Overview

When the twentieth century opened, Muslims, Christians, and Jews inhabited shared worlds in the region that stretches across North Africa and through western Asia. They held in common daily experiences, attitudes, and languages – even foods that they cooked and ate.1 They rubbed shoulders in villages, city neighborhoods, and apartment buildings, and crossed paths in shops and markets.2 In the history that this book examines – a history that goes roughly up to the start of World War I in 1914 – these contacts were on wide display.

The richness and depth of this shared history was no longer apparent as the twentieth century ended and the twenty-first century began. Indigenous or permanent resident communities of Jews and Christians had dwindled, following the impact of wars, decolonization movements, and the politics of the Arab-Israeli conflict, all of which propelled waves of migration. The Islamic societies of the Middle East were more solidly Muslim than ever before in history.

During the twentieth century, Jews dispersed almost completely from Arabic-speaking domains. By 2014, for example, the Jewish population of Egypt numbered just forty or so people3 – a steep drop for a community that, at its peak during the 1920s and 1930s, had included some 75,000–85,000 members, many with deep roots in the land of the Nile.4 In Libya, not a single Jew remained by 2000.5 In Turkey, whose territory was once a haven for Jews fleeing the Iberian peninsula in the wake of the Reconquista, just eighteen thousand remained in 2012.6 At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the largest Jewish population living within an Islamic polity may have been in Iran, a theocratic republic that justified its official tolerance for non-Muslims on readings of the Qur’an. Iranian government census data from 2012 only counted about nine thousand Jews, but outside observers estimated that Iran may have actually hosted a Jewish population that was closer to twenty-five thousand.7 The striking exception to this pattern of Jewish diminution was Israel, whose mid-twentieth-century creation provided a haven for Jews around the world but at the same time uprooted several hundred thousands of Arabic-speaking Muslims, together with a proportionally smaller number of Christians, who became known as Palestinians.8

During the twentieth century, Middle Eastern Christian populations also diminished. In Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria, historic Christian communities persisted but dwindled as a proportion of the population.9 A dramatic version of this shrinkage occurred in the territory that became the British mandate of Palestine, where in 1900 Christians had comprised perhaps 16 percent of the population. A century later they accounted for less than 2 percent in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza – a demographic shift that resulted from voluntary migration, displacement, and probably also lower birthrates.10 Twentieth-century change was even more extreme in Anatolia, a territory that belonged to the Ottoman Empire until the empire’s demise after World War I, but then became the heart of the Republic of Turkey. Approximately two million Christian Armenians were living in Anatolia in 1915, when Muslim Turks, Kurds, and muhajirs (the latter Muslim refugees from Russian imperial expansion in the Caucasus) carried out a series of massacres and forced marches that nearly annihilated them.11 Today, only about sixty thousand Armenians remain in Turkey as citizens, while the Turkish population as a whole is 99 percent Muslim.12

As the twenty-first century opened, many Christian churches, monasteries, and other landmarks – in Israel, the West Bank of Palestine, Turkey, and parts of Jordan – had lost the local Christian populations that once sustained them. One scholar remarked that these Christian sites ran the risk of becoming theme parks for Western tourists, and thereby cash cows for Middle Eastern governments eager to boost their tourist revenues.13 In Syria and Iraq, meanwhile, civil wars prompted Christians to flee abroad disproportionately even as one-third of Syrians – Muslims and Christians alike – became refugees by 2016.14 And while economically motivated migration from Asia and Africa added diversity to Middle Eastern populations (with workers from Muslim, Christian, Hindu, Buddhist, and other backgrounds arriving in countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Israel), migrants tended to be short-term guest workers.15 Throughout the Middle East, permanent resident and citizen populations had become more homogeneous in religion.

Locally rooted Jewish populations have vanished throughout most of the Middle East, vast numbers of Muslim Palestinians have lost their place in the “Holy Land,” and Christians in the region have experienced an attrition that one observer called a “never-ending exodus.”16 So then why bother to tell a history of contact among Muslims, Christians, and Jews as this book does, by studying the Middle East before World War I? Why focus on community – even comity – rather than on conflict, rupture, and trauma?

Looking back on the expanse of Islamic history, many historians have argued that Islamic states, with few exceptions across the centuries, tolerated cultural diversity and promoted stability so that Muslims, Christians, and Jews were able to persist, coexist, and often flourish together. Islamic civilization, thus understood, was a collaborative and amicable enterprise. Other historians, however, have emphasized violence and tyranny as leitmotifs of Islamic statehood, arguing that non-Muslims fared especially badly during long periods of political decline, however one dates them. In interpretations of the twentieth century, an emphasis on repression persisted, with critics pointing to cases such as the Armenian massacres (1915), the Arab-Israeli conflict (1948–present), and the Lebanese Civil War (1975–c. 1990) to emphasize a Middle Eastern propensity for a kind of political violence that drew on religious antipathies.

