipwreck (figure by Wenpeng Xu & Zhitao Chen).

Our reference dataset, designed to establish a robust compositional reference framework, comprises 686 artefacts from 19 kiln sites at Dehua (Figure 3). This dataset incorporates compositional data from 565 samples (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Yang, Chen, Cui, Dussubieux and Wang2021), alongside information from an additional 121 samples from the recently excavated Weilin kiln in Sanban town (Yu Reference Yu2021). The inclusion of samples from this recent excavation not only augments our reference group but also helps cross-verify and validate the data collected at different intervals.

Methods

All samples used in this research were analysed using a Thermo Niton XL3t 950 GOLDD+ portable x-ray fluorescence spectrometer. Although this model was employed consistently across all samples, two separate devices were utilised: one for previously published reference samples (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Yang, Chen, Cui, Dussubieux and Wang2021) and the other for samples procured from the Nanhai I shipwreck and Weilin kiln (Yu Reference Yu2021). The configuration and procedural guidelines for analysis were maintained throughout the study. The primary filter of the spectrometer operated at 40kV and 100μA, and acquisition periods were systematically set to 120 seconds using the Test All Geo in the soils and minerals mode. To achieve a more comprehensive representation of the overall composition, readings were gathered from two different spots on each sherd. During the analysis, we monitored the readings for any variations or outliers, and excluded elements that had readings consistently below the limit of detection of the pXRF analyser. As a result, 13 elements were retained for this study—silicon, aluminium, iron, potassium, calcium, zirconium, manganese, rubidium, niobium, bismuth, lead, strontium and thallium.

While two pXRF devices of the same model and settings should theoretically yield comparable measurements, research on this topic remains sparse. To ensure comparability between the two devices, readings were calibrated by reanalysing 40 randomly selected samples from Dehua kiln sites with both devices and applying linear regression to adjust the readings from the first device to match those from the second. This analysis revealed a clear linear correlation between the concentrations of most of the examined elements measured by both pXRF devices; however, the correlation was less evident for silicon and aluminium, so these were excluded from further analysis.

To identify compositional patterns within our dataset, we employ multivariate statistical methods including Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Random Forest (RF). Developed by Breiman (Reference Breiman2001), RF is a powerful ensemble tree-based learning algorithm for classification and regression (Qi et al. Reference Qi, Zhang, Tang and Li2018). Here, we use RF to estimate the probability of an artefact being sourced from the Gaide or Longxun-Sanban subregions and to cross-validate these findings with the PCA results. To reduce disparities among major, minor and trace elements, log base-10 transformations were applied to the elemental values (Bishop & Neff Reference Bishop, Neff and Allen1989; Glascock Reference Glascock and Neff1992; Baxter Reference Baxter2006). All the analyses conducted in this study were performed using R, version 4.3.0 (R Core Team 2024).

Results and discussion

Determining the micro-provenance of Dehua-style porcelain

PCA results reveal a nuanced pattern regarding the micro-provenance of Dehua-style porcelains from the Nanhai I shipwreck (Figure 6). Most of the analysed samples closely match the compositional signatures of either the Gaide or Longxun-Sanban subregions, suggesting that a substantial portion of the Dehua-style porcelain onboard the Nanhai I shipwreck likely originated from Dehua.

Figure 6. PCA biplot illustrating the relationships between Dehua kiln samples (grey points) and Nanhai I shipwreck samples (coloured shapes), grouped and shaped by porcelain subtype. The ellipses demarcate the 90% confidence intervals for the Gaide and Longxun-Sanban subregions, highlighting the alignment of specific Nanhai I samples with these areas (figure by Wenpeng Xu).

An RF model, trained on a kiln dataset of 686 samples and using 11 pXRF-measured elements as predictors, was developed to predict the micro-provenance of qingbai porcelains from the Nanhai I shipwreck. Evaluated through a repeated 10-fold cross-validation strategy (James et al. Reference James, Witten, Hastie and Tibshirani2013), the model demonstrates a predictive accuracy of approximately 99.88% and a Kappa statistic of 99.71%, showcasing its effectiveness in accurately classifying the samples between the two subregions. The RF results, closely aligned with the PCA findings, yield insightful correlations between porcelain types and their origins within the Gaide and Longxun-Sanban subregions (Figure 7; Table 2).

Figure 7. Results of Random Forest analysis for the Nanhai I shipwreck samples, illustrating the probability of each sample's association with the Gaide or Longxun-Sanban subregions. The values plotted along the y-axis quantify the probability distribution between these two principal production subregions. A value of 0 indicates 100% probability of association with Gaide, while a value of 1 indicates 100% probability of association with Longxun-Sanban. Each point represents a sample, with differing colours and shapes corresponding to distinct porcelain subtypes (figure by Wenpeng Xu).

