1. Introduction: Telecollaboration and flipped classrooms in teacher education

The importance of innovation and research into initial teacher education is not a new topic in academic circles. The debate has reached far beyond university levels as governmental policymakers weigh in on key issues of teacher preparation for primary- and secondary-level teaching (Dooly & O’Dowd, Reference Dooly, O’Dowd, Dooly and O’Dowd2012). In a 2010 study on teacher education across 14 countries, it was revealed that there is a widely extended push by governments around the world “to enhance the professional knowledge base of teaching” (Menter, Hulme, Elliot & Lewin, Reference Menter, Hulme, Elliot, Lewin, Baumfield, Britton, Carroll, Livingston, McCulloch, McQueen, Patrick and Townsend2010: 11), highlighting in particular “the relationship between theory and practice, between pedagogical skills and subject knowledge and between values and technical competence” (p. 18). In kind, studies show that technology-enhanced teacher education can help support what Kumaravadivelu (Reference Kumaravadivelu2006) describes as the need for rich environments where future teachers can theorize on their practice and put into practice those theories in an iterative reflective cycle. Unsurprisingly, the use of technology to create “digital spaces” of collaborative learning is an increasingly popular means of engaging pre-service teachers in cross-cultural, international peer reflection and dialogic learning (Dooly, Reference Dooly, Chapelle and Sauro2017; Guichon, Reference Guichon2009; Hubbard & Levy, Reference Hubbard and Levy2006; McNeil, Reference McNeil2013). Telecollaboration (also known as virtual exchange) is the process of communicating and working (a/synchronously) together with other people or groups from different locations through online or digital tools to co-produce a desired work output. In education, telecollaboration combines all of these components with a focus on learning, social interaction, dialogue, intercultural exchange, and communication (Dooly, Reference Dooly, Chapelle and Sauro2017).

The use of telecollaboration (or virtual exchange if preferred) in education has taken root among a growing number of educators, as witnessed by specialized journals, conferences, and professional associations. In a keynote speech from 2016,Footnote 1 renowned theorist Dr David Little challenged researchers and practitioners of telecollaborative exchanges to take a critical look at what they are doing in order to evaluate whether such practices are really pushing the boundaries of teaching and learning. In particular, Little expressed concern that some telecollaborative exchanges may not be designed to genuinely promote increased learner responsibility and dialogic learning (cf. Alexander, Reference Alexander, Cowen and Kazamias2009) as is often claimed in published studies on these practices.

Still, despite a growing interest in technology-afforded distant exchanges for language teaching and learning, the notion of “connecting” language students through digital media is hardly new in education (see Dooly & O’Dowd, Reference Dooly, O’Dowd, Dooly and O’Dowd2018), and the expansion of this practice has resulted in a flurry of different terms, often applied as synonyms and in other cases stimulating heated debate on the best terminology to use:

As O’Dowd (Reference O’Dowd, Thomas, Reinders and Warschauer2013, p. 124) points out, the use of the Internet to connect online language learners for different types of learning exchanges “has gone under many different names”. These range from “virtual connections” (Warschauer Reference Warschauer1996), “teletandem” (Telles Reference Telles2009), “globally networked learning” (Starke-Meyerring & Wilson Reference Starke-Meyerring and Wilson2008) to the more generic term of “online interaction and exchange or OIE” (Dooly & O’Dowd, Reference Dooly, O’Dowd, Dooly and O’Dowd2012), to name just a few terms. It appears that the term Virtual Exchange is being used increasingly in a wide range of contexts. (…) it is also the term being increasingly used by foundations, governmental and inter-governmental bodies. (Dooly & O’Dowd, Reference Dooly, O’Dowd, Dooly and O’Dowd2018: 15)

Following these authors, “for the sake of simplicity and cohesion, and reflecting the long tradition of telecollaborative research in foreign language education”, we “use the term telecollaboration” (Dooly & O’Dowd, Reference Dooly, O’Dowd, Dooly and O’Dowd2018: 15–16) in this article to describe the distanced-partners’ collaborative exchanges described herein.

Likewise, the use of technology to generate a flipped classroom approach (sometimes called “flipped learning”, “the inverted classroom”, or “simply, the flip”; see Arnold-Garza, Reference Arnold-Garza2014: 8) is also growing in popularity among educators. Ideally, flipped instruction is more than merely having students complete activities outside the classroom that were traditionally done inside the classroom (e.g. viewing of recorded mini-lectures); this approach should be seen as placing emphasis on active learning, both inside and outside the class. It is important to clarify our understanding of flipped instruction as different from telecollaboration. Although both involve outside the classroom work, the students may engage with the flipped materials individually (human-to-computer interaction), whereas, according to the definition provided previously (Dooly, Reference Dooly, Chapelle and Sauro2017; see also O’Dowd, Reference O’Dowd2018), telecollaboration consists of human-to-human interaction mediated through computer or digital technology.

Moreover, while both flipped learning and telecollaboration have the potential to enhance the learning process, neither approach guarantees that this will immediately occur. Both approaches require teacher know-how of effective instructional practices in order to coherently sequence the tasks (both in and out of class) to ensure meta-cognitive scaffolding. Teachers must design intricately meshed tasks that support the identified learning goals, promote group awareness of the importance of collaborative learning, ensure knowledge acquisition, and promote positive attitudes regarding self-directed learning.

