INTRODUCTION

The settlement at Kastro/Palaia (Volos) is situated on the coast of the north bay of the Pagasetic Gulf. The site has been densely populated from prehistoric times until the present day, and is almost totally covered by modern buildings. In 1956, D. Theocharis (Reference Theocharis1956a; Reference Theocharis1956b) started systematic excavations on the west slope of the hill in Kastro/Palaia (Fig. 1), revealing, in his Trench III, impressive architectural remains that he ascribed to two successive palaces. Unfortunately, only short preliminary reports presented these important findings, and final publication was never accomplished. Late Bronze Age pottery was studied in the 1990s by Anthi Batziou in the framework of her PhD (Batziou-Efstathiou Reference Batziou-Efstathiou1998), but this study was hindered by the lack of comprehensive documentation from the old excavation. More recently, a program of restudy of finds from Theocharis’ excavation with limited reinvestigations in his Trench III has been carried out (Skafida et al. Reference Skafida, Karnava, Georgiou, Agnousiotis, Karouzou, Kalogianni, Asderaki, Vaxevanopoulos, Georgiou, Topa, Dionisiou, Tsoumousli, Margaritof and Mazarakis Ainian2020, with further bibliography). In addition to these investigations, several rescue excavations were carried out at various plots on Kastro/Palaia by local archaeologists. Twenty meters to the east of Trench III, an interesting excavation was conducted in 1988 by Z. Malakasioti (Reference Malakasioti1988; Reference Malakasioti1989; see also Batziou-Efstathiou Reference Batziou-Efstathiou1998) at A. Kokotsika plot (Velissariou street 38; Fig. 1), in a trench measuring 4 x 3.5 m. It provided important insights into the diachronic picture of the site, and in particular into the Late Helladic (LH) IIIC Early period that constitutes the topic of this article.

Fig. 1. General plan of Kastro/Palaia in Volos with locations of Theocharis’ Trench III and Kokotsika plot excavations. Based on Theocharis Reference Theocharis1956a, fig. 44 and Skafida et al. Reference Skafida, Karnava, Agnousiotis and Georgiou2018a, fig. 55.

EXCAVATION AND CONTEXT

The following account is based on the excavation notebooks kept at the Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia. In total, nine habitation levels were distinguished. The upper levels, numbered 9–7, excavated at a depth of 1.25–4.93 m,Footnote 1 are dated to the Byzantine, Archaic, Geometric, Protogeometric and LH IIIC Late periods. The remains of the LH IIIC Early and Middle phases are scarce in general, mostly restricted to successive floors, sometimes cut by refuse pits, with accumulations containing pottery and artefacts (Batziou-Efstathiou Reference Batziou-Efstathiou1998, 253–62). Level 6, at a depth of 4.93–6.05 m, is dated to LH IIIC Middle. Level 5, excavated from a depth of 6.05 to 6.35 m, with its uppermost part dated to LH IIIC Early, is the most interesting in terms of its pottery assemblage, deriving from a well-stratified context. This fact was the reason for the re-examination and study of the material of this particular level. Architectural remains containing a mix of decorated Mycenaean, local painted pottery in Middle Helladic tradition, unpainted and usually hand-made and burnished open shapes characterise the three levels numbered 4–2, from a depth of 6.35 to 7.10 m. They date to the Palatial and the Pre-palatial Mycenaean periods. Level 1 at a depth of 7.10 to 7.34 m features architectural remains and yielded purely Middle Bronze Age pottery.

Level 5 (depth 6.05–6.35 m; Fig. 2)

Starting from the depth of 6.05 m, the soil was mixed with clay and many charcoals. In the middle of the trench, there was an intensively burned area measuring approximately 0.80 x 0.60 m. This level produced abundant pottery and some small finds: a steatite conulus BE 6717,Footnote 2 bronze slag and some highly corroded unidentified metal finds, as well as part of a glass bead BE 6719.

Fig. 2. Photograph showing level 5 during excavation. Arrow pointing to approximate N. Author: Z. Malakasioti. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

In the north-east corner of the trench (Fig. 3), at a depth of 6.15 m, the excavator reports part of a hearth made of three successive layers of clay: the lower layer was of clay and contained pieces of charcoal and ashes, the middle layer of clay was thin, red, highly burned, and, above them, the third clay layer was likewise thin, with sherds of Handmade Burnished Ware on it, visible in Fig. 3. Around this hearth, bits of bronze slag, pottery and small finds were gathered. Among the small finds there were some unidentified heavily corroded bronze objects, part of an ivory object with holes BE 6734, two bone pins BE 6712, 6715, part of a Mycenaean figurine BE 6713, and a bronze ring BE 6714. A cavity with a diameter of 0.135 m and 0.20 m deep, plastered with clay only in its upper 0.14 m, was found in the middle of the hearth.Footnote 3

Fig. 3. Photograph showing detail of the hearth with sherds on top and a post hole, seen from SW. Author: Z. Malakasioti. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

The stone foundation of a wall (preserved length 1.65 m, width 0.50 m), constructed with big schist slabs, was found in the south of the trench, 0.75 m from the west and 1.95 m from the east baulk. According to the excavator, a large number of stones found in the layers above might have belonged to this destroyed wall. It is not visible in the photograph (Fig. 2), probably because it had already been removed when the photo was taken, but some stones can be seen sticking out from the southern baulk that might have belonged to it. There might be yet another wall visible in the south-west corner with three stones in the same north–south alignment.

Part of the foundation of a second wall (preserved length 1.32 m, width 0.54 m) with north–south orientation was uncovered in the north part of the trench (Fig. 2). The excavator considered it possible that this wall was connected with the other destroyed wall mentioned above.

Abundant pottery that came from bags labelled with depths of 6.05 and 6.15 represents a chronologically coherent assemblage, with numerous joins between various bags. It dates to the LH IIIC Early period, and constitutes the main topic of this article. Hereafter it will be referred to as ‘the deposit’.

At a depth from 6.15 to 6.27/6.35 m, a thick destruction layer (as described by the excavator) covered the trench with two successive layers of mud bricks mixed with pieces of plaster and of green pebbles, and below them, burned clay with much charcoal and ash. The pottery was much less abundant in this level, and only two small finds were registered: a Psi-type figurine BE 6881, and an obsidian blade BE 6682. Beneath it, a white plaster floor was revealed at a depth of 6.27 to 6.35 m, which was better preserved in the south and west part of the trench. It is readily visible in the excavation photo (Fig. 2). This plaster floor might have been repaired with green pebbles preserved towards the east side of the trench.

In the south-west corner of the trench, a structure formed with stones and clay was interpreted as a possible hearth. In the middle of it, another cavity with a diameter of 0.20 m and depth of 0.16 m was found. As visible in the excavation photo (Fig. 2), this cavity is made in the plaster floor, and therefore the entire structure may be related to the use period of this floor.

Only a limited amount of material was associated with this plaster floor, or in general with the levels below the LH IIIC Early deposit. It consisted predominantly of unpainted open shapes, such as shallow cups and kylikes, as well as conical cups with string-cut bases. The few decorated sherds were no later than the LH IIIA2 period and included a linear kylix base and a linear body sherd from a rhyton.

Stratigraphic levels below the depth of 6.35 m, i.e. below the level of the plaster floor, confirm this early date, as the latest decorated material does not post-date LH IIIA.

Refuse pit

In the north part of the trench, between the wall and the hearth, a circular refuse pit (diameter of 1.20 m) was identified at a depth between 6.27 and 7.72 m, cutting through earlier levels. As it cut through the white plaster floor (Fig. 2), and includes chronologically mixed material with latest fragments dating to LH IIIC Middle–Late, it represents significantly later activity.Footnote 4 The pit was filled with ash, charcoal, burned clay, pottery, as well as small finds such as a millstone BE 6680, two clay spools BE 6707, 6723, part of an anthropomorphic figurine BE 6708, part of an animal figurine BE 6722, shells of Patella caerulea that had been collected without the mollusc and were beach-worn (examined by R. Veropoulidou), as well as other species constituting unambiguous food remains.

Although the pit was first recognised at a depth of 6.27 m, according to the pottery found inside it must also post-date the activity attested with the LH IIIC Early level starting at 6.05 m. In the excavation photo (Fig. 2) a pile of stones is visible above the pit, reaching high above the plaster floor and the hearth uncovered at 6.15 m. These stones could therefore have formed part of the original pit fill, perhaps placed there to seal its mouth.

The proximity of the two excavations, Kokotsika plot and Theocharis’ Trench III (Fig. 1), and the stratigraphy of the Kokotsika plot with a white plaster floor at roughly the same depth as two white plaster floors revealed in Trench III (Skafida et al. Reference Skafida, Karnava, Georgiou and Agnousiotis2018b, 73, drawing 1) could suggest that they may be related, and perhaps belong to the same large Mycenaean complex. Theocharis considered these plaster floors as belonging to two consecutive palaces, one of the fourteenth century BC, the other of the thirteenth century BC, destroyed by fire early in the twelfth century BC. According to the pottery found below and above the plaster floor in the Kokotsika plot excavations, it could be linked to the earlier of the two floors found by Theocharis. The use of plaster floors could be a key element that distinguishes and differentiates the buildings where they were found from any other structures excavated so far in Kastro/Palaia dating to the palatial period (Batziou Reference Batziouin print).

