A large proportion of violent, aggressive and antisocial behaviours emerges during adolescence and young adulthood.Reference Kennedy, Burnett and Edmonds1–Reference Fountoulakis, Leucht and Kaprinis5. Young males in particular seem to be more inclined to violent behaviour;Reference Liu4–Reference Herrenkohl, Maguin, Hill, Hawkins, Abbott and Catalano6 among them, hyperactivity, impulsivity, low tolerance for frustration and social provocations, and a risk-taking tendency seem to be associated with a greater tendency to violent behaviour.Reference Blair2,Reference Herrenkohl, Maguin, Hill, Hawkins, Abbott and Catalano6 As for the gender differences related to violent behaviour, males traditionally show higher rates of aggression than females, especially in terms of physical violence, whereas females exhibit a more indirect type of aggression.Reference Björkqvist7,Reference Megías, Gómez-Leal, Gutiérrez-Cobo, Cabello and Fernández-Berrocal8 Response disinhibition, impulsivity and risk-taking are also usually associated with substance use disorders (SUDs) and antisocial personality disorder.Reference Grant, Stinson, Dawson, Chou, Ruan and Pickering9–Reference Whiting, Lennox and Fazel12 Among these psychological variables, impulsivity may play a special role: it is the tendency to exhibit rapid, unplanned behaviour in response to a stimulus without assessing the long-term consequences, and it aims for immediate reward.Reference Chamorro, Bernardi, Potenza, Grant, Marsh and Wang10,Reference Nigg11,Reference Gerbing, Ahadi and Patton13 Impulsivity has its peak in adolescence and generally decreases with advancing age, owing to the development of cognitive control skills.Reference Chamorro, Bernardi, Potenza, Grant, Marsh and Wang10,Reference Steinberg14,Reference Galvan, Hare, Parra, Penn, Voss and Glover15 SUDs, and in particular alcohol use disorder, are also linked to an increased risk of aggression,Reference Eriksson, Romelsjö, Stenbacka and Tengström16 often jointly with the presence of antisocial traits and impulsivity.Reference Beck, Heinz and Heinz17,Reference Rolin, Marino, Pope, Compton, Lee and Rosenfeld18 There is a bidirectional relationship between high levels of impulsivity, externalising behaviour and SUDs.Reference Dougherty, Marsh, Moeller, Chokshi and Rosen19–Reference Jakubczyk, Trucco, Kopera, Kobyliński, Suszek and Fudalej22 Indeed, impulsivity and emotional regulation are closely associated with SUDs, although SUDs may sometimes be a coping strategy for the stress caused by adverse events.Reference Jakubczyk, Trucco, Kopera, Kobyliński, Suszek and Fudalej22–Reference Petit, Luminet, Maurage, Tecco, Lechantre and Ferauge24 Hence, impulsivity and emotional dysregulation might be triggering factors, but also consequences of SUDs, predicting possible relapse in individuals with this condition.Reference Jakubczyk, Trucco, Kopera, Kobyliński, Suszek and Fudalej22

Aims

The aim of this paper is to prospectively assess the risk of aggressive and violent behaviour among individuals with mental disorders in young (18–29 years old) compared with older age groups. We hypothesise that younger individuals will exhibit higher rates of aggressive and violent behaviour also controlling for a number of variables, including SUDs, impulsivity and externalising behaviour.

Method

Design overview and participants

Violence Risk and Mental Disorders (VIORMED) is a prospective cohort study with a baseline cross-sectional comparative design, followed by a 1-year follow-up observation period. This study included patients living in residential facilities and out-patients under the care of four Departments of Mental Health in northern Italy. Many details about both the study settings and the design can be found in previous publications.Reference de Girolamo, Buizza, Sisti, Ferrari, Bulgari and Iozzino25,Reference Barlati, Stefana, Bartoli, Bianconi, Bulgari and Candini26 Inclusion criteria were a primary psychiatric diagnosis and age between 18 and 65 years. Exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of organic mental disorder, intellectual disability, dementia or sensory deficits. The selection of these patients was based only on a comprehensive and detailed documentation (as reported in clinical records) of a history of severe violent behaviour(s).Reference Barlati, Stefana, Bartoli, Bianconi, Bulgari and Candini26

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Ethical approval was granted by the ethical committee of the coordinating centre (IRCCS Saint John of God, Fatebenefratelli, no. 64/2014) and by the ethical committees of all the recruiting centres.

