During the last decades, the prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), comprising a wide spectrum of liver diseases ranging from simple hepatic steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), cirrhosis and even hepatocellular carcinoma( Reference Sass, Chang and Chopra 1 ), has dramatically increased. Indeed, Blachier et al. ( Reference Blachier, Leleu and Peck-Radosavljevic 2 ) has recently reported in a survey reviewing 260 epidemiological studies published in Europe during the last 5 years that NAFLD is by now the most frequent liver disease in Europe. However, in spite of intensive research efforts during the last decades, molecular mechanisms underlying the development of NAFLD remain mostly unclear, and universally accepted treatment strategies besides a life-style modification, such as weight-reduction diets and/or increases in physical activity are not yet available.

Butyrate, a naturally occurring SCFA in the body mainly produced by intestinal bacteria and found in various foods like cheese and butter, has in recent years been suggested to play an important role in maintaining intestinal homoeostasis( Reference Leonel and Alvarez-Leite 3 ). Indeed, it has been shown in in vitro studies that butyrate through AMP-kinase- and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent signalling cascades may ameliorate ethanol-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction( Reference Elamin, Masclee and Dekker 4 , Reference Huang, Li and Zhu 5 ). Recent animal studies further suggest that sodium butyrate (SoB) may also possess protective effects on liver damage of various aetiologies( Reference Mattace, Simeoli and Russo 6 – Reference Sun, Wu and Sun 8 ). For instance, it has been shown that rats treated before or at the onset of ischaemia reperfusion (I/R) with butyrate were markedly protected from I/R-induced liver injury not only through mechanisms involving inhibition of histone deacetylase and heat shock protein 70 induction in the liver as well as by maintaining the intestinal barrier structure( Reference Sun, Wu and Sun 8 ). In line with these findings, Cresci et al. ( Reference Cresci, Bush and Nagy 9 ) reported that pretreatment of mice with tributyrin, an ester composed of butyric acid and glycerol, protects mice from acute but not chronic alcohol-induced liver damage through mechanisms involving a protection against the loss of tight junction proteins induced by acute alcohol exposure. Furthermore, Mattace et al. ( Reference Mattace, Simeoli and Russo 6 ) showed that butyrate and its synthetic derivative N-(1-carbamoyl-2-phenyl-ethyl) butiramide may protect rats from the development of insulin resistance and NAFLD. However, not only whether butyrate also possesses protective effects on the development of NAFLD in other models of NAFLD, as well as the molecular mechanisms involved has not yet been determined.

Using a mouse model in which mice were pair-fed a fat, fructose and cholesterol-enriched liquid diet to induce NAFLD, the main objective of the present study was to test the hypothesis that an oral supplementation of SoB protects mice from the development of NASH and if so, to determine underlying molecular mechanisms involved.

Methods

Animals and treatments

Eight-week-old female C57BL/6J mice (Janvier SAS), which were indicated to be more susceptible to a fructose-induced NAFLD compared with the male mice by our own group( Reference Spruss, Henkel and Kanuri 10 ), were housed in a pathogen-free barrier facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. The local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures. During a 6-week feeding period, mice (n 6/group) were pair-fed either a standard liquid diet (control, 15·7 MJ/kg diet: 69 E% from carbohydrates, 12 E% from fat and 19 E% from protein) or a liquid Western-style diet (WSD; fortified with fructose, fat and cholesterol; 17·8 MJ/kg diet: 60 E% from carbohydrate, 25 E% from fat and 15 E% from protein with 50 %, w/w fructose and 0·155 %, w/w cholesterol) (Ssniff) ±0·6 g/kg body weight/d SoB (Sigma-Aldrich) (for details also see online Supplementary Table S1). All mice had free access to plain tap water. Diet consumption was assessed and adjusted daily, and body weight was registered weekly. After 4 weeks of feeding, mice were fasted for 6 h to obtain fasting blood samples from retrobulbar venous plexus for glucose measurements. After 6 weeks, mice were anaesthetised with the mixture solution of 100 mg ketamine/kg and 16 mg xylazine/kg body weight by intraperitoneal injection. Blood was collected just before killing. Liver and intestine samples were either fixed in neutral-buffered formalin or in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) embedding media (Medite) for the histological staining or frozen immediately in liquid N2 and were then kept in a −80°C freezer for the further experiments.

