Public-opinion research seeks to understand the social forces that shape peoples’ beliefs, values, and identities, and education has long been one of the most used and most consistent predictors of social attitudes (Bobo and Licari Reference Bobo and Licari1989; Brooks Reference Brooks2006; Hyman and Wright Reference Hyman and Wright1979; Kingston et al. 2003; Page and Shapiro Reference Page and Shapiro1992; Schnabel and Sevell Reference Schnabel and Sevell2017; Selznick and Steinberg Reference Selznick and Steinberg1969; Smith Reference Smith1995; Stouffer Reference Stouffer1955; Weakliem Reference Weakliem2002; Weil Reference Weil1985). This study considers two key theories, development and socialization, that attempt to explain how education shapes social attitudes. I modify and test these competing theories on attitudes toward violence in the United States.

In the personal development model, education fundamentally changes people and their character so that they are more tolerant, more supportive of democratic values, and less authoritarian (e.g., Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Nevitt Sanford1950). In the traditional socialization model, education socializes students to the “official culture” of individualism, libertarianism, and antiauthoritarianism (e.g., Phelan et al. Reference Phelan, Link, Stueve and Moore1995). Yet, acceptance for state violence persists in the United States despite increasing levels of education that are thought to promote liberal values and antiauthoritarianism. Although some vocal opponents of police brutality have been highly educated people, we do not know whether the average college-educated American is more likely to oppose police violence than those with less education who are more likely to face the consequences of state-sanctioned violence (e.g., experience police brutality or fight in wars).

The apparent acquiescence of much of the American public to state violence motivates a test and possible refinement of previous theories. I set forth a refined socialization model, which builds on Jackman’s argument that education can promote dominant interests and legitimate injustice, at least in the United States (Jackman Reference Jackman1994; Jackman and Muha Reference Jackman and Muha1984). I argue that education does not have a uniform antiauthoritarian effect; instead, American education socializes students to establishment culture and interests that are both anti-welfare and pro-policing.

EDUCATION AND ATTITUDES

Although the education-as-development model for the relationship between education and attitudes was the traditional view held by foundational social psychologists and public-opinion researchers (e.g., Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Nevitt Sanford1950; Rokeach Reference Rokeach1960; Stouffer Reference Stouffer1955), key work has since found greater support for an education-as-socialization model (e.g., Phelan et al. Reference Phelan, Link, Stueve and Moore1995; Selznick and Steinberg Reference Selznick and Steinberg1969; Stubager Reference Stubager2008; Weil Reference Weil1985). For example, Phelan and colleagues (1995) leveraged a few distinct attitudes toward homelessness to show that—consistent with the socialization model—education is positively associated with tolerance and support for civil liberties for homeless peopleFootnote 1 but negatively associated with support for economic aid to them. Phelan et al. (Reference Phelan, Link, Stueve and Moore1995) argued that the “educational system is the primary vehicle through which the ‘official’ or ‘ideal’ culture is transmitted to citizens” (p. 130). According to them, the official culture of the United States emphasizes tolerance, individualism, and the myth of meritocracy.

The socialization model has proven effective, and Stubager (Reference Stubager2008; Reference Stubager2009; Reference Stubager2010; Reference Stubager2013) considered and confirmed it repeatedly in a Scandinavian context. In the process, he applied identity theory (see, e.g., Brenner, Serpe, and Stryker Reference Brenner, Serpe and Stryker2014; Stets and Serpe Reference Stets, Serpe, DeLamater and Ward2013; Stryker Reference Stryker2008; Tajfel Reference Tajfel and Tajfel1978) and introduced a new focus on socialization into not only “official culture” but also group identity and consciousness. According to Stubager, schooling produces an educated identity characterized by consistent libertarianism and antiauthoritarianism.

In a refinement and new application of the theory, I considered and tested whether education can socialize students into not only “official culture” and antiauthoritarian identity but also establishment identity, values, and interests.