Measures and assessments

Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical and treatment-related data and information about their history of violence were collected for all participants recruited. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis IReference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams27 and Axis IIReference First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams and Benjamin28 (SCID-I and SCID-II) were administered to confirm clinical diagnoses. Symptom severity, personal and social functioning were assessed using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale–Expanded (BPRS-E)Reference Dazzi, Shafer and Lauriola29 and the Specific Level of Functioning scale.Reference Montemagni, Mucci, Galderisi and Maj30

Aggression and violence, impulsivity and hostility were evaluated using the Brown–Goodwin Lifetime History of Aggression (BGLHA),Reference Brown, Goodwin, Ballenger, Goyer and Major31 the Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory (BDHI)Reference Buss and Durkee32 and the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale Version 11 (BIS-11).Reference Barratt33 Anger was measured using the State–Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2).Reference Lievaart, Franken and Hovens34 Details about these tools can be found in Barlati et al;Reference Barlati, Stefana, Bartoli, Bianconi, Bulgari and Candini26 all these tools have been validated in Italy.

Monitoring of aggressive and violent behaviour

The treating clinician, or a close family member for some out-patients, rated each participant on the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS)Reference Margari, Matarazzo, Casacchia, Roncone, Dieci and Safran35 every 2 weeks during the 1-year follow-up, giving a total of 24 MOAS evaluations for each individual. The MOAS includes four aggression subdomains: verbal, against objects, against self and interpersonal physical. In each evaluation the score ranges from 0 (no aggression) to 40 (maximum grade of aggression), so that the individual MOAS total weighted score for the 1-year period could range from 0 to 960. We will refer to the weighted MOAS total score (our primary outcome) simply as the MOAS score.

Statistical analyses

The analysis of aggressive and violent behaviour was conducted by evaluating the MOAS scores in all 24 assessments, and their trends were estimated by calculating cumulative means, modifying the technique outlined in Lawless & NadeauReference Lawless and Nadeau36 and in Canal & Micciolo.Reference Canal and Micciolo37

This approach, which uses the cumulative mean of all MOAS scores, produces a graphical display of the participants’ patterns of behaviour. In this framework, the estimation of cumulative means is rather simple. Going into detail, if k is the number of participants constant over time, t is the evaluation time (t = 1, 2, …, 24) and St is the total MOAS score observed over the interval [1, t] evaluated by adding up all the individual MOAS scores observed from the first up to the t-th evaluation, the cumulative mean function of the MOAS score at evaluation t is calculated as Mt = St/k. If Mt is the arithmetic mean of the MOAS scores at time t, then M 1 = m 1, M 2 = m 1 + m 2 and M t = m 1 + m 2 + …mt are the sum of the means of the MOAS scores observed up to time t. For instance, if the means of the MOAS scores observed at times 1, 2, 3 and 4 are 1.41, 0.95, 1.06 and 0.97, the cumulative means of the MOAS scores are 1.41, 2.36, 3.42 and 4.39 respectively.

To measure the pattern of aggression, the area under the corresponding curves (AUC) has been computed using a trapezoidal rule. It is interesting to note that, by the properties of the arithmetic mean, the mean of the AUCs for the 24 cumulative MOAS scores for each participant corresponds to the AUC for the cumulative means of the MOAS scores.