Histological evaluation of liver sections

Frozen sections of the liver fixed in OCT (10 µm) were stained with Oil red O (Sigma) as described previously( Reference Spruss, Kanuri and Stahl 11 ). Representative photomicrographs were captured at a 100× magnification using a system incorporated in microscope (Leica DM4000; Leica). Paraffin-embedded liver sections (4 µm) were stained with haematoxylin–eosin (Sigma) to evaluate histology. Representative photomicrographs were captured using a camera integrated in a microscope (Leica DM4000 B LED; Leica) at 200× magnification. NAFLD activity score was used to determine liver damage( Reference Brunt, Kleiner and Wilson 12 ). To determine number of neutrophilic granulocytes, liver sections (4 µm) were stained with Naphthol AS-D Chloroacetate Esterase kit (Sigma), and number of neutrophils was determined as previously described in detail( Reference Spruss, Kanuri and Stahl 11 ). Collagen deposition in the liver tissue was stained with Picrosirius red (Sigma) and counterstained with fast green (Sigma) to determine fibrosis. Quantitive evaluation of staining was carried out as previously described in detail( Reference Bergheim, Guo and Davis 13 ).

Blood parameter of liver damage and ELISA

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity was determined by a colorimetric reaction (Architect, Fa.; Abbott) in a routine laboratory. Fasting blood glucose levels were measured using a blood glucose meter (Contour; Bayer Vital GmbH). Protein concentration of TNF-α in the liver tissue was determined using a commercially available ELISA kit (Mouse TNF-alpha ELISA Kit; Assaypro) as detailed before( Reference Wagnerberger, Spruss and Kanuri 14 ).

Immunohistochemical staining of the liver and duodenum

Paraffin-embedded liver tissue sections (4 µm) were stained for myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88), 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) protein adducts, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), F4/80 and cluster of differentiation 8α (CD8α)-positive cells using polyclonal antibodies (MyD88: Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 4-HNE: AG Scientific; iNOS: Affinity BioReagents; F4/80: Abcam; CD8α: Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as previously detailed( Reference Bergheim 15 , Reference Spruss, Kanuri and Wagnerberger 16 ). Paraffin-embedded duodenal tissue sections (4 µm) were stained for the tight junction proteins occludin and zonula occludens 1 (ZO-1) using polyclonal primary antibodies (Life Technologies GmbH) as described previously( Reference Spruss, Kanuri and Stahl 11 , Reference Kanuri, Spruss and Wagnerberger 17 ). In brief, to detect the binding of target protein to the specific primary antibody, tissue sections were incubated with a peroxidase-linked secondary antibody and diaminobenzidine (Peroxidase Envision Kit; Dako). Pictures of eight fields of each tissue section (×200 of each liver tissue; ×400 of each duodenum tissue) were captured using a digital camera integrated in a microscope (Leica DM4000 B LED), and the extent of staining in tissue sections was defined as per cent of field area within the default colour range determined by an analysis system incorporated in microscope. Mean values of eight sections were used per tissue section to determine means.

RNA isolation and real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA from the liver tissue was isolated with Trizol (peqGOLD Trifast; Peqlab), and 1·0 μg total RNA was reverse transcribed (cDNA synthesis kit; Promega). SYBR Green® Supermix (Agilent Technologies) was used to prepare the PCR mix, and relative mRNA expression was determined using a MX QPCR System (Agilent Technologies) as previously detailed(

Reference Wagnerberger, Spruss and Kanuri

14

). PCR primers for chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL-2), toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4), insulin receptor (IR), IR substrate 1 (IRS-1), IL-1β, fatty acid synthase (FAS), sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c), transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) and eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2 (Eef-2) as well as 18S were designed using Primer 3 software (Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research). Sequences are listed in Table 1. The comparative cycle threshold (C

t

) method was used to determine the amount of target, normalised to an endogenous reference (Eef-2) and relative to a calibrator (

![]() $$2^{{{\minus}\Delta \Delta C_{t} }} $$

). The purity of the PCR products was verified by melting curves and gel electrophoresis.

$$2^{{{\minus}\Delta \Delta C_{t} }} $$

). The purity of the PCR products was verified by melting curves and gel electrophoresis.