In a refinement and new application of the theory, I considered and tested whether education can socialize students into not only “official culture” and antiauthoritarian identity but also establishment identity, values, and interests. In other words, I examined whether American education may be associated with preference for the educated ruling class on issues of both redistribution as Phelan and colleagues (1995) demonstrated and state-sanctioned violence that protects and extends the interests of the ruling class. Therefore, rather than the blanket anti-statism highlighted by Phelan et al. (Reference Phelan, Link, Stueve and Moore1995) and antiauthoritarianism highlighted by Stubager (Reference Stubager2008), I suggest that education may yield issue- and context-specific pro-statism in the interest of the purportedly meritocratic ruling class (Jackman Reference Jackman1994; Jackman and Muha Reference Jackman and Muha1984). A subsection of highly educated Americans has vocally opposed state-sanctioned violence, but what does the average college-educated American think about state-sanctioned violence (e.g., police brutality against racial minorities, war, and torture) that does not negatively affect people like them and which could be seen as upholding their interests? Support for—or at least complacency toward—state-sanctioned violence among the growing college-educated population in the United States could help explain why Americans have not put an end to ethically problematic state violence (e.g., police brutality or the torture carried out at Guantanamo Bay).

To apply this refinement of the socialization model, this study examined attitudes toward different types of violence—namely, interpersonal versus state-sanctioned violence. (On the importance of testing whether different related attitudes operate differently, see Gibson Reference Gibson2013.) Some factors, such as gender, are known to be consistent predictors of attitudes toward violence. As Smith (Reference Smith1984) showed, women are consistently more opposed to violence across surveys and types of violence. Education may demonstrate a similar pattern in keeping with the developmental model and previous socialization model or, consistent with my refinement of the socialization model, different patterns could emerge.

Developmental Model and Previous Socialization Model

Those with more education condemn violence by any group, including the state, because schooling promotes personal development of a consistent ethical frame (i.e., the developmental model) and promotes libertarianism while countering authoritarianism (i.e., the previous socialization model).

Proposed Socialization Model

Those with more education condemn interpersonal violence but accept some forms of state-sanctioned violence because schooling socializes people to establishment culture, identity, and interests, thereby legitimating ruling authority and its actions.