To compare categorical data, the χ2-test or Fisher's exact test was used as appropriate. For quantitative data, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Student's t-test was employed. The assumption of normality was investigated by a visual inspection of the distribution of variables using quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plots. The association between age and other quantitative variables was quantified using Pearson's correlation coefficient.

We used four different statistical techniques to explain the relationship between age and the pattern of aggression quantified using the AUC for the MOAS scores, all of which allow for a non-linear association: smoothing splines, local regression, super smoother and kernel smoother; an in-depth description of these techniques can be found in Venables & Ripley.Reference Venables and Ripley38

Finally, logistic regression was employed to quantify the prognostic role of age, adjusting for other selected variables, in predicting the probability of having one or more episodes of aggression.

The likelihood ratio test was used, at a level of significance of 5%, to assess whether age was a significant predictor of episodes of aggression, after adjusting for the effect of other variables; the 95% confidence intervals for the adjusted odds ratios were also calculated. All statistical analyses were carried out using R 3.6.2 for Windows (R Foundation for Statistical Computing)39 and the MASS package (version 7.3-51.4).Reference Venables and Ripley38

Results

Sample characteristics

We recruited 340 participants: 181 (53.2%) had a history of violence, whereas the remaining 159 (46.8%) were not know to have behaved violently during their lifetime. Of these 340 individuals, 177 (52.1%) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, 90 (26.5%) met criteria for a personality disorder and 73 (21.4%) had other mental disorders (bipolar disorder, 31; unipolar depression, 18; and severe anxiety disorder, 14). Of the total, 125 individuals (36.8%) were living in residential facilities and 215 (63.2%) were out-patients. Most (81.5%) were males. Table 1 shows sociodemographic and clinical characteristics stratified by gender. Significant gender differences were found for civil status, diagnosis, treatment setting and history of violence.

Table 1 Gender differences according to different sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

SUD, substance use disorder.

a. Bold denotes significance at P < 0.05.

A significant difference in mean age was found for a number of variables for the entire sample: as regards diagnosis, participants with personality disorders were younger (mean 42.5 years, s.d. = 10.7 v. mean 46.3, s.d. = 10.2); single participants were younger (mean 44.7 years, s.d. = 10.4 v. mean 47.7, s.d. = 9.7); employed participants were younger (mean 43.5 years, s.d. = 8.5 v. mean 46.1, s.d. = 11); and participants with a history of SUD were younger (mean 41.8 years, s.d. = 9.7 v. mean 46.1, s.d. = 10.5). As regards medication prescription patterns, there was no difference in mean age (additional data are given in Online Resource 1, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1047).

The percentage of single and unemployed participants was not significantly different between participants with and without history of violence. Participants with a history of violence had a significantly lower level of education, with only 26.0% achieving a medium-high educational level compared with 38.4% of participants without a violence history (P = 0.019); the educational level was also significantly different among the diagnostic groups (P = 0.027): 25.4% of participants with schizophrenia, 36.7% of those with personality disorders and 41.1% of those with other diagnoses achieved a medium-high educational level. As far as civil status is concerned, a highly significant difference (P < 0.001) was found when diagnostic groups were considered: 92.7% of participants with schizophrenia, 78.4% of those with personality disorders and 79.8% of those with other diagnoses were single.

Table 2 shows the correlation coefficients between age and scores on the selected rating scales. In general, they were low in absolute value (under |0.23|), but some of them showed a significant, if weak, association with age.

Table 2 Correlation coefficients between age and scores of selected rating scales

BPRS-E, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale – Expanded; BGLHA, Brown–Goodwin Lifetime History of Aggression scale; BIS-11, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale Version 11; BDHI, Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory; STAXI-2, State–Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2; SLOF, Specific Level of Functioning scale.

Age and MOAS scores

Fifteen participants (11 with a history of violence and 4 without) had more than two missing MOAS evaluations and so were not considered in these analyses. Participants with up to two missing MOAS evaluations were computed by the moving average estimation method.