Table 1 Primer sequences used for real-time RT-PCR detection

CCL-2, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2; TLR-4, toll-like receptor 4; IR, insulin receptor; IRS-1, insulin receptor substrate 1; FAS, fatty acid synthase; SREBP-1c, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor β1; Eef-2, eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2.

Western blot

A Dignum A buffer (1 mol/l HEPES, 1 mol/l MgCl2, 2 mol/l KCl, 1 mol/l dithiothreitol) containing a protease inhibitor mix (Roche) was used to homogenise liver tissue samples, and blots were prepared as previously detailed( Reference Landmann, Wagnerberger and Kanuri 18 ). Blots were probed with antibodies against inhibitor of NF-κB kinase (IKK) subunit β and phosphorylated IKK subunit α and β (Ser 176/180) (pIKKα/β) (both Cell Signaling Technology), and bands were visualised using a Super Signal Western Dura kit (Thermo Scientific). Equal loading of blots was ensured by Ponceau Red staining (Roth). Using a ChemiDoc MP System (Bio-Rad Laboratories), protein bands were detected and analysed.

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as means values with their standard errors. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was used to determine the statistical differences between the treatment groups (Graph Pad Prism version 6.0; GraphPad Software). Outliers were identified using Grubbs’s test. P value<0·05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Effect of an oral sodium butyrate supplementation on liver injury and markers of glucose metabolism

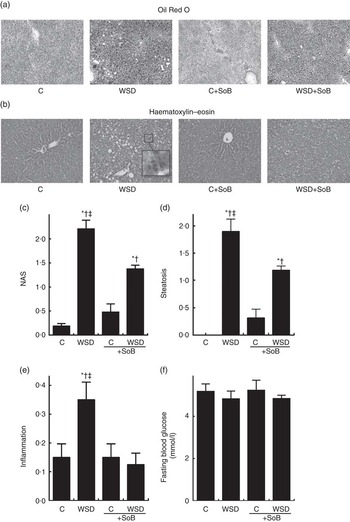

As expected, mice fed the WSD developed massive macrovesicular steatosis associated with marked inflammatory alterations (see Fig. 1). In contrast, despite a similar energy intake, body weight gain and even a significantly higher liver:body weight ratio, mice fed a WSD supplemented with SoB (WSD+SoB) had a significantly lower number of fat infiltrated hepatocytes and displayed predominantly microvesicular fat accumulation in the liver (see Table 2, Fig. 1(a)–(d)). However, number of fat infiltrated hepatocytes in the WSD+SoB group was still significantly higher than that in both control groups (see Fig. 1(d)). Furthermore, number of not only inflammatory focis as well as neutrophils and F4/80 positive cells were only found to be significantly higher in livers of mice fed a WSD alone (P<0·05 in comparison with all other groups) (see Table 3 and Fig. 1(e)). In line with these findings, number of CD8α-positive cells in livers of mice receiving only WSD was also significantly higher than in those of mice fed the control diet or WSD+SoB. However, despite not showing any signs of inflammation, number of CD8α-positive cells was significantly higher in livers of mice fed the control diet supplemented with SoB (C+SoB) (see Table 3). Expression of CCL-2 mRNA was only found to be significantly higher in livers of WSD-fed mice when compared with all other groups (see Table 3). TNF-α protein concentration was only by trend higher in livers of mice fed the WSD alone in comparison with control mice (P=0·065) (see Table 3). In line with these findings, concentration of pIKKα/β was only significantly higher in mice fed the WSD alone (see Fig. 3(g) and (h)). A similar effect of the WSD feeding was not found in mice concomitantly fed SoB; however, data varied considerably in some groups. Expression of IL-1β mRNA was significantly higher in livers of mice fed only a WSD in comparison with controls; however, expression of IL-1β mRNA was also significantly higher in livers of both groups receiving SoB, irrespective of the diet fed (see Table 3). Sirius red staining of collagen deposition revealed no differences between the different treatment groups (see Table 3 and Fig. 2(a)). Expression of TGF-β1 mRNA in the liver of WSD-fed mice was significantly higher than that in both control groups. In livers of mice fed the WSD+SoB, TGF-β1 mRNA expression was only significantly higher than that in those of mice fed only the control diet (see Table 3). As mice only displayed the beginning of NASH and measurements varied considerably, ALT plasma levels did not differ between groups (see Table 2). Furthermore, fasting glucose levels did not differ between groups (see Fig. 1(f)). In contrast, expression of IR was markedly higher in livers of mice fed the WSD+SoB; however, as expression varied considerably in the control groups, differences only reached the level of significance for the comparison of the two WSD groups (see Table 2). Furthermore, although IRS-1 expression was significantly lower in livers of mice of all groups in comparison with controls, expression of IRS-1 did not differ between groups treated with SoB, irrespective of the diet fed (see Table 2).

