Goemai is an Afroasiatic (Chadic, West Chadic A, Angas-Goemai group) language spoken in Central Nigeria. The name Goemai [ɡ

![]() m

m

![]() i] is used by the speakers themselves to refer to both their language and their ethnic group. To outsiders, they are better known under the name Ankwe – a name that is also commonly found in the older linguistic, anthropological and historical literature. The Goemai live as farmers, fishermen and hunters in villages throughout the lowland savannah region south of the Jos Plateau and north of the Benue River, an area that is known geographically as the Great Muri Plains. The economy is based on agriculture (yam, millet, guineacorn, groundnut, beniseed) and is supplemented with fishing and hunting. Politically, the area belongs to Plateau State, and more specifically to the Local Government Areas Shendam and Qua’an Pan. Smaller Goemai-speaking communities are found in surrounding Local Government Areas as well as in Jos, the capital of Plateau State.

i] is used by the speakers themselves to refer to both their language and their ethnic group. To outsiders, they are better known under the name Ankwe – a name that is also commonly found in the older linguistic, anthropological and historical literature. The Goemai live as farmers, fishermen and hunters in villages throughout the lowland savannah region south of the Jos Plateau and north of the Benue River, an area that is known geographically as the Great Muri Plains. The economy is based on agriculture (yam, millet, guineacorn, groundnut, beniseed) and is supplemented with fishing and hunting. Politically, the area belongs to Plateau State, and more specifically to the Local Government Areas Shendam and Qua’an Pan. Smaller Goemai-speaking communities are found in surrounding Local Government Areas as well as in Jos, the capital of Plateau State.

Goemai is a major indigenous language in Plateau State, but its use and distribution is decreasing rapidly in favour of Hausa. Hausa is the language used in administrative, religious and educational settings as well as in everyday contact with non-Goemai neighbours. Among the younger generation, Hausa has become the language of everyday communication even in intra-group contexts. Moreover, children in all larger settlements grow up with Hausa as their first, and often only, language. In 1995, there were an estimated 200,000 ethnic Goemai (Lewis, Simons & Fenning Reference Lewis, Simons and Fennig2013), but the number of actual speakers is assumed to be smallerː while members of the older generation are still fluent speakers, the variety spoken by middle-aged speakers already shows considerable influence from Hausa; and those among the younger generation who still speak Goemai resort to extensive code-mixing and code-switching strategies. In addition to Hausa, many Goemai speakers also speak other local languages, and some also speak English, the national language of Nigeria, which is used in limited official domains (e.g. in education and some mass media).

The speaker in this Illustration is Mr Louis Longpuan, an elderly speaker who was recorded over a period of several years (between 1998 and 2005, when he was between 63 and 70 years of age approximately). He is a speaker of the K’wo dialect (other dialects are Dorok, Duut and East Ankwe), and a resident of the city of Jos. The data for this Illustration were recorded by the second author, and phonetic analysis was carried out by the first author. All Goemai words that appear in this article are listed, annotated, in the appendix.

The starting point for this illustration is the phonological analysis presented in the second author's grammar of Goemai (Hellwig Reference Hellwig2011ː 17–66), and the interested reader is referred to this grammar for details. These details include the justification of all posited phonemes by means of minimal pairs, the description of all allophones, as well as detailed discussions about the possible diachronic origins of innovated phonemes. From the perspective of West Chadic, Goemai exhibits a number of typical phonological featuresː the existence of implosive consonants, a phonemic contrast in vowel length, and two level tones. Unexpected features include an innovated contrast between aspirated and non-aspirated obstruents, a lack of ejective consonants, the extensive modification of consonants through secondary articulation (palatalization, labialization, prenasalization), a large vowel inventory that arises through the innovation of several long vowel phonemes, the existence of predominantly monosyllabic words with a preferred syllable structure of CV(V)C, as well as a severely restricted consonant inventory in word- and syllable-final position. With the exception of the first point, all unexpected features are shared by related and non-related neighbouring languages, and possibly constitute areal features of the Jos Plateau sprachbund as a whole (see also Wolff & Gerhardt Reference Wolff and Gerhardt1977, Pawlak Reference Pawlak2002).Footnote 1

Consonants

The consonant inventory is characterized by a four-way laryngeal contrast in oral stops, and a three-way laryngeal contrast in fricatives. Both oral stops and fricatives occur as voiced, voiceless and aspirated variants, and the bilabial and alveolar places of articulation also include implosives. The full consonant inventory occurs in syllable- and word-initial position only, and this section therefore only exemplifies consonants in this position (see the discussion below on syllable structures for details).