METHODS

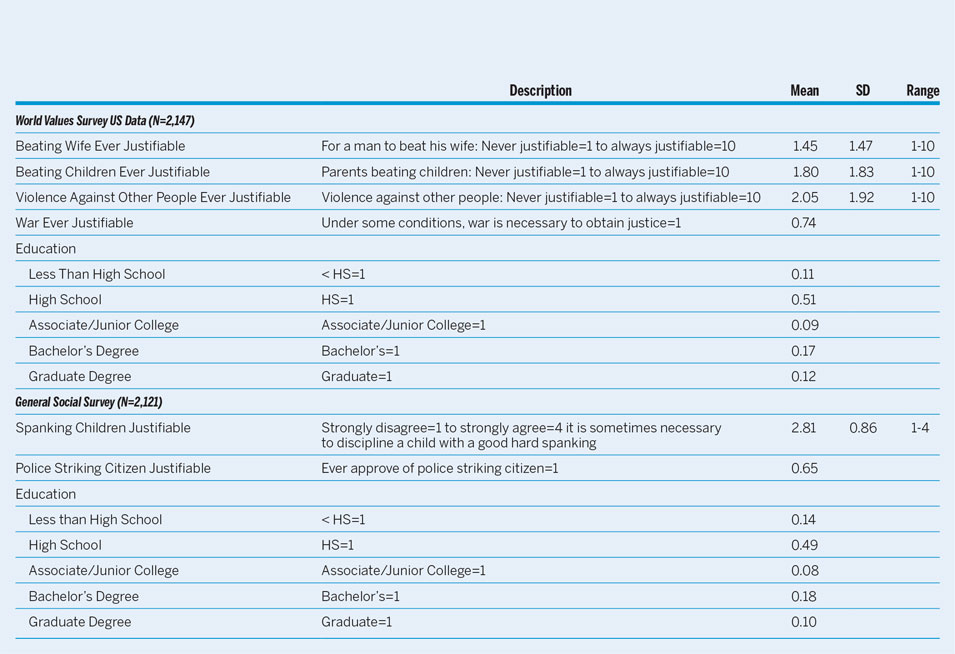

To adjudicate between these possibilities, this study used US data from the World Values Survey (WVS) and the General Social Survey (GSS). The WVS is a cross-national and nationally representative survey of basic values and beliefs. I used US data from the sixth wave (2010–2014) of the WVS, which provide information on education, key covariates, and attitudes toward interpersonal and state-sanctioned violence. The interpersonal-violence measures were preceded by the following directions: “Please tell me for each of the following actions whether you think it can always be justified, never be justified, or something in between.” The response options for these justifiability-of-violence measures—“for a man to beat his wife,” “parents beating children,” and “violence against other people”—ranged from 1 (“never justifiable”) to 10 (“always justifiable”). The justifiability-of-state-sanctioned-violence measure asked the following: “Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: Under some conditions, war is necessary to obtain justice.” Table 1 lists descriptive statistics.

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics for Key Measures

The GSS, a nationally representative survey of Americans, is one of the most widely used and trusted surveys in social-scientific research (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Marsden, Hout and Kim2015). I used cross-sectional data from the 2010, 2012, and 2014 surveys, which provided information on education, covariates that parallel the WVS data, and measures of interpersonal and state-sanctioned violence. The measure of interpersonal violence asked, “Do you strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree that it is sometimes necessary to discipline a child with a good, hard spanking?” The measure of state-sanctioned violence asked, “Are there any situations you can imagine in which you would approve of a policeman striking an adult male citizen?” The response options were yes and no.

Highest educational degree attained was the key predictor for both the WVS and GSS, and I included covariates drawn from previous research (e.g., Phelan et al. Reference Phelan, Link, Stueve and Moore1995) and available in comparable form in both the WVS and GSS. I present a series of models in which I continued to add relevant covariates that could account for any relationship between education and attitudes. I started with a bivariate model of the impact of education on attitudes, then added key sociodemographic characteristics, then measures of political views and party identification, then family income (measured as self-placement on a 10-point scale in the WVS and as total family income in the GSS), and finally mother’s and father’s education (which are only available in the GSS). These measures were added to consider whether education differences result from education itself or other factors, such as race and socioeconomic status (SES), which are highly correlated with education.

The samples were constrained to the cases for which each of the outcome measures and education were all available; missing data on covariates were handled with multiple imputation. I used binary logistic regression for the binary outcomes and ordinary least squares (OLS) for other outcomes. The patterns were not sensitive to the models used: sensitivity analyses with Alternating Least Squares Optimized Scaling (ALSOS; these results are included in the supplement),Footnote 2 ordinal logistic regression models, and multinomial logistic regression models yielded equivalent patterns.

This pattern of more highly educated people believing in the justifiability of state-sanctioned violence was consistent with a modified socialization model in which people learn to hold establishment values that legitimate state-sanctioned violence.