Fig. 1 Effect of an oral supplementation of sodium butyrate (SoB) on the level of steatosis and inflammation as well as the level of fibrosis in the liver of Western-style diet (WSD)- or control diet (C)-fed mice. (a) Representative photomicrographs of Oil Red O staining (upper panel) of liver sections (100×). (b) Representative photomicrographs of haematoxylin–eosin staining (lower panel) of liver sections (200×). (c) Evaluation of liver damage using a non-alcoholic fatty liver disease activity score (NAS). Analysis of hepatic (d) steatosis and (e) inflammation using NAS. (f) Fasting blood glucose levels of mice. Values are means, with their standard errors represented by vertical bars. * P<0·05 compared with mice fed control diet, † P<0·05 compared with mice fed concomitantly control diet and SoB (0·6 g SoB/kg body weight/d), ‡ P<0·05 compared with mice fed concomitantly WSD and SoB (0·6 g SoB/kg body weight/d).

Fig. 2 Representative photomicrographs of stainings in liver and in duodenum of mice fed a Western-style diet (WSD) or control diet (C) ±sodium butyrate (SoB). (a) Sirius red staining of liver sections (100×). (b) Occludin and (c) zonula occludens 1 (ZO-1) staining of duodenum sections (both 400×). Staining of (d) myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88), (e) inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and (f) 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) protein adducts of liver sections (all 200×).

Table 2 Effect of an oral supplementation of sodium butyrate (SoB) on body weight, liver:body weight ratio and clinical parameter of liver damage as well as markers of insulin resistance in mice fed a Western-style diet (WSD) or control diet (C) (Mean values with their standard errors)

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; IR, insulin receptor; IRS-1, IR substrate 1.

* P<0·05 compared with mice fed with control diet.

† P<0·05 compared with mice fed with WSD diet.

‡ P<0·05 compared with mice concomitantly fed control diet and SoB (0·6 g SoB/kg body weight/d).

§ P<0·05 compared with mice concomitantly fed WSD diet and SoB (0·6 g SoB/kg body weight/d).

‖ IR and IRS-1 mRNA expressions were normalised to Eef-2 mRNA expression.

Table 3 Effect of an oral supplementation of sodium butyrate (SoB) on markers of inflammation and fibrosis in livers of mice fed a Western-style diet (WSD) or control diet (C) (Mean values with their standard errors)

CD8α, cluster of differentiation 8α; CCL-2, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor β1.

* P<0·05 compared with mice fed with control diet.

† P<0·05 compared with mice fed with WSD diet.

‡ P<0·05 compared with mice concomitantly fed control diet and SoB (0·6 g SoB/kg body weight/d).

§ P<0·05 compared with mice concomitantly fed WSD diet and SoB (0·6 g SoB/kg body weight/d).

‖ CCL-2, IL-1 β and TGF-β1 mRNA expressions were normalised to 18S mRNA expression.

Effect of oral sodium butyrate supplementation on tight junction protein levels in duodenum and on markers of the toll-like receptor 4 signalling cascade in the liver

As butyrate has been suggested to at least in part mediate its beneficial effects on the development of liver diseases through altering intestinal barrier function( Reference Yang, Wang and Li 19 ), we determined protein levels of the tight junction protein occludin and ZO-1 in tissue obtained from duodenum and mRNA expression of the endotoxin receptor TLR-4 as well as its adaptor protein MyD88 in the liver. Protein levels of occludin and ZO-1 were significantly lower in the duodenum of both groups fed a WSD irrespective of additional treatments when compared with both control groups (see Fig. 2(b) and (c), Fig. 3(a) and (b)). Expression of TLR-4 mRNA was significantly higher in livers of mice fed the WSD alone and in both groups fed diets supplemented with SoB when compared with controls (see Fig. 3(c)). In contrast, protein levels of MyD88 were only significantly induced in livers of mice fed a WSD, whereas MyD88 protein levels of all other groups were at the level of controls (see Fig. 2(d) and Fig. 3(d)).