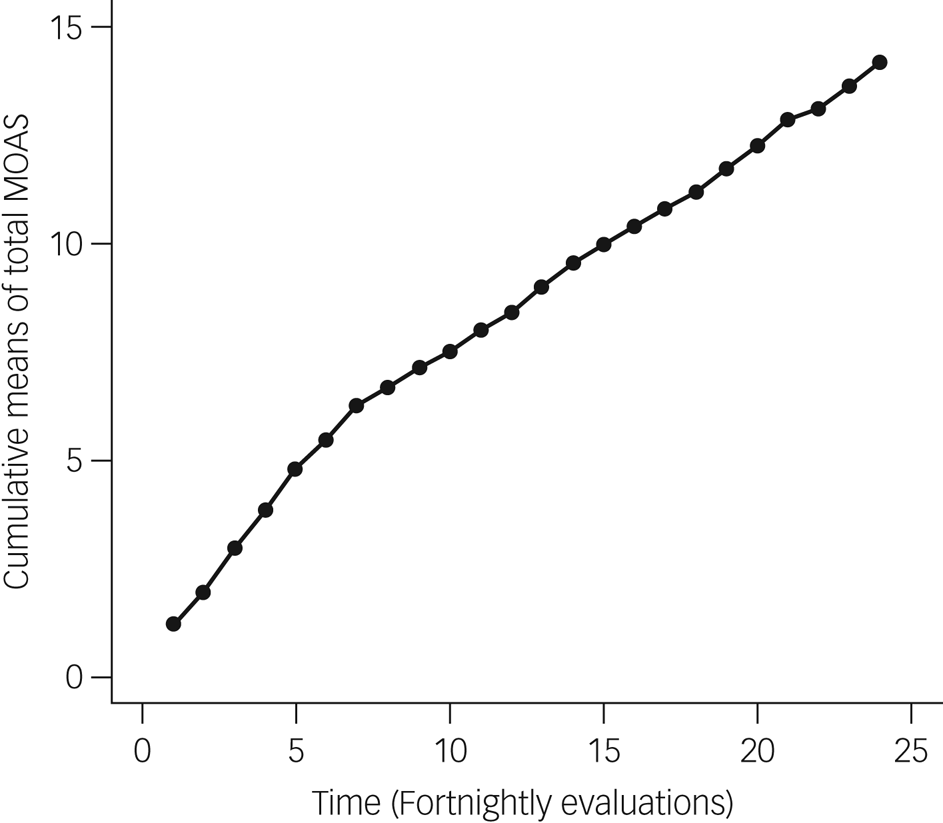

The cumulative MOAS mean scores (cMOAS) for the 24 fortnightly evaluations increased over time, with a clear two-phase linear trend (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Trend in cumulative means of total scores on the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS) over time.

More specifically, a linear increase was observed between the first and the seventh MOAS evaluations; the correlation between the evaluation time and the first seven cMOAS mean scores was 0.9988: therefore, in this time span, MOAS means remained approximately constant (around the value of 0.855). After the seventh and up to the last evaluation, the observed pattern of cMOAS was again linear (with a correlation of 0.9995) but with a lower slope (i.e. a lower aggression); that is, from MOAS points 7 to 24, MOAS means remained approximately constant (around the value of 0.467).

For 121 participants the AUC = 0 (i.e. all MOAS scores were equal to 0): 104 were males (37.5%) and 17 were females (27.0%); for the remaining 219 participants the AUC > 0, and of these 173 were males (62.5%) and 46 females (73.0%). Fisher's exact test yielded a P-value of 0.145, showing that these percentages were not significantly different between males and females.

Among participants with an AUC > 0, the mean age was 43.4 years for males and 43.6 years for females (s.d. = 10.4 and s.d. = 11.3 years respectively). Among participants with an AUC = 0, the mean age was 47.9 years for males and 52.6 years for females (s.d. = 8.9 and s.d. = 9.0 years respectively). An ANOVA showed that mean age was not significantly different between males and females (F = 1.12; P = 0.29), whereas the difference in mean age between participants with an AUC = 0 and those with an AUC > 0 was highly significantly (F = 20.4; P < 0.001).