RESULTS

US World Values Survey Analyses

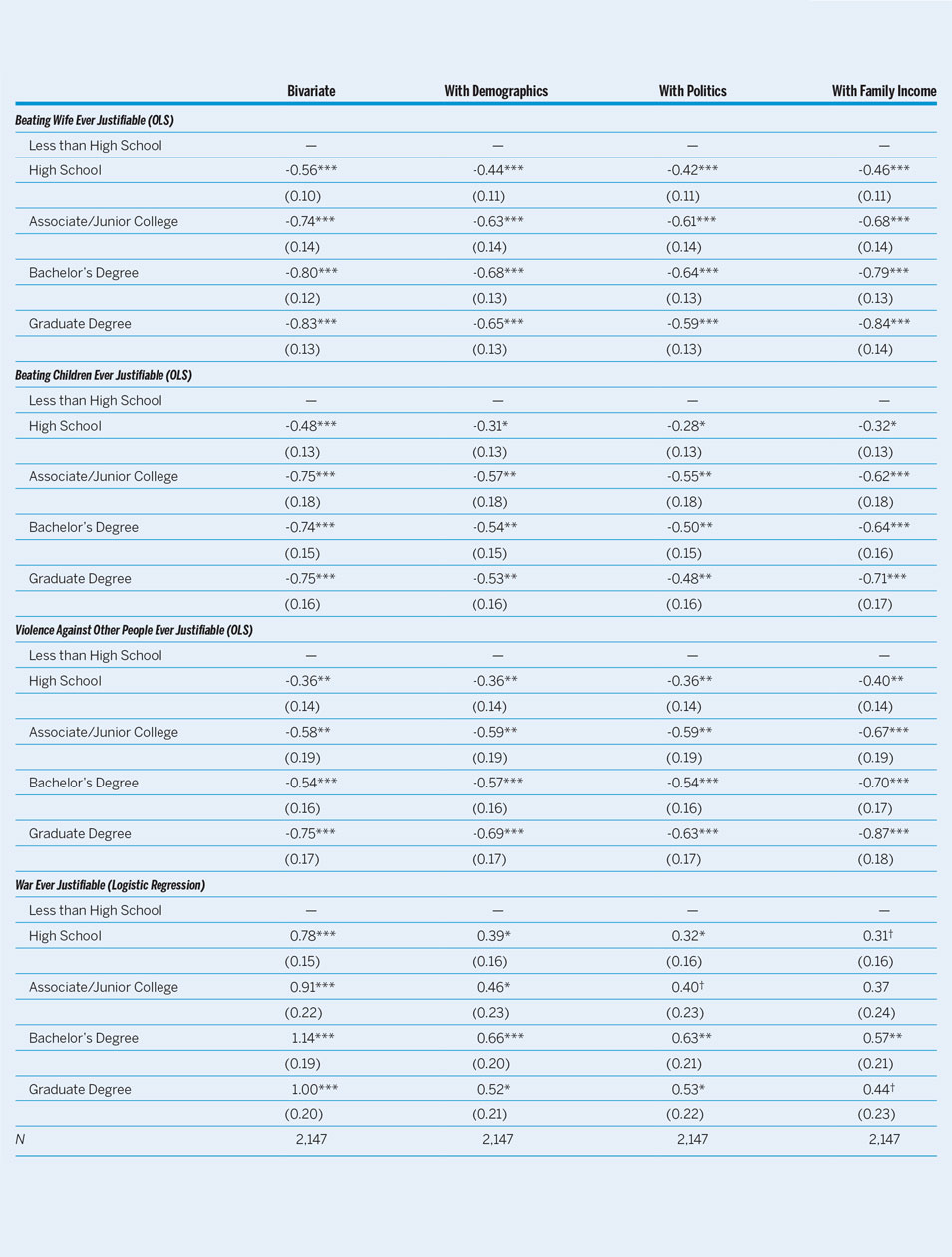

Table 2 shows US World Values Survey results on whether interpersonal and state-sanctioned violence can ever be justifiable. Americans with more education are less likely to think that intimate-partner violence, violence against children, and violence against other people can be justifiable.Footnote 3 However, education is positively associated with the belief that war is sometimes necessary. This pattern of more highly educated people believing in the justifiability of state-sanctioned violence is consistent with a modified socialization model in which people learn to hold establishment values that legitimate state-sanctioned violence.

Table 2 Education Predicting Justifiability of Violence, US World Values Survey

Source: World Values Survey, Wave 6 (2010–2014).

Standard errors are in parentheses.

Notes: Demographics model adds gender, race/ethnicity, age, region, marital status, and parental status. Politics adds political views and party identification (all previous covariates are retained when covariates are added to sequential models). Family income adds self-placement on a 10-point income scale.

† p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The patterns for covariates (not shown) were consistent with previous research. Women were less supportive of violence across measures. Being non-Latinx white had a similar impact to having more education: non-Latinx blacks, Latinxs, and people in the “other race” category were more likely than whites to say that interpersonal violence can be justified but less likely to believe in necessary war. These patterns suggest further support for a modified socialization model of attitudes in which establishment people (i.e., highly educated white men) espouse the establishment value of state-sanctioned violence being justifiable.