Fig. 3 Effect of the oral supplementation of sodium butyrate (SoB) on tight junction proteins in duodenum, the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4)-dependent signalling cascade and markers of lipid peroxidation as well as the phosphorylation status of inhibitor of NF-κB kinase subunit α and β (pIKKα/β) in the liver of Western-style diet (WSD)- and control diet (C)-fed mice. Densitometric analysis of immunohistochemical staining for (a) occludin, (b) zonula occludens 1 (ZO-1), (d) myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88), (e) inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and (f) 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) protein adducts. (c) Expression of TLR-4 mRNA in liver, normalised to eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2 mRNA expression. Representative pictures (g) and densitometric analysis (h) of western blots of (pIKKα/β) normalised to IKKβ. Values are means, with their standard errors represented by vertical bars. * P<0·05 compared with mice fed control diet, † P<0·05 compared with mice fed WSD, ‡ P<0·05 compared with mice fed concomitantly control diet and SoB (0·6 g SoB/kg body weight/d), § P<0·05 compared with mice fed concomitantly WSD and SoB (0·6 g SoB/kg body weight/d).

Effect of oral sodium butyrate supplementation on inducible nitric oxide synthase protein levels and markers of lipid peroxidation

As it has been shown that TLR-4 mediates its effects also through an activation of iNOS subsequently leading to an increase in the formation of reactive oxygen species( Reference Spruss, Kanuri and Uebel 20 ), we determined iNOS and 4-HNE protein adduct levels in livers of mice. In line with the findings for MyD88, protein levels of iNOS were only found to be significantly induced in mice only fed a WSD, whereas in livers of those concomitantly treated with SoB while being fed the WSD, protein levels of iNOS were almost at the level of controls (see Fig. 2(e) and Fig. 3(e)). Similar results were also found for levels of 4-HNE protein adducts, also only being significantly higher in livers of mice fed a WSD when compared with controls (see Fig. 3(f)).

Effect of oral sodium butyrate supplementation on markers of hepatic lipid metabolism

Expression of SREBP-1c mRNA in the liver did not differ between WSD groups and was significantly higher than that in livers of control groups (see Fig. 4(a)). In contrast, expression of FAS mRNA was significantly higher in livers of WSD-fed mice when compared with all other groups. However, although being significantly lower in livers of mice fed WSD alone, FAS mRNA expression in livers of WSD+SoB-fed mice was still significantly higher than that in both control groups (see Fig. 4(b)).

Fig. 4 Effect of the oral supplementation of sodium butyrate (SoB) on markers of lipogenesis in livers of Western-style diet (WSD)- and control diet (C)-fed mice. Expression of (a) sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c) mRNA and (b) fatty acid synthase (FAS) mRNA in liver of WSD-fed mice. Expression of SREBP-1c and FAS was normalised to 18S. Values are means, with their standard errors represented by vertical bars. * P<0·05 compared with mice fed control diet, † P<0·05 compared with mice fed concomitantly control diet and SoB (0·6 g SoB/kg body weight/d), ‡P<0·05 compared with mice fed concomitantly WSD and SoB (0·6 g SoB/kg body weight/d).