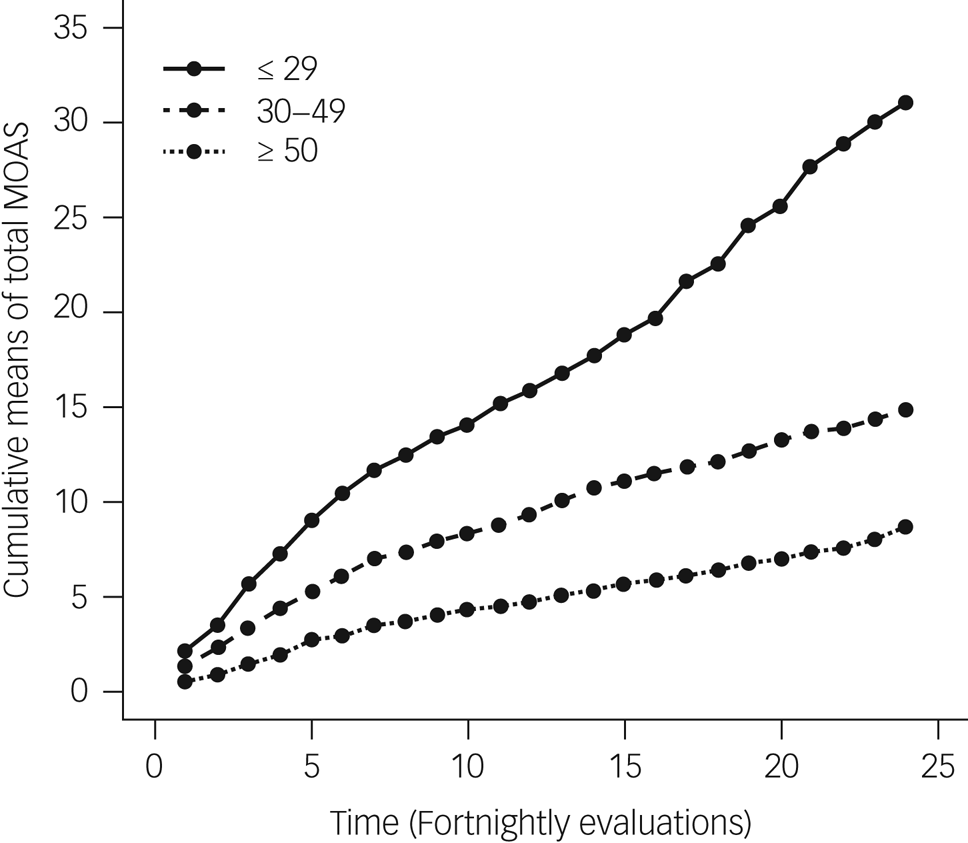

To evaluate the longitudinal pattern of violent behaviour (employing the cumulative means of total MOAS scores) according to age, three age groups were defined: 18–29 (n = 28), 30–49 (n = 202) and ≥50 years (n = 110). The cut-off thresholds were found employing four different smoothing techniques to evaluate the relationship between age and the AUC for the cumulative MOAS scores for each participant (see supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 2 shows the pattern of the cMOAS scores according to age category. Younger patients showed more overt aggression than older patients. The AUCs for the cMOAS scores of the three age groups were respectively 389, 214 and 111. It is interesting to note that the ratio between the AUCs for the first and second age groups (1.82) was quite similar to the ratio for the second and third age groups (1.92), indicating a sort of ‘linear trend’ in aggressive and violent behaviour associated with age. Among males the AUCs for the cMOAS scores for the three age groups were respectively 389, 214 and 111, and among females they were 401, 296, 34. Supplementary Fig. 2 shows the cMOAS pattern stratified by age groups separately for males and females.