This was the main impetus that led the authors to develop a pedagogical design for language teacher education that we have chosen to call “the FIT” design (flipped instruction, in-class instruction, and telecollaboration; Sadler & Dooly, Reference Sadler and Dooly2016). The design emerged from 13 years of telecollaborative exchanges between their two classes as the authors gained more empirical understanding of flipped instruction and collaborative online work supported through different types of technology. In the first part of this article the evolution of the FIT design is outlined. We next describe the course, relating it to theoretical studies that have preceded this text and which have influenced our conceptualization of the course. Then, taking a descriptive, qualitative analysis approach (Creswell & Miller, Reference Creswell and Miller2000; Denzin, Reference Denzin1989), we apply discourse analysis (DA) to fragments of communication (oral, textual, visual). The chosen fragments make up “episodes” (Van Dijk, Reference Van Dijk and Tannen1982) that were collected during the fall course of 2016–2017 (the 14th iteration of telecollaboration between the two courses). Through the analysis of these episodes, we attempt to answer Little’s (Reference Little, Jager, Kurek and O’Rourke2016) questions: Does this technologically enhanced instructional design help promote learner responsibility and dialogic learning? Also, do these future teachers demonstrate uptake of conceptual knowledge regarding the potential use of this format in their own teaching?

2. Theoretical underpinnings of FIT

The principal theoretical underpinnings of the FIT model lie in the work of Vygotsky’s (Reference Vygotsky1986) proposal that learning takes place through mediated action – that is, through social interaction. Additionally, we draw from Alexander’s (Reference Alexander2008) study of classroom teaching in five different countries, which highlights the role of dialogue in the learning process. However, as Alexander points out, this does not mean that simply “talking” is enough. Although discussion as part of reflective practice is important, it does not necessarily guarantee that student teachers will be able to bridge the gap between theory and practice (Akbari, Reference Akbari2007; Edwards & Protheroe, Reference Edwards and Protheroe2003). The classroom organization and a supportive environment are essential for ensuring that the talk leads to (a) uptake of ideas, (b) scaffolding to ensure conceptual understanding, and (c) handover – that is, successful transfer and assimilation of new knowledge into already existing knowledge and understanding. Larrivee (Reference Larrivee2000) reported learning gains through dialogic learning in pre-service training, and other scholars have found similar results in online (telecollaborative) student-teacher discussion (Dooly, Reference Dooly2009; Dooly & Sadler, Reference Dooly and Sadler2013; Fuchs, Snyder, Tung & Han, Reference Fuchs, Snyder, Tung and Han2017; Guichon, Reference Guichon2009; Love & Simpson, Reference Love and Simpson2005; Sadler & Dooly, Reference Sadler and Dooly2016).

The pedagogical design of the FIT proposal integrates these notions of dialogic learning, supported through the carefully orchestrated organization of “dialogic spaces”, both in class and online, to generate what has been called the “microgenesis of learning” (Antoniadou, Reference Antoniadou2011a, Reference Antoniadou2011b; Saada-Robert & Balslev, Reference Saada-Robert, Balslev, Moro and Rickenmann2004); that is to say, a diachronic, socially situated learning process that is articulated through context (in class, online), participants (class and telecollaborative students and teachers), artifacts (in-class and flipped materials, output produced online and in class), and the participants’ shared understanding of the meaning(s) that are intersubjectively constituted through all of these features. The underlying purpose of the discussions and collaborative activities concerning the flipped materials, conducted both in class and online (and, arguably, with “self”), aim to promote “transformative reflection”, as defined by Naidoo and Kirch (Reference Naidoo and Kirch2016); that is, “a form of active learning in which individuals work collectively to pose problems that emerge in their experience from acting in the world” (p. 379).

3. The FIT design

3.1 Evolution of the FIT design

The exchange between the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UoI) began in 2004 and has continued, non-stop, since then. The students at UAB are in their final (fourth) year of their first degree of teaching and the UoI students are at the master’s level. In 2004, the collaboration between the two language-education teaching methodologies courses began with a small component of the main curriculum for each class, carried out through email exchanges. As the knowledge base and experience of the teacher educators grew over the years (as well as advances in communication technology), the telecollaborative exchange gradually became more fully integrated as a core part of the curriculum, shifting the focus of the telecollaborative activities from being peripheral to becoming the central nexus for the learning process. Thus the future language teachers were expected to actively engage in communicative online situations that promoted learning (content and language) so that they could then reflect on how they could transfer this knowledge to similar contexts for their pupils. By 2009, the two teacher educators had designed their course program together (even though they are presented in each university program as different subjects with their own enrolment codes), with the same activities and objectives and similar evaluation process, which even includes peer evaluation across international borders. In recognition of the sustained collaboration, the two universities signed statements of “mutual agreement of collaboration for teaching and research” that provided further support to the continuity of the teaching approach.

3.2 FIT: Flipped, in class, and telecollaboration

Currently, the students of both classes now share core content in their programs (despite being registered in different universities on separate continents), and over 75% of collaborative work takes place between distanced peers online. The course program is written collaboratively between the two teachers, resulting in the same sequencing of activities and materials for the students at both universities. Since 2010, in addition to the telecollaborative component, “flipped class” activities were added. Student teachers are expected to complete weekly activities in their own time – activities that may serve as preparation for their online group meetings (telecollaboration), the in-class sessions, or both.

Flipped materials may be mini-videos, prepared in conjunction between the UAB and UoI teachers (and at times with other collaborators), reading assignments (often done in collaboration with other members of their online groups, with each group member being assigned different parts), interactive documents (e.g. Thinglink), interactive presentations, or online collaborative exams (created by the students themselves in a previous online meeting for different groups), to name a few examples.