Discussion

Up to now, life-style- or pharmaceutical-based interventions aiming to prevent the development but even more so the progression of NAFLD are still limited. Animal-based models resembling alterations found in patients with simple steatosis as well as NASH have been found to be useful tools to investigate possible molecular mechanisms involved in the development and progression of the disease and to evaluate new potential therapeutic and preventive strategies( Reference Kanuri and Bergheim 21 ). In the present study, a mouse model using a liquid fructose-enriched WSD was used to induce not only the early metabolic but also molecular changes associated with the development of NASH (e.g. steatosis, inflammation and insulin resistance). Indeed, chronic feeding of this type of diet produced pathological changes in the liver and also at the level of the intestine that resembles many of the early alterations found in humans with beginning NASH( Reference Sass, Chang and Chopra 1 , Reference Kanuri and Bergheim 21 , Reference Tilg and Moschen 22 ). Despite these similarities with the human situation, it needs to be emphasised that chronic intake of a pair-fed liquid diet containing 50 E% fructose, 25 E% fat and 0·155 %, w/w cholesterol by no means mimics all alternations found in humans with NAFLD; however, this kind of dietary model offers the possibility to study molecular mechanisms underlying the development of NASH. Furthermore, as dietary intake of animals can be adjusted between groups, this kind of model can also serve to determine efficacy of nutritional supplements or drugs in a more accurate way as differences in energy intake associated with different treatments can be accounted for. Here, this dietary model was used to determine whether an oral supplementation of SoB can protect mice from the development of NASH. Despite a similar intake of energy and weight gain in all feeding groups and no differences in ALT plasma levels, mice fed a WSD supplemented with SoB were markedly protected from the development of NASH. Indeed, these mice displayed less macrovesicular fat accumulation and almost no inflammatory foci in their livers. However, animals fed the WSD regardless of additional treatments did not yet display any marked histological signs of fibrosis in their livers, and TGF-β1 mRNA expression was also only slightly increased. Indeed, it was shown in a recently published study that mice fed a WSD in combination with drinking water enriched with high-fructose maize syrup for 16 weeks only showed mild signs of fibrosis( Reference Machado, Constantino and Tomasi 23 ), suggesting that feeding time in the present study might not have been long enough yet to induce fibrotic changes in the liver. In line with the histological findings with regard to fat accumulation and inflammation, a number of neutrophils and F4/80-positive cells as well as expression of CCL-2 mRNA and to a lesser extend protein levels of TNF-α and phosphorylation of IKKβ were also only markedly higher in livers of mice fed the WSD alone. These findings are in line with those of others, suggesting that the progression of hepatic injury to later stages – for example, NASH and fibrosis – largely depends on a CCL-2/CCr2 (chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2) -dependent recruitment of ‘inflammatory’ Ly-6Chi expressing monocytes into the liver( Reference Tacke and Zimmermann 24 ). Results of the in vitro studies of Ohira et al. ( Reference Ohira, Fujioka and Katagiri 25 ) indicate that butyrate may reduce CCL-2 and TNF-α expression. In line with our findings, results of others also suggest that the hepatoprotective effects of butyrate might at least in part stem from an inhibition of the NF-κB signalling cascade( Reference Qiao, Qian and Wang 7 ). In contrast, the induction of the expression of IL-1β found in WSD-fed mice was not attenuated in mice fed a WSD supplemented with SoB; however, supplementation of SoB per se seemed to have altered the expression of this pro-inflammatory cytokine in the liver. Indeed, expression of IL-1β in livers of controls fed SoB was almost at the level of that found in both WSD-fed