The long history of intercommunal relations in the Islamic Middle East may never have seen a “golden age,” but neither was it a saga of perpetual crisis. A sober look at history suggests that, in most times and places, relations between communities were, as one might say in colloquial Egyptian Arabic, kwayyis (“pretty good” or “okay”); Muslims, Christians, and Jews simply persisted in proximity. Daily lives were the sum of getting by – the quotidian with an admixture of tension and rapport. When the twenty-first century started, this picture of the unsensational in Middle Eastern intercommunal relations did not prevail in Europe and North America. Instead, the more common notion was that the history of intercommunal relations in the Middle East reflected what one may call a “banality of violence,” with routine, even absentminded, religious conflict assumed as the normal way of life.17

In an essay collection titled Imaginary Homelands, the novelist Salman Rushdie (b. 1947) suggested not only that “description is itself a political act” but also that “redescribing a world is the necessary first step towards changing it.”18 Certainly redescribing a lapsed world may offer a way of living with the past, in the sense of putting up with it, recovering from it, and coming to terms through a modus vivendi. This redescribing involves choice and selection – what the philosopher Paul Ricoeur characterized as an active searching for the past, a going out and doing something, in the perpetual sifting of history for meaning.19

In sifting through the past, this book offers an alternative to the “banal violence” interpretation of the Middle East by reclaiming the history of the mundane in social contacts that wove the fabric of everyday life. It analyzes the complex roles of religion within Middle Eastern societies. And it studies the tension between individuals and collectives vis-à-vis religious identity. There are two reasons for focusing on this tension. First, people are quirky, so that what one Muslim, Christian, or Jewish person did in a particular place or time may not have typified Muslim, Christian, or Jewish behavior collectively. Second, and increasingly in the modern era, Islamic states in the region struggled to classify and treat people as members of religious collectives, in accordance with Islamic law and tradition, while respecting the needs, responsibilities, and aspirations of people when they were thinking, speaking, and acting on their own, as individuals.

I will now elaborate on the idea of the history of the mundane and consider the spatial scope and timescale for this study. After explaining the book’s approaches and assumptions, I will present the book’s arguments in a nutshell.

Picturing the Mundane

Sometime around 1900, a chocolate company called D’Aiguebelle, operated by Trappist monks in Drôme (southern France), published a series of chromolithographic cards with explanatory texts on their backs. These purported to show and tell the story of Turkish, Kurdish, and Circassian atrocities perpetrated against Greeks and Armenians in the 1890s.20 If the images alone failed to convey the story of Muslim-Christian conflict, then the captions on the reverse were explicit. One card shows the “Pillage of the Monastery of Hassankale and the Murder of the Patriarch”: there in the picture rests the patriarch, at that moment still living but fallen and bloodied near the altar, as Muslims carry off loot. The caption on the reverse explains that on November 28, 1895, “Musulman” marauders burned, pillaged, and murdered their way through the district where the monastery was located; the marauders spared only three villages out of forty, and forced survivors to convert to Islam. Equally evocative from D’Aiguebelle’s chocolate cards are those illustrating the decapitation of Greek insurgents in Crete, the dragging of Armenian corpses through the streets of Galata in Istanbul, and the sale of Armenian captives as slaves. The last two cards presented atrocities against Armenians twenty years before the events of 1915, which survivors and their heirs later remembered as the Armenian Genocide.

Image 1 Massacres d’Arménie: Arméniens égorgés à Ak-Hissar, c. 1895–96, by Chocolaterie d’Aiguebelle (Drôme, France). Chromolithographic chocolate card. Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Caption on the reverse states that the image depicts Armenians massacred by Circassians in the market at Ak-Hissar, in the Vilayet of Ismidt, on October 3, 1895.

How did these particular images shape public opinion among French chocolate lovers in the late 1890s – people who came to possess chocolate cards depicting bucolic scenes, masterpieces of medieval Christian art, French monarchs and their castles, maps of the French Empire, and so forth?21 For the person nibbling on chocolate, and considering the cards that came in its wrappers, the images may have reinforced the notion that in the Ottoman Islamic world, outrageous sectarian violence between Muslims and Christians was common to the point of mundane. These cards, which as a “democratic art” were items that many schoolchildren collected and traded,22 broadcast news in western Europe about grim conditions for Christian Greeks and Armenians farther east. (Certainly the D’Aiguebelle monks regarded them as vehicles for promoting a “Christian conscience” and social “catechism,” particularly among children, who were their target audience.23) Like the French picture postcards of the same period, which presented studio-staged fantasy portraits of seminaked (but still head-veiled) Algerian Muslim women, these D’Aiguebelle chocolate cards advanced fantasies and stereotypes about the peoples of the “Orient.”24 As humble as they were, the chocolate cards wielded power and contributed to the waging of discursive wars that recall the social critic Susan Sontag’s famous essay on photography, the “ethics of seeing,” and the role of the shooting camera as a weapon.25

If anything, popular European and North American associations of the Middle East with banal religious violence have become stronger than they were a century ago, as a quick survey can show. In 1993, the political scientist Samuel T. Huntington (1927–2008) published an article in the journal Foreign Affairs, in which he speculated on global trends in the post–Cold War era. “World politics is entering a new phase,” he claimed. Henceforth, among humankind, “the dominating source of conflict will be cultural ... [and] will occur between nations and groups of different civilizations.” Huntington foresaw a “clash of civilizations” in which some would be more prone to violence than others. He predicted special problems “along the boundaries of the crescent-shaped Islamic bloc of nations from the bulge of Africa to central Asia,” and concluded, “Islam has bloody borders.”26 Huntington was not the first to describe a “clash of civilizations” between a “Christian West” and “Islamic East.”27 Certainly his portrayal of Islam’s “bloody borders” tapped into a deep discursive history that stretched at least as far back as 1095, when the Roman Catholic pope, Urban II (1042–99), issued his call for a crusade. Nevertheless, the “clash of civilizations” became Huntington’s trademark, while ensuing events led many observers in news outlets and blogs to describe his prognosis as “prophetic” (as even the most casual internet search makes abundantly clear).