Table 2. Correspondence between porcelain subtypes from the Nanhai I shipwreck and their provenance within the Gaide and Longxun-Sanban subregions.

The Gaide subregion is identified as the origin for a specific set of porcelain subtypes, including bowl A, boxes A, B and E, ewer A, jar Bb and plates A–D. A wider variety of subtypes, including bottles A–C, bowl B, boxes A–D, the dish, ewers B and C, jars A, Ba, Cb and D and plate A, is attributed to the Longxun-Sanban subregion. Among these, certain subtypes (bowl A, box E, ewer A, jar Bb and plates B–D) are exclusively attributed to Gaide, while bottles A–C, bowl B, box C, ewers B and C and jars A, Cb and D are unique to Longxun-Sanban. Only a small number of ceramic subtypes, including boxes A and B and plate A, originate from both subregions, highlighting that most subtypes were uniquely produced in either Gaide or Longxun-Sanban. Additionally, our analysis reveals that some samples, primarily from bottle D, box F and jar A, Ba and Ca subtypes, could not be definitively linked to either Gaide or Longxun-Sanban. This misalignment suggests the possibility of additional, perhaps lesser-known, kiln sites other than Dehua contributing to the qingbai porcelain cargo of the Nanhai I shipwreck.

Micro-provenance analysis of Dehua-style wares with ink inscriptions

Porcelains bearing ink inscriptions were also analysed to determine their micro-provenance. As shown in the PCA biplot (Figure 8), there is a strong correlation between specific inscriptions and their corresponding production locales, with most inscriptions uniquely linked to a single subregion. Specifically, porcelains inscribed with surnames including 蔡 (Cai), 陳上名 (Chen Shang Ming), 戴 (Dai), 戴直 (Dai Zhi), 方直 (Fang Zhi), 黄直 (Huang Zhi), 林社 (Lin She), 楊直 (Yang Zhi), 王 (Wang) and 鄭知客記 (Zheng Zhi Ke Ji) are predominantly traced to the Gaide subregion. Conversely, those bearing marks including 東山 (Dong Shan), 谢直 (Xie Zhi), 郑 (Zheng), 莊德直 (Zhuang De Zhi), 王五 (Wang Wu) and 王十五卜記 (Wang Shi Wu Bu Ji) are linked to the Longxun-Sanban subregion. Among the analysed samples, only the inscription 莊直 (Zhuang Zhi) was associated with both subregions, appearing on the plate A subtype traced to Gaide and the box B and jar Cb subtypes linked to Longxun-Sanban.

Figure 8. PCA biplot illustrating the relationships between Dehua kiln samples (grey points) and Nanhai I shipwreck samples (coloured shapes), grouped and shaped by ink inscriptions. The ellipses demarcate the 90% confidence intervals for the Gaide and Longxun-Sanban subregions, highlighting the alignment of specific Nanhai I samples with these areas (figure by Wenpeng Xu).

Implications of micro-provenance findings

The micro-provenance analysis of Dehua-style porcelains from the Nanhai I shipwreck provides a nuanced understanding of porcelain production and maritime trade dynamics during the twelfth–thirteenth centuries. Most analysed Dehua-style samples of a given subtype can be traced back to a specific subregion; for example, the plate B–D subtypes are all from Gaide, and the bottle A–C subtypes are all from Longxun-Sanban, with only certain porcelain subtypes such as boxes A and B and plate A being sourced from both subregions. This pattern may arise if merchants preferred the products from a specific subregion despite both producing similar types of porcelain. However, it more likely reflects a differentiated production or competitive strategy within Dehua porcelain industry, wherein each subregion specialised in certain types of products rather than producing entirely homogeneous items for maritime trade. This is somewhat supported by archaeological evidence from the kiln sites, which shows distinct production traditions in the two subregions (Xu Reference Xu2021; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Yang, Chen, Cui, Dussubieux and Wang2021).

The examination of ink inscriptions further provides insights into the trading practices associated with Dehua kilns in the context of maritime commerce. A substantial number of Dehua porcelains with identical ink inscriptions can be traced back to the same subregion. As the cargo of Nanhai I is believed to have been owned by multiple merchants—a practice described in ‘Pingzhou Ketan’, which states, “商人分占贮货, 人得数尺许, 下以贮物, 夜卧其上” (Merchants occupied sections for storing goods, with each person allocated a small space. Goods were stored below, and at night, people slept above them; Zhu Reference Zhu2007: 133)—these ink marks are thought to denote ownership and facilitate the differentiation of goods among various merchants (Huang Reference Huang2007; Lin Reference Lin2018; Chen Reference Chen2020). Such patterns, where porcelains attributed to a particular merchant or owner are strongly linked with certain Dehua subregions, indicate that merchants may have preferred ordering specific goods from one subregion rather than broadly sourcing from both, suggesting the possibility of established relationships with specific kiln sites or production subregions.