Although Hellwig (Reference Hellwig2011) considers the contrast between the two types of voiceless oral stops to be one of aspiration, other students of Goemai have analysed the contrast differently. Wolff (Reference Wolff1959), for example, labels the contrast as fortis vs. lenis, and Hoffman (Reference Hoffman1975) labels it as glottalized vs. non-glottalized. Hellwig notes that a glottalized variant is possible for the unaspirated velar /k/ [k’]. In the present speaker's data, the voiceless aspirated stops /pʰ tʰ kʰ/ show mean burst/aspiration values of between 66 ms and 87 ms, whereas the unaspirated /p t k/ show mean burst/aspiration values of 21–35 ms (based on 441 non-final voiceless stop tokens). This provides evidence that aspiration plays a key role in the contrast between the two sets of voiceless stops, at least for this speaker.

Goemai is also described as having aspirated and unaspirated fricatives. Hellwig describes the aspiration contrast in fricatives as being mainly cued by duration (with aspirated fricatives having a longer noise portion than unaspirated fricatives) and by truncated formant transitions (for aspirated fricatives, formant values at vowel onset are closer to vowel target values). However, examination of 198 non-final voiceless fricative tokens from the present speaker suggests that these cues are not reliable in all instances. Although mean consonant duration values were greater for aspirated /fʰ ʃʰ/ than for unaspirated /f ʃ/, this was not the case for /sʰ/ vs. /s/. And only /ʃʰ/ vs. /ʃ/ appeared to show a difference in F2 onset values, with the unaspirated /ʃ/ having a higher F2 onset value than aspirated /ʃʰ/ (i.e. further removed from the vowel target value). Examination of FFT spectra at both fricative midpoint and at around the fricative/vowel boundary likewise failed to show consistent differences between aspirated and unaspirated fricatives (it was hypothesized that a more breathy quality may persist into the vowel following the release of aspirated fricatives). It is therefore clear that the contrast between aspirated and unaspirated fricatives requires further instrumental phonetic investigation.

In addition to voiceless aspirated and non-aspirated obstruents, Goemai has voiced obstruents and implosives. Hellwig describes the implosives as being similar to the creaky voiced implosives of Hausa and other Chadic languages (i.e. characterized by a few irregular periods of voicing during the closure and an irregularity in the first few voicing periods at the onset of the vowel). However, this was not obvious in all tokens of the present speaker's data. Instead, the contrast between regularly voiced stops and implosives seemed to be largely cued by the intensity of voicing and by a much higher F1 value at stop release. Figure 1a shows that the spectral peak below 1 kHz (possibly reflecting a combined f0-F1 spectral prominence) is much greater in intensity following the implosive stops than following the regular voiced stops (note that there is no velar implosive). Relatedly, Figure 1b shows that the F1 onset value for implosives is much lower than for regular voiced stops (this observation applies across high, mid and low vowel contexts for this speaker's data, with the exception of the regular voiced bilabial /b/ in the low vowel context). As noted by Ladefoged (Reference Ladefoged1964), the lower F1 value following implosives is due to the expansion of the pharyngeal cavity, which results when the larynx is lowered to produce an implosive stop. It is therefore noteworthy that in the present speaker's data, the regular voiced /b/ also has a low F1 value when the following vowel is low, since the entire tongue is already low at the moment of stop release, presumably with a large pharyngeal cavity as well as a large oral cavity already in place.

Figure 1 (a) Averaged FFT spectra of voiced and implosive stops, taken at stop release, and based on 431 non-final tokens (bilabial and alveolar only). (b) Averaged, time-normalized formant trajectories for the same voiced and implosive stop tokens. In both figures, data are collapsed across vowel contexts. Capital letters represent implosives, and lower-case letters represent regular voiced stops.

Alveo-palatal fricatives developed diachronically from palatalized alveolar and velar obstruents in some environments. The secondary feature of palatalization is often still audible in the case of the non-aspirated voiceless alveo-palatal fricative (e.g. /ʃ

![]() ŋ/ ‘hunt’ in the present dataset), occurring in free variation with the non-palatalized form. Synchronically, however, alveo-palatal fricatives do not allow for the secondary feature of labialization (see below). In addition, the voiced alveo-palatal fricative may be alternatively realized as a voiced alveo-palatal stop (also in free variation).