In the 1990s, around the time that Huntington published his article, Sunni Muslim extremist groups were becoming increasingly strident in their endorsement and pursuit of violent jihad. Some of these groups, consisting of Bosnian Muslim fighters and Arab Muslim volunteers, had begun to prove their mettle in the Balkan or Yugoslav Wars (1991–c. 2001), which sharpened regional, ethnic, and religious lines of distinction.28 In 1998, Osama bin Laden (1957–2011) tried to stake out a leadership position at the forefront of international jihadists, by declaring a “World Islamic Front” dedicated to “jihad against Jews and Crusaders.” It was the duty of every Muslim everywhere, bin Laden asserted, “to kill the Americans and their allies – civilians and military – ... in any country in which it is possible to do it.”29 The goal, he declared, was to liberate Jerusalem’s al-Aqsa mosque (and by extension, the land of Palestine from Israeli Jewish control) and the Great Mosque of Mecca. The latter goal contained an oblique reference either to American troops, who had arrived in Saudi territory in the wake of Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, or to the ruling house of Sa’ud, which controlled the holy sites of early Islam in western Arabia.

The subsequent terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, exceeded the worst expectations of the most pessimistic political analysts. In the wake of this tragedy, American scholars produced a vast literature on the themes of “what we did wrong” (entailing a critique of Western imperialism and cultural hegemony in the Middle East), “where they went wrong” (suggesting a generalized Muslim failure to construct stable and progressive Islamic societies in the modern age), and “what Islam really is” (attempting to dismantle popular stereotypes among non-Muslims that have associated Islam with terrorism and violence).30 Meanwhile, bin Laden’s “world front” expanded but atomized, and developed “franchises,” to use the commonly invoked marketing term that made Al-Qaeda sound like a fast-food chain. Al-Qaeda’s ostensible affiliates went on to stage attacks on civilians in a variety of places and venues: a synagogue in Tunisia (2002), a nightclub in Bali (2002), subways in Madrid (2004), and London (2005), and more.

In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, the US government and some of its allies launched wars in Afghanistan (Al-Qaeda’s training ground) and Iraq (where 9/11 offered a pretext for unseating a brutal dictator who had played no role in the attacks). The US invasion of Iraq triggered, in turn, an Iraqi civil war, as ethnic and sectarian groups and factions jockeyed for power. In the seven years following the US invasion, many Iraqi civilians died amidst violence – perhaps one hundred thousand people31 – the vast majority of them Muslims (representing both the Sunni and Shi’i sects of Islam). Unknown numbers died or led diminished lives as a result of the auxiliary phenomena of war, such as damaged medical infrastructures and psychological traumas.

During the first decade of the twenty-first century, western Europe witnessed a rising tide of Islamophobia and anti-Muslim-immigrant sentiment as some politicians and pundits questioned the ability of immigrants to assimilate into liberal host societies. Among questions asked were these: Could a woman wear a burka or niqab, thus covering her face, and still be French? What about a girl in a French government school? And if such a female was not French-born, was she worthy of receiving citizenship in France? (In a case that received considerable attention in 2008, the French government answered this last question with a “non.”32) An even more sensational episode occurred in Denmark in 2005, when a newspaper published a set of editorial cartoons lampooning the Prophet Muhammad. Many Muslims around the world took grave offense and staged protests. But many Danes, non-Muslims, and liberal Muslims took offense, too, resenting efforts to curb free expression, and viewing protests as another iteration of banal violence by Muslim conservatives.33 In early 2015, local militants claiming an affiliation with a Yemeni branch of Al-Qaeda staged an attack in Paris on the French newspaper Charlie Hebdo, which had also published satirical portrayals of the Prophet Muhammad and Islam, and in a coordinated attack, slaughtered shoppers at a kosher grocery in the city. These events confirmed popular fears in the West about Muslim anti-Jewish sentiment and suppression of free speech, while seeding anti-Muslim xenophobia.

Other crises that appeared to have some religious dimension – for example, between the Israeli government and the Palestinians, between the Russian government and Chechens in Chechnya – persisted in the background, riveting Muslim viewers throughout the world via satellite television.34 Meanwhile, amidst the Syrian Civil War which erupted in 2011, a jihadist insurgency group, which had already established a foothold in Iraq after the US invasion of 2003, seized control over parts of Syria after that country’s descent into chaos. Outsiders tended to call this entity by various acronyms, such as ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) and Da’ish (based on the acronym of the group’s name in Arabic). Claiming to lead a revived caliphate in the parts of Syria and Iraq that it controlled, supporters of this group engaged in egregious acts of violence against Muslim opponents, Christians, Jews, Yezidis, and others, and spawned copycat affiliates in places like Libya. Meanwhile, Da’ish sympathizers in western Europe perpetrated outrageous acts of mass murder, killing scores in Paris and Brussels during attacks in 2015 and 2016 that targeted people in cafés, a music hall, an airport and metro station, and other venues of everyday life.