groups. In line with these findings, the number of CD8α-positive cells shown to be recruited to the liver by IL-1β-dependent mechanisms( Reference Ben-Sasson, Wang and Cohen 26 , Reference Ben-Sasson, Hogg and Hu-Li 27 ) was also not only higher in the liver of WSD-fed mice but also in controls fed SoB. However, no signs of inflammation were seen in livers of these control mice. In in vitro studies of Ohira et al. ( Reference Ohira, Fujioka and Katagiri 28 ), it was shown that an incubation of macrophages with butyrate especially in the presence of endotoxin is associated with an increased expression of IL-1β. Furthermore, Mattace et al. ( Reference Mattace, Simeoli and Russo 6 ) also reported a non-significant approximately 2-fold increase in IL-1β expression and cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) protein levels in livers of control rats fed a diet enriched with butyrate (20 mg/kg body weight). However, similar to our own findings, in spite of the induction of IL-1β mRNA and COX-2 protein levels, Mattace et al. also reported that an oral supplementation of SoB protected rats from the development of a high-fat diet-induced NAFLD. In accordance with our findings, the protective effects in this study were predominantly associated with a protection against the development of hepatic inflammation rather than lipid accumulation( Reference Mattace, Simeoli and Russo 6 ). Further studies are needed to unravel molecular mechanisms involved in the anti-inflammatory effects of butyrate in spite of the induction of some pro-inflammatory cytokines and increased number of CD8α-positive cells found in the liver when SoB is supplemented. The lack of differences in ALT levels between groups found in the present study could be attributed to the fact that mice only displayed early signs of NASH and no overall impaired glucose intolerance. Indeed, it has recently been suggested that adipose tissue insulin resistance, high liver TAG content and low plasma adiponectin are major factors in the elevation of plasma aminotransferase levels in patients with NAFLD, although hepatic insulin resistance seems to be of lesser importance in this respect( Reference Maximos, Bril and Portillo 29 ). In the present study, blood glucose levels were similar between groups, whereas, in line with earlier findings of our group, expression of IR in liver was slightly lower in livers of mice fed a WSD, indicating that mice suffered from hepatic insulin resistance( Reference Spruss, Henkel and Kanuri 10 ). In contrast, in livers of mice concomitantly fed a WSD and SoB, IR expression was markedly higher than that in those only fed a WSD, suggesting that the supplementation of SoB protected mice from the development of hepatic insulin resistance. Interestingly, expression of IRS-1 was per se lower in livers of mice fed SoB regardless of the diet fed, which suggests that SoB may alter insulin signalling in the liver independent of other dietary factors. These findings need to be further investigated in future studies. However, contrary to the findings in the groups not receiving SoB, expression of IRS-1 in the liver did not differ between controls and WSD-fed mice. These findings are in line with those of other groups showing that supplementation of SoB may modulate insulin signalling and thereby may protect against the development of insulin resistance( Reference Gao, Yin and Zhang 30 , Reference Matis, Kulcsar and Turowski 31 ). Indeed, it has recently been shown that treating chicken with 0·25 g/kg body weight SoB resulted in a marked decrease in protein levels of the IR β subunit in the liver and overall systemic insulin sensitivity( Reference Matis, Kulcsar and Turowski 31 ). Furthermore, in line with the findings of our study for the liver, it has also been shown in mice fed a high-fat diet, that supplementation of 5 %, w/w SoB protected animals markedly from the development of insulin resistance( Reference Gao, Yin and Zhang 30 ). Taken together, our data suggest that SoB supplementation in spite of the induction of some pro-inflammatory markers in the liver may protect mice from the development of NASH and hepatic insulin resistance.