ŋ/ ‘hunt’ in the present dataset), occurring in free variation with the non-palatalized form. Synchronically, however, alveo-palatal fricatives do not allow for the secondary feature of labialization (see below). In addition, the voiced alveo-palatal fricative may be alternatively realized as a voiced alveo-palatal stop (also in free variation).

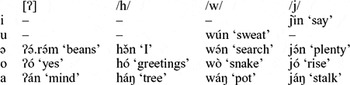

Goemai also has a glottal stop [ʔ] (not included in the chart above) and a glottal fricative/approximant /h/. Their phonemic status is not entirely clear. In Goemai, all vowel-initial syllables are phonetically preceded by a glottal stop. As such, the occurrence of the glottal stop is predictable, and it is (tentatively) not analyzed as a phoneme. However, the analysis is complicated by the observation that there are no close front or back vowels in vowel-initial syllables. The glides, by contrast, show a complementary distribution in precisely this environmentː /j/ precedes /i/, and /w/ precedes /u/. This distribution suggests that at least some glides are phonetically-conditioned variants, preceding close vowels in vowel-initial syllables. In other environments, however, glides do contrast, and are thus considered phonemes. A further complication is introduced by the glottal /h/ː it is possible that it also plays a role in the realization of vowel-initial syllables, as it never precedes close front or back vowels. The distribution of [ʔ], /h/, /w/ and /j/ is as followsː

Distribution of glottals and semivowels

Finally, Goemai has nasals and liquids. In the case of nasals, Goemai contrasts three places of articulation. While the labial and alveolar nasals are frequently found in initial position, the velar nasal occurs only very rarely in this environment. In the case of liquids, Goemai contrasts a lateral and a trill (note that the plain lateral is occasionally realized as a lateral fricative).

It should be noted that Goemai does not have any geminated consonants occurring in native Goemai words.

Below is a list of (near-)minimal pairs for the obstruent, nasal and liquid consonants, respectively, of Goemai.

Secondary articulation

Most morpheme-initial consonants can occur with a secondary articulation of labialization, palatalization or pre-nasalization. Note that these are local phenomena that modify the consonant only. They are thus very different from the palatalization and labialization prosodies of Central Chadic languages that affect the realization of all vowels in the word. Labialization and palatalization are mutually exclusive, but pre-nasalization can co-occur with either of them. However, labialization and palatalization cannot occur before close vowels. Labialization is realized as [ʉ] following labial and glottal consonants, and as [w] elsewhere.

Vowels

Goemai has a large vowel inventory of four short and seven long vowel phonemes. The full inventory only occurs in syllables of the type CV(V)Cː only a restricted set of vowels occurs in syllables of the type V(V)C (see the discussion on the glottal stop above), and the distinction between long and short vowels is neutralized in syllables of the type CV.

The short vowels contrast with long vowels in identical environmentsː /a/ vs. /aː/, /ə/ vs. /eː/ (note the accompanying difference in vowel quality), /u/ vs. /uː/, and /i/ vs. /iː/ (note that this last contrast is attested in a handful of near-minimal pairs only). The three long vowels /ʉː/, /oː/ and /ɔː/ do not contrast phonemically with their short counterpartsː they have short allophones in environments where Goemai does not allow for long vowels (especially when preceding a velar consonant), but are otherwise long. They might have originated through the loss of intervocalic consonantsː cognate forms in other Angas-Goemai group languages almost always contain sequences of ‑VCV-, compare e.g. Goemai [s

![]() ːm] with Mwaghavul [soɣom] ‘horn’ (Hoffman Reference Hoffman1975). Note also that vowel length interacts with labialization and palatalizationː when following such a modified consonant, short vowels can alternatively be realized long, e.g. /nʲák/ ‘breathe’ is realized [nʲáːk] in the accompanying recording.

ːm] with Mwaghavul [soɣom] ‘horn’ (Hoffman Reference Hoffman1975). Note also that vowel length interacts with labialization and palatalizationː when following such a modified consonant, short vowels can alternatively be realized long, e.g. /nʲák/ ‘breathe’ is realized [nʲáːk] in the accompanying recording.