Fig. 2 Cumulative means of total scores on the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS) in three age groups over time.

A cMOAS AUC = 0 was seen for only 2 out of the 28 participants between 18 and 29 years of age (7.1%) (they were males), about one-third (32.2%) of the 202 participants between 30 and 49 years of age (60 males and 5 females) and about half (49.1%) of the 110 participants over 49 years (42 males and 12 females). These three percentages were highly significantly different (χ2 = 19.7; P < 0.001), with a highly significant linear trend (P < 0.001). On the other hand, no difference was found when comparing the mean values of logarithmically transformed positive AUCs for the age groups (P = 0.224), even taking the effect of gender into account.

Generally, the pattern of cMOAS scores shown in Fig. 2 was replicated when the analysis was repeated within categories of selected variables (e.g. diagnosis, group, setting, SUD, medications); these patterns are shown in supplementary Figs 3–5. Numerically, older (≥50) participants always showed the lowest MOAS scores; the cMOAS pattern for younger participants (18–29) generally indicated the highest aggression.

Aggressive and violent behaviour and moderating variables

To evaluate whether the probability of not showing any aggressive or violent behaviour at all remained associated with age groups after having taken into account the effect of selected variables (e.g. diagnosis, group, setting, SUDs, medications), a logistic regression analysis was employed. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of various models fitted with logistic regressiona

LRT, likelihood-ratio test; SUD, substance use disorder.

a. The dependent variable is the probability of having a cumulative Modified Overt Aggression Scale score equal to zero. Raw refers to the model including only age as a categorical independent variable. The other rows show the ORs (together with associated 95% CIs) for the age category, adjusted for the variable indicated in column 1. The last row refers to the logistic model including age and the other six considered variables.

Older participants showed the highest probability of displaying no aggressive or violent behaviour at all, and younger participants showed the lowest, even after taking into account the joint effect of these selected variables. Both raw and adjusted odds ratios were quite similar and significantly different from 1 (the P-values of the likelihood-ratio test for the age effect, both raw and adjusted, were always highly significant and well below 0.001; Table 3). The odds of displaying no aggressive behaviour at all for participants ≥50 years old were about six times those for participants aged 30–49 and were about twelve times those for younger participants.

Discussion

It has been long known that violent behaviour is associated with a number of static risk factors, such as male gender and young age.Reference Kennedy, Burnett and Edmonds1,Reference Blair2,Reference Liu4–Reference Herrenkohl, Maguin, Hill, Hawkins, Abbott and Catalano6 Recent comprehensive reviews on the topic have confirmed the higher risk of aggressive and violent behaviour among males.Reference Whiting, Lichtenstein and Fazel40 Dynamic factors, such as impulsivity, risk-taking behaviour and SUD, also correlate with a higher risk of violent behaviour.Reference Blair2,Reference Chamorro, Bernardi, Potenza, Grant, Marsh and Wang10,Reference Whiting, Lennox and Fazel12,Reference Whiting, Lichtenstein and Fazel40–Reference Moulin, Palix, Golay, Dumais, Gholamrezaee and Azzola42 This study includes, to our knowledge, the longest follow-up of aggressive and violent behaviour, with participants monitored every 2 weeks with the MOAS.Reference de Girolamo, Bianconi, Boero, Carrà, Clerici, Ferla, Carpiniello, Vota and Mencacci43

In this study we found that during the 1-year follow-up of participants with severe mental disorders, those aged 18–29 years had a risk of violent behaviour 12 times higher than those aged 50–65 years old, and the odds ratio remained high, even controlling for other variables (e.g. gender, diagnosis, group, setting, SUD, medications).

Sociodemographic characteristics, such as being single and employed, and clinical features, such as a recent history of SUD, were also associated with young age.