PRESENTATION OF POTTERY

Introduction

The deposit from Kokotsika plot at Kastro/Palaia (Volos) presented here can be confidently placed in the LH IIIC Early period. On the one hand, it contains pieces that are not present in the LH IIIB2 Thessalian assemblages, like the painted carinated cup or linear deep bowl; on the other it lacks typical diagnostics of the ensuing LH IIIC Middle period known from Kastro/Palaia or Velestino, such as trays, large pictorial kraters, or reserved bands on the interiors of deep bowls. More precise synchronization with published deposits from Thessaly and other regions of Central and Southern Greece will be offered below.

In terms of deposit type, the Kokotsika plot cannot be considered a floor deposit. This is strongly suggested by the fact that among the mendable pottery there are no examples that would be close to a complete preservation. In fact, only one vessel (cup KP No. 38) has more than 50 per cent of its rim preserved, but even this piece does not preserve more than half of the entire vessel.Footnote 5 In addition, there are three vessels that preserve more than 40 per cent of the rim, and another three with more than 30 per cent of the rim preserved. This shows that we are dealing predominantly with parts of vessels, plus numerous single sherds. As the excavated area is not insubstantial, the lack of the remaining parts of better-preserved vessels cannot be explained as a result of a partial recovery of a larger floor deposit. Also, although the material presented here derives from rescue excavations, even small and undecorated sherds were kept. It is therefore likely that we are dealing here with a fill or dump. Whether the material originally accumulated in this location (and is thus in situ) or was redeposited from elsewhere (i.e. is in a secondary position), for instance in an attempt to raise the level, cannot be answered with the evidence at hand.

In total, 168 rim fragments (after mending) were counted, of which 14 were considered earlier than the core of the deposit, and one was identified as a later intrusion. As the non-contemporary material comes in the form of single sherds, its share in the assemblage is lower than what the simple rim count would suggest. Earlier pottery accounts for only 5 per cent of the entire assemblage, and so the material can be considered as chronologically quite homogenous.

Preservation

The pottery has on average a fair degree of preservation, but some variability is apparent, and consistent with the suggestion that it is not a floor deposit. Apart from the wear resulting from use (see below), many sherds display a medium degree of wear of their surfaces and edges, possibly to be explained as a result of exposure to moderate weathering. Nevertheless, some pieces have fresh sharp edges showing that they were not exposed for too long. Regarding the mendability rate, among 154 rim fragments, 25 were mended from two or more fragments. The average rim preservation is 7.5 per cent. The only other deposit for which comparable statistics are available is an LH IIIA1 pit from Kontopigado, and there this index is somewhat higher and amounts to 9.6 per cent (Kaza-Papageorgiou and Kardamaki Reference Kaza-Papageorgiou and Kardamaki2018, 7, table 1). The difference seems to result from a different type of context, as pits usually favour higher mendability.

Quantification method

In terms of pottery quantification, the decision was made to employ a method based on estimated vessels equivalents (EVE) for rims. The method involves measuring the percentage of the original circumference that a particular fragment preserves. It is usually done with a simple diameter chart that is divided into sections representing 10 or 5 per cent of the entire circumference. For this reason, it is only applicable to rims and bases, and not for features like handles or legs. The use of this method is not widespread in publications of prehistoric pottery in the Aegean,Footnote 6 yet according to a classic textbook by Orton, Tyers and Vince (1993, 171) ‘the vessel-equivalent is the only measure that is unbiased, both for measuring proportions within an assemblage and for comparing them between the assemblages’. Besides these unquestionable advantages, which are not common to other counting systems used in the field (feature and sherd counts, minimum number of individuals [MNI]), the other aspect of this method whose benefits are particularly clear is that it differentiates between vessels that are well preserved, irrespective of whether broken up into many pieces or complete, and single sherds. In the case of some other quantitative approaches (notably MNI), both a complete vessel and a single rim sherd would be counted as one. Here we have decided to restrict ourselves to rims only and exclude bases, as they are subject to the problem of ‘chunky types’ (i.e. they break into relatively few pieces) that is most acute in smaller assemblages (Orton, Tyers and Vince Reference Orton, Tyers and Vince1993, 174).

Recording procedure

A modification of a system that splits the pottery according to fabrics (fine; medium-coarse; coarse) towards one that reflects functional differences – or pottery classes (Rutter Reference Rutter1995; Hale Reference Hale2016) – was applied here. Following the standard approach, fine pottery, comprising mostly tableware, was subdivided into patterned, linear, monochrome and unpainted. Cooking pottery represents basically the only unburnished medium-coarse pottery in the deposit. Medium and large closed shapes used for short-term storage that could form another category in the medium-coarse fraction, in the case of coastal Thessaly are best described as medium fine rather than medium coarse. Therefore they were treated together with the rest of the fine pottery. The storage category consists of thick-walled pithoi with considerable amounts of non-plastic inclusions, that would usually – but not invariably – fall into the coarse fraction. Two additional classes were differentiated. One is Handmade Burnished Ware (HBW), comprising medium-coarse dark-fired fabrics with burnished surfaces. It must be stressed that despite its crude appearance, it rarely falls into the coarse category as traditionally defined, i.e. containing inclusions exceeding 4 mm in size (see below). The other class is Grey Ware, which belongs to fine pottery, and is distinguished by the grey clay colour of both surface and fracture, and burnished to polished surfaces. It can be differentiated from optically very similar Middle Helladic Grey Minyan mostly by way of its different morphological range. Grey Minyan was seemingly absent in this deposit, except perhaps in the form of small body sherds not readily assignable to a specific shape. However, due to the counting method employed, which considers only rims, this issue is eliminated.

Inventorying strategy and illustrations

In the inventorying process, preference was given to mendable material, as this has the highest odds of belonging to the core deposit representing a chronologically more coherent group than single sherds that may be coming from, for instance, disintegrated mudbricks. Indeed, all identified earlier fragments were single sherds with the exception of two bases – one of which was clearly reworked and repurposed (KP No. 29), while the other one could have also served as a stopper (KP No. 28) – and two stirrup jars (KP Nos 30–31; see the discussion below).

In accordance with this strategy, almost all mendable fragments were inventoried. Exceptions were body fragments lacking patterned decoration, as well as two lower body fragments of deep bowls consisting of several fragments, but with few actual joins among them. The inventoried material thus provides a good overview of the entire deposit that is supplemented by frequencies based on all rim sherds. Due to the importance of HBW and Grey Ware, in the case of these two classes also single fragments were inventoried. With regard to motifs, non-inventoried material is mentioned in the discussions of specific shapes.

The majority of inventoried pottery is illustrated with drawings and colour photographs. The remainder, consisting of a few undecorated or linear-painted fragments, are shown with photographs. In Figs 4–5, 7–11, 13 and 15–21, line drawings are shown alongside colour photographs of the same fragments in the same scale. Care was taken to correctly stance the fragments while taking photographs; in those rare cases when this was not possible, the photographed pieces may appear slightly bigger than on the drawings.

Fig. 4. Decorated deep bowls. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Fig. 5. Decorated deep bowls. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

The majority of non-inventoried fragments mentioned in the discussion are illustrated with photographs in Figs 6, 12 and 14.