The general pattern for education persisted despite sometimes smaller coefficients as various covariates were added to the model. The most notable general attenuation of the impact of education was present in the model that added sociodemographic covariates, such as gender and race. Politics and family income did not account for the education pattern; in fact, the impact of education was generally similar to the bivariate pattern once family income (measured as self-placement on a subjective 10-point scale of incomes) was in the model. Therefore, the impact of education appears to be operating independent of SES.

US General Social Survey Analyses

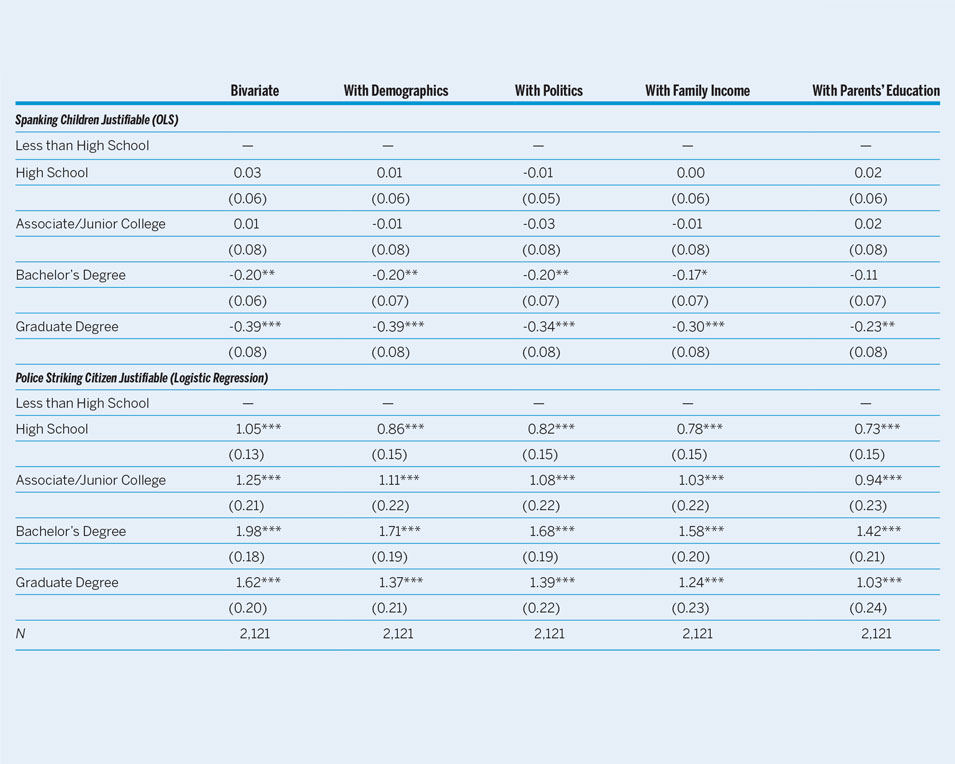

Table 3 presents parallel results for the GSS on measures of interpersonal violence (i.e., whether corporal punishment can be necessary) and state-sanctioned violence (i.e., whether police violence can be necessary). Similar to WVS patterns, Americans with more education were less likely to say that parents hitting children is justifiable but more likely to say that police hitting citizens is justifiable. Again, women tended to be against both interpersonal and state-sanctioned violence, and the impact of nonwhite racial categories is generally the inverse of those for education.Footnote 4 Therefore, it again tended to be highly educated white men who espoused the establishment value of state-sanctioned violence. The general patterns again persisted although they were somewhat attenuated as other covariates were added to the models. Some of these covariates (e.g., income) were deeply intertwined with education and could be pathways by which education influences attitudes.Footnote 5

Table 3 Education Predicting Justifiability of Violence, US General Social Survey

Source: General Social Survey, 2010–2014.

Standard errors are in parentheses.

Notes: All models include binaries for survey year. Demographics model adds gender, race/ethnicity, age, region, marital status, and parental status. Politics adds political views and party identification (all previous covariates are retained when covariates are added to sequential models). Family income adds inflation-adjusted family income. Parents’ education adds mother’s and father’s education.