Clinical correlates of aggressive and violent behaviour

In our sample of psychiatric patients, a high proportion of younger patients met diagnostic criteria for personality disorders as assessed using the SCID-II.Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams27,Reference First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams and Benjamin28 Impulsivity and risk-taking are prominent features of specific psychopathological conditions (e.g. externalising disorders, cluster B personality disorders and various types of antisocial behaviour).Reference Kennedy, Burnett and Edmonds1,Reference Grant, Stinson, Dawson, Chou, Ruan and Pickering9–Reference Nigg11,Reference Howard44 Individuals with antisocial personality disorder are also inclined to display interpersonal manipulation and low affectivity.Reference Candini, Ghisi, Bottesi, Ferrari, Bulgari and Iozzino45 In our study, we confirmed an association between these trait variables, although correlation coefficients were of limited size.

In our study, impulsivity, aggression and hostility rated on the BIS-11,Reference Barratt33 BGLHAReference Brown, Goodwin, Ballenger, Goyer and Major31 and BDHIReference Buss and Durkee32 also correlated negatively with adulthood: as age increased, there was a decrease in the ratings on these instruments. Several studiesReference Alcorn, Gowin, Green, Swann, Moeller and Lane46,Reference Barratt47 have shown that violent behaviour correlates positively with high levels of impulsivity and anger, variables that peak in adolescence and decrease with advancing age.Reference Chamorro, Bernardi, Potenza, Grant, Marsh and Wang10,Reference Steinberg14,Reference Galvan, Hare, Parra, Penn, Voss and Glover15

Anger, evaluated using the STAXI-2,Reference Margari, Matarazzo, Casacchia, Roncone, Dieci and Safran35 also decreased significantly with increasing age, confirming that younger age is associated with a higher level of anger. As some authors have shown,Reference Barratt47–Reference Candini, Ghisi, Bianconi, Bulgari, Carcione and Cavalera51 at least in people with psychotic disorders, anger might be the fundamental mediator between psychotic symptoms and the trigger of violent behaviour. Higher levels of anger, as detected with the STAXI-2, in young people and in people with personality disorders might be an extremely important therapeutic target: a reduction in anger might result in a reduction in the risk of aggressive and violent behaviour.

Aggressive and violent behaviour

We evaluated the frequency and severity of aggressive and violent behaviour with the MOAS.Reference Lawless and Nadeau36 Using a specific analytical methodology which made it possible to control the large number of MOAS ratings equal to 0, a linear increase in MOAS ratings was observed, especially in participants with a history of violence, who exhibited more aggressive and violent behaviour than those with no history of violence.Reference di Giacomo, Stefana, Candini, Bianconi, Canal and Clerici52

Then, to understand how age was associated with violent behaviour, the sample was divided into three age groups: 18–29, 30–49 and ≥50 years of age (Fig. 2). Within these three groups, there was a marked difference: among participants belonging to the first group (18–29 years), only 2 out of 28 showed an average MOAS score equal to zero, i.e. an absence of violence. On the other hand, one-third of the second group (30–49 year) and half of the fourth group (≥50 years) showed a total absence of violent and aggressive behaviour over 1 year, i.e. with increasing age, there is a greater likelihood of low levels of aggression and violence. These results were confirmed even controlling for the gender effect.

Clinical implications

These findings may have interesting clinical implications. Literature suggests that previous violent episodes are strongly associated with the risk of repeated violent episodes.Reference Grassi, Biancosino, Marmai, Kotrotsiou, Zanchi and Peron53 Thus, recognising anger and its determinants in young patients might be an important step for the development of preventive interventions aimed at the reduction of the risk of future violent behaviour.Reference Whiting, Lennox and Fazel12,Reference Volavka and Citrome54–Reference Strassnig, Nascimento, Deckler and Harvey56 Furthermore, the abundant literature on age at onset of mental disorders shows that most disorders have their onset in youth.Reference Volavka and Citrome57 Since the occurrence of violent behaviour can easily have serious legal, interpersonal, occupational and educational consequences, which may have long-lasting effects, the early and accurate recognition of the risk of violence should be a priority for mental health services. Specific psychotherapeutic interventions targeting anger and impulsivity may result in a lower risk of aggressive and violent acts in the future,Reference Volavka and Citrome57 ultimately improving the life of young patients. These clinical dimensions should also be taken into account for the prevention and treatment of SUDs, another modifiable risk factor closely associated with aggressiv and impulsivity.Reference Beck, Heinz and Heinz17,Reference Fazel, Långström, Hjern, Grann and Lichtenstein58