The findings necessitate a reassessment of the production chronology for Dehua ceramics during the Song dynasty. Previous research suggests that the lower stratum of the Wanpinglun kiln site in the Gaide subregion—which yields ceramics identical to those discovered in the Nanhai I shipwreck—dates back to the late Northern Song dynasty, around the late eleventh to early twelfth centuries (Fujian Museum 1990). However, the identification of Dehua-style porcelain from the post-AD 1183 Nanhai I shipwreck, traceable to the Gaide subregion, provides compelling evidence of Gaide's active involvement in maritime trade well into the mid-Southern Song period or the late twelfth century. This suggests that porcelain production in Gaide either commenced later than previously assumed or persisted for a more extended period. Furthermore, these results raise questions about Dehua porcelain production and trading patterns in the twelfth century, especially when comparing the Nanhai I shipwreck to contemporaneous shipwrecks such as the Huaguang Reef I shipwreck (likely post-AD 1162) and the Java Sea shipwreck (latter half of the twelfth century), both of which carried similar cargo (Mathers & Flecker Reference Mathers and Flecker1997; Niziolek et al. Reference Niziolek, Feinman, Kimura, Respess and Zhang2018; National Center for Archaeology et al. 2022). Despite the significant similarities in the porcelain assemblages of these three shipwrecks (Meng Reference Meng2018), the Dehua-style qingbai plates (plates A–D) prominent in the Nanhai I shipwreck are conspicuously absent from both the Huaguang Reef I and the Java Sea shipwrecks. Given that the two shipwrecks are thought to pre-date the Nanhai I shipwreck (Meng Reference Meng2018), and that previous research suggests that the Gaide subregion at Dehua—renowned for its plates—may have started production earlier than Longxun-Sanban (Meng Reference Meng2017; Xu Reference Xu2021), this discrepancy leads to several compelling inquiries. Could the presence of plates in the Nanhai I shipwreck reflect a chronological shift in production patterns at Dehua, initially focusing on bottles and boxes before expanding to include plates by the late twelfth century? Might production in the Gaide subregion have begun even later than that of Longxun-Sanban? Alternatively, could this discrepancy be attributed to differing trading routes, merchant preferences or specific customer demands? A detailed micro-provenance analysis of Dehua-style porcelain from the Huaguang Reef I and Java Sea shipwrecks could further shed light on these complex production and trade dynamics.

Conclusion

Through detailed analysis of the micro-provenance of Dehua-style qingbai porcelains from the Nanhai I shipwreck, our research underscores the transformative potential of more fine-grained studies on traded ceramics. This research not only demonstrates the effectiveness of pXRF for high-precision micro-provenance analysis but, more importantly, provides a nuanced understanding of the intricate dynamics of porcelain production, maritime trade and associated trading practices that cannot be observed from traditional macro-provenance analyses.

The research successfully traces various types of Dehua-style porcelains from the Nanhai I shipwreck to the specific subregions. Most analysed samples of a given type originated from either Gaide or Longxun-Sanban, possibly indicating differentiated production or a competitive strategy. The examination of ink inscriptions on the ceramics further suggests that these Dehua porcelains likely belonged to different merchants or owners, who may have had preferred sourcing strategies or established relationships with particular kilns or production subregions. Additionally, the identification of certain Dehua-style items possibly not originating from Dehua suggests that the shipwreck may include products from lesser-known kilns. Moreover, by tracing the Dehua-style porcelains to a more precise provenance, this research challenges our understanding of the production timeline at Dehua; with both the Gaide and Longxun-Sanban subregions actively involved in porcelain production and maritime trade until at least AD 1183, the Gaide kilns might have started later or lasted longer than previously believed.

This study not only sheds light on the specific historical context of the Nanhai I shipwreck but, by illustrating the complex interactions and trade networks of the late twelfth century, our findings contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of global maritime connectivity and the economic and cultural exchanges that shaped the pre-modern world. This research highlights the broader utility of micro-provenance studies and the necessity of conducting similar analyses on other shipwrecks to further illuminate the intricate web of historical maritime trade.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the General Project of the National Social Science Fund of China (project number: 24BKG020).