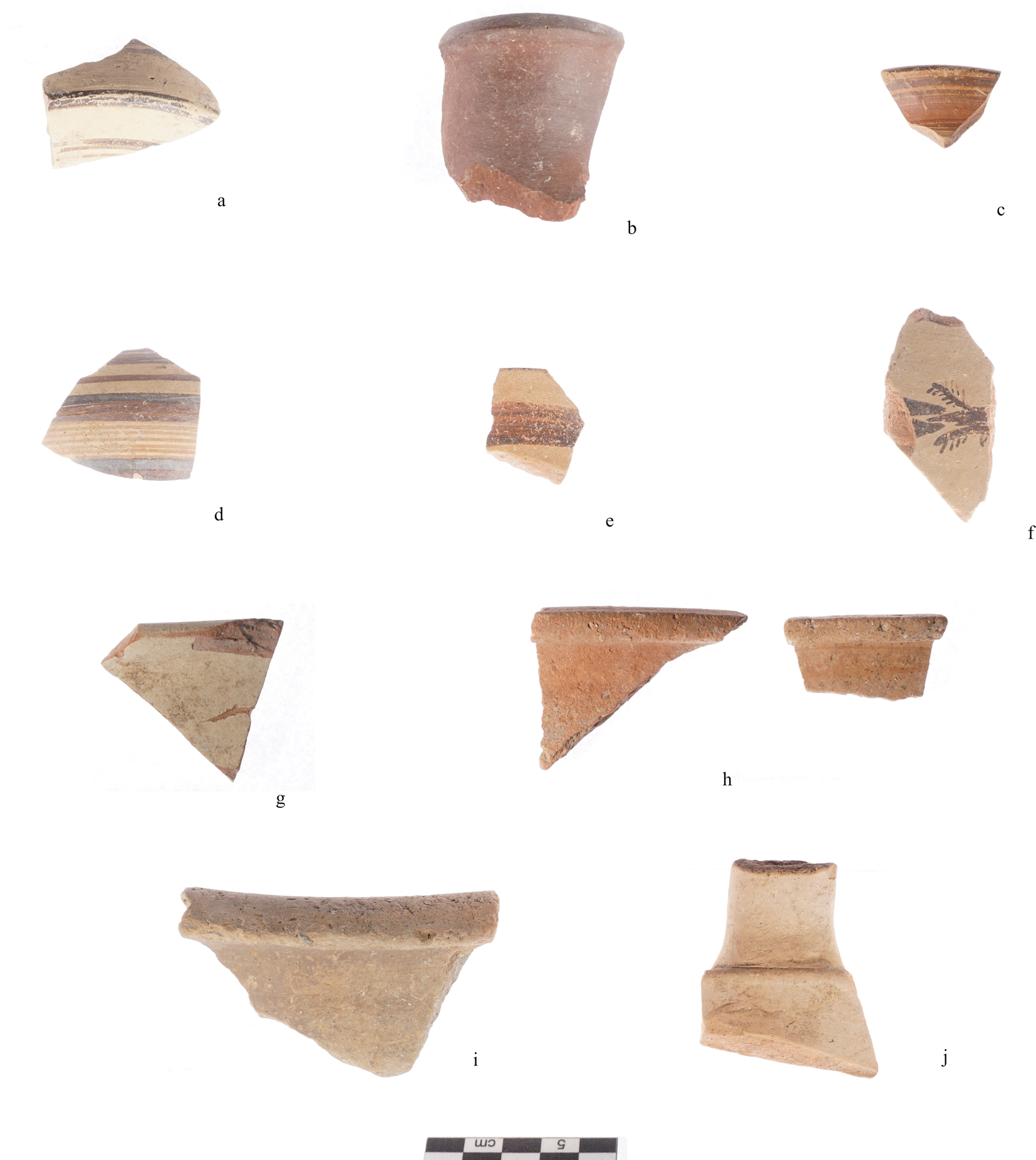

Fig. 6. Photographs of non-inventoried open shapes mentioned in the text. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Contrary to the common practice in pottery studies in the Aegean, no Munsell readings were taken on inventoried pottery. We hope that the rich photographic documentation taken in the same, neutral light conditions will compensate for this unorthodox approach. We believe that for the purposes of comparison (both within the presented assemblage and between pottery from various sites), colour photographs provide a much more useful basis.

Catalogue

Abbreviated catalogues for inventoried pottery and small finds are provided as tables in the online-only Supplementary Material (Tables A1 and A2). For pottery, they list both Furumark Shape (FS, when precisely identifiable) and Furumark Motif (FM, when applicable), which are omitted in the discussion below, as well as the number of fragments and rim and base diameters.

Frequencies of functional classes

Regarding the general composition (Table 1), the deposit represents a rather typical domestic assemblage of LH IIIC Early period, with one major exception being the extremely high share of Handmade Burnished Ware. Among the fine pottery, the painted fraction outnumbers the unpainted pottery by 2:1 (Table 2), but the unpainted variety is more prominent among the open shapes (40% vs 32%; Table 3). Such a relationship is most characteristic for quantified LH IIIC Early deposits, and dramatically different to what had been the case for the previous LH IIIB period, when the shares of the two broad categories were reversed (Thomas Reference Thomas2005, 459, table 2). Open shapes dominate the entire fine fraction, as well as its painted and unpainted subgroups, in each case representing more than 70 per cent (Table 2). Within the painted pottery, the share of monochrome types is negligible for open shapes, but impressively high (>50%) among the closed vessels (Table 3). Linear and patterned decorative schemes have roughly equal shares among open shapes, but within the closed vessels the patterned variety is practically non-existent, being limited to two stirrup jars and one body sherd of a larger closed shape (Table 3). Grey Ware represents a particular subset of fine pottery, with a small share of 1.4 per cent (Table 1). There is no identifiable medium-coarse pottery other than cooking pots, which, with a share of less than 8 per cent (Table 1), make up a comparatively small part of the assemblage.Footnote 7 Among the published pottery groups that are chronologically close to the deposit presented here, only the LH IIIB2 Causeway deposit (layer C) from Mycenae has a similar share of cooking pottery (Wardle Reference Wardle1973). In the case of the deposit presented here, this is most likely directly related to the very high share of HBW, which amounts to 14 per cent (Table 1). The fact that the frequency of this particular group at the majority of other sites does not exceed 1 per cent shows clearly how striking the difference in this respect is. The possible reasons for such a high share will be outlined in the later part of this article; suffice it to say here that the fact that some of the HBW vessels might have been used for food preparation may account for a low percentage of cooking pottery in the Kokotsika plot deposit. Finally, large storage containers (pithoi) represent 3 per cent of the entire assemblage (Table 1).

Table 1. General percentages of various pottery groups based on rim EVE.

Table 2. Percentages of various groups within fine and fine painted pottery.

Table 3. Percentages of various decoration schemes among fine open and closed pottery.

These frequencies may not be representative of the entire site during the LH IIIC Early period, but one needs to await further publications of relevant deposits to verify this.

DETAILED PRESENTATION OF POTTERYFootnote 8

Fine painted pottery

Open shapes

Painted open shapes represent almost 33 per cent of the entire assemblage, and slightly more than 70 per cent of the entire painted fraction (Table 2).

Deep bowls

Deep bowl is by far the most common open shape, as is typical for most of the LH IIIB/C Early pottery assemblages. If all cases where there is uncertainty whether a rim belongs to a deep bowl or another open form (like a cup or a stemmed bowl) are counted as deep bowls, its share amounts to 62 per cent.

As is fairly typical for Thessaly already in the deposits considered as LH IIIB2, the majority of deep bowls in the Kokotsika plot deposit have a monochrome interior. Nevertheless, examples with linear interiors are present, including a well-preserved deep bowl KP No. 2 (Fig. 4). The interior banding usually consists of a thin rimband and a second band below, which can be quite thick, as on KP No. 7 (Fig. 4).

The exterior banding on the rim may consist of a band of various thickness, from a thin one typical of Group A deep bowls (KP No. 2), to a medium-thick band (KP No. 1, Fig. 4) typical for a deep bowl of ‘Group C’ as differentiated by Elina Kardamaki (Reference Kardamaki, Schallin and Tournavitou2015, 84) for Tiryns. At least in one case there is no rimband at all (KP No. 10, but probably also KP No. 6, Fig. 4). All other examples have a banding typical of stemmed bowls, with additional band below a thin rimband.

On the lower body, the decorative zone is bordered by a single or a double band. There is usually a band at the base, slightly above its resting surface. Handles are invariably tri-splashed.

The usual profile is relatively straight with a gently flaring lipless rim; only in the case of KP No. 10 (Fig. 4) is the rim more sharply outturned, or even everted as on KP No. 4. At least one inventoried piece considered here as a deep bowl has a thickened lip (KP No. 1, Fig. 4). The reasons for ascription of these pieces to deep bowls are the following: 1) the extreme rarity of stemmed bowls already in the LH IIIB2 deposits in Thessaly; 2) the appearance of such a deep bowl type at the transition from LH IIIB2 to LH IIIC Early all over the Mainland (Mountjoy Reference Mountjoy1997, 111, figs 8–10); and 3) parallels for shape and decoration among better-preserved examples from Dimini with a ring base (Adrymi-Sismani Reference Adrymi-Sismani2014, 468, LH IIIB2).

Rim diameters of deep bowls in this deposit range from 14 to 20 cm, with a single smaller example (12 cm).

In terms of decorative motifs, the most popular one is the triglyph, usually filled with a zigzag or a wavy band. The panels made by the triglyph are often filled with antithetic spirals, and rims or sherds with parts of such spirals are quite frequent (KP Nos 4 and 8, Fig. 5). KP No. 4 is an example with the central triglyph filled with bivalves while the spirals have a cross-hatched decoration.Footnote 9 A single narrow central triglyph with compressed semi-circles is found on KP No. 2 (Fig. 4), which has a linear interior. Deep bowls decorated with such a motif are not attested at Dimini, but several examples are known from Pefkakia.Footnote 10 An unusual diagonal triglyph filled with a wavy band decorates deep bowl KP No. 3 (Fig. 5).Footnote 11 Narrow triglyphs are attested on deep bowls KP Nos 6 and 12 (Figs 4–5). In the case of KP No. 6 the side triglyph close to the handle is filled with zigzag, in KP No. 12 with a wavy band.

Dense spirals are also used in a running version (KP No. 1, Fig. 4),Footnote 12 which can have a solid centre (KP No. 13, Fig. 5). An uncatalogued rim sherd (Fig. 6a) is probably decorated with a stemmed version of this motif.

Two inventoried fragments are decorated with a floating zigzag (KP Nos 5 and 10, Figs 7 and 4),Footnote 13 and this is the only narrow pattern attested in this deposit.

Fig. 7. Decorated deep bowls. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

An unusual decoration on the deep bowl is a vertical whorl shell (KP No. 9, Fig. 7), reaching way below the handle attachment. Both the motif and the decorative zone extending towards the base are characteristics of early deep bowls. However, deep bowls decorated with vertical whorl-shells are known from LH IIIB2 levels at Dimini (BE 36002; Adrymi-Sismani Reference Adrymi-Sismani2014, 349). The example from the Kokotsika plot is of high quality and has a monochrome interior.

At least one specimen appears to belong to a linear deep bowl (KP No. 14, Fig. 7), although its fragmentary preservation does not exclude the possibility of it bearing a sparse decoration, like a central narrow triglyph (cf. KP No. 2, Fig. 4). KP No. 15 (Fig. 7), restored as another linear deep bowl on the drawing, preserves only the handle part and most likely bore patterned decoration. A ring base with part of a lower wall (KP No. 16, Fig. 7) featuring monochrome interior and a single band at the base on the exterior also belongs to a deep bowl. Among the uncatalogued material, there are fragments of two other mendable deep bowls preserving a ring base and fragments of linear lower walls.