The protective effect of a sodium butyrate supplementation is associated with a protection of mice from the induction of the toll-like receptor 4 signalling cascade, lipid peroxidation and the induction of fatty acid synthase in the liver.

It has been repeatedly suggested by not only the results of human studies of our own lab but also those of other groups that an increased translocation of bacterial endotoxin and activation of TLR-dependent signalling cascades in the liver may be involved in the development of NAFLD( Reference Kanuri, Ladurner and Skibovskaya 32 – Reference Thuy, Ladurner and Volynets 34 ). Results of recent studies suggest that SoB may exert its protective effect on the liver and maybe also on metabolic alterations through its effects on intestinal barrier function( Reference Leonel and Alvarez-Leite 3 , Reference Wang, Wang and Wang 35 , Reference Ma, Fan and Li 36 ). Furthermore, we and others showed before that the development of NAFLD is associated with a loss of tight junction proteins in the upper parts of the small intestine, increased bacterial endotoxin levels in the portal vein, the elevated expression of TLR in the liver and with the activation of dependent signalling cascades( Reference Wagnerberger, Spruss and Kanuri 14 , Reference Miele, Valenza and La 33 ). It was further shown that a protection against the loss of tight junction proteins in the upper parts of the small intestine is associated with lower endotoxin levels and a protection of the liver from the development of NAFLD( Reference Spruss, Kanuri and Stahl 11 , Reference Volynets, Kuper and Strahl 37 ). However, in the present study, protein levels of the tight junction protein occludin and ZO-1 were both lower in mice fed a WSD regardless of additional treatments, suggesting that protective effects of the supplementation of SoB found in the present study did not primarily stem from a protection against the loss of intestinal integrity. Differences between the results of the present study and those of other groups might have resulted from differences in the aetiology of liver disease( Reference Cresci, Bush and Nagy 9 , Reference Liu, Qian and Wang 38 ), for example, acute alcohol-induced liver damage and I/R, respectively, v. long-term feeding of a WSD and animal species used (rats v. mice). Furthermore, Cresci et al. ( Reference Cresci, Bush and Nagy 9 ) fed tributyrin in their experiments, and Endo et al. ( Reference Endo, Niioka and Kobayashi 39 ) treated animals with a butyrate-producing probiotics, whereas in the present study mice were fed SoB. Results of the present study suggest that the protective effects that were found stem from an attenuation of the induction of TLR-4-dependent signalling cascade and herein especially the induction of iNOS and an increased lipid peroxidation (e.g. formation of 4-HNE protein adducts) found in livers of mice fed a WSD. Indeed, it was shown before that iNOS is critical in regulating not only NF-κB-depending signalling cascades in the development of NAFLD but also the expression of the TLR-4 adaptor protein MyD88( Reference Spruss, Kanuri and Uebel 20 ). In line with our findings, Qiao et al. ( Reference Qiao, Qian and Wang 7 ) showed that the protective effects of SoB treatment against hepatic I/R damage were associated with a protection against the activation of NF-κB-depending signalling pathways in Kupffer cells. Mattace et al. ( Reference Mattace, Simeoli and Russo 6 ) also found that insulin resistance and NAFLD were associated with a marked attenuation of the induction of NF-κB-depending signalling cascades in the liver; however, in this study the protective effect of the butyrate supplementation was associated with a protection against the induction of TLR-4. Differences between the findings of Mattace et al. ( Reference Mattace, Simeoli and Russo 6 ) and our study might have resulted from differences in experimental setups – for example, high-fat diet fed to rats v. WSD fed to mice. However, Mattace et al. ( Reference Mattace, Simeoli and Russo 6 ) also found a marked protection of animals against the induction of iNOS in the liver. Results of Endo et al. ( Reference Endo, Niioka and Kobayashi 39 ) further indicated that a dietary supplementation of butyrate-producing probiotics probably resulting in increased formation of butyrate in the intestine attenuates the induction of SREBP-1c mRNA in the liver. In our study, despite not affecting mRNA expression of SREBP-1c in livers of WSD-fed mice, treatment with SoB significantly attenuated the induction of FAS mRNA expression in the liver. Differences between the present study and that of Endo et al.( Reference Endo, Niioka and Kobayashi 39 ) might have resulted from differences in study design (e.g. WSD-induced NASH v. CDAA (choline-deficient L-amino-acid-defined diet)-induced NASH and oral feeding of sod v. feeding of butyrate-producing probiotics). Furthermore, Endo et al.( Reference Endo, Niioka and Kobayashi 39 ) determined SREBP-1c protein levels in nuclear extracts, whereas in the present study we only determined mRNA expression. Indeed, it has been shown before that SREBP-1c is regulated not solely at the level of expression but also through cleavage of its membrane-bound precursor( Reference Wang, Sato and Brown 40 ). Therefore, it might be that the lack of response of SREBP-1c mRNA expression in livers of WSD+SoB-fed mice despite the down-regulation of FAS mRNA expression in livers of these mice might have resulted from a regulation of this nuclear factor at the level of protein activation rather than a regulation at the level of transcription. Taken together, not only the results of our study as well as those of other groups( Reference Mattace, Simeoli and Russo 6 , Reference Cresci, Bush and Nagy 9 ) suggest that butyrate may protect mice and rats from the development of liver damage; however, molecular mechanisms involved not only in the protection against the induction of iNOS and lipid peroxidation as well as in the down-regulation of FAS remain to be determined.

Conclusion

Taken together, our data suggest that an oral supplementation of SoB at least partially protects mice from the development of dietary-induced NASH. Our data further suggest that these protective effects not primarily resulted from a protection against the enhanced intestinal permeability and associated translocation of bacterial endotoxins found in mice with NASH but rather resulted from an inhibition of the induction of iNOS and subsequently a decreased formation of reactive oxygen species and induction of dependent signalling cascades in the liver. However, additional studies are necessary to (1) further explore underlying mechanism and to (2) determine whether similar beneficial effects of an oral supplementation of SoB are found also in humans.

Acknowledgements

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) measurement was carried out by the Centralised Diagnostic Laboratory Services of the Jena University Hospital.

The present project has been funded by Federal Ministry of Education and Research (FKZ: 01EA1305 to I. B.).

The contribution of the authors was as follows: I. B. designed research; C. J. J., C. S., A. J. E. and D. Z. conducted research; C. J. J. and D. Z. analysed data; C. J. J. and I. B. wrote paper; and I. B. had primary responsibility for the final content.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1017/S0007114515003621