In addition, the distribution of close vowels is very restricted for diachronic reasons. The close front vowels /i/ and /iː/ cannot follow the alveolar fricatives (/sʰ/, /s/ and /z/) and the velar stops (/kʰ/, /k/ and /g/) because these sound combinations gave rise to the present-day alveo-palatal fricatives (/ʃʰ/, /ʃ/ and /ʒ/). Furthermore, no close vowel can occur in syllables of the type V(V)(C) or be preceded by /h/. The reason is again a diachronic reason. Goemai did not allow for vowel-initial syllables on a phonetic levelː non-close vowels were preceded by a glottal consonant in this environment, while close vowels were preceded by their corresponding glide – i.e. the occurrence of the glides was predictable (/i/ and /iː/ were invariably realized as [ji] and [jiː], and /u/ and /uː/ as [wu] and [wuː] in this environment), and the glides thus did not constitute phonemes. In the present-day language, however, there are reasons to analyze the previously phonetically conditioned variants [h], [w] and [j] (albeit not [ʔ]) as phonemes (see above for their distribution), and to posit the existence of vowel-initial syllables on a phonemic level. This process of phonemicization has had repercussions for the synchronic distribution of the close vowels: /i/ and /iː/ are preceded by the synchronic phoneme /j/, while /u/ and /uː/ are preceded by the synchronic phoneme /w/ in all words that were diachronically vowel-initial. Or stated negatively, it is reflected in the synchronic restriction that /i/ and /iː/ cannot be preceded by /w/, and /u/ and /uː/ cannot be preceded by /j/, and neither of them can be preceded by a glottal or occur in a vowel-initial syllable. Finally, no close vowels are synchronically attested following labialized or palatalized consonants as such sound combinations have been re-analyzed as long vowels.

There is a tendency for speakers of all dialects to realize short [a] in loanwords as [ə], e.g. Hausa /tʰáɓàː/ ‘have ever/never done’ is often realized as /tʰ

![]() ɓà/.

ɓà/.

Vowel length and vowel quality furthermore interact with prosodic prominence in that a prosodically prominent (i.e. ‘stressed’) open syllable – independent of its position within a word – is realized phonetically long and is never realized as schwa. Instead, schwa is realized as [ɔː] in this environment.

Goemai also has a limited set of diphthongs, which are not lexically frequent. These are [au], [ou], [ai], [ei] and [oi].Footnote 2 It can be seen that the second vowel target can only be [u] or [i]; unlike long vowels, these diphthongs cannot occur with a consonant coda. Hellwig (Reference Hellwig2011ː 39–40) analyzes these diphthongs phonologically as sequences of vowels plus glides.

In addition, the sequences [

![]() ə] and [

ə] and [

![]() a] exist as variant realizations of the secondary feature of labialization following a labial consonant e.g. /mʉ

a] exist as variant realizations of the secondary feature of labialization following a labial consonant e.g. /mʉ

![]() p/ muěp or /mʉàːn/ muààn in ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ passage – more accurately transcribed [m

p/ muěp or /mʉàːn/ muààn in ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ passage – more accurately transcribed [m

![]()

![]() p] and [m

p] and [m

![]()

![]() ːn].

ːn].

Figure 2a shows the long and short vowel phonemes of Goemai based on the speaker in this Illustration (all tokens taken from non-final position). It can be seen that the corner vowels /i, a, u/ are more peripheral when long, and that the schwa vowel is truly central. Moreover, it can be seen that the mid back vowels /oː ɔː/ are relatively close together in the vowel space and show a good deal of overlap. Figure 2b shows the length-neutralized final vowels, based on 196 tokens.

Figure 2 (a) Long and short vowel phonemes of Goemai, based on 1349 medial tokens. (b) Neutralized final vowels, based on 196 tokens. The speaker is Mr Louis Longpuan. Formants were sampled at the token midpoint using the Pitch and Formant tool in Emu 2.3 (default window setting modified to Hamming). Note that @ = /ə/, uː = /ʉː/ and oː = /ɔː/.