No examples of monochrome deep bowls have been identified. Such deep bowls are virtually unknown in the LH IIIC Early materials from Thessaly.Footnote 14

Among the uncatalogued sherd material, there are two rim fragments that most likely belong to deep bowl rims (rather than stemmed bowls) that are decorated with a thick wavy band (Fig. 6bc), a type quite widespread on the Mainland at the LH IIIB2/C Early transition (Vitale Reference Vitale2006) and common in Thessaly.Footnote 15 One of the rims is thickened, the other everted in a typical manner for deep bowls decorated in this manner found at Dimini or Pefkakia. Both have monochrome interiors and a band at the rim.

Cups

There are two linear cup fragments, both with a gently flaring lip and a diameter of 10 cm. They have monochrome interiors, and a narrow (KP No. 18, Fig. 8) to medium-wide (KP No. 17, Fig. 8) band on the exterior. KP No. 18 preserves parts of both attachments to a vertical handle. It also has a slight carination at the height of the lower handle attachment. The profile of KP No. 18 is not unlike that of a kylix, but with this decoration it is a remote possibility. Both cups are very similar in terms of their fabric.

Fig. 8. Decorated cups, stemmed bowls and shallow bowl. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

While linear cups described above are already popular in the deposits assigned to LH IIIB2 in Dimini (Adrymi-Sismani Reference Adrymi-Sismani2014, 398, 432–3, 458, 473–4), a monochrome carinated cup (KP No. 19, Fig. 8) is a type not attested among Mycenaean pottery even in the re-occupation deposits at that site dated to LH IIIC Early.Footnote 16 In fact, in Rutter's scheme of the relative chronology of that period, this is a marker of phase 2 (Rutter Reference Rutter and Davies1977), i.e. not of the earliest LH IIIC. KP No. 19 preserves rim and sharp carination, while a large rim diameter (18 cm) leaves little room for doubts regarding the shape, as an angular kylix would have a much smaller diameter.

Stemmed bowls

Some of the fragments classified as deep bowls feature rims that could be also considered as stemmed bowls, but KP No. 11 (Fig. 8) has several features that suggest it may be the only positively identifiable stemmed bowl in this deposit.Footnote 17 The walls are splaying, terminating in an everted rim, and the lowest preserved part is so narrow that a ring base seems very unlikely. It has a monochrome interior, and a stemmed bowl rim banding on the rim's exterior. Only a small part of the decorative zone with a panel of vertical lines filled with horizontal wavy lines and flanked by half-rosettes is preserved, framed by two bands below the horizontal handle.

Another fragment that belongs to a stemmed bowl is a linear stem preserving part of a domed base and a small part of an unpainted interior (KP No. 29, Fig. 8). Its fabric suggests it is an import, possibly Argive, and a date in LH IIIB would be most likely. Nevertheless, the stem has been clearly reworked by breaking off the entire lower bowl, possibly to convert it into a stopper. No other fragments of bases that could be ascribed to stemmed bowls were identified in this deposit.

Shallow bowl

KP No. 21 (Fig. 8) is a relatively large (rim diameter of 20 cm) linear bowl with thickened and flat-topped rim and horizontal handles attached just below it. It has monochrome interior and rim top, two narrow bands enclosed by wider ones below the handles, and another narrow band below.Footnote 18 It is distinguished by a highly micaceous fabric.

Basins

In terms of decoration, two variants are attested in this deposit – with a monochrome (KP No. 26, Fig. 9) and a linear interior (KP No. 27, Fig. 9). KP No. 26 preserves a protruding, flat-topped rim and parts of a horizontal handle with flattened oval section. The rim's upper surface is solidly painted, and there is a band just below the rim, continuing on the handle. The rim diameter is substantial (30 cm).

Fig. 9. Decorated basins, kylix and kylix/bowl/dipper. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

KP No. 27 is a very low broad ring base, 13 cm in diameter, with a single preserved band on both interior and exterior.Footnote 19

Among the uncatalogued material there is an example of a basin with a slightly thickened rim, painted on top, with otherwise no decoration on the body and only a band along the horizontal handle (Fig. 6d).

Kylix

There is one certain and another possible fragment that belongs to a decorated kylix. While the only decorated kylikes common on the Mainland during LH IIIC Early are of the conical type, and are usually linear, a survival of a standard rounded decorated kylix FS 258 beyond the LH IIIB1 period seems to be typical of Thessalian assemblages.Footnote 20 Such kylikes are present in the LH IIIB2 destruction layers in Dimini, as well as in the re-occupation phase dated to early LH IIIC (Adrymi-Sismani Reference Adrymi-Sismani2014, 531–3). They are, however, very rare in similarly dated deposits at Pefkakia.

In the Kokotsika plot deposit, there is one fragment of such a kylix (KP No. 22, Fig. 9), preserving part of the body decorated with a palm motif, and exhibiting a monochrome interior.Footnote 21 It is of very high quality, very similar in this respect to the deep bowl KP No. 1.

An enigmatic linear vessel (KP No. 20, Fig. 9) features a narrow lower body that appears to be coming down to a stem, a small diameter, as well as purely linear decoration, thus unlikely to qualify for a stemmed bowl. Therefore it is considered here as a possible kylix, but it could be a cup/bowlFootnote 22 or even a large dipper.Footnote 23 It is unusual in many respects. It has a vertical upper profile, unfortunately without a preserved rim. There are thin grooves on the uppermost preserved wall, perhaps near to the rim. It has an irregularly spaced banding on the exterior with three bands at mid body, and a thicker band at the lowest preserved body, which could have even been solidly painted. The interior is monochrome, and the walls are relatively thick. There is use-wear in form of vertical scratches on mid body, which is normally not seen on kylixes (see the discussion below).

Mug

A single linear rim (not inventoried) appears to come from a mug (Fig. 6e). It has a rimband, and a single band on lower preserved exterior.

Kraters

Kraters represent a very small part of the deposit according to rim EVEs (below 1%), but there are three inventoried examples with different decorative schemes, each consisting of more than a single piece.

KP No. 23 (Fig. 10) preserves a handle and body fragments belonging to a substantial, high-quality and hard-fired krater, partially burnt. The decoration consists of a tricurved arch, with additional fill of two slightly curved horizontal bands and a solid triangle. The decorative zone is framed by bands. The interior is monochrome, and the paint has a metallic sheen. The partially preserved handle is obliquely pierced.Footnote 24

Fig. 10. Decorated kraters. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Another krater (KP No. 24, Fig. 10) preserves only body fragments, but exhibits a linear interior. The exterior is decorated with two stemmed spirals, perhaps radiating from the same point.Footnote 25

The third krater (KP No. 25, Fig. 10) preserves a small part of an incurving rim capped by a thickened and sloping lip. Rim and interior are monochrome. One of the body sherds preserves a slight thickening, most likely to a horizontal handle. It appears to be decorated with curvilinear patterns, painted with either three equal thin bands or in a thin-thick-thin banding system.Footnote 26 One of the sherds preserves also a different, partially preserved motif consisting of a loop and additional bands.

Kalathos

A single base fragment with linear exterior decoration, including the underside, and unpainted interior, could belong to a kalathos (Fig. 6f).

Closed shapes

Closed shapes represent the minority of the fine painted fraction, with a share of 29 per cent (Table 2). Most prominent among them are the monochrome examples (Table 3).

Jug/amphora/hydria

Painted closed shapes of medium size in this deposit are limited, with a single exception, to vessels either solidly painted or with a monochrome, dark reddish-brown wash that appears to constitute a thinner layer that does not cover completely the underlying surface. While their fragments are quite common in the sherd material, it was only possible to identify joining fragments belonging to two bases that were mended.

KP No. 37 (Fig. 11) is a flat raised base with part of the lower body solidly painted including originally the entire base underside, now preserving only patches of paint. Due to its intense use, the edges and underside of the base are heavily worn, as is also part of the upper preserved body (see below for a discussion of use-wear patterns in this deposit).

Fig. 11. Decorated jars and stirrup jars. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

KP No. 36 (Fig. 11) is a simple base, only slightly convex, with a dark reddish-brown paint. The base is worn at its edges, with more intense wear at c. 20 per cent of the base circumference, extending onto the wall.

A number of rims (Fig. 12) belong to such closed shapes, most probably either jugs or amphoras, less likely hydrias, as there is limited evidence for horizontal handles. The rims are most often of squared profile, and when more rounded profile is encountered, it usually has a gentle carination in the front part of the rim. There are rare examples of simple flaring rims, and one with a thickened and down-sloping lip. Hollowing on the interior is very rare. Vertical handles belonging to these shapes, attached to the rim, feature oval sections.

Fig. 12. Photographs of non-inventoried monochrome painted/washed closed shapes. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

At Dimini, monochrome painted or washed closed shapes seem non-existent. On the contrary, such vessels appear to be a standard constituent of ceramic assemblages at Pefkakia during LH IIIB2–IIIC Early period, and most likely also earlier. We might be dealing here therefore with some micro-regional differences in pottery consumption practices.