New violence, meanwhile, begat memories of old violence. In 2013, as one of his first deeds as pope of the Roman Catholic Church, Francis (born 1936 as Jorge Mario Bergoglio) canonized the 813 “martyrs of Otranto” who had reportedly died at the hands of Ottoman forces in 1480 when they refused to convert to Islam. In doing so, he completed the canonization process that his immediate predecessor, Benedict XIV, had started, building, in turn, upon an initiative that Pope Clement XIV had opened in 1771.35 The canonization of the Otranto martyrs suggested the importance of persistent memories of jihads, crusades, and mutual martyrdom in imagined, and continually reconfigured, histories of Muslim-Christian relations.

Conflict between communities in the Middle East is easy to imagine when stories and images of animosity abound in books, on the news, and in other popular media. But what does it look like for communities to share history, and to spend decades in a state of proximity characterized by relative quiet? What method can one use to gain access to the un-sensational, the un-newsworthy, and the day-to-day familiar, before capturing it in words?

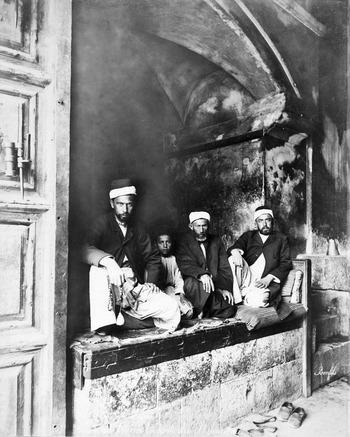

The method used here is to draw not only on history books, but also memoirs, cookbooks, novels, anthologies, ethnographies, films, and musical recordings, which can offer insights into cultures of contact. However impressionistically, such sources can yield insights into the history and anthropology of the senses – the sounds, tastes, touches, and smells that have added up to shared experience.36 One can find evidence for contact and affinity, for example, in shared Arabic songs and stories, sung or recounted by Muslims, Christians, and Jews;37 in the remembered smell of jasmine blossoms, threaded and sold on strings after dusk; in “recollections of food” that “have been wedged into the emotional landscape,”38 like a particular bread sold on street carts during Ramadan;39 even affection for the same bumps in the road (a sentiment that one young Jewish woman expressed to a documentary filmmaker, as she moved through Tehran in a car).40 Then, too, there are common sights, spaces, and places – rivers, monuments, landmarks, humble abodes, cafés. From the nineteenth century, photographs and film media appear as well to “thicken the environment we recognize as modern.”41 Photographs can remind us of what we may otherwise forget: for example, the long history of Muslim custodianship in caring for and protecting the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (built on the site in Jerusalem where Jesus was reportedly crucified). Indeed, a photograph from the well-known, late nineteenth-century French firm, Maison Bonfils, captured such an image for posterity, by showing three Muslim men and a boy resting in a niche at this church’s entrance.42

Image 2 “Guard turc à la porte de St. Sepulchre” (Turkish Guard at the Gate of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem), c. 1885–1901, Bonfils Collection, Image Number 165914.

The Middle East: Pinning Down a Slippery “Where”

This book seeks to tell the history of intercommunal relations in the Middle East during the modern period up to World War I. But in fact, the terms “Middle East” and “modern” are both very slippery, so that scholars over the years have been debating – and changing their minds about – what they mean.

Among English speakers, the “Middle East” has been more of an idea than a fixed place, and the region associated with the term has shifted. In 1902, an American naval historian and evangelical Christian named Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840–1914) – a man who believed in the “divinely imposed duties of governments”43 – coined the term “Middle East” to suggest the area stretching from the Arabian Peninsula and the Persian Gulf eastward to the fringes of Pakistan. Mahan intended the “Middle East” to complement rather than replace the extant term “Near East,” which in his day suggested the region from the Balkans and Asia Minor to the eastern Mediterranean. After World War I, however, the term “Middle East” gained momentum, until by World War II it was displacing “Near East” for current affairs.44

Reflecting larger geopolitical trends, some places that English speakers had once deemed “Near Eastern” did not make the transition to “Middle Eastern” in the mid-twentieth century. Thus during the Cold War era of the early 1950s, the US government’s Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) reclassified Greece and Turkey (which had joined the Council of Europe a few years earlier) as “European” rather than “Near Eastern” for purposes of its analysis.45 (Their reclassification points, of course, to the fact that “Europe” has also been notoriously slippery as an idea.46) At the same time, other areas – notably the Arabic-speaking countries of North Africa as far west as Morocco – became more closely associated with the “Middle East” for purposes of the CIA’s intelligence gathering. The foundation of the Arab League in 1945, and its subsequent development and expansion in membership, also strengthened the links between al-Maghrib and al-Mashriq, meaning the western and eastern halves of the Arabic-speaking world.

Bearing this somewhat complicated history of regional naming in mind, readers should understand that when this book uses the term “Middle East” to refer to an area stretching from Morocco to Iran, and from Turkey to Yemen, it does so for convenience. There is, of course, some historical rationale for identifying a region along these lines. Except for Turkey and Iran, all of the countries thus covered have had significant Arabic-speaking communities; except for Morocco and Iran, all were once claimed by the Ottoman Empire (even if the extent of Ottoman control varied greatly in practice). Except for Turkey, all were among the early heartlands of Islamic civilization, having become part of the Islamic empire that emerged within a century of the death of the Prophet Muhammad (c. 570–632 ce). Two centuries ago, moreover, this “Middle Eastern” region had small but significant Jewish communities dotting its landscapes (and particularly its urban landscapes), while outside the Maghreb and Arabia, the region hosted substantial indigenous Christian communities as well.