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. First, the duration of the observation period (1 year) may have reduced the possibility of detecting new aggressive and violent episodes and hence of identifying long-term predictors of such behaviour. Second, the MOAS assessment was based on the reports of patients’ treating clinicians or family members and not based on a direct 24 h observation. Thus, our results might have underestimated the occurrence of aggressive and violent behaviour in particular among out-patients, because the MOAS was not used to evaluate each individual aggressive episode. In any event, the restricted period of observation for each MOAS rating (2 weeks) makes it unlikely that relevant episodes of aggression or violence remained undetected, and the frequency of the MOAS ratings was the highest recorded so far in prospective cohort studies.Reference de Girolamo, Bianconi, Boero, Carrà, Clerici, Ferla, Carpiniello, Vota and Mencacci43 Finally, this study evaluated a psychiatric population, not a sample from the general population; therefore the findings might not apply to the general population.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1047.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following clinicians, who provided valuable help for the realisation of the project: Paola Artioli, MD, Silvia Astori, MD, Emanuele Barbieri, MSN, Annalisa Bergamini, MD, Francesca Bettini, MD, Monica Bonfiglio, MD, Silvia Bonomi, MD, Stefania Borghetti, MD, Giulia Brambilla, MD, Paolo Cacciani, MD, Pierluigi Castiglioni, MD, Giorgio Cerati, MD, Andrea Cesareni, MD, Ezio Cigognetti, MD, Fabio Consonni, MD, Marta Cricelli, ClinPsych, Alessia Delalio, MD, Giacomo Deste, MD, Emanuela Ferrari, MD, Giulia Gamba, MD, Silvio Lancini, MSEd, Assunta Martinazzoli, MD, Luca Micheletti, MD, Giuliana Mina, MD, Donato Morena, MD, Antonio Musazzi, MD, Paola Vittorina Negri, MD, Alessandra Ornaghi, MD, Roberta Paleari, MD, Ivano Panelli, MSN, Cristina Pedretti, MSN, Rosa Perrone, MD, Monica Petrachi, MD, Elisabetta Polotti, MD, Francesco Restaino, MD, Enrico Rossella, MD, Emilio Sacchetti, MD, Daniele Salvadori, MD, Jacopo Santambrogio, MD, Simona Scaramucci, MD, Pasquale Scognamiglio, MD, Giuseppina Secchi, MD, Joyce Severino, MD, Valentina Stanga, MD, Bruno Travasso, MD, Cesare Turrina, MD, Alessandra Vecchi, MD, Alessandra Zanolini, MSEd.

Author contributions

G.d.G., L.I., G.B., M.C., M.T.F., G.B.T. and A.V. designed the study. L.I., G.S., C.G. and L.Z. collected the data. R.M. and G.d.G. took primary responsibility for preparing the manuscript. L.C. contributed to the data analysis. All authors assisted with writing sections and with manuscript preparation. All authors approved the final manuscript for submission.

Funding

The VIORMED-2 (Violence Risk and Mental Disorder 2) project was funded by the Health Authority of Regione Lombardia, Italy (grant CUP E42I14000280002 for ‘Disturbi mentali gravi e rischio di violenza: uno studio prospettico in Lombardia’ with Decreto D.G. Salute no. 6848, 16 July 2014). The funder of the study had no role in design of this study, data collection, data analysis, writing of the report, or the decision to submit for publication.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.