Stirrup jars

Two stirrup jars were mended from several fragments. For one of them, KP No. 31 (Fig. 11), it was possible to generate a composite drawing, from the base to the lower shoulder. It has a globular shape and a raised hollowed base. It is decorated with two fine line groups enclosed by bands on both sides, and traces of most likely enclosed zigzag on the uppermost preserved body. The underside preserves four concentric circles. The fabric, and the quality of manufacture, suggest it is an import, most likely from the Argolid.Footnote 27

The other stirrup jar, KP No. 30 (Fig. 11), preserves part of a shoulder with the beginning of a vertical handle and the lowermost stump of a most likely hollowed false neck,Footnote 28 both solidly painted. Decoration consists of a fringed flower with an internally dotted stem,Footnote 29 and a fine line group below. Lower on the body there is a double thin line, a typical linear feature put on the bodies of the stirrup jars. The flat course of the shoulder combined with a gentle transition to the body suggests this might be an example of either FS 167, the conical-piriform type, or FS 182, the conical type.

Feeding bottle

A single basket-handle with a ladder pattern preserving a very small part of the rim (KP No. 34, Fig. 13) confirms the presence of a feeding bottle in this deposit. The fragment appears to be burnt.

Fig. 13. Various decorated closed shapes. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Alabastra

The deposit from the Kokotsika plot includes non-joining fragments of what are probably two distinct rounded alabastra (KP Nos 32a and 32b, Fig. 13). One of them is a base mended from several sherds and decorated with multiple circles of varying thickness. The other is a single handle and body fragment from a rounded alabastron decorated with a rock pattern. The body profile is quite steep, indicating a higher version of the form with parallels in Dimini and Pefkakia (Adrymi-Sismani Reference Adrymi-Sismani2014, 544, LH IIIC Early; Batziou-Efstathiou Reference Batziou-Efstathiou, Weilhartner and Ruppenstein2015, 60, fig. 20).

A single uncatalogued base sherd (Fig. 14a) belongs to a straight-sided alabastron. The preserved decoration is linear on the lower body, with spaced concentric circles on the underside of the base.

Fig. 14. Photographs of non-inventoried decorated closed shapes and unpainted open shapes mentioned in the text. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Miscellaneous closed shapes

A single neck and shoulder fragment from a closed shape was inventoried as KP No. 35 (Fig. 13), as it preserves patterned decoration. There is a slightly irregular horizontal (rather than a wavy) band at the neck, a band at neck-shoulder transition, and two dots and an additional element (vertical stripe) next to them. This is the only example of a patterned closed shape except for the two stirrup jars.

Four non-joining shoulder fragments (KP No. 32c, Fig. 13) attest to the presence of a small monochrome closed shape, probably a roughly globular juglet similar to several examples attested at Pefkakia in the latest occupation levels.

A small fragment of upper body mended from five fragments (KP No. 33, Fig. 13) belongs to a closed shape with linear decoration, possibly imported. The banding consists of two thin bands enclosed between two thicker ones. The paint has a high lustre, and the surface is polished, a treatment not attested among the other Mycenaean pottery from the deposit.

An enigmatic squared slightly irregular rim fragment (with a diameter of 5.5–6.0 cm, Fig. 14b), in a very dark reddish-brown fabric and covered with a wash of a very similar colour, may belong to a spout of a large transport stirrup jar. The fabric containing calcareous and quartz inclusions is not unlike that of vessels considered to be of local manufacture (see below), but its colour and hard firing stands out.Footnote 30 Alternatively, this fragment could belong to an askos.

A single flaring rim (Fig. 14c) belongs to a small closed shape, either an amphoriskos or an alabastron, and has a band at the rim in and out. Its fabric does not correspond to local pottery. A shoulder body sherd with a beginning of a flaring monochrome neck should belong to another such shape. On the body it is decorated with an enclosed fine line group (Fig. 14d).

Another rim (Fig. 14e) could attest to the existence of a collar-necked jar, a shape that gains popularity on the Greek mainland from the beginning of the LH IIIC period onward (Mountjoy Reference Mountjoy1986, 134). It is a slightly flaring flattened rim, with a painted top, a band below on the exterior, and an unpainted interior.

Single body sherd from a closed shape, perhaps a collar-necked jar, is the only example of pictorial decoration in this deposit (Fig. 14f). It shows a fish attacking another animal.

Fine unpainted pottery

As mentioned above, such pottery is outnumbered by the painted fraction, since it represents less than 40 per cent of the entire fine fraction (Table 2). Again, open shapes have a much higher frequency than closed unpainted vessels (77.7 vs 22.3%, Table 2). Nevertheless, even among the open shapes the number of mendable vessels was small. The difficulty of finding joining pieces (especially body sherds) among unpainted sherds was definitely an important factor here.

Open shapes

There are several different types of open vessels attested in this deposit, but only a few are preserved with more than a single fragment.

Cup

A shallow cup with a slightly carinated profile, KP No. 38 (Fig. 15), is the most completely preserved vessel in the entire deposit, but is still missing more than 50 per cent of its body. It has a flat, only slightly raised and string-cut base, rounded carination and a flaring lipless rim. The vertical handle has an oval section

Fig. 15. Unpainted open shapes. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Kylikes

Two mended fragments, KP Nos 41 and 42 (Fig. 15), preserve most likely lower bodies of kylikes. Their profiles are conical, but nothing can be said about the upper bowl and rim. Both are made of a pale yellowish fine fabric.

Several kylix rims preserved as single fragments have earlier profiles, suggesting an LH IIIA2–B1 date.

Interestingly, there is not a single fragment that could be confidently ascribed to a conical kylix, a popular type at both Pefkakia (Batziou-Efstathiou Reference Batziou-Efstathiou, Weilhartner and Ruppenstein2015, 67, fig. 44) and Dimini (Adrymi-Sismani Reference Adrymi-Sismani2014, 549), as well as in Theocharis’ excavations at Kastro/Palaia (Theocharis Reference Theocharis1956b, 126, fig. 43β).

Kraters

Unpainted kraters are attested only in sherd material. Several rim types are present. A fragment with a distinct pale slip over a dark red clay body preserves an everted rim with a tapering lip (Fig. 14g). This could belong to a stemmed krater of a type attested in Dimini both in LH IIIB2 and LH IIIC Early levels (Adrymi-Sismani Reference Adrymi-Sismani2014, 370–1, 555–6, nos BE 35819 and 35637). Another similar rim preserves the stump of a vertical strap handle.

Ring-based kraters are attested by two squared rims (Fig. 14h), one of them exhibiting a convex upper surface. There is also a thickened rim with a convex top, slightly undercut, and another protruding rim with a convex top in a medium-fine fabric (Fig. 14i).

Basin

Just as was true of kraters, unpainted basins are attested only in sherd material. Again, there is quite a variety in rim types, including a thickened and protruding rim, and a protruding flat-topped rim with pale slip, preserving the stump of a horizontal handle. There is also a thickened down-sloping rim to a shallow example of this shape.

Mug

The presence of an unpainted mug is attested by several pieces from rim to base of a small example (KP No. 43, Fig. 15).Footnote 31 The base is slightly convex, and the rim is flaring, exhibiting traces of use-wear (see below). The handle is not preserved.

Deep bowl

Relatively deep body and a flaring lipless rim of KP No. 40 (Fig. 15) most likely belongs to an unpainted deep bowl. In the sherd material, there is also a complete horizontal handle possibly to another unpainted deep bowl. Such deep bowls are generally rare, but seem to be more common in early LH IIIC layers at other sites such as Iria in the Argolid (Döhl Reference Döhl and Jantzen1973, 170–1, nos A6, A9, A11, A12, pls 69–70).

Dipper

An uncatalogued thick-walled rim with a high-swung handle must belong to a relatively large dipper (Fig. 14j). Among the unpainted rims there might be others that belong to that shape.

Shallow angular bowl

A single mended fragment (KP No. 39, Fig. 15) belongs most likely to a shallow angular bowl. It preserves a slightly hollowed base and parts of the lower bowl, and is very well made. Interestingly, among the sherd material there is only one rim with a carinated profile, more likely part of a kylix, and not a single example of a rim with a horizontal handle that would unequivocally attest to the presence of this vessel type in the deposit.

Closed shapes

The only closed shape preserving a significant portion of its profile is a medium-sized jar with a sharply flaring rim (KP No. 44, 17 cm in diameter; Fig. 15). Based on the profile, and slight wear at the rim, it could be identified as a dipper jug. This shape is best known from Lefkandi (see Evely Reference Evely2006, 19, 52, figs. 2:5.2, 2:8.2, nos 66/P183 and 66/P308), but has been also attested in Pefkakia.

Uncatalogued rims include a squared, triangular rim, slightly undercut with a thickening indicating the presence of a vertical handle, another rim with a rounded profile, and two non-joining fragments preserving a tall, slightly flaring neck ending in a flattened rim that is only slightly thickened

Grey Ware

Grey Ware is a rare category in this deposit (1.4% of the total pottery, Table 1), but one of significant importance for the stratum's overall interpretation due to its association with Handmade Burnished Ware (see the discussion below). It appears to consists of two shapes only – a carinated cup and a closed shape. The fabric is grey in colour, sometimes exhibiting a thin core that can be slightly lighter or darker than the rest of the fracture. Surfaces are burnished, sometimes reaching a stage of polishing when single burnishing troughs are no longer discernible. The undersides of the bases also receive this labour-intensive surface treatment. There are clear wheelmarks on most of the inventoried fragments. All examples of open shapes in Grey Ware are preserved as single sherds.

Carinated cup

The shape, as can be reconstructed from single fragments, has a flaring tapering lipless rim (KP No. 51, Fig. 16), relatively sharp carination (KP Nos 46, 47, 50, Fig. 16), and slightly convex lower body coming down to a ring base, that can be quite low (KP No. 52, Fig. 16) or more standard in profile (KP No. 49, Fig. 16). It is equipped with a vertical, probably high-swung strap handle (KP No. 48, Fig. 16). The inventoried handle significantly changes its course right above the attachment. Examples from Kastro/Palaia seem to belong to large cups, as rim KP No. 51 has a diameter of 21 cm and the diameter at the exterior carination of KP No. 47 is 19 cm.