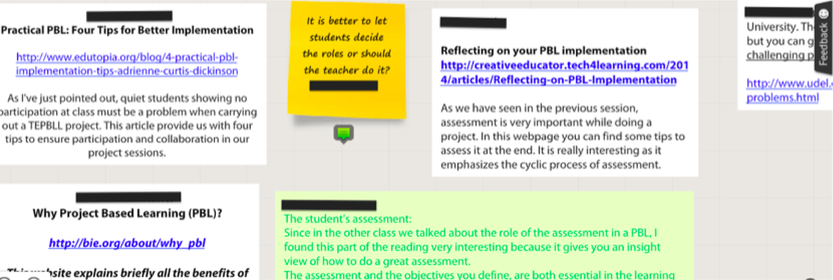

The following explanation aims to provide a glimpse into the way in which the online and in-class activities are intricately sequenced to most effectively scaffold the student-teachers’ self-directed learning process. Figure 1 shows the results of an online activity done early to mid semester (carried out on an online bulletin board) that required (a) reading a text (in this case, different texts about project-based learning), (b) highlighting the most relevant points, (c) searching for and proposing further supporting materials, and (d) finally posing a “burning question” that they, as future teachers, felt was still unanswered (names of students have been marked out for anonymity; see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Students’ posting of reflection, suggested materials, and questions

This activity was followed in a few weeks by telecollaborative discussions of questions that had been selected from the ones proposed (the teachers combined similar questions to come up with a manageable number of relevant questions). The following week, after both the individual “flipped” work and online discussions had been carried out, the students were asked to engage in further dialogical learning in class. These activities involved working in small pairs or trios (assigned according to the text they had previously read individually). After combining information based on their previous tasks (reading, online discussions), the pairs prepared a “mini-lesson” for the classmates who had not read their text. After “teaching” about their texts, new groups were formed to discuss and answer other issues that emerged from the mini-lessons and discussions. Notes from these discussions were shared online so that the observations could then form part of another online meeting in which the “burning questions” would be addressed.

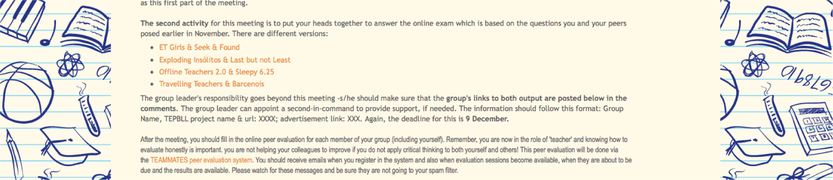

As the students carried out the activities, the design of the course aimed for sufficient iteration of the content in different contexts (individually online, collaboratively online, and in class with teacher and peers) to afford more opportunities for what Lynch, Mannix McNamara and Seery (Reference Lynch, Mannix McNamara and Seery2012) have called “deep learning”; that is, a multilayered understanding of complex issues that arises from considering the content of learning from multiple perspectives. The design also required them to be prepared with the materials by giving them the responsibility of “teaching” their peers about texts that the others had not read, encouraged them to reflect on their own learning process by explicitly stating what they had learnt, as well as verbalizing questions they still had. Moreover, continuous reflection tasks, such as that illustrated in Figure 2, allowed the teacher educators to cull their input towards more theoretical aspects. This reflective, collaborative learning even extended to the design and implementation of an online collaborative exam (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Instructions for a telecollaborative exam

Figure 3. Transcription of instructions for a telecollaborative exam (Figure 2)

The process of peer evaluation was continuous across all the activities (telecollaborative and in class) and included opportunities for the participants to indicate how well prepared their partners had been (thus providing indicators of the engagement they had had with the flipped class materials). This further supported the students’ growing awareness of the need to be responsible for their own learning, which is a principal foundation of both the flipped classroom approach (Arnold-Garza, Reference Arnold-Garza2014) and telecollaboration (Comas-Quinn, Reference Comas-Quinn2011; Fuchs et al., Reference Fuchs, Snyder, Tung and Han2017).

In summary, in the FIT design, the intensive preparatory work, driven by the flipped materials and the collaborative learning, not only introduces student teachers to conceptually demanding language teaching ideas but also provides the opportunity to gain empirical knowledge about technology-infused telecollaboration, through hands-on engagement with the materials, that the students may not have been exposed to otherwise. Just as the underlying paradigm of FIT does not contemplate lockstep, linear “trajectories of learning”Footnote 2 (Levine & Marcus, Reference Levine and Marcus2007: 118), the flipped materials are developed so that learning is dynamically mediated through many different types of artifacts and activities, both online and in class, and individually and collaboratively with others. Thus, the “talk” (in class and online) is supported and can hopefully lead to better understanding and assimilation of the concepts under discussion.

4. Discourse-based ethnographic study of FIT model outcomes

4.1 FIT: Participants and context

The data discussed in this article come from the fall 2016 exchange. The UAB class comprised 37 students and the UoI course had 14. All the participants were studying to become ESL/EFL teachers. During the 10 weeks in which the course calendars overlapped, the student groups met online on a weekly basis and carried out activities based on the flipped materials. These meetings resulted in a variety of outcomes. For instance, during some sessions the students worked towards creating group projects; in others, they produced materials to share with their in-class colleagues, or pooled knowledge stemming from their respective face-to-face classes to carry out activities assigned to the online groups (see Sadler & Dooly, Reference Sadler and Dooly2016).

4.2 Data compilation

In the first phase of data analysis, the researchers/authors chose the data to be used to illustrate the phenomenon under study. This was done by first compiling a corpus of different types of data:

video recordings of in-class discussions

video recordings of online small group discussions

individual reflections (grouped according to format: blog, podcasts, online presentations, digital posters, etc.)

peer evaluations concerning activity preparation, group work, and learner autonomy

self-evaluations regarding activity preparation, group work, and learner autonomy

group reflections (grouped according to format)

final projects (teacher booklets for a telecollaborative project).

These subsets were then grouped according to the episodes they represented (see section 4.4).

4.3 Data selection

Each of these data collections was viewed to select individual students whose trajectory could be “shadowed”. Two students were eventually chosen: Carlos and Alicia (names have been changed). These two were chosen because (a) they had regularly provided input during the course, and therefore comparable analyses could be made during the different phases, and were represented in all of the episodes selected to be studied; (b) one represented a student who was consistently marked quite high by peers with regard to willingness to collaborate with others and the other represented a student who began with a low assessment by peers and self. This afforded contrastive profiles of participants involved with the FIT design of activities. The shadowed students are both from the UAB because the UoI class did not have permission to video-record in class; however, there are data coming from online sources that include both UAB and UoI students.