By the early seventeenth century, one empire claimed most of the territory that constitutes the Middle East of the present-day imagination: this, again, was the Ottoman Empire. Having originated around the year 1300 in what is now western Turkey, the Ottoman Empire claimed its oldest and most populous territories in southeastern Europe. The Ottoman Empire therefore began as more of a European empire than a Middle Eastern one, at least until the nineteenth century, when territorial losses in the Balkans tilted the empire’s focus toward the Arab world. After its conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the Ottoman Empire devised distinctive and fairly consistent policies for administering the Muslim, Christian, and Jewish communities in its domains, and these policies left their marks on the countries that emerged in the wake of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I.47 To repeat a point worth emphasizing, the Ottoman Empire never managed to conquer either Iran or Morocco, two places that were not only countries but, in many periods, empires and even ideas (just as the Middle East is an “idea”) in their own right. In the course of their histories, Iran and Morocco evinced their own distinctive policies and practices toward Muslims, Christians, and Jews.

In this book, I focus on the Ottoman Empire, while mentioning Morocco and Iran only occasionally, in a comparative context. There are two reasons for this choice. First, the relative coherence of Ottoman policies toward Muslim, Christian, and Jewish peoples makes the Ottoman Middle East a practical unit for study. Second, I am writing this book under constraints of length. Although there would be enough material on the subject at hand to fill a multi-volume encyclopedia, the goal here is to examine the contours and sweep of a rich history within a single readable volume.

The Modern Era: Pinning Down a Slippery “When”

The timeframe of this book requires explanation. I begin my survey in the seventh century, at the moment when Islam and Muslims appear on the world stage, although I focus primarily on the modern period after approximately 1700. Readers should know that deciding when to start the history of the “modern” Middle East is a tricky business. A generation ago, most historians of the Middle East hailed 1800 as a rough starting point for the modern period, but scholars today are more inclined to look deeper into the past. These debates over the timing of the “modern” Middle East arise from questions that are relevant to world history at large. If we assume that modernity “happened” in different places at different times, then what was it exactly: a state of mind; a set of accomplishments; a condition? How did it begin; that is, what or who started it? Did it emerge at definable moments, or did it just creep up? And what did modernity look or feel like both from the outside and to those who were living it?

Some scholars see modernity as an economic phenomenon: the product of an accelerating global trade in raw and finished materials, of capitalist accumulation, and of new patterns of mass consumption. But modernity’s humanistic and cultural manifestations are just as striking. Notably, modernity entailed a new kind of individualism relative to extended families and larger communities, expressed, for example, through the individual accumulation of wealth, the individual use of new technologies and its products (such as printed books, used for silent, solo reading48), and the individual consumption of goods (such as coffee – particularly when bought as personal, brewed cups in a coffeehouse, as opposed to as beans for the family coffeepot). The shift to this kind of individualistic behavior, which one can trace in Ottoman domains from at least 1700, if not earlier, allowed for new forms of social mobility and thereby challenged or overturned established social conventions and hierarchies. By the nineteenth century this shift was also leading to contradictions in government policies. For, on the one hand, the Ottoman state was beginning to conceive of its subjects sometimes as individuals (e.g., theoretically endowed with a freedom of conscience, or individually liable for taxation or military conscription). But, on the other hand, it was continuing to classify and treat them as members of older collectives, and above all, as members of religious communities of Muslims, Christians, and Jews. This tension between older state policies toward people as members of collectives and the newer, albeit uneven, recognition of people as individuals was a part and parcel of modernity.

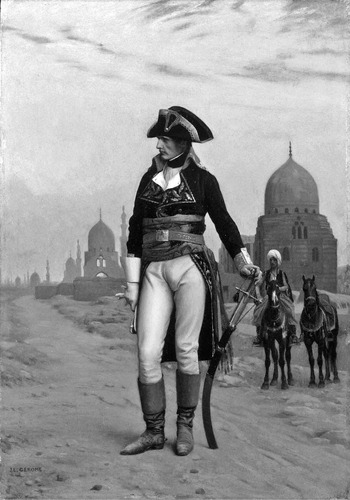

A generation ago, many historians and literary scholars in Europe and North America pointed to 1798 as a particularly significant “moment” for the advent of modernity in the Arabic-speaking world. This was when French troops, led by Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821), invaded Egypt and held the country for a rocky three years – just long enough to overturn local power structures and to introduce new ideas, practices, and technologies in ways that had substantial long-term consequences.49 Leading scholars no longer regard the Napoleonic conquest of Egypt as the trigger for modern Middle Eastern history,50 but in retrospect the conquest retains symbolic import anyway – if only because it so vividly points to dramatic changes that were afoot.

Image 3 Napoleon in Egypt, 1867–68. Oil on wood panel, 35.8 x 25.0 cm. Princeton University Art Museum. Museum purchase, John Maclean Magie, Class of 1892, and Gertrude Magie Fund. Year 1953–78.