Vowel examplesFootnote 3

Medial position (short vowel)

Medial position (long vowel)

Final position Footnote 4

Diphthong examples

Tones

Goemai is a tonal language, and all lexical items and almost all affixes and clitics have an inherent tonal pattern. There are two level tones (high H and low L), which can be combined on one syllable to give a HL pattern. Such HL patterns are predominantly found on long vowels. An underlying LH pattern is posited for a small number of items from different word classes (especially subject pronouns, but also including some nouns, verbs and TAM ( = Tense Aspect Mood) markers). Such LH patterns never surface on a single syllable – instead, they are distributed as follows: the L tone surfaces on all syllables of the first word, and the H tone on the first syllable of the following word. Compare the different tonal realizations below of the two cognate object constructions /kʷál

kʷál/ and /kʰùt kʰùt/ (both meaning ‘talk a talk’). In the first set, they are preceded by the cliticized pronoun /m

![]() = / ‘1pl’ː the L tone of the pronoun is realized on the first word (pronoun plus verb), and the H tone on the second (the cognate object), thus resulting in identical patterns. In the second set, they are preceded by a word comprised of the proclitic /h

= / ‘1pl’ː the L tone of the pronoun is realized on the first word (pronoun plus verb), and the H tone on the second (the cognate object), thus resulting in identical patterns. In the second set, they are preceded by a word comprised of the proclitic /h

![]() n = / ‘1sg’ and the TAM particle /t

n = / ‘1sg’ and the TAM particle /t

![]() ŋ/ ‘irrealis’. Again, the L tone of the pronoun is realized on the first word (the phonetically reduced pronoun plus the TAM particle), and the H tone on the second word (the verb); from the third word onwards (the cognate object in this case), the underlying tones surface again. In environments where a LH pattern cannot be realized over two words, it is simplified to a level high tone. Phonetically, downstepped H tones are also present.

ŋ/ ‘irrealis’. Again, the L tone of the pronoun is realized on the first word (the phonetically reduced pronoun plus the TAM particle), and the H tone on the second word (the verb); from the third word onwards (the cognate object in this case), the underlying tones surface again. In environments where a LH pattern cannot be realized over two words, it is simplified to a level high tone. Phonetically, downstepped H tones are also present.

Example realization of LH patternsFootnote 5

Tone is clearly a distinctive phonological property of the languages, but it has to be kept in mind that its functional load is restrictedː most minimal pairs belong to different parts of speech; grammatical tone often neutralizes lexical tone; and grammatical constructions are primarily marked by segmental morphemes rather than tone.

Tone examples

Although tone serves to distinguish lexical items, lexical tone is not necessarily realized on the lexical item itself. This is largely due to a high-tone spreading rule originating in some subject pronouns and nouns (the LH patterns mentioned above). It should be noted that high-tone spreading to the right is the most common type of spreading in Goemai, but there are also a few high-frequency lexical items that trigger high-tone spreading to the left. In addition, there are a number of intonational processes that affect the realization of tones. The two most prominent such processes are: (i) downdrift (where a L tone triggers a downstep in a following H tone), and (ii) a phrase-final low tone (which causes H tones to be realized as falling, and L tones as extra-low).

Syllable structure

The syllable structure template is (C)V(V)(C), whereby the first consonant can be modified by the secondary features of labialization, palatalization or prenasalization. Goemai has a small number of vowel-initial syllables, which are preceded phonetically by a glottal stop. As discussed above, the phonemic status of the glottal stop is questionable, and it is tentatively not analyzed as a phoneme.

Goemai can be characterized as a predominantly isolating languageː morphemes tend to be monosyllabic, and words tend to be monomorphemic. The vast majority of words thus have the structures ( n )C(ʷ/ʲ)V, ( n )C(ʷ/ʲ)VC and ( n )CVVC. Polysyllabic words are rare and arise through one of the following processesː the addition of a prefix or proclitic of the shape N or CV to a lexical item of any shape (note that there are only few such affixes and clitics), the partial reduplication of lexical items of any shape (adding an initial CV syllable), a small number of pluractional verbs and plural nouns (of the shape CV.CVC) as well as a small number of lexicalized nominal compounds (of all shapes). In all cases, a number of phonetic processes are attestedː simplification of medial consonant clusters, assimilation of nasals, lenition of intervocalic consonants and reduplicated implosives, and changes in the vowel length and vowel quality of non-prominent syllables. These processes are responsible for the majority of polysyllabic words to be of the shape CV.CV(V)(C), with schwa being by far the most common vowel in the initial CV syllable.