The two “shadowed” participants were very similar in their educational background. Both Carlos and Alicia were in their fourth year of an undergraduate teaching program, taking a minor in teaching English as a foreign language in primary education. Both were multilingual, speaking Catalan and Spanish as “home” languages (equally fluent) and English as a foreign language. Carlos also had receptive skills (comprehension) of French and Italian. Carlos and Alicia had successfully completed three teaching internships in primary education schools but had no professional teaching experience at the time the data were collected.

4.4 Data analysis

This study falls within the parameters of descriptive, qualitative classroom ethnography, although we have amplified the boundaries of “classroom” to include online activities that formed part of the instructional design of the course. The use of “thick description” in qualitative analysis helps “readers understand that the account is credible” and “enables [them] to make decisions about the applicability of the findings to other settings or similar contexts” (Creswell & Miller, Reference Creswell and Miller2000: 129).

Taking “episodes” as our unit of analysis, we have applied DA to the compiled data to present what Warriner and Anderson (Reference Warriner, Anderson, King, Lai and May2017) call “a grounded and nuanced account of the specific, local, and complicated ways that institutional and social processes” (p. 300) converge (in this case, the instructional design and dual ecologies of in-class and online participation). DA is an established framework for in-depth understanding of occurrences in educational settings (Rogers, Malancharuvil-Berkes, Mosley, Hui & Joseph, Reference Rogers, Malancharuvil-Berkes, Mosley, Hui and Joseph2005; Rogers, Schaenen, Schott, O’Brien, Trigos-Carrillo, Starkey & Chasteen, Reference Rogers, Schaenen, Schott, O’Brien, Trigos-Carrillo, Starkey and Chasteen2016). As these authors indicate, DA has been widely used “to make sense of the ways in which people make meaning in educational contexts” (Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Malancharuvil-Berkes, Mosley, Hui and Joseph2005: 366). Episodes – which have been used as a framework for DA in other educational settings (cf. Schoenfeld, Reference Schoenfeld, Lesh and Landau1983) – can be used to describe class periods or smaller subsets of discourse such as group discussions, individual reflections, or online chats. We have chosen episodes to capture the sense of temporality and sequentiality belonging to a larger whole (in this case, two overlapping semester-long courses; cf. Van Dijk, Reference Van Dijk and Tannen1982). This allowed for a detailed look at temporality (selected moments that made up a longer, connected timespan; the overall course) and spatiality (in and out of class, face to face, and online). Specifically, the chosen episodes illustrate (a) in-class group discussions taken from the beginning, middle, and end of the course; (b) online discussions occurring at the beginning, middle, and end of the course; and (c) “inner dialogue” (posts, evaluations) at the beginning, middle, and end of the course.

Once the representative episodes had been selected (principal criteria being sustained presence of the two subjects), the fragments were analyzed using the DA approach deemed most suitable for the data type: conversation analysis for video recordings or content analysis for the text-based data. The transcription protocol is given in the Appendix.

5. Analysis and discussion

5.1 Student teachers take responsibility for their learning

Key to efficient flipped instruction is the acceptance, on behalf of the learner, that she or he is the principal agent in the learning process. On the other side, the teacher(s) must be willing to step back from the activity management, as “too much assistance also reinforces teachers as authoritative agents and limits students’ opportunities for learning” (Naidoo & Kirch, Reference Naidoo and Kirch2016: 385). Given that the learners in this study are studying to become teachers, learning about both sides of the coin – learner responsibility and teacher flexibility – are important.

Due to both the flipped nature of the activities and the integration of “sub-products” stemming from the different learning ecologies (online groups, individually at home, in class), the students were faced with the reality that they must organize and manage the workload efficiently from day one. This was reinforced by the design of online and in-class activities that usually required individualized but complementary contributions from each participant in order for the groups to be able to successfully complete the assigned online/in-class group activity. Followed routinely by peer evaluation for the activities, many of the students acknowledged that they had to “adjust” their working habits to be more “regular” and concise when preparing their “flipped instruction” assignments.

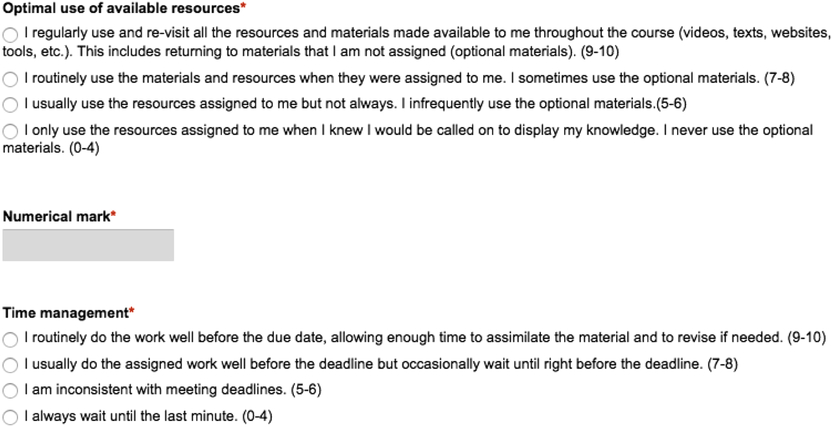

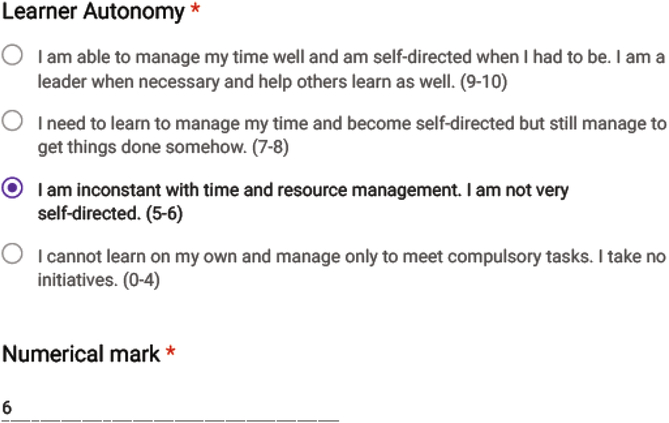

Students were asked to self-evaluate their learning habits at regular intervals during the course. Two of these times are considered in the following sections: once at the very beginning of the course (during the first day) and then three weeks into the course (an example of the online evaluation form can be seen in Figure 4). This second self-evaluation came immediately after having done a pair-work activity that required the contribution of each individual in order to be successfully completed.