Fig. 16. Grey Ware. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

At Dimini, carinated cups in Grey Ware come in two sizes.Footnote 32 Small cups have a diameter around 10 cm; large ones are twice as big (Adrymi-Sismani Reference Adrymi-Sismani2014, 559). They are characterised by ring bases, sharp carinations similar to that of KP No. 47, and flaring rims. The handles of large specimens are strap in section, although not as wide and thin as KP No. 48 (Adrymi-Sismani Reference Adrymi-Sismani2014, 559–60). Cups from Dimini for which parallels from Broglio di Trebisacce and Torre Mordillo have been quoted (Jung Reference Jung2006, 49–51) seem to closely match those from Kastro/Palaia.

Closed shape

A single closed shape in Grey Ware is represented by two joining raised and flat base fragments (KP No. 45, Fig. 16) belonging to a medium-sized wheelmade jar (base diameter 9.2 cm).

Closed shapes are a rare addition to the repertoire of Grey Ware pottery. From Dimini, only one closed shape has been published – a belly-handled amphora BE 35826 (Adrymi-Sismani Reference Adrymi-Sismani2014, 561), unfortunately without a preserved base.

Cooking pottery

Cooking pottery represents a surprisingly small part of the entire assemblage (less than 8%, Table 1). Nevertheless, its composition is highly interesting. Mendable cooking pots belong to a distinct class of Aeginetan-tradition cooking pottery. This class, thoroughly discussed elsewhere (Lis et al. Reference Lis, Kiriatzi, Rückl and Batziou2020), was most likely manufactured by potters representing a tradition developed on the island of Aegina that spread around 1200 BC towards the north, reaching as far as the Pagasetic Gulf. Nevertheless, according to the petrographic analysis only one of the cooking pots from this deposit appears to be local to the general area. Wheelmade cooking pottery that can be termed ‘Mycenaean’ is attested only with single sherds.

Aeginetan-tradition, handmade

The single best-preserved Aeginetan-tradition cooking pot (KP No. 53, Fig. 17) is a tripod, probably two-handled, with a short everted rim. Three other inventoried fragments preserve only everted rims (KP Nos 54, 56–57, Fig. 17), and it is uncertain if they represent other tripods or could possibly belong to flat-based jars. However, no flat bases have been identified in this group.Footnote 33

Fig. 17. Cooking pottery and pithos. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Wheelmade Mycenaean

Flat-based jars, in turn, are attested among the few fragments of wheelmade cooking pottery. The bases are raised and flat (KP No. 58, Fig. 17). Rims are very different from the Aeginetan-tradition cooking pots, as they are everted but very long, either slightly tapering (KP No. 62, Fig. 17) or flattened (KP No. 61, Fig. 17). Interestingly, KP No. 62 is similar to Aeginetan cooking pottery of the Early Mycenaean period. Being a single sherd, it could be an earlier kick-up.

Pithoi

The only significantly preserved example of a large storage container is KP No. 87 (Fig. 17), comprising four rim fragments joining into a substantial part of the circumference.Footnote 34 Interestingly, some, but not all, of these fragments are clearly burnt. The rim has a distinctive profile, protruding on both interior and exterior and featuring a flat top. Surfaces are wiped, but not very regularly. There is a shallow irregular groove just under the rim on the exterior. The vessel is handmade.

An uncatalogued protruding and flat-topped rim belongs to a larger closed shape, perhaps another pithos.

Handmade Burnished Ware

There are two reasons for which we are confident identifying this handmade pottery as Handmade Burnished Ware of Italian type. First, there are specific shapes, like the carinated cup, for which exact typological equivalents can be found only among the Late Bronze Age sites of the Italian peninsula. Secondly, preliminary petrographic analysisFootnote 35 of a selection of HBW pottery from this deposit indicates frequent use of grog, i.e. crashed pottery, in paste preparation process, a feature very characteristic for impasto pottery in Italy (Levi Reference Levi1999; Cannavò and Levi Reference Cannavò and Levi2018; Levi, Cannavò and Brunelli Reference Levi, Cannavò and Brunelli2019) as well as for some of the Handmade Burnished Ware found in the Aegean (Whitbread Reference Whitbread and Motyka Sanders1992; D'Agata, Boileau and De Angelis Reference D'Agata, Boileau and De Angelis2012) and beyond (Boileau et al. Reference Boileau, Badre, Capet, Jung and Mommsen2010; Pilides and Boileau Reference Pilides, Boileau, Karageorghis and Kouka2011).

There are a few observations that can be made here that regard other aspects of technology. Irrespective of the colour of the surface, which varies from light brown to black, the breaks are invariably very dark to black, indicating most likely a short firing process that did not allow for a complete oxidation of the organic matter contained in the clay. Most, but not all, fragments of HBW have burnished surfaces. The quality of burnishing varies, from cursory to extremely careful, providing an almost decorative effect on the neck of a closed shape KP No. 83 with vertical burnishing strokes. An interesting detail of the burnishing process was revealed after a close-up inspection of the marks. In the majority of cases, and irrespective of the quality of the final effect, burnishing troughs have an interior texture consisting of very fine parallel striations. This would indicate that the surface was treated not with a smooth object, like a rounded pebble or piece of bone, as is usually assumed, but with an object that had some sort of texture.Footnote 36 In terms of decoration, a few shapes exhibit impressed decoration.

From an overview of the existing literature, one may get the impression that HBW is made of coarse fabrics. However, close inspection of fabrics in this deposit, combined with petrographic examination, reveals that while some of the pieces exhibit a high density of inclusions, these inclusions rarely exceed 2 mm in their maximum dimension. Therefore, they should more accurately be classified as medium-coarse, even in the case of the most thick-walled fragments. In comparison with Mycenaean cooking pottery, the fired fabrics of most HBW pieces are in fact less coarse.

In terms of vase-building technique, material from the Kokotsika plot does not reveal much beyond the mere fact that these pieces are handmade. There is only a slight indication of coil joins in few of the studied fragments. Interestingly, a cup with a vertical rim handle (KP No. 68) appears to have a lower handle attachment plugged through the wall.

According to the statistics based on rim EVEs, HBW constitutes an extraordinarily high percentage of the entire deposit, amounting to 14 per cent (Table 1). The assemblage is dominated by closed shapes, in a reversed proportion to that attested for the Mycenaean pottery.

Carinated open shapes

The carinated cup (or bowl) is probably the most distinct type of Handmade Burnished Ware pottery. Its presence in the Kokotsika plot deposit is attested by several fragments, but the type does not seem to be very frequent. The clearest example is KP No. 64 (Fig. 18) preserving a sharp carination at the junction of the lower and upper wall, the latter with a very straight, almost vertical course, flaring out only close to the rim.Footnote 37 It exhibits high quality burnishing with vertical strokes.

Fig. 18. Handmade Burnished Ware – various open shapes. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Handle and body fragments, initially inventoried together as KP No. 63 based on the presence of decoration, turned out to belong to two different vessels following a detailed macroscopic fabric analysis. Body fragment KP No. 63b (Fig. 18) belongs to a cup with a rounded transition between upper and lower wall and preserves a scar to a probably vertical handle. Upper wall and the rounded transition are decorated with impressed oblique lines arranged most likely in opposing groups.Footnote 38 Burnishing is of particularly high quality on the exterior.

Fragment KP No. 63a (Fig. 18) belongs most likely to a complex handle with a horned apex. Preserved is part of a single horn sharply turning upwards and ending with a flattened, slightly convex top. It is decorated on one side only with impressed curved lines, forming some sort of a festoon pattern.Footnote 39

Other cups and bowls

Rim and handle fragment KP No. 65 (Fig. 18) derives from a large cup/bowl with a composite vertical handle of strap type that has a standard loop part attached to the rim and a vertical protrusion raising above the rim. Based on Italian parallels, there are numerous variants of how this part above the rim could be shaped (Damiani Reference Damiani2010, 272–369). The rim is entirely covered by the handle, and a possible carination is not preserved, hence this fragment is not discussed under carinated open shapes. This piece is distinguished by a grey surface, but neither the coarser fabric nor wall thickness nor lack of wheel traces allows it to be classified as Grey Ware. It features high quality burnishing, vertical along the handle and horizontal on the interior of the bowl.

KP No. 66 (Fig. 18) is a small flaring rim fragment to a cup, and is relatively thin-walled. It has horizontal burnishing of good quality.

Rim and handle fragment KP No. 84 (Fig. 18) belong probably to a cup with a high handle of strap type. The upper wall is almost vertical and ends in a simple rim. There is a protrusion on the lowest preserved exterior part of the sherd that could mark the lower handle attachment. Burnishing is traceable only on parts of the sherd, but this might be due to surface wear.

A very different type of an open shape is represented by KP No. 68 (Fig. 18). It is a cup with a complete vertical handle of almost circular section.Footnote 40 The handle's lower attachment is plugged through the wall, which is visible only in the break, but not on the interior surface. The precise profile of the rim is masked by the handle's attachment so that it is impossible to know if it was genuinely as simple as depicted in the drawing here. Likewise, it is uncertain whether there was an impressed plastic band at the height of the lower handle attachment. Finally, the stance of the wall could be more vertical than shown in the drawing. In that case, similarity to the cups of the type present at Lefkandi would be more obvious (Evely Reference Evely2006, 120, pl. 26:4, fig. 2:42; see also Jung Reference Jung2006, 200).