Consider, for example, how Napoleon brought Egypt its first Arabic moveable-type printing press, which he had stolen from the Vatican. Partly because of the introduction of this press, which in turn seeded the development of a local Arabic periodical culture and later of a government-sponsored translation enterprise from European languages into Arabic, historians of an earlier generation celebrated 1798 as the starting point for “modern” Arabic literature, as well as for a “liberal age” of Arab social, cultural, and political thought that eventually seeded forms of nationalism.51 Napoleon’s printing press definitely helped to stimulate the expansion of Arabic reading, writing, and literacy – just as Johannes Gutenberg’s moveable-type press, which made its debut in Mainz, in what is now Germany, in 1454, had done in Western Europe three centuries before.52

Even while acknowledging the tremendous significance of printing for modern cultures and politics, it would still be too much to say that Napoleon inaugurated modernity by introducing the Arabic printing press. For, indeed, Arabic printed works were known long before Napoleon – as early as 1633 – when the Propaganda Fide (the missionary wing of the Roman Catholic Church) first published an Arabic grammar amidst new efforts to appeal to Middle Eastern Christians. Soon other Catholic printed works appeared in Arabic, too. And while this literature appealed to a small Christian, educated, church-centered elite, its readership was growing, as attested by the brisk trade in printed Arabic books that monks from Shuwayr, in Mount Lebanon, began exporting to cities like Beirut, Damascus, and Cairo, during the second half of the eighteenth century – decades before Napoleon appeared on the scene.53

The same “Napoleon effect,” as one may call this attribution of impact, also obscured the Arabic literary production of Muslims. Until a generation ago, many scholars of Arabic literature (both within and outside the Arab world) celebrated 1798 as the start of a new literary era, while ignoring much of what came before it. Many scholars, indeed, shunted the Arabic literary production of 550 years – the period from the Mongol conquest of Baghdad in 1258 until the Napoleonic conquest of Egypt – into a black hole that they called the “Age of Decadence” (‘asr al-inhitat), implying an era of decline and torpor when nothing much happened. The work of rediscovering and reappraising the Arabic literary output of the eighteenth century (and indeed, of the seventeenth century) is only just beginning.54

What Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt did do, however, was to exemplify the stronger assertion of European imperial might that was occurring within the lands of the Ottoman Empire as the eighteenth century turned to the nineteenth. Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt proved to be one among many more military incursions to come – such as the British, French, and Russian entry into the Greek war for independence from the Ottomans during the 1820s, and the French invasion of Algeria in 1830. There were European economic incursions as well, though these became more manifest during the latter half of nineteenth century, when European countries or individuals gained monopoly concessions over raw materials, services, and transit routes – such as the Suez Canal. In different parts of the Middle East, the Western imperial push into the heartlands of the Islamic world facilitated, accompanied, or followed the arrival of European and American Christian missionaries, Jewish activists (representing organizations like the French Alliance Israélite Universelle), and eventually, in Jerusalem and its “Holy Land” environs, Christian and (much more significantly in the long run) Jewish settlers. Ideas about restoration to, and of, the lands of the Bible inspired these settlers and seeded the ideas and ideology that became known as Zionism.

The encroachment of foreign European imperialism (as opposed to domestic Ottoman imperialism in places like Greece and Bulgaria) put Ottoman authorities on the defensive, and prompted nineteenth-century Ottoman sultans to declare reforms in educational, military, and legal affairs. As the nineteenth century ended, too, Muslim thinkers began to formulate new ideologies of Muslim unity, Islamic revival, and nationalism. All of these developments, which had major consequences for the history of Middle Eastern communities, added strains to the mutual relations between local Muslims, Christians, and Jews, particularly as Christians and Jews began to more closely identify with – or to be perceived as identifying with – the languages, economies, values, and interests of foreign powers.

The bottom line is simple: Napoleon did not inaugurate Middle Eastern modernity, which helps to explain why this study looks to 1700, rather than 1800, as a rough starting point for “modern” Middle Eastern history. Nevertheless, because of his conquest of Egypt, Napoleon manages even now, almost two centuries after his death, to embody the kind of foreign influence and intervention that simultaneously alienated and enchanted people in Ottoman lands.

End dates are just as important as start dates to the construction of a story. This book wraps up its story in the decade after the Young Turks Revolution of 1908, when the Ottoman Empire still appeared to have the potential for durability in the twentieth century, and when World War I was just beginning.

The pre–World War I history covered in this book remains very relevant to our world today. The post-Ottoman states of the Middle East and North Africa – that is, states that emerged in territories that the Ottoman Empire had once controlled – did not break sharply from inherited traditions of Islamic and Ottoman statecraft. Nor were mid- to late-twentieth-century states such as Egypt, Syria, Iraq, and Algeria ever as secular as some of their proponents and critics once claimed – or as their own socialist or “nonaligned” (Cold War–era) rhetoric once made them seem on the international stage. In many respects, on the contrary, Islamic state traditions (which include laws of personal status) have carried on to today. Many old attitudes and expectations have also persisted, and these have continued to influence behaviors.