Figure 4. Online evaluation form

The descriptors for peer evaluation of the discussion groups (both face to face and online) were based on studies concerning key factors for dialogic learning. Specifically, they aimed to foreground Alexander’s (Reference Alexander, Cowen and Kazamias2009) five principles of dialogic teaching and learning: that they must be collective, reciprocal, cumulative, supportive, and purposeful. To promote these principles in the in-class discussions (which were monitored by the teachers) and the online discussions (which were student-monitored only), the rubrics included descriptors related to effective discussion, reflection, and critical thinking (cf. Myhill, Reference Myhill2006; Simpson, Reference Simpson2010). Thus students were evaluated on different roles in the discussions (listener, discussion leader). Also, they were not just evaluated on the quality of their contributions (“output”) but also on how they contributed e.g. (willingness to listen to others, not monopolize conversations, provide support to others by encouraging turn-taking, etc.). At regular intervals during the semester, the peer assessments were collected and averaged, the comments were anonymized, and then general feedback was returned to the students on their performance in class. The online meetings were assessed through TEAMMATES and immediate feedback was delivered.

Looking more closely at the two “shadowed” students, in the first self-evaluation of learning habits, Carlos and Alicia both gave themselves high numerical marks by ticking the boxes related to scores of 9–10 in all of the categories. However, in the second evaluation, even before receiving the compiled averages from her peers and following a first meeting where she was not well prepared (according to peer review collected later), Alicia lowered her self-ranking to a range of 7–8 and even lower in the category of learner autonomy (see Figure 5).

It is important to underscore that these first evaluations and exchanges took place during the initial phase of the course, which aimed to foment the “interdependence” necessary for the students to move towards more autonomous learning. This phase comprised somewhat “institutionalized” pressure at the beginning of the course through “whole-group marks” (one evaluation of the final task for everyone in the group), followed by peer evaluations of group members’ preparation and contribution to the activity. This pressure (or “stress”, as the majority of the students called it in their reflection journals) was noted early on by almost all of the students in their journals, including both of the students in this study. In his first impressions, Carlos noted that the idea of this much responsibility felt “scary” and the amount of work seemed a bit overwhelming (Figure 6).

Students were given abundant leeway for deciding how to carry out both the reflection process (e.g. individually, in pairs, as group reflection concerning the learning process during the weekly online meetings) and the formats for documenting and collecting evidence of this process. The only requirements were that (a) the reflection process be continuous and sustained, and (b) that there be documentation (evidence) of the points they discuss in their final version that was delivered at the end of the course. In the case of collaborative reflection, an additional individual summary of their “personal learning trajectory” was compulsory. These could be made private or public as students preferred.

In Carlos’s case, he and a colleague (Andrea) decided to be “learner buddies” and meet on a weekly basis to discuss what they had done, learnt, and still needed to work on. Both students then chose clips from the recorded meetings to illustrate different points in their reflection diaries (a blog for Carlos). Carlos and Andrea decided to prepare questions for each other beforehand and meet at a prepared time. In the following fragment taken from an early recording, Carlos has asked Andrea about her expectations for the class (turn 1) and the discussion quickly turns to the anticipated workload and rapid pace of the course. Carlos claims, “I’m expecting a lot of- a lot of work” (turn 16), which is echoed by Andrea in turn 17: “I think that we we will have to work a lot a lot”. Carlos answers that it all seems a “bit scary” (turn 18), echoing what he had posted earlier in his reflection in Figure 6.

Fragment 1: Learner buddies’ discussion

Figure 5. Self-assessment of learner autonomy (Alicia)

Figure 6. Carlos’s screenshot (blog)

Interestingly, “scared” is the adjective employed by Alicia in her reflection journal (shown in Figure 7), which she chose to illustrate in short Powtoon videos. Similar to Carlos and Andrea, in one of her first postings (Alicia combined videos with a blog for her reflection journal), Alicia expresses worry about how to confront the class workload.

Figure 7. Alicia’s Powtoon (reflection journal)

As will be shown further on, however, Alicia gradually overcomes this “fear” and becomes very immersed in the different proposed activities.

5.2 Conceptual uptake: Theorizing what they practice and practicing what they theorize

Soon after the first posting Alicia received two cumulative peer feedback reports, which as has been noted earlier, were the lowest in the class. In a private email to the teacher following the first report, Alicia expressed anger and concern about the marks, noting that she felt they were “unfair” and she was uncomfortable being judged by her peers. Nonetheless, further on in the course she became notably more participative, both in class and online, which was reflected in the improvement of peer evaluations of her performance.

She also began to take more initiative as a group leader (even on days that she had not been assigned as leader), as we can see in the next fragment. The fragment comes from the last online group meeting (during which the students were engaged in an online collaborative exam) and Alicia takes the lead several times, although she was not the chosen leader. The question the students are discussing concerns different approaches towards evaluation of language learning. Alicia steers the discussion towards the issue of assessment and peer feedback several times (turns 44, 52, 56, 58), paying particular attention to ongoing (day-to-day) feedback. She is also very assertive about her own knowledge of the concept (turns 33, 35, 44, 52, 56, 58).