The full consonant inventory occurs in initial position, and only a small subset is allowed in final position. The laryngeal contrast between obstruents is neutralized in final position. Note also that only one fricative (/s/) is attested in this position at all. As a result, the only consonants which appear in syllable-final position are /p t k s m n ŋ l r w j/. Following /u/, the labial stop /p/ is alternatively realized as the velar stop [k].

Transcription

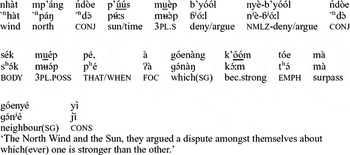

This version of ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ was translated and recorded by Louis Longpuan in Jos (Nigeria) on 26 October 2005. In all three renditions of the story, the text is broken down into numbered sentences (as determined by Louis Longpuan). Commas represent pauses in the recorded version and ‘(…)’ represents omitted material due to a false start.

Goemai orthography

-

(1) nhàt mp’áng ńdòe p’úús muèp b’yóól nyèb’yóól ńdòe sék muép pé, à góenàng k’óóm tóe mà góenyé yì. (2) ńdòe gòemuààn muààn, dóe p’ét k’á muép, gòng sék múk góe lé gòegòng k’út. (3) muèp yín, gùrùm gòepé lá b’óót gòe sà gòemuààn muààn, ńnòehòe, lwén twén múk, hók, bá nní, à ní tóe, à gòek’óóm má yì. (4) nhàt mp’áng sù sék gòezèm k’yák jí. (5) bòet’óng sù múk hók, gòemuààn muààn b’ép t’óng, gòng súún kúút, góe lé gòeb’áán. (6) nyáng má nhàt mp’áng nní, sái, kwán, nyèb’yóól hók nk’wà. (7) p’úús, p’ét kúút b’áán làp pè díp. (8) gòemuààn muààn, wép (…) lé jí, gòeb’áán kúút, kwán. (9) sái nhàt mp’áng yìn, hái, yìn à p’úús tóe, à gòek’óóm má yì.