Approach and Assumptions

Traditional approaches to the history of intercommunal relations in the Middle East have either posited primordial, large-scale corporate identities (Muslims, Christians, Jews) or have emphasized the heterogeneity within communities. In both approaches, interconnectedness and overlap between the units of analysis have figured prominently. However, the usefulness of these approaches depends on the issue one is trying to understand. At a certain scale of analysis, there is such a thing as a “Muslim,” a “Christian,” and a “Jew,” and it makes sense to employ these as key concepts. But if one looks closely for fine details, then the categories become much fuzzier. One sees, for example, myriad distinctions among Muslims, Christians, and Jews with regard to ethnicity, sect, economic stature, and the like, and these often have a more important function on the ground than ostensible membership in a religious community. Likewise, there are vagaries of time and circumstance. Thus, a social category that is relevant to either a long-duration or abstract analysis may not be so relevant in analyzing relations among neighbors, in practice, during a particular historical moment.

In narrating history, this book starts from five main assumptions. First, Islamic civilization in the Middle East was not produced only by and for Muslims. Islamic civilization was a big house. Muslims, Christians, Jews, and others built it and took shelter, even as they created distinct Muslim, Christian, and Jewish cultures within it.55 Yet while Muslims, Christians, and Jews had distinctive cultures, they did not live in social oases. The challenge for the historian is to examine where their cultures intersected, and where they did not.

Second, Muslim, Christian, and Jewish populations in the Middle East historically exhibited considerable internal diversity in religious doctrines and practices. Although Muslims, Christians, and Jews sometimes embraced the idea of religious solidarity – with Muslims imagining an “umma,” Christians “Christendom,” and Jews common “Jewry” – divisions within each of these three groups were often pronounced and fraught with tensions. Among Muslims, for example, there were those we now call Sunnis and Shi’is, while diversity in custom and belief prevailed among Sunnis and among Shi’is as well. Among Christians, there were divisions between various Eastern or Orthodox churches and newer Catholic and Protestant churches. Among Jews, there were differences among Sephardic, Mizrahi, and Karaite Jews, and later among immigrant Ashkenazis.56 These “cultures of sectarianism”57 shaped perceptions and affected relations both among and between Muslims, Christians, and Jews.

Third, just as Middle Eastern societies were never monolithic, so intercommunal and intersectarian relations were never static. On the contrary, communities and individuals responded to ever-changing circumstances that reflected broader local, regional, and global trends. Population movements, shifting trade routes, new technologies, and wars – these developments and others affected how communities lived and how different groups in society fared and related to each other. Beirut in 1860 differed substantially from Beirut in 1900; Cairo differed from Fez or Algiers; life in remote villages was unlike life in big cities; the list goes on. For scholars of the modern Middle East, recognition of such variability is essential for dealing with the baggage of Orientalism, a series of “Western” discourses about the “East” that have emphasized the monolithically exotic and tyrannical nature of Islamic societies, along with their need for rescue or uplift.58

Fourth, religious affinity intersected with other variables – including language, ethnicity, gender, profession, social status, and affinity to place – to make individual and communal identities. Religion was only one variable – and not necessarily the most important – in determining how groups and individuals behaved. This last point presents the historian with looming questions for which there are no easy answers. When does it make sense, for example, to describe someone as a “Muslim” rather than as a “Kurd” or a “peasant,” as a “Jew” rather than a “merchant” or man of Damascus, or as a “Christian” rather than a poor widow? The question becomes more complicated and more pressing still when violence assumes a “religious idiom.”59 For example, to what extent is it accurate and fair to describe the Armenian massacres of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as “religious” conflicts, given that the Armenians happened to be Christians while their attackers, who spoke Turkish, Kurdish, and other languages, happened to be Muslims? Territorially rooted ideas about nationalism and citizenship, which grew more important as the twentieth century opened and advanced, add yet another factor to the equation of communal identities, by challenging the historian to consider, for example, the possibility of “Turkish” and “Syrian” collectives.

Fifth and finally, “religion” itself is a murky concept, more like a fog than like a fixed and sturdy box. The same is true of the adjective “religious.” As one historian of the ancient Mediterranean world observed in an analytical critique of these concepts, “The very idea of ‘being religious’ requires a companion notion of what it would mean to be ‘not religious’,” while the concept of religion, as it developed in modern European history, has often rested on the premise of its relative distinction from other spheres like science, politics, and economics.60 The reality is that ordinary people in the Middle East – like ordinary people everywhere, Europe included – were (and still are!) likely to fold invocations of the divine or concerns about life, death, destiny, and so on into the most ordinary everyday matters. To take one small example from early Islamic history, consider a letter that a Jewish merchant in Sicily wrote in Arabic in 1094, griping to his partner in Egypt about the latter’s decision to buy low-quality peppercorns without consulting him.61 If this spice merchant dropped God’s name into the argument, to dignify the exchange or signal honorable intentions, would that have made the document automatically “religious”? If we answer yes, then we are likely to find religion everywhere and nowhere. (Note that the guardians of the synagogue near Cairo who saved this particular letter centuries ago appeared to feel that its potential reference to God made it worthy of reverential treatment, or perhaps we would now say, made it “religious.”62)

Some of the most difficult questions to grapple with are these: What was religion and how did it matter – or not matter – in everyday lives? When did religious identity (based on adherence to a creed or identification with an associated group or sect) matter more than other forms of identity in motivating individuals or propelling events? How ethical is it for historians to assume (and thereby in some sense impose) identities, of a religious nature or otherwise, in describing individuals and groups? To what extent can the historian speak of common “Christian,” “Jewish,” and “Muslim” experiences, given that communities – and individuals – were so complicated? What about subsidiary or divergent communities and identities, for example, among Greek Orthodox, Shi’i, Sephardi, Yezidi, and other people? And how is it possible to pin down a narrative of Muslim, Christian, and Jewish relations considering that circumstances varied by time and place, and that evidence for day-to-day interactions is often scattered and anecdotal? This book grapples with these questions by emphasizing, rather than eliding, the complexities within the history, and by emphasizing the remarkable and ever-evolving variety of Muslim, Christian, and Jewish cultures that persisted side by side.