Moreover, Alicia insists that the answer the group has given corresponds to the correct answer in the exam (turn 30) – “ok it’s exactly what we said” – highlighting the group’s collective knowledge concerning methods of language assessment. This is an important feature of being both a teacher and a group leader: knowing how to orchestrate the learning process by helping others to identify their own knowledge.

Fragment 2: Collaborative online exam

Throughout this extract, Alicia appears to be the one who has the clearest concept of what continuous and formative assessments are and the benefits that can be derived from them. Considering that earlier in the course she had felt herself a “victim” of this type of assessment process, it is significant that she not only seems to have a deeper conceptual knowledge of the process, she appears to be a champion of this type of approach.

A bit later in the discussion (Fragment 3), Alicia “corrects” her mate Alina’s definition of continuous and formative assessment, highlighting that not only does the feedback provide input “so they can change and make any improvements” (turn 95) to what they are doing (96) but it is also about “giving feedback” to both teacher (which is what Alina has said) and students (turn 100). Alicia reiterates that this is what “they have been doing” (turn 129) as students and what they “should be doing” (turn 157) as teachers (in the project they are co-designing) because getting feedback supports learning (as has arguably occurred in her own learning process).

Fragment 3: Collaborative online exam

Finally, as the discussion nears the end, Alicia comes to the conclusion that assessment is about giving and receiving (a reciprocal process), which is a more attenuated view of evaluation than merely “marking” final products. As she states, “if you don’t improve what’s the point” (turn 160).

At the end of the course, in her individual reflection, Alicia posted a video about different aspects of “learning as a learner”, during which she reflected on the benefits of abundant feedback from different sources (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Alicia’s final “reflection” (Powtoon format)

Turning now to the other “shadowed subject”, Carlos also foregrounds the importance of learning to work collaboratively, both online and in class. Early in the course, Carlos had received low peer evaluations in only one area: willingness to listen to others and not monopolize the discussion. A previous study by Myhill (Reference Myhill2006) shows that “group work” does not necessarily transform to dialogic learning if the group does not allow equal voice, and a more authoritarian speaker may monopolize the conversation.

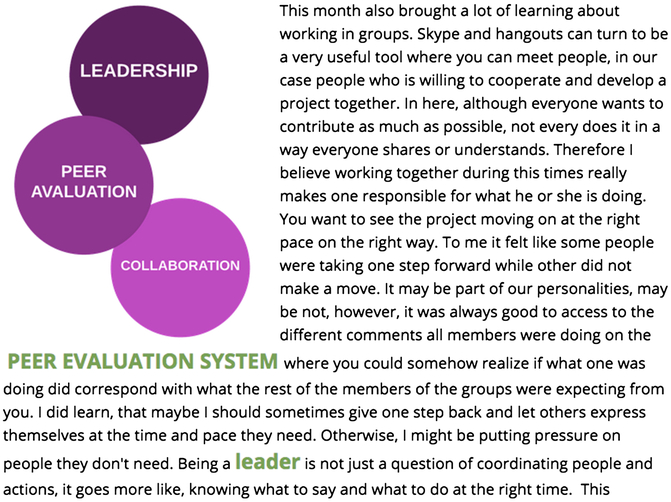

Later in the course, Carlos explains that an online learning buddy helped him become a better listener, which in turn contributed to being a better “team player” in the dialogic learning that took place in the online meetings. In his reflection blog, Carlos underscores the difficulties of working together (e.g. accepting that not everyone may contribute equally) as well as the complexities of being a good group leader (Myhill, Reference Myhill2006): “I did learn, that maybe I should sometimes give one step back and let others express themselves at the time and pace they need”. (…) “Being a leader is not just a question of coordinating people and actions”. It is also “knowing what to say and what to do at the right time”.

Similar to Alicia, Carlos highlights how the high expectations of the online group meetings (continuous assessment, need to prepare and deliver for specific tasks) can bring about positive changes towards becoming a more collaborative learner – it “makes one responsible for what he or she is doing” – while the peer assessment allowed the learner to position himself with regard to the others in the group.

5.3 Engaging in online dialogic learning for co-constructed conceptual understanding

In the previously analyzed online discussion group, the participants collectively struggle with both linguistic and conceptual knowledge of education-specific repertoires – in this case, assessment. In their ongoing dialogue, they are not merely searching for a definition, they are “internalizing” or “appropriating” “the external semiotic” resources (Antoniadou, Reference Antoniadou2011b: 63). In this way, words like “formative” and “continuous” are not only defined but also conceptually co-constructed so that the terms “acquire a specific significance and meaning for language teaching” (Antoniadou, Reference Antoniadou2011b: 65), which the student teachers can then apply to their own learning process. (There is evidence that they did this: all of the groups integrated the concepts accurately into their final project booklets.)