Phonemic transcription

-

(1) ˋn hàt ˋn páŋ ˊn d

p

p

ːs

mʉ

ːs

mʉ

p ɓʲóːl

nʲèɓʲóːl ˊn

d

p ɓʲóːl

nʲèɓʲóːl ˊn

d

sʰ

sʰ

k

mʉ

k

mʉ

p

pʰé, ʔà ɡ

p

pʰé, ʔà ɡ

nàŋ k

nàŋ k

ːm

tʰ

ːm

tʰ

mà ɡ

mà ɡ

nʲé jì. (2) ˊn

d

nʲé jì. (2) ˊn

d

ɡ

ɡ

mʉàːn

mʉàːn, d

mʉàːn

mʉàːn, d

p

p

t

ká

mʉ

t

ká

mʉ

p, ɡ

p, ɡ

ŋ sʰ

ŋ sʰ

k

múk ɡ

k

múk ɡ

lé ɡ

lé ɡ

ɡ

ɡ

ŋ kút. (3) mʉ

ŋ kút. (3) mʉ

p

jín, ɡùrùm ɡ

p

jín, ɡùrùm ɡ

pʰé lá ɓóːt ɡ

pʰé lá ɓóːt ɡ

sʰà ɡ

sʰà ɡ

mʉàːn

mʉàːn, ˊn

n

mʉàːn

mʉàːn, ˊn

n

h

h

, lʷ

, lʷ

n

tʰʷ

n

tʰʷ

n

múk, h

n

múk, h

k, bá ˋn

ní, ʔà

ní tʰ

k, bá ˋn

ní, ʔà

ní tʰ

, ʔà ɡ

, ʔà ɡ

k

k

ːm

má

jì. (4) ˋn

hàt ˋn

páŋ sʰù sʰ

ːm

má

jì. (4) ˋn

hàt ˋn

páŋ sʰù sʰ

k ɡ

k ɡ

z

z

m

kʲák ʒí. (5) b

m

kʲák ʒí. (5) b

t

t

ŋ sʰù múk

h

ŋ sʰù múk

h

k, ɡ

k, ɡ

mʉàːn

mʉàːn ɓ

mʉàːn

mʉàːn ɓ

p

t

p

t

ŋ, ɡ

ŋ, ɡ

ŋ sʰ

ŋ sʰ

ːn

kʰ

ːn

kʰ

ːt, ɡ

ːt, ɡ

lé ɡ

lé ɡ

ɓáːn. (6) nʲáŋ má ˋn

hàt ˋn

páŋ ˋn

ní, sʰáj, kʰʷán, nʲèɓʲóːl

h

ɓáːn. (6) nʲáŋ má ˋn

hàt ˋn

páŋ ˋn

ní, sʰáj, kʰʷán, nʲèɓʲóːl

h

k ˋn

kʷà. (7) p

k ˋn

kʷà. (7) p

ːs, p

ːs, p

t

kʰ

t

kʰ

ːt ɓáːn

làp

pʰè díp. (8) ɡ

ːt ɓáːn

làp

pʰè díp. (8) ɡ

mʉàːn

mʉàːn, w

mʉàːn

mʉàːn, w

p (…) lé ʒí, ɡ

p (…) lé ʒí, ɡ

ɓáːn

kʰ

ɓáːn

kʰ

ːt, kʰʷán. (9) sʰáj ˋn

hàt ˋn

páŋ jìn, háj, jìn ʔà

p

ːt, kʰʷán. (9) sʰáj ˋn

hàt ˋn

páŋ jìn, háj, jìn ʔà

p

ːs

tʰ

ːs

tʰ

, ʔà ɡ

, ʔà ɡ

k

k

ːm

má

jì.

ːm

má

jì.

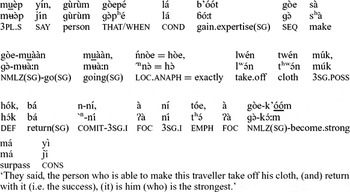

Interlinearized version

This version contains the following four linesː

-

• Goemai orthography (using hyphens to indicate morpheme breaks)

-

• Phonemic transcription

-

• English gloss, making use of the following grammatical abbreviationsː comit = comitative; cond = conditional; conj = conjunction; cons = consequence clause; def = definite article; emph = emphasis; foc = focus; i = independent pronoun; irr = irrealis; loc.anaph = locative anaphor; log.sp = speaker logophoric (co-reference with the speaker); m = masculine; nmlz = nominalizer; pl = plural; poss = possessive; s = subject pronoun; seq = sequential; sg = singular; spec = specific article

-

• Reverse literal translation of the Goemai version back into English

-

(1)

-

(2)

-

(3)

-

(4)

-

(5)

-

(6)

-

(7)

-

(8)

-

(9)

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to Mr Louis Longpuan, the speaker in this study, and to Mr Shalyen Mbai Nwang. We would also like to thank Josh Butler, Daniela Diedrich and Nick Gurling for their work labelling the phonetic data as part of an Acoustic Phonetics class project, and two anonymous reviewers for comments on an earlier version. This research was funded by the Australian Research Council, the Endangered Languages Documentation Program, and the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics.

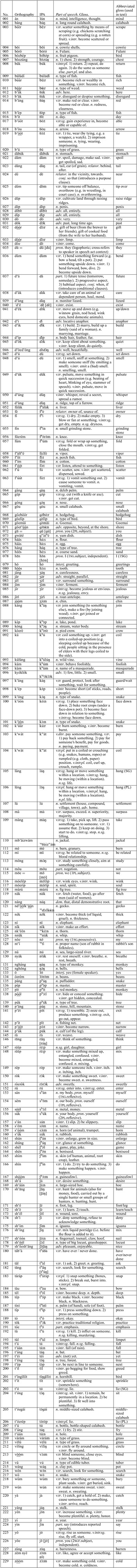

Appendix. Wordlist

This wordlist contains all Goemai words that appear in this article. The lexical entries are structured as follows: (i) sequential index number (linking the entry to the accompanying recording), (ii) lexeme (in Goemai orthography), (iii) lexeme (in IPA), (iv) part of speech, and English gloss, and (v) abbreviated gloss (as used in the main body of the article and in the accompanying recordings). The entries are listed in alphabetical order, following a modified version of the Goemai orthography developed in Sirlinger (Reference Sirlinger1937): a b b’ d d’ e f f’ g h i j k k’ l m n ng o o oe p p’ r s s’ sh sh’ t t’ u u v w y z.

The following abbreviations are used in the appendix: adv = adverb; conj = conjunction; dem = demonstrative; interj = interjection; n = noun; part = particle; pl = plural; pron = pronoun; relator = relator noun; sg = singular; v.ditr = verb (ditransitive); v.intr = verb (intransitive); v.tr = verb (transitive).