Many theologians and scholars of comparative religion now use the term “Abrahamic religions” to suggest historical genealogies connecting Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. The term signals the common recognition, among adherents of these three faiths, of the patriarch Abraham and his legacies, especially regarding belief in a single god (monotheism). Some scholars have used the term to suggest the potential for Muslim, Christian, and Jewish solidarity, or interfaith cordiality through scriptural and theological affinities.63 Others, by contrast, have pointed to the importance of “Abrahamic kinship” for asserting Muslim, Christian, or Jewish singularity with reference to the other two in the triad, that is, by sharpening family rivalries in ways that have translated during the past century into scripturally based land claims in Israel and Palestine.64 Since this book is not a study of comparative theology, it does not use “Abrahamic religions” as an analytical device. Instead, the book focuses on what men, women, and children have done – on social lives rather than religious dogmas. It explores the warts-and-all history of real people who lived in challenging times, as opposed to what scriptures, theologians, and other religious authorities have told them to do, while questioning the invocation or imagination of religious identity in policies and behaviors.

Five chapters and an epilogue follow. Chapter 2 traces the formation of early Islamic society and the elaboration of policies toward Christians and Jews. These policies went on to shape the policies and ideologies of many Islamic states as they emerged in different places and periods. Chapter 3 examines the Ottoman Empire, its modes of managing religious diversity (including its so-called millet system), and the accelerating social changes of the eighteenth century. Chapter 4 studies the nineteenth-century period of Ottoman reform, the efforts of Ottoman sultans and statesmen to promote a new understanding of what it meant to be an Ottoman subject, and the reception of their attempts. Chapters 5 and 6 focus on the decisive reign of Sultan Abdulhamid II, who emphasized the Islamic credentials of the Ottoman state while suppressing political participation and dissent. These chapters also trace the mounting social tensions and resentments that beset diverse peoples of the Ottoman Empire during an era of territorial losses and incipient nationalisms. The Epilogue concludes by considering methods of approaching this history and by mulling over the relevance of this history for how we will make sense of things that have happened – in other words, for the future of the past.

Conclusion

In 1876, the Ottoman Empire had a population that was estimated to be 25 percent Christian, 1 percent Jewish, and 74 percent Muslim.65 Today, outside Israel, Jewish populations in Middle Eastern countries are minute to nonexistent, while Christian communities have greatly diminished, largely as a result of migration for economic and political reasons, and as an outgrowth of wars.

In 2008, according to the Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs in London, one-third of the world’s 1.5 billion Muslims were living as minorities in predominantly non-Muslim countries.66 Hindu-majority India claimed the largest Muslim minority,67 although by 2015, Muslim populations in Europe and North America were growing quickly, as a result of economically and politically motivated migrations and higher birthrates relative to non-Muslims. In places like Amsterdam and New York, Muslims were striving to affirm their religious identities and to find their social footing while sharing spaces and cultures with non-Muslims, crossing paths in places like grocery stores, and building friendships in schools. Muslims in diasporic communities were also welcoming new members into their communities through conversion, or were themselves exiting Islam for other religions.68 In short, people of Muslim origins were contributing to the cultural richness and sophistication of the countries that had received them – much as Christians, Jews, and others once enhanced the cosmopolitanism of the societies where Islamic states prevailed.69

Amidst these changing currents, does the history of intercommunal relations in the Middle East have lessons to impart? Certainly this history can tell us something about where “we” (meaning denizens of the world, and inheritors of the past) have been, and how we have arrived where we are now. As this book will show, the history, in a nutshell, went something like this: Beginning in the seventh century, when the religion of Islam and the Muslim empire were born, Muslim-ruled states developed a system for integrating Christians and Jews. That is, they made a pact called the dhimma, so that in return for accepting Muslim rule and respecting Islam’s cultural supremacy, Christians and Jews could continue to worship as they had done and pursue livelihoods without interference from Muslim authorities. This system worked reasonably well as a model of Islamic imperial rule for many centuries. Yet this system proved untenable in the modern period, as ideas about nationalism and national participation, new cultures of mass consumption, and changing distributions of education and wealth led some Christians, Jews, and Muslims to question old forms of imperial rule as well as traditional social hierarchies. Indeed, the dhimma system in the Middle East may have once worked well as a means of managing religious diversity, but it cannot suffice today when ideals of nationalism, citizenship, and national belonging are globally pervasive, and when nation-states, not empires, are normative units of political culture. People, worldwide, want to be told they are equal. In today’s world, any state that upholds one religion, sect, or ethnic group in the presence of others, and assumes hierarchies of citizenship accordingly, is bound to chafe the subordinated.

“Redescribing a world,” Salman Rushdie suggested, “is the necessary first step towards changing it.” Does this mean that history gives room for maneuver? If we look back without flinching, then the answer may be yes. Working from this assumption, this book describes the social circumstances that both drew Middle Eastern peoples together and pushed them apart within the fray of everyday life.