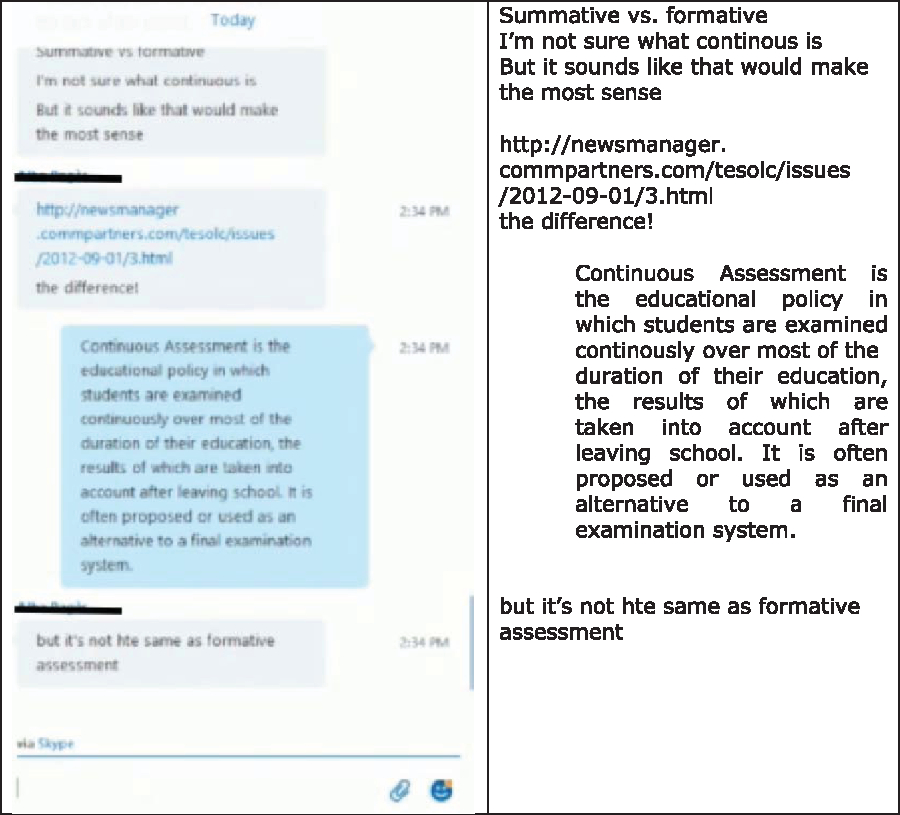

Early in the discussion, Ricardo (a member of Alicia’s online group) asks whether continuous and formative assessment are synonyms (which had been suggested previously) and then suggests that the terms should be looked up (turn 65): “we should google that before”. Anita and Alicia do not appear to take up the suggestion and continue debating the terms, but Alina (the group discussion leader who is in charge of the screen) begins a search, as indicated by the notes following turn 68.

Fragment 4: Collaborative online exam

Marcia joins Anita and Alina in the ongoing discussion of whether the two terms mean the same and soon thereafter several definitions of the terms have begun to appear in the online chat, contributed by different participants in the group (see definitions in Figure 10).

Figure 9. Carlos’s blog reflection

Figure 10. Definitions in text chat during Skype meeting

The definitions prompt more reflection on the two terms as the participants take time to read and consider the different options and opinions posted in the text discussion (turns 82 through 88 in Fragment 5). Rather than simply accepting a definition, the discussion then takes a more “pedagogical turn” as the group members begin to elaborate on the effects of feedback (information gathering or to improve) and whether it serves teacher, student, or both.

Fragment 5: Collaborative online exam

The participants then decide that if the input is only destined for the teacher, it is an “incorrect” answer for the examination they are doing together online, because that approach to assessment is for evaluative purposes only, and it is therefore not “formative”. The discussion has moved from a simple definition search to a meta-reflection of the impact the concept can have on the learning process.

As we have seen in several fragments and online output, the students frequently brought up the notion that they were “learning by doing”, and their discussions were often meta-reflections of their own learning supported through the possibilities afforded by the telecollaborative exchanges. This is exemplified in the group post that followed the “collaborative exam”. The reflection, posted by the group discussion leader but written and edited by the entire group, highlighted how the discussion brought about through the online collaborative exam had made them realize they “have learned more than [they] thought during this subject”.

The post also brings out another key learning aspect of their online collaborative work: dealing with complexity and the fact that there is not always a “black or white” answer, while at the same time gaining confidence in their knowledge and skills.

5.4 Transferal of knowledge

There is evidence of uptake of the content and materials from the course (which focused on effective use of technology-infused language teaching, in particular designing telecollaborative language learning projects). In the second semester, after having finished the course, Alicia agreed with a colleague from the course to design and implement a telecollaborative project between their language students in their internship. (Note that although the FIT course had officially ended by this time, Alicia contacted her teachers to notify them of this decision and gave permission to use her internship reflection blog.)

Figure 11. Transcription of Alicia’s internship reflection

Later in her reflection, regarding the implementation of the telecollaborative project, Alicia states:

First of all I would like to say that the TU was a success. I feel really proud and I consider that with my collaborative partner, together, we did a fantastic job. Here, communication and co-operation were key. The project was motivating for the students. In my class, sometimes I felt it was hard to motivate the pupils. (…) However, the idea of exchanging virtually our school reality with another group was meaningful for them. Since I played the first introductory video they got engaged.

She then goes on to list several theoretical underpinnings that she felt supported the language learning, including the importance of scaffolded online opportunities for communication and meaningful interaction. In summary, Alicia appears have a clear uptake of ideas presented in the course and has successfully transferred, assimilated, and transformed that knowledge into already existing knowledge in order to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

6. Summary of findings

Little (Reference Little, Karlsson, Kjisik and Nordlund2000) argues that teacher autonomy – and a willingness to instill learner autonomy in their own students – cannot be developed if the teachers themselves have not experienced how to be autonomous as learners:

The development of learner autonomy depends on the development of teacher autonomy. By this I mean two things: (i) that it is unreasonable to expect teachers to foster the growth of autonomy in their learners if they themselves do not know what it is to be an autonomous learner; and (ii) that in determining the initiatives they take in the classrooms, teachers must be able to exploit their professional skills autonomously, applying to their teaching those same reflective and self-managing processes that they apply to their learning. (p. 45)

The data appear to indicate that the FIT model gradually guides these future teachers to acceptance of their responsibility for learning. Summarizing the events of the two “shadowed” students over the course, we can see that at the beginning of the term Alicia first gives herself high marks in learning management, which she then quickly lowers even before receiving peer feedback, perhaps based on recognition that she was ill-prepared for the first online meeting. During the first part of the term, both students also underscore the pressure of continued evaluation and the need to complete deadlines in order to fully participate in all activities (in-class/online meetings). By midterm and onward, Alicia has begun to take more initiative as online discussion leader and orchestrates the learning process of both self and other participants. At the end of the term, both Carlos and Alicia acknowledge the importance of gradually placing fuller responsibility on the learner in these highly complex learning environments.