A bowl of substantial size (rim diameter 27 cm) with a flattened, slightly thickened rim is documented by two rim fragments (KP No. 74, Fig. 18). One of them preserves a triangular protrusion on the rim top.Footnote 41 The stance of the other fragment is uncertain, and if both belong to the same vessel, the lower wall must be more incurving. Good quality horizontal burnishing is preserved on all surfaces.

Large bowls

The largest of the HBW vessels from the Kokotsika plot deposit is a bowl, KP No. 67 (Fig. 19), with tapering body, slightly convex walls and a single preserved horizontal handle of an oval section situated at mid-body height. Its diameter can be estimated at c. 50 cm. It resembles somewhat BE 35997 from Dimini (Adrymi-Sismani Reference Adrymi-Sismani2014, 567), while a bowl with similar dimensions, yet with no handles, was found in Late Minoan IIIC levels at Chania (80-P 0235: Hallager and Hallager Reference Hallager and Hallager2000, 166, pls 51, 67d). Its walls are up to 1 cm thick. It shows mostly horizontal burnishing, both on exterior and interior.

Fig. 19. Handmade Burnished Ware – large bowl and closed shapes. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Jars with incurving rims (and plastic band)

Such jars are probably the most common type of HBW vessel found on the Greek mainlandFootnote 42 and represent a common type of impasto pottery in Italy referred to as olla (Damiani Reference Damiani2010, 267–72, pls 89–92).

The best preserved HBW vessel in this deposit (KP No. 70, Fig. 19) belongs to this characteristic type. It is a jar with an incurving rim and plastic finger-impressed band just below the rim. Almost 40 per cent of the rim is preserved. There is a single tongue-shaped lug protruding from the plastic band. The rim is only slightly flattened on top. On the interior, just below the rim, there are traces of added clay that were not entirely obscured by subsequent burnishing. The quality of surface treatment is good, and it seems that in this case it was executed in various directions with overlapping troughs resulting in a higher lustre.

Another similar form is KP No. 73 (Fig. 19). In this case the rim is more obviously flattened and additionally decorated with oblique incisions made with a sharp tool. What is unusual is that the interior does not show any traces of burnishing, while the exterior has only very cursory burnishing. There are clear finger impressions on the interior just below the rim, perhaps from an upward movement while building the vase.

KP No. 80 (Fig. 19) displays an almost vertical upper wall, with a flattened rim. Below the rim there is an elongated tongue-shaped lug, on one end of which there seems to be an edge of a finger impression, suggesting that it is a part of a plastic band, just as the one attested for KP No. 70. On the part of the interior the flattening of rim forms a slight protrusion. There are traces of high quality burnishing, but most of the surface is worn.

Possibly from a similar jar, but with an uncertain stance, comes a wall fragment, KP No. 75 (Fig. 19), featuring an elongated horizontal lug with a central finger impression. Good horizontal burnishing is preserved on the exterior, covering even the finger impression; the interior is most likely worn and preserves only faint traces of a similar treatment.

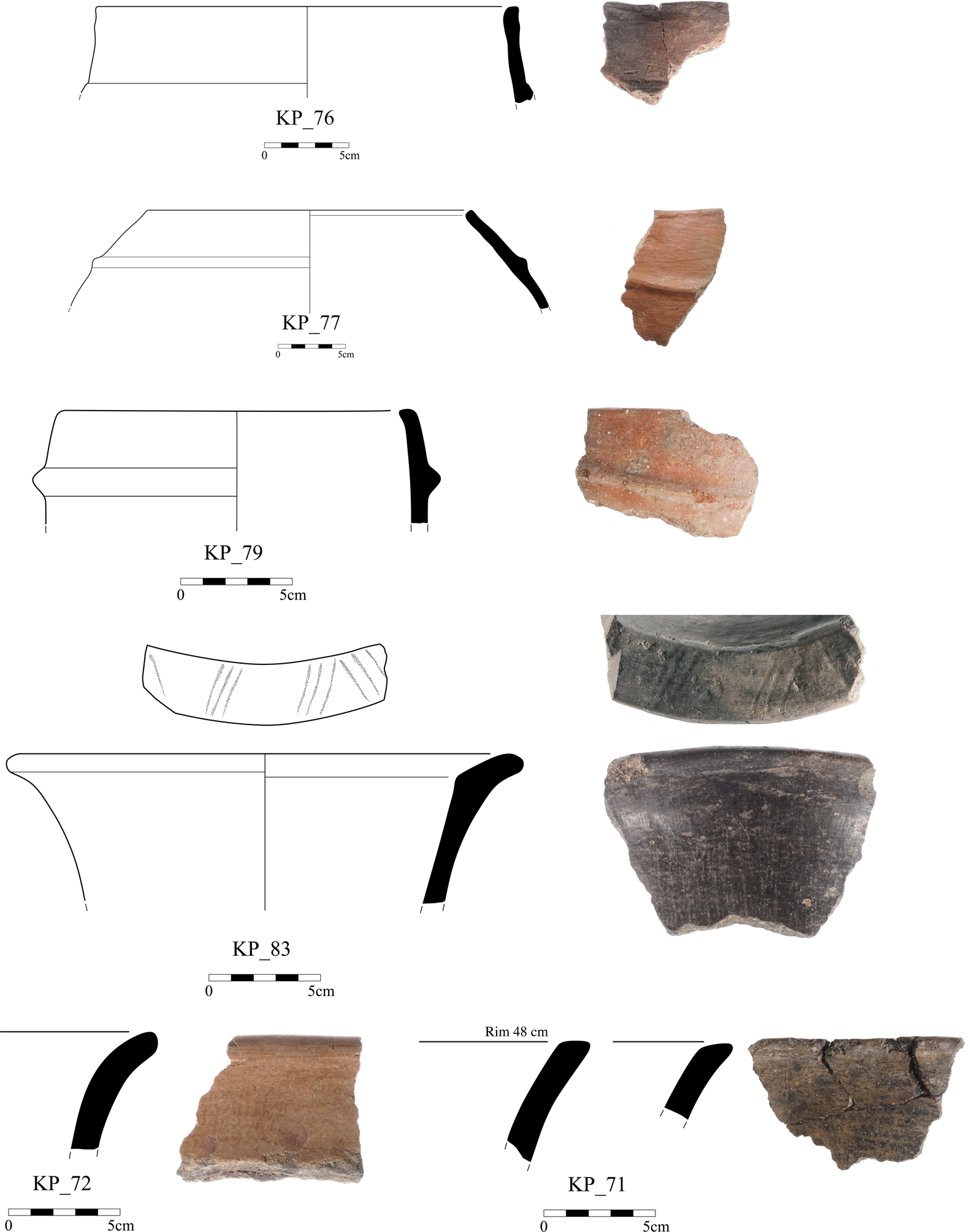

KP No. 76 (Fig. 20) is another, but again slightly different jar of the same general type. The upper wall is straight in its course, as opposed to a more usual curved wall typical for this shape, and curves slightly in. It ends with a partially flattened rim. Quite low below the rim, at the edge of the preserved sherd, there is the beginning of a plastic band, which may have been plain. It would be the only example of a plain plastic band in this deposit. Levels above it, with the majority of pottery dating to LH IIIC Middle, yielded two further incurving jar rims with plain plastic bands (KP Nos 77 and 79, Fig. 20, both from the depth of 5.70–5.95).Footnote 43 The surface of KP No. 76 does not preserve any traces of burnishing, and it does not seem that this is due to surface wear. The irregular interior surface in particular does not seem to have received any final surface treatment. The course of the plain plastic bands on both examples deriving from a later context is slightly oblique, but since these are small fragments of the entire vessel it is uncertain whether this is just an irregularity or a conscious choice of a potter.

Fig. 20. Handmade Burnished Ware – various closed shapes. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Other closed shapes

KP No. 83 (Fig. 20) is a single fragment preserving spreading neck ending with an everted rim. The flattened upper surface of the lip is decorated with groups of opposed diagonals, in a manner perhaps similar to the cup KP No. 63b.Footnote 44 There might be additional impressed dots between the diagonals, barely visible even in strongly raking light. In terms of manufacturing details, there is a slight overhang on the interior just below the rim which has not been obscured by later treatment. The burnishing is of excellent quality, approaching an almost decorative effect with vertical troughs on the exterior.

A similarly high quality of burnishing is present on KP No. 72 (Fig. 20), a very large jar with a simple flaring rim. Its surface is pale brown, but the core is very dark. Breaks preserve traces of coil joins, a rare feature for HBW from the Kokotsika plot.

A very large jar with a spreading neck and flattened but not everted rim is represented by KP No. 71 (Fig. 20). In general form it is similar to KP No. 83. It exhibits good quality burnishing, with troughs going in various directions on the exterior, being more regularly horizontal on the interior.

A much different closed shape with a vertical shoulder handle of round section is represented by KP No. 86 (Fig. 21). It has a globular shoulder turning into a neck, but only its beginning is preserved. The handle attachments are spaced very close to one another.Footnote 45 The walls are very thick, on average 1 cm. Burnishing is of a fairly good quality.