†p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

In both datasets, the impact of more educational degrees was typically ordered, with additional degrees making people increasingly different from those who did not finish high school. However, that was not the case for graduate education and attitudes toward state-sanctioned violence. Whereas more education appears to consistently socialize people into establishment values up through a bachelor’s degree, graduate education appears to function somewhat differently: some types of graduate education may promote antiestablishment values.Footnote 6

Readers may note that in both datasets the interpersonal-violence variables are ordered measures whereas the state-sanctioned violence measures are binary. I conducted additional analyses in which I dichotomized the ordered measures to better parallel the binary measures and make effect sizes more comparable. Supplemental figures S1 and S2 present predicted probabilities with controls held at global means that demonstrate the same pattern of more education decreasing support for interpersonal violence and increasing support for state-sanctioned violence—with a decrease in support for state-sanctioned violence among those with graduate degrees. Education tends to have a substantial impact on these attitudes. For example, Americans with less than a high school education were approximately three times as likely to find wife beating sometimes justifiable (i.e., predicted probability of 0.15) than those with a graduate degree (i.e., predicted probability of 0.04).

DISCUSSION

This study proposed a modified socialization model for how education shapes attitudes and applied it to Americans’ beliefs about which types of violence are justifiable. The development model and previous socialization model both predicted that education would lead people to think that violence by individuals and by the state is not justifiable. However, the results were consistent with my modified socialization model, which suggests that not only does education transmit individualistic and meritocratic libertarian values, it also can promote establishment interests (Jackman Reference Jackman1994; Jackman and Muha Reference Jackman and Muha1984). Americans with more education were less likely to say that interpersonal violence—against women, against children, and against other Americans—can be justifiable. However, they were more likely to say that state-sanctioned violence—war and police violence—can be justifiable. American education, therefore, appears to promote an establishment politics that differentiates between unacceptable interpersonal violence and ostensibly acceptable state-sanctioned violence.

American education, therefore, appears to promote an establishment politics that differentiates between unacceptable interpersonal violence and ostensibly acceptable state-sanctioned violence.

This brief study provides support for Phelan et al. (Reference Phelan, Link, Stueve and Moore1995) and others who argued that education socializes people to an “official culture”; however, it suggests that the American official culture is not purely libertarian and that education is more than a medium for the transmission of a set of ruling-class values. As Stubager (Reference Stubager2008; Reference Stubager2009; Reference Stubager2013) suggested, it is also an identity-building process. Breaking slightly from Stubager, however, I found that Americans with more education take on the values and interests of the educated class who gain from libertarian economics and government intervention to protect their interests (Jackman Reference Jackman1994; Jackman and Muha Reference Jackman and Muha1984).

Although attitudes toward violence were the specific case for a broader question about education and public opinion, these specific attitudes are important and timely in their own right. Based on popular assumptions, we might assume that American support for police brutality against citizens is most pronounced among certain uneducated groups (e.g., uneducated white men). However, in fact, belief in the justifiability of police violence extends to and appears to be especially strong among those with higher levels of education (and especially college-educated white men). Therefore, it appears to be those higher-class people most insulated from the risk of experiencing police violence—or having to go to war themselves—who were most likely to say that state-sanctioned violence might be necessary. Future research should examine further the particular conditions under which people of different educational levels would consider police violence and war justifiable.Footnote 7

Similar to how Phelan and colleagues (1995) improved on previous research by differentiating between social and economic values to substantiate a socialization model of education, this empirical test differentiated between interpersonal and state-sanctioned violence to refine the socialization model. Although social scientists typically think of education as challenging authority and debunking inequality-legitimating myths such as racism and sexism, it also can legitimate stratification and some forms of authority. Research has shown that people will accept actions that they otherwise would perceive as unjust if such actions were carried out by a legitimate authority (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Hegtvedt, Khanna and Scheuerman2016). Therefore, the legitimation of stratification and state-sanctioned violence has important real-world consequences. The results reported in this study suggest that new approaches and target audiences may be needed in attempts to counter acceptance of and complacency toward police brutality and other forms of state-sanctioned violence in the United States.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096518000094

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author is grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their comments.