Field notes indicate that peer and self-assessment combined with activities designed to require participation based on being fully prepared with more personalized prior tasks were initially met with some resistance. However, this same pedagogical design seemed to gently “pressure” the students to self-manage and monitor their preparatory activities (reading, viewing of video content, preparing notes, presentations, etc.) for the online and in-class activities. At the beginning of the course, Alicia was angry about the role of continued assessment integrated into the telecollaborative process. Likewise, Carlos had received low peer reviews concerning his collaborative efforts (he was not seen as a team player). By midterm and onward, both students had repositioned themselves: Carlos had joined up with an online learner buddy to review the subject content and Alicia now championed the importance of formative assessment for learning.

With regard to Little’s (Reference Little, Jager, Kurek and O’Rourke2016) second question, the data demonstrate that the FIT model not only exploits the dialogic structure of telecollaboration to promote L2 learning (in this case, content-specific vocabulary for teachers such as lexicon for different types of assessment), but also promotes meta-reflection through dialogue regarding the content of the course; for instance, the online exam discussion demonstrates how the learners articulate and co-construct deeper understandings of key teacher terminology. There is also evidence of uptake in key concepts of the course, in particular how to design and implement a telecollaborative exchange as teachers. Perhaps most importantly, at least one of the two students in the study demonstrated the confidence to transfer similar innovative pedagogical approaches to their own future teaching practices (as indicated in the teaching unit that was planned in the second term).

In summary, there are identifiable episodes of the student teachers taking responsibility for their learning, of the participants demonstrating conceptual uptake as they theorize what they practice and practice what they theorize, and moments where the learners make use of the multiple opportunities afforded them for hybrid (online and in class) dialogic learning for co-constructed conceptual understanding of the highly complex pedagogical theories and models presented to them.

7. Limitations of the study

This study endeavors to take a micro-analytical, cross-sectional examination of several discursive events that make up a whole – in this case, the design and implementation of a course that combines flipped and in-class instruction with a telecollaborative exchange. This case offers a rich description of complex interaction between the participants; however, the findings cannot be interpreted as representative of the collective experience of all the participants, as might be done with a different type of analysis. It is not suggested that these findings can be generalized beyond this context, although it is proposed that the FIT design might be applied to other settings to try to replicate the positive results found here.

8. Final words

It is worth noting that two different student teachers who graduated from this course later went on to design and implement telecollaborative projects in primary schools. After being hired the following year (2017–2018) as primary education teachers in public schools, the two former students contacted the course instructors to tell them about their experiences. It was anecdotal but encouraging news for both authors. This news inspired the authors to contact 151 former students and to subsequently follow up this emic, interactional study with a second one that surveyed and interviewed 53 former students from a 16-year period, all of whom have taken part in the aforementioned teacher education course (Marjanovic, Dooly & Sadler, in press). Results from this more recent study indicate that of the respondents 54% of the former students are or have been involved in using telecollaboration in their own classrooms, and of these teachers, 56% are recent graduates (five years ago or less), which corresponds to the most intensively integrated period of the FIT model previously described. Another 30% of the former teachers who had not taken part in telecollaboration in their teaching declared that they intended to do so in the near future, explaining that their current job positions did not really accommodate to the possibility of doing so now. These numbers, along with the in-depth look at the teacher development process in the course, seem to back the argument that bringing in telecollaboration and flipped instruction into teacher education can have an impact on future teachers and that there is perceptible uptake of conceptual knowledge regarding the potential use of this format in their own pedagogical practices.

In a recent editorial article on educational research, Greener (Reference Greener2018: 857) poses the question: “How can we regain that excitement of Web 2.0 potential with learner-users constructing their learning in co-operation with their peers?” She then remarks that “there is no ‘silver bullet’ response to the knowing-doing gap” and argues for more “academic literature demonstrating the pedagogic benefits of skilful design of learning which incorporates technology” (Greener, Reference Greener2018: 857). We hope that our readers will feel similar excitement regarding the potential our proposal holds for teacher education.

Acknowledgements

This study has been supported through two projects: Preparing Future English Teachers With Digital Teaching Competences and the Know-How for Application to Practice: A Collaborative Task Between University Teachers, School Tutors and Pre-Service Teachers (2015 ARMIF 00010; Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca, Generalitat de Catalunya) and Evaluating and Upscaling Telecollaborative Teacher Education (EVALUATE), an Erasmus+ Key Action 3 project (578013-EPP-1-2016-1-ES-EPPKA3-PI-POLICY, 2016-2019). The authors would like to thank the reviewers and editors for their insightful comments, which have helped to greatly improve the original text.

Ethical statement

Written consent to use the class materials for research and teaching purposes was obtained at the beginning of the course during each year of iteration. Participants’ names have been changed in the transcripts and have been blocked out in captured screenshots.

Appendix

Transcription protocol

About the authors

Melinda Dooly holds a Serra Húnter fellowship as senior lecturer at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Her principal research addresses technology-enhanced project-based language learning, intercultural communication, and 21st century competences in teacher education. She is lead researcher of GREIP: Grup de Recerca en Ensenyament i Interacció Plurilingües (Research Centre for Teaching and Plurilingual Interaction).

Randall Sadler is an associate professor of linguistics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he teaches courses on computer-mediated communication and language learning (CMCLL), virtual worlds and language learning (VWLL), and the teaching of L2 reading and writing. He has published widely in these areas in journals, chapters, and books.

Author ORCiD. Melinda Dooly, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1478-4892

Author ORCiD. Randall Sadler, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7743-7049