Fig. 21. Handmade Burnished Ware – various closed shapes. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Another jar, KP No. 82 (Fig. 21), has a flaring slightly tapering rim and a vertical handle of oval section. Its overall form is reminiscent of Mycenaean cooking pots, a phenomenon attested among examples of HBW from other sites (Kilian Reference Kilian2007, 23, pls 17–18).

There is a simple flat base with straight, spreading lower walls, inventoried as KP No. 85 (Fig. 21). It could belong to one of the closed shapes described here, but it cannot be excluded that it derives from larger open shapes, like KP No. 67. KP No. 85 is among the coarsest examples of HBW from the Kokotsika plot deposit and preserves traces of a fairly regular horizontal burnishing on the interior, but only cursory vertical burnishing on the generally irregular exterior surface.

KP No. 78 (Fig. 21) is another flat base, but the wall is more curved, and it probably belongs to a smaller closed shape, possibly a jar with an incurving rim. It exhibits vertical burnishing on the exterior, and horizontal on the interior. The base's underside is, once again, burnished.

Use-wear

Several vessels from the discussed deposit display various types of use-wear. Perhaps the most distinct pattern manifests itself through abraded scratched surfaces. Parts of vessels that display this use-wear include rims, bases and the most protruding parts of the body. It is present on deep bowls (their rims and convex lower bellies) KP Nos 2 (Fig. 22a), 3, bowl/kylix/dipper KP No. 20, mug KP No. 43, and two monochrome closed shapes, KP Nos 36 and 37 (Fig. 22b). In the latter case, the use-wear is present on the base and lower body. It is particularly noticeable on KP No. 37 since due to the wear some of the paint was also removed, revealing patches of exposed clay body.

Fig. 22. Examples of use-wear on pottery from the Kokotsika plot. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

This type of use-wear is well known from other sites, particularly Lefkandi (Lis Reference Lis2013), and seems to be most common during the LH IIIC Early period, thus in line with the date proposed for the Kokotsika deposit. It has been associated with the use of various vessels for scooping out content from other, coarser containers. In the case of closed shapes that could have served as water jars, such use-wear might have developed during the drawing of water from a well.Footnote 46

Another type of use-wear found on several open shapes occurs on the interiors of their rims in the form of worn paint. It is present on deep bowls KP Nos 10 and 15 (Fig. 22c), stemmed bowl KP No. 11 (Fig. 22d) and bowl KP No. 21. This could derive from stirring or removing of the contents with a spoon, which leaned against the interior rim during this action.

Deep bowl KP No. 16 (Fig. 22e) displays wear at the centre of the interior. The source of such wear could be similar to that described immediately above.

A closed shape in Grey Ware KP No. 45 (Fig. 22f) features use-wear on the resting surface, which is readily visible due to abrasion of the burnished surface. This is probably a result of moving of the vessel around.Footnote 47

Fabrics

During the recording of the material, basic macroscopic fabric analysis was conducted. Its results are summarised below. It should be noted that it was not possible to assign every fragment to a particular fabric group.

In terms of fine pottery, the most common fabric type appears to be orange-brown (sometimes yellowish-orange) in colour, with calcareous and dark red/brown rounded inclusions present in varying density, occasionally with pieces of shell. There is no or very little mica visible. Pottery of this fabric is usually pale-slipped. Among examples made in this fabric are deep bowls KP Nos 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 12,Footnote 48 and basins KP Nos 26 and 27. Krater KP No. 23, with a pinkish-brown fabric colour, could be considered as a finer variant of this fabric. Closed shapes, like KP Nos 35–37, feature a similar fabric but with the addition of quartz. The unpainted cup KP No. 38 seems to be manufactured in this fabric, even though it is of darker colour (dark red-brown).

This fabric is very common also at Pefkakia, throughout the LH III deposits, and with considerable likelihood it can be considered local to the area.

Perhaps a variant of the same fabric is characterised by yellowish-brown colour, a similar set of inclusions, but more consistent presence of mica on the surface. This fabric is characteristic for deep bowls KP Nos 1, 9, 10, 13, cups KP Nos 17–18, kylix/bowl KP No. 20, and krater KP No. 24. All of them are decorated with red paint. Among unpainted open shapes, this seems to be the prevalent fabric, represented by KP Nos 39–43.

Another characteristic but rare fabric is pale yellowish in colour (sometimes with a greenish hue), with very few visible inclusions, except for a few dark rounded ones. Deep bowl KP No. 15 and stirrup jar KP No. 30 were classified as its members.

Clearly distinct fabrics were noticed in the case of shallow bowl KP No. 21, with a highly micaceous fabric, stirrup jar KP No. 31 and alabastron KP No. 32b, characterised by a very fine yellowish fabric with pinkish hue. The latter two are considered imports from the Argolid.

Grey Ware pottery seems to have been made in a fabric featuring mostly calcareous inclusions, with a few dark rounded ones. The main difference between the fragments is the varying frequency of mica on the surface, ranging from none to quite frequent. Perhaps this reflects the basic distinction between the two main fabric groups described above. In that case, the fabric of Grey Ware could be considered as likely local.

In terms of coarser pottery, fabrics of cooking pottery were described elsewhere (Lis et al. Reference Lis, Kiriatzi, Rückl and Batziou2020), while the fabrics of Handmade Burnished Ware will be discussed together with the results of petrographic analysis in a forthcoming publication. The only inventoried pithos is made from a medium-coarse fabric with poorly sorted quartz, some dark rounded inclusions, at least a single schist fragment and mica (mostly gold) on the surface.

SMALL FINDS

A variety of small finds came from the discussed level (see Table A2 for a catalogue). There was a single female figurine of Psi type, preserving a lower body and stem with splaying hollowed base (BE 6713, Fig. 23). It is decorated with lines on front and back upper body, a waistband, and four vertical lines along the stem. BE 6717 (Fig. 23) is an intact black steatite conulus with a conical body and thickened upper end. There were two bone pins, BE 6715 and BE 6712, both of round section (Fig. 23). The first one preserves the upper part with a small hole at the end, the other one includes only the lower part ending in a sharp edge. There is one rectangular piece (strip) of ivory (BE 6734, Fig. 23), with partially preserved rectangular projection at one end. The other short end is broken. It is slightly curved. Its front surface is smooth, originally polished, with only occasionally traces of short saw cuts along the edges. The underside is flat, smooth, with oblique tool marks. On the left edge (as shown on Fig. 23), the smooth surface ends with a sloping ridge. One peg-hole is preserved, with possible traces of a second one at the broken end of the rectangular projection. The thickness of the piece decreases towards the bottom edge.Footnote 49 In terms of glass objects, there was a single fragment of a glass bead BE 6719. A number of small bronze objects in the form of a pin, a ring, and a spindle-shaped object, mostly highly corroded, were also recovered (BE 6710, 6711, 6714, 6714).

Fig. 23. Small finds. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Finally, a rounded disk made from a krater body sherd should be discussed under small finds (Fig. 23). It has only a roughly circular shape, and on one of the sides it preserves two partially drilled holes. It seems that for some reason the reworking of this sherd has not been accomplished. The original vessel was a krater with monochrome interior, decorated with an elaborate panelled pattern on the exterior.

DATE OF THE DEPOSIT

The LH IIIC Early date of the assemblage from the depth of 6.05–6.15 appears to be confirmed by a number of features. The most significant fragment in this respect is the monochrome carinated cup KP No. 19. Jeremy Rutter (Reference Rutter and Davies1977) saw its appearance as a diagnostic of his phase 2. None of the types that would suggest a later date, such as linear conical kylikes (Rutter's phase 3) or reserved bands on deep bowls (LH IIIC Middle, Rutter's phase 4), are present in this level. On the other hand, there is a significant number of links with LH IIIB2 and LH IIIC Early deposits at Dimini, and also LH IIIB2–IIIC Early levels at Pefkakia, as demonstrated by provided parallels, whereas none of the above features monochrome carinated cups. Also, the fabrics of Aeginetan-tradition cooking pottery from the Kokotsika plot exhibit no connection with fabrics of such pottery from Pefkakia (Lis et al. Reference Lis, Kiriatzi, Rückl and Batziou2020, 306), perhaps another indication of a chronological difference. An almost complete absence of unpainted carinated kylikes in the discussed deposit could be another such difference, as they seem to be popular both at Dimini (Adrymi-Sismani Reference Adrymi-Sismani2014, 546–8) and Pefkakia (Batziou-Efstathiou Reference Batziou-Efstathiou, Weilhartner and Ruppenstein2015, 67, fig. 43). Therefore, we would like to suggest that the Kokotsika deposit post-dates the abandonment of Dimini, while it may not represent the latest phase of LH IIIC Early in Thessaly.

It is important to note that the distinct regionalism of Thessalian pottery manifests itself also in this particular deposit. Notable are the absence of monochrome and extreme rarity of linear deep bowls, both types being common during early stages of LH IIIC in other areas of Central Greece. There is definitely more to learn about the LH IIIC period in Thessaly from a ceramic perspective, and additional deposits should be studied and published from the area.

Finally, we would like to note that some of the fragments found in the deposit presented here could pre-date the bulk of the pottery belonging to LH IIIC Early. Among such possible earlier pieces we could highlight both stirrup jars KP Nos 30 and 31, the patterned kylix KP No. 22, or the deep bowl with vertical whorl-shell KP No. 9. With the exception of the imported stirrup jars, these fragments could also be considered as examples of conservatism in the local pottery tradition.

POTTERY FROM LAYERS ABOVE AND BELOW THE DEPOSIT, AND THE PIT

